9,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Hamad Bin Khalifa University Press

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

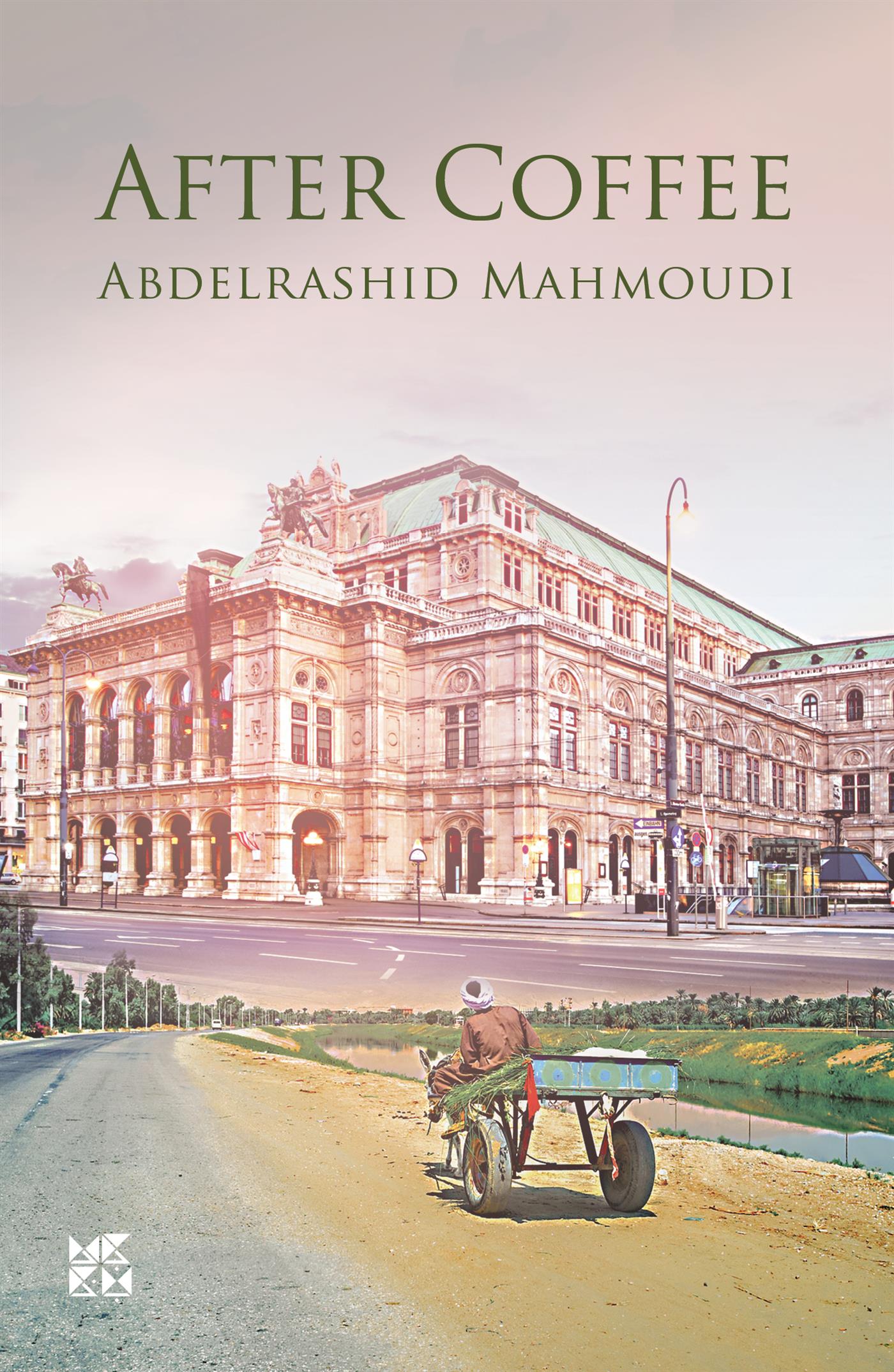

Medhat is an orphaned boy who grows up shuttling between various farming families in the beautiful province of Sharkia, east of the Nile Delta. What was intended to be a brief visit for the five-year-old to Ismailia, a beautiful and cosmopolitan city in the Suez Canal zone, ends up being the beginning of a nomadic life no one could have imagined. Medhat’s journey takes him across the many landmarks of Egypt and beyond, all the way to Vienna where he discovers that his feelings of displacement still haunt him to the core. In a narrative that interweaves aspects of Egyptian folklore, epic prose, and classical literature, the author skillfully presents the conflict between the man in exile who reflects longingly on his history and origins, and the village boy who belonged nowhere.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2020

Ähnliche

The Wolf Slayer

Khalil tossed and turned outside his shop, which overlooked the canal. He batted a fly that hovered over his nose, then dozed off again. The breeze toyed with the hem of his jilbab, as if it wanted to pick up the fabric and fly off. Nothing disrupted the serenity of this scene until a noise surfaced - a cacophony of screaming, laughter, and barking - from the direction of the canal. A group of boys was crossing over while a black dog protested over how they’d charged towards the water without him. The boys were fleeing from the Upper Egyptian locals with their loot: dates, prickly pears, and reeds. Khalil woke up when the boys’ commotion reached him, and all traces of sleep disappeared once the afternoon call to prayer sounded from the farthest end of the village. It felt as if a firm hand was shaking him, urging Khalil to get up and go to the mosque to pray on time, but he didn’t budge. Those little devils were still running riot, even though they usually panicked and scampered off to their hiding places once the blistering midday hour had passed. After the shame of what had happened with his sister, Khalil felt no desire to do his ablutions or pray. He wished he could sleep and never wake up. He didn’t want to talk to anyone about anything. His customers no longer had anything to say to him, either. They each grabbed what they needed before hurrying off. No one would stay and sprawl out on the ground outside his shop anymore to play cards, drink tea, and smoke muassel. All that had ended, and anyway he didn’t want to face them. He saw the question in people’s eyes, which nobody dared to utter: ‘Where did she go?’ Every time a customer appeared, he lowered his head. He had transformed from an intimidating character to a man broken by the weight of shame and helplessness, all over what his sister Zakiya had done. What’s the use of having a shop and buying and selling when you can’t talk to anyone? Wouldn’t it be better to stay at home and let no one see your face? He finally stood up to close the shop. But what’s the point of staying at home? he wondered. There was only one person to turn to for help: Ibrahim Abu Zaid.

