8,39 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Garnet Publishing

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

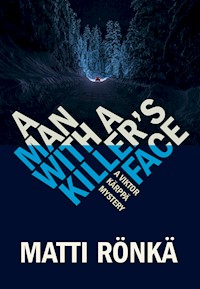

According to his dossier in the archives of the Soviet Special Forces (in which he once served), Viktor Kärppä has the look of a killer . Except he really isn't one, notwithstanding his ability to sever a man s windpipe with his hand. Despite his messy, ambiguous past, Kärppä now has an orderly life as an entrepreneur in Helsinki, and likes it just fine that way. His new girlfriend Marja, an academic, also prefers things as they are tranquil and uncomplicated. Kärppä helps members of the downtrodden Ingrian community Russian-speaking ethnic Finns who have emigrated from their native Russia back to Finland adjust to their new surroundings. Thus his dream of a quiet life is regularly thwarted by Finns and Russians on both sides of the law who know too much about him. When he accepts a well-paid case to locate an antique dealer s missing Estonian wife, Kärppä discovers the woman is also the sister of a notorious gangster. So begins his descent into an international criminal underworld with all the trimmings: drug lords, former KGB operatives and sundry other heavy characters. Suddenly nothing is as it was not least with Marja, who has become all too aware that her man s line of work is unlikely to bode well for a healthy relationship…

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2017

Ähnliche

A Man with a Killer’s Face

First published in Great Britain in 2017 by

Periscope

An imprint of Garnet Publishing Limited

8 Southern Court, South Street

Reading RG1 4QS

www.periscopebooks.co.uk

www.facebook.com/periscopebooks

www.twitter.com/periscopebooks

www.instagram.com/periscope_books

www.pinterest.com/periscope

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10

Copyright © Matti Rönkä, 2017

Translated from the Finnish Tappajan näköinen mies (Gummerus 2002) by David Hackston

This work has been published with the financial assistance of the Finnish Literature Exchange (FILI).

The right of Matti Rönkä to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise) without the prior written permission of the publisher, except for the quotation of brief passages in reviews.

ISBN 9781859641781

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

This book has been typeset using Periscope UK, a font created specially for this imprint.

Typeset by Samantha Barden

Jacket design by James Nunn: www.jamesnunn.co.uk

Printed and bound in Lebanon by International Press:

Pakila, Helsinki

The woman said her name to her reflection: ‘Sirje’.

Her mouth moved in exaggerated emphasis, as though she were talking to a deaf person. She applied a swipe of lip balm, then pressed her lips together, pursing and releasing them in turn.

She was a dark-haired, almost beautiful woman. When they met her, men never knew whether to call her a girl or a woman, though she was already old enough to be the kind who enjoyed reading glossy women’s interior-design magazines.

Sirje brushed her smooth, shoulder-length hair, finally seemed content after the umpteenth stroke of the brush, then hid her hair in a thin, green woollen scarf. She buttoned up her coat, rocked back and forth from her toes to the heels of her boots, flicking the buckle on her satchel open and shut in the same tempo.

Then Sirje let out a sigh, pulled on her leather gloves, working the sheaths of each finger into place until they sat snugly, and made to leave. At the door she took one last glance in the mirror, but didn’t look back around the hallway or the house that had become so familiar; she didn’t inhale its scent, didn’t pause in concentration until her ear finally homed in on the low clack of the grandfather clock in the living room and the hum of the fridge-freezer in the kitchen.

No; she merely smiled at the mirror, mouth slightly askew, as though she were smirking at a private joke. She carefully clicked the door shut, locked it, shutting off the house’s dry, centrally heated air from the sharp, damp cold outside, and walked across the garden to the street, her boots crunching in the snow.

Kesälahti, Eastern Finland

Yura’s job was simple: stay awake. That was it. That’s what Karpov had told him to do, and Yura had given his word. Maybe the job was just too easy. Even Yura yearned for something a bit more demanding.

A portable worksite cabin had been brought inside the industrial warehouse to form a makeshift office; that’s where Yura was to sit. To sit and drink tea from a Thermos flask, eat bread, tinned meat and chocolate. And smoke. ‘There’s plenty of smokes in there, so long as you don’t torch the building,’ Karpov had smirked.

Funny boss, Karpov. Sometimes he chatted and rambled in Finnish, of which Yura couldn’t understand a word. Still, even in Russian he made peculiar jokes and laughed too much. He was an odd character. And besides, a place like this, nothing but sheet metal and concrete – how could this place go up in flames?

‘If something happens, Yura, then you call me. But remember: stay awake, all the time, all night, all day, all evening.’

