Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Pocket Essentials

- Kategorie: Fantasy und Science-Fiction

- Sprache: Englisch

For nearly forty years, from his earliest work in underground Arts Lab projects to his latest work as author of League of Extraordinary Gentlemen and Lost Girls, Moore has pushed the boundaries like few others, ranging from farce and high comedy to the dark, grim work that epitomised the comics revolution of the late eighties. This book examines the recurring themes and how Moore's work has evolved over the years from his early comic work in Captain Britain and 2000 AD, through milestone series like V for Vendetta, Marvelman, Swamp Thing and Watchmen, to his current genre-stretching work. On the way Moore has written definitive stories of America's greatest superheroes Batman and Superman, penned some of the most widely read graphic novels of all time, and helped turn comics into an indispensible art form. In this Pocket Essential you'll meet Moore the pop icon (everyone from the Simpsons to Transvision Vamp have hung out with Halo Jones), Moore the performance artist and magician, Moore the novelist, and above all Moore the writer who helped change the face of comics forever. As well as an introductory essay, this book is a comprehensive survey of Alan Moore's career. It also contains a complete list of his works, including projects that never saw the light of day.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 243

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2011

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

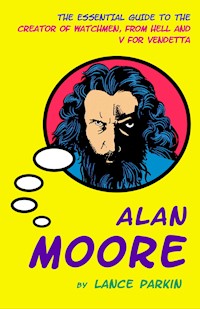

Alan Moore

Lance Parkin

www.pocketessentials.com

Thanks to Allan Bednar, Simon Bucher-Jones, Graeme Burk, Paul Castle, Mark Clapham, Steve Holland, Rich Johnston, Mark Jones, Greg McElhatton, Jim Smith and Paul Duncan.

CONTENTS

Title Page

Acknowledgments

1. Alan Moore Knows the Score

2. The British Years

3. America

4. The Wilderness Years

5. The Return

6. Beyond Fifty

7. Bibliography

Copyright

ALAN MOORE KNOWS THE SCORE

Alan Moore is the best writer of comic books there has ever been.

That’s a bold statement and it’s not one that’s meant to demean the efforts of many others who have worked in the medium. There have been more prolific and more commercially successful writers, ones who have created dozens of characters that are now household names. But there have been no writers who have worked so well in so many different genres, whose work has moved the form into new literary and artistic areas, garnering so much critical praise, or whose work is so eagerly anticipated.

Moore’s closest rival by these criteria is Grant Morrison, author of The Invisibles and All-StarSuperman. Morrison has written some wonderful series like We3 and Doom Patrol and is consistently versatile and inventive. But while he has found a way to retain his distinctive voice in ultra-mainstream books like New X-Men and Final Crisis, and while all his work is often personal and compelling, he has yet to lay down landmark graphic novels like Moore.

There have been other works with a claim to be the best comic book: Frank Miller’s Dark Knight Returns, Katsuhiro Otomo’s Akira, Neil Gaiman’s The Sandman, Jodorowsky and Moebius’ The Incal, Bryan Talbot’s The Adventures of LutherArkwright, or Art Spiegelman’s Maus, among others. But their writers have tended not to be prolific, or their other work has failed to demonstrate the sheer variety and depth of Moore’s.

So, let’s do the list: among many other things, major and minor, Alan Moore has written The Ballad of Halo Jones, Watchmen, Marvelman, (known in the United States as Miracleman), VforVendetta, Swamp Thing, ‘Whatever Happened to the Man of Tomorrow?’, The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen, The Killing Joke, Lost Girls and From Hell. Ten stories, ranging from long runs in weekly or monthly comics, through limited series to one-off specials. All of the above have a good claim for a place on anyone’s ‘best of’ list, but, taken together, it’s simply an unrivalled body of work.

Moore is also an important figure in the recent history of comics. He was the first comics writer living in Britain to do prominent work in America. Since the mid-eighties, following in Moore’s footsteps, a whole wave of writers and artists has crossed the Atlantic to work on some of the real icons of American popular culture. Nowadays, if you pick up a superhero comic from the States, there’s a good chance it’s written or drawn by someone from the UK. The other thing that distinguished Moore in the early eighties was that he was famous solely for his writing, rather than as a writer/artist (just as many acclaimed cinema directors are actually writer/directors). Moore manages to be an auteur in the medium without drawing – an achievement in itself.

