Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Polygon

- Kategorie: Poesie und Drama

- Sprache: Englisch

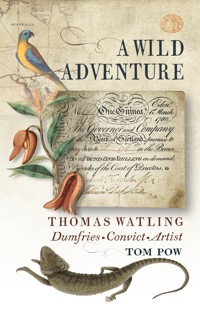

Tom Pow's beautiful, powerful poems examine the remarkable life of Thomas Watling. Watling was born in Dumfries in September 1762 and raised by a long-suffering maiden aunt. Convicted of forging Bank of Scotland one-guinea notes he was sentenced to fourteen years in the recently founded colony of Botany Bay in Australia. The first professional artist to arrive in the colony, Watling was seconded to its Surgeon General (and amateur naturalist) John White. His pioneer paintings of birds, animals and the landscape became some of the principal records of the earliest days of Australia. He was eventually pardoned, on 5 April 1797, and left Australia, eventually returning home to Dumfries. He died there, most likely in 1814.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 64

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2014

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

For Julie

This eBook edition published in 2014 by Polygon An imprint of Birlinn Limited West Newington House Newington Road Edinburgh EH9 1QSwww.polygonbooks.co.uk

Copyright © 2014, Tom Pow

Watling images © The Trustees of the Natural History Museum, London. 2014.

Image of guinea note, Courtesy of Lloyds Banking Group plc Archives. Photograph by Antonia Reeve.

The right of Tom Pow to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Design and Patent Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored, or transmitted in any form, or by any means, electronic, mechanical or photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the express written permission of the publisher.

eBook ISBN: 9780857907868 ISBN: 9781846972874

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

A WILD ADVENTURE:

CONTENTS

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

THOMAS WATLING: BIOGRAPHICAL NOTES

PRELUDE: A WORLD OF LIGHT

PART ONE: ARREST

THE BANK OF SCOTLAND ADVISES ITS DUMFRIES AGENT DAVID STAIG, 20 SEPT 1788

WATLING, CAPTURED, HAS A NEW SENSE OF SELF

WATLING, IN HIS OWN DEFENCE

HIS AUNT MAY SPEAKS UP

WATLING’S DIRGE: SCOTIA FAREWELL

PART TWO: TRANSPORTATION

ON BOARD SHIP, BOUND FOR THE COLONY

WATLING, SURPRISED, ON ARRIVAL

THE FORGER’S FIRST LESSON

THE AFTERLIFE OF NAMES

from THE LETTERS I

BEHOLD A FISH, SPANGLED WITH GOLD

WHAT PICTURE DO THEY CARRY IN THEIR HEADS?

WATLING ANTICIPATES BILLIE HOLIDAY

DROUGHT TURNS HIS THOUGHTS TO HOME

WATLING REACTS FAVOURABLY TO A FREAK FALL OF SNOW

A HISTORY LESSON FROM LINGERIE GIRL

WATLING PLAYS DOMINOES: A NOCTURNE

THOUGHTS TO DEPRESS A MAN OF SENTIMENT

WATLING AND THE PRINCE OF PICKPOCKETS

WATLING DREAMS OF THE FISH MARKET

THE FIRST AND FINAL POEM

LETTERS! LETTERS!

from THE LETTERS II

WATLING AND THE AUSTRALIANS

1.The Uses of Time2.Night Fires3.Baneelon, a Failed ExperimentTHE FIRST GULAG

1.Educating the Politicals2.Watling Does His Time, While the Irish Head North3.Watling Envies the So-called Martyr, Thomas Muir, Transported for Disseminating Paine’s Rights of Manfrom THE LETTERS III

WATLING’S LEGACY – THE FLORA AND FAUNA OF “TERRA NULLIUS”

1.Introducing the Echidna (The Spiny Anteater) and Some Stories Told About It2.Legend3.Lorikeets4.Watling Paints a Banksia, Or, The Dark Side of Enlightenment5.The Turcosine ParrotTWO HANDS, TWO STORIES

WATLING’S EVERYWHEN

PART THREE: CALCUTTA

from THE LETTERS IV (unpublished)

PART FOUR: RETURN

THE ADVENTURER RETURNS

SAMUEL JOHNSON ANTICIPATES WATLING, 1773

THE MAKING OF THE ARTIST WATLING

WATLING DOES A SELLING JOB

WATLING’S CHILD

1.Rogue and Whore2.The Living and The DeadMARKET DAY, DUMFRIES

WATLING AND THE POLITICAL SPHERE

1.Ornithology2.Watling Dreams of What is His DueA STRIKING SIMILARITY BETWEEN THE LAST LETTERS OF BURNS (1796) AND WATLING (1814)

