9,59 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Allison & Busby

- Kategorie: Krimi

- Serie: Mary Russell & Sherlock Holmes

- Sprache: Englisch

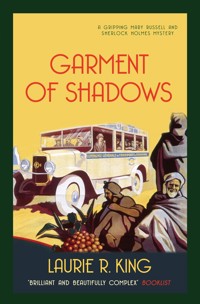

In a strange room in Morocco, Mary Russell is trying to solve a pressing mystery: Who am I? She has awakened with shadows in her mind, blood on her hands, and soldiers pounding on the door. Out in the hive-like streets, she discovers herself strangely adept in the skills of the underworld, escaping through alleys and rooftops, picking pockets and locks. She is clothed like a man, and armed only with her wits and a scrap of paper containing a mysterious Arabic phrase. Meanwhile, Holmes is pulled into the growing war between France, Spain, and the Rif Revolt led by Emir Abd el-Krim-who may be a Robin Hood or a power mad tribesman. The shadows of war are drawing over the ancient city of Fez, and Holmes badly wants the wisdom and courage of his wife, whom he's learned has gone missing. As Holmes searches for her, and Russell searches for herself, each tries to crack deadly parallel puzzles before it's too late for them, for Africa, and for the peace of Europe.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 461

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2012

Ähnliche

GARMENT OF SHADOWS

LAURIE R. KING

This book is dedicated to those who reach across boundaries with a hand of welcome.

‘Let us learn their ways, just as they are learning ours.’

– HUBERT LYAUTEY

Contents

TITLE PAGE

DEDICATION

AUTHOR’S PREFACE

EPIGRAPH

MAP

PREFACE

CHAPTER ONE

CHAPTER TWO

CHAPTER THREE

CHAPTER FOUR

CHAPTER FIVE

CHAPTER SIX

CHAPTER SEVEN

CHAPTER EIGHT

CHAPTER NINE

CHAPTER TEN

CHAPTER ELEVEN

CHAPTER TWELVE

CHAPTER THIRTEEN

CHAPTER FOURTEEN

CHAPTER FIFTEEN

CHAPTER SIXTEEN

CHAPTER SEVENTEEN

CHAPTER EIGHTEEN

CHAPTER NINETEEN

CHAPTER TWENTY

CHAPTER TWENTY-ONE

CHAPTER TWENTY-TWO

CHAPTER TWENTY-THREE

CHAPTER TWENTY-FOUR

CHAPTER TWENTY-FIVE

CHAPTER TWENTY-SIX

CHAPTER TWENTY-SEVEN

CHAPTER TWENTY-EIGHT

CHAPTER TWENTY-NINE

CHAPTER THIRTY

AUTHOR’S AFTERWORD

EDITOR’S NOTE

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS AND NOTES

GLOSSARY

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

BY LAURIE R. KING

COPYRIGHT

AUTHOR’S PREFACE

IT SHOULD BE NOTED that sections of this volume of my memoirs depict acts and thoughts of people that took place in my absence. I chose the God-like point of view because I thought it less distracting for a reader. In fact, those sections reflect testimonies pieced together out of disjointed segments and off-hand remarks given over the course of weeks, and even years.

If this style of narrating my memoir causes readers to interpret the following as fiction, so be it. It would not be the first time.

– MARY RUSSELL HOLMES

I have attached a glossary of unfamiliar terms at the end.

– MRH

… the breath of Chitane Blows the sands in smoky whirls And blinds my steed. And I, blinded as I ride, Long for the night to come, The night with its garment of shadows And eyes of stars.

– EBN EL ROUMI

PREFACE

THE BIG MAN HAD the brains of a tortoise, but even he was beginning to look alarmed.

Sherlock Holmes drew a calming breath. Then another.

It had seemed such a simple arrangement: If Mary Russell chose to submit to the whimsy of Fflytte Films as it finished its current moving picture, that was fine and good, but there was no cause for her husband to be tied down by her eccentricities – not with an entirely new country at his feet. He’d never been to Morocco. After some complex marital negotiations, he promised to return, at an agreed-to time and place, which was here and today.

Except she was not there.

He started again. ‘So she left her tent that night. After dark.’

‘Oui, Monsieur.’

‘And was still gone the next morning.’

‘Oui, Monsieur.’

‘She spoke to no one, merely left a brief note to say that she was going to Fez.’

The man nodded.

‘The filming ended. The rest of Fflytte’s crew came back here. No one thought this odd. And all you have to say is that my wife was last seen walking into the desert in the company of a child. Three days ago.’

Morocco might be a small country, but it was plenty big enough to swallow one young woman.

Russell, he thought, what the devil are you up to?

CHAPTER ONE

IWAS IN BED.A bed, at any rate.

I had been flattened by a steam-roller, trampled under a stampede of bison. Beaten by a determined thug. I ached, head to toe, fingers and skin. Mostly head.

My skull throbbed, one hot pulse for every beat of my heart. I could see it in the rhythmic dimming of an already shadowy room. I wanted to weep with the pain, but if I had to blow my nose, my skull might split like an overripe melon.

So I lay in the dim room, and watched my heart beat, and ached.

Some time later, it came to me that the angle of the vague patch of brightness across the opposite wall had changed. Some time after that, an explanation slipped out between the pain-pulses: The sun had moved while I slept. A while later, another thought: Time is passing.

And with that, a tendril of urgency unfurled. I could not lie in bed, I had to be somewhere. People were depending on me. The sun would go down: I would be late.

Rolling onto my side was like pushing a motorcar up a hill. Raising myself up from the thin pad made me cry out – nearly black out – from the surge of pressure within my skull. My stomach roiled, my ears rang, the room whirled.