He walked past Nafisa’s house. The old woman was outside chasing her chickens with a broomstick - a dried palm branch with its strands still intact - to bring them in for the night. She wouldn’t usually do this before sunset, but had decided to bring them in early that day. As Khalil walked by, he turned his head to avoid greeting her. He had started to despise the old woman because his sister used to go to her house and work for free. ‘I hope you’re well, Khalil,’ Nafisa called out to him, but he didn’t reply.

‘You bear a heavy burden, my boy,’ she added, when he was further away. ‘God help you, my dear.’ Still, the fact that he’d ignored her had stung. She didn’t deserve that. Whatever had happened had happened, and she was not to blame. Medhat had also passed by her house a short while ago with his dog and his friends, on their way back from the opposite bank of the canal, brandishing their reed sticks. ‘Come here my darling,’ she had called out to him. ‘Give your nana a kiss, my love.’ But the boy stopped to say with disdain, ‘I don’t kiss old people.’ ‘Come here boy, be kind,’ she said. ‘I’m your nana, your darling nana.’ ‘When you take off your nose ring,’ he replied. That scrawny kid is only five years old, she thought as she shook her head. You’d think he was spawned by devils. God rest the souls of your mother and father, Medhat. Then she sighed. ‘But then again, who does like old people?’

She was the last of the grandparents’ generation. Back when she lived with her late brother’s wife, Zainab, she was treated like a queen. But after Zainab died, she went to live with Fatima, Zainab’s second cousin, until she grew weary of the way Fatima’s daughters treated her. The girls also don’t like my nose ring, like Medhat, she thought. ‘What is that hanging from your nose, Nana?’ they would say. ‘No one wears those anymore.’ They didn’t like the tattoo on her chin, either. And they would never let her utter a single word without making fun of her. ‘Nana never stops talking,’ they would say, or - even worse - ‘My nana’s started spouting gibberish.’

They liked her food, sure, they would devour it - all the old recipes she carried in her heart - but they didn’t want her to speak. Fatima had asked her to teach her eldest daughter the basics of cooking, in preparation for marriage, but could Saadiya endure her instructions and advice? ‘Nana, you’re driving me crazy with all this talk about how much water to add to the rice, because you say perfecting the rice is the stamp of a good cook. And the tomato sauce that has to be stewed just so... Do you think the man will be as bothered as you? Why can’t he just be quiet and eat whatever I cook?’ At first, Fatima would tell her daughters off, but she soon changed. After she got fed up with Nafisa’s rambling about her missing son and her relentless, futile appeals to him, she gradually began to let their comments go. Whenever the memory of his absence became too painful, Nafisa would find somewhere private and start crying out, imploring him to come home. After Fatima gave up on her, she gathered her belongings and moved to this house that turned its back to the village, facing the country road instead. Here, no one had any right to complain about her, and she could see out her remaining years in peace. And here, she could wait for her absent loved one. Thirty years had passed since her son Hashem was whisked off to the provincial jail. It was said the police found him and the rest of the gang because one of them had left behind a sandal as he fled the scene, which is how the police dogs were able to trace them. She had seen one of them return - Musa Abu Mostafa. He had stepped out of the police van supported by two policemen because he couldn’t walk on his own. After fifteen years in prison, he was back, but the happiness of his wife and children was short-lived. Shortly after reaching his house, he lay down and never got up again. He died after spending barely a week with his family. When she saw him clambering out of the police van, she knew he didn’t have long. Having witnessed pangs of death in both the young and the old, she had come to recognise the meaning behind his pallor.

But her son Hashem never came home, not even after the end of his prison term. The rumour was that he had escaped prison and fled to Palestine. It was also said that he was spotted several times wandering the fields on the other side of the canal, near the Sa’ida, or Upper Egyptian, village. So why hadn’t he returned? Hashem, why won’t you come back home? She recalled his life from the day he was born, including the time she found him a fiancé, and how she had tried to hasten his wedding so she could become a grandmother, since he was her only son. She would return to her memories of each event as if it had happened yesterday, without skipping a single moment. She remembered the date, the season it fell in, what food she had prepared, and the colour of the chicken’s feathers that she had slaughtered for the occasion. One of Fatima’s daughters would interrupt her. ‘Nana, do you have to go into so much detail? Do you really have to tell us about the rooster you slaughtered for the guests, how heavy it was, how its feathers were black and that its crest was large?’ No one wanted to listen to her tales of sorrow.

Ever since she’d started living alone, the days had dragged and the nights even more so. Her visitors slowed to a trickle. Her family began to forget about her. Zaki no longer dropped in on her. He used to stop off after his afternoon nap, before the asr prayer, to see if she had anything he could snack on. She would bring him whatever he wanted - a hot loaf of bread, some crushed salt and chilli pepper. Zaki was the only one who was still faithful to the old days, and the only one whose heart still went out to everyone. But she didn’t know what had happened to him lately. His visits had dwindled and, when they did happen, they were fleeting. His face seemed permanently strained.

Salama - may God prolong his life and protect him from danger - was the only one in her family who still cared about her. He farmed her land, was content with his share of the harvest - a quarter - and never refused her a single request. He also helped to sell her share and brought everything she needed from the Monday or Wednesday markets. ‘The boy is gallant and chivalrous and has a kind heart, but what kind of a nightmare has he caught himself up in?’ she wondered. There was no one left but Zakiya - the Baharwa girl - to help her with household chores like kneading the dough, baking, and washing. Guided by the Most Merciful One, she did it all for no wage, even though the Baharwa people were famous for being tightfisted. Then, the One and Only God ordained that this calamity would fall on her and Salama. Nafisa started to worry that Salama and Zakiya would end up as unlucky as Hashem - he, too, had been kind, chivalrous, and naïve. But still, God had brought a catastrophe down on him, great is His wisdom. She worried they would end up doomed like Zainab’s youngest and most handsome child. He was the one known as ‘the star’ and ‘the neighbourhood heartthrob’, before he was lured by some thugs, became addicted to ‘snorting powder,’ and ended up dying at one of those gatherings. Over the years, she had seen how misfortune only ever remembered the kind ones. Hashem, for example, didn’t murder anyone, and none of that gang had any intention of killing a soul. They were a bunch of misguided youths and the devil used them as his playthings. May God avenge them. That gang leader sent respectable kids to hell while he dozed at home so he could escape the consequences as smoothly as a strand of hair teased out of a lump of dough. They had wanted to rob the home of a widow in the Nazlet Elwan village to steal her silver, but she woke up and confronted one of them, who stabbed her with a knife. It was an accidental blow. But Hashem didn’t attack anyone; he didn’t clash with anyone and hadn’t even gone into the house. He’d been standing guard at the top of the road ready to whistle if he saw anyone approaching. ‘Why did you do it, when you came from a good family?’ she moaned. ‘Did you need any gold or silver? Why then, when you’re the one who always gives away everything you have? Why not come home, my son? My heart is tired of waiting, Hashem. They say you come to the other side of the canal at night. So take a little turn, my darling. Say, I’ll go and see my mother whose tears have run dry. Hashem, there’s nothing but a canal to separate us. You can cross the water by foot.... They are just a few short steps, my sweetheart.’ When she had managed to usher in the last chicken, she fastened her door shut with a latch and key.

