Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Polygon

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

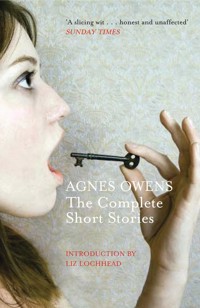

The complete life work of Agnes Owens in short stories - everything from Gentlemen of the West, Lean Tales, People Like That and 14 brand new unpublished stories. Witty and dark, Owens' spare prose shocks and delights. Her talent for pithy, unsettling tales is as sharp as ever, confirming her place as one of Scotland's finest contemporary writers.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 583

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2011

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Praise for Agnes Owens

‘Agnes Owens’ hallmarks have been a frank irony, a deadpan gothic quality and a down-to-earth insistence on the surreality of most people’s normality.’

ALI SMITH

‘I think of another literary hero, Agnes Owens. What if Agnes had been “granted” a proper chance to write when she was fighting to rear her family? . . . When she saw the squeak of a chance she grabbed it and produced those great stories we know. How much more could it have been?’

JAMES KELMAN

‘Agnes Owens is the most unfairly neglected of all living Scottish authors. I don’t know why.’

ALASDAIR GRAY

‘Agnes Owens stuns her readers, as usual, with her good, blunt-weaponed clarity in Bad Attitudes.’

THE GUARDIAN

‘Owens pulls no punches. her understated prose finds acerbic humour in the lives of characters hovering between farce and tragedy . . . Owens is a gift to the Scots urban world.’

OBSERVER

‘Owens is a gentle writer with a slicing wit . . . honest and unaffected.’

SUNDAY TIMES

‘Agnes Owens has a canny eye for tragi-comedy, a compassionate heart for the unfortunate, an acute ear for dialogue and a mind that clamps her characters like a steeltrap in the predicaments of passion, poverty and the patterns of their lives.’

FINANCIAL TIMES

‘Like all Owens’ fiction Bad Attitudes is as terse and grimly, comically deadpan as the best of Evelyn Waugh and Beryl Bainbridge.’

DAILY TELEGRAPH

‘Agnes Owens has an appealingly wicked eye for familial love on the dole . . . reminiscent of Muriel Spark.’

SUNDAY HERALD

‘These stories leave an echo. Their compassion lies in their honesty. Owens will not let us look away.’

THE HERALD on People Like That

‘A remarkable book . . . funny and sinister’

BERYL BAINBRIDGE on A Working Mother

‘Something in common with early Billy Connolly . . . in the sense that its observation and timing bring humour to a sad reality.’

NME on Like Birds in the Wilderness

‘The best things in Lean Tales are the stories of Agnes Owens . . . she creates little dramas – rich gobbets of life.’

FINANCIAL TIMES

‘Owens’s reliance on the rhythm of ordinary speech is aggressively non-literary.’

LONDON REVIEW OF BOOKS on Lean Tales

‘Strong, realistic and thoughtful’

MOIRA BURGESS

‘A remarkable and idiosyncratic voice’

THE HERALD

‘Accomplished and resonant and . . . always informed with a comic astringency’

THE SCOTSMAN on Gentlemen of the West

Agnes Owens

THE COMPLETE SHORT STORIES

Agnes Owens

This ebook edition published in 2011 by Birlinn Limited West Newington House Newington Road Edinburgh EH9 1QSwww.birlinn.co.uk

This collection first published in Great Britain in 2008 by Polygon, an imprint of Birlinn Ltd

Gentlemen of the West was first published by Polygon Books, 1984, copyright © Agnes Owens, 1984; Postscript copyright © Alasdair Gray, 1986; Lean Tales was first published by Jonathan Cape Ltd, 1985, copyright © Agnes Owens, 1985; People Like That was first published by Bloomsbury Publishing plc, 1996, copyright © Agnes Owens, 1996; The Dark Side was first published by Polygon, 2008, copyright © Agnes Owens, 2008; Introduction copyright © Liz Lochhead, 2008

The moral right of Agnes Owens to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored or transmitted in any form without the express written permission of the publisher.

ebook ISBN: 978-0-85790-140-8

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

To all those who are interested

Contents

Introduction by Liz Lochhead

Arabella (1978) This story is first because earliest written, though eventually published in Agnes Owens’ second book, Lean Tales.

GENTLEMEN OF THE WEST (1984) Thirteen stories. These were seperately written, but being episodes in one man’s life were published as chapters in a novel.

McDonald’s Dug

McDonald’s Mass

Grievous Bodily Harm

Tolworth McGee

The Auld Wife’s Fancy Man

Up Country

The Group

Paid Aff

McCluskie’s Oot

Christmas Day in the Paxton

The Aftermath

The Ghost Seeker

Goodbye Everybody

Postscript by Alasdair Gray

LEAN TALES with Alasdair Gray and James Kelman (1985) Eight stories, without Arabella.

Bus Queue

Getting Sent For

Commemoration Day

The Silver Cup

Fellow Travellers

McIntyre

We Don’t Shoot Prisoners on a Sunday

A Change of Face

PEOPLE LIKE THAT (1996) Twelve stories.

The Lighthouse

The Collectors

The Warehouse

When Shankland Comes

A Bad Influence

People Like That

The Marigold Field

Intruders

Léonie

The Hut

The Castle

Marching to the Highlands and into the Unknown 297

THE DARK SIDE (2008) Fourteen stories in a book (this one) for the first time.

Hannah Sweeny

The Writing Group

Roses

Meet the Author

Confessions of a Serial Killer

The Moneylender

The Phantom Rapist

Annie Rogerson

Visiting the Elderly

Chairles Will Pay

Don’t Call Me

Mayflies

Neighbours

The Dysfunctional Family

A Note on the Author

Introduction

I’ve just read ‘Arabella’ again. And it had exactly the same effect on me as it did the first time I read it all those years ago. From the shift in the second sentence when it had me doing a double take, it began its work of filling me with a mounting, irresistible and exhilarating black glee. It shocked, amazed and delighted me. As it has every time I’ve read it – which is quite a few times, for I have never tired of it since I encountered it on the very same night I first met its author. In, oh, 1976 or maybe 1977? Here’s how I remember that – which might not be exactly accurate, but is true to my memory at least.

