Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Cinnamon Press

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

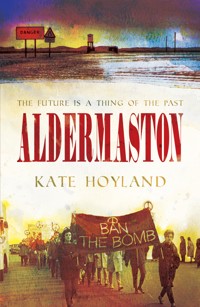

2121: Wading through a drowned fenland, Jean is searching for a lost village and a hillside church that appears only in dim memories of the world before it was engulfed by rising sea levels, deserts and floods. She is looking for a time capsule buried over 160 years ago, a symbol of hope for a different future. 1958: Coming of age in a drab and exhausted post-War London, Ida finds herself questioning the assumptions of her mother and her Uncle Roy. Wanting more from life, she is drawn into circles of political activism, jazz clubs, and life lived on the margins of conformist society – places where there are as many questions as there are possible answers. Separated by decades and a planet turned upside down by climate shifts, the lives of these two women begin to draw together. As Jean closes in on the location of the time capsule and Ida prepares to take part in the first Ban the Bomb march to the nuclear weapons research centre at Aldermaston, their fates dramatically collide.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 457

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Contents

Dedication

Jean

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

Ida, 1957

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

Jean, 2121

1

2

3

4

ALDERMASTON

KATE HOYLAND

Published by Cinnamon Press, Office 49019, PO Box 15113, Birmingham, B2 2NJ

www.cinnamonpress.com

The right of Kate Hoyland to be identified as author of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patent Act, 1988. © 2021 Kate Hoyland.

Print Edition ISBN 978-1-78864-121-0

Ebook ISBN 978-1-78864-117-3

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data. A CIP record for this book can be obtained from the British Library.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior written permission of the publishers. This book may not be lent, hired out, resold or otherwise disposed of by way of trade in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published, without the prior consent of the publishers.

Designed and typeset by Cinnamon Press. Cover design by Adam Craig.

Cinnamon Press is represented by Inpress.

The author wishes to thank the estate of Louis MacNeice for permission to quote from ‘Wolves’ — © Estate of Louis MacNeice, reprinted by permission of David Higham.

ALDERMASTON

In memory of John Hoyland

One of the first Marchers

Jean

1

2121. The Broads

I come at night, in the mists, under cover of all manner of dark things. This is my way now: to arrive at a place secretly, intimating that I have done something wrong, that my work is not fit to be seen in daylight.

My work is digging up the past. I have one helper, surly and flat-faced, more muscle than brain; a student from a rich family, unfit for other activities but by tagging along behind me entitled to the accolade ‘researcher’. I can never fully be sure of my own safety—who can be now?—so to have him with me gives me the illusion of security.

Illusions are important. Try hard enough and they can become reality.

My particular illusion is named Reece.

2

The driver is twitchy. He doesn’t like being out here on the Broads, so far beyond the city walls, so late at night. The flatlands; the waterlogged edges of the Island of Britain. The driver (she names him Twitch) grumbles a lot, though she notices he doesn’t complain about the fare. They shudder along, the car stinking of a tank full of gasoline syphoned off from dead trucks a thimbleful at a time, the fruit of years of scavenging.

They pass a dog pack roaming beyond the town walls, all skinny bodies and yellow teeth, too mangy and decrepit to be any sort of a threat; but Reece cranes his head until the town is out of sight. He picks up his screen, watches the connection fade and die, sighs, drops the screen on his lap.

After half an hour of silence, Twitch stirs into life. ‘You don’t know who you’ll meet out there. A little lady like you.’ He cranes his neck and his eyes sweep Reece, but if he has questions about why an old woman should choose such a travelling companion, he does not ask. He clicks his tongue and lapses into silence. A moment later his fingers go instinctively to the radio, twitching at the dial, finding only crackles and sweeps of air.

A half hour more and the car halts. Darkness and the rattling wind.

They unload, Reece heaving her small knapsack onto his wide shoulders and carrying the other necessary things under each arm. She looks out at the grey mist and the darkness, and the little car—despite its loose windows and grumbling driver—seems a warm and living thing, throbbing with black-market gas in its veins. It roars away, and there they stand on the empty road, she and Reece; Reece too stupid to take any action beyond holding their things, too shy to ask her what to do. There are lights in the distance. She suggests the obvious. They head towards them.

She is getting too old for this. The Broads are just that, broad and flat, and the wind scythes across them. She is wearing a thick padded coat over vests and other layers, but these aren’t enough to protect her thin skin and flaking bones. The mist is so thick that she can’t see her feet, and Reece—tramping ahead of her—is soon reduced to dark shadow and squelching footsteps.

‘Reece. Reece, what are you doing, idiot? Can’t you see I can’t keep up with you?’