***

Hajj Zaki was the first to appear when the worshippers began arriving at the mosque in answer to the afternoon call to prayer. He circled the building to inspect its condition and reached the back door, pursing his lips with discontent. His brother still lifted water out of the mosque’s well to fill the bathing basin, as well as the place for ablution and the latrines. He also raised the prayer call at the regular times with a booming voice that travelled across the canal and was heard at the Sa’ida’s village - a beautiful sound that humbled people’s hearts. But lately, it had started to cause a tightness in Zaki’s chest. And the building was in a deplorable state; the wall by the well had large cracks in it that warned of imminent collapse. He appealed to the Muslims to rescue their mosque before it caved in, but none of the Qassimis or the Baharwa people were interested in his pleas. No one wanted to pull a piaster from their pocket to help repair the house of God. They wanted him to bear the burden on his own, as he had in the past, but he couldn’t do it anymore. The mosque was old, built in his grandfather’s time, and his father had taken charge of its upkeep throughout his whole life. As for the others, their hearts had toughened and their faith weakened. He sighed. The families of the neighbouring villages used to come for Friday prayers, but now their attendance was rare. He recalled painfully how he used to invite everyone after the prayers for lunch at the guesthouse they called the seera, serving them lentils in winter and rice pudding in summer. That was in the good old days. An onion shared with a loved one is a lamb, as the saying goes, but this loved one had neither lamb nor onions anymore.

He stopped to shoo away the boys who had gathered around the back door. They were carrying sticks made of reed, and some were as naked as the day they were born. The pack started to disperse but two lingered: Medhat and his black dog.

Medhat was rooted to his spot by the door and gazed out at the far corner of the mosque where a rectangular wooden box stood, tipped upright on four legs. They called it ‘the coffin’. He would always see it there, in the same place, unless it had been removed by the village men as they hauled someone inside it to a distant place from which there was no return. This had happened when they carried his mother away and when they took his grandmother, covered in a white sheet that fluttered in the breeze. He may never have discovered what all this meant had he not wondered why neither his mother nor grandmother had come back from that faraway place. ‘Where’s my ma?’ he had asked Na’sa, his wet-nurse. ‘She went to the market to get you halva and a couple of loaves of special bandar bread,’ she replied. ‘And where’s my nana?’ he asked her. ‘She went to visit her relatives in Hassiniya,’ she said. Oh, how he’d waited for his mother to return with the halva and the special bread. And how he’d waited for his grandmother to come back from her family visit. But he now knew that Na’sa had lied and that anyone carried off in that box would not be back. That was the distant place they called ‘death’.

One of his friends pulled at his arm and another struck him on the shoulder with a stick, but he didn’t move. They were gesturing excitedly with their reed sticks because they were on their way to war…their mission at this hour was to attack the wasps that built their nests in the straw and firewood stored on the roofs of the houses. They were not deterred from battle by the fact that wasps defended their homes fiercely and were capable of inflicting serious injuries on the attackers - especially the naked ones. The child didn’t budge until Hajj Zaki put his hand on his shoulder. ‘Isn’t it rude to walk around naked like that, Medhat?’ ‘We left our clothes by the canal,’ Medhat replied. ‘We sped off when theSa’ida’s dogs started chasing us’. ‘All right, but hurry on along now please,’ Zaki said. ‘Goodbye.’

The two sheikhs, Hamed and Sayyid, approached, but stepped aside from leading the prayer when they saw Hajj Zaki. It wasn’t because he was more educated than them, since he hadn’t studied at al-Azhar Islamic University. And it wasn’t because he was older, since he was actually younger than them both. It was because they recognised his stature. If he wasn’t there, they would have ended up competing over who would lead the prayer and some of the congregation might have sided with one or the other, since they each had their own supporters. The first one, Sheikh Sayyid, had spent God knows how many years boarding at the revered University of al-Azhar without receiving a graduation certificate. As for the second sheikh, Hamed, he had spent only five years at the Religious Institute of Zagazig. Thus Sheikh Sayyid believed, along with his supporters, that it was his right, being the more educated, to lead the prayers. But Sheikh Hamed believed, and so did his supporters, that to pray behind Sheikh Sayyid was an arduous ordeal because he would forever stutter and stammer. And from time to time, he would emit a sound that resembled a cross between a sip and a slurp, and he would end up reciting the rebellious phrase or word over and over again until it obeyed him. Not only that, but these falterings that seemed to haunt Sheikh Sayyid would prompt the boys in the back rows to snigger and nudge each other, or worse. Sheikh Hamed, however, was characterised by his wit and eloquence. Most importantly, he would complete the prayer before the worshippers’ patience had completely depleted, knowing that some of them wanted only to carry out the religious obligation in a slapdash manner. And so he would leave no room for the devil to penetrate the rows of worshippers and distract them from their state of submission as they stood in the hands of God.

If Hajj Zaki was present, it meant the end of the dispute; everyone would be in agreement, tranquillity would abound, and the prayer would be performed as it should be. Even Shabana, whose mockery no one could escape, would declare during his gatherings at the village’s public jurn that ‘Saad Pasha and Nahhas Pasha may be the elected leaders of the nation, but my cousin Zaki is the chief of the “sons of Qassim”, without election or royal decree.’ But this unelected leadership no longer pleased Zaki, since it had become too heavy a burden to bear. It had somehow been thrust upon him through neither his nor anyone else’s will but God’s. He was simply performing his duty, just as he had when his father was alive. Back then, he would receive guests generously and would sometimes act on his father’s behalf in resolving conflicts. But he just couldn’t keep doing it anymore; God burdens not a person beyond his scope, after all.

