6,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Open Book Publishers

- Sprache: Englisch

In this rich memoir, the first of two volumes, Paul Farmer traces the story of A39, the Cornish political theatre group he co-founded and ran from the mid-1980s to the early 1990s. Farmer offers a unique insight into A39’s creation, operation, and artistic practice during a period of convulsive political and social change.

The reader is plunged into the national miners’ strike and the collapse of Cornish tin mining, the impact of Thatcherism and ‘Reaganomics’, and the experience of touring Germany on the brink of reunification, alongside the influence on A39 of writers Bertolt Brecht, John McGrath and Keith Johnstone. Farmer, a former bus driver turned artistic director, details the theatre group’s inception and development as it fought to break down social barriers, attract audiences, and survive with little more than a beaten-up Renault 12, a photocopier and two second-hand stage lights at its disposal: the book traces the progress from these raw materials to the development of an integrated community theatre practice for Cornwall.

Farmer’s candour and humour enliven this unique insight into 1980s theatre and politics. It will appeal to anyone with an interest in theatre history, life in Cornwall, and the relationship between performance and society during a turbulent era.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Ähnliche

AFTER THE MINERS’ STRIKE

After the Miners’ Strike

A39 and Cornish Political Theatre versus Thatcher’s Britain

Volume 1

Paul Farmer

https://www.openbookpublishers.com

©2023 Paul Farmer. @2023 Rebecca Hillman (Preface). @2023 Mark Kilburn (‘Plays’ section)

This work is licensed under an Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International (CC BY-NC 4.0). This license allows you to share, copy, distribute and transmit the text; to adapt the text for non-commercial purposes of the text providing attribution is made to the authors (but not in any way that suggests that they endorse you or your use of the work). Attribution should include the following information:

Paul Farmer, After the Miners’ Strike: A39 and Cornish Political Theatre versus Thatcher’s Britain. Volume 1. Cambridge, UK: Open Book Publishers, 2023, https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0329

Copyright and permissions for the reuse of this image is provided in the caption and in the list of illustrations. Every effort has been made to identify and contact copyright holders and any omission or error will be corrected if notification is made to the publisher.

Further details about the CC BY-NC license are available at http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/

All external links were active at the time of publication unless otherwise stated and have been archived via the Internet Archive Wayback Machine at https://archive.org/web

Digital material and resources associated with this volume are available at https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0329#resources

ISBN Paperback: 978-1-80064-912-5

ISBN Hardback: 978-1-80064-913-2

ISBN Digital (PDF): 978-1-80064-914-9

ISBN Digital ebook (EPUB): 978-1-80064-915-6

ISBN XML: 978-1-80064-917-0

ISBN HTML: 978-1-80064-918-7

DOI: 10.11647/OBP.0329

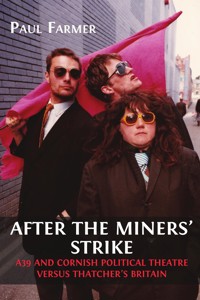

Cover image: A39 in street theatre mode at Camborne Trevithick Day, 1985

Cover design: Jeevanjot Kaur Nagpal

This book is dedicated to the memory of our friend George Jackson Greene, 1953–2022; and to Shirley Kathleen Allen, 1933–2023.

Table of Contents

Authors’ Biographies ix

Acknowledgements xi

Preface 1

Rebecca Hillman

Introduction 7

1. A Tour through the Miners’ Strike 11

2. Into A39 27

3. One & All! 37

4. Street Theatre and Cabaret 61

5. Touring One & All! 67

6. A39 International 83

7. A39 and the Tin Crisis 91

8. A39 Into 1986: The State of Things 95

9. Building the New Show 105

10. ‘How much easier it is to honour the dead than to value the living’—The Tale of Trevithick’s Tower 119

Plays 135

11. One & All! An unofficial history of Cornish tin mining 137

Paul Farmer and Mark Kilburn

12. The Tale of Trevithick’s Tower 183

Paul Farmer and Mark Kilburn

Bibliography 251

Index 257

Authors’ Biographies

Paul Farmer first worked in Cornish arts as an actor/musician/bus driver with Miracle Theatre, then co-founded A39 Theatre Group, later becoming artistic director. As a freelance playwright he wrote a number of plays for Kneehigh Theatre Company and for Cornish community events and celebrations. During the mid-late 1990s Farmer was one of those who established the Cornish film industry, as a writer, director and producer. An increasingly experimental film practice would lead to a number of projects exploring digital image work in a literary context.

He was a founder member and company manager of the live literature collective Scavel An Gow, then one of the three artists who represented Cornwall in the European Regions of Culture initiative, leading into work in a fine art context in performance, moving image and installation.

He holds an Honours degree in Theatre from Dartington College of Arts and a Masters in Fine Art: contemporary practice from University College Falmouth. From 2014 to 2022 he was a lecturer in film and theatre at Falmouth University. In 2000 he was made a Bard of Gorsedh Kernow ‘for services to Cornish arts’.

Rebecca Hillman’s work as Senior Lecturer in the Department of Communications, Drama and Film at the University of Exeter is informed by her involvement with trade unions and political campaign groups. She enjoys teaching her module Activism and Performance to examine with students how social and industrial movements use performance and other cultural forms to make change in the world. Her recent publications explore theatre as a political organising tool, working-class theatre, housing and activism, and collaborative efforts to strengthen links between artists and the labour movement. Rebecca is the Principle Investigator on the AHRC Fellowship Performing Resistance: Theatre and Performance in 21st Century Workers’ Movements. She is writing a book based on some of this work, to be published with Bloomsbury in 2025.

Mark Kilburn was born in Birmingham and lived for a number of years in Scandinavia. Between 1996–98 he was writer in residence at the City Open Theatre, Århus, Denmark, and in 2002 he was awarded a Canongate prize for new fiction. In 2012 he won the ABCtales poetry competition. Subsequent prizes include first place in the Cerasus Poetry Olympics, 2020.

His first novel, Hawk Island, was originally published by ElectronPress (currently out of print). His poetry collection, Beautiful Fish, is available from Amazon (print) and Cerasus Poetry (digital). His latest novel, The Castle, set in Falmouth during the English Civil Wars, is available from Amazon in paperback, hardback, and digital editions.

Acknowledgements

Grateful thanks to Sue Farmer, Lucy Kempton and Mark Kilburn for being great comrades and colleagues in these adventures; and to Sue and Mark for their help in making this book happen.

