Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Saqi Books

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

A story about family, ageing, fresh starts and the beautiful things that happen when we least expect them to. Suad misses her husband. He died unexpectedly during an argument at work, and she never got to say goodbye. But Suad knows she is lucky. Her three children have promised to look after her. After several false starts, Suad receives a warm welcome from her oldest son and settles down with his family in the countryside. Everything goes smoothly – at first. Her grandchildren love her crunchy, homemade falafel and watching TV together. But as time goes on, things between Suad and her daughter-in-law grow tense. Soon, her daughter-in-law stops giving her lifts into town. She accuses Suad of interfering with how she raises her children. Then she won't talk to Suad. Finally, she asks her to leave the house. For the first time, Suad is on her own. Determined to make the best of it, Suad makes a new life for herself. How can she budget for just one person? How can she fill the long hours? And will her new neighbours warm to her?

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 111

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2025

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Leila Aboulela is an award-winning writer whose work has received praise for its exploration of identity, migration and Islamic spirituality. Her most recent novel, River Spirit, was shortlisted for the HWA Gold Crown Award for Historical Fiction. Aboulela grew up in Sudan. In her mid-twenties she moved to Scotland, where she now lives.

ALSO BY LEILA ABOULELA

River Spirit

Bird Summons

Elsewhere, Home

The Kindness of Enemies

Lyrics Alley

Minaret

The Translator

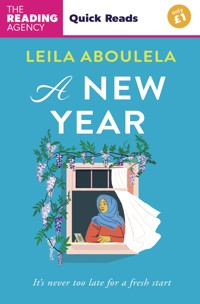

LEILA ABOULELA

A New Year

A Quick Reads Original

Chapter 1

When Suad’s husband died, her three adult children came home. Her two sons arrived first. The youngest came by train and the eldest flew to London from Scotland. Suad’s daughter travelled across the world from Indonesia. The children filled the house and surrounded her with love and support. They promised that they would look after her. They would never allow their mother to become lonely in her old age. Suad felt comforted and relieved. They were good Muslim children who would honour her forever. She was worried about being alone, but they would never throw her in a nursing home. They would not abandon her.

The death of Suad’s husband, Sherif, had been a shock. In the morning, he showered, dressed and went to work. In the afternoon his body was in the morgue. He had been a maths teacher close to retirement. Sherif died in the staff room in the middle of lunch. When Sherif gasped and keeled over, the staff called an ambulance. It did not arrive quickly enough.

Suad’s whole life had been turned upside down. Sherif had been her soulmate. He had been the one with the big plans but they talked through the details together. Suad kept Sherif grounded. He gave her the everyday strength to carry on.

Sherif had always been the one who explained things to Suad. He had dealt with all the difficulties – their immigration paperwork and how to live in a foreign country. They had moved to Britain to escape war. Now it was as if the horrors they had fled had reached her anyway. Suad was crushed and breathless. She swayed from the weight of the loss. Her man was gone. Suddenly. The end.

But no, Suad still had to break the news to their children. She called her eldest son first. Hamza was an engineer. He lived with his young family in the Scottish countryside. It did not completely surprise Hamza that his father would collapse. Sherif was seventy-three years old. He had been overweight, overworked, with high cholesterol, high blood pressure and a history of smoking. But death? Hamza was not expecting that.

Hamza had imagined they would rush to the hospital and spend days in intensive care. ‘Yes, but it was not like that,’ said Suad, starting to weep.

‘Call Nesrine and Mazen,’ Hamza said to Suad. ‘I will get the next flight. I doubt Nesrine will be able to come.’

Nesrine, Suad’s only daughter, lived in Jakarta with her husband. Two years ago, she had shocked her parents by insisting on marrying a divorced man twice her age. Suad knew how upsetting the call would be. It took a heartbeat for Nesrine to absorb the news. Then she became hysterical.

Crying bitterly, Nesrine insisted on coming home.

Suad’s conversation with Mazen, the youngest, was the hardest. He was studying medicine in Birmingham and his father had been particularly proud of him. ‘I don’t understand what you’re saying,’ Mazen said. ‘Where is Baba now right now? Is he at work or the hospital?’

Suad raised her voice. It was wobbly but loud. ‘In the hospital. The school phoned me. They tried to save him. The school nurse did CPR until the ambulance came.’

‘Okay. The hospital will know what to do,’ Mazen said.

‘No, Mazen. Your father’s dead. Listen, come home. Go now to the train station and come home.’

‘Mama, you should be with him. Get off the phone and talk to the doctors.’

It was a horrible conversation.

Mazen still refused to believe the news.

His flatmates helped him catch the train to London. He was the first to arrive. Hamza flew from Inverness and landed at Heathrow airport after dark. Nesrine was the last to arrive. It took her almost thirty hours to reach home and she missed the funeral.

It was Muslim tradition to go ahead with the funeral as soon as possible. The funeral prayers were held in the mosque the day after Sherif’s death. Mid-week, straight after the noon prayer. Understandably, not everyone could get away from work or studies. There was a decent number of people, but the prayer hall was not overflowing. Later, when Suad shared her disappointment with the children, they were horrified that she noticed. They did not understand why it mattered.

‘You only have one funeral,’ Suad said. One life. Death was huge. Death was final. Death was the experience everyone hated and everyone had to taste.

Suad wanted all of Sherif’s students to be at his funeral prayers. She thought they should all have been at the mosque, paying their respects to their teacher and praying for his soul.

It was Suad’s friends who filled the women’s section of the mosque. Women she had known since she first moved to Britain forty years ago. They were all there. Every single one of them who was still alive. Many of these women could now only pray sitting on chairs. Some of them had survived awful illnesses. Some of them were already widowed.