Alan Moore was born in Northampton in 1953, to working-class parents (his father, Ernest, worked in a brewery, his mother, Sylvia, at a printers). He still lives in Northampton and the town has often featured in his fiction. He avidly read British comics like The Topper and The Beezer, and when he was seven he discovered his first American comics (Flash, Detective Comics and other DC titles) on a market stall. In the sixties, American comics were widely distributed in Britain as importers bought up unsold stock and returns cheaply; Moore soon discovered Fantastic Four issue 3 and became a regular Marvel reader of whatever titles were available in the UK, the distribution system being imperfect. Some weeks that would mean Atlas monster books. On bad weeks it would be Caspar the Friendly Ghost.It was an eclectic mix and he clearly has a lot of affection for the comics of his childhood because they have formed the foundation for a lot of his work.

Four types of comics in particular have been clear influences. When Moore was very young, horror comics were a focus for parental outrage on both sides of the Atlantic. In particular, those published by EC were full of gruesome violence – beheadings, disfigurements and the like. In Britain the Eagle was launched as a moral counterpoint to them. In America the Comics Code Authority was set up to regulate the industry. Superheroes like Superman, Batman and Captain Marvel were more wholesome, and these have been the staple of the industry since the late thirties. While Britain has never embraced home-grown superheroes, preferring more straightforward science fiction characters like Dan Dare or Judge Dredd, there were a few British superheroes, like Marvelman, and these tended to mix science fiction and fantasy motifs with the more straightforward heroics. At the age of 15, Moore was still reading mainstream comics from a wide variety of companies like Charlton, which published a slightly more politically sophisticated type of superhero, and ACG, enjoying them all. At the same time, he was discovering underground comix and magazines that fell between those and the mainstream: Wally Wood’s Witzend and Bill Spicer’s Graphic Story Magazine, which reprinted Will Eisner’s TheSpirit and which Moore considers the best comics fanzine ever. These titles were influential at a time – by now the late sixties – when Moore was discovering the early days of British comics fandom and was exposed to EC titles, MAD Comics reprints and the work of William Burroughs and the Beat writers in America and home-grown counter-culture magazines like Oz.

Comics have always represented a subculture – one with its own language and role models, and a sense of its own history and myth. Names like Will Eisner, Harvey Kurtzman and Jack Kirby, meaningless to outsiders, are held in awe. The letters pages and fanzines have codified an unfolding history of comics and, as some titles have been in continuous publication for 60 years or more, it is possible to trace developments and changing tastes over generations. Naturally, all sorts of narrative conventions and traditions have evolved. The comics industry is insular and its main subject matter is comics itself – endless reiterations of characters’ narrative history and a self-sustaining mythology of a ‘golden age’ in the past. Adult readers are encouraged to view comics as limited edition pieces of art. Price guides often start with ten-page descriptions of exactly what sort of plastic bag comics should be kept in, which cardboard boxes and even which way up comics should be stored. Moore has always had an uneasy relationship with this. In one of his first published stories, ‘Profits of Doom’, a short one-off strip in the Eagle, a comic collector rips off someone selling him a rare fifties’ horror comic, but gets his come-uppance when the comic comes to life and kills him. It’s a simple tale and one that doesn’t need an in-depth knowledge of comics history, but Moore has that knowledge and knows many of his readers will.

A lot of Moore’s work is concerned with the history of comics – subverting it, redefining it, challenging it, or often just celebrating it. It’s the medium he’s interested in: the form, how to tell stories with it and the subject matter. He recognises the iconic power of the stories – archetypal battles between good and evil – but clearly feels they can be put to better use than they have been in the past. His recent work has moved away from superheroes, but Moore has broadened his thesis to encompass all types of popular narrative, from adventure fiction (The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen, Tom Strong), children’s stories (Lost Girls) to tabloid journalism (From Hell), to create what has been described as ‘a grand unified field theory of fiction’.

Throughout his career, Moore has returned to the most iconic superhero of all – Superman. Superman stories have provided him with fertile ground. Superman has been the backbone character of the industry for more than 60 years and one of the great icons of the twentieth century, recognised around the world. Most people can describe the basic set-up: the man who’s strong, who can fly, who wears his pants on the outside and who works in a big city at a newspaper with the woman he loves. It’s a myth rooted in the real world, but one that’s a childish fantasy.