My gratitude too to Tim and Mary Fowler for their help and permission to include George J. Greene’s photos; and to Bill Scott for the McBeth photo and for inadvertently kicking the whole thing off!

Alessandra Tosi and all at Open Book Publishers have been an absolute pleasure to work with, and many thanks too to Dr Rebecca Hillman, both for her wonderful Preface and for her enthusiasm for the work.

Above all, my gratitude goes out to Amanda Whittington-Walsh for all her everyday support while I’ve been writing this, and for everything else too.

Preface

Rebecca Hillman

© 2023 Rebecca Hillman, CC BY-NC 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0329.01

‘Busking in a twilight zone of performance’

Three quarters of the way through the last century, a rich seam of enquiry emerged that explored how theatre was harnessed to achieve political goals for the working class. For some time, documenting this work was itself considered an intervention, and part of a broad effort to advance the international cause of socialism. However, the ascent of neoliberal capitalism in the years that followed not only weakened organising capacity and the industrial bases that historically supported lively ecosystems of radical art, but also the cultural frameworks that had sustained them. Cultural and analytical frameworks were eroded further by disillusionment with twentieth-century regimes, common perceptions of the organised left as having failed, and wariness—especially in the academy—of art as an advocate of political ‘truth’.

So profoundly was this shift reflected in theatre studies and in the emerging field of performance studies, that scholars questioned whether the category of ‘political theatre’ any longer made much sense, ‘except, perhaps, as an historical construct’ (Kershaw 1997).

Yet while it is true that the British labour movement and accompanying praxis went into decline at this time, this narrative does not tell the whole story. It leaves workers’ theatre hanging at the end of the 1970s despite its endurance in the following years, and despite an increase in class-conscious and materialist critiques from artists and theatre makers that has helped sustain new socialist movements over the last decade, in the UK and elsewhere (Filewod & Watt 2001, Hillman 2022a).

It also misses the work of companies like A39: a homegrown agitprop troupe who told the story of Cornish mining in the context of the struggle that was ‘currently embodied in the civil war in the coalfields’ (Farmer 2023: 24). A39 were formed with the explicit intention of raising support for those engaged in one of the largest and longest industrial actions anywhere on record, when coal workers in Britain went on strike to prevent pit and colliery closures between 1984–1985.

Despite the urgency of that context, the decline in interest or confidence in left movements and culture is the backdrop for Farmer’s reflections in this book that A39 ‘operated in the dying years of an artistic era’ (117). As he saw it, diminishing hope in the academy as to ‘whether political theatre was even possible’ contributed, ironically—tragically, really—to the closing-down of progressive praxis by some of ‘its primary beneficiaries’ (118).

Yet by Farmer’s own admission these doubts, even his own, alsofall short of the full picture. He describes political theatre workers responding to academics ‘in bewilderment’ at a conference in 1990, when they kept returning to the question of ‘whether political theatre was even possible’. ‘Of course it was possible’, the theatre workers declared, ‘we did it on a daily basis!’ (117). Rather than having withered away, these ‘unlikely artists’ had taken root in the rich soil of the preceding years (118).

At a basic level, Farmer’s book records political agitprop theatre that took place at a time often regarded as having gone without. This, as well as A39’s struggle for funding, are reasons to suggest that what has been missing since the 1980s is not the art but its practical support and understanding.

Farmer’s provocative, very readable book is the first to document the practices of A39, and one of the only existing accounts of political theatre in Cornwall. Such a record is precious in and of itself, for its contribution to the history of socialist and working-class theatre. Because of this, it is also an important response to the situation described above. Although it does not position itself as a political analysis of culture or the theatre industry, threading through the chapters are arguments on class, marginalisation, aesthetics, and efficacy, that command attention.

After the Miners’ Strike: A39 and Cornish Political Theatre versus Thatcher’s Britain demands we look again at any neat timeline where history, politics, or agitprop theatre come to a halt, or even enter a twilight zone. By telling A39’s story in terms that are as charged and unapologetic as the theatre he documents, and by refocussing attention to local experience, where ‘nothing had changed in our communities’, Farmer’s account directly addresses the exclusion—at least between 1984–1992—of regional, working-class political culture in England (117).

The fact the work of A39 is only now receiving critical attention is perhaps a further indication of this exclusion. It’s also an exciting prospect, though. That is, if I am an historian who specialises in workers’ theatre, who also happens to live around the corner from Cornwall — and I’ve only just heard about A39 — what other theatre of this ilk is yet to emerge from the woodwork?

‘Agitprop as a badge of honour’

A39 followed in the footsteps of political theatre practitioners in England and Scotland in the decades immediately prior to their formation, particularly the work of 7:84. They were also influenced by European political theatre of the mid twentieth century, especially the theories of Bertolt Brecht. Farmer discusses how A39 aimed to make a powerful, personal connection with their target audiences through popular forms and aesthetics. For example, by operating ‘in spaces usually entirely dominated by loud music’, their shows would start and end ‘like a gig’ to enable the kind of ‘[moments] of intense possibility’ Farmer associates with music concerts (68). He explains how such approaches helped them produce class-based analysis in a way that engaged local working-class audiences, who lived through the theatrical experience with the company rather than just bearing witness (58).

He also explains how, rather than being put off by political theatre traditions associated with the organised left, A39 found strength and resource in them. Their first show One & All — An unofficial history of tin mining in Cornwall ‘delightedly clasped’ to agitprop traditions, demanding ‘capitalists in top hats’ and ‘workers with clenched fists’ in an ‘avowedly didactic’ conveyance of large quantities of information (62). Farmer describes A39’s approach as ‘a political cell that operated as a theatre company’ and declares the company ‘embraced the label “agitprop” as a badge of honour’ (Farmer 2023: 7).

Farmer roughly measures A39’s agency for agitating audiences over ideological and industrial issues by the extent to which they managed to have ‘an effect on the world beyond the theatre,’ or rather ‘beyond the village hall, the pub or the open air’ (55). He recalls how audiences were moved by the shows, including miners and their families; the moment when district councillors became keen to engage in discussion, and the company’s ‘shock’ on realising their radical arguments could not only be made but also valued within mainstream discourse locally (Farmer 2022: 3).