I crouched for a long time on the edge of the bed. Slowly, the pounding receded. My vision cleared, revealing a snug, roughly plastered room; hand-made floor tiles; a tawny herringbone of small bricks; a door of some dark wood, so narrow a big man might angle his shoulders, a hook driven into it, holding a long brown robe; a pair of soft yellow bedroom slippers on the floor – babouches, my mind provided: new leather, my nose told me. The room’s only furniture was a narrow bed with a rough three-legged stool at its head. The stool served as a table, its surface nearly covered with disparate objects: in the centre stood a small oil lamp. To its left, nearest the bed, were arranged a match-box, a tiny ceramic bowl holding half a dozen spent matches, a glass of water, and a pair of wire-rimmed spectacles that appeared to have been trod upon. The other side of the lamp had an even more peculiar collection: a worn pencil stub, a sausage-shaped object tightly wrapped in a handkerchief, some grains of sand, and one pale stone.

I studied the enigmatic display. The little bowl caused a brief memory to stir through the sludge that was my brain: As I slept, the sound of a match scratching into life would wake me; the sharp smell would bite my nostrils; faces would appear and make noises; I would say something apparently sensible; the faces would bend over the light, and with a puff, I would be back in the shadows, alone.

My hand reached out, hesitated over the water, rejected it, and picked up the spectacles instead. I winced as they settled between my ears and the snug head wrap I wore, but the room came into focus.

The matches also came into focus: a cheap, bright label, in French. I picked up the box, slid it open, my nose stung by the smell of sulphur. Four matches. I took one, scraped it into life, held it to the oil lamp. A spot of warmth entered the room.

By its thin light, I looked down at what I wore. Drab homespun trousers and tunic. Bare feet. The clothing was clean, but not my hands. They looked as if someone had tried to wipe away a layer of some dark greasy matter, leaving stains in the deeper creases and under the nails.

I stretched the left one out nearer the lamp. Motion caused the flame to throw dancing shadows across the room. When it had steadied, I frowned at the finger-nails to which I was attached.

Not grease.

Blood.

The light of a candle / the sunshine smell of linen / the slope of ceiling / the soft throat of a young girl asleep / the blood on my hands—

The bolt of memory shocked me to my feet. I swayed, the room roaring in my ears, my eyes fixed on the flat, slope-free ceiling. Don’t look down (blood on my hands) – don’t think about the hand’s memory of the smooth, intimate glide of sharp steel through flesh.

I ventured a step, then another, towards the shuttered window.

To my surprise, the latch flipped beneath my awkward fingers, and when the hinges creaked open, there were no bars. Why had I expected to be a prisoner?

The brilliance was painful, even though the sky was grey with unshed rain. I lifted a hand to shade my eyes, and squinted at the view: a dirty, cobbled lane far too narrow for any motorcar. One could have passed an object between opposing windows – had there been windows. I saw only one, higher even than mine, tiny and tightly shuttered. I could see two entranceways off this diminutive alley: One had been painted with brightly coloured arabesques, long ago, and comprised a small door inside a larger one, as if the carpenter had learned his craft on castles and cathedrals. The door across from it was a single rectangle, black wood heavily studded with rusting iron circles the size of my thumbnail. Around them, grubby whitewash, a fringe of grass on the rooflines, chunks of plaster flaking from walls that bulged and slumped. In one place, wooden braces thirty feet from the ground kept two buildings from collapsing into each other.

The house I was in seemed to be the lane’s terminus; thirty feet away, beneath the slapdash web of braces, the passageway turned to the right and disappeared.

I pushed the shutters wider open, intending to lean out and examine the face of the building below me, then took a step back as the left-hand door came open and a woman emerged. She was swathed head to toe in pale garments, with a straw bag in one hand and a child’s hand in the other. She glanced down the alleyway, her eyes on a place well below me, and I could see her brown, Caucasian features and startling blue eyes. She pulled her scarf up over her face and tugged the child down the lane, vanishing around its bend.

Arabic; French; woman in a robe – djellaba, the internal dictionary supplied, although that did not seem quite right. Those clues combined with the woman’s Berber features suggested that I was in North Africa. Algeria or perhaps Morocco. In a suq.

The knowledge of where was just beyond my grasp, like an elusive name on the tip of one’s tongue. Similarly, how I came to be here. And what had been so urgent it drove me to my feet. Or why I had blood on my hands.

Or, my name.

Who the hell was I?

CHAPTER TWO

SWEAT BROKE OUT ALL over my body, despite the cold of the room. There was a good explanation, for everything. One that I would remember in a minute, once I could think around the pounding in my head. Or …

I turned to consider the narrow door. The shutters hadn’t been locked. Yes, the window was high and the drop to the lane sheer, but perhaps it meant that my situation was not the source of that feeling of urgency. That the water in the glass was not drugged. That the door led to assistance, to information. To friends, even.

My bare feet slapped across the cold tiles. I stopped beside the bed, transferring everything but the lamp, water, and bowl into my pockets, then moved over to the door and put my ear to the crack: nothing. My fingers eased the iron latch up until the tongue came free; the wood shifted towards me. I was not locked in.

The odours that washed over me threatened to turn my stomach over. Frying oil, onions, chicken, a panoply of spices – for some reason, I felt that if I were more experienced with their names, I would be able to identify each individual element of that sensory cloud.