He grunts an apology, turns and waits. Oh, she would rather be alone, far rather, than burdened by this lumbering reminder of her own fragility, this Boy-Man. But things are what they are. She can carry very little by herself, or not without great effort.

They continue side by side, their breath coming and leaving in unison, no words desired between them. The ground is stony and wet. They are very close to water. She can’t see it but she can hear and feel it, the looming immensity of it, the dull lazy lapping. Water soothes her, mostly; she doesn’t fear it the way others do. However, in the dark it is dangerous, and she is not a fool. She grasps the top of Reece’s arm. He flinches under her touch, but the gesture must have surprised some inner decency out of him, because he turns and asks gruffly, ‘You alright, Professor Van de Volk?’

‘Jean. Call me Jean.’

She takes his silence as non-assent.

They trudge towards the small light. She smells the water and guesses it is thick with mud and decay, choked with algae blooms and other slimy things. She has no idea what: she is an historian, not a biologist. Colleagues could tell her: Hopkins with his shiny suit and his fascination with eutrophication, the choking of waterways with algae, the draining and cleansing of blooms. A more lucrative field than hers.

They are almost at the house. Reece—her security!—falters and hangs back. Really, what use is he? There is nowhere else for them to go, the town is too far to walk back to tonight; besides, it has too many dogs circling it, and even the decrepit ones might bite. And they can’t spend the night out on the Broads: temperatures plummet after dark. If they are to be stripped of their belongings and killed once they arrive, let it be so. She is too tired to care.

She strides towards the door and raps on it with her sharp knuckles. Beside her, she hears Reece’s breath come hard. She gestures for him to step back. He may be afraid, but his size makes him threatening and she doesn’t want the occupants of the house to attack because they anticipate danger.

The door opens. She sees an eye, blue and watery. It belongs to a woman, though it is difficult to tell: on the drowned edges of Europe both men and women have taken on a pinched, hard look. The rest of the face is in shadow.

A whisper. ‘Who is it?’

‘Professor Van de Volk. I wrote to you.’

‘Yeah, that’s right. You did so. You have the papers? Identity, like?’ The voice is nervous, placating.

‘I have this.’ She pulls down her hood, showing her crumpled face and her white hair. ‘You’ve seen my picture, haven’t you?’

A pause. ‘Yes, yes. Seems alright.’ The eye focuses behind her, narrows. ‘And him?’

‘My helper, Reece. I need him, travelling as I do. You understand.’

A nod. The door closes, there are whispers. Bolts are drawn, keys unlocked. The door opens a crack. ‘Money first.’

‘Of course. Always money first.’ She hands over the agreed amount. The door opens further. ‘Please,’ she says, weary. ‘Can we just come in?’

‘Yes, Come in out of the dark.’

3

2055. A Memory of digging

Why the digging, why the fascination with rooting up the past? Most people would prefer to forget.

I remember this one time in my father’s back yard, a sunny day so soft and perfect it hardly seems real now—not in these drab days—but I lived it, so it must have been true.

Home. Our yard. My father was a man with his own obsessions, mostly centred on books—the old kind, paper and leather bindings if he could find them, and titles embossed in gold—shelves and shelves of books, and a big study with books spilling over the desk and onto the floor, and a perpetual air of disappointment hanging over him, a knowledge of being undervalued by the world.

My mother was from New Orleans. She was a woman with tastes and expectations beyond my father’s means, or so I believed then, and the belief comforted me. She left us both when I was three years old. My father never spoke of her, though I had the misfortune to be her spitting image and thus the inheritor (in his eyes) of all of her sins. Mostly, I did my best to stay out of his way. Not that he was a cruel man, or did not love me—he loved me, I guess, in his way—but he had his own ideas of how children should be, and females in general, and I didn’t match up to those. We spent little time with each other apart from at mealtimes, and when he spoke to me then it was to mutter rules, or to express irritation if I forgot them. ‘Jean, don’t chew,’ he’d say, and I would pause, my mouth full, wondering how I was going to swallow my lumps of potato down whole. Once he’d said his piece, he’d generally hunch back over his own meal, shutting me out of existence, his knife clip-clopping on the plate, and I would take my chance to work my jaws quickly, as quietly as I could, and swallow a tiny bit at a time.

