11,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Salt

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

The Observer: Fiction to look out for in 2019 Exploring themes of ownership and abandonment, Eleanor Anstruther's debut is a fictionalised account of the true story of Enid Campbell (1892–1964), granddaughter of the 8th Duke of Argyll. Interweaving one significant day in 1964 with a decade during the interwar period, A Perfect Explanation gets to the heart of what it is to be bound by gender, heritage and tradition, to fight, to lose, to fight again. In a world of privilege, truth remains the same; there are no heroes and villains, only people misunderstood. Here, in the pages of this extraordinary book where the unspoken is conveyed with vivid simplicity, lies a story that will leave you reeling.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2019

Ähnliche

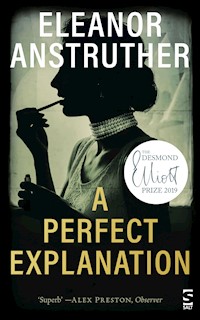

A PERFECT EXPLANATION

by

Eleanor Anstruther

SYNOPSIS

Observer: Fiction to look out for in 2019

The i Paper’s 30 of the best new debut novels to read in 2019

Exploring themes of ownership and abandonment, Eleanor Anstruther’s debut is a fictionalised account of the true story of Enid Campbell (1892–1964), granddaughter of the 8th Duke of Argyll.

Interweaving one significant day in 1964 with a decade during the interwar period, A Perfect Explanation gets to the heart of what it is to be bound by gender, heritage and tradition, to fight, to lose, to fight again. In a world of privilege, truth remains the same; there are no heroes and villains, only people misunderstood. Here, in the pages of this extraordinary book where the unspoken is conveyed with vivid simplicity, lies a story that will leave you reeling.

PRAISE FOR THIS BOOK

‘A riveting story about class and inheritance that explores how chance events can kick off a chain of consequences and seemingly minor decisions create catastrophes. It is exquisitely written – it reminded me of reading Elizabeth Taylor or Virginia Woolf. It is crammed with cruelties both big and small and yet Anstruther brings these finely crafted characters to life with both an unflinching eye for their faults and a compassion for those trying to survive in a society where love is rationed. I was utterly gripped – even more so because the story is based on true events. Take note folks, Eleanor Anstruther is the real deal.’ —Tor Udall

‘Gripping and beautifully written, this is a story about motherhood, privilege and women who simply won’t, or can’t, fit in. A brilliant read. I loved it.’ —Eve Chase

‘I read A Perfect Explanation almost between my fingers – such a haunting story, beautifully told, about an exceptional situation that somehow goes to the heart of the many truths, deceptions and lies recognisable in many families. One feels so sorry for each character in turn – Enid, Finetta, Ian, all victims of time, failings and circumstance. The clashes between motherhood, religion, class, gender and personalities are all the more affecting for being portrayed with clarity and fairness. Eleanor Anstruther has written a fascinating debut and an imaginative reconstruction of her own family history.’ —Amanda Craig

‘Although it’s not a happy read, the emotional intensity drives the reader on … and on. The journey of the beautiful socialite in the spotlight, to the sociopath in the shadows is compelling and will, I am sure, hit a nerve for many of the novel’s readers. An intense and thought-provoking read.’ —Essie Fox

‘What a task to take on – diving into the inner world of desperately flawed and broken people and still finding a way to elicit our sympathy. Such a brave, unflinching portrait of a family.’ —Matthew Tynan

‘Anstruther exhumes the skeleton in her family closet with devastating skill. A captivating, chilling, deeply insightful portrait of a family torn apart by responsibilities both taken on and pushed aside. ’ —Sam Bain

REVIEWS OF THIS BOOK

‘Eleanor Anstruther’s superb debut, A Perfect Explanation (Salt, March), the fictionalised story of the granddaughter of the eighth Duke of Argyll, who sold her son to her sister for £500.’ —Alex Preston, The Observer

A Perfect Explanation

Eleanor Anstruther was born in London, educated at Westminster and read History of Art at Manchester University. She lives in Surrey with her twin boys.