‘Get in, get out, don’t linger’ is Raymond Carver’s famous good advice to the writer of short stories. This dictum would apply also to the tutor of the creative writing workshop – anything in general about writing one has to say that’s of any value at all can be said in one or two classes. I don’t know why Alasdair Gray and Jim Kelman and I were getting in, getting out, and sharing the job of tutoring that short course of evening classes in the late 1970s for beginning writers in Alexandria; was it run by the libraries, or, as I seem to remember, the extramural department of Glasgow University? I suspect, though we were certainly doing it for the money (we were all three more or less broke at the time), we still couldn’t bear to commit to a full twelve wintry weeks of 45 minutes-plus there and 45 minutes back, going down every Tuesday or Wednesday or whatever night it was by blue train from Central to this wee back room in the exotically named Alexandria. (Vale of Leven, the place next door, sounded like something out of the Psalms and Para -phrases!) Anyway, far from being Egyptian, Alexandria was actually a pretty dreich and miserable wee rain-and-windswept town in the West, so we agreed to four weeks each. Maybe the local writers had various skills to hone and had asked to have a poet and a short story writer and a novelist? At any rate, I did the first stint. At the end of the first evening, frankly, with the usual sinking feeling, I took away the wee pile of writings eagerly pressed upon me by most of the dozen or so men and women who had attended the class.

Among these was a single neatly typed piece of prose by Agnes Owens called ‘Arabella’. (Agnes was working as a typist in a local factory at the time.) It began with what I’d soon know as her typical deadpan aplomb:

Arabella pushed the pram up the steep path to her cottage. It was hard going since the four dogs inside were a considerable weight.

The four dogs. I sat up. The blue train rattled through the darkness, I read on and it was only a swift paragraph later when, taking in how Arabella had given her mother what she’d clearly meant to be a daughterly pat on the head, I learned that ‘the response was a spittle which slid down her coat like a fast-moving snail’.

In case you’ve not read it yet – it opens this collection – I’m not about to spoil your fun by giving away what happens to Daddy, or with Murgatroyd or to the Sanitary Inspector, but Flannery O’Connor herself would, I think, have approved. (You know, the great Flannery O’Connor who deplores how ‘most people seem to know what a story is till they sit down to write one’, and is keen to remind us that what they forget is that it ‘must be a complete dramatic action’.) That night on the train with ‘Arabella’, taken aback, I tried to put this terrifying, terribly funny story, so anarchic and archetypal, so short and so complete, together with the class I’d just left and that middle-aged lady in the neat coat and woolly hat with the fringe of dark blonde hair sticking out and the full mouth that turned so decisively down at the corners. A mouth she’d hardly opened except to say a couple of laconic and sensible things. (Creative writing workshops are generally very short of either sensible or brief remarks.)

I’d like to say I recognised Agnes’s genius straight away but it’s not quite true. In those days I didn’t have very much confidence in my judgements (nowadays I have too much and tend to be far too dogmatic about what I do not like) and I remember a couple of days later showing ‘Arabella’ to Alasdair Gray, saying something like, ‘Have I lost it altogether, or is this . . . I mean it’s wild . . . but isn’t it really rather good?’ I remember him reading, very quickly and sitting very still, till he’d finished, and the gleam in his eye and the wee wince around his mouth when he looked up and said very quietly: ‘Oh, yes.’

Alasdair and, a few weeks later, Jim really were the ones to help Agnes. (I remember her saying with not quite resentment but a baleful mock consternation, ‘Jim has made me take out all my adverbs.’ But I knew she knew he was right, otherwise she’d not have altered a word of it.) At the time, she was writing the stories that would eventually be published as Gentlemen of the West. Actually, I believe it was the class – she said later she only came to it because she was fed up – that made her start writing the stories about Mac and his cronies (although cronies is far too sentimental a way of putting it).

Gentlemen of the West is a kind of novel, because there is an overall progression of narrative towards a hopeful ending, the only hopeful ending – escape. I like though to enjoy these not as chapters but as discrete stories, particularly as the later ones, ‘McCluskie’s Oot’, for instance, seem to take a quantum leap and show her coming into her own, refusing to be cute anymore. They are tough and realistic in the way all her mature work is, making you open your mouth and shut it again.

At the time, I think I read these stories, the early ones at least, as a kind of downbeat and depressed West of Scotland Damon Runyon, without the dollars or the dolls. (If you read Alasdair Gray’s postscript, which is reprinted here on page 111, you’ll see I was underestimating them.) I just found them very, very funny. Bleakly, blackly funny, my favourite kind. What I greatly admired was Agnes’s nerve in ignoring the feminist imperative of the day to redress balances and dutifully record from the inside-out the female experience. Utterly convincingly, to my ears at least, she wrote with a throwaway bravura in the persona and from the point of view of a young male and it was thrilling you could do that. (Well, it wasn’t as if Mac’s voice had had much of a shot in fiction so far either.)

By the time of the publication of her first book I knew Agnes was a great and quirky original. Her sisters, if she had any at all, were . . . oh, Beryl Bainbridge, Molly Keane and Shena Mackay. But by the time I was reading ‘Bus Queue’, ‘People Like That’, ‘When Shankland Comes’, I was thinking Chekhov and Isaac Babel.

Every time I see Agnes – not often, not often enough – she seems utterly unchanged from my memory of the first time I saw her. She has had a hard life – see her rare autobiographical story (it’ll take your breath away) ‘Marching to the Highlands and into the Unknown’ – and, like the not particularly sympathetically drawn Isobel Anderson in ‘Meet the Author’ (who ‘can only write about failures’), publication for Agnes never led to her being transmuted to the ease of Artist Class. But she still looks middle-aged, not old, and her mouth still turns down humorously at the corners. Any of the quiet wee deadpan things she says are more than well worth listening to. One-to-one she is especially good company. She’d crack you up.

It is a great thing to have, at last, The Complete Short Stories. Opening with ‘Arabella’, including, hurrah, fourteen new ones in print for the first time and ending with the delicious ‘The Dysfunctional Family’. Another one. But it strikes me that if Agnes Owens has a theme it’s the functioning of families. It’s never easy . . .

Liz Lochhead February 2008

Arabella

Arabella pushed the pram up the steep path to her cottage. It was hard going since the four dogs inside were a considerable weight. She admonished one of them which was about to jump out. The dog thought better of it and sat down again. The others were sleeping, covered with her best coat, which was a mass of dog hairs; the children, as she preferred to call them, always came first with her. Most of her Social Security and the little extra she earned was spent on them. She was quite satisfied with her diet of black sweet tea and cold sliced porridge kept handy while her children dined on mince, liver and chops.