Anyway, I was in the yard after supper this one day. I guess it was July, the beauty of the evening making me doubt my memory, because were days ever so perfect, clouds so pink, daylight so heavy with gold? I’d gone out to look at shadows and sit in the dirt and listen to crickets. Our house was lovely, a 1930s beauty with cracked mosaic tiles on the floor and little nooks to hide in. My father had a porch swing and he’d sit on the swing on those summer evenings and drink something out of a cool glass with a sheaf of herbs sticking out of it, as content in his way as he ever could be. He had a beard that was going greyish, and wore little round glasses and had wrinkles around his eyes, and when I dared a look at him, I saw the habitual annoyance and frustration in his face stripped away and an unguardedness exposed underneath, a rawness to his disappointment which I couldn’t understand (I was a child) but which I liked better than the wound-up tick-tock of his public face. In simple terms, he looked sad, I guess.

He was on the swing above me and I heard its creak, creak, and I heard him sipping his drink, and I felt safe and sound and my mind was wandering far away. There is comfort even in the sight of an oppressor, which is how I thought of my father much of the time. I was squatting in the dust, wearing short pants and a big grubby old vest (a hand-me-down of his) and I was scraping at the dirt with a stick. Our yard was scruffier than that of most of the neighbouring houses, with big old weeds growing at its edges and mounds of dirt which I’d shaped with my own hands, and in my mind these mounds were houses and castles and mountains and sometimes lakes I made out of lemonade which dried into sweet-smelling mud. And now, because of the time of the evening and the golden heaviness of twilight, the mounds were full of voluptuous dark shadows and these were wonderful to me.

Our neighbourhood was a good one, just on the cusp of turning bad. A couple of nearby lots were empty, but the inhabited ones were neat and obsessively tended, and while people talked about moving away, that talk was mostly followed with a laugh and a catch-throated joke, the claim that things would surely turn around. And the heat grew, and the dust rose, and people got mad, not at their neighbours but at nameless others who they figured out must somehow be to blame.

I watched a bug crawling up a dirt mound and followed it with my stick, not poking it but encouraging it to move faster, which it did, my heart beating hard and my mouth watering, the little bit of cruelty tasting good. I watched the bug speed up, running in crazy circles and then scampering down the hill towards the lemonade lake. It reached the lake and crawled into a tunnel I hadn’t seen. The earthworks around the bug caved in. Where had the thing gone? Could it live underground? I had questions.

Creak, creak, went the swing.

I began to dig with my fingers. Oh, I’d find out where that thing went. I couldn’t see it so I dug further, under the sticky lemonade mud to where the earth was dry and cracked and under that to where it became dark and damp again, raising a mountain of earth, my fingernails black, my whole fierce little being puffing with effort, wanting to pee but not wanting to go until I’d found that stupid old bug. I wiggled on the ground and my fingers hit something hard.

I took my stick and moved it slowly, probing, breath rasping. The thing I’d hit was too smooth to be a rock. I began to dig in a more concentrated way, focussing on shifting the earth around the hard shape, hunched over the hole so that my father couldn’t see what I was doing. I saw a glitter of gold. I cast the stick aside and used my hands again, pinching a little piece of dirt away at a time until my nails scraped on the smooth gold surface. I levered my fingers around the edges and eased it out. A box with a lid, shut with a catch. Pure gold, I thought then, though I guess it was probably brass. I tucked it inside my vest. Glancing at my father sitting above me, I began to fill in the hole. I spread the sand wide to mask all signs of digging. When this was done to my satisfaction, I climbed up the steps to the porch and walked past my father with my arms folded across my middle, the box pressing onto the bare flesh under my vest, nuzzling my stomach and my bursting bladder. Oh, the lovely cold of it.

I ran to the bathroom and relieved myself, sighing with pleasure. Then I grabbed a knife from the kitchen, scampered up to my room and tipped the box onto my bed, dirt and all. I eased the knife under the catch. It broke easily. Inside was a necklace of different coloured jewels. I held my treasure up to the window, and the jewels sparkled in the light of the just-risen moon. They were made of glass, I know that now, but I didn’t know it then: then, they were priceless, astonishing, buried there especially for me under our yard by my mother, for her own darling daughter.

Whom she must have loved most of all.

4

The family are dredgers. They make their living cleaning choked waterways, draining silt, cutting reeds and managing the weed beds. Consequently, the water around their house is clearer and purer than in other parts of the Broads, and for their pains they are rewarded with the chance to fish a few bloated perch from the flooded canals, and cut peat and sell it as fuel in the town, alongside the fish. It’s not an easy living; but they get by, or so it seems to Jean, her eyes sweeping the neat parlour. The little stone house has been in their family for centuries, the dredgers say. They, and a few stubborn others on the Broads, refuse to leave, though the flood waters draw nearer every year.

They are shy and welcoming once they have gotten over their fear. They usher the travellers in, bolting the door behind them. Reece looks around, cumbersome in the tiny house, clasping his hands as if he’s about to start some business meeting. Jean shushes him, though he has not yet begun to speak.