I pushed aside the evidence of my nostrils, concentrating instead on my vision. The scrap of corridor was no more revealing than the view from the window: the same rough herringbone on the floor, cobalt-and-cream tiles halfway up the walls, with crisp whitewashed plaster above; another door; a tidy stack of straw baskets; the suggestion of a house off to the left. I took a step out: To my right, a stone stairway curled upward out of view – to the roof, I felt, although I could not have said why. Then I heard a voice – two voices, so distant, or behind so many doors, that I could not determine the language, much less the words.

But I could hear the tension.

For some reason, I reached around to the back of my waist-band, my fingers anticipating a cold weight nestled against my spine, but there was nothing. After a moment’s consideration, I drew a breath, and stepped out. Nothing happened.

I crept down the hall to the left and took up a position just before the bend, not venturing my head into the open. The voices were clearer now, the rhythms suggestive of Arabic. Cool air moved across my face and the light around the corner was daylight, not lamps, as if the walls of the house had been sliced away. Words trickled into my mind. Dar: a house of two or three storeys built around a ground-level courtyard, open to the sky; halka: its wide central sky-light; riad: a house whose inner courtyard was a garden.

Another brief internal flash: clipped green rectangle / rain-soaked brick walls / figures in academic gowns / the odour of learning—

I was gathering myself for a step towards that light when a harsh sound juddered through the house, coming from below and behind me at the same time. I hurried back into my tiny cell and across the tiles to peer downwards into the narrow lane—

Soldiers!

No mistaking that blue uniform and cap: two armed French soldiers, pounding on the door below.

Aimless urgency blew into open panic: I could not be taken by them, it was essential that I remain free, that I get to—

To where? To whom? But while I might have given a single gendarme the benefit of the doubt, armed soldiers could only be a declaration of war. I snatched the robe from the hook, stepped into the slippers, and made for the curve of steps leading up.

The upper door’s iron latch opened easily. Outside was a terrace roof around an iron-work grid, open to the house below. On one side was strung a bare laundry line; the furniture consisted of six pots of winter-dead herbs and a pair of benches. The rooftop was empty – had I known it would be? – but it smelt of rain, the drips on the clothes-line showing that it had been recent. The air was very cold.

I worked the robe over my head – it was like a sack with a hood, and to my relief smelt only of wool and soap. I picked up the stick supporting the centre of the clothes-line and brought down one slippered foot on its centre, snapping it in two; jamming the sharp end beneath the door would slow pursuit. And the rope itself – that would be useful. I reached for my ankle, but found only skin where my fingers seemed to expect a knife.

Neither knife nor handgun: not friends, then.

I abandoned the line to make a quick circuit of the rooftop, keeping well clear of the open grid, lest someone looking up see me. All around lay a tight jumble of buildings, their rooftops – squared, domed, and crenellated; brick and stone and tile; crisply renovated or crudely patched or on the point of collapse – at a myriad of levels, like the world’s largest set of children’s blocks. The town covered slopes dropping into a valley; higher hills, green with winter rains, lay in the distance. Here and there, tree-tops poked up between the structures, but there was no discernable break for roads, and the buildings were so intertwined that they appeared to be resting atop one another. Certainly they were holding each other upright – I had seen that from the window below. Several green-roofed minarets sticking above the architectural confusion confirmed that I was in North Africa.

As I circled the rooftop, my fingers automatically laid claim to a few small items left by the women-folk whose territory this was – a pocket-mirror with cracked glass, a tiny pot of kohl, a pair of rusting scissors too delicate to part the laundry rope – and automatically thrust them through the djellaba’s side-slits to the pockets beneath.

The circuit ended, I was faced with a decision: The easiest descent was the most exposed; the most surreptitious way might well kill a person with a head as dizzy as mine.

I looked out over the town, where a faint suggestion of emerging sun was bringing an impression of warmth to the grey, tan, and whitewashed shapes. Weeds sprouted on every flat surface, and storks’ nests. Weren’t those supposed to be good luck? I hoped so. The town’s overall texture had an almost tactile satisfaction that reminded me of something. Something I had seen, touched – honeycomb! But not comb neatly bounded by a wooden frame: wild honeycomb, with orderly hexagons filling up the bumps and hollows of rock or tree. My eyes squinted, making the town blur; the aroma of honey seemed to rise up …

Stop: time for decisions, not distractions. I went to the low wall overhanging a neighbour’s house – then ducked down as a door twenty feet away scraped open and two women came out, arguing furiously in a language I did not know. As I vacillated between waiting for this safer route and risking the other, the door behind me rattled.

Without further consideration, I scurried across the rooftop, pushed through a narrow gap, and dropped down to a wall-top eight feet below. My earlier glance had shown me a glimpse of tiled courtyard through the branches of an orange tree, with this foot-thick wall separating it from a derelict garden next door. I settled my yellow babouches onto the weedy bricks, fixed my gaze on the vestigial window-sill twenty feet away, then balanced like a tight-rope walker across the ragged surface to the abandoned building beyond. Fearful of pursuit, I stepped over the gap and inside – and my heart instantly seized my throat: The brick walls bled light like lace-work; the floor was mostly missing. The entire structure seemed to sway with the addition of my weight.

I stood motionless until bits of mortar and wood stopped drifting down. The breath I took then was slow, but fervent.

Moving with extreme caution, I drew the hand-mirror from my inner pocket and, keeping it well away from the light, held it up to reflect the rooftop behind me. The soldiers came into view.

Their backs were to me. I could hear them shouting at the women on the adjoining rooftop, but either they answered no, they hadn’t seen me, or (more likely) they retreated inside at the first sight of strange men. The soldiers then began the same circuit I had made.

Ending up staring right at me.

I held the glass absolutely still, lest a flash of reflection give me away. They seemed … wrong, somehow, although I could not have said why. Clean-shaven, dark-eyed, their uniforms like any others.