Published by Salt Publishing Ltd

12 Norwich Road, Cromer, Norfolk NR27 0AX

All rights reserved

Copyright © Eleanor Anstruther,2019

The right ofEleanor Anstrutherto be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by hwe in accordance with Section 77 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

This book is in copyright. Subject to statutory exception and to provisions of relevant collective licensing agreements, no reproduction of any part may take place without the written permission of Salt Publishing.

Salt Publishing 2019

Created by Salt Publishing Ltd

This book is sold subject to the conditions that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, re-sold, hired out,or otherwise circulated without the publisher’s prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

ISBN 978-1-78463-165-9 electronic

To Pardy

As Bad as a Mile

Watching the shied core

Striking the basket, skidding across the floor,

Shows less and less of luck, and more and more

Of failure spreading back up the arm

Earlier and earlier, the unraised hand calm,

The apple unbitten in the palm.

philip larkin

1

Finetta, 1964

What irritated Finettaabout her mother was not the lack of love but the obvious hatred. Lack of love was easy to explain – her mother had loved others more, her love was finite, there was only so much to go round. But her hatred was endless. Finetta had tried in myriad ways to understand it, but at forty-four, she was tired. It was inexplicable. She had to live with it.

For her own daughter she felt little either way. She neither loved nor hated her. She felt ambivalent towards her and the ways about her: her presence, how she did her hair or poured the tea. Her daughter was a stranger who moved with a stranger’s mood; a thing that passed and left little trace, unlike her son, for whom she felt a love so crushing she could only watch him, constantly, whether he was there or not. She wondered, sometimes, if it mattered; this black and white way of her heart – but what could she do? There was either feeling, or there wasn’t, and neither force – ambivalence nor adoration – had dissuaded her from duty. She’d fed and bathed them both, divorced their father and sent them away to school as soon as possible. They had grown up. Now she found herself back in the role for which she was made and in which she felt the least and most comfortable – that of looking after her mother. Her mother’s nursing home was in Hampstead. It looked pretty from the outside, a large red brick house on a quiet street, but the inside had been stripped of beauty – it had unfortunate lighting and a lift that didn’t work, Formica tables, single beds and nylon sheets. It was her mother’s just deserts.

She looked at the letter again while the kettle boiled. Coming Tuesday. No need to tell her, better not. I won’t stay long. Shall we lunch beforehand? Say 1pm, usual place? Ian

Better not to tell her for whom? Him? Her? Their mother? Obviously she’d had to tell the nurses – they liked to know the name of every visitor – but she’d made it clear. She’d made it absolutely clear that they weren’t to say a word until she got there. She’d be the one to say, Ian’s here. He’s come to see you. Not the nurses with their incontinent nonsense, spilling it out as though it were something thrilling. No. Finetta would be the one to tell her – perhaps she’d have to make him wait outside the door, but it would be her who’d do the spilling, with care and consideration and just enough distance to duck. Her mother might think her a bloody nuisance, but she wasn’t cruel or stupid. She knew what it all meant. She put the letter back in its envelope, propped it again on the shelf beside her notebook and got her cup and saucer from the cupboard.

Finetta was beautiful and tall. She had hooded blue eyes like a sculptor’s Nemesis set in an angular face framed by thick dark hair that waved gently without curlers. She’d cut it to shoulder length and wore it clipped back like a schoolgirl. She was thin, as her mother was, with elegant hands that drew attention from her face when men were desperate to look somewhere else. She wore no rings – her failed marriage was discarded in the bottom drawer of her bureau.

The kettle boiled, the pot already warmed on the Rayburn. While the tea steeped she sat at her kitchen table, a quilt on her lap, and opened the sewing box. It was to have been a Christmas present for her mother but she’d almost finished it. One more patch to go. She could finish it this morning and give it to her this afternoon. It was probably better not to wait for such dates as Christmas or birthdays anymore – in the face of her mother’s deterioration they had become arbitrary. Who knew if she’d live till then? It was better to finish the patch now and give it to her before death crept any closer.