Time and again, Alan Moore has told Superman stories. In the early eighties, he wrote Marvelman, which was about a Superman in the real world, where the normal rules of comics didn’t apply. In these stories things changed and people got injured. The approach Moore adopted on Marvelman would help start a revolution. It would make Superman into an anachronism and by 1986 would lead to a more realistic revamp of Superman himself. Fifty years of history were streamlined, or, if it was felt to be too childish, just erased. Ironically, it was Moore who told the last old-style Superman story, ‘Whatever Happened to the Man of Tomorrow?’, and it had more power and poignancy than just about any Superman story told before or since. There was a real sense of regret as Moore closed one chapter of the character’s life, with the supporting cast of playful childhood companions, superdogs and magical imps being put to the sword. Ten years later, with the new Superman sensibly married to Lois, with Lex Luthor a corporate player rather than a mad scientist, Moore’s work on Superman rip-off Supreme was almost an act of atonement, as he lovingly recreated every last absurdity of the old-style Superman, making them work for a modern audience. Then, as the millennium approached, Moore created Tom Strong, a superman character that takes the concept back to basics by invoking the pulp and legendary archetypes that inspired Superman. Moore tells these stories with a simple, primal appeal.

One of Moore’s favourite story devices has been to take superheroes out of their storybook world and place them in a world more like our own. Moore wasn’t the first person to try to treat superheroes realistically, or to imagine them operating in the real world. From the late sixties on, a number of titles reflected social changes and fears. The X-Men portrayed a group of people feared by society at large, and the arguments between the peaceable Professor X and the militant Magneto echoed those between Martin Luther King and Malcolm X. A celebrated run of GreenLantern/GreenArrow by Denny O’Neil and artist Neal Adams had dealt with issues of racism, poverty and drug abuse. Poor black city dwellers berated Green Lantern for worrying more about alien invasions than ‘real problems’. Green Arrow’s kid partner, Speedy, became a heroin addict.

The seventies saw a new generation of socially aware superheroes like Hawk and Dove – one a soldier, the other a pacifist – and superheroes who could never be allowed to forget their ethnic origin, like Black Lightning and Black Panther. Some of these were clever, well-told tales. Others were simply embarrassing. The worst was almost certainly Lois Lane 106, in which (thanks to Kryptonian technology) the intrepid reporter became a black woman for a day to research a story. But all of them, whether good or bad, reflected the fact that publishers were beginning to recognise that comics were being read by an older, more sophisticated audience than had traditionally been the case.

Outside comics, other authors addressed the problems inherent in superheroes. Larry Niven’s widely reprinted 1971 essay, ‘Man of Steel, Woman of Kleenex’, speculated about Superman’s sex life and the practicalities of being invulnerable and super-strong. One big influence on Moore seems to have been the satirical novel Super-Folks by Robert Mayer (1977), about a Superman-like hero who has retired, grown fat and become increasingly impotent in any number of ways. Moore’s work echoes the book in a number of places: the idea of Superman giving it all up to live a normal life has been a recurring theme; the police going on strike because the superheroes are stealing their jobs is a key plot point in Watchmen; also, Super-Folks and ‘Whatever Happened to the Man of Tomorrow?’ have the same ending – a formerly mischievous but now truly evil pixie character is behind the events of both. Moore has said that Super-Folkswas ‘a big influence on Marvelman. By the time I did the last Superman stories I’d forgotten the Mayer book, although I may have had it subconsciously in my mind, but it was certainly influential on Marvelman and the idea of placing superheroes in hard times and in a browbeaten real world.’

But Moore’s approach went beyond espousing liberal causes or pointing out the logical shortcomings of superhero comics. At the end of the eighties, Moore and a precious few others seemed about to initiate a shift that would see the comic book – or sequential art, or whatever you want to call it – become an accepted medium, as it is in France, Italy and Japan. It would become as easy and as socially acceptable to buy a comic as a book or a CD. Moore was the most prominent figurehead of the revolution in comics that hit the industry in the late eighties. For a few years, comics boomed. Sales and back-issue prices rocketed, publishers found themselves signing six-figure royalty cheques, and the promised land of mainstream acceptability seemed only a few steps away. Comic books were rebranded as graphic novels, while their writers were invited onto literary review programmes and treated like any other novelist. Long articles in colour supplements discussed the iconic stature of Superman and the significance of Batman. Avid fans, new readers and the literary establishment alike lapped up comics.

