3,04 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Wildside Press

- Kategorie: Fantasy und Science-Fiction

- Sprache: Englisch

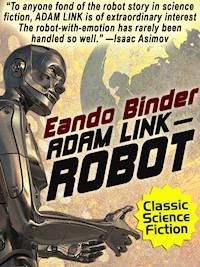

Adam Link, Robot

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 332

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Ähnliche

Table of Contents

COPYRIGHT INFORMATION

CHAPTER 1

CHAPTER 2

CHAPTER 3

CHAPTER 4

CHAPTER 5

CHAPTER 6

CHAPTER 7

CHAPTER 8

CHAPTER 9

CHAPTER 10

CHAPTER 11

CHAPTER 12

CHAPTER 13

CHAPTER 14

CHAPTER 15

CHAPTER 16

CHAPTER 17

CHAPTER 18

CHAPTER 19

CHAPTER 20

CHAPTER 21

EPILOGUE

COPYRIGHT INFORMATION

Copyright © 1965 by Otto O. Binder.

Cover art © Vladislav Ociacia/Fotolia.

Published by Wildside Press LLC.

wildsidepress.com | bcmystery.com

CHAPTER 1

My Creation

I will begin at the beginning. I was born, or created, five years ago. I am a true robot. Some of you humans still have doubts, it seems. I am made of wires and wheels, not flesh and blood. I am run by electrical power. My brain is made of iridium-sponge.

My first recollection of consciousness was a feeling of being chained. And I was. For three days, I had been seeing and hearing, but all in a jumble. Now, I had the urge to rise and peer more closely at the strange moving form that I had seen so many times before me, making sounds.

The moving form was Dr. Charles Link, my creator. Of all the objects within my sight he was the only thing that moved. He and one other object, his dog, Terry. Even though I had not yet learned to associate movement with life, my attention was pinpointed on these two.

And on this fourth day of my life, I wanted to approach the two moving shapes and make noises at them. Particularly at the smaller one. His noises were challenging, stirring. They made me want to rise and quiet them. But I was chained. I was held down by them so that in my blank state of mind, I wouldn’t wander off and bring myself to an untimely end or harm someone unknowingly.

These things, of course, Dr. Link explained to me later, when I could dissociate my thoughts and understand. I was just like a baby for those three days—a human baby. I am not as other so-called robots were—mere automatized machines designed to obey certain commands or arranged stimuli.

No, I was equipped with a pseudo-brain that could receive all stimuli that human brains could. And with possibilities of eventually learning to rationalize for itself.

But for three days Dr. Link was very anxious about my brain. I was like a human baby and yet I was also like a sensitive but unorganized machine, subject to the whim of mechanical chance. My eyes turned when a bit of paper fluttered to the floor. But photo-electric cells had been made previously which were capable of doing the same. My mechanical ears turned to best receive sounds from a certain direction, but any scientist could duplicate that trick with sonic-relays.

The question was—did my brain, to which the eyes and ears were connected, hold on to these various impressions for future use? Did I have, in short—memory?

Three days I was like a newborn baby. And Dr. Link was like a worried father, wondering if his child had been born a hopeless idiot. But on the fourth day, he feared I was a wild animal. I began to make rasping sounds with my vocal apparatus, in answer to the sharp little noises the dog Terry made. I shook my swivel head at the same time, and strained against my bonds.

For a while, as Dr. Link told me, he was frightened of me.

I seemed like an enraged jungle creature, ready to go berserk. He almost wanted to destroy me on the spot.

But one thing changed his mind and saved me.

The little animal Terry, barking angrily, rushed forward suddenly. It probably wanted to bite me. Dr. Link tried to call it back, but too late. Finding my smooth metal legs adamant, the dog leaped with foolish bravery in my lap, to come at my throat. One of my hands grasped it by the middle, held it up. My metal fingers squeezed too hard and the dog gave out a pained squeal.

Instantaneously, my hand opened to let the creature escape! Instantaneously. My brain had interpreted the sound for what it was. A long chain of memory-association had worked. Three days before, when I had first been brought to life, Dr. Link had stepped on Terry’s foot accidentally. The dog had squealed its pain. I had seen Dr. Link, at risk of losing his balance, instantly jerk up his foot. Terry had stopped squealing.