His account also explains how A39, originally formed by joining forces with an unemployed workers’ collective, later found themselves at the centre of several political networks. They exercised influence within the Cornwall Theatre Alliance and extended it, acting as a bridge between various likeminded organisations and encouraging further collaboration with the Claimants Union and the Workers Educational Association, as well as members of Cornish labour parties and trades unions (ibid; Farmer 2023: 67). The later-established Cornwall Theatre Umbrella, with statutory links to Cornwall County Council and South West Arts, also came about as a result of an A39 initiative. This resonates with accounts of British political theatre in in the late 1960s and 1970s, when an ecosystem of theatre companies, writers’ guilds, claimants’ unions, and trade unions, many of which remain active today, collaborated to support one another and strengthen the cultural arm of the labour movement (Hillman 2022b). Farmer describes the ‘hinterland of community engagement’ surrounding A39 as essential for the group’s survival, reach, and impact (Farmer 2023: 67).

‘The history of a place remains in the land beneath our feet’

In-between-spaces, hinterlands, and wastelands also figure as sites of transformation and exchange in Farmer’s narrative. He describes walking near arsenic heaps and abandoned shafts of old tin mines and the influence of this on A39 plays. He mentions the distance between A39 and Southwest arts, the regional arm of the Arts Council of Great Britain, as geographically one hundred miles away, but ‘in more abstract ways [much] further’ (55). A39 counted neither themselves nor Cornwall as part of English cultural heritage (ibid). Company members are depicted as outsiders who operated apart from ‘their elders, betters, social superiors, teachers, pundits, politicians, the successful in whatever sphere…’. They would ‘literally [pick] up coins discarded by official culture’ (24, 60).

In After the Miners’ Strike,place is displaced and contested, damaged or inaccessible. It is also embraced as something we belong to and that belongs to us. A39 is named after the road connecting its members in Truro and Falmouth. Although not all company members were born and bred in Cornwall, their shows were based on living there and engaging deeply with the people, the land, the past, and possible futures. They were deeply committed to honouring and animating Cornish history and its connection with ongoing workers’ struggle. Through this endeavour they forged new bonds and bridges, binding people together across place and time.

The tradition of connecting history and place is often fundamental to political theatre, and characterised creative approaches to political protest throughout the 1990s and into the 2000s. It is also upheld in the work of political theatre companies active today, for example Red Ladder’s tour into old mining communities with the show We’re Not Going Back (2015), Common Wealth’s We’re Still Here produced in collaboration with Port Talbot’s ‘Save Our Steel’ campaign (2017), or Salford Community Theatre’s Love on the Dole (2016) and The Salford Docker (2019).

The other day, I spoke to a student at the University of Manchester who is interested in working-class, political, site-sensitive theatre. Inspired by 7:84, Salford Community Theatre, In Good Company, and others, she told me she wants to make theatre to assist positive change in her community when she graduates. After the Miners’ Strike… will be an invaluable resource and inspiration for this young woman, as it will be for others who reach for theatre as a process of socialism and a tool to improve the conditions of those who work to live.

References

Farmer, Paul, Unpublished book proposal for Open Book Publishers Applied Theatre Praxis Series (2022).

― After the Miners’ Strike: A39 and Cornish Political Theatre versus Thatcher’s Britain, vol. 1 (Cambridge: Open Book Publishers, 2023), https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0329

Filewod, Alan and David Watt, Workers’ Playtime: Theatre and the Labour Movement Since 1970 (Redfern: Currency Press 2001).

Hillman, Rebecca, ‘The Red Flag and Other Signs: Reconstructing Socialist Identity in Protest as Performance’, European Journal of Theatre and Performance, 4 (2022a).

― ‘Art for the Labour Movement and Everyday Acts of Political Culture’, in Critical Pedagogy and Emancipation: A Festschrift in Memory of Joyce Canaan, ed. by Stephen Cowden, Gordon Asher, Shirin Housee, and Maisuria Alpesh (Bern: Peter Lang 2022b).

Kershaw, Baz, ‘Fighting in the Streets: Dramaturgies of Popular Protest 1968–1989’, New Theatre Quarterly,13.51 (1997).

Introduction

© 2023 Paul Farmer, CC BY-NC 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0329.02

This is the first volume of the story of a tiny theatre company in a distant part of the UK that operated like a political cell; or alternatively, of a political cell that operated as a theatre company.

A39 Theatre Group came into being because of the great Miners’ Strike of 1984–85. It embraced the label ‘agitprop’ as a badge of honour. A39 was motivated entirely by ideology and operated within a methodology and aesthetics conditioned by the countercultural movements of the 1960s–80s. Its reference points were identified as those that could best facilitate participation in the political struggle. The members of A39 wanted to fight for their class against the government of Margaret Thatcher. That this fight took the form of theatre at all was simply because that was where the members’ common experience lay, and because theatre was the medium they believed could best resist the Thatcherite forces of hegemonic capitalism.

The theatre practice that resulted was immediate, often comedic and, conducted with little access to funding other than that generated by income, was through both commitment and necessity widely accessible. Image and aesthetics meant that significant aspects of the practice could comfortably operate in spaces usually entirely dominated by loud music or, on the other hand, by the most abrasive of performance poets.

This book will locate the theatre practice in the context of the political, cultural, and artistic circumstances that could be seen as its parameters, and of the circumstances that brought it into being. The Miners’ Strike was defeated, which allowed Britain in the longer term to become the country it is today: one of widening social divisions and economic disparities with permanent unaddressed crises in public issues such as health and housing. It might be described as a society that hates itself, with its various parts each either despising or resenting (or both) the others for reasons it denies its subjects, for ideological reasons, the tools to understand. It was the Thatcher era that birthed this monster, enacting a huge change in the outlook of Britain that, with the aid of the Reagan regime in the USA, managed to export then globalise itself. It marked the transition from the expectation and political demand that lives and circumstances should improve, that technology would render the future better than the present, that lives would be longer, that there would be less hunger, and that people would be healthier and happier, to a vision of decline, disengagement, and ever-worsening poverty and hopelessness in which governments and mass media overtly exploit racism and division to maintain a steady state of power.

Part of that huge change has been the end of the countercultural artistic practices and communities that formed an aspect of A39’s birth context, as they did for other political theatre practices such as Joint Stock, Red Ladder, Banner, as well as 7:84—founded by John McGrath whose book A Good Night Out is cited here.1 So the study of A39 also provides an insight into an era of fundamental interaction between the arts and the political New Left that was taken for granted at the time but is now a novelty, though subsequent generations of ‘satirical’ comedians (an area in which A39 came also to operate) continue to wear its accoutrements without accepting or even understanding any of its aims or responsibilities.