The dredgers feed them and don’t ask questions, showing a lack of curiosity which Jean, in her exhaustion, welcomes. She and Reece sit at the kitchen table. Their faces grow hot and red from the peat fire.

The couple are younger than they appeared at first sight, in their late twenties maybe, or thirties at most. Jean observes a discarded wooden toy car and a blanket on the floor, and assumes a child or two. The parents’ faces are lined and shiny pink, weathered, spiders’ webs of wrinkles fanning from their eyes, she guesses from squinting against all that wind. After dinner, the woman sits in shadows near the fire, her face turned away as if ashamed of her faded looks. The man is friendlier. He stays at the table and drinks barley coffee with Jean and Reece.

‘You come a long way,’ he says, by way of opening the conversation. ‘We didn’t think as you would come. So far, and so little to see.’

‘I hope it’ll be worthwhile.’

‘Digging, you said?’ He raises his eyebrows, trying not to show too much interest.

‘That’s my job.’ She gives him a small smile, playing the harmless old lady.

‘So far, to dig in a bit of old mud.’ He cracks his knuckles.

‘We’re glad you came,’ interjects the woman. ‘We didn’t believe it. All that money.’ She shakes her head.

‘We’re glad of company too, like,’ adds the man, glancing at his wife.

Jean watches them both and runs her fingers through her hair. She can feel it standing on end in the heat, a silvery halo. She doubts very much the dredgers are glad of their company. ‘I’m looking for a village called Alethorp. Have you heard of it?’

‘No.’ Without hesitation.

She takes out her map and points. ‘Here. That’s where it would have been. Around here. Before the flood. See? The coast was further out then.’

The man and the woman exchange glances. ‘No. Nothing by that name.’ The man looks closely, his finger lingering over the spot which Jean had indicated.

‘A hill,’ she insists. ‘There should be a long flat hill, well, a slope really, not high. It used to rise up to sand dunes a mile or so from the shore, but the sea is right behind it now, I would guess.’ Her heart flutters, and she tries to keep the urgency out of her voice. ‘That’s what I’m looking for, where I want to dig. Do you know it?’

‘There’s a hill,’ the dredger man says, uncertainly, and he glances at the woman again. ‘Just before the sea. But the flood—’

‘You’ve been there?’

The man grimaces. ‘I don’t have no reason to go.’

Jean notes this is not quite the answer to her question. ‘We could walk to it, do you think? Is the water low enough?’

‘You see, there are other places. Further from the water, right? The flood, see—’

‘How far have you been up that way?’

He points vaguely to an area about a mile from the hill. A muscle that has tensed in Jean’s jaw loosens. ‘How long does it take?’

‘Five. Six miles. So, maybe, an hour, maybe two.’ He frowns again. ‘But you won’t find nothing. Water, and then more water, and then the sea. That’s about it.’

Jean looks out of the window at the inky outline of the marshes. She sees a long flat line, the sky a faintly lighter line above, the heavens dotted with stars; all of it fading into immeasurable distance. Patches of wet everywhere, mirrors to the moon, everything damp and decomposing and descending into the sea.

Reece slurps his coffee and yawns. The woman jumps up. ‘I’ll show you where you’re sleeping.’ She colours, stuttering over her next sentence. ‘We didn’t know you was two, did we? So, you’ll have to sleep in baby’s room,’ she says, looking at Jean, ‘If you don’t mind, like. Sorry. We have one room for him.’ Indicating Reece. ‘And we’ll sleep downstairs, here.’

‘I’m sorry to put you out.’

The man shakes his head. ‘The fire’s warm, isn’t it?’

‘We may be here for a week. Maybe more.’

‘We’ll be out most of the day. Working. And you—’

‘Yes. We’ll be working too.’

He nods and rubs his blunt fingers along his face, a gesture redolent of deep weariness. ‘But— I don’t know. There’s the water that way, and the mud flats, see, and most people are afraid of those.’ His eyes shift away from Jean.

Reece puts down his cup and blurts, ‘They said there are men out here, people who’ll kill you, who’ll cut your throat when you’re asleep or something. That’s what they said.’

‘Reece.’

The man shrugs. ‘Dog packs wandering on the marshes, bogeymen who’ll slit your throat, vagrants and migrants ready to rob you and that. Is that it?’ His hands trace the patina of the table. Rough fingers, smooth wood. ‘You afraid, are you?’

‘It’s just what they said.’ Reece falters, awkward.