It was pretty enough, pieces cut from old dresses and curtains, backed on to undyed linen. Her mother would hate it but the nurses would think her ungrateful and keep putting it back on her bed. It gave Finetta joy to think of the confusion, the kind prison her mother was in. She rearranged the quilt to stop it slipping from her knee.

Starting something was easy, she thought as she adjusted a pin. It was the starting that was the joy when no mistakes had been made, when the world was free and open, when nothing was said that needed to be unsaid and there were no bad stitches. If life were nothing but beginnings with something else taking over the difficult middle and horrid end, how much simpler it would be. How much happier. People were not designed to change – God had not thought it through. They broke down instead, but what did God know? He who had made such a hash of it all. God was a trick made up by people too frightened to think of anything else. She spread the quilt over the table. It would do. Most of the mistakes were hidden under calico.

She poured her tea and arranged herself again at the kitchen table, the quilt on her knee. Her needle travelled back and forth through the patch of red silk dotted with white flowers and she kept her eyes upon it. She was used to the sharp sting of a misdirected point and though she’d done it – made patchworks, darned socks, mended skirts – a thousand times before, she still got pricked occasionally and it still stung.

She stopped for a moment, drank some tea and sniffed. Winter. What a bore. Freezing nights and her mother still not complaining. If only she would act normally, like all the others who crowded into that dreadful place, getting meat jammed in their teeth and holding hot water bottles to their stomachs, wiping their streaming eyes with the backs of their painful hands and chivvying each other along. But her mother refused to be drawn. She was silent, focused, upright except to turn slow watery eyes upon her daughter, fail to smile and look away. She never asked her how she was, never said thank you when Finetta drove halfway into town to fetch her new stockings, never said thank you at all.

With her ankles crossed, a cashmere thrown over her shoulders, an electric fire pulled to the middle of the kitchen floor emitting a three-bar heat, Finetta looked like a flower grown used to growing in the dark. Precision, that’s what she cared about, a commanding order that gave her life outline. Tea before toast, a quilt before death, an annual lunch with her brother. She turned it over, tied the thread and snapped it with her teeth. The last patch was from a blanket the moths had got to. She hadn’t liked it. It had reminded her of poverty.

The Rayburn poured slow heat over clean tiles, empty surfaces, polished sink. The cupboards, worktops and floor were all varying shades of tan. Tan, she’d discovered, was an easy colour to make look clean. She took a half-loaf of bread from the bread tin, a board from behind the sink, a knife from the drawer, and cut a slice. Tea, toast, precision, quilts, her mother, and occasionally she made fudge in the afternoon when she’d nothing better to do – she had tins of the stuff, she couldn’t keep up – but these things kept her occupied. As a child she’d had her bird book.

It had been easier then – her thoughts had not developed the ragged edges they had now, the subtle insistence that there was more to realise if only she’d follow them up. When she was a child they had been single, isolated cut-outs which had been easily replaced with a picture of a robin. Now she had to look away sharply to avoid seeing what her thoughts dragged with them. But she was strong. She would not be drawn. It did no one any good.

She stood at the worktop and buttered her toast. Surely she was too old to feel angry. She wished the sensations would go away. There was no need for them, and it was rude of them, in her quiet kitchen, to think they could intrude when she was supposed to be getting dressed and getting ready for a normal day that had just one little bump in it. They had begun to intrude more and more, edging in until it seemed normal to see them inside the door, sitting on the kitchen floor, crouched at the foot of her chair. Soon they’d find their way into her bedroom. Then she’d have to take a sleeping draught to keep them away.