There are other useful historical facets of this memoir. A39 managed to demonstrate that its politics had applications relevant to the community and cultural issues of Cornwall. There is a picture here of the host community that is recognisably different from its currently perceived nature. And it is a historical document in terms of the mediation of political argument and wider issues of communication technology. This is an arts practice in a form chosen because it was accessible without capitalisation or access to mass broadcast or distribution. It was formulated to be not only local but personalcommunication, so theatre was chosen in preference to any kind of screened medium. Around us were stirring already the early facets of the ‘Third Disruption’, which would transform the issues of this choice and render possible forms that are accessible both to small groups without the intervention of capitalised structures, and also to large audiences in cases where they can be engaged. But at the same time, social media and its exploitation in terms of advertising and political campaigning has altered knowledge and pedagogy such that propaganda looks thoroughly respectable in comparison.

This book, together with its second volume, describes a moment in the history of theatre, or maybe just the end of a moment. But in this, it also reflects both a wider cultural blossoming and its curtailment. Britain’s political theatre has been a victim of the ongoing class war in the same way as its manufacturing industry, its welfare state, and its communities, killed off in the interests of profit for a few for whom nothing is too valuable to be sacrificed to their own ever-growing wealth.2 The history of Britain in the decades since the events described here demonstrates the rightness of the arguments made by Britain’s mining communities during the great strike of 1984/85; arguments which A39 was created to disseminate.

1 John McGrath, A Good Night Out — Popular Theatre: Audience, Class and Form (London: Nick Hern Books 1996). The history of the formation of this phase of British political theatre was detailed in Catherine Itzin, Stages in the Revolution: Political Theatre in Britain Since 1968 (London: Eyre Methuen 1980).

2 For a summary of factors in the demise of British political theatre reviewed at the time of McGrath’s death, see Brian Logan, ‘What did you do in the class war, Daddy?’,The Guardian, 15 May 2002, https://www.theguardian.com/culture/2002/may/15/artsfeatures.

1. A Tour Through the Miners’ Strike

© 2023 Paul Farmer, CC BY-NC 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0329.03

My professional arts career began because I had been a bus driver. Miracle Theatre, in my new home of Cornwall, was buying a bus and needed someone who could make it go. The Bedford single-decker was a horrible thing. I was taken to London as adviser in its purchase from the London Transport garage at Catford, sleeping overnight in a Renault 4 parked up at Crystal Palace. After a test drive, I tendered my best advice — ‘Don’t buy it!’. They bought it.

A career spent in ten thousand GLC school runs on the flat roads and short hills of London, saved from any urge to speed by the density of traffic, had enabled it to survive the fact that the bus’s vacuum brakes were one of the world’s fictions. As its custodian and operator, I’d have been better off with an anchor to chuck out of the window of the cab I shared with its stinking three-litre petrol engine, which had the guts of a jellyfish or the most shrinking of Rodentia. The more sentimental elements of the theatre company immediately gave this shaking, dangerous behemoth a name, but I do not even remember what it was. I, who had to drive and maintain the thing, felt no bond with it. It was my burden.

Sometimes, when hurtling down a Cornish hillside, the bus would jump out of gear, leaving me with no control whatever of this overloaded red box save a handbrake that operated by locking clenched metal hands around the drive shaft. I never tried this at speed, certain that its first use would also be the last as all the innards of the bus junked themselves along the road, sliding along on the film of oil the bus customarily trailed like a tail. In pursuit of branding and free publicity, the beast was plastered with signwriting and company posters. Inscrutable anonymity would have been a far better friend. It undoubtedly made us many enemies amongst the thousands of drivers forced to breathe the particulates of its wake for slow unpassable miles as it crawled over the face of Cornwall and England with the name ‘Miracle Theatre’ blatantly claiming the blame.

Through the winter of 1983–84 we rehearsed in a barn in the rough land of the mining area west of Truro. Bill and Coral Scott’s house at Fentongoose, with its outbuildings and mobile homes enclosing a yard and small community that reminded me of the back cover of Gong’s Camembert Electrique, was a long way from any road. The company I joined was Bill, Rem (Rosemary) Drew, Chris Humphries, Mary Humphries (who would be forced for family reasons to quit the tour at an early stage), Steve Clarke, and Sue Farmer. Maggie Bull was costumier, and on tour we would be joined by her daughter Vicki and Vicki’s boyfriend John, whose blue hair I remember but not his surname. Bert Biscoe was musician and arranger. I could play guitar and bass and assorted other things, so my first and almost immediate promotion was to the pit band.

Through the short days and long nights we rehearsed our two shows, then bounced our various disintegrating vehicles (though not, thankfully, the bus) dangerously down a dirt road for last orders in the pubs of Truro. 1984 was hoped to be a breakthrough year for Miracle Theatre. As well as the godforsaken bus there was to be a huge yellow pyramid tent for the bus to carry, with triangular aluminium structures for legs, so tall it must be erected with a scaffold tower; and that must be carried too, and seats to fill this huge theatre, and equipment to cater for a large company, and lights and sound equipment. The bus was not only full to bursting but gear was piled on top as well, as high as a double decker. For as long as I was out on the road, all this materiel was my responsibility.

On 25 May 1984, the tour began. We erected the tent in Trelissick Gardens near Feock, four miles from our Fentongoose headquarters. It was exhausting and it took hours. And it rained. The heavy yellow canvas held the water in its folds and crawled up its frame like a slug as we hauled on the tackle. It was cold, and the moist wind assailed us from the Carrick Roads. This first set-up took far longer that it should and the audience was forced to wait in the rain for us to finish, but this wasn’t as serious a problem as it might have been because there were only a handful of them. I wanted to be at Carlyon Bay where The Psychedelic Furs were playing the Cornwall Colosseum. Instead, I was breaching my principle of never performing to an audience that is smaller than the cast, because now I was also in the shows. Why not? I was there anyway. This is the artist’s version of Mission Creep.