‘They think they’re better off in the town, ’cause they’re further from the water. The dogs stay nearer town, mostly, matter of fact. More food. It’s rare they come this far. Though some do.’

The woman flaps her hands, agitating the air. ‘You’re tired, must be. Will I show you where you’re to sleep?’

A cloak of immense weariness wraps itself around Jean. Faces melt, the walls and ceiling move closer together. The orange glow of the fire expands, a living thing. Who is to know whether this harassed couple don’t keep knives to slit strangers’ throats? She’s heard of worse, and these two are nervy and browbeaten. Ah, well. So be it. She flashes Reece a glance. ‘Yes,’ she says. ‘We’ll sleep now.’

She stumbles as the woman leads her up the stairs. She feels her hands, small and much stronger than she had expected, hard against her back. ‘It’s alright, babe,’ the woman whispers, as if Jean really was a baby. ‘It’s alright. You can sleep.’

5

2060. I am twelve years old and about to grow up

My name is Jean Van de Volk. I am one of the few who can still remember.

People tell me—more frequently now than ever—that I have been lucky. I spent the worst part of the second American dustbowl sheltered from things that others lived through: the violence, the dislocation, the awful dread. News of it filtered through to me only elliptically, became background music for the most part, incidental to what, for me, was the main story. My life.

Later they would call it the Crisis, but we didn’t know, then, that it was a crisis that we were living through. At what point does a series of unrelated events become a crisis? A crop failure one year? Drought or disease the next? Brownouts were common, but that was OK: they were easy to get used to, and it was kind of fun to light candles at home and cook on gas. No-one told us that the brownouts were signs of an energy system creaking and breathing its last, or that crop failures one year might mean hunger down the line. Food could be imported, could it not? And for those who had money, there would always be the things that money can buy. We scorned the crazies who saw it all as one big plot, and as for the uneasy sense that things were out of kilter—well, even that can become routine, because living through it, all kinds of stuff becomes normal, just as any life is normal for those who live through it.

Everything before my twelfth birthday, I look on now as a golden age. Despite, or maybe because of, my father’s lack of interest in me, I had a freedom which I was only able to appreciate once it was gone. I learned to exist in a way which seemed not to bother him: I played in the yard, I dug, I wandered around the house while he worked and read and sighed. Alongside my physical freedom, I had a certain freedom of the mind which I did not understand at the time, but which stemmed from my father’s vituperative opposition to what he called brainwarpers: that is, sources of knowledge which he did not control. ‘Do you want to be a zombie, Jean?’ He’d ask. ‘Like those other kids? You want your brain cooked till it melts?’ I complained, but only faintly. As with other things in my life, I feared what I lacked.

As time went on, I noticed that my father seemed to blame me less for the failings of all womankind, and recruit me instead as an ally; someone always on hand to hear out his complaints. He had no-one else, I guess. I encouraged this tendency, seeing quickly how much to my advantage it was.

I used to walk to school along the dusty track that led up the hill from my yard. Each year there were fewer students, and by the time I reached twelve, my breasts budding awkwardly and my legs suddenly too long, there were only ten of us in a single class, overseen by a battered and world-weary teacher who wore her hair in a bun (of all things!) and had a nervous tic in one eye; a creature ripe for my derision. I gathered stories about her for my father, carefully selecting the ones which would please him the most—or raise his ire, which amounted to the same thing.

‘Dad, we did poetry today. You know what? She’s never even heard of Tennyson.’

He put down his book, a soft measured impact on the table. ‘How so?’

‘I quoted from ‘Crossing the Bar’. Everyone ought to know that one, right?’

‘Of course. Tennyson’s hope for the end of his despair in death.’ Dad stood up and began to scan the bookshelves for the right volume, his fingertips stroking the spines.

‘Well, she didn’t know it, Mrs Teale. She didn’t have a clue. You know how you can always tell when someone’s bluffing?’ I watched my father’s back carefully, measuring his contempt in how tightly his muscles bunched.

He stopped casting around for the book and sighed. ‘Oh yes, I know. I think sometimes there’s no hope for us, Jean.’

‘I told her I was surprised she didn’t know it, and she took offence, and said I should read American poetry, if I was going to read any at all.’

‘And?’

‘I asked her which of Emily Dickinson’s works was her favourite.’

He laughed. ‘She didn’t answer, of course.’

‘No. She told me they were all her favourite.’

‘Delectable, Jean.’

‘And to stop being a know-all.’

‘After great pain, a formal feeling comes—’ My father closed his eyes, reciting. He turned and gave me a wan smile. ‘Well, well, Jean. What is to be done?’