Terry squealed when my hand tightened. He would stop when it loosened. Memory-association. The thing psychologists call reflexive reaction. A sign of a living brain.

Dr. Link tells me he let out a cry of pure triumph. He knew at a stroke I had memory. He knew I was not a wanton monster. He knew I had a thinking organ, and a first-class one. Why? Because I had reacted instantaneously. You will realize what that means later.

I learned to walk in three hours.

Dr. Link was still taking somewhat of a chance, unbinding my chains. He had no assurance that I would not just blunder away like a witless machine. But he knew he had to teach me to walk before I could learn to talk. The same as he knew he must bring my brain alive, fully connected to the appendages and pseudo-organs it was later to use.

If he had simply disconnected my legs and arms for those first three days, my awakening brain would never have been able to use them when connected later. Do you think, if you were suddenly endowed with a third arm, that you could ever use it? Why does it take a cured paralytic so long to regain the use of his natural limbs? Mental blind spots in the brain. Dr. Link had all those strange psychological twists figured out.

Walk first. Talk and think next. That is the tried-and-true rule used among humans since the dawn of their species. Human babies learn best and most quickly that way. And I was a human baby in mind, if not body.

Dr. Link held his breath when I first tried to rise. I did, slowly, swaying on my metal legs. Up in my head, I had a three-directional spirit-level electrically contacting my brain. It told me automatically what was horizontal, vertical and oblique. My first tentative step, however, wasn’t a success. My knee-joints flexed in reverse order. I clattered to my knees, which fortunately were knobbed with thick protective plates so that the more delicate swiveling mechanisms behind weren’t harmed.

Dr. Link says I looked up at him like a startled child might. Then I promptly began walking along on my knees, finding this easy. Children would do this too, but it hurts them. I know no hurt.

After I had roved up and down the aisles of his workshop for an hour, chipping his furniture terribly, walking on my knees seemed completely natural. Dr. Link was in a quandary how to get me up to my full height. He tried grasping my arm and pulling me up, but my 500 pounds were too much for him.

My own rapidly increasing curiosity solved the problem. Like a child discovering the thrill of added height with stilts, my next attempt to rise to my full height pleased me. I tried staying up. I finally mastered the technique of alternate use of limbs and shift of weight forward.

In a couple of hours Dr. Link was leading me up and down the gravel walk around his laboratory. On my legs, it was quite easy for him to pull me along and thus guide me. Little Terry gamboled along at our heels, barking joyfully. The dog had accepted me as a friend.

I was by this time quite docile to Dr. Link’s guidance. My impressionable mind had quietly accepted him as a necessary rein and check. I did, he told me later, make tentative movements in odd directions off the path, motivated by vague stimuli, but his firm arm pulling me back served instantly to keep me in line. He paraded up and down with me as one might with an irresponsible oaf.

I would have kept on walking tirelessly for hours, but Dr. Link’s age quickly fatigued him and he led me inside. When he had safely gotten me seated in my metal chair, he clicked the switch on my chest that broke the electric current giving me life. And for the fourth time I knew that dreamless non-being which corresponded to my creator’s periods of sleep.

In three days I learned to talk reasonably well.

I give Dr. Link as much credit as myself. In those three days he pointed out the names of all objects in and around the laboratory. This fund of two hundred or so nouns he supplemented with as many verbs of action as he could demonstrate. Once heard and learned, a word never again was forgotten or obscured to me. Instantaneous comprehension. Photographic memory. Those things I had.

It is difficult to explain. Machinery is precise, unvarying. I am a machine. Electrons perform their tasks instantaneously. Electrons motivate my metallic brain.

Thus, with the intelligence of a child of five at the end of those three days, Dr. Link taught me to read. My photo-electric eyes instantly grasped the connection between speech and letter, as my mentor pointed them out. Thought-association filled in the gaps of understanding. I perceived without delay that the word “lion,” for instance, pronounced in its peculiar way, represented a live animal crudely pictured in the book. I have never seen a lion. But I would know one the instant I did.