Karpov had harped on, repeating the same thing over and over, and Yura had nearly snapped at him: ‘Yes, all right! Got it.’

Needless to say, Yura had dozed off. And when he woke up, he knew at once that things had turned sour – very sour. The frozen air had pushed its way into the office, and his sleepy skin felt the chill.

The warehousedoors are open, Yura thought, though his mind was as stiff with sleep as the gearbox of a truck jumpstarted in a snowdrift, beating the engine oil into motion one cog at a time. Is oil an amorphous material? Surprised that he even knew such a word, Yura shook off the thought, which was to be his last.

As a child, Yura hadn’t dreamed of becoming a cosmonaut or a teacher or even an engine driver or a successful criminal. Other kids had always been faster, stronger, smarter, and Yura knew this only too well. He was happy as long as he could eat a decent meal regularly, drink himself into oblivion, get laid every now and then and find a mattress and a blanket for the night in a relatively warm room. Karpov had taken good care of him these last few years, and Yura didn’t have any great plans for the future.

But he had certainly imagined living longer than twenty-six years. This was not good, not at all. A man was standing a metre in front of him, a tall man in a blue Adidas tracksuit, a hat on his head, his hand raised and pointed steadily at Yura. And in his hand, fifty centimetres from Yura’s forehead, was a black pistol.

Tallinn, Estonia

The room was tidy, open and brightly lit, though it had originally been built as a storage space, a garage or workshop. The walls had been plastered and smoothed, then painted white; the grey steel shelves were sturdy but unremarkable, and the tidy concrete floor sloped gently and immaculately towards the floor drains.

Working around a set of melamine tables, wearing white coats, were five men and one woman, each weighing measures of white powder into plastic bags, sealing the mouths of the bags and wrapping them in aluminium foil. They worked as though at a conveyor belt in a production line, silently and efficiently.

In the middle of the room stood a man, his posture guarded and calculated, doling out commands. ‘Move the boxes of mobile phones over there. Tidy up that package, lads, and let’s be bloody careful with that powder.’

The man was neither old nor tall, and his voice wasn’t loud; but he was used to ordering people around, and he clearly relished it.

His employees were happy to obey him. They knew their boss was sensible and wise, cunning even. He had been loyal to his people – something pretty rare in this business. Many bosses took a cut for themselves and stabbed their business partners in the back or took unwise, insane risks – and many ended up abusing the stuff themselves.

But not this boss. He had dealt in women, copper, tin and firearms as well as passports and visas. But it was just business, services and merchandise for sale, nothing more, he was keen to remind them. His own wife, pistols and papers were for his exclusive use. He had never even tried drugs, and didn’t find anything strange about this in the slightest.

Sometimes he gave a contented sigh at the thought of how nice and clear-cut it was, dealing with money and stolen goods. As for women with whips, hormones to make your muscles bulge and substances that mess with your head – he didn’t like that. Money kept flowing in, much more than he would earn in small-time petty theft.

Transportation, packaging and storage, logistics right the way from Afghanistan to Russia, onwards to Tallinn and from there into Finland, the entire chain of command rolled, smooth and slick, from one cog to the next. And on the way, the opium of the poppy fields was refined into pure, high-end heroin.

The small man with the upright posture was proud of his business.

Sortavala, Russian Karelia

Anna Gornostayeva tested the soil with her finger, then watered the geranium. She nattered away to herself, though she’d often noted sardonically that around here you only needed your mouth for eating. There was nobody to hear her chitchat except the flowers and the photographs, no dogs or cats in the old house – and no mice either, thank goodness.

She straightened the curtains and ran her hand along the smooth, embroidered tablecloths, then wondered whether or not to give the rugs a shake; but she knew there was no dust in them to shake off. Why, I’ve got to keepa tidy house, Anna Gornostayeva thought. Life needs a structure, a rhythm to hold on to.

From the large pot on the stove, which was always warm, she ladled some hot water into a bucket, cooled it with water from the pail, dampened a threadbare cotton towel that had now been designated a rag and began wiping away the imaginary dust from the photographs in the bedroom.

‘Niilo, Nikolai, my little Kolya,’ she whispered, tenderly caressing her husband’s photograph. She berated him gently: ‘Why do you still insist on turning up in my dreams…? Stay away, will you?’ Then she replaced the photograph atop the chest of drawers. The man in the image had a straight nose, and his face was soft even without airbrushing. His eyes – she remembered them above everything else. She could remember them even without the photograph: eyes like those of an innocent forest animal.