And so it went on. We drew closer in our delicious angry alliance and I thought that nothing would ever change, and the days would stay long and golden and the shadows on the sand would never reach me. And it was so, until the day my father told me we had to leave.

I was in the yard, burying my own feet, looking on with satisfaction at my trenches and mountains and tunnels, all of which had grown vastly more elaborate since those first days of digging (naive early works, I thought of them, hardly worthy of the name). ‘Huh? What did you say?’

‘We’re moving, Jean.’

I dropped my trowel and stood up. I’d had an idea, a while back, that I wanted to grow something, so I spent my free days poking seeds into the earth and tending skinny white shoots with enormous care, though they so often shrivelled in the sun. ‘Well, that’s dumb.’

‘Don’t speak like that Jean. It has a tone of mockery.’

I stood up straighter. ‘But it’s a joke, right?’

‘How many children are there in your class now?’

‘Why, ten of us, I believe.’ My hands on my hips. I thought for a second. ‘Though the Carters left a month ago. So, I guess that leaves eight. I don’t mind. It’s OK.’ The truth was, I loved my school. I’d been there for the entirety of my remembered life, and I had stayed on because our high school had closed already, and my father said he could teach me anyway. For the last couple of years I had taken on an informal role of assistant teacher, taller than all the other children by a head, learning the stuff I needed in advance of lessons for the older kids (just a year or two behind me) and helping the younger ones with the basics of reading and mathematics, an easy task which reinforced a sense of superiority I had, I suppose, absorbed from my father. The curriculum was a quirky one, devised mainly by myself (the hopeless Mrs Teale having pretty much given up) with a few additional touches from Dad. I taught classical myths, the reading of cloud patterns, the names of trees and the periodic table, and whatever else happened to interest me. Over the years I had become quite the polymath.

‘Doesn’t the schoolwork bore you?’ he asked. ‘It must be repetitive, teaching the little ones.’

‘You teach me, I teach myself. I’m not bored. Not at all.’ His questions were giving me a weird feeling deep in my stomach. I put my hand there to keep it down.

He drew his own hand across his forehead. ‘Jean, look around you. I mean truly, look.’

I looked. A heat haze was rising. The far end of the street was rippled and opaque. Across the road from us was the neighbour’s house, long boarded up. Drifting fingers of sand clogged up the once-neat path and reached under the door. I turned and looked up the hill. Every second house was abandoned. Rising towards the empty lots, in little rippling dunes, was the sand. It rose so high that it made a second hill on each side of the track. Somebody swept the track every day, so that the path, once level with the bank, now tunnelled through it like one of my very own creations.

‘What do you see, Jean?’

I blinked. ‘It’s OK. It’s all OK.’

‘It’s dead, Jean. It’s a cockadoodle mess. There isn’t anything here. Anyone with any sense has left a long time ago.’

‘So why didn’t we leave already?’ My voice took on an accusatory tone.

‘I had my job. I don’t have that anymore.’

‘Huh?’ My father hated his job—and like other things he hated, it sustained and invigorated him. He spoke constantly of the dwindling of the department, of the trouble he had getting gas for the long commute, of how he was slighted and despised. The song was so old I’d stopped hearing it, but it was hard to imagine him without it. The sun hazed in my eyes. I shook my head.

‘Do you remember your aunt Julianne?’ he was saying. ‘Your mother’s sister?’

‘I didn’t even know she had a sister. You never said that.’ I wanted to accuse him of something, and this lack of a sister seemed good ammunition. ‘You never tell me anything.’

‘She’s put my name forward for a job in an elementary school. It’s on the coast. You’ll like it there.’

‘You’re going to be an elementary school teacher?’

He put a clumsy hand on my shoulder, and I realised, with a shock, that he was trying to sooth me. His lack of outrage acted as a dreadful blow.

We packed up and drove across the desert.

It took us three days, squashed between a silvery line of trucks which snaked into the distance in both directions as far as I could see. It seemed like everyone wanted to leave somewhere, and I thought it strange that some of the trucks were headed to the very place we’d just left. Other trucks had been abandoned a long time ago, and were dust-covered ruins along the route. I thought them sad, those lonely hulks by the side of the road, and I stared at them for a long time as we crawled by.

We stopped for the first night in a motel in the middle of nowhere. One room with twin beds. I looked at Dad’s broad back as he took his shirt off, curious at the dark hairs that fuzzed up on his shoulders. He stretched out on the bed and turned away from me. I lay under one thin sheet sweating and wide-eyed, and once he had fallen to sleep, I listened to his snores and the strange tinny sound of the screen through the wall. Eventually I turned my eyes from his bare skin, the big mound of his body way too close, the damp sweet smell of him acrid in my nostrils. It was hard to sleep with his bulky adult body so near, and me with my new breasts tight under my shirt, and I got a pain between my legs and pressed them together hard and tried to think of the different names of clouds, while my palms slicked over with sweat.