The recent call on her parents had been depressing. Loyal though she was, she had to admit they were poor company nowadays. Her bedridden father had pulled the sheet over his face when she had entered. Her mother had sat bent and tight-lipped over the fire, occasionally throwing on a lump of coal, while she tried to interest them in the latest gossip; but they never uttered a word except for the terse question ‘When are you leaving?’ – and the bunch of dandelions she had gathered was straightaway flung into the fire. Arabella had tried to make the best of things, giving her father a kiss on his lips before she left, but he was so cold he could have been dead. She had patted her mother on the head, but the response was a spittle which slid down her coat like a fast-moving snail.

Back inside her cottage she hung her hat on a peg and looked around with a certain amount of distaste. She had to admit the place was a mess compared to her mother’s bare boards, but then her mother had no children to deal with. Attempting to tidy it up she swept a pile of bones and bits of porridge lying on the floor into a pail. Then she flung the contents on to a jungle of weeds outside her door. Good manure, she thought, and didn’t she have the loveliest dandelions for miles.

‘Children,’ she called. ‘Come and get your supper.’

The dogs jumped out of the pram, stretching and yawning nervously. One dragged itself around. It was the youngest and never felt well. Arabella’s training methods were rigorous. This had been a difficult one at first, but the disobedience was soon curbed – though now it was always weak and had no appetite. The other three ate smartly with stealthy looks at Arabella. Her moods were unpredictable and often violent. However, she was tired out now from her chores and decided to rest. She lay down on top of a pile of coats on the bed, arranging her long black dress carefully – the dogs had a habit of sniffing up her clothes if given half a chance. Three dogs jumped up beside her and began to lick her face and whine. The one with no appetite abandoned its mince and crawled under the bed.

Arabella awoke with a start. Her freshened mind realised there was some matter hanging over it, to which she must give some thought. It was the letter she had received two days previously, which she could not read. Her parents had never seen the necessity for schooling and so far Arabella had managed quite well without it. Her reputation as a healer was undisputed and undiminished by the lack of education. In fact, she had a regular clientele of respectable gentlemen who called upon her from time to time to have their bodies relaxed by a special potion of cow dung, mashed snails or frogs, or whatever dead creature was handy. Strangely enough, she never had female callers. (Though once Nellie Watkins, desperate to get rid of the warts on her neck, had called on her to ask for a cure. Whatever transpired was hearsay, but the immediate outcome of it was that Nellie had poured the potion over Arabella, threatening to have her jailed. But she never did. Arabella’s power was too strong.)

The councillor’s son, who had been the caller on the evening after she received the letter, explained that it was from the Sanitary Inspector and more or less stated that if she didn’t get rid of her animals and clean her place up she would be put out of her home. Then he changed the subject since he knew it would be out of the question for Arabella to clean anything, that was one thing beyond her powers, saying, ‘Now we have had our fun get me some water – that is if you use such a commodity. I know soap is not possible.’ And while Arabella fetched the water lying handy in an empty soup tin on the sink, he took a swallow from a small bottle in his jacket pocket to pull himself together. Arabella did not like the tone of the letter. Plaintively she asked, ‘What will I do, Murgatroyd?’

‘That’s your worry,’ he replied, as he put on his trousers. ‘Anyway the smell in this place makes me sick. I don’t know what’s worse – you or the smell.’

‘Now, now, Murgatroyd,’ said Arabella reprovingly, pulling a black petticoat over her flabby shoulders, ‘you know you always feel better after your treatment. Don’t forget the children’s money box on your way out.’

Murgatroyd’s final advice, before he left, was, ‘Try your treatment on the Sanitary Inspector when he calls. It might work wonders.’

After giving this matter a lot of thought and getting nowhere, she decided to call on her parents again. They were rather short on advice nowadays, but she still had faith in their wisdom.

Her mother was still huddled over the fire and she noticed with vague surprise that her father did not draw the sheet over his face. Optimistically, she considered that he could be in a good mood.

‘Mummy, I’m sorry I had no time to bring flowers, but be a dear and tell me the best way to get rid of Sanitary Inspectors.’

Her mother did not move a muscle, or say a word.

‘Tell me what to do,’ wheedled Arabella. ‘Is it chopped worms with sheep’s dropping or rat’s liver with bog myrtles?’

Her mother merely threw a lump of coal on to the fire. Then she softened. ‘See your father,’ she replied.

Arabella leapt over to the bed and almost upset the stained pail lying beside it. She took hold of her father’s hand, which was dangling down loosely. She clasped it to her sagging breast and was chilled by its icy touch, so she hurriedly flung the hand back on the bed saying, ‘Daddy darling, what advice can you give your little girl on how to get rid of Sanitary Inspectors?’

He regarded her with a hard immovable stare then his hand slid down to dangle again. She looked at him thoughtfully and pulled the sheet over his face. ‘Mummy, I think Daddy is dead.’

Her mother took out a pipe from her pocket and lit it from the fire with a long taper. After puffing for a few seconds, she said, ‘Very likely.’

Arabella realised that the discussion was over. ‘Tomorrow I will bring a wreath for Daddy,’ she promised as she quickly headed for the door. ‘I have some lovely dandelions in my garden.’

Back home again, Arabella studied her face in a cracked piece of mirror and decided to give it a wash. She moved a damp smelly cloth over it, which only made the seams of dirt show up more clearly. Then she attempted to run a comb through her tangled mass of hair, but the comb snapped. Thoroughly annoyed, she picked out a fat louse from a loose strand of hair and crushed it with her fingernails. Then she sat down on the bed and brooded. So engrossed was she in her worry she forgot to feed her children, who by this time were whining and squatting in corners to relieve themselves. She couldn’t concentrate on making their food, so she took three of them outside and tied them to posts. The fourth one, under the bed, remained very still. Eventually she decided the best thing to do was to have some of her magical potion ready, though such was her state of mind that she doubted its efficiency in the case of Sanitary Inspectors. Besides, there was no guarantee he suffered from afflictions. Sighing, she went outside. Next to her door stood a large barrel where she kept the potion. She scooped a portion of the thick evil-smelling substance into a delve jar, stirred it up a bit to get the magic going, then returned indoors and laid it in readiness on the table. She was drinking a cup of black sweet tea when the knock came on the door. Smoothing down her greasy dress and taking a deep breath to calm herself, she opened it.