But French soldiers did not belong on a rooftop of that shape.

The men were surveying the tiled courtyard. One of them pointed down and said something. His companion turned briskly for the door. The first took another look around the edges, then he, too, left the rooftop.

Shakily, I lowered myself to the floor. The stable tiled island beneath me did not collapse and the wall, appearances to the contrary, seemed stout enough to support my back. Through a hole, I could see a portion of the neighbouring courtyard. In a few minutes, the military caps appeared. I listened to the soldiers berating the confused and frightened owner, whose French was clearly inadequate for the task of self-defence. Eventually, they left. I waited, the looking-glass propped against a hundred-weight of fallen plaster. Half an hour later, motion came again to the rooftop I had so hastily left.

Between the overcast sky and the dullness of the reflection, it was difficult to make out details of the two people who walked across the rooftop. I abandoned the looking-glass to stand, warily, and peer around the splintery boards that had once framed a window. A man and a woman, she in white drapery, he in a sackcloth robe over shirt and trousers, his turban a circle of cloth revealing the crown of his head. They looked around the rooftop, down the edges, into the neighbouring courtyard, appearing less angry than confused. I was tempted to call out to them, to give them a chance – but that sense of urgency had returned, growing ever stronger as I sat trapped in the crumbling building.

And, they had taken my weapons.

I was blind, no doubt about that. But as the blind are forced to rely on their other senses to find their way (a man, in a heavy fog, explaining the phenomenon – but the image was gone before it was there), so would I rely on what senses I had left, to make my decisions.

I did not call out.

Instead, I waited for the pair to leave. It was cold, so it did not take long. When I was alone – so far as I could tell – I stepped through the hole again and onto the wall.

And paused. A sound rose across the city, a prolonged exhortation. It was joined a minute later by another, then a third farther away. The mid-day call to prayer, a chorus of reminders ringing out across the town, muezzins declaring the greatness of God, reminding the citizens that prayer is better than sleep.

I had heard it before, and yet I had not. I knew it, and yet I was a stranger. I could recite the words, yet I was quite sure they were not my own. Its meaning frightened me; its beauty moved me deeply.

And I must stop succumbing to distraction! I pushed away its spell and dropped into the derelict garden on the other side. While the sound of the adhan faded, I picked my way through weeds and assorted rubbish, startling a pair of cats and slicing a hole in my slippers. On the other side of the garden was a shorter wall and a heap of something that might have been unused tiles. I climbed up, and peered over.

Here was another narrow alleyway, with another pair of stout nail-clad doors, to the right and to the left. Unlike the first passageway, this semi-tunnel opened onto a marginally wider, and more populated, near-street (though even that was too narrow for motorcars). A woman in voluminous ash-coloured garments went past the opening. Two chattering children trotted in the other direction, one of them balancing on his head a tray bigger than he was, carrying loaves of unbaked bread. The children were followed by a donkey with a long wooden bench of fresh-cut cedar strapped to his back, a lad with a switch moving him along. I gathered the hem of my djellaba, scrambled over the wall, and dropped to the damp, slick stones.

My skull seemed to be resigning itself to the abuse; I only needed to lean against the wall for a minute or so before the pounding and spinning receded, and I no longer had to fight back the urge to cry out. When I felt steady, I tugged the robe’s hood over my head and walked down the dark passageway towards the street.

For some reason, I expected to find the narrow streets bustling with activity, but the human beehive was all but deserted. Shops were padlocked. Few donkeys pressed through with their burdens. One of the lanes was so still, I could hear the sound of a buried stream through the paving stones. As I moved into the city, I began to wonder if some awful pestilence had struck my fellows as well. Was the entire populace hiding behind its shutters, infected with my same mental distress, terrified of venturing into the light? Were it not for the unconcerned pace of the occasional shrouded woman who went past and the cries of a group of boys playing in a side-street, I might have begun pounding on doors to find out.

But those residents I passed were clearly untroubled. And the air did not smell of death and corruption. It smelt, rather, of spices and meat.

I stopped, studying a building that faced the street. There were no windows on the lower storeys, but at the top, two small glass-paned openings were propped open, giving out a loud stream of women’s voices.

I lowered my gaze to the ground floor: shutters on what was clearly a shop of some kind. My brain made a huge effort, and presented me with an explanation: The effect of desertion was merely because the shops were closed tight, and the men were at prayer. It was a holiday – rather, a holy day. Today must be Friday, the Moslem Sabbath.

The sound of footsteps echoed down the hard surfaces and started me moving again. I took care to walk at a steady pace, holding my body as if I not only knew where I was going, but was interested in nothing particular outside of getting there.

How I knew to do this, I could not think.

It was unnerving, as if one portion of my mind was simply frozen solid. I had no idea where I was going – where I was to begin with – yet I moved forward now as I had walked the precarious wall earlier: with the unthinking assurance that can only come from long experience. The analytical machinery of my mind also seemed to be missing on a couple of cylinders: To have had blood on my hands yet none on my garments suggested that someone (in that house?) had removed my clothing, surely noticing that I was a woman, yet then dressed me in what I knew was male clothing. Why had they done that? Similarly, I had lain in that bed for some hours with neither locks nor bonds, as if I was a guest rather than a prisoner, yet they had robbed me of my weapons – and then summoned the authorities: A pair of soldiers would not have happened down that alleyway by accident. Again, why?

I could not have given my reasons for wanting to put distance between myself and the house, but my body seemed determined to do so. And until I had evidence to the contrary, I could only trust that it knew what it was doing.