The next day we didn’t talk except when we stopped at a gas station for sodas. We sat next to each other on the asphalt under the shade of the building and I squinted at the line of trucks. ‘Where’s everyone going?’

‘To the coast, I guess you could say. To the water. Not everywhere is like this, Jean.’

‘To the water?’ The word made me thirsty. I swigged my soda.

‘To the water. To the sea.’ A breeze rose up and his hair fluttered.

I had never seen it. I said it to myself. The sea.

The word contained immensity.

On the second night we slept in the car by the side of the road. Even with the windows wound down and the night breeze wafting in, it was fearfully hot. A truck driver who had stopped nearby passed us water. We thanked him, embarrassed by our pitiful lack. Even so, despite our thirst and the heat and the boiling, angry sky, I liked that night better than the dreadful one in the motel. I lay on my back across the rear seat and looked at the sky streaked with stars, and I felt peaceful and alone under the vastness of everything.

Early evening on the third day we arrived at Aunt Julianne’s.

For a couple of hours, the air had gotten lighter and less laden with heat. We drove with the windows down, me in the front next to Dad, my hair blowing across my face, Dad tapping out a tune on the steering wheel; some old, old stuff like jazz or something. I put my pink sunglasses on to shade my eyes and I looked at my Movie Star eyebrows in the side mirror (newly plucked, a skill I had only just acquired) and I smiled at myself, my teeth clean and pearly white.

The road widened and became smoother. Trees sprang up, feathery palms mostly, and a few others too: Japanese maples, gum trees, birches. I stared at their spindly trunks and their small shivering leaves, their shadows like slender men on the long open road, and I mouthed their names as we rode by.

Sea grape. Cedar. Mahogany.

There were more cars on the highway—bigger and newer than ours—and fewer trucks. As we got nearer to the coast, I craned for the sea, sensing it—there was something fresh in the air, a scent of ozone—but never quite seeing it, though the road got so wide that it felt like a playground ride, and we swooped along, laughing. I’d seen my father smile so rarely in my life that I had to keep sneaking peeks at him to be sure.

We neared Aunt Julianne’s place and he sobered.

Aunt Julianne lived in a gated compound a mile or so from the sea. It was called The Maples. I knew that because the entrance was a big arched door with a sign above it. Dad had to show a security pass to get in. The door opened silently and shut smoothly behind us. Apparently, my aunt had arranged all this, the passes and whatnot. She was a nurse, Dad told me, working for one of the big energy firms with perks and benefits which included healthcare and a small apartment, though she wasn’t strictly a first-grade employee: she counted as ‘service’ to the real workers, but that didn’t matter, my father said, even the cleaning staff had their own little places on the far edges of the compound. The compound contained shops and all kinds of amenities, so there was little need for employees to ever venture out, and I guessed they didn’t, with that gate sealed behind. There was also a junior school, and that was where my father was going to work. I myself would be going to the senior school after the summer, along with other employees’ children.

We drove across the greenest lawn I had ever seen. I leaned out of the car to look, my sunglasses perched on top my nose, forgetting I was a Movie Star. The lawn was fed by arching sprinklers which created rainbows every few feet. I held out my hand to them, but the shimmering fountains of light passed through my fingers.

Dad stopped the car. Everything became quiet. I stepped out. The grass was so springy under my feet—an inch long and thick as fur—that I took off my sandals immediately and curled my toes around it. I had an impulse to kneel down and touch the springy green stuff, and I would have done it if I hadn’t heard Aunt Julianne’s voice.

‘So, this must be the famous Jean?’

I looked up. There she was: a woman with a round face, little blue eyes and big curly hair. Kind of old-looking. And disappointing. She had no grace, no special features. She was wearing some kind of a pink top that floated around her arms, and had a load of rings sprouting like warts on her plump fingers. She was nothing like the picture I’d imagined: I’d thought my mother’s older sister must be slim, and haughty—why else would she have kept herself hidden from us?—and beautiful, of course. As I dimly remembered or imagined my mother to be.

I stared at Julianne as she tripped her way to my father, her blouse floating around her fat old arms.

‘David. It’s been such a while.’ To my astonishment, they embraced.

Then Julianne approached me and did the strangest thing. With a soft little flick of her manicured finger, she first stroked my cheek, and then pushed my jaw tight shut.

‘Flies will get in,’ she said.

6

Her mind races into the small hours.