The small man confronting her had a white wizened face under a large bowler hat.

‘Please enter,’ requested Arabella regally. With head held high she turned into the room. The Sanitary Inspector tottered on the doorstep. He had not been feeling well all day. Twenty years of examining fetid drains and infested dwellings had weakened his system. He had another five years to go before he retired, but he doubted he would last that long.

‘Please sit down,’ said Arabella, motioning to an orange box and wondering how she could broach the subject of cures before he could speak about his business. She could see at a glance that this was a sick man, though not necessarily one who would take his clothes off. The Sanitary Inspector opened his mouth to say something but found that he was choking and everything was swimming before him. He had witnessed many an odious spectacle in his time but this fat sagging filthy woman with wild tangled hair and great staring eyes was worse than the nightmares he often had of dismembered bodies in choked drains. Equally terrible was the smell, and he was a connoisseur in smells. He managed to seat his lean trembling shanks on the orange box and found himself at eye level with a delve jar in the centre of a wooden table. Again he tried to speak, but his mouth appeared to be full of poisonous gas.

‘My good man,’ said Arabella, genuinely concerned when she saw his head swaying, ‘I can see you are not well and it so happens I am a woman of great powers.’

She knew she had no time for niceties. Quickly she undressed and stood before him as guileless as a June bride. The small man reeled. This grotesque pallid flesh drooping sickly wherever possible was worse than anything he had ever witnessed.

‘Now just take your clothes off, and you’ll soon feel better,’ said Arabella in her most winsome tone. ‘I have a magical potion here that cures all ailments and eases troubled minds.’ So saying, she turned and gave him a close-up view of her monumental buttocks. She dipped her fingers in the jar and tantalisingly held out a large dollop in front of his nose. It was too much for him. His heart gave a dreadful lurch. He hiccuped loudly, then his head sagged on to his chest.

Arabella was very much taken aback. Nothing like this had ever happened before, though it had been obvious to her when she first saw him that he was an inferior type. She rubbed the ointment on her fingers off on the jar, then dressed. The manner in which he lay, limp and dangling, reminded her of her father. This man must be dead, but, even dead he was a nuisance. She would have to get rid of him quickly if she didn’t want it to get around that her powers were waning. Then she remembered the place where she had buried some of her former children and considered that he would fit into the pram – he was small enough. Yet it was all so much bother and very unpleasant and unpleasantness always wore her out.

She went outside to take a look at the pram. The dogs were whining and pulling on the fence. Feeling ashamed of her neglect, she returned to fetch their supper, when the barrel caught her eye. Inspiration came to her in a flash. The barrel was large – it was handy – and there would be an extra fillip added to the ointment. She felt humbled by the greatness of her power.

Cheerfully she approached the figure slumped like a rag doll against the table. It was easy to drag him outside, he was so fragile. Though he wasn’t quite dead because she heard him whisper, ‘Sweet Jesus, help me.’ This only irritated her. She could have helped him if he had let her. She dragged his unresisting body towards the barrel and with no difficulty toppled him inside to join the healing ointment. With a sigh of satisfaction she replaced the lid. As usual everything had worked out well for her.

GENTLEMEN OF THE WEST

McDonald’s Dug

McDonald’s dog was not the type of animal that people took kindly to, or patted on the head with affection. It was more likely to receive the odd kick, along with the words ‘gerr oot’, which it accepted for the most part with indifference. If the kick was too well aimed it bared its teeth in a chilling manner which prevented further kicks. Large, grey and gaunt it roamed the streets, foraged the dustbins and hung around the local co-operative to the disgust of customers coming and going. The manager, who received continual complaints about it, as if it was his responsibility, would throw pails of water over it to pacify plaintive statements such as, ‘Ye’d better dae somethin’ aboot that dug. It’s a bloody disgrace the way it hings aboot this shop.’ Though he had no heart for this action, as more often than not he missed the dog, which had the sensory perception of a medium and could move like a streak of lightning, causing innocent housewives to be soaked instead. Even so, McDonald’s dog was a valuable asset to its owner. With its height and leanness, plus a sharp, evil face, it might have been a greyhound on the loose, but in fact its character was determined from a lurcher ancestor, an animal talented in the art of poaching. I had an interest in McDonald’s dog due to the following incident.

One particularly dreich evening I was waiting at the bus stop, soaked to the skin. My bones ached from damp clothing. All day I had been sitting in the hut at the building site waiting for the rain to stop in order to get on with the vocation of laying the brick, but it never halted. We played cards, ate soggy pieces and headed with curses for the toilet. On that site it was wherever you happened to find a convenient spot.

So I was thankful when Willie Morrison drew up with his honkytonk motor like something out of Wacky Races.

‘Jump in Mac,’ he said.

I did so with alacrity, hoping the door would not fall on my feet. It was that type of motor.

‘Thanks Wullie.’

We proceeded in silence since Willie had a job to see where he was going. The windscreen wipers did not work too well. I was on the point of falling asleep when suddenly we hit a large object.

‘Watch where yer gaun,’ I said, very much aggrieved that my head had banged against the window. A spray of liquid spurted over our vision. For a sickening minute I thought it was blood, then I realised it was water from the radiator.

‘My God, that’s done it,’ croaked Willie. Panicking, I opened the door regardless of the danger to my feet. I was just in time to see the shadow of an animal limp towards the hedge.

‘Ye’ve hit an animal o’ some kind,’ I said.

‘Whit wis it – a coo?’

‘Don’t be daft. This motor wid have nae chance against a coo. I think it wis a dug.’

‘Och a dug. It’s nae right bein’ on the road.’

He started up the engine and with a great amount of spluttering the car roared off at thirty miles an hour. I felt a bit gloomy at the thought of a dog maybe bleeding to death in the sodden hedgerow, but Willie was only concerned for his car.

‘This motor’s likely jiggered noo.’

I couldn’t be bothered to point out that it was jiggered before. I was only wishing I had taken the bus. We reached our destination without saying much. Hunger had overcome my thoughts on the dog. I hoped my mother had something tasty for the dinner, which would be unlikely.