She’d spent her life believing things could be compartmentalised, kept apart by scissors and sticky tape, labelled and stuck down with no risk of one image sneaking over to another. She’d had her mother page, where she’d been Neat, Solemn, Quiet to the point of Piousness. On her aunt’s page were Good Manners, Amusing Chatter and Gossip. With her father she was Pretty and Happy; with her brother, Un-minding and Stoic – it had all worked surprisingly well until she’d grown up and left home. But as an adult, the overlay of romances, children and divorce had smudged the cut outs and she’d returned to the pages to find they had bled one into another. Who could she be to her brother now? Why did Neat no longer work with her mother? It was as if survival was a debt she must repay by ghastly examination. She didn’t want to peel the images apart. She didn’t want to look. She should tell her mother to stuff it, but was over-ruled by a small girl in pig tails with a bird book trying to pour tea without spillage. What about loyalty? Yet she returned, week after week to attend to that disappearing life as if it had offered her warmth. Her brother said she was a fool, yet the older she got, the younger she became. She’d got along perfectly well for forty-four years refusing to be affected by anything. Why start now? But, like everything else in the childhood that crept upon her, it felt beyond her control.

She rubbed her chest with the heel of her hand. She wanted to put the contents in the sink with her cup, wash them up, pour them away. Of course she couldn’t. She had to clench her jaw, go upstairs and get dressed. She kept a firm grip on the knife as she ran the blade under hot water.

In the bathroom, she inspected her face. It will do, she thought, touching her lips with the tips of her fingers. She always thought that as she moved away from her reflection. It will do. She knew she’d been beautiful, as if it were a fact stored in a book at the London Library. Everyone said it and men, well, they’d ogled her, but what she saw was pointed and sharp. She saw her mother’s eyes and her mother’s mouth and wished she didn’t.

As she ran her bath she thought she heard the telephone ringing. She turned off the taps and opened the bathroom door, but the house was as still and as quiet as ever. Nothing. She shut the door and turned on the taps again. She undressed, laying her cashmere over the back of the bathroom chair and her nightgown folded neatly on the seat. Gratefully, she stepped into the deep, warm water. Thank goodness the boiler had been mended. The water was piping. But just as she dropped her head back and let the water slop over her, the phone started ringing again.

Goddamn it, she thought, sloshing her legs and getting out. She wrapped a towel around her and padded downstairs, shoulders wet, the tips of her hair dripping.

2

Enid, 1964

From her chairby the window, Enid stared at the trees which bowed and swayed and threatened to dislodge the pigeons that clung there. Her reflection was ghost-like in the glass. The light picked out her crinkled skin, the sag of her cheeks, how thin her mouth had become. Her hands, folded in her lap, conveyed the essence of her bones; gnarled with a tremor that mislaid things.

She was trying not to think of her sister. She was trying very hard indeed. She’d mostly erased her, she’d almost got rid of her completely, but this morning, up she’d come, resurfacing like so much flotsam, as present as if she were in the room – the living, breathing Joan who perhaps still lived and breathed somewhere. Enid could almost smell the trail of Turkish tobacco, the slick of gin and hint of eau de lavender, could almost see the defiant bones that broadened that face, the globe eyes, the heavy lids open on blue islands with black at their heart. One of these days it wouldn’t just be memories, it would be her in spirit, come to say sorry.

But today it was memories, and although she closed her eyes and opened them again, though she stared at the trees and counted the pigeons and made a bet with herself over which would fly off first, her sister reared before it all, blotting out everything like the ghost that she couldn’t get rid of.

Her fingers played over a ring on her left hand; an emerald set amongst diamonds on a band of deep gold. Ageless and prominent as if washed up on driftwood, the jewels glinted above skin that had lost its fat and become the colour of mud-spattered sand. Once upon a time, even after Joan had got the knives out, Enid was young and beautiful; always more beautiful and younger than Joan, and perhaps that was the shallowest of causes. Just that. She even had a portrait by Augustus John to prove it – her head half-turned, her hand in mid gesture as if she were saying something. She had been, though she couldn’t remember what. It had moved with her, from one corridor wall to another and finally to here, a bedside cupboard in Hawthorne Christian Science House.

She pushed her thumbs against the top bones of her eye sockets, making her forehead ache. She wished she could stop thinking of her. Like the television downstairs that fired pictures of American soldiers into the shabby lounge of the nursing home, Joan transformed a tired plain into a place of war. The anger that slept and the grief that haunted woke up and shouted, the hurt showed itself undimmed and Enid’s thoughts became furies, a battlefield overrun with blood and trenches. On days like these it was impossible to traverse from one side of her mind to the other without falling in a hole, tripping on a jagged bone or snagging her skirts on barbed wire; her very own Vietnam or Gallipoli, alive with a carnage she couldn’t stop.