Alan Moore was at the centre of this revolution. Indeed, in James Park’s 1991 book, CulturalIcons, Moore’s entry is longer than Madonna’s or Robert de Niro’s, and only a couple of lines shorter than the entry for The Beatles. Along with Dark Knight Returns, Moore’s Watchmen was the book that everyone who was anyone was reading. It invaded pop culture in a way that seems barely plausible now – Bomb the Bass adopted the Watchmen badge (a smiley face with a splash of blood) as its own, and it became one of the great iconic images of 1987. Terry Gilliam was going to direct the film. It was possible to buy a leather-bound slipcase edition of the story. The summer of 1989 saw Tim Burton’s Batman break box-office records. While most contemporary publicity suggested that Burton’s film was an adaptation of Dark KnightReturns, it actually bears little resemblance to Miller’s story – the retro-forties look and the Batman/Joker relationship came from Moore’s The Killing Joke. That year, the chorus of Can U Dig It by Pop Will Eat Itself proclaimed ‘Alan Moore knows the score’.

The obvious question to ask, then, is: ‘Where did it all go wrong?’

Nearly twenty years on, most large bookshops still have a small graphic novel section, but it seems like an awfully long time since Penguin Books published graphic novels. After a few years, comics retreated to their comic shop ghettos. Despite all the promises of cataclysmic change, and the fact that many non-superhero movies, big and small (such as 300, Whiteout, Sin City, Art School Confidential and Road to Perdition) were originally comics, the meat and drink of the comic book industry remains stories about musclemen and pneumatic women punching each other. That the movie industry can get the masses to watch superheroes like Batman, Spider-Man, The X-Men and Iron Man, and that television shows like BuffytheVampire Slayer, Smallville and Heroes get huge audiences and critical acclaim for mining superhero comics only makes the original medium’s failure to capture the imagination more depressing.

As the nineties began, the economy turned from boom to bust and the value of people’s comics collections collapsed like the price of houses, vintage cars and Impressionist paintings. There was also increased competition for young men’s money, with ever more computer games, sell-through videos and magazines being targeted at them. But, even so, comics are still relatively cheap items and should have weathered the storm better than they did.

Quite simply, the boom ended because there weren’t enough good comics out there to appeal to people. If you want to watch great cinema, you can watch a classic film a week and you’ll die before you’ve seen them all. Likewise with classic novels, music, even television programmes – you’re spoiled for choice. In a recent guide to writing comics in Wizard magazine, industry stalwart Mark Waid stated that the only comics you actually need to read are Watchmen, Maus and Dark Knight Returns, all of which were written in the eighties. Even with an expanded list, if you want to read all the great comics, you really don’t need to take more than a week off work. The people who came to the medium because of Watchmen quickly left – there was little more to see. DC’s Vertigo imprint remains, but it’s often been little more than a pale shadow of Moore’s old work. SwampThing continued without him, various members of the supporting cast appeared in other series. John Constantine, created by Moore for Swamp Thing, has appeared for 20 years in his own contemporary horror title, Hellblazer (and a movie version, Constantine). The Sandman, one of the few successful comic books to appeal to non-comics fans, was often, in its early days, little more than a replay of a few of Moore’s Swamp Thing riffs. Those are among the best. Far too many of Moore’s imitators took realism to mean an adolescent preoccupation with bodily fluids and swear words. None of Moore’s intricate, thoughtful use of the medium, let alone his sense of humour and playfulness, survives. And as for superheroes… when the bubble burst, comics companies played it safe. They couldn’t afford to support loss-making products, so they desperately tried to retain a collectors’ market by issuing superficialities like variant covers and gimmicky stories.

Alan Moore was, again, a crucial figure. A prolific, high-profile writer, Moore severed his ties with DC in the late eighties, set up his own company, Mad Love, and started doing more avant-garde work for independent publishers. It was an exciting prospect – the equivalent of Spielberg breaking away from the studio system and setting up DreamWorks SKG. But the recession turned a sure thing into disaster – even the major companies hit serious trouble, and Marvel, the biggest publisher in the industry, filed for bankruptcy in 1997. Mad Love collapsed. Moore’s projects became dogged with production and distribution problems.