Some twenty minutes later, having come to the dead ends of four different paths, it was clear that letting my feet choose the way by turning consistently left – or right – only led to a standstill. Instead, I started looking for lanes that led uphill. And in a short time, I came to a more lively quarter with open shops. Men sat in some, all wearing the same calf-length, rough-spun robes but occasionally layered with a heavier burnoose. They wore a variety of head-coverings: Some had loosely wrapped lengths of cloth, others wore snug turbans that revealed the crowns of their heads and a single thin plait, some had the rigid caps called tarboosh or fez. The women picking over displays of onions and greens were for the most part veiled, though some went freely barefaced. They all haggled: over the cost of lemons, the measure of olives, the quality of tin cups. Colourful displays of garments and tools spilt onto the street.

I moved at the same speed the others did; my eyes were focussed at the same distance ahead; my robes were theirs – the men even wore the same yellow babouches. I dodged laden donkeys and responded to the warning ‘Bâlak! Bâlak!’ of their drivers and veered around displays and vendors without so much as a glance. I managed to walk past a pair of patrolling French soldiers without drawing any attention to myself. Several minutes later, I discovered that I had at some point removed my spectacles. I slid them through the pocket-slit in the djellaba, and when my empty hand came out again, it reached down to a display of fruit and deftly appropriated a small orange. As I proceeded through the streets, my pockets slowly filled, with fruit and a roll, a handful of almonds and a ball of twine, one decorative hair-pin, a small red Moroccan-leather note-book, a fat little embroidered purse plucked from a woman’s Western-style hand-bag, and a slim, decorated dagger that I kept inside my left-hand sleeve, fearing that if I put it into the pocket, within half a dozen steps it would slice its way to the cobblestones.

First an acrobat, now a pick-pocket. Had I escaped from some travelling circus?

I soon came to the explanation for this district’s relative bustle: a city gate, very new and strong-looking, ornate with mosaic tile (zellij, the translator in my head whispered). Beyond it was clearly a more modern part of this city, with men in suits, the sign for a bank, several horse-carts, even a motorcar. And: soldiers.

I leant casually against a wall. Armed French soldiers, with the bored stance and alert gaze of guards the world around. As I watched, they moved forward to intercept a man on a white mule, who freely handed over the immensely long Jezail rifle he held and continued inside. It would seem that arms were not permitted in the city. That might explain why my hand had met a revolver’s absence at my waist-band.

There was no way I could get past the soldiers without attracting attention, not in the clothes I wore now. Even were I to dress in a woman’s all-concealing shrouds, I would have to take care – although as with everything else that day, I could not have said how I knew that. My mind was in a shadowy netherland, but what knowledge I did retain was crystal clear. Uncertainty and inchoate fear seemed to sharpen the essentials, helping me to read the guards as easily as I had accumulated key possessions and walked unnoticed.

Still, until I knew more about my situation, I did not feel driven to break out of this suq. Whatever shelter, comfort, and time to ponder I might require, I could as easily find it here as out there.

I turned my back on the outer world, and descended once more into the dim-lit warren of the old town.

On the other side of a shop piled high with caged chickens stood a pocket handkerchief-sized café with a tureen of smoking oil and neatly arranged glasses of tea. As I had passed it before, my stomach vaguely let me know that its former queasiness was fading. Now, at the aroma of chillies and hot oil, my mouth began to water and I realised that I was weak with hunger. I dug into my pockets, then stopped: Fumbling with unfamiliar money, taken from a lady’s decorative purse, would be foolish. I spent a moment watching closely as a man purchased a small cornucopia of fried ambrosia, and forced myself to walk on.

At the next bit of blank wall, I surreptitiously drew out the purse, searching for the coin I had seen him use. There were two. I palmed them and put the rest away. Back at the fragrant food-stall, I nodded to the proprietor, lifted my chin at the glass case, raised an affirming eyebrow when his hand hesitated over a choice, and laid one of the coins on the tiny counter. I left my hand there until he slid some smaller scraps of metal into my palm, following them with a greasy handful of flat bread wrapped around an unidentifiable mouthful of spice. My jaws might have learnt table manners from a dog: Half a dozen sharp gulps, and the food was but a trace on my fingers – which I eyed, but did not lick: I needed to find a source of water, and soon.

In this same way, I obtained a bowl of extraordinarily hearty soup called harira, a sweet biscuit tasting of almonds, and two glasses of hot, syrupy mint tea.

The food did nothing to clear my brain, but it was little short of a miracle how it helped the shakiness recede.

And as if the suq’s guiding spirit had heard my plea, around the next corner was an open area where three of the diminutive lanes came together, which in any normal town would have gone unnoticed but here was tantamount to a village green. Set into one of the resulting corners was a magnificently tiled fountain, at the moment gushing water into a child’s brass pot. I waited while two women filled their jugs, then pushed forward to thrust my hands under the frigid clear water.

I could feel their disapproval, either because it was not done to wash one’s hands in a drinking fountain, or because I was (to all appearances) a man pushing into a woman’s realm, but I did not care. I scrubbed and clawed at my nails as if the stain were some systemic poison, and I kept on scrubbing even after my eyes assured me the skin was clean. I even splashed my face.

Finally, too aware of the waiting women, I drew back. In the centre of the open area, I held up my hands to reassure myself that the blood was gone. And for the first time, I noticed a faint indentation around the ring finger of my right hand.

I stared at it. I turned the hand over, then back, and felt a stir of rage. Take my weapons, yes, but steal a ring from my finger?

Had I been standing on the rooftop, I would have stormed the house, soldiers or no. But I had left that house hours ago; I’d never find it again.