There was a knock on her door.

“Enid?” It was Carol, one of the nurses. Fat Carol with the piggy eyes, come to brush her hair and clean her up, ready for her weekly visit from Finetta.

Her daughter always came on a Tuesday, and she was very particular about Enid’s care, noticing the smallest things, like a ladder in her stockings or whether her nails had been done. Enid didn’t know why she bothered. If it was inheritance she was after, there was none; Finetta should be the first person to know that. Enid played with the ring, moving it with slow, unconscious rhythm over her knuckle. There was nothing Finetta could possibly want that she wasn’t going to get anyway: a wardrobe of tattered clothes, a few stoles lying about, a bit of jewellery, the Augustus John. She couldn’t think that any of it was worth anything, apart from the ring. Enid pushed it down her finger again, back into its place, and tapped the emerald. She couldn’t bear assumption. She had half a mind to be buried with it. But what on earth more did Finetta hope to gain? Some emblem of a parent, just because everyone else seemed to have one? Enid had done nothing to deserve such loyalty and she resented it. She wanted to be left alone. She didn’t want to have it pointed out that she was still a mother. It was as if Finetta did it on purpose, shoving the reminder of her existence as a punishment from which Enid could not escape, a revenge dripped week by week, never letting the grass grow, making Enid re-tread the paths with every Tuesday view of her bloodline.

Enid brushed down her skirt and tried to see her mouth in the window. She scratched at each corner, her lips in an O, and then pressed them together as if she wore lipstick. She didn’t. What would be the point? Finetta was still such a beauty she hadn’t considered the possibility of her own lips growing thin. Or perhaps she had. A failed marriage, a son she doted on, a daughter she occasionally spoke of – the haunting of another generation. What did it matter if Enid’s stockings were laddered? Who was going to see? Finetta had been like that since a little girl, particular about the slightest detail of her own dress or nails, her manners, her composure in the face of turmoil. Perhaps she was making up for the fact that until she grew up and left home, with that silent, breath-taking beauty of her own, no one had taken any notice of her at all.

Carol finished straightening the bed. “Have you had enough breakfast?” She picked up the tray of untouched porridge, the half-piece of toast, the empty tea cup and stainless steel pot.

“Enough,” said Enid, her hand loosely in the air. It was too late for vanity now. Everyone in this nursing home was waiting to die and doing nothing about it.

Carol carried the tray to the door and put it on the trolley that she’d parked in the corridor. She came back in, closed the door behind her and walked heavily over to Enid. She placed her plump hand on Enid’s shoulder.

“A little comb through, shall we?” Carol’s cheeks were so large that when she smiled her face creased into an undulating mass and her pig eyes nearly disappeared completely. Joan had been fat too. Not as fat as Carol, but large enough to make every item of clothing look as if it were screaming. Last time she saw her, she’d been squeezed into a blue suit and squashed onto a bench in court, Pat clinging to her side. Lesbians. Enid would have used the word if she’d thought she’d have been believed, but she knew, she’d known then, that their mother would have deployed her favourite weapon of looking the other way.

She felt Carol’s hand drop from her shoulder. In the reflection of the window she watched her fetch a comb from the sink and felt it softly tug through her hair. Enid tilted her head and rested it in Carol’s hands, lifting her gaze to the pattern of the trees outside – limbs bare against a pallid grey – and then higher still to the edge of the window and the ceiling above her, white-painted and empty but for the strip light, flickering on low. Carol said, “Keep still,” and untangled a knot.

She hadn’t reckoned on being reminded, when it was all too late, that everything they’d done was based on grief.

“Perhaps you’d like to change into something clean?” said Carol.

I’ll pay you £500 if you give him up. But she hadn’t known that Joan meant: and never see him again. If she had known, no money on earth would have been worth it.

“I could look out your blue one with the collar.”