The tour slowly gained momentum. We performed the two plays we had worked on through the winter. In the afternoons we did The Joke Machine, a show aimed at children. Sue Farmer starred as ‘Susie’ in a red plastic mac, and that’s all I remember about it really, except that the plot involved a TV game show for which Bert and I played snappy theme music, him on guitar and me on bass. We didn’t really get on. In the great tradition of the pit band, we would glower at each other and everyone else while playing this jolly music, me wearing a blue beret for which I apologise. As our brusque muso cool abraded each other’s, I would come to value Bert Biscoe very highly. Nowadays he is both poet and a pillar of the Cornish community, his status as a leading musician on the Cornish scene largely forgotten. But it was very useful in our rudimentary street theatre act, based on some of the music Sue and I busked when times were hard, which they usually were. Miracle’s al fresco performances took the form of old songs like Da Doo Ron Ron and Something Good, or singalong modern material like Ronnie Lane’s How Come?, with simple little choreographies performed by Sue, Mary, Rem, Steve, and Bill with accompaniments by Bert, Chris, and I. This earned money for petrol for the bus and the vehicles that transported the rest of the company, and was also an opportunity to publicise the shows directly to the public in the Fore Streets, High Streets and precincts of Cornwall and England.

There is something raw and exposing about street performance, setting up and beginning the act to an entirely theoretical, invisible audience and watching the reality assemble itself in ones and twos and families. The direct address mode develops and personalises that aspect of the entire art which I remember hearing described (it might have been by me) as to ‘refrain from not performing’—the battleground leap of going Over the Top into enacting this thing that feels like it already exists. This may seem a grandiose description of the singing of an old Herman’s Hermits song, but all rituals require some moment of the claiming of significance both for the enactors and the receivers, and that moment is it.

In the evenings we performed McBeth, Bill Scott’s adaptation of the Scottish Play with extra bits by Middleton. I wrote some music as a setting for Middleton’s verse as an overture—pushy buggar for a company driver, wasn’t I? It was not the intention. Somewhere in my life I had learned the confidence to identify issues and sometimes to sort them out, but not when not to do that. In Miracle’s version, McBeth himself represented a real person, played by Chris Humphries. The rest of us played the witches, as dæmons who conjured up illusions and characters within which McBeth enacted his degradation and demise in some space of the imagination. I approved of this Cartesian approach. It posed interesting questions about our relationships with our own versions of reality and seemed to me to make more sense than Shakespeare’s original, in which the witches appear to wreck Macbeth’s life to pass the time, or maybe as an obsessive essentialist essay in the Tragedy form. But I always saw opportunities for development in the production and as we toured the show for all those months, I would put forward idea after idea for things we might add or subtract or remake. The show resolutely remained as it was, and I came to see this unchanging re-enactment as a frustration of our potential collective creativity and that, without profound mutual engagement to maintain them, inevitably the considerable stresses of this lifestyle would be visited on the personal relationships within the company.

This judgement was probably entirely based on observing myself. Sometimes I would arrive on site after forcing the bus brakeless to another destination, nerves jangling and back aching, perhaps after having had to change a wheel by the side of a motorway or deal with one of its many mechanical crises, and just strut away in a targetless rage. But Bill too would write of the tour that ‘by the end everyone had lost money, enthusiasm and their good humour,’ and that, of this and the subsequent production, that ‘Miracle was suffering from a lack of any direction or identity’.1

Because this tour was immense, from May to September, day by day by day with very little in the way of rest. We lived on the road—how romantic that sounds!–in tents we erected in the shadow of the huge yellow pyramid Bill had commissioned from the hippy artisans of Bath. I was already sick of our own two-person tent before we started, having lived in it for several weeks when I first arrived in Cornwall only a few months before; and now there were three of us in it: Sue, Matty the springer spaniel, and me.

Above all, this was the summer of 1984….

During the months Miracle Theatre had been rehearsing the play and organising performances, events had been developing towards the most significant industrial conflict since the General Strike of 1926: the 1984–85 Miners’ Strike. As Francis Beckett and David Hencke put it, ‘Britain before the great miners’ strike of 1984–5 and Britain after it are two fundamentally different places, and they have little in common.’2

At the beginning of March, it began, with the announcement by the National Coal Board of the impending closure of what were termed ‘uneconomic pits’.

In detailing this story, it is important to say that nearly forty years later there is little in the way of an unpartisan history available. Everybody has their angle. Its personalities and motivations are the armatures around which ideologies and prejudices cluster. But the evidence is now clear that the announcement of the planned closures was a deliberate provocation intended by Thatcher’s government to precipitate a strike. It turned out that the inclusion in the list of Cortonwood in the Yorkshire coalfield was a mistake,3 but it was here the miners first walked out in protest, and on 6 March 1984 their strike was made official by the National Union of Mineworkers.4 Other mines and Regions of the NUM joined the dispute regarding the threatened closures, and on 12March the strike was declared national.5

There had already been an overtime ban in place since the previous autumn, but the Conservatives’ plans to provoke such a nationwide confrontation with the miners’ union had been laid and unfolded over a period not of months but of years. It was significantly an act of revenge. In 1972 the miners defeated the Conservative government of Edward Heath in a pay dispute, and their victory historically focused on a mass demonstration that included supporters from other industries—organised by a little-known activist called Arthur Scargill—that closed down the fuel storage depot at Saltley in Birmingham in what became known as the Battle of Saltley Gate.6 The terms of Heath’s climbdown elevated the miners to the top of the industrial wage scales and led to a general perception of the NUM as leading the Trade Union movement, in terms of industrial muscle and political credibility.7

Then, in early 1974, further industrial action by the miners caused Heath to declare the Three-Day Week, limiting the amount of time companies, factories, and premises could open to pursue their business, and then to call a General Election over the question ‘Who Rules Britain?’. The electorate’s answer was ‘Not you mate!’, and the Tories were removed from power for more than five years. The wing of the Conservative Party that was moving ever further to the political right swore this should not happen again and began fulminating revenge and redress against the miners and their union.8

In the election for Conservative leader in 1975, Margaret Thatcher defeated Edward Heath and all comers to become the first woman leader of any British political party,9 and she and her fellow travellers—those she would label as ‘One of Us’ (she habitually spoke in capitalised words) and that Jonathon Green has described as ’her court of cowed sycophants’—set about rationalising their hatred of the NUM as part of a plan to end nationalised industries and the existence of trades unions as a significant factor in British economic life.10 Reports by her business courtier John Hoskyns and urgent parliamentary acolyte Nicholas Ridley, Conservative MP for Cirencester and Tewkesbury, were strategies in how to overcome these, both as enemies of Thatcherism and as affronts to her values and vision.11

Now, the use of ‘flying pickets’–a mobile force of strikers that could appear wherever they were needed to persuade or shame a workforce into joining the strike, the strategy pioneered by Arthur Scargill in 1972–was effective in the early days of the great strike. So recommendations from the secret annexe of the Ridley Report were put into effect and a national police force was created as a weapon of the government to negate the pickets, with roadblocks to prevent movement and brute force to greet them where they arrived.12 Arthur Wakefield, a striking miner from Frickley Colliery in Yorkshire, described in his diary an attempt to drive to another mine:

Day 32: Wednesday, 11 April 1984 We are going to a pit called Gedlin. We were to take the M1 and go to junction 27 [but] the police were waiting for us; they took Tony’s name and registration number and told him not go any further or he would be arrested. We were kept waiting for a while then told to go back the way we had come, so we had no alternative. Wednesday was short and sweet but better luck next time.