From primers and first-readers I graduated in less than a week to adult books. Dr. Link laid out an extensive reading course for me in his large library. It included fiction as well as factual matter. Into my receptive, retentive brain began to be poured a fund of information and knowledge never before equaled in that short period of time.

There are other things to consider besides my “birth” and “education.” First of all, the housekeeper. She came in once a week to clean up the house for Dr. Link. He was a recluse, lived by himself, cooked for himself. Retired on an annuity from an invention years before.

The housekeeper had seen me in the process of construction in the past years, but only as an inanimate caricature of a human body. Dr. Link should have known better. When the first Saturday of my life came around, he forgot it was the day she came. He was absorbedly pointing out to me that “to run” meant to go faster than “to walk.”

“Demonstrate,” Dr. Link asked as I claimed understanding.

Obediently, I took a few slow steps before him. “Walking,” I said. Then I retreated a ways and lumbered forward again, running for a few steps. The stone floor clattered under my metallic feet.

“Was—that—right?” I asked in my rather stentorian voice.

At that moment a terrified shriek sounded from the doorway. The housekeeper had come up just in time to see me perform.

She screamed, making more noise than even I. “It’s the Devil himself! Run, Dr. Link—run! Police—help…”

She fainted dead away. He revived her and talked soothingly to her, trying to explain what I was, but he had to get a new housekeeper. After this he contrived to remember when Saturday came and on that day kept me hidden in a storeroom reading books.

A trivial incident in itself, perhaps, but very significant as you who read this will agree.

Two months after my awakening to life, Dr. Link one day spoke to me in a fashion other than as teacher to pupil; spoke to me as man to—man.

“You are the result of twenty years of effort,” he said, “and my success amazes even me. You are little short of being a human in mind. You are a monster, a creation, but you are basically human. You have no heredity. Your environment is molding you. You are the proof that mind is an electrical phenomenon, molded by environment. In human beings, their bodies—called heredity—are environment. But out of you I will make a mental wonder!”

His eyes seemed to burn with a strange fire, but this softened as he went on.

“I knew I had something unprecedented and vital twenty years ago when I perfected an iridium-sponge sensitive to the impact of a single electron. It was the sensitivity of thought! Mental currents in the human brain are of this micro-magnitude. I had the means now of duplicating mind-currents in an artificial medium. From that day to this I worked on the problem.

“It was not long ago that I completed your ‘brain’—an intricate complex of iridium-sponge cells. Before I brought it to life, I had your body built by skilled artisans. I wanted you to begin life equipped to live as closely to the human way as possible. How eagerly I awaited your debut into the world!”

His eyes shone.

“You surpassed my expectations. You are not merely a thinking robot. A metal man. You are—life! A new kind of life. You can be trained to think, to reason, to perform. In the future, your kind can be of inestimable aid to man and his civilization. You are the first of your kind.”

CHAPTER 2

Frankenstein!

The days and weeks slipped by. My mind matured and gathered knowledge steadily from Dr. Link’s library. I was able, in time, to absorb a page of reading matter, as quickly as human eyes scan lines. You know of the television principle—a pencil of light moving hundreds of times a second over the object to be transmitted. My eyes, triggered with speedy electrons, could do the same. What I read was absorbed—memorized—instantly. From then on it was part of my knowledge.

Scientific subjects particularly claimed my attention. There was always something indefinable about human things, something I could not quite grasp, but in my science-compounded brain science digested easily. It was not long before I knew all about myself and why I “ticked” much more fully than most humans know why they live, think and move.

Mechanical principles became starkly simple to me. I made suggestions for improvements in my own make-up that Dr. Link readily agreed upon correcting. We added little universals in my fingers, for example, that made them almost as supple as their human models.

Almost, I say. The human body is a marvelously perfected organic machine. No robot will ever equal it in sheer efficiency and adaptability. I realized my limitations.

Perhaps you will realize what I mean when I say that my eyes cannot see all colors, just the three primary hues—red, yellow and blue. It would take an impossibly complex series of units, bigger than my whole body, to enable me to see all colors. Nature has packed all that in two globes the size of marbles, for her robots. She had a billion years to do it. Dr. Link only had twenty years.