Furious and mournful, I dried my hands on my robe and slipped back into the suq.

Since I was now both fed and cleansed, the next order of business was to find shelter against the night. The afternoon call to prayer had come and gone; in the short winter’s day, sunset would not be far off. And perhaps if I slept, my missing past might creep back. If nothing else, a private corner would let me paw through my few possessions, and my fewer memories, and consider where I stood.

The problem was, I had seen nothing that resembled an hotel. I had seen no hand-lettered Room to Let signs propped in windows (had there been windows). I had a vague idea that benighted travellers might be welcomed in a mosque or madrassa school, but that was far too risky for a woman in disguise. Even a caravanserai, or whatever the local equivalent might be, would be tricky. And although I spoke a couple of the local languages, I was loath to risk a demonstration of my ignorance by asking.

What I needed was another deserted building. Of which there seemed to be plenty, but I preferred one with a facsimile of a roof, and not on the point of collapse.

I kept walking, waiting for my bruised cortices to present me with an idea. A dull boom of cannon-fire shuddered over the town, startling a pair of egrets into flight, but it seemed to be merely a signal: The muezzins started up their sunset calls. More shops began to close. A wrinkled gent gave a friendly nod as he ran a chain through the iron loops on his shop’s door. Farther along, a shoe-seller picked up a basket filled with fresh-made babouches, and with the leather odour came a vivid jolt of memory: an avalanche of bright yellow slippers in a narrow lane / tannery smell and spice and sea-air / a donkey’s bray / men shouting / above it one man’s voice—

Then it was gone, and the shoe-seller was staring at me. I gave him an uncomfortable smile and continued on.

Across the way and down a few steps, a brass-worker was closing his doors on an Aladdin’s cave of gleaming metal and Mediaeval tools. His workshop opened, not directly off the street, but through a shallow arched entrance that provided supplemental display-space for his wares during the day.

My mind gave me a nudge. I walked on, bought a glass of orange juice from a man with one small basket of fruit left him, and drank it as I gazed back the way I had come, watching the brass-worker’s retreating figure.

Returning the empty glass, I walked on slowly, taking great care to recall my path. I lingered in deserted streets, I passed back and forth and circled about, until the dim lanes were going dark and the darker recesses were nearly black. I waited until a group of chattering men passed where I stood, and fell in behind them until we reached the brass-worker’s doorway. At the dark arched entrance, I took a step to the side.

My hands seemed to know, without benefit of sight, how to open a padlock with the straightened right earpiece of a pair of spectacles and a hair-pin. Yet another curious skill.

Inside, there were no lingering apprentices, no open courtyards to a family dwelling. A high window, gathering in the last of the day’s light, showed me the room: Banquettes along two of the walls, where customers would drink cups of tea, promised cushion for my aches; two gleaming eyes from a high shelf eyed me warily, but the resident cat stayed where it was. A patch of blackness beside the faint glow of the brazier proved to be charcoal, enough to keep me warm all night.

I had not realised how utterly wrung-out I was, until I stood in that safe place.

I barely made it to the cushions before my legs buckled, and there I sat, my knees pulled up to my chest, near to weeping with relief and exhaustion. If the soldiers had knocked at the workshop door, I would have flung myself at their feet.

I sat there a very long time before the trembling stopped.

The high window had gone dark, the cat’s eyes had vanished. The pain in my head, arms, and hip that I had kept at bay by movement and fear had taken over again, and it was an effort to work my hand into an inner pocket to pull out a piece of bread. I forced myself to eat it, then crawled over to add charcoal to the fire, lest it go out during the night.

By the flare of light, I examined my hands again, as if the dried blood might have returned. They were clean. I looked at my right hand, with its indentation, then at the left. The left hand was where Europeans in general wore a wedding ring; however, for some reason I felt quite certain that my people – Jewish: Wasn’t I Jewish? – put the ring on the right hand. That the narrow dent was from a wedding band. But why was the skin beneath it not pale? My hands were brown from the sun – much browner than the rest of my arms – and the colour was no different beneath the ring. Was I married? Had my husband died? Had he cast me out into the suq, for thievery?

I lowered my head to my knees, trying to think back over the day, trolling my memory for any kind of clue. I was in a North African city made up of an un-mappable tangle of tiny by-ways. Some of its buildings took the breath away with their beauty, their ornate tile-work crisp, their paint and carvings clean. Other houses were rotting shells on the edge of collapse, dangerous and stinking of decay.

One might almost think my damaged mind had created a town in its image.

Enough, I decided. I could do no more tonight. I was dimly aware that one was supposed to keep a concussion victim from sleep, but in truth, given a choice between staying awake any longer, and simply not waking up, I would take the risk.

I laid the decorative knife beside me on the cushion and tugged the hood over my face. As the world faded, again I smelt the faint aroma of honey.

CHAPTER THREE

THE CLIPACLOP OFA donkey’s hooves woke me. The room was black as a bowl of tar – but no: A faint glow came from one corner. Not a windowless cell, then; but where …?

Donkeys. The odour of smoke, and wool. A memory of mint on the tongue: the suq. I started to throw off the bed-clothes, discovering simultaneously that there were no bed-clothes and that my head strenuously objected to sudden movements. My fingers tugged at the rough wool, found it was a garment – ah, the brown robe from the hook in the small room. With that, the previous day slid into place: the dappled reality of wandering a labyrinth of dim, tight foot-paths, as if I had been set down into a world of tunnelling creatures. Into a beehive.

Shadowy streets and a shadowed mind.

Still.

I sat, pushing the robe’s hood away from my face.