13

Where the pickets did arrive, they were greeted ruthlessly:

Day 46:…. They made their move by putting the pressure on. We dug our heels in and linked our arms and it seemed as though we were holding our own when all of a sudden they broke the barrier, and it was a free for all. The police from the Met pushed and kicked and told us in no uncertain terms to take off. There were several ugly scenes. We were pushed out of the pit lane onto the main road and across the other side of the road from the pit gates.

14

This, then, was the country through which I drove the Miracle Theatre bus, unable to ignore this seminal struggle. The Conservative Party, the police, and the national press coalesced with every appalling barroom bore to form an easily identifiable Bad Guy; and the strike progressively exposed hypocrisy in what purported to be the leadership of the Labour Movement, reaffirming its institutional history as a catalogue of disappointments. Though there was sincere support from some trade union leaders, much solidarity action collapsed or was called off; the NUM leadership was condemned by Labour Party leaders and the Trade Union Congress (and by many a charlatan since) on the technicality that there had been no national ballot on the strike, though clearly if that ‘justification’ had not existed they would simply have sought another. The miners’ long-standing practice was that it should not be possible for miners of one region to abandon the interests of another when others’ jobs were threatened but your own was not.

In an increasingly polarised country, the traditional socialist question ‘Which side are you on?’ was not difficult to answer. In his paper ‘What Is It Like to Be a Bat?’, philosopher of mind Thomas Nagel says consciousness is present whenever there is ‘something it is like to be’ the entity under discussion. What it was like to be a striking miner was to be steered by your pride in your history and your union to fight for your community, a system of values, a politics of fairness, and social justice, and to do so collectively. As they picketed and marched and confronted the paramilitary police force they sang ‘Here we go, here we go, here we go!’, a collectivist chant that rings down the ages: all we have to do is quote it and we are back in those times. To the tune of She’ll Be Coming Round the Mountain they sang ‘I’d rather be a picket than a scab’, and we would too. All good people wanted to be striking miners and not their opponents, overt or covert.15

What was it like to be those who opposed the miners, or simply failed ex officio to support them? That was like being a liar, because what such figures all had in common was a shallow pretence to want one thing while really wanting another. For Thatcher and her ministers, the aim was the destruction of political opposition while pretending to want a profitable coal industry. Neil Kinnock’s leadership of the Labour Party had begun as it would go on when he emerged from his coronation at the 1983 Party Conference onto Brighton Beach to parade before photographers, turned his back on the advancing waves, and fell over in the sea. His wish that Arthur Scargill, now president of the NUM, should be removed as a force in the country, seems to have echoed Thatcher’s.16 As Milne notes:

Scargill never played by the rules of the British trade-union game and despised the routine deal-making and bureaucratic compromises accepted as inevitable and necessary by more orthodox trade-union leaders. To many union officials, that made him a poor trade unionist and a lousy negotiator. To the Coal Board and the government, it made him alarmingly impervious to the usual accommodations. For his supporters, it was a unique advantage: here, in Scargill’s description of himself, was the ‘union leader that doesn’t sell out’.

17

The atmosphere of strike and country became ever more embittered. On the hundredth day of the strike, 18 June 1984, occurred what soon came to be known as the Battle of Orgreave, or Bloody Monday. Orgreave was a coking works in South Yorkshire and its picketing-out became a symbolic aim in the tradition of Saltley Gate in 1972. Pickets were helpfully steered by police officers to a convenient location where they could be cavalry-charged by mounted police, then chased and beaten through the village streets. Famous photos show horrible police violence visited on the community, and even some of the press, by the forces that claimed to represent Law and Order, prearranged as an exemplary show of force. In another clarifying moment in terms of the resources deployed against the miners, the BBC—for its evening news—edited their footage to reorder events to suggest the miners mounted an unprovoked attack with stones and that the mounted police charged in response. The BBC too was claiming one agenda while following another.18

There were mass arrests that day, and Arthur Scargill was attacked and knocked unconscious. Frickley miner Arthur Wakefield was an eyewitness:

I look across the road to see if Arthur [Scargill] is still there. He is with two or three of the lads. The ‘cavalry’ [mounted police] and ‘riot squad’ come again. It’s 11.20 am. I take a photograph of Arthur with the lads. I glance again across to where Arthur and the lads are and some of them are running. I see one of the riot squad knock Arthur down from behind. The attacker had his riot shield in a raised position. Others were chasing the lads that ran off. I ran across the road as soon as I could to give assistance. There was a big lad [Peter Stones] picking Arthur off the ground and we put him in a sitting position. He suddenly collapsed for a brief spell then sat up again, complaining about his head. I told him it was the shield.

19

The echoes of Orgreave resound down the years. The Orgreave Truth & Justice Campaign fights still for a government enquiry into a day that saw many miners charged with ‘riot’, an offence that can carry a life sentence, their trials collapsing a year later.20

The atmosphere this created in the country was that of a low-intensity civil war, with selected citizens of the state subject to an oppression by all means available to that state, all pretence of impartiality and equality in its institutions gleefully abandoned, the media aligned with the government they claimed to hold to account: portents of the country that would come to be over the decades once the miners had lost and we had lost the miners. The mass media consistently obscured the reality of an epochal struggle over ways of life and values and cultures and freedom and family and pride: the stuff of wars.

I arrived in each new site on the tour more and more believing that it was a terrible waste of life, of my life, to donate it to an illusory Shakespearean drama while the real drama was being enacted on the picket lines of the coalfields, at the coking works and the coal ports; that there was the real struggle, the struggle of the values of solidarity, socialism, and community against the horrible sneer of Thatcherism, that thing of blasted limbs and storming skies while floods and blood claimed the world. Thatcher’s brand of Conservatism was the inner world of Macbeth rendered as ideology. I found myself spending my time in a way I could not justify in the face of this conflict that was ripping the country apart.