Those same heavy eyes appeared in the boys’ photographs too, images taken during their time in the army. The shine of the visors on their peaked caps and the stiffness of the thick fabric of their uniforms recurred through the decades. Their chests were laden with medals and accolades – their father had the most impressive collection – and, although the photographs were black-and-white, you could sense the deep, festive red of the stars on each of those medals.

Anna Gornostayeva didn’t complain. At this age, she was used to being alone; she even enjoyed it, though dizziness and a strange chest pain often took her by surprise and gave her a fright. But now she felt strangely restless, and didn’t know why.

Of course, the boys usually telephoned her and worried about her: ‘Don’t chop firewood by yourself, and don’t go climbing up that ladder either. Why can’t you just heat the house with the electric radiators?’ They chided her and bossed her around as they would a child. They meant well, of course, but you couldn’t take them all that seriously, Anna chuckled to herself. After all, she was a grown woman, her mind intact, a woman who had lived through the war and all that had followed.

But nothing terrible could have happened to the boys, she reasoned. Alexei will surely get on well enough in Moscow; he has a good wife, his son is grown up and things at work seem fine. Viktor has been used to looking after himself from a young age. Finland is a foreign country, of course, but that’s where he wanted to go. He managed to get in, and it always seems that his life there is fine and dandy.

Don’t worry, Anna told herself. There’s no point spending the spring worrying about the autumn rains. And if you spill the milk, you can milk the cows again tomorrow… Proverbs started popping into her mind, so much so that she lost her train of thought and told herself out loud not to be so silly.

She started to polish Viktor’s prizes: small gleaming cups, spoons and round medallions attached to ribbons. Her left arm ached. Have I been sleeping awkwardly and caught a chill? Anna Gornostayeva wondered.

1

I noticed the man some way off. He was striding towards my office with shallow steps, like an orienteer whose next flag was on the edge of my desk. I took my feet off the desk, squinted and tried to follow the dark, featureless figure. Against the light, Hakaniemi Square looked bright. The sun shone across the square; the sight was like a faded photograph in a family album titled The family on a square in Agadir.

Many of my clients hesitate at the corner of the square or the narrow strip of park – nothing but sand, a few benches and a tree – and meander round to my office. They often wear a fur hat and a dark overcoat, and need help with a nationalization application or with filling in housing-benefit forms. I help them.

Then there are those who are Finnish builders, truck drivers or fitters, men whose wives, fifteen years their junior, have had enough of their red-bricked semi-detached prisons in deepest suburbia. Irina or Natasha or whatever their names were had packed up their things, taken the kids and headed back to their families in the Verkhoyansk district. It’s my job to track down the runaways.

A few clients might pull up on Viherniemenkatu in their Mercedes and BMWs without the slightest care. They leave the engines running on the double-yellow lines and leave their girls in leather skirts to keep an eye on the furry dice. These are businessmen whose staff have been seized, deported or taken into rehab. They might need a courier service or someone trustworthy to go over their purchase conditions. I have an honest face.

This client was something else. I didn’t have time to give the matter much thought before he was inside, without knocking, striding the few steps from the street into my office.

‘Viktor Kärppä…’

The sentence was left unfinished, without a question mark, and hung in the air like a haiku.

‘That’s me,’ I nodded and tried to look grateful and businesslike. The man’s appearance was neat and clinical: pressed, dark-grey trousers, the kind of black shoes that fashion magazines called ‘sensible’ and a green oilskin trenchcoat that had probably never seen a sea breeze. The man clasped his cap and gloves in one hand and set his rectangular briefcase on the floor between a chair and his leg. Ex-military, I guessed, but which army? A visiting businessman? A solicitor from an entrepreneurial organization, or an inspector from the city council?

I was hoping the man might be a client. I tried to have as little to do with society as possible. The police were the only state officials I had any contact with, and a regular policeman wouldn’t have come alone. The man was too old to be a field officer for the intelligence services, and besides, there was no stripped, modest trademark Volkswagen Golf parked outside.

‘Aarne Larsson,’ he introduced himself. ‘I understand you can take care of certain, shall we say, problems.’

Even his voice was dry. It wheezed in his parched throat like the grate of snow beneath a set of unwaxed skis. His presumption was more or less factually correct, I suppose. I decided not to bother giving him any specifics.

‘I’ve got a problem, a rather unfortunate situation… Well, to be blunt: my wife has disappeared.’

Larsson was eyeing up my office. From the bookshelf he picked up The Concise History of Finland and volumes V and VI of the red-covered Encyclopaedia of General Knowledge. I was annoyed that I’d just returned the first volume of Pentti Saarikoski’s biography to the library; now that would have looked sophisticated lying open on my desk.