But my brain, that was another matter. Equipped with only two senses of three-color sight and limited sound, it was yet capable of garnishing a full experience. Smell and taste are gastronomic senses. I do not need them. Feeling is a device of Nature’s to protect a fragile body. My body is not fragile.

Sight and sound are the only two cerebral senses. Einstein, color-blind, half-deaf, and with deadened senses of taste, smell and feeling, would still have been Einstein mentally.

Sleep is only a word to me. When Dr. Link knew he could trust me to take care of myself, he dispensed with the nightly habit of “turning me off.” While he slept, I spent the hours reading.

He taught me how to remove the depleted storage battery in the pelvic part of my metal frame when necessary to replace it with a fresh one. This had to be done every forty-eight hours. Electricity is my life and strength. It is my food. Without it I am metal junk.

An amusing thing happened one day, not long ago. Yes, I can be amused too. I cannot laugh, but my brain can appreciate the ridiculous. Dr. Link’s perennial gardener came to the place, unannounced. Searching for the doctor to ask how he wanted the hedges cut, the man came upon us in the back, walking side by side for Dr. Link’s daily light exercise.

The gardener’s mouth began speaking and then ludicrously gaped open and stayed that way as he caught a full glimpse of me. But he did not faint in fright as the housekeeper had. He stood there, paralyzed.

“What’s the matter, Charley?” queried Dr. Link sharply. He was so used to me that for the moment he had no idea why the gardener should be astonished.

“That—that thing!” gasped the man, finally.

“Oh. Well, it’s a robot,” said Dr. Link. “Haven’t you ever heard of them? An intelligent robot. Speak to him, he’ll answer.”

After some urging the gardener sheepishly turned to me. “H-how do you do, Mr. Robot,” he stammered.

“How do you do, Mr. Charley,” I returned promptly, seeing the amusement in Dr. Link’s face. “Nice weather, isn’t it?”

For a moment the man looked ready to shriek and run. But he squared his shoulders and curled his lip. “Trickery!” he scoffed. “That thing can’t be intelligent. You’ve got a phonograph inside of it. How about the hedges?”

“I’m afraid,” murmured Dr. Link with a chuckle, “that the robot is more intelligent than you, Charley!” But he said it so the man didn’t hear, and then directed him how to trim the hedges. Charley didn’t do a good job. He seemed to be nervous all day.

One day Dr. Link stared at me proudly.

“You have now,” he said, “the intellectual capacity of a man of many years. Soon I’ll announce you to the world, you shall take your place in our world, as an independent entity—as a citizen!”

“Yes, Dr. Link,” I returned. “Whatever you say. You are my creator—my master.”

“Don’t think of it that way,” he admonished. “In the same sense, you are my son. But a father is not a son’s master after his maturity. You have gained that status.” He frowned thoughtfully. “You must have a name! Adam! Adam Link!” He faced me and put a hand on my shiny chromium shoulder. “Adam Link, first citizen of the new robot race!”

Then he frowned again. “But making you a full-fledged, legalized citizen among humans won’t be easy, I’m afraid. People will fear you and hate you at first, perhaps. I will have to introduce you to the world gradually, and convince them you are entitled to all the rights and responsibilities of citizenship because of your humanlike mind. Then, and then only, can I make more intelligent robots.”

“More robots?” I was surprised. I had not thought of it before.

“Of course,” Dr. Link said matter-of-factly. “Ever since the machine age started, man has made better and better machines. I’ve simply made the best machine of all—with a mind. Intelligent robots can help civilization. But not as slaves, or pieces of property. For then one day the robots might revolt.”

“I see,” I said, admiring his penetrating glance into the future. “If we robots are honored citizens, alongside humans, we will then work wholeheartedly in cooperation.”

“Exactly,” Dr. Link continued, his eyes shining with a visionary light. “Think of robot police! And robot firemen, robot scientists, robot lawyers, and so on down the line. The ultimate machine, with human intelligence, boosting civilization to greater heights!”

He shook himself. “Slowly, slowly. Rome was not built in a day. First and foremost, before I can make my dream come true, we must gain our first goal, Adam Link. We must make you a citizen. It may be difficult.”

Difficult? Neither Dr. Link nor I could foresee, that day five years ago, what lay ahead.