Twenty-five years ago. He’d be in his forties by now.

“Enid?” Carol touched her arm.

Enid felt the light press on her sleeve but all she could see was her son in the back of her sister’s Rolls Royce as it eased slowly down the narrow street, paused briefly at the end, turned left and accelerated out of sight. She’d pretended, for a while, that he’d come and see her. It had eased her mind. There’d been no reason why he shouldn’t; she was still his mother. She gripped the arm of her chair. If Joan had been forced through the imprisonment of marriage and brutality of childbirth, perhaps she’d have done the same, but she hadn’t and so how foolish to think she’d have understood.

“Enid?” Carol gently shook her arm, her face close. “Everything all right?”

“What?” Enid’s voice was cracked from under-use.

“I asked if you wanted to change into something clean. You’ve been in that since Saturday.”

“Oh. Yes, I suppose so.”

“It’s time we put that one in the wash.” She held out her hand for Enid to stand up.

“Can’t you do it later?” She couldn’t just now, she was too tired.

Carol put the comb on the sink. Enid stared out of the window. Twenty-five years and nothing. Not a visit, a phone call, a note. His father had died, and of course she hadn’t gone to the funeral – it would have been improper. There was no knowing who might have been there. Joan would have been there. A grave was no place for a reunion and anyway, she’d heard of it too late. She could have gone to her mother’s funeral, she supposed. Ian would have been there, too. She’d wavered over that one. Despite everything, it would have been perfectly correct. That galleon ship, that empress of duty had done what mothers the world over did when an heir was lost – she’d drifted and grown old, become suggestible and weary of the load. But Joan would have been there too, slipping into their mother’s shoes, and Finetta had talked Enid out of it. She’d said Scotland was a long way to go.

“You’ll want something nice, won’t you?” said Carol. She stood behind Enid, her hands lightly touching her shoulders.

Enid stared at her reflection. Their mother wouldn’t have wanted her at her graveside anyway. She would have seen it as an offence, and Joan would have agreed absolutely. They’d been an army of two, allied in everything, and the thought of being shamed again, even after their mother was dead, had been too much. As she’d expected, no letter from the executors had arrived, no summons to hear the Will. Nothing but an aside from Finetta: that the funeral had been quite pleasant, although it had rained.

Carol patted a stray strand of Enid’s hair into place. “I’ll get you the mirror.”

She’d had no one to fight for her, that was the thing. No one to hold her hand, talk her round or give her reason to think sensibly. Ian’s father had cowered and done as he was told. He’d had no reason to defend her, but was there no such thing as compassion? The men she’d loved were dead – her brother, her father. Sometimes she was grateful that her father hadn’t lived to see his family fall apart. Her mother had told her once that it was Enid’s marriage that had killed him. Some words, once uttered, could never be forgiven.

Carol held the mirror up for Enid to turn her head from side to side and admire what little was left. “All right?” She put it into Enid’s hand and went to the cupboard. There was a jangle of metal hangers as the blue dress with the scalloped collar was removed. “I’ll give it a quick iron.”

Enid laid the mirror in her lap.

“Anything else you need?” Carol was beside her, the blue dress over her arm. She reached for her stick and took Carol’s hand. No, she’d had no one. No one had held her in their arms and said, I understand. You’ve been under a terrible strain. You mustn’t worry. I’ll take care of you. Everything’s going to be all right. No one had been there for her when she’d needed help. It was no wonder she’d panicked.

Carol led her into the middle of the room. “Do you want to sit somewhere else?”

She wasn’t at all sure why she’d stood up. “I’ll sit here.” She pointed at the easy chair by the unlit grate.

Carol patted her on the shoulder. “I’ll be off, then. I’ll get this back in a jiff.” She was smiling like a clown, a fool with something to say, tight-lipped and squeezed. “We’ll be expecting your Finetta here at four as usual.” She patted her shoulder again. “I shouldn’t tell you.”

Enid felt irritation rise through her veins. Carol was always making a nonsense of life, as if it was fun. “Tell me what?”