‘You might be able to help me, using your… contacts. You see, my wife is Estonian. She moved to Finland in the early Nineties,’ the man explained, his speech slow but deliberate.

‘I hear you have an extensive network among people who have moved here from the former Soviet Union,’ he said, his grey expression fixed on my eyes. I couldn’t tell whether he meant this as an accusation or a compliment, so I said nothing.

Larsson sat down in the better of my client chairs. Spring sunshine gleamed on the linoleum floor, baking old stains that refused to be wiped away. The previous tenant of my office had been from a local trade-union division, and I’d bought the union secretary’s desk and filing cabinets after realizing they had left permanent dents in the flooring. The generous trade unionists had thrown a few more bits of ancient paraphernalia into the deal for posterity. The shoes of hundreds of visitors had scuffed the linoleum in precisely the same spot and left indelible black streaks across the floor.

I looked back at Larsson, trying to appear honest and expressionless, and waited. The silence heightened the tick-tock of the Chinese alarm clock on my desk. A voice on the radio was reading the shipping forecast in humble, mellow tones. When it reached the island of Gotska Sandön, I decided to speak.

‘Perhaps you could give me a few basics first, then we’ll see whether or not I can help you. This is all confidential, of course. I won’t use this information for anything else, even if you decide not to hire me.’ It was my standard opening line, and I knew it by heart. I opened my notebook.

‘I’ve already made notes of all relevant events and background information,’ Larsson cut in. He had obviously decided to take control of the situation from the outset. He flicked open his briefcase and handed me a sheet of paper, neatly printed out and protected by a brightly coloured plastic sheath.

‘This should give you all the facts,’ he said, and took out his glasses.

I read the lines of justified text very carefully. Larsson was no civil servant; he owned a second-hand bookshop on Stenbäckinkatu in the Töölö neighbourhood. ‘Near the old sporting association building. Well, it was probably before your time…’

‘Not at all, I go swimming there sometimes,’ I said.

‘I specialize in historical literature, political movements, that sort of thing. I don’t deal in prose at all, or any other modern fiction for that matter,’ Larsson continued unwaveringly, studying my face as though trying to discern which section of his text I had reached. He didn’t say this in mockery or disdain – but it was clear that he respected facts, not fiction.

From his date of birth I calculated that Larsson was in his sixties, and that Sirje, his missing wife whose name I now read for the first time, was thirty-five years old. They had been married for six years and had no children. Larsson had been married before, but this had ended in divorce. His ex-wife and high-school-aged son lived in Lahti.

Larsson had dutifully provided his home address. I tried to place the street, and judging by the door number – without a letter to indicate a stairwell – I concluded that he lived in a detached house in the Pakila area of Helsinki. There was also mention of a summer cottage in Asikkala, and he had listed a small group of relatives and business contacts. The document was a typed-up version of the notes I had been ready to take.

Larsson bent down and took another white envelope from his briefcase. From it, he produced a photograph. For the first time he seemed slightly wary. ‘This is Sirje. It was taken last summer…’

I took the photograph. The dark-haired woman was looking directly at the camera. The wind had blown her hair in front of her face, and she was about to brush the loose curls from her cheek. Her mouth was set in a half-smile. Behind her you could see rocks, the shoreline and the crashing of waves. Sirje’s face was pleasant, her eyes dark; but her gaze was somewhat downcast, unassuming and modest rather than self-assured.

A memory from the past caught me off-guard, bored its way through my concentration and pricked my mind, leaving me unsteady, wired, light-headed. Pine needles on the path through the island in Lake Ladoga, the grey sand on the shore, the girls in bare feet. Everything seemed fresh and crisp, as though these emotions and sensations had been suddenly taken from a freezer and left to thaw. I tried to clip the memories before they had a chance to focus, to join together and find the coordinates in my mind, then tug at my chest with longing. I forced myself to return to the matter of Aarne Larsson and the photograph of Sirje Larsson.

‘An attractive woman.’

Larsson’s look of bewildered satisfaction took me by surprise. I placed the photograph on the table and reread the paperwork he had drawn up.

‘When did your wife disappear and when did you realize she was missing? Were there any particular circumstances under which she disappeared? I assume you’ve been in contact with the police?’

‘Sirje disappeared on 6 January. I was at the bookshop. She’d left home some time that afternoon without mentioning anything in particular. And she didn’t take anything out of the ordinary with her. I waited that evening, asked friends if they’d seen her, called her family in Tallinn, then called the police and reported her missing. No one seems to have seen her. I’ve tried hotels, border controls, ferry terminals, the airport. There’s nothing; not a trace.’