Some days later I happened to be in McDonald’s company. McDonald was like his dog, very difficult at times. But in the convivial atmosphere of the Paxton Arms we were often thrown together, and under the levelling influence of alcohol we would view each other with friendly eyes. Though you had to take your chances with him. On occasions his eyes would be more baleful than friendly. Then, if your senses were not completely gone, you discreetly moved away. McDonald labelled himself a ploughman. To prove it he lived in a ramshackle cottage close to a farm. Though the word cottage was an exaggeration. It was more like an old bothy. Some folk said he was a squatter, and some folk said he was a tinker, but never to his face. On this occasion I was not too sure about his mood. He appeared sober, but depressed.

‘How’s things?’ I asked, testing him out to see if I should edge nearer to him.

‘Could be better.’

‘How’s that then?’ I asked.

‘It’s that dug o’ mine.’

‘Yer dug?’

‘Aye. Some bastard run him ower.’

‘That’s terrible Paddy.’ My brain was alert to danger.

‘As ye know yersel,’ continued McDonald, unobservant of the shifty look in my eyes, ‘ma dug is no’ ordinary dug. It’s a good hardworking dug. In fact,’ his chest heaved with emotion, ‘ye could say that dug has kept me body and soul when I hudny a penny left.’

I nodded sympathetically. McDonald’s dole money was often augmented by rabbits, hares and pheasants that he sold at half the butcher’s price.

‘An’ d’ye know,’ he stabbed my chest with a grimy finger, ‘I’ve hud tae fork oot ten pounds for a vet. Think o’ that man – ten pounds!’

I didn’t believe him about the ten pounds, but I was relieved the dog wasn’t dead.

‘Where’s the dug noo?’ I asked.

‘The poor beast’s restin’ in the hoose.’

I remembered his house. On one or two occasions I had partaken of his hospitality. A bottle of wine had been the passport. He kept live rabbits in the oven – lucky for them it was in disuse – pigeons in a cage in the bedroom, and a scabby cat always asleep at the end of a lumpy sofa, with the dog at the other end. I don’t know if this menagerie lived in harmony, but they had survived so far. I thought at this stage I had better buy him a drink to take the edge off his bitterness before I shifted my custom. It was obvious his mood would not improve with all this on his mind. McDonald swallowed the beer appreciatively but he was reluctant to change the subject.

‘An’ I’m tellin’ ye, if I get ma haunds on the rat that done it I’ll hing him.’

‘It’s a right rotten thing tae happen.’ To get out of it all I added, ‘I wish I could stay an’ keep ye company, but I huv tae gie Jimmy Wilson a haun’ wi’ his fence, so see ye later.’

Swiftly I headed for the Trap Inn hoping I would see Willie Morrison to break the bad news to him. However, it was a couple of days before I met Willie again. He was waiting at the bus stop motorless, and with the jaundiced look of a man who has come down in the world. He grunted an acknowledgement.

‘Huv ye no’ got yer motor?’ I asked.

‘Naw.’

He shuffled about, then explained. ‘Mind that night we hit that dug?’

I nodded.

‘Well, the motor has been aff the road ever since. And dae ye know whit it’ll cost me tae get it fixed?’

‘Naw,’ I said, although I was not all that much agog.

‘Twenty nicker.’

He stared at me for sympathy. Dutifully I rolled my eyes around.

‘That’s some lolly.’

‘Anyway I’ve pit it in the haunds of ma lawyer.’ His eyes were hard and vengeful.

Before any more was said the bus rumbled up. Justice was forgotten. We kicked, jostled and punched to get on, and I was first. Before Willie managed to put his foot on the platform I turned to him saying, ‘I heard it wis McDonald’s dug ye run ower.’

In his agitation he sagged and was shoved to the back of the queue.

‘That’s enough,’ shouted the hard-faced conductress. The bus drove off leaving Willie stranded.

‘I hear that somebody battered Johnny Morrison last night,’ said my mother conversationally as she dished out the usual indigestible hash that passed for a meal by her standards.

‘Whit’s this then?’ I asked, ignoring the information.

‘Whit dae ye mean “whit’s this”? It’s yer dinner.’

‘I don’t want it.’

‘D’ye know whit I’ve paid for it?’

‘Naw, an’ I don’t want tae.’

‘You really sicken me. Too much money an’ too many Chinese takeaways, that’s your trouble.’

‘Shut up, an’ gies a piece o’ toast.’

‘Oh well, if that’s all ye want then,’ she said, mollified.

She was very good at toast.

Then her opening remark dawned on me. ‘Whit wis that ye said aboot Johnny Morrison?’

She poured out the tea, which flowed from the spout like treacle. ‘Jist as I said. He opened the door aboot eleven at night an’ somebody battered him.’

‘Whit for?’ I asked. I would have seen the connection if it had been Willie.

‘How should I know? He got the polis in but he didny recognise the man. He had a pair o’ tights ower his heid.’

‘Tights,’ I echoed. ‘Do ye no’ mean nylons?’

Stranger and stranger, I thought. I could hardly see Paddy McDonald wearing either tights or nylons, just to give somebody a doing. Anyway, two odd socks were his usual concession to style. And why batter Willie’s brother? Not unless he was out to get the whole family.

I was soon put out of my bewilderment. On Saturday night I saw Paddy McDonald in the Paxton, swaying like a reed in the wind. His expression was one of benignity for all mankind, but like a bloodhound or his lurcher he spied me straightaway.

‘There ye are son. Here whiddy ye want tae drink?’

Straightaway I said, ‘A hauf an’ a hauf-pint.’ I was in a reckless mood and heedless of hazards. It was a Saturday, and I was out to enjoy myself. I was going to get bevvied.

He took a roll of notes from his pocket and waved one of them in the direction of the barman like a flag of victory.

‘You seem to be loaded,’ I said.

‘Aye.’

‘Did somebody kick the bucket and leave you a fortune?’

‘It’s no’ a’ that much,’ he replied modestly. ‘Only twenty pounds.’

‘How dae ye manage tae have that on a Saturday?’ McDonald’s money was usually long gone by that time. He got his dole money on a Friday.

He was lost in a reverie of happy fulfilment. Before he could make any disclosures Johnny Morrison entered. Both his eyes were a horrible shade of yellowish green and there was a bit of sticking plaster above one of them. McDonald regarded him with concern. ‘That’s a terrible face ye have on ye Johnny.’