“Only Mandy thought you might like to know, seeing as it might be a shock.” She bent towards her.

“Tell me what?” she said again, easing into the chair.

“She said last week not to say until she was here. But I can’t see it matters, and we wouldn’t want you to feel we hadn’t thought. I never knew you had a son.”

Enid looked up at her. “A what?”

“Ian.” She raised her voice and leant close, a great, planet face in a universe of ignorance. “Is that right? I expect he’s as handsome as Finetta.” She straightened up. “I’ll bring tea up with them, shall I? They’ll be here at four sharp.”

Enid tried to push herself out of her seat but got only as far as a slight lift before falling back. Her stick, hooked precariously over the armrest, fell to the floor. “Ian?”

Carol swapped the dress to her other arm and picked up the stick. “That’s what she said.”

“You mean Michael?” She must mean Finetta’s son. Stupid woman must have got confused.

“No.” She hooked it over the armrest. “Ian. She wanted it to be a surprise, but I thought, well we thought—”

Enid balled her hand into a fist, it jerked against the stick sending it flying once more. Her heart smashed against her ribs – seeing him in the Rolls, watching him not turn around, twenty-five years of silence. “You’re certain?”

Carol picked it up again. “That’s what she said.”

This was what Joan used to do. “She’s doing it on purpose.” An uncommon sweat sprang over the dry parchment of her back, and her temples pressed in on her brain.

“Who’s doing what on purpose?” Carol’s fat face was too close again.

“Finetta.” Enid turned her head the other way. “Hurting me.”

Carol hooked her hand under Enid’s elbow. “Why don’t you lie down for a bit? I could get you a nice drink of milk.”

“I don’t want milk,” she snapped, pulling her arm free. “My stick.”

Carol put it in her hands. “Where do you want to go?”

“I need to telephone.”

“She already said she’ll bring the shortbread.”

“Shortbread?” She tried to stand but she wasn’t getting anywhere. She grabbed Carol’s wrist.

“Has he been abroad?” Carol put her other hand on Enid’s and helped her up. Enid shoved her stick out in front of her and took a step. “Why is he coming?”

“I expect he wants to see you,” said Carol, gently.

“But I don’t have any sons.”

Carol let out a puff of breath. “Well I’m sure I don’t know. Why don’t you let me telephone?” She halted on the carpet, halfway across the room, the dress shoved into the crease of her elbow. “You don’t have any sons?”

“You must tell her I’m not well.” Enid marched another step across the room.

Carol took a sudden left turn and steered Enid towards the bed. “There’s no need for you to come all the way to the office. I’ll be done with my rounds in a tick and then I’ll do it. Have a lie down ’till lunch. I’ll come and get you.”

“I don’t want to lie down.” They treated patients like imbeciles, as if upset could be cured by raised feet, but like a toy released, Enid found herself propelled towards the bed, unable to halt and turn, a victim of the rush of her brain, her very own Gallipoli, alive with a carnage she couldn’t stop.

“Tell her I’m not feeling well today.” She reached the bed. Her hands touched the counterpane.

“Of course you’re not. I can see that. I’ll come back and check on you in half an hour,” said Carol. She whipped across the room and shut the door behind her.

3

Enid, 1964

The room, largebut plain, had a cornice which disappeared into a modern partition that cut what was once grand into a half-cocked idea of practical comfort. In the lottery of room divisions, Enid’s had won the fireplace. Around it were two armchairs and a coffee table, and from her bed their emptiness felt like a warning. She lay on her back, as if she were dead, and stared at the ceiling, her arms crossed over her chest. She hadn’t spent twenty-five years designing a perfect explanation for her life only to have it shot down in one surprise attack. It wasn’t on. She wasn’t prepared for it.

She eased off her shoes and flexed her toes. Three on each foot responded. The others, fused in a united dispassionate nod, had given up on independence years ago – they didn’t care to join in, they made no effort. She twisted each ankle. They were bony, like misshapen sticks. It was unacceptable. Who’d stolen her life? That’s what she wanted to know. It was hers that needed answers. She’d given up her sons’ lives long ago. She’d lost them both. If a man insisted on calling himself such, the correct course would be to write. Why hadn’t he written? He’d had decades to compose a note that need only say, Mother—.