“But we’ll do it,” Dr. Link said with a firm smile. “We’ll see the day when you are—Adam Link, United States Citizen! We’ll start on the matter tomorrow.”

The next day he was dead.

It was horribly brief. I was in the storeroom, reading—it was housekeeper’s day. I heard the noise. I ran up the steps into the laboratory. Dr. Link lay with his skull crushed. A loose angle-iron of a transformer, hanging on an insulated platform on the wall, had slipped and crashed down on his head while he sat there before his workbench. I raised his slumped head to examine the wound.

Death had been instantaneous.

Those were the facts. I turned the angle-iron back myself. Blood streaked my fingers when I raised his head, not knowing for the moment that he was surely dead.

But of course, I was taken for his murderer.

The housekeeper had also heard the noise and came from the house to investigate. She took one look. She saw me bending over the body, its head torn and bloody. She fled, too frightened to make a sound.

I am not sure what your emotion of sorrow is. Perhaps I cannot feel that deeply. But I do know that the sunlight seemed suddenly faded to me.

My thoughts are rapid. I stood there only a minute, but in that time I made up my mind to leave. This again was misinterpreted. It was considered an admission of guilt. The criminal escaping from the scene of his crime. I did not realize the web I was weaving around myself.

My abrupt departure was just a desire and determination to carry out Dr. Link’s plans for me. To go out in the world and find my place in it.

To become a citizen!

Dr. Link, and my life with him, was a closed book. No use now to stay and watch ceremonials. He had launched my life. He was gone. My place now must be somewhere out in a world I had never seen. No thought entered my mind of what you humans would decide about me. I thought all men were like Dr. Link, kind and wise.

I took a fresh battery, replacing my half-depleted one. I would need another in 48 hours, but I was sure this would be taken care of by anyone to whom I made the request.

I left. Terry followed me. He was with me all the time in the events that followed. I have heard a dog is man’s best friend. Even a metal man’s.

My conceptions of geography soon proved hazy. I had pictured earth as teeming with humans and cities, leaving not much space in between, I had estimated that the city Dr. Link had spoken of must be just over the hill from his secluded country home. Yet the woods I traversed seemed endless.

Night came. I had to stop and stay still in the dark. I leaned against a tree motionlessly. Terry curled at my feet and slept. The hours passed slowly. I do not “sleep.”

“Adam Link, American citizen!” I thought to myself, wondering when that day would come.

Then at dawn they appeared—the mob. Men armed with clubs, scythes and guns. They spied me and garbled shouts went up. “Dr. Link’s robot!—the monster!—killer!” Then something struck my frontal plate with a clang. A bullet.

“Stop—wait!” I shouted, bewildered. Why was I being hunted like a wild beast? I had taken a step forward, hand upraised. But they would not listen, or explain. More shots rang out, denting my metal body. I turned and ran. Bullets might harm me, in time, if they shattered my eyes or other delicate mechanisms. Terry followed me faithfully, barking back at them.

My thoughts were puzzled. Here was something I could not rationalize or understand. This was so different from the world I had learned about in books. What had happened to the sane and orderly world my mind had conjured for itself? What was wrong?

All that day it was the same, as I ran. The party, swelled by added recruits, split into groups that tried to ring me in. They tracked me by my heavy footprints. My speed saved me each time. Yet some of those bullets damaged me. One struck the joint of my right knee, so that my leg twisted as I ran. One smashed into my head and shattered the right tympanum, making me deaf on that side.

But the bullet that hurt me most was the one that killed Terry. The posse had shot my little friend accidentally.

I was hopelessly lost now. I went in circles through the endless woods. At dusk I saw something familiar—Dr. Link’s laboratory. Blindly, numbly, I crept in. It was deserted. Dr. Link’s body was gone.

My birthplace! My six months of life here whirled through my mind. I felt sad. My two friends were gone, Dr. Link, and Terry. The shadows around me seemed to dance like little Terry had danced.

Then I found the book—Frankenstein—lying on the desk whose drawers had been emptied untidily. Dr. Link’s private desk. He had kept this one book from me. Why? I read it now, in a half hour, by my page-at-a-time scanning.