‘D’ye think I don’t know. Ye don’t have tae tell me!’ replied Johnny with emotion.

‘Have a drink John,’ said McDonald. ‘Wi’ a face like that ye deserve one.’

He waved another pound at the barman.

After doing his duty by Johnny he turned to me and put an arm round my shoulder.

‘I wis really sorry aboot Johnny,’ he whispered.

‘Wis it you that done it then?’

‘Dear God naw, though I know how it happened.’ Dreamily he paused.

‘How?’ Now I was interested and hoped he would not sag to the floor before he could tell me. He swayed a bit then came back to the subject.

‘D’ye know that heid-banger Pally McComb?’

I nodded.

‘Well, I heard it was Wullie Morrison that ran ower ma dug. So I gave Pally a couple o’ rabbits tae gie him a doin’. I wid have done it masel but I didny want involved wi’ the law.’ His voice sank confidentially. ‘As ye know I huvny got a dug licence. Anyway, Pally is that shortsighted that he didny know the difference between Wullie and Johnny, so he banged Johnny.’

‘I see,’ I said, but I didn’t think it was such a great story.

‘How’s the dug then?’

‘I selt it.’

‘Ye selt it?’

‘Aye, it wis gettin’ past it. Matter o’ fact it wis a bloody nuisance wi’ a’ these complaints aboot it. But dae ye know who I selt it tae?’

‘Naw.’

He began to laugh then went into paroxysms of coughing. I was getting impatient. He finally calmed down.

‘It wis Wullie Morrison that bought it.’

I said nothing. I couldn’t make any sense out of it.

‘Ye see,’ McDonald wiped the tears from his eyes, ‘I sent Pally up wi’ a note tae Wullie this afternoon tae say he’d better buy the dug, due tae its poor condition efter bein’ run ower, or else. Well, he must have seen the state o’ his brother’s face, so he sent the money doon right away. Mind ye, I didny think he’d gie me twenty pound. Personally I’d have settled for a fiver.’

‘Wullie could never stick the thought o’ pain,’ I said. I began to laugh as well, and hoped Paddy would keep on his feet long enough to get me another drink.

‘Right enough, Paddy,’ I said, holding firmly on to him, ‘ye’re a great case, an’ I’ll personally see that when ye kick the bucket ye’ll get a big stane above yer grave, me bein’ in the buildin’ trade an’ that.’

McDonald’s Mass

I was taking a slow amble along the river bank. The weather was fine, one of those spring mornings that should gladden anyone’s heart. The birds were singing, the trees were budding and the fishing season had started, but I was feeling lousy. The scar in my temple and the cuts round my mouth were nipping like first-degree burns. My neck felt like a bit of hose pipe and the lump on the back of my head was so tender that even the slightest breeze lifting my hair made me wince. My mother’s remark, ‘You look like Frankenstein’, had not been conducive to social mixing, but since I wanted someone to talk to I decided to look up my old china Paddy McDonald because at times he could be an understanding man if he was not too full of the jungle juice.

I turned with the bend in the river and there on the bank, under the old wooden bridge, was a gathering of his cronies, namely, Billy Brown, Big Mick, Baldy Patterson and Craw Young. They were huddled round a large flat stone that displayed two bottles of Eldorado wine and some cans of beer, but I could not see Paddy.

They did not hear or see me approaching. Billy Brown jumped up as startled as a March hare when I asked, ‘Where’s Paddy?’ at the same time staring hopefully at the wine.

‘Paddy’s died,’ he informed me.

My brain could scarcely adjust itself to this statement.

‘That canny be true.’ Without waiting for the offer I took a swig from the bottle.

‘It’s true right enough,’ replied Billy, smartly grabbing it back. ‘I found him masel up in the Drive as cauld as ice an’ as blue as Ian Paisley.’

The Drive was a derelict building where the boys did their drinking when it was too cold for outdoors.

‘Whit happened to yer face?’ asked Big Mick.

‘That’s a long story.’ I was so stunned by the news that I had forgotten about my face for the first time since I woke up. Billy wiped his mouth with the back of his hand. His eyes were like saucers and his face greyer than grey. He was a close associate of Paddy’s. Not exactly a mate, more like a sparring partner, but they spent a lot of time together except when they were in jail.

‘I didny know whit tae dae, so I got the polis in an’ they sent for an ambulance. They carted him off while I waited ootside.’

‘How dae ye know he wis deid? When Paddy wis out cauld he always looked deid,’ I said.

‘If ye’d seen the colour o’ his face you’d hiv known he wis deid.’ No one disputed this fact.

‘That wis a rerr wee hoose he had,’ said Baldy Patterson wistfully. He was referring to the broken-down bothy where Paddy lived. ‘I think I’ll go up efter an’ see tae his pigeons.’

‘That’s great,’ I said. ‘The man’s hardly cauld an’ ye’re gaun tae move in.’

‘He wis cauld enough when I seen him,’ said Billy. ‘Onyway, somebody has tae feed his pigeons.’

The second bottle was opened and passed around with some beer, and now I was included in the company. Normally I don’t care for wine and beer first thing in the morning, but this day was an exception what with my sore face and Paddy being dead. Now that I was hunkered down on eye level with them they began to study me.

‘Yer face has improved a lot since I last saw ye,’ said Craw Young who always fancied himself as a bit of a wit. ‘Ye’ve got a bit o’ character in it noo.’

‘Better watch I don’t put a bit o’ character in yours,’ I retorted, but I didn’t put any emphasis on my words because they were all away beyond my age group and fragile with years of steady drinking and sleeping out. I thought Paddy had been the toughest despite his burst ulcers and periodical fits if he was off the drink for more than a week, but I was wrong. Mellowed by the wine and the sadness of Paddy’s death, I explained how five fellows from the city had picked a fight with me and stuck broken tumblers in my face. It was really only two fellows but I had my reputation to think of.

‘It’s the bad company ye keep,’ said Billy sagely. ‘We auld chaps know the score.’

‘Is that so,’ I said, ‘an’ jist how many times have you been in jail?’

‘Och, that’s only for disturbin’ the peace and vagrancy. Ye canny count that.’