He called for the worshippers to straighten the rows as he led the congregational prayer so that ‘God may have mercy on you’, and everyone shuffled into position behind him. There was still some respect left. No one complained, no arguments erupted, and the boys didn’t nudge each other in the back rows or snigger if the prayer dragged on. And so everyone was humble in the hands of the Sacred King. The crisis now was that he himself struggled to stay humble and focused. His mind would wander just as he started to recite a verse from the Quran, and he would try to remember the next one, but it would only come through arduous effort. Between one verse and another was a gap filled with silence, a gap mired in darkness. Between one verse and another, fear reared its head. And recently - since the quarrel with his brother - these gaps had been growing. If this continued, people would surely abandon him. Then there was Shabana at the jurn gatherings; if people found out about his situation, there was no way he would escape Shabana’s ridicule. Fear resided deep inside him, and it surfaced during the prayers, or as soon as he laid his head on the pillow, or whenever he saw his brother. There was a phrase that was desperate to launch itself from the depths of his soul towards his lips in the shape of a scream, but it would always get lodged in his throat. And there were words he wished he could raise to the One from Whom Nothing is Concealed, but he found himself mute.

***

The village of the Qassimis, the descendants of the original settler, Qassim, was an odd kind of place, surrounded by secrets on every side. Most of the locals believed jinn inhabited the mosque’s well, and it was said that a black, horned serpent guarded the bathing basin of the mosque. Sheikh Sayyid claimed that ‘The Enemy’ extended his hand and poked him on the right side of his body, trying to nullify his prayers, whenever he performed the voluntary, late-night tahajjud. Beyond the fields that extended south of the mosque was a stagnant pond with algae that rose above the water’s surface. People would try to keep their distance as they walked past, because it was said to be deep, bottomless, and inhabited by various types of ghouls. Woe betide anyone who lost their footing and toppled in! The main road that split the village in two ended at the perpendicular country road that bordered the canal. Those were the northern borders of the village. But beyond those borders was the opposite bank of the canal, where the Sa’ida lived. There was some interaction between the Sa’ida people and the villagers, and they would sometimes visit each other. The village children would also cross to the other side on foot when the water was shallow - since the canal was four metres wide at most - or swim across during the periods of flooding. They would climb the Sa’ida’s palm trees to steal their fruit in the date season. And they would chop up the reed branches they found floating on the surface of the water to use as spears that they would fling at wasps, or make reed pens to use at the Quranic school. Crossing to the opposite bank would fill the boys with fear and, to them, reaching the other side was an adventure to top all adventures.

At the western side of the village there was the waterwheel, shaded by the old sycamore tree whose branches extended over the path. The well at the waterwheel was inhabited and had its own tales of terror. It was said that a man called Abdulhadi had been mesmerised by a female jinn - one of the women of the underworld - while he watered his land one night. She had appeared to him from the well and forced him into an engagement, offering to take him to live down in the abundant bliss amongst her family. But he refused because he was faithful to his wife, the mother of his children. It was also said that he was strong and fought with her until she defeated him. She only managed to overcome him when she embraced him, pressing her breasts into his chest such that two nails protruding from her nipples hammered into him and pierced his heart. When was this? And to which past generation did Abdelhadi belong? And where was his wife whom he’d abandoned? And where were his remaining family? These were questions for which no one had answers. It wouldn’t even cross anyone’s mind in the village - apart from Shabana at the jurn gatherings - to ask them. There was another story about a young man called Abdelsalam who was enticed by a female jinn and disappeared with her to live together in her underground world, where they have remained ever since. Who were his mother and father? In which era did he live? These questions had no answer and no one except Shabana thought to raise them, to ridicule the sons of Qassim and to highlight their foolishness. If ever the water buffalo’s hoof slipped when it was in the vicinity of the waterwheel, causing it to topple into the well, it would be taken as an ominous sign and a harbinger of great catastrophe. The women’s voices would then ring out as they screamed and wailed, and the men would rush from the outskirts of the village to the helpless animal to try and pull it out. If they failed to rescue it, they would bring a knife and slaughter the buffalo on the spot before it died.

The area around the waterwheel was inhabited, too. There was a spirit that appeared to passersby at night in the shape of a donkey whose back rose higher and higher until it was taller than the top of the sycamore tree and even reached the sky. If anyone approaching from the western side at night was destined to come across a spirit, then they would most likely spot it near the waterwheel and the sycamore tree. And it would be that satanic donkey they’d see.

This paranormal activity wasn’t restricted to the western side of the country road, since the eastern side had its peculiar stories in turn. There, the spirits would not be limited to nocturnal appearances. Either ‘Mother Ghoul’ or ‘The Summoner’ might emerge in broad daylight, and especially during the siesta hour. Everyone would be asleep, and all the animals would appear stunned - the water buffalo, for example, would be powerless to bat the flies pinching at its tail - and the whole area around the jurn would be vacant. But people returning from the central market on Wednesday might be unfortunate enough to be heading back during the witching hour and could be half-asleep astride their donkeys when they would suddenly be woken up by the call of ‘The Summoner’. Then woe betide those who responded, for the call was irresistible.

The world at large was divided into two: the countryside and the bandar. The bandar was the world of civilisation and luxury. The nearest town would not be considered bandar, nor would thecapital of the province,orthe provincialcitiesin general. Those areas were in between, only partially civilised. Cairo would be classified as bandar, and perhaps Alexandria too, since many of its residents were said to be foreigners.

But what was the secret of the spirits’ fascination with donkeys? The question was once put to Shabana.

‘Donkeys are easy to ride. If someone passing by obeys the devil and rides it, then they’re doomed. It’s the same with women. A woman entices you until you ride her and end up in hellfire. Ha ha ha!’

He laughed, and so did his audience. But his words seemed to carry a hint of cunning. Was he also alluding to what had happened to Salama and Zakariya?

***

Sheikh Hamed left the mosque, putting his hand out for his son to grab. He was with Sheikh Sayyid, who was swaying as usual as he walked, listening so as not to miss the sound of any invisible caller. Sheikh Sayyid was surprised when Sheikh Hamed invited him to drink tea at his house. How could that be? Hamed was not known for his generosity. So what did he want? Oh, You who conceals benevolence, rescue us from what we fear. He tried to evade him but failed, since Hamed insisted.

‘Come on man, shame on you. How can you refuse a brother’s invitation?’