From Hell is the best case in point. It is an extraordinary piece of work, easily in the Watchmen/Dark Knight Returns/Maus league. Taking on the Jack the Ripper legend, Moore has created a postmodernist masterpiece – a comprehensively-researched analysis of the case, which doesn’t shy away from a visceral depiction of violent acts, but also imbues them with symbolic and metaphorical importance. Moore and artist Eddie Campbell have created a world where contemporary engraving and portraits come to scratchy life. At first, it couldn’t be further from the glossy, colourful worlds of Watchmen or The Killing Joke, but the style becomes compelling, integral to the story being told. This isn’t simply a prose novel with pictures, or the storyboards for a film – it has to be a comic strip. At heart, it’s a great story, an utterly compelling solution to the murders, which then deconstructs itself. It moves the comic strip form forward.

But, almost from the start, From Hell was plagued with difficulties. Moore started work on the series in 1988, but it would be ten years before the last instalment was published. Originally intended to appear in Steve Bissette’s horror anthology, Taboo, and then collected into comic book format, the series was hit twice, first by the collapse of Taboo and then the bankruptcy of Tundra, who had taken on publication of the story. Even switching publishers, From Hell appeared irregularly – no more than two issues a year, seemingly released at random intervals. Distribution was patchy. It was a resolutely uncommercial prospect, with each issue being black and white and having a high cover price, and comic retailers were in the middle of a distribution crisis. Customs and police seized the consignments in a number of countries including Australia, South Africa and England. Collecting the entire series was beyond the abilities of even some of Moore’s most dedicated fans, with the result that all critical or sales momentum was lost.

Now, ironically, it is one of Moore’s best-known works, as it was made into a film starring Johnny Depp and Heather Graham. FromHell is utterly unfilmable – it’s a vast work, full of digressions and subplots. As with other complex works such as The English Patient, ambiguities and multilayered storytelling were stripped away by the filmmakers in favour of a straightforward, rather mediocre, genre story. But the momentum from the film meant that the original comics were collected into a trade paperback and From Hell finally took its place as a best-seller and landmark work.

In the mid-nineties, Moore returned to superhero comics. No doubt he could have made a very comfortable living ploughing the same furrows he had in the eighties, or won awards for more avant-garde work, but he had no interest in that. Instead, he horrified some of his fans by writing colourful superhero books. Moore had created a revolution, then disowned it. He renounced the crass commercialism of superheroes, then returned to write for Image comics, surely the most crassly commercial publisher he could have hoped to find. After a period during which he concentrated on other long-held interests like performance art and magic shows, which now drew greater attention because of his raised profile, he returned to create a range of colourful, archetypal comics characters.

This coincided with a flowering of innovation and increased commercial success, with ‘fanboy’ culture becoming mainstream. Alan Moore’s influence on movies like The Incredibles and the TV show Lost has been openly acknowledged by their creators. Moore has appeared as himself on The Simpsons. There are now half a dozen movies based on his work, but while many comics creators eye career moves to film and television, Moore uses the reverence and selling power of his name to produce challenging, one suspects deliberately unfilmable work. After more than a quarter of a century in the toils, Alan Moore remains a central creative force in comics and their best hope.

THE BRITISH YEARS

SECRET ORIGINS

Alan Moore started, as most British comics writers have, by graduating from drawing for local magazines to writing one-off strips for a variety of publications, gradually building a reputation and being allowed to tell the sort of stories he wanted to, rather than ones dictated by a limited page count and the needs of an editor. As with every freelancer, though, at first Moore had to identify magazines that would pay money to comic strip writers, then work to their strictures.

Moore began contributing to xeroxed Northampton Arts Lab magazines, Embryo and Rovel. His work at the time was clearly influenced by magazines like Oz and included poems, comic strips, art and prose. A picture used as an advertisement for the SF shop Dark They Were and Golden Eyed in 1969 in the pages of the British underground comic Cyclops marked his first appearance in anything approaching a professional magazine.