These were my thoughts as I drove the daylight miles and the night-time hours between performance places and exhausting labour, trying to pick out the significant in the BBC’s tortured narrative on the radio in my bus cab, relieving the anger by seeking out Small Town Boy by Bronski Beat: the sound of that early summer.

And it was a good summer of long, hot days. We were young and our skins were brown, living outdoors and everlastingly moving on, a small tribe united only in the purpose of performance to the next house, making music on the next street for money for petrol for the bastard bus; trying to find some half-ounce of privacy to maintain yourself as an individual or a couple, with friendship sometimes tested to destruction in the endless endeavour. We performed at festivals, set up in municipal parks and commons, by Bristol Docks; surrounded still by the wastelands of World War Two. I remember one night staring from the waterside across acre-mounds of rubble towards a distant pool of light that was a lone-standing pub, its surrounding terraces still flat from German bombs or municipal decisions. And across that dark vacancy came the sound of a Trad jazz band.

In Bill’s version of the play, Macbeth’s soliloquy was chanted by the entire cast exceptMcBeth. One night I found myself behind the audience intoning ‘Tomorrow and tomorrow and tomorrow’, in chorus with five other voices, to an audience of a single rat perched on its owner’s shoulder. The owner was watching somebody else. I include this anecdote because, apart from a few photos, it is stories like this that are for actors all that sustains of their ephemeral nightly art; so many ancient remembered performances, real now only in this piece of writing on these white pages. Theatre: something planned, delivered, sometimes remembered, and gone. And that was our lives, as it is for all the profession. But theatre, as its traditions and its ways of life, was not enough for me. It required too much faith that anything had effectively happened other than that one person had been fleetingly present to another in seventeenth-century verse. What was I prepared to believe had been achieved? Could I take it on faith that ‘The Play’s the Thing’, that ‘The Show Must Go On’, that ‘There’s No Business Like Show Business’? I could not. I needed some real effect.

The story of the previous twenty years in the culture that nearly everyone in the company entered by affinity, rather than as one we were born into, was a curious mixture of the spiritual and the political; a culture initially of resistance that had mutated into its own parallel society in some places, for some people: ‘The Alternative Society’. It was an idea of infinite charm and ultimate disappointment, but this is not to say it was unimportant. It had for a while freed us from some conventional restraints, those that we would otherwise adopt unexamined unless consistently careful—too consistently too careful for any of us to realistically achieve alone over anything but the shortest term. The Alternative Society, the Underground, the Counterculture, had assumptions of its own, but in which the ‘straight’ icons of wealth and ambition had no acknowledged part.

My awareness of its possibilities, largely abstracted from the pages of the music press, meant I had left school free of the perceived need for a career. I lived casually in various places, took various jobs, earned some money sometimes then did something else, wandered around doing underground things, played lots of music, lived on boats, had lots and lots of hair. Hair has always been something I do very well. My engagement had always been with the political side. The spiritual aspects of the Counterculture seemed elitist, determined to draw a hierarchical line between ‘them’, the straights, and ‘us’, the enlightened ones. That judgement too often seemed to me to mirror a very ‘straight’ class hegemony, and, having taken a job on the buses temporarily to fund the restoration of the old boat that was my home, I found I did not want after all to separate myself from my ‘straight’ working class colleagues. I stayed and became an activist in the Transport and General Workers Union.

Increasingly predominant through the 1970s and into the 1980s was the assumption that anything that could be labelled spiritual was the exclusive property of the self-defining group that still considered themselves ‘alternative’. By now, that encompassed yoga, a vague idea of Buddhism, aspects of Hinduism, even crystals and aromatic oils—anything in the exotic that could be deemed transcendental, tantric, yin and yang or ‘zen’. Since by the early 1980s this came effectively to be all that was left of the Counterculture other than Travellers’ convoys, I no longer considered myself amongst the congregation. Without an Alternative, it was the issues of this society that would need to be engaged.

Eventually, that summer of 1984 began to transform into Autumn. I had now been a Cornish resident only twelve months and when I turned the bus’s blunt nose west down the A303 for the last time, for me it was still like driving away from what I knew, rather than towards it. But by now I had little love for the England in which I was born and had led my life, after its Falklands fiesta of war and Thatcher’s consequent second election victory. This rendered me rootless, baseless anywhere beyond the abstract castle of myself and my partner, my dog, and my tent—a skinny gypsy punk whose nearly every defining characteristic, bus and company and tribe, belonged to someone else.

Back in Cornwall, after the last performances in Truro, some of us unloaded the bus for the final time. I parked it up, left the key in Bill’s wholefood warehouse by the old docks at Newham, went home and no one called. And we called no one. (We didn’t have a phone.) The world of our summer had passed.

Fig. 1. The author in a Miracle Theatre street performance, Falmouth, Cornwall, Spring 1984, with Bert Biscoe in the background. Photo by George J. Greene (CC BY 4.0).

Fig. 2. Future A39 member Sue Farmer with the loaded Miracle Theatre bus on The Island at St Ives, Cornwall, July 1984, accompanied by company dogs Matty and Casper. Each of the triangular constructions on the bus roof is half of one of the legs of the pyramid theatre. Photo by the author (CC BY-NC 4.0).

Fig. 3. The Miracle bus cab and my view throughout the Strike summer of 1984, in this case of hazy Devon hills. The oily finger marks on the bulkhead are due to my (far too frequently) off-on relationship with the engine box, just visible at bottom left. Photo by the author (CC BY-NC 4.0).

Fig. 4. Erecting the pyramid theatre. The legs are assembled, the tops then raised up onto the scaffold tower where they are fixed to the (very heavy!) steel top piece. The legs are then moved inwards to raise the assembly to full height, and joined by rigging wires to make the structure secure. Then someone (in this case Bill Scott) has to go up there to finish off. Photo by the author (CC BY-NC 4.0).

Fig. 5. The bus and the erected pyramid, top removed to let out heat. The striped tent served as the box office. The theatre entrance awning is folded down. Matty, as usual, has her own project on. Photo by the author (CC BY-NC 4.0).

Fig. 6. McBeth curtain call, left to right: Bert Biscoe, Bill Scott, Steve Clarke, John, Rem Drew, Sue Farmer, Paul Farmer, Chris Humphries. Photo by kind permission of Miracle Theatre (CC BY-NC 4.0).