Dear God, let it be good news. He sat down reluctantly, and then the reason became clear. All his astonishment disappeared when Hamed - before the tea had even arrived - floated his question. ‘Sheikh Sayyid, I swear, this whole business with Salama is making me very unhappy. Is there any news? Has he turned up yet?’ Sheikh Sayyid lowered his head for a long time, then took out a large thin needle from his turban, with which he started to darn his sandal. He never left his house unarmed. Tucked under his arm was Sheikh al-Bajouri’s book of jurisprudence, and he had a large needle in his turban to mend his sandals, and a smaller one for the jilbab and such - oh, what a multitude of repairs! So the reason had become apparent: Sheikh Sayyid wanted to lure him into talking about his son, but he didn’t want to broach that unstoppable evil. At first, he pretended he hadn’t heard the question, until he was inspired, after one or two stitches, to distract Hamed from his goal.

‘So here we are, with Ramadan at our door,’ he said. ‘What will you do?’

‘Yes, you have touched on the wound now,’ Hamed replied. ‘What will I do in Ramadan? God only knows.’ He shook his head sadly. ‘God bless the good old days. They’re over, Sheikh Sayyid. In the old days, as you know, Hajj Zaki - may God improve his lot - would invite me to celebrate the righteous month with him in the seera. At sunset, with the sounding of the maghreb call to prayer, the food would be served to break the fast. And what about the abundance: the poultry, the lamb, the stuffed vegetables and the fatta. Abundance followed by more abundance. And another feast would be prepared for the pre-dawn meal to prepare for fasting. Yes. Those were the days…’

‘And between breaking the fast and the pre-dawn meal there would be stories, tales and poetry,’ Sayyid said.

‘Exactly,’ Hamed replied. ‘Stories, tales and poetry. I would recite a few pages of the Quran between the maghreb prayer and the early morning meal. And between one reading and another, we would tell stories and recite poetry. But as you can see, Zaki - may God help and support him - cannot arrange all of that anymore, not since his brother took his share of the land and separated from him. But what can I do? The fathers of the children I teach at the Quran school only give me a kilo of wheat or corn each. It’s like pulling teeth. They want the kids to learn for free. I swear to God, have you ever seen anything as catastrophic as this?’

Sayyid was starting to enjoy the game, so he continued.

‘By the way, I once heard you tell the story of the woman who married the caliph Muawiya ibn Abu Sufyan. Would you remind me again how the story goes?’

It pleased Hamed that his friend had asked him to recount one of the stories that were dear to his heart, and which he had told countless times at Ramadan night gatherings, so he cleared his throat.

‘Do you mean Maysun bint Bahdal?’ he replied. ‘What a woman, Sheikh Sayyid! She was a beauty and the caliph Muawiya - may God be pleased with him - married her and installed her in a palace where she had everything she needed and more, but she longed for her old life in the desert. Can you believe how that respectable woman acted.... Then one day, the caliph walked in on her singing:

A rickety tent that the wind howls through is dearer to me than a towering palace. To wear a coarse abaya and a joyful soul is dearer to me than some fine, sheer silk.Nibbling crumbs of our homemade breadis dearer to me than gorging a loaf. The whistling of the wind along the mountain paths is dearer to me than a tambourine’s beat. A dog who growls at a visitor in the night is dearer to me than a friendly cat.

A kind-hearted thin man from my family is dearer to me than some broad foreigner.The rough life I lead as a desert Bedouin is dearer to me than this opulent one. Instead, all I want is my homeland, that place of honour is enough for me.

So he pronounced her divorced, three times for confirmation, and sent her back to her family. Honestly, have you ever seen anything as marvellous, or more admirable behaviour than that of the prince of the believers, Muawiya, the companion of the prophet of God?’

‘God bless you.’ Sayyid said. ‘There you have the moral in front of you, so you should heed it. Tell me, how can you recite this poem that advises self-restraintandmoderation and, at the same time, mourn the days of poultry and stuffed vegetables? Would it not be more fitting for you, Hamed, to be content with whatever blessings God has given you, no matter how modest?’

Hamed paled. It took him a few moments to recover from the shock.

‘Thank God for everything, but the little that is left is not enough to survive on. You don’t realise. I swear to God Almighty, Sheikh Sayyid, even the mice at home are starving. Even the mice cannot find any food to eat. So what do they do? Human beings are the only things left for them. Last night, as I was sleeping, one of them - may God thwart his plans - was about to munch on my toe. I woke and found the bastard biting it. And I will not lie to you, I have no appetite for stories and poems. Ramadan is on its way and there will be nothing left but fasting during the day and hunger at night. But what can we say? Complaining to anyone but God is humiliating and one must…’

Hamed suddenly stopped when he realised how the conversation had strayed and that he hadn’t reached his original goal.

‘By the way, what is the latest news?’ he asked. ‘Has Salama still not appeared?’

‘You’re asking me about what has appeared and what hasn’t appeared, so I will tell you what has appeared,’ Sheikh Sayyid said. ‘I was standing outside the mosque last night when I saw a light shining from the direction of the village of the Salehis. A torch directed towards us. And I knew that ‘The Enemy’ was waiting for us. Ibrahim Abu Zaid, that spawn of the devil, was aiming his torch at us, and danger was looming. I sought refuge in God from the accursed Satan and went into the mosque. While I was focused on the prayer, the accursed one put out his hand and poked me in the right side of my body.’

‘But the devil lurks in the latrines and doesn’t go near the prayer area,’ Hamed said. ‘What news is there of Salama?’

‘That’s true, but he has long arms, and he stretched his hand from the latrines to hurt me. Do you not see that even though Ibrahim Abu Zaid, that spawn of the devil, lives far away from us, he still reaches us with his torch?’

Sheikh Sayyid returned to the attack. ‘I like the story of the Bedouin girl because she calls for moderation. Unlike the vulgar stories and poems you tell, Hamed.’

Sheikh Hamed was aghast. ‘Me? You slanderer,’ he said, reproachfully. ‘I tell vulgar stories and poems?’

‘I think you talk about the ghazal poets and their poetry of desire much more than is necessary, and a lot of that can corrupt the minds of the youth.’

‘True, but I tell stories about chaste love.’

‘Young people don’t know the difference between what is chaste and what is not. The youth are made of fire. Tell them stories of lovers and love poetry, and they get enflamed. What do you think will happen to the girls if words like these reach them? You are opening up doors for the devil.’

‘That is unfair!’