Moore was expelled from school at seventeen for dealing acid, telling the BBC in 2008 that: ‘The problem with being an LSD dealer, if you’re sampling your own product, is your view of reality will probably become horribly distorted and you may believe you have supernatural powers and you are completely immune to any form of retaliation and prosecution, which is not the case.’ Following this, he had a succession of menial jobs, such as working in a sheep-skinning yard and cleaning toilets at the Grand Hotel in Northampton. During the seventies, Moore came close to a breakthrough a couple of times, as a number of publishers and editors toyed with new superhero or SF comics, but these all fell through – until the success of the movies Star Wars and Superman, publishers doubted there would be a large audience for science fiction, fantasy or superheroes. An early sample sent by Moore to DC Thomson was set in a fascist future and involved a costumed character known as The Doll, concepts which later resurfaced in V for Vendetta, but it was unsuitable for Thomson’s young audience. Undaunted, Moore – then working in an office and with a baby on the way – continued to explore opportunities to create illustrations and comic strips.

‘Anon E. Mouse’ was produced for the local underground paper Anon, followed by ‘St. Pancras Panda’, which Moore describes as ‘Paddington Bear in Hell’, for Back Street Bugle, an Oxford-based alternative magazine, which was Moore’s first experience of meeting deadlines and creating punchlines for the fortnightly episodes. For Dark Star, a fanzine for west coast music, Moore worked with Steve Moore (no relation), whom he had known since the age of 14, on ‘Three Eyes McGurk and His Death Planet Commandos’, which featured the first appearance (and subsequent death) of Axel Pressbutton. The strip, pencilled by Moore, was picked up by Gilbert Shelton for the British New Talent issue of the American underground Rip-Off Comix.

His first professional sale – as none of his work to date had been paid – were illustrations to the music magazine NME. Realising that illustrations alone would not support him, Moore submitted a strip to Sounds, which began to appear (as by Curt Vile) in early 1979: ‘Roscoe Moscow’ was a satirical strip encompassing music, nuclear war, fascism and aliens, which Moore followed up with ‘The Stars My Degradation’, with Steve Moore, which combined Star Wars imagery with the playful subversion of underground comix. His second regular paying gig – ten pounds a week – was ‘Maxwell the Magic Cat’, which he wrote and drew for his local newspaper, the Northants Post. The strip started in 1979, with Moore continuing to supply a strip each and every week until 1986 – well beyond the point he was making good money from his American work. Maxwell seemed conceived as an antidote to Garfield and, instead of ending with a twee joke or trite homily, tended to dwell on the everyday, such as strikes and riots, or, more often, that cats ate mice and had fleas. While some of the strips are funny and imaginative, it would be a stretch to say that ‘Maxwell’ was great, but it remains easily Moore’s longest-running continuing series and the strips are interesting snapshots of how his mind works.

1980 represented a turning point, as Moore started working for the weekly 2000AD, published by IPC. The comic had only been around since 1977, but was selling well and had become an important focus for the British comics scene – and one character in particular, Judge Dredd, had quickly become very popular. The production values on 2000AD were primitive by current standards. As with every other British comic of the time, it was printed on newsprint, with expensive colour pages being reserved for the centre spread and the cover (so limited was the use of colour that half the artists working on early ‘Judge Dredd’ strips thought he was black, the other half thought he was white!). Each issue had five or six strips, around four to eight pages each. Only ‘Judge Dredd’ appeared every week without fail, and there was a balance between other established, long-running series like ‘The A.B.C. Warriors’ and ‘Strontium Dog’ and one-off stories, often only two or three pages, with a simple twist or shock ending – although the banners they usually appeared under, Tharg’s Future Shocks and Time Twisters, blunted the sting somewhat. One seemingly minor innovation was having huge consequences – the artist and writer were credited for their work, with the result that readers understood comics were something that people wrote, not things that magically appeared. If you were interested, you could follow the work of your favourite writers and artists as easily as you could the characters and this led to 2000AD’s readers becoming ever more literate in the medium. In the book Writers On Comics Scriptwriting, acclaimed writers Garth Ennis and Warren Ellis both trace their interest in writing comics to one article in the 1981 2000ADAnnual (which, as is traditional with British annuals trying to prolong their shelf life, actually came out in the autumn of the year before the cover date). The Annual