The concussion hadn’t killed me, then. It was early: No light came from the high window. My surroundings had remained silent during the still hours, with no evidence of living quarters overhead, although after I had thrown more coal on the fire, the cat had roused itself for a bit of mouse-chasing before coming to settle beside me. And I dimly remembered a long echoing prayer, or song, as if some insomniac muezzin had decided to enforce the declaration that prayer is indeed better than sleep.

Despite that interruption, I felt rested. The pain in my head remained sharp, but the rest of me merely ached. I patted around the floor until I encountered my spectacles, which had been ill-fitting to begin with and were not improved by having been used as a lock pick: One of the lenses bulged against the frame, and the right earpiece had several unintended angles. I folded them away into my pocket, and raised my fingers to the turban I wore.

Not, I thought, precisely a turban. The cloth encircling my head felt more like a bandage, although with the robe’s hood up, it might look like an ordinary piece of head-gear – ordinary for this town, that is, but for a lack of the thin pig-tail many of the men wore. The part of my skull over my right ear seemed the most tender, which was perhaps related to the kink in the earpiece. All in all, I would leave the wrap in place for now.

Light would help. I dug into my garments for the box of French matches, which I had pocketed after lighting the oil lamp in yesterday’s cell. They were mashed rather flat now, since I had lain on them all night. There must be some kind of a lamp here. I stood, and as I did so, some small metallic object flew away from the folds of my clothing, rolling across the stones. I stifled the urge to blindly leap after it. Instead, I felt the remains of the box: three matches.

I lit one on the second try, and held it above my head. The flame burned out before I reached the lamp it had revealed, but I felt the rest of the way in the darkness. After giving the thing a slosh, to make certain it held fuel, I scratched my second match into life and nurtured the lamp to brightness.

A myriad of gleaming shapes shone back at me: stacks of brazen bowls, trays ranging from calling card–sized to sufficient for an entire roast sheep, bowls of similar variety, a dozen shapes and sizes of lamp. But the one I carried seemed to be the only one holding oil, so I took it in search of the rolling object.

There was a hole in the floor, a drainage hole (no doubt the source of the wildlife that had entertained the cat during the night) containing sludge so disgusting, not even the Kohinoor could have tempted my hand into it. Before I made the laborious effort of climbing back to my feet, I studied the shape of the stones themselves. Yes, a carved trough led towards the hole, but a settling of the paving stones suggested an alternative route, directly towards a workbench that rested on the floor. I set the lamp on the stones and laid my cheek to the floor, the cool stones startling another snippet of memory to the fore: cold stones / the lit crack beneath a door / red boots / a fire / rhythmic speech—

And then that, too, was gone.

But there was something small and shiny, under the bench.

My fingertips teased at the round smooth gleam, threatening to push it away for good. I sat back on my heels and reached for my hair, finding only fabric where my fingers had expected hair-pins. But, I did have one pin. I found it in my pocket, bent it into a hook, and pulled the elusive circle out.

A gold ring, accompanied by a sharp hallucinatory odour of wet goat. It was not the one missing from my own hand, for it was big enough around to fit my thumb. A man’s signet ring, very old and, judging from its weight and colour, very valuable. I held it to the lamp-light to study the worn design on its flat edge: a bird of some kind, a stork or pelican, standing on wavy lines that indicated water.

Not a thing one might expect to find in the shop of a brass-worker. But then, neither was it the sort of jewellery one might expect in the pocket of an amnesiac escaped circus performer.

But a pick-pocket? One who had run afoul of the police?

Or, did it belong to my missing husband?

I set the lamp on a clear patch of bench, and emptied my pockets down to the fluff.

I picked up the embroidered purse, noting that the clasp was still shut – the ring could not have fallen from there. I poured its contents out onto the age-old wood, coins and currency, all relatively new. BANQUE D’ETAT DU MAROC, they said, CINQ FRANCS; the coins were stamped with EMPIRE CHERIFIEN, 1 FRANC and 50 CENTIMES. One marked 25 CENTIMES had a hole in its centre.

So: Morocco.

I corrected myself: More exactly, this purse had been filled in Morocco. Still, it was evidence enough to be going on.

And the Arabic numbers, along with the spectacles and the modern rifles the soldiers had carried, suggested the twentieth century rather than the nineteenth – or the thirteenth.

Absently, I rubbed the currency about on the filthy wood, then crumpled it before returning it to my pocket: unlikely that someone with my current appearance would possess crisp, new bills.

In addition to the bits and bobs I had appropriated the day before, I found the following:

In the trouser pockets, grains of coarse yellow sand.

In the left-hand pocket, a chalky stone the size of a flattened walnut.

From the right-hand pocket I took a length of twine, snugly bound, and an object wrapped in a handkerchief. I unwound the worn muslin to reveal a length of copper pipe, four inches long and an inch across. The handkerchief was permeated with sand. Beneath the creases I made out the crisp lines of a long-ago ironing, but there were no convenient monograms or laundry marks. I examined the pipe; it contained only air. But when I wrapped it back in the cloth, then laid the bundle across the fingers of my right hand, they closed comfortably around it.

My left hand remembered all too vividly the sensation of driving a knife through flesh. My right hand, it would seem, provided the support of brute weight.

So: a pick-pocket accustomed to nasty fighting.

Had I killed a man to steal his ring?

I dropped the primitive knuckle-duster into its pocket, then took a closer look at the quartz-like stone. Other than being of sedimentary origin, and vaguely reminding me of building material although it was of a size that more invited the hand to throw, it told me nothing – my store of odd knowledge apparently did not include petrology.