‘I am not being unjust towards you. What about what happened to my son Salama with the Baharwa girl? Was it not love that allowed the devil to reach them? The story begins with chaste love then ends, as you know, in the cornfield and…’

Uh-oh… now he had gone and put his foot in it by talking about Salama and his scandals. Hamed decided to ignore the charges directed at him and take advantage of the opportunity that had inadvertently presented itself, delving into the subject.

‘May God help you. Has the boy still not appeared?’

His question was never answered because when his friend reached that pointin the conversation - the cornfield - he was afflicted by a severeagitationandbegan turningleft and right.

‘I can hearfootsteps coming fromthere.’

He was pointing to the right. There were definitely footsteps, because he had seen the dust shift when he looked over. So ‘The Enemy’ had come. Here he was, crawling under the dirt, slithering like a serpent. Was last night’s harassment not enough for him? He spat on the accursed devil and hurriedly slipped on his sandals and darted off. He left without hearing Hamed’s objection. ‘Wait, man. Be patient. God is with those who are patient. The tea is on its way.’

Hamed was always trying to overtake him, but what a preposterous idea! Hamed had spent several years at the Islamic institute, whereas he had spent thirteen years at al-Azhar University. Thirteen or fourteen years? He didn’t earn a university degree, but he was the authority in jurisprudence for the villagers and the people from neighbouring villages, and he would always refer to the accredited books. What did Sheikh Hamed offer them? He knew nothing about jurisprudence. He didn’t refer to a single one of the imams’ texts, and he would speak of things he didn’t understand. All he had to offer was helping students memorize the Quran at his school (although he and his wife would exploit the pupils and ask them to do household chores, like gathering firewood, sweeping, and feeding the goat), he recited the Quran without perfecting his pronunciation, and told stories and recited poetry that distracted people from religious matters. Because of him, the boys and young men had become susceptible to corruption and were being preyed on by the devil. On the country road, he would spy them watching girls as they headed to the water. Some of them would walk along the road with their sleeves rolled up. He would advise them gently, telling them that when young men revealed their forearms, it created temptation, but none of them would ever heed his advice. And he would yell at the girls on their way to the water, because they wriggled as they walked with the buckets balanced on their heads. But he would get nothing from them but laughter and mockery. What would happen to this village whose elders turned a blind eye to this dreadful behaviour? And the worst of all the young men in the village was his own son, Salama. He had no idea about the meaning of modest dress. He would sometimes see Salama at the canal, turning the screw pump, dressed in his vest and baggy sirwal, which revealed his legs from the knees down. He would climb the palm tree without a long jilbab, and his sirwal would be the only thing covering his private parts. If anyone looked up and saw what they saw, a sin would have occurred. He had been in a panicked state ever since he saw his son watering the plants early one morning a few days ago. There was Salama, standing bare-chested, his feet sunk into the mud. This was during the time girls passed by on their way to fill up their buckets from the canal. What would happen if they were exposed to temptation? The boy never heeded his advice. His mother spoilt him, and he knew that she would always take his side and protect him in the face of any criticism. Then this scandal erupted, the news of which had spread far and wide. The people of the village consulted him on religious matters, but they hardly ever took his advice. Some of them made fun of him if his memory didn’t come to his rescue with an answer to a question, when he would have to appeal for time to refer to the writings of the scholars. They were always in a rush to solve their problems, wanting a one-word answer instead of listening to all the text, commentary, and marginal glosses, as per the fundamental teachings he had studied at al-Azhar. And they didn’t believe him when he tried to warn them about ‘The Enemy’. ‘Who is The Enemy, Sheikh Sayyid?’ they would ask him slyly. They would pretend they didn’t know who the enemy was or that he appeared in two forms, seeing as he resided in the mosque’s well and its bathing area. Although he couldn’t enter the courtyard of the mosque where the prayers were held and where the pulpit was, he had long arms. In his other form, he was personified as Ibrahim Abu Zaid from the village of the Salehis, who shone his torchlight on the village in order to see everything that was happening and to cast his evil over the victim of his choice. He must have had a hand in what happened to his son, Salama. He also told them about what he felt in his side, and what he saw when he left the mosque at night - yes, since he saw the torches locked on them - but they would just laugh. What would be the fate of this village whose people didn’t pay attention to the dangers that surrounded it?

***

Zaki walked along the main road that extended from the mosque to the country road, splitting the village in half lengthwise. Every day, it was his habit to detour to the left when he reached the country road. He’d pass the waterwheel and then, when he reached the bridge leading to the Sa’ida’s village on the opposite bank, he would walk back in the opposite direction, past Khalil’s shop, until he reached another bridge leading to the mayor’s village. During this walk, he would scrutinise the village and watch whatever was going on. But today he felt no desire to scrutinise or inspect. It was as though the reins had slipped from his hand. He noticed that Khalil’s shop was closed and his aunt Nafisa had closed her door. There was no one by the canal. He stood for a long while under the sycamore tree that shaded the waterwheel and sighed. He’d been sixteen years old when his mother had said to him: ‘My God, Zaki. You’re all grown up. You’re a man now. Why don’t you want to make your mum happy?’

‘It’s still early for marriage, Ma.’

‘What marriage, boy? Did I say anything about marriage? I’m talking about houseguests.’

‘What houseguests, Ma?’

‘Won’t you man up a bit and bring back a visitor or two to the house?’

‘We’re blessed with my father for that, Ma.’

‘What’s this got to do with your old man? Where are your guests?’

‘Are you asking me to pick up visitors from the country road?’

‘Why not? If anyone throws a greeting your way, grab hold of them and swear on your life that they’ve got to join you, then bring him to the house or to the seera. Tell him he’s welcome. Take his donkey, tether it, and bring it some fodder. Then come to your ma and tell her to “get up, Ma, and cook”. Even if this is at ten o’clock at night. That would be a happy day. If that happened, you would make me so glad, Zaki, and I would know that you’re a real man now.’

That was his first lesson in generous hospitality, and he tested his mother several times to see if she would keep to her word. She never disappointed him.