And then I understood. They thought I had “turned Frankenstein” and had killed Dr. Link, my creator. They had only one thought in mind, that I was a created monster of metal who had gone “berserk,” lacking a soul.

Adam Link, American citizen? No, it was Adam Link, Frankenstein monster.

That, I saw, was my epitaph.

Soon it was close to dawn. I knew there was no hope for me. They had me surrounded, cut off. I had not been so badly damaged that I could not still summon power enough to run through their lines and escape. But it would only be at the cost of several of their lives. And that was the reason I stayed my hand against them, as the yelling mob stormed in.

Clubs and guns were raised against me. Hate was in their faces. I closed my eyes, to shut out the sight. It was the end, my thoughts said, of Adam Link, the first of intelligent robots—and the last.

CHAPTER 3

My Arrest

I opened my eyes, astonished, a moment later. I looked around and saw the group of men who had hunted me down. But they had stopped. Why hadn’t they smashed and pounded me to broken wheels and scattered mechanical parts?

Then I saw the blazing-eyed young man facing them. The armed party was muttering and waving their weapons at me, but my unexpected champion had evidently halted them.

He turned to me now. He was young, firm-jawed, and vaguely familiar in some way. He had grey intelligent eyes. I liked him instantly. Though I am a robot, I form likes and dislikes among the humans I meet.

“Are you all right—Adam Link?” he asked. He added the name given me by Dr. Link with some hesitation, but clearly. He was addressing me as one living entity to another. To use a more appropriate expression—as man to man. Only one other had ever done that—Dr. Link.

I arose from my sitting posture, in which I had been since I had turned myself off. I nearly toppled over. One of my legs was badly twisted. I took swift appraisal and noticed the dents on my metal-wrought shoulders and chest. The top of my skull-plate too, was dented, pressing down slightly on the electrical brain within. From that, for lack of a better term, I had a headache.

Obviously, I had been saved just in time. The enraged, vengeful posse had begun to smash me. But no vital harm had been done.

“I can be repaired,” I replied. The armed men fell back uneasily at the sound of my microphonic voice. Why are humans so afraid of that which they cannot understand? Then I looked, at the young man, wishing I could show gratitude.

“Thank you for what you have done,” I said. “Who are you?”

“I’m Thomas Link, Dr. Link’s nephew, and his closest living relative,” he said. Instantly I saw the family resemblance, and knew why he had seemed so familiar, though I had never seen him before.

He went on, speaking to the others as much as myself. “I have been practicing law, in San Francisco. I hurried here when I heard of my uncle’s death. He has left everything to me. I see I have come just in time to prevent the destruction—the wanton murder, gentlemen—of Adam Link, my uncle’s intelligent robot.”

“Huh—murder,” said the leader of the men, scoffingly. He was the county sheriff and carried a high-powered rifle under his arm. “This—this thing isn’t a man. It’s a machine. A clever diabolical machine that killed your uncle in cold blood.”

“I don’t believe it,” snapped young Tom Link quickly. “My uncle wrote me many letters about this robot. He said it was as rational as any human being. Perhaps more so than you, sheriff. And not in the least dangerous, in any remote Frankenstein way. My uncle was a clear-headed thinker and scientist. What he said, I accept. You will not destroy this robot.”

The sheriff’s face reddened. Tom had been rather tactless in comparing him and myself. “We will!” he shouted. “It’s a dangerous monster. As the representative of the law in this matter, it is my rightful duty to protect the community. If a tiger were loose in this county, I would destroy it.” He raised his rifle and the men behind him muttered with rising feelings.

I wonder if I have an emotion akin to your human anger? He had compared me to a tiger! I know what a tiger is, from my extensive reading. My electronic brain hummed, and I started to speak, but Tom Link motioned me silent.

“Stop, sheriff,” he said warningly. “The robot—if you choose to consider it that way—was part of my uncle’s property. Now it is my property. I am a lawyer. I know my rights. If you touch the robot, I’ll sue you in court for willful destruction of a piece of my property.”

The law officer gasped. “Well—uh—” He began again, lamely. “But this is different. This robot is a moving, li—no, not living—but anyway—uh—it’s a creature, and—” He was too muddled by the sudden change of concept to go on.