Larsson spoke as though he were reciting a prepared statement. He sat quietly, upright; only his voice seemed reticent.

‘And the police simply called off their investigation. I tried to reason with them and lay down the law, but they all but laughed in my face. They made it abundantly clear that a missing Estonian woman was not worth their time. They didn’t say as much, but that’s what they meant.’ Larsson’s voice tightened. ‘Let the criminals sort out their own mess – that’s what they were thinking. But I know Sirje wouldn’t ever get involved in anything illegal. And that’s why I’ve come here. I hope you can find her.’

Larsson could see me staring at Sirje’s details in the paperwork he’d provided. At first I’d just glanced over it. Now I understood why the police had reacted the way they did. As though reading my thoughts, Larsson said, ‘Yes, Sirje’s maiden name is Lillepuu. Her brother is Jaak Lillepuu.’

2

Gennady Ryshkov waved Sirje’s photograph and shook his head. ‘Jaak Lillepuu’s sister? Never met her. But I don’t use the Estonian girls, and I don’t know them. I’ve never seen this one working the streets in Helsinki.’

I snatched the photograph from Gennady’s fingers and put it back in the folder. Ryshkov lit a cigarette and flicked the ash neatly into a round, copper-coloured ashtray with the words lahti special embossed on the bottom. This, too, I had inherited from the trade unionists when I’d moved into the office. The chain round Ryshkov’s wrist jangled with the motion of his cigarette, and other flashes of gold came from two rings, his watch and one of his incisors.

‘I’d still do her, though. I mean, if I had to, I’d give her one,’ Ryshkov proclaimed. ‘Only problem is, she’s Lillepuu’s sister. I wouldn’t lay a finger on her. I wouldn’t even touch his sister’s best mate.’

‘Don’t mock my client. You’ve put on weight, Genya,’ I said, teasing my employer like an elder brother. ‘You must have either a good memory or a vivid imagination to talk about getting laid. Or do you test your goods first? Get the lay of the land, if you know what I mean? You certainly don’t get any for free…’

Ryshkov smoked quietly, then stood up and walked towards me, stretching like a hundred-kilo cat. Only the purr was missing. His belly sagged over his belt; he was the sort of fellow who had eaten whatever he pleased as a young man, but now, in middle age, his stomach protruded outwards – though the rest of his body was relatively slender.

He approached me and stared at me with his deep, black, perpetually dark eyes. I was worried I might have miscalculated his tolerance for a spot of humour. You never really knew what kind of mood Ryshkov was in. He always spoke in the same monotonous way, three words at a time, his face fixed in a single expression.

‘Then I’ll stop screwing them altogether – if I can’t get any on the free market,’ he scoffed, talkative by his own standards. He stubbed out his cigarette and lifted his smart suede jacket, then yawned. A bluish tinge of stubble peppered his cheeks. I’d never seen him looking energetic.

I did a lot of work for Ryshkov. I drove cars from Helsinki to Vyborg and St Petersburg, brought women to work in Finland, rented apartments and acquired goods for his various companies. I was always paid on time, and Ryshkov always kept his word. But I never understood what made him tick. I couldn’t quite trust him.

Perhaps ‘trust’ sounds too grand. Even a crook can be trustworthy when you get to know him and reckon with his shortcomings. All I knew about Ryshkov was that he came from Moscow, never talked about his parents, couldn’t remember his siblings or his home, never mentioned his school or his time in the army. I’d tried to ask, but he never offered any kind of explanation. I didn’t really know what he thought of my nosy questions – or of me, for that matter. Now I got the feeling he was thinking about the disappearance of Sirje Lillepuu and drawing his conclusions.

‘It’s been the same for the last twenty years.’ When he realized I hadn’t quite understood, he added: ‘My weight.’ He shook my hand as he left, and said he needed to pop into one of his restaurants downtown before heading off for the border crossing at Vaalimaa, then on to St Petersburg. I didn’t ask what he was going for.

Ryshkov stopped at the door and turned towards me. He was playing with his car keys, letting them glide between his fingers, dangling the Mercedes star insignia on its golden chain like a cross on a rosary.

‘Listen up, country boy. Be bloody careful. I’ve had my disagreements with Jaak Lillepuu, but we’ve sorted them out. It was a heavy case, pretty nasty too. Lillepuu is in a different league from your Karelian pimps and drunken petty criminals.’

I couldn’t remember Ryshkov ever warning me of anything before.