He walked back down to the village, passed three houses to the right, and reached the seera. He still cursed the day some ignorant folk decided to build their homes opposite the seera, thus shielding it from view. When he was young, it could be fully seen from the country road, as though to welcome people as they arrived. It used to be open day and night, welcoming visitors and travellers who wandered in the night and whose horses had run out of steam. How far we were from the good old days.... There was no one left who knew when the seera was built and why it was given that name, but it had been there since his childhood, and it had been there throughout the life of his father and his aunt Zainab and her husband, Hajj Mansur. It was said that it’d been built during the era of Qassim, when he and his family settled in this area and established the village. That meant the seera was as old as the village of the Qassimis, and that Qassim would only settle his family in that location if there was a place to receive visitors. The seera and the mosque were two landmarks that characterised the village and were dear to the district. The residents of the neighbouring villages would come to perform the Friday prayers and celebrate the two Eid festivals in the mosque. They’d then be hosted in the seera. And the blessed Friday would not be complete without the congregational prayer and lunch. There was no match to the seera in the district - the mayor’s headquarters itself didn’t compare - since it was a focal point for guests, strangers, and poets, both secular and religious. It was both a guesthouse and an events hall. Then, as it aged, it started to deteriorate, just as the wall of the mosque had started to crack. Look what it had come to. Who could he complain to of his ordeal? There were words deep inside him he wanted to raise to God, but they were wedged in his throat. My Lord, help us and lift your hatred and anger from us. Then he entered the seera.

***

Khalil cut through the fields towards the village of the Salehis, ‘the sons of Saleh’. He could have walked on the country road along the canal, but the country road was never quiet, even at night, and he didn’t want anyone to see him. The sky ahead lay flat and crammed with stars, buthis eyeswere focused ononly one goal: Ibrahim Abu Zaid’s house at the far edge of the village. He was a stranger who had come to the district before Khalil was born, heading straight to one corner of it, never visiting anyone nor being visited by anyone unless it was for a special purpose. The Salehis knew nothing of his family or background. But they knew, with the passing of time, that he was a drug dealer and a gang leader. Ever since he was a child, Khalil had heard that Ibrahim Abu Zaid was the one who masterminded the Nazlet Elwan incident. People said he was the one who gathered the members of the gang and delegated a role to each in the operation, while also ensuring he would emerge scot-free. When the police stormed his house and the investigation took its course,it was clear, based on definitive evidence, that theowner of the househad not left his home on the night ofthe incident. When Khalil first opened his shop, his father warned him firmly never to go to Ibrahim’s home and not to deal with him unless it was for a lawful reason. ‘The hashish and that other filth they snort is forbidden.’ Yet here he was, despite his father’s warnings, walking with his own two feet to Ibrahim to ask for help. Who else would he turn to? Where else could he seek help over what Salama had done? He had sullied the honour of Khalil’s sister and ruined her. Salama’s actions must have been calculated, relying on the fact that he was one of the Qassimis. The sons of Qassim thought they were the cream of the crop and that God had created them from a different dust from that of the Baharwa. Salama himself was poor and destitute - he had no land, cows or sheep - he earned his living as an agricultural labourer. Yet he would still strut around the village with his nose in the air because he was one of the Qassimis. How could he assault Khalil’s sister? Why didn’t she resist him? Why didn’t she call for help? Had she done that, it would have proved that he’d wanted to rape her. But whatever happened passed without any fuss. No one would have found out about it had the news not spread. Could it be that his younger sister - a shy and inexperienced girl - brought this on herself? Salama - that poor and destitute guy - must have seen that she was a Baharwa girl whose honour wasn’t worth preserving. His sight was set on Ibrahim’s house, and he only wanted one thing: revenge. If only he could reach Salama, he would drink his blood. But how could he reach him? On the way to the village of the Salehis, he stopped several times, listening for a rustling between the corn reeds. ‘Maybe a wolf or a fox,’ he said to himself. Then he carried on walking, feeling for the darkened road with his staff.

***

Ibrahim Abu Zaid was about to start the night-time esha prayer. But when his daughter ran up crying, he stopped. ‘What’s wrong, Farida?’ he asked. The girl was sobbing so intensely that she couldn’t answer. Ibrahim - the man people called a ‘murderous murderer’, and who’d say of himself that his ‘heart was hardened by the troubles hammered into it’ - couldn’t stand to see his daughter cry. He felt so sorry for the girl that his heart fluttered in his chest. His older children were grown men with moustaches. But this skinny girl, granted to him by God ‘in his old age’ from his second marriage, was the apple of his eye. ‘Come sit next to me here,’ he said. As she sobbed, Farida told him that her mother had smacked her with the broomstick because she was playing with boys. ‘Never mind, my darling,’ he said, patting the little girl’s back. He called for the mother, who argued that the girl was growing up and it was high time she stopped playing with boys. Ibrahim patched things up between the two, but he winked at his wife before she left, giving her a look that meant, ‘Don’t be so strict. The girl is still a child’. Farida wiped her tears and told him that there was a man called Khalil Abu Radi waiting for him in the reception room, which made him smile. He was pleased with himself and his accurate assumptions. Khalil, the son of the Baharwa, had come to see him. Good. He had known, ever since the news had reached him, that the Baharwa people would have to seek his help. Who else would they ask to help them stand up to the sons of Qassim? The Baharwa were a peace-loving people who only cared about business and stacking up money and arable land. They never asked God for anything but protection, and they couldn’t confront the sons of Qassim, ‘the tyrants’. No one could dispense with his services - he was the stranger, the new arrival who had come to the district from afar. Some of his youth had been spent in Palestine, where he worked as a clothes presser for the Jews in Tel Aviv, and he’d had dealings with the British camps in the Suez Canal area, sometimes selling hashish to their soldiers and other times robbing their army. When he came to this district, everyone ignored him - the sons of Saleh and the sons of Qassim equally - yet they all sought his help. They couldn’t live without him. He told Farida to ask the guest to wait until he finished the esha prayer. Just before she left, he stopped her. ‘Offer him some tea, Farida.’