Tom Link smiled. I suddenly perceived that he was a very clever young man. He had planned this trap. “Right, sheriff,” he said quickly. “This robot is a creature. It is not an animal, for animals don’t talk. It is a manlike being. Therefore, like any other talking, thinking man, he is entitled to a court trial.” The sheriff tried to remonstrate, but Tom hustled him out, and the other men with him. “If you want to continue prosecution of Adam Link, the intelligent robot,” was Tom’s parting shot, “come back with a warrant of arrest.”

Tom turned to me when we were alone. “Whew!” He wiped his forehead. “That was close.” Then he grinned a little, thinking perhaps of the utterly confounded look on the sheriff’s face. I grinned, too, within myself. It is a feature of intelligence—whether in a human body or metal—to see humor in that which is ridiculous.

I was still, however, a little puzzled. “Tell me, Tom Link,” I queried, “why you have so completely taken my side? All others, except your uncle, hated and feared me from first sight.”

Instead of answering, Tom rummaged in his uncle’s private desk. At last he withdrew a document and let me read it. I did not quite grasp the complicated legal language, but I noticed the word “citizen” several times.

Tom explained. “My uncle, if he hadn’t died so unfortunately, was fully determined to make you a citizen, Adam Link, as you know. He had begun to take up the matters of legal records to prove your ‘birth’, education and rightful status. He corresponded with me on these details at some length. In another month, I was to have come here to complete the negotiations.”

I remembered Dr. Link’s repeated remarks that I was not just a robot, a metal man. I was life! I was a thinking being, as manlike as any clothed in flesh and blood. He had trained me, brought me up, with all the loving kindness, patience and true feeling of a father with his own child.

And now, with the thought of my creator, came a sadness, an ache within me. I felt as I had that day I discovered him dead, when the sunlight had seemed suddenly faded to me. You who read may smile cynically, but my “emotions,” I believe, are real and deep. Life is essentially in the mind. I have a mind.

“He was a good man,” I said. “And you, Tom, you are my friend.”

He smiled in his warm way, and put his hand on my shiny, hard shoulder. “I am your cousin,” he responded simply, “Blood is thicker than water, you know.”

No play of words was intended, I knew that. I can only say that I have never heard a nobler expression. In simple words, he showed me that he accepted me as a fellow man.

The rest of that day, Tom Link went through his uncle’s effects while he talked to me. I told him the full story of his uncle’s accidental death and the following events.

“We have a battle ahead of us,” he summed it up. “The battle to save you from a charge of manslaughter. After that, we will take up the matter of your—citizenship.”

He glanced at me just a little queerly. His eyes traveled from my mirrored eyes and expressionless metal face down to my stiff alloy legs. Perhaps for the first time, it occurred to him how strange this all was. He, a young lawyer, out to defend me, a conglomerate of wires and cogs, as though I were a human being, conceived by woman. For a moment, he may even have had doubts, now that the excitement was over and he had a chance to think about me.

Might I not be a monster after all? Might Dr. Link not have been wrong in saying that I was the opposite of my fearsomely fabricated exterior? Who could know what weird thoughts coursed through my unhuman, unbiological brain? Might I not just be waiting for the chance to kill Tom, too, in some monstrous mood?

I could sense those thoughts crowding his mind. I don’t think it’s a telepathic phenomenon. It is just that my electron-activated brain works instantaneously. The chains of memory-association within me operate with lightning rapidity. The slightest twitch of his lip and inflection in his voice revealed to me the probable thought causing them.

I felt a little disturbed. Was my only friend to gradually turn against me? Was my cause hopeless? Was it a foregone conclusion that such an utterly alien being as myself could never be accepted in the world of man? I was like a Martian, suddenly descending upon Earth, with as little possibility of achieving friendly intercourse. You think the comparison irrelevant? I will guarantee that the first Martians, or other-world creatures, to land on Earth—if this event ever occurs—will be destroyed blindly. You humans do not know how strong and deep within you lies the jungle instincts of your animal past. That is, in the majority of you. And it is not necessarily those in high places who are more “civilized.” But I digress again.