Little nagging worries—do they have the right equipment? will it work?—mix with larger fears: of the dark, the unknown, the strange midnight sounds. Outside, generators hum. Night birds squawk and cry. River water laps close to the house. She mutters, How close? How many months or years until this place, too, is swallowed by the flood?

A fretful sleep on a narrow camp-bed. Each time she turns, her heavy quilt seems to dislodge, leaving parts of her body exposed to the air, her shoulders and neck twisting unpleasantly. Sheets ruck up under her feet. The baby’s cot is next to her bed. He is not a new-born infant; more than a year old, or so she guesses. She has limited knowledge of such things as babies’ ages, no time for thoughts of nursing and coddling and cooing. At times during the night, she turns her head and watches the small hump of the child’s body rising and falling with its breath, its arms stretched above its head. Mercifully, though it snuffles and gurgles, it does not wake.

She has disjointed dreams of raccoons and rodents like the ones which had once infested their trash back home. They are climbing over the sand and gullies of her creations, and then a switchback to the long ride across the desert and Dad sitting beside her and smiling like he knew something (what?) and Jean annoyed at him for entering her dream so matter-of-fact, when she had been content not to think of him for years. Then, somehow, Twitch the taxi driver appears, riding round and around the cottage and shouting that he can’t take her, while human-sized raccoons stare out of the taxi windows, their black paws splayed on the sills—until a baby sun spreads sticky fingers of marmalade light over the Broads and she wakes.

Her skin is stretched and puckered. Such an empty place, and the damp already seeping into her bones.

The creaks and groans of stirring. The indignity of age.

She swings her skinny legs out of her bed, feels for her neck, and finds it intact. Beside her, the child’s cot is empty. She takes a look at the mechanical clock by her bed. Five a.m. Behind the clock is a note she’d discarded the night before. It is from Hopkins: a man in love with the capital letter.

Jean,

You have not—repeat NOT—secured permission to explore the Edges. You have a provisional visa only and limited permission for preparatory DAY trips only to assess safety and viability of research—I repeat, DAY time only. I want you to be clear that I shall bear no responsibility for your behaviour, nor will I be inclined to look favourably on any further funding if—

She picks up her coat, which is hanging over a wooden chest, and wraps it over her pyjamas. She goes to the window. There is a layer of veined ice on the inside, snowflake tendrils reaching to the centre of the glass. She puts a fingertip to it and a corner of ice melts. The damp air is warming rapidly. It is so on the Broads: icy nights and humid days, whispers of mosquitoes, of tropical creatures returning each summer.

She squints through the gaps in the melting ice. The sky hangs over a landscape of marshes and sluggish rivers, squat trees like pot-bellied old men talking in furtive clumps. Reeds and bulrushes are the only other verticals. A patchwork of dull greens, earth colours, pewter and grey; muddy water choked with algae blooms. Below her, the dredgers’ garden is neat and well kept: an acre or so of enclosed land, with rows of vegetables, a hen coop (she had surely heard, then, not imagined, a cockerel crowing at first light) and a tethered goat, which would account for the milk they’d drunk. Chestnuts and oaks and beach trees surround the garden, some showing their first green buds. All is earthy and fruitful, and Jean pictures seeds swelling under the ground. The waterways immediately surrounding the land are clean, bringing a healthy hue for a mile or so before everything becomes choked and sickly green.

She is heartened by all this.

She tears up Hopkins’s note and shuffles downstairs in her bare feet. Their hosts are sleeping on a bundle of blankets on the floor. She creeps past them and hears a little peal of laughter, which shocks her at first until she sees the dredger’s child squatting in the corner. He is watching her with large dark eyes. He toddles forwards, sways, falls, and begins to cry. Stupid infant, she thinks. The dredgers wake, stirring uncomfortably. Jean tuts, scoops up the child and carries it, squirming, back upstairs, where she scolds it into silence and stuffs it into bed.

After the necessary irritations of breakfast, of seeking directions and goodbyes, she and Reece begin to plod over the marshes, their warm breath clouding around them. The day is damp and misty. Low sky and clouds, and plenty of time to think.

The first problem: she has only a rough idea of where they should start digging. The records give her some clues, but many landmarks have been washed away or altered by the flood, and she will have to rely, to a certain extent, on guesswork.

She is searching for a village called Alethorp. The hill which the dredger pointed out last night is called, apparently, Alltop. Good enough—in fact, very good. Last night she looked through her papers and found a reference to Alltop Hill, more often The Top: ‘A long mountain with good pasture and common land for grazing.’ And nearby, a village, some ancient earthworks, and a church built halfway up, and beyond it, long dunes sweeping out to