He received Khalil with a hug. ‘What a pleasure. Your presence is cherished, Mister Khalil. Welcome, welcome.’ Khalil started to talk. ‘I’m coming to you, Uncle Ibrahim, to ask for a favour.’ But Ibrahim interrupted him. ‘There will be no chitchat before you drink tea,’ he insisted. ‘You can’t come here and not drink our tea. Don’t worry, you’ll get what you want, God willing.’ What is he like, this guy? Khalil thought. This gang leader - he’s such a soft touch. He swallowed the hot tea before responding. ‘Uncle Ibrahim, I’m coming to you to ask for a favour that will put me forever in your debt. That kid, Salama…’ Ibrahim interrupted him again. ‘I heard about what happened, and your request will be fulfilled, by the will of the One and Only.’ ‘It’s the girl’s honour, you know,’ Khalil said. ‘I mean, I don’t know what to say.’ Overcome by emotion, Khalil fell silent. Ibrahim patted his hand. ‘I know,’ he said. ‘I swear to God, my heart goes out to you and your father. May God take revenge against the oppressor.’ He paused, silently, for a moment. ‘Look, Khalil. Do you see my daughter, Farida? I couldn’t stand it if anyone touched a hair on her head. I know exactly what you mean.’ He gave Khalil a piercing look. ‘And your sister, Zakiya, is like my daughter.’ Khalil felt a shiver run through his body - the man was now getting to the heart of the matter. ‘I swear to God Almighty, I feel sorry for you and your father,’ Ibrahim said. ‘That righteous man who never hurt a soul. Then Salama Abu Sayyid goes and does something like that?’ Relief washed over Khalil — the man understood completely. He asked him what he thought should be done. ‘We can’t go near Zakiya,’ Ibrahim said. ‘May God take revenge against the one who hurt her. As for Salama…. As for Salama, we’ll need to deal with him in a different way.’ ‘You’re quite right, uncle Ibrahim,’ Khalil said. ‘Let us focus on Salama. But we don’t know where Salama went. He’s been hiding out for a week now, but God knows where.’ ‘Where would he go?’ Ibrahim replied. ‘He must be with his relatives. He’ll either be in Kafr Saqr or in al-Sharafa near Abu Kabir.’ ‘So how do we reach him?’ Khalil asked. Ibrahim smiled. ‘Leave that to your uncle Ibrahim.’ Khalil became quiet and looked down, worried. ‘But I’m afraid, Uncle Ibrahim,’ he said. There was still a question inside him that he didn’t dare utter. If Salama was killed in Kafr Saqr or in al-Sharafa or any other place, wouldn’t the police eventually find out who was behind the crime? Wouldn’t they be able to trace the matter straight to their front door? But Ibrahim reassured him. ‘Don’t worry about anything. We have our men in Kafr Saqr and in al-Sharafa. They’ll do everything necessary, far from you or me. A fight will erupt, one way or another, and we won’t have anything to do with it. Anyway, we’re not going to kill him. The men there will give him the beating of a lifetime and leave him crippled. And by the way, he won’t breathe a word himself about what happened to him or who beat him up. He won’t dare. Do you think what he did was trivial?’ There was a moment of silence before Ibrahim spoke again. ‘But you know, Mr. Khalil, these men…we need to please them.’ He stopped talking, but Khalil understood what he meant and put two pounds in the open palm. ‘Here’s a little something as a down payment.’ Ibrahim smiled brightly. ‘Whatever you see fit, Mr. Khalil. I would never haggle with you, I swear to God. For you, nothing is too dear to part with.’ He walked Khalil to the front door. ‘By the way, I want to tell you something about Zakiya. You should know that she hasn’t left the village.’ Khalil was stunned. ‘How do you know that?’ he asked. ‘Where would a girl like that go?’ Ibrahim told him. ‘To the Sa’ida people? Really?’ ‘Okay, so where in the village?’ Khalil asked. ‘Whose house is she hiding at?’ ‘God knows,’ Ibrahim replied. ‘But she must be at one of the Qassimi homes.’ Khalil was left speechless. After that, he didn’t utter a single word.

On the way home, it felt as though his head would explode with worry. Gone was the comfort he had felt when he first heard Ibrahim’s solution, about how Salama would receive the revenge he deserved, yet no blame would fall on him or his father. Ibrahim had unwittingly destroyed this sense of reassurance when he guessed - and it seemed he must be right - that Zakiya had not left the village. Which of the Qassimi homes could she be hiding at? He couldn’t exactly go and inspect the houses of the Qassimi one by one in search of her. He didn’t want to do that, and in any case he didn’t want to find her. Finding her would be a huge disaster. What could he do with her, or for her? It would be better if she left and disappeared forever, without a trace. Salama could go to hell, but Zakiya? If she wasn’t killed, what would they be able to do for her? No suitor would approach her, and no one would come near her. She would be disgraced...worse than a spinster, divorcee, or widow. Could she be locked up in the house so no one outside could see her? He had thought - and so had his parents - that she had run away, left the village completely. There was a solution in that - a kind of solution at least - to the problem. Until Ibrahim Abu Zaid, that cunning fox, had pointed out that she was hiding somewhere in the village. Khalil tapped on the ground with his staff. In this case, breaking Salama’s bones would not be the end of the torment. He had defiled Khalil’s sister, his own flesh and blood, and ruined her forever. Whenever the unbearable notion of his sister’s fall from grace seized him, he wished he had insisted Ibrahim Abu Zaid kill the cowardly rascal.

***

Salama’s heart pounded when he recognized Khalil Abu Radi in the dark. Salama was on his way back from his hiding place at his relatives’ in Kafr Saqr, and he’d decided to take this roundabout route to his village, sneaking between the fields of the Salehis. But the Lord willed that he would end up bumping into Khalil right where he didn’t expect to see him. Why was Khalil going to the village of the Salehis and taking this route in the dark of night? It was by chance that he had spotted Khalil from afar and had sunk down near the canal. If he’d hesitated for one moment, Khalil would have seen him, and he would have suffered the consequences. His heart raced when Khalil stopped. He must’ve heard him shuffling between the cotton reeds. Salama waited for a long time, crouched in his hiding place, holding his breath until he was sure that Khalil had moved far enough away. Now all that was left was to reach his village - and specifically the seera - without anyone seeing him. He didn’t want anyone from his family to see him before he met his uncle Zaki in the seera. He needed to pass by Zaki first, before anything else. His uncle Zaki was the only one who could protect him, and he had to accept his judgment and punishment, whatever it would be. If he could get Zaki on his side, then it would be easier to convince everyone else, including Khalil, his father, and the rest of the Baharwa clan. He could face everyone if Zaki supported him. When he reached the seera, he found Sheikh Zaki with his head buried between his arms and knees. He didn’t notice the greeting that was called out to him. It seemed to Salama that his uncle was asleep, but in fact he was deep in thought.

Visitors and strangers would dismount from their horses before going down to the village, greeting anyone they found near the waterwheel. They might ask who the people of the village were, and they would be told, ‘The Qassimis’. They would ask about the village chief, and they would be told, ‘Hajj Zaki’, to which they would reply, ‘a blessed and gracious honour’. Whomever they found near the waterwheel - man or child - would accompany them to the seera