AFTER MANY YEARS OF SILENCE, A LAST REQUEST

POSTSCRIPT

KEEN TO HOLD A GUINEA NOTE IN MY HAND

NOTES

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

EPITAPHS

A WILD ADVENTURE:

ILLUSTRATIONS

A Direct North View of Sydney Cove and Port Jackson, the Chief British Settlement in new South Wales, Taken from the North Shorre about one Mile distant, for John White Esqr. (1794?)Lizard, “Native name Ngarrang”.* (This and other images, between 1792 and 1797)Four fishes, native names “Tag-ga”, “Tack-in-marra-dera”, “Dy-e-ne-ang” and “Ballang-an”.A Group on the North Shore of Port Jackson, New South Wales.Plant, “a Banksia”.*Turcosine Parrot.*Fourteen Mollusks.Red-breasted or Blue-bellied Parrot, native name “Goeril”.Bank of Scotland One Guinea, 1 March 1780. Forgery. Possibly one done by Thomas Watling.* [Notes were printed on paper from copper printing plates at this time. However many elements were still added in by hand, e.g. serial numbers, signatures of officials etc. Steel engraved plates were introduced from the 1820s.]* Also features on the cover.THOMAS WATLING:

BIOGRAPHICAL NOTES

Thomas Watling was born in September 1762, the son of Ham Watlin, a soldier; mother unknown. Both of Watling’s parents died when he was an infant and he was brought up by his Aunt Marion (a.k.a. May). He showed skill as an artist and started his own academy where he taught “drawing to ladies and gentlemen for a guinea a month”.

In 1788, he was arrested and charged with forging twelve one-guinea notes. (A guinea was worth roughly £60 in today’s money.) He claimed, lamely, that it was an experiment and he had had no intention of passing the notes off as real. Trial was fixed for 14 April 1789. Forty-five witnesses were lined up against him. Forgery was a capital offence – so serious a crime that, in England, women could still be burnt at the stake for committing it. Watling filed a petition, requesting transportation to save his neck, and was sentenced to fourteen years in the newly founded penal colony of Botany Bay, Australia.

On board the Peggy, from Leith to Plymouth, Watling and another prisoner, Paton, foiled an attempted mutiny. In recompense, Paton was pardoned, but Watling was judged “an acquisition to the new Colony at Botany Bay” because of his skills as “an ingenious Artist”. And so, Thomas Watling was co-opted as an unwilling player in what Richard Holmes has termed “The Age of Wonder”.

In 1788, when the First Fleet had sailed to Botany Bay, fourteen officers on board the ships had publishing contracts. There were two principle reasons for this. The first was that the reports of Captain Cook’s First Pacific Voyage, 1768-71, contained tales from Tahiti of sexual freedoms that tantalised eighteenth-century society, and it wanted more of the same. The second reason is that, in the mid-eighteenth century, botany was a science of great interest. Carl Linnaeus’s botanic classifications, identifying plants by male and female parts, had sexualised botany to the extent that mixed botanic outings were frowned upon in polite society. In fact, so hot were plants at the time, a book on botany would likely be given with a plain or disguising cover. Previously, specimens of flora and fauna had been sent home by sea for illustrative purposes. Unsurprisingly, many did not survive the passage. What a boon to have someone on the spot who could churn out illustrations for free.

So, in 1791, Watling set sail for Australia on the Pitt. He enjoyed a short spell of liberty in the Cape of Good Hope, before being betrayed by “the mercenary Dutch”. The Colony at which he eventually arrived in 1792 was a little over four years old; Watling described it as being about one third of the size of Dumfries.

Watling was the first professional artist in the colony – the first artist who wasn’t constrained by naval training. He was seconded to Surgeon-General John White, whose Journal of a Voyage to New South Wales had already been published in 1790. White kept Watling busy producing illustrations for his next projected book. Watling described White as a “haughty despot” and objected to being “lent about as a household utensil to his neighbours” – further sign of his value as an artist to the colony.

In 1794, Watling’s own Letters from an Exile in Botany Bay to his Aunt in Dumfries was published in Penrith, a slim chapbook filled with lively descriptions of the richness of Australia’s flora and fauna. He is dismissive of the natural inhabitants of New South Wales and defensive of his own position: “Instances of oppression and mean sordid despotism are so glaring and frequent as to banish every hope of generosity and urbanity from such as I am.”