1 Bill Scott, ‘A Brief History of Miracle Theatre’, The Poly 2005/06. https://thepoly.org/assets/uploads/files/Poly%20Magazine%202005.pdf

2 Francis Beckett and David Hencke, ‘Preface’, in Marching to the Fault Line: The Miners’ Strike and the Battle for Industrial Britain (London: Constable, 2009).

3 Becket & Hencke, p. 47.

4 Ibid., p. 50.

5 Ibid.

6Nine Days and Saltley Gates, Jon Chadwick’s and John Hoyland’s linked documentary plays about the 1926 General Strike and the 1972 Miners’ Strike, were toured by Foco Novo in 1976. See Graham Saunders, ‘Foco Novo: The Icarus of British Small-Scale Touring Theatre’, in Reverberations Across Small-Scale British Theatre: Politics, Aesthetics and Forms, ed. by Patrick Duggan and Victor I. Ukaegbu (Intellect 2013), p. 4.

7 Seumas Milne, The Enemy Within: The Secret War Against the Miners (London: Verso, 2014), p. 7; Becket & Hencke, p. 35.

8 Ibid.

9 Mr Heath steps down as leader after 11 vote defeat by Mrs Thatcher’, The Times, 5 February 1975;

10 Hugo Young, One of Us: A Biography of Margaret Thatcher (London: Macmillan 1989), pp. 113–115; Jonathon Green, Days in the Life: Voices from the English Underground1961–71 (London: Pimlico 1998), Introduction to the Pimlico Edition.

11 Young, ibid.; Milne, p. 9; The Ridley Report (version leaked to The Economist in 1978), https://www.margaretthatcher.org/document/110795

12 Becket & Hencke, p. 59.

13 Arthur Wakefield, The Miner’s Strike: Day by Day; The Illustrated 1984–85 Diary of Yorkshire Miner Arthur Wakefield, ed. by Brian Elliott (Barnsley: Wharncliffe/Pen and Sword 2002), p. 53.

14 Ibid., p. 57.

15 Thomas Nagel, ‘What Is It Like to Be a Bat?’, The Philosophical Review, 83.4 (1974), 435–450, https://warwick.ac.uk/fac/cross_fac/iatl/study/ugmodules/humananimalstudies/lectures/32/nagel_bat.pdf.

16 See, for example, Kinnock’s 2014 contribution to The Miners’ Strike, 30 Years On conference organised by H&P Trade Union Forum and the British Universities’ Industrial Relations Association (BUIRA), https://www.historyandpolicy.org/trade-union-forum/meeting/the-miners-strike-30-years-on-conference.

17 Milne, p. 22.

18 Ibid., p. 352; Becket & Hencke, p. 99.

19 Wakefield & Elliott, p. 118.

20 The Orgreave Truth & Justice Campaign’s website can be found at https://otjc.org.uk.

2. Into A39

© 2023 Paul Farmer, CC BY-NC 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0329.04

Our careers with Miracle Theatre were over. I would have resigned, but no one was interested. I did not want to repeat that experience. It is an effective test of motivation to spend months doing something very hard. A lack of value will become apparent on waking every morning when the question will sooner or later arise: why am I doing this? If there is no specific answer for this question you are engaged in an act of faith, and when it applies to the presentation of the work of a sixteenth/seventeenth-century writer, it is a matter of national faith. Shakespeare is an established religion every bit as much as the Church of England and, it now seemed to me, performed very much the same functions—affirming an implicit set of values with Shakespeare at the top and England firmly attached as Culture’s peak: blue riband, blue-blooded, more prestigiously high-culture than even Mozart and Wagner.1

But do Shakespeare’s virtues in any way justify this? Removing the assumptions and the necessity to believe in the object of faith, and any investment as a facet of the national image, how is Shakespeare as an experience of theatre? I was sick of participating in what I saw as the blurred-eyed defence of an out-of-date misanthropist, who wrote some poetry entirely to my taste then eked it into interminable plays through tricksy padding:

DUNCAN:

This castle hath a pleasant seat; the air

Nimbly and sweetly recommends itself

Unto our gentle senses.

BANQUO

This guest of summer,

The temple-haunting martlet, does approve,

By his loved mansionry, that the heaven’s breath

Smells wooingly here: no jutty, frieze,

Buttress, nor coign of vantage, but this bird

Hath made his pendent bed and procreant cradle:

Where they most breed and haunt, I have observed,

The air is delicate.

2

Nimble and fireworky though it may be, how does this justify any claim on our time? This passage haunts me, and not in a good way. I even wrote my own version of it:

The castle sits on its arse in the grass

Amidst some shady garden.

I think it made that awful smell

Cos I heard it beg my pardon.

Often, Shakespeare’s dross simply outweighs the poetry; sometimes each negates the other into nothing. Hamlet’s soliloquy, at great length (not just the bit you know),3 seems to me to cancel itself out of meaning. Perhaps there was some staging challenge to cover at the time and there was a need for lots of words to distract (though there is nothing inherently wrong with that–many good artistic decisions are made for logistical reasons). The dialogue of the duel scene in Romeo and Juliet4 makes me feel physically sick, and Shakespeare’s jokes are never funny. Surely Will Kemp would not waste his time on such tosh but would take it away and replace it with sex and farts and falling over. If there is some overwhelming intrinsic virtue in this, it has never been apparent to me. It is certainly not unassailably self-evident. It was questionable, and therefore must be questioned: this material was nearly four hundred years old and occupied the stages of the English-speaking world to the exclusion of far too much of everything else that discussed more relevant issues, like the Miners’ Strike for example, that continued still. Distanced by centuries, I told myself after that long Shakespearean summer that if ever I found myself again in a theatre seat in front of anyone uttering the words ‘Ill met by moonlight, proud Titania’,5 I had my own permission to eviscerate myself and sod the mess for the cleaners. Shakespeare’s effective exclusion of the new and the news in the theatres of Britain was far too convenient for all the wrong people. As Gary Taylor has noted:

The important questions, the questions that matter beyond the intellectual enclosure of Shakespeare specialists, do not concern the meaning of particular words or the motives of particular characters; they concern the blunt fact of his cultural dominance. When did people decide that Shakespeare was the greatest English dramatist? The greatest English poet? The greatest writer who ever lived? Who did the deciding? What prejudices and convictions might have influenced their decision? On what evidence, by what reasoning, did they justify their verdict? How did they persuade others? How did they discredit rival claimants? And once Shakespeare’s hegemony was achieved, how was it maintained?

6