‘Anyway, Paddy must have been OK this mornin’ if he was in the Drive, otherwise how wid he manage tae get there.’

‘He got lifted last night wi’ the polis as far as I heard, but they must have let him oot early. I didny get in tae the Drive till aboot eleven this mornin’,’ explained Billy.

‘Where were you last night then?’ asked Big Mick with suspicion.

‘I don’t mind much aboot last night,’ said Billy sheepishly. ‘Matter of fact I woke up in Meg Brannigan’s.’

We all jeered. Meg Brannigan was a slattern who drank anything from Vordo to meths. Even Billy was a cut above her.

‘Anyway I jist happened to pass oot on her couch.’

We jeered again.

‘Here,’ said Craw who had been deep in thought. ‘How d’ye know it wisny murder?’

‘It wid be murder bein’ wi’ Meg,’ chortled Big Mick.

‘I mean how d’ye know Paddy wisny murdered?’

‘I never murdered him onyway,’ said Billy vehemently.

‘OK, OK,’ said Baldy, ‘the main thing is whether he wis murdered or no’ who’s gaun tae bury him?’

‘Bury him?’ we echoed.

‘He’s got tae be buried an’ don’t forget that’ll cost money.’

We looked at each other with dismay.

‘He’ll jist have tae go intae a pauper’s grave,’ said Craw with a lack of taste.

‘Terrible tae think o’ poor Paddy in a pauper’s grave,’ said Baldy.

‘It’ll no’ dae him ony harm. He’ll have plenty company.’

‘Maybe he wis insured,’ said Big Mick.

‘Nae chance,’ said Billy. ‘He discussed it wi’ me once. The insurance company wid have nothin’ tae dae wi’ him. He’s whit ye call a bad risk.’

‘Maybe we could get up a collection,’ said Baldy.

‘Who the hell is gaun tae put tae it? Who dae we know that’s got money? I mean real money.’

My face was feeling painful again and I was fed up with all this debate. Paddy had been the only one with any smattering of intelligence about him. Now he was gone.

‘Anither thing,’ said Big Mick. ‘We’ll have tae let the priest know.’

‘First I heard Paddy wis a Catholic,’ said Craw sharply. He turned to Baldy, ‘Did you know that?’

‘Naw, but I always thought there wis somethin’ funny aboot him.’

‘He didny tell me onyway,’ said Craw bitterly, ‘for he knew ma opinion aboot Catholics.’

‘I never knew you had opinions aboot anything,’ said Big Mick. I could see he was becoming angry. Likely he was a Catholic too with a name like Mick.

‘Anyway,’ Billy Brown butted in, ‘you don’t even know whit you are. You telt me ye wir an orphan.’

‘I might’ve been an orphan but I wisny a Catholic.’

‘Who cares?’ I said.

We all glared at each other for some seconds. Then to prove how displeased he was with the subject Big Mick finished off the remainder of the wine in one swallow. We stared gloomily at the empty bottle.

‘I’m off,’ said Mick with the air of a man who is going to get things done. He threw the bottle into the river and marched off with as much determination as his long shaky legs would allow him.

I said, ‘Me too.’ Groggily I arose, wishing I had gone to work. It couldn’t have been any worse.

After the evening meal of sausages and mash, one of my mother’s favourite dishes, I sat staring glassily at the television. I didn’t particularly wish to venture into the Paxton Arms to meet types like Willie Morrison. He would be overjoyed at the brilliance of my savage face and even more so at the news of Paddy’s departure. After all, he had been so terrified of Paddy he was forced to buy his dog, and Willie hated that dog, though he was too frightened to get rid of it. And that dog, for all its mean look, had a loving nature. It trailed on Willie’s heels like a shadow. Willie would dodge up closes to avoid it, but to no avail. It could always seek him out panting and slavering with joy. With Paddy gone the dog was definitely a goner too. My mother sat down to view the telly twitching about and straightening cushions. I suspected my company was a bit of a strain for her. I said, ‘Did ye know that Paddy McDonald is deid?’

‘Is he?’ she replied in a flat voice. We both stared at the box. Finally she said, ‘He’ll no’ be much loss anyway.’

‘I suppose not.’ I kept my voice neutral.

‘He wis nothin’ but a tinker anyway,’ she added.

‘There wis nae proof he wis a tinker.’

‘He wis worse. He wis just a drunken auld sod that neither worked nor wanted.’

I let the remark go. I could not expect her to have any understanding of Paddy.

‘By the way,’ I said, ‘I heard he wis a Catholic. If he just died this mornin’ when wid they haud his mass?’

‘Usually the same night, I think.’

‘Whit time aboot?’

‘Maybe seven. I mind that’s when they held mass for Mrs Murphy.’ Then looking aghast she added, ‘Don’t tell me ye’re gaun tae the chapel for that auld rotter.’

‘Don’t be daft,’ I said, but inwardly I thought I should. It would be the decent thing to do. I was feeling a bit emotional about it all, and stood up quickly before she noticed my eyes were wet.

‘I’m away oot,’ I said before any more remarks could be made.

I headed for the chapel with a lot of indecision. It’s right next door to the boozer which is handy for the Catholic voter. I noticed there was more business going for the chapel though. You would have thought there was free beer by the manner in which everyone rushed up the stairs. I hung about until the rush was over and looked up and down the street furtively. Which was it to be, the boozer or the chapel. Then I thought, what the hell, I should pay my respects to Paddy. I took the plunge and scurried up the stairs. I didn’t know what I expected to see behind these dreaded doors, but apart from a couple of statues and something that looked like a fancy washhand basin, there was nothing much to put me off.

I sneaked in through another door to be confronted with all the solemnity of the papal worship. My face was red as I squeezed into a bench at the back because all the seats were jam-packed. But not a soul bothered or even gave me a glance, so engrossed were they in the sermon. The priest’s voice was a meaningless drone to me, and I wondered if the mass for Paddy had begun. After a time I felt relaxed enough to look around at the decor. I considered it quite tasteful and if anything, except for the odd statue here and there, quite plain. I liked that. It was peaceful and uplifting. Maybe Paddy’s death had a meaning for me. Maybe it was to join this mob and get a bit of religion. Definitely food for thought. Though it would be fine if I could hear what the priest was saying, but whatever it was it would be appropriate and Paddy would be pleased if he could hear. Probably he could. In this place anything was possible. Then it struck me I couldn’t see Paddy’s coffin. Perhaps it was too early for this. I wished I knew more about these matters. To see if it was lying handy I stood up. An old woman sitting next to me whispered as loud as a shout, ‘Sit doon son. It’s no’ time for staunin’.’