Suad burst into tears when she saw the coffin. She could not hold herself up anymore. If her best friend Najla hadn’t supported her, she would have fallen to the floor. Suad’s body felt empty and dry. It was like being in the middle of storm.

Sherif’s death was now real, Suad could not deny it. He was really going away. He did not belong to her anymore. He did not belong in his own home; he did not belong in the school where he taught. Even in the mosque where he had prayed, they were bidding him goodbye. When Suad cried, she felt helpless as if she were no longer a responsible adult. She struggled to see or hear.

When she was with Najla and her friends,

Suad gave way to grief. But with her children, she made a huge effort to stay calm and reasonable. The children must always come first, that’s what Sherif had said. Everything Suad and Sherif had done had been for the children. It felt right that they were here now, with her. They had left studies and work. They had left partners and children.

It was painful not to be able to tell Sherif that the children came. There were so many things she wanted to ask him. Was it okay for Mazen to skip his lectures? Should she be the one phoning distant family or should Hamza, as the eldest son, do it? It felt crazy to think that Sherif could not answer. It was unfair that she was expected to continue alone.

Suad could not sleep. Sherif’s smell was still on the sheets, but the bed was cold. She could not hear him breathing or snoring. It didn’t make sense. It was all too quick. She phoned Najla. She had said call any time.

When Najla picked up, Suad said, ‘I can’t bear the pain. I am not well at all.’

Najla said, ‘Pray for him, Suad. He needs you now. He can’t pray. He can’t do anything for himself. Ask Allah Almighty to forgive him. To wash away all his sins. To fill his grave with light. To grant him peace in that dark, lonely place where we are all heading.’

It comforted Suad to hear such words. Najla was right. Sherif had left against his will. He had gone and Suad would go there too one day, sooner or later. She must be patient. She would take comfort in her wonderful children. They were well brought up; they understood their duty towards her. They would look after her. They would not let her down.

Chapter 2

The day after the funeral, the children settled around their widowed mother. Hamza spoke to his work mates on the phone. Nesrine’s friends came over. Suad glimpsed her youngest son, Mazen, in the garden talking to the neighbour across the fence. Everyone knew that Sherif was dead now.

Around the kitchen table, the children talked to each other while Suad heated up the food the neighbours had brought over. Suad was never going to heat up food for Sherif again. Never cook for him or take a mug of tea from him. There was a buzz in her ears, a pressure. She tried to stay calm for her children’s sake but it was no good.

‘I came with your father to this country and now he has left me,’ she said and burst into tears. Sherif had sometimes talked of going back home. Suad had not believed this, but Sherif was keen. He had talked of being buried with his ancestors. Now, this dream was dashed forever. Suad would certainly not return on her own. Her future must be here.

Instead of eating with the children, she went to bed. The flat was split level. The bedrooms were in the basement and lead out to the garden. The kitchen and living room were on the ground floor, overlooking the street. Lying down, she could hear her children talking upstairs.

They were all exhausted and upset. Anything and everything could spark more tears. Suad and Mazen made the most noise when crying. Hamza was dry-eyed and Nesrine, after the initial hysterics, wept quietly.

It frustrated Suad that she could not ask Sherif his opinion. Would he have wanted her to do this or that? It hurt her head. Simple things confused her. She had forgotten to take her medication, but how many times? She needed to get back to everyone who had sent her messages. She would start to listen to her voicemails but then lose concentration. She tried to remember the last thing Sherif had said to her. It had been such an ordinary day. The evening before was ordinary too.

The next day when Suad woke up her head was clearer. There were practical matters to resolve. Paperwork. Insurance. The death certificate.

Strangely, Suad found herself competent, alert, able to deal with all these things. Thinking about them was a distraction from feeling her pain. Sherif’s car had been left at the school. It needed to be brought home. Where were his car keys? Where were all the things Sherif had with him – a Tupperware box with his lunch, his phone, his wallet? Had he died before finishing his lunch?

Three days passed, then five days, then a week, and the family began to settle. When one of them cried now, it was because of something new they saw. Nesrine came across photos of herself as a little girl in her father’s arms. Photos taken in playgrounds and the zoo. Tears ran down Hamza’s face when he collected his father’s car, the same one Sherif had taught Hamza to drive in. Mazen cried when he used his father’s phone charger because he had lost his own. Suad washed Sherif’s clothes that were still in the laundry basket. The shirts, underwear and pyjamas smelled strongly of him.

The manner of Sherif’s death troubled Suad. Suddenly, in the staff room. Sherif could have died in many other ways. Better ways. He could have died in his sleep, peacefully, right next to her, safe in their bed. He could have died in hospital, like most people do, after friends and the children had visited him to say goodbye. In hospital, Sherif would have appreciated the medical care he was getting. He would have compared his good surroundings to the dismal conditions people like him faced back home. He would have made these comparisons and he would have been grateful.

Even better than a hospital, Sherif could have died at the mosque, in the middle of prayers. This would have been a death to be proud of. This would have been proof that he was a good religious man, with his heart in the right place. Instead, he had died at work as if work was the most important part of his life. Sherif had been a good teacher but teaching maths had never been his dream job.

Sherif had trained as an architect before he came to Britain. For a long time, he said he was an architect even though he did not have the correct qualifications to work as one in Britain. Instead, he signed up for a local authorities’ scheme to train maths teachers. He was an ideal candidate. He did well and spent a lifetime teaching. Still, Suad did not believe that he had been passionate enough about his job to die at work.