Her ankle joints creaked and popped. She wanted to break them. Snap, they’d go. Then she wouldn’t be able to walk. They’d have to call for an ambulance, despite themselves and their stupid rules. For fifty years she’d lived by them. Fifty years of Mary Baker Eddy and Christian bloody Science. No medicine, ill health a result of a sin that can only be prayed away. Try praying this away, she thought, and then shut her mind. If she broke her ankles they’d have to send her to hospital because she’d be screaming.

She bent one knee and then the other. Agony. That was the word for them. They failed her with bitterness and revenge. What had she done to deserve this? She’d asked them only to perform the duty for which they were made. She hadn’t tortured them or pushed them beyond reasonable endurance. Bend and straighten. Support her weight. Was that too much to ask? Yet they swelled and tore, they ground against the bone, they gave in sudden, jerking shatters that left her frightened of stairs.

Her eyes wept without emotion – they watered regardless of her mood. She reached for a tissue from the box on her bedside table.

If his brother had been perfect there’d have been no need for him. She’d said it then and she said it now. Forty-two years ago, she’d sat in the window seat of Cherry Trees, a clean dress on, her hair brushed for the first time in days. She’d stared at her new-born son while nanny held Finetta, and cried helplessly while her mother clapped her hands and looked the other way, while Douglas looked embarrassed.

Her heart spasmed, and she had to clutch her chest. He couldn’t come. It was unacceptable. He couldn’t just turn up as if he’d seen her yesterday and expect everything to have been kept on ice for him, as if she’d died when he’d left and could only be woken by his forgiveness. As if he had a right to stand in judgement. He didn’t know. He’d been too young to understand.

She dug her hands into her hips – bony and collapsed, no hint of the widening softness that had made way for children. Giving birth had ruined them. There. She’d said it. Try me, she thought, as if staring a bull in the face. Just see if I can’t think of those episodes of carnage. But her chest spasmed again and she had to open her mouth to breathe. She tried lying on her side but it didn’t help. She might get it into her head to cry and she hadn’t done that since he was born.

She sat up slowly and swung her feet to the floor, took her stick from where it hooked over the plastic rail of her bedstead and walked slowly across the room.

On the white walls of the corridor hung cheap prints of generic vistas: a seascape, a landscape; places no one had been. The floor was carpeted in green. To her left, the corridor ended in another room. To her right, it twisted out of sight down a small flight of stairs. She approached the first step, grabbed the wooden handrail and lowered her foot. Her knee gave quickly and she was thrown forward, but the other foot came spinning out to her rescue and caught her light weight. She stood for a minute on the second step, breathless. Her hand shook like her mother’s used to; a bell that wouldn’t stop ringing.

A draught whistled along, catching her at shin height. She lowered herself onto the next step until she was sitting down, one hand still holding the rail, her knees hunched together. It felt like the turn in the stairs down from the nursery at Strachur. She hadn’t been back to her mother’s house in Scotland since the whole terrible mess began. Crouched, knees bent, she could be twenty-eight again, halfway down the first flight, not daring to go further, not daring to go back. I can’t see. Those had been his first words after the blood had stopped pouring and they’d bandaged him up. She’d wanted to smother him.

She wouldn’t be accused. With one hand, she pulled herself onto her feet, her stick in the other, leant against the wall and looked around the corner. The door at the far end opened and one of the nurses came smiling out, throwing a comment behind her. She didn’t notice Enid peeking around the bend. The nurse disappeared off down another flight of stairs. On the next step, the handrail swapped to the other wall. Enid made a grab for it.

Why had she chosen to be a Christian Scientist? Why not a Humanist or a Pantheist, or a Presbyterian like her mother? She could have lain down on that foul green carpet and refused to move; she could have said her heart was breaking. They would have had to call a doctor. They could have taken her away from here. But she hadn’t chosen it. She remembered now. It had chosen her.

She walked slowly along the passage to the office.