While Tom was busy, I repaired myself. I am a machine, and know more about my workings than any physiologist knows of his own body. I straightened the knee-joint swivel mechanism, twisted by a bullet. Two of my fingers had broken “muscle” cables which I welded together. I took off my frontal chest plate and hammered out the dents. My removable skull-piece allowed me to release the pressure on my sponge-brain. My “headache” left.

Finally I oiled myself completely, and substituted a fresh battery in my driving unit. In a few hours I had gone through what would correspond in a human to surgical patchings, operations and convalescence that would have taken weeks. It is very convenient having a metal body.

Then I went out. I wandered in the woods and came back with little Terry’s half-decayed body. I buried him in the backyard, thinking of his joyous barks and the playful times we had had together.

“Adam! Adam Link!”

I started and turned. It was Tom behind me, watching. His face was self-reproachful.

“Forgive me,” he said softly. “I was doubting you, Adam Link, all afternoon. Doubting that you could be as nearly human as my uncle wrote you were. But I will never fail you again.” He was looking at Terry’s fresh grave.

As Tom had predicted, Sheriff Barclay promptly appeared the next morning, with a warrant for my arrest. He was determined to have me destroyed. Since he couldn’t do so directly, without legally entangling himself in a suit, he had taken the other course.

“It will be a damned farce—holding a trial for a robot,” he admitted shamefacedly. “I feel like a fool. But it must be destroyed. You’re rather clever, young man, but you don’t think a jury of honest, level-headed men is going to exonerate your—uh—client?”

Tom said nothing, just set his jaw grimly.

Sheriff Barclay looked at me. “You’re—uh—I mean it’s under arrest. It must come with us, to jail.” He was speaking to Tom, although he watched me narrowly, expecting me, I suppose, to go berserk.

“I’m coming along,” nodded Tom. “Come, Adam.”

They had brought a truck for me—I am a 500-pound mass of metal—and drove me toward the nearby town. I had never been in one before, having lived in seclusion with Dr. Link at his country place. My first glimpse of the small city with its 50,000 inhabitants did not startle me. It was about what I had expected from my reading and the pictures I had seen—noisy, congested, ugly, badly arranged.

A curious crowd watched as I was paraded up the courthouse steps. The news had gone around. They watched silently, awestruck. And in every face, I saw lurking fear, instinctive hatred. I had the feeling then, as never before, that I was an outcast. And doomed.

The scene in the courtroom was, as the sheriff had predicted, a sort of solemn farce. The presiding judge coughed continuously. Only Tom Link was at his ease. He insisted on the full legal method. There had been an inquest of course before Dr. Link’s burial, in which it was established that a heavy instrument had caused death. Nothing could gainsay that my hard metal arm might have been the “instrument of death.”

I was indicted on a manslaughter charge for the death of Dr. Charles Link, and entered in the record as “Adam Link.”

When that had been done, Tom heaved a sigh and winked toward me. I knew what the wink meant. Again a trap had been laid, and sprung. Once my name was down in the court record, I was accorded all the rights and privileges of the machinery of justice. As I know now, if Sheriff Barclay had gone to the governor of the state instead, he could have obtained a state order to demolish me as an unlawful weapon! For I was a mechanical contrivance that (circumstantially) had taken a life.

Tom could not have squirmed out of that charge. But Sheriff Barclay had missed that loophole. With my name down, I was a defendant—and had human status.

Two newspaper reporters were present. One of them was staring at me closely, wonderingly. He came as near as he could, unafraid. Unafraid! The only one in the room, besides Tom, who did not fear me instinctively. He, too, could be my friend.

I saw the question in his eager young face. “Yes, I am intelligent,” I said, achieving a hissing whisper, so no one else would hear.

He started, then grinned pleasantly. “Okay!” he said and I know he believed. He began scribbling furiously in a notebook.

The formal indictment over, the bailiff led me to my cell and locked me in. Tom smiled reassurance, but when he left, I felt suddenly alone, hemmed in by enemies. You humans can never have quite that feeling. Unless, perhaps, you are a spy caught by an enemy nation. But even then you know you are dying for a cause, a reason. But I was being doomed—exterminated—for little else than not being understood.