I sat down quickly. No sooner had I sat when everyone stood up. For the next half-hour we were up and down like yo-yos. Though you didn’t sit all the time you were down. Sometimes you had to kneel on the long stool on the floor. I was beginning to get the hang of it but it was very sore on the knees. Still there was no sign of Paddy’s coffin, nor had I heard a mention of his name. At one of the sitting parts I whispered to the old woman next to me, ‘Could ye tell me missus if the priest is saying mass for Paddy McDonald?’

I don’t know if the message got through but her reply made no sense.

‘Look,’ she said balefully, ‘I don’t know anything aboot Paddy McDonald, but whatever they tell you I’ve lived a decent life for the past ten years and atoned for everything. I’m never away from this bloody place atoning – so don’t start.’

Her voice finished on a hysterical note. All eyes that had been transfixed forwards were now transfixed backwards on me. The priest, as distant as a postage-stamp picture, had stopped swinging the smoky stuff. I was so burnt up with embarrassment I felt my wounds were opening up to drip blood. I wiped my face on an ancient paper hanky but sweat only dampened it. Then the pressure was released. The eyes turned away and the priest carried on swinging the smoky stuff. I had scarcely got over all this when, out of the blue, everyone got up from their seats and began to walk down the aisle in a single file, even the old woman. I couldn’t stand any more so I stood up as though I was going to join the queue but instead turned quickly to the right, out of the door, passing the fancy washhand basin and into the marvellous fresh air. It was the only sensible thing I had done all day.

* * *

The first person I bumped into, or rather he bumped into me, was Paddy McDonald. I wasn’t all that surprised. The absence of his coffin or any mention of his name had cast doubts anyway. I didn’t want to know him now. He was in one of his complicated, mindless moods. In other words, completely stoned. He clung to me as if I was a long-lost lamp-post. If he had been sober there were a million questions I could have asked him, but as it was I merely said, ‘Hi Paddy.’

Stoned though he was, he was bursting with information. ‘D’ye know whit I’m gaun tae tell ye?’

‘Whit?’ I said.

‘Because o’ that stupid sod Billy Broon I wis carted off tae hospital this mornin’. They widny let me oot. Telt me ma liver was a’ tae hell. It took me a’ day tae get ma haunds on ma clathes.’ He paused to regain the drift of his conversation, still gripping me tightly. ‘Noo they tell me that Billy an’ the team are in ma hoose lettin’ a’ the pigeons away an’ God knows whit else. Wait till I get ma haunds on the bastards.’

I tried to break from his vice-like grip, saying, ‘Ye’d better hurry hame then before they set yer hoose on fire.’

In his agitation he released me. Facing the Catholic church, he uttered every blasphemy he knew. It seemed to me that Catholics are a very extreme lot. If they are not one way they are the other. Of course that is only my opinion. In the middle of it all I walked away. Though I hoped he had the energy to batter Billy Brown to a pulp for the bother he had caused me. And all this had to happen when I had a sore face.

Grievous Bodily Harm

‘Any old rags! Toys for rags! Any old rags!’

The voice of Duds Smith, magnified through an old tin trumpet, roared up our street, penetrating the thickest eardrum.

‘I wid jist as soon burn ma rags than gie them tae that auld cheat,’ said my mother in her usual arrogant style.

‘I thought ye usually wore them,’ I muttered.

‘Whit’s that?’

‘Nothing.’ I then added the uppermost thought in my mind, ‘How’s about a pound till Friday?’

‘Don’t be daft. For a’ the money you gie me I couldny afford nothing.’

She went on to explain at great length that I must be unaware of the fact the cost of living had risen in the past five years and surely I must realise the fiver I gave her every week would hardly keep a dog going. Fixedly I stared out of the window. I knew she would eventually wear herself out then begin to feel guilty at my lack of defence. At the least I might get fifty pence from her which was the entrance fee for the Paxton Arms. Her tirade petered out and she sat down breathing heavily while Duds’s voice penetrated the pregnant silence. His motor was now opposite our window. Kids were running out with bundles large and small leaving a trail of scruffy articles behind them while Duds was handing out balloons and Hong Kong whistles in a benevolent style and deftly slapping to the side any of them who were returning burst balloons and soundless whistles.

‘Mean auld swine,’ said my mother as she joined me to survey the scene. I knew she was playing for time.

‘Here, I tell ye whit,’ she said suddenly excited, ‘gie Duds that auld telly lyin’ in the bedroom an’ ye can take a pound aff the money ye get.’

‘Don’t make me laugh!’ I allowed the flicker of a smile to crease my face which was just beginning to heal from the broken tumbler episode. ‘Ye’d have tae pay him tae take that telly away. It must be the original one Baird invented.’

‘It could be fixed easy. Ye can still get a picture.’

‘I’ll tell ye whit,’ I said, not wishing to waste time on the merits of the television, ‘I’ll take the telly doon tae him if you gie me a pound for tryin’, whether he takes it or no’.’

‘OK,’ she said.

Duds was not thrilled when I laid it down on the pavement. My arms were almost wrenched from their sockets with the weight.

‘Look Mac, I’ve more televisions in ma back yard than auld lawnmowers.’

‘Maybe,’ I gasped for breath. ‘But this one still works.’

He stared at it in disbelief.

I explained, ‘Ye see, we’ve got a new telly, so ma mother wants rid o’ this one, but if ye don’t want it I’ll take it doon tae auld Mrs McMurtry. She said she would gie us a fiver for it, that is if ye could oblige me wi’ a lift roon tae her hoose.’

Duds was convinced. ‘I’ll gie ye two pounds for it.’

‘It’s a deal,’ I said.

I told my mother, ‘Duds only gave me a pound.’

‘Is that all?’

‘Ye were lucky even tae get that.’

‘Have I tae get the pound then?’ she asked hopefully.

I became indignant at the way she was trying to get out of her deal. ‘C’mon, ye said ye’d gie me a pound if I got rid o’ it or no’, so I keep the pound an’ you’ve saved a pound.’

‘I gie up,’ was her final comment.

* * *