The stone and everything else went into the pockets they had come from, with the exception of a handful of dried fruit, the decorative knife, the empty purse, the scissors, and the ring. The fruit I ate; the empty purse I tossed onto the brazier coals, pushing it down with a stick; the rusted scissors, which had jabbed me continuously the previous day, I abandoned on a high shelf; the ring I sat and studied.

The problem was, everything I took from my pockets had seemed possessed of immense mystery and import, as if the stone, the pipe-length, the grains of sand were whispering a message just beneath my ability to hear. When everything meant nothing, it would appear, even meaningless objects became numinous with Meaning. The date pip I spat into my palm positively throbbed with significance.

It was damned irritating.

Another donkey went past, a reminder that daylight could not be far away. I had to leave this place, lest I be driven to make use of that pipe-cosh and the stolen knife.

First, I rescued a length of leather from a stack of the same – polishing rags, it would seem – and fashioned a rough wrist-scabbard for the stolen knife. I took a last look at the ring, sitting by itself on the workbench, then caught it up and dropped it into my breast pocket.

My hand stopped. Breast pocket: I’d forgotten I had one.

It was the size of my palm, with a flap, currently missing a button. I fished around inside, feeling its emptiness – and then a faintly non-cloth sensation brushed my fingers. I drew out a tiny scrap of paper, smashed flat by having been slept upon.

I picked it open. The paper was near-translucent onionskin, and had been wet at some point, but I managed to get it flat with only a small tear: the corner of a larger page, a triangle three and a half inches high and two and a bit wide. There were a series of pencil squiggles on it, lines as pregnant with meaning as the grains of sand and the date pip:

It looked like a capital A drawn by a small child or the victim of a stroke, although oddly precise. Probably it was the result of a piece of paper and a stub of pencil riding together in a pocket.

I turned the scrap over. Then rotated it.

At first glance, the string of interconnected curves seemed as devoid of meaning as the accidental A on the reverse. But I knew they held some intent beyond mere idiotic self-importance, and indeed, once I shifted the direction of my gaze to read from right to left, the pencil scribble became words, in crude, even childish Arabic writing: the clock of the sorcerer.

I sighed.

Pressing the scrap into my purloined note-book, I put it and the ring into the breast pocket, stitching the flap shut with the ever-useful hair-pin. I arranged the cushions as I had found them, pushed the purse’s metal clasp deeper into the coals, and blew out the small lamp. When I had let myself out, I padlocked the door and walked into the suq in search of a sorcerer and his clock.

I found many things during the course of the day. My first goal was food and drink, followed by thick stockings and a heavy woollen burnoose to keep out the penetrating cold. As I walked, the chorus of muezzins woke the town, and soon the streets burst into life, shutters opening to displays of colour and enticing aromas – not the least of which was the damp soap-smell that wafted from a hammam, a place I dared not even think of entering, no matter how much the pores of my skin craved a scrub-brush.

By mid-morning, I was warm, fed, and gaining in confidence: I had negotiated several transactions without arousing suspicions, I had passed two more pairs of patrolling armed soldiers, and my tongue was producing a reasonable facsimile of the local accent. Yes, a restoration of memory would be nice, but as the immediate needs of survival became less pressing, the suq provided an endless variety of distractions, for all the senses: I saw tailors and carpenters, carpet-makers and silk-weavers, book-binders and jewellers, purveyors of leather footwear and ceramic pots and elaborate wedding head-dresses, men embroidering the fronts of robes or trimming the beards of reclining customers. My nostrils were teased by the odours of frying onions and baking bread and the cloud of aromas from the spice merchants, in between being repelled by the miasma from butchers’ shops and malfunctioning sewers, entertained by the sharpened-pencil smell of fresh cedar and the musk of sandalwood, caught by the clean reek of fresh leather or the dark richness of roasting coffee beans, and educated by the contrasts of wet plaster with crushed mint, donkey’s droppings overlaid by fresh lavender. My ears similarly passed from one aural environment to another: a chorus of schoolboys from over the walls of a madrassa and the sound of a grain mill grinding below street level; the rhythm of soft-soled footwear against compacted dirt beside the ceaseless, many-noted ting of brass hammers from a dark den; a pure voice raised in song giving way to the rasp of small saws from an inner courtyard.

The populace ran the spectrum from African black to Mediterranean olive, with the occasional Nordic features and even blue eyes looking out of Arab brown skin. Jews, Arabs, Europeans, Sufis, each in a different form of dress. Transportation was mostly tiny sweet-faced donkeys and sullen mules, but I also saw a few horses, a handful of wheel-barrows, two camels (at a distance, not within the suq streets), and one heavy-laden, flat-tyred bicycle being used to deliver lengths of bamboo.

And the wares on offer! One street held shops displaying tall cones of varicoloured powder, from the deep red of paprika to brilliant yellow turmeric, interspersed with vendors selling bags of sticks, leaves, seeds, and what appeared to be sand, bowls of dusty blue chunks of indigo, and carefully arranged hillocks of mice skulls and desiccated lizards. One shop displayed hundreds of prayer beads on its three walls – ivory and amber, lapis and coral, sandalwood and ebony. Its neighbour held teetering stacks of cylindrical tarbooshes, or fezzes, mostly red, with tassels of every colour imaginable.

Few of the shops had signs. I took care to read any that did, and once spotted the word horloge on a display of timepieces near a gate at the southern edge of the suq, but there was no mention of sorcerers.

Apart from the absence of magicians’ timepieces, the town held a richness of sensory stimulation and information, when a person had nothing to do but wander and listen. And as the morning wore on, I found that the previous day’s sense of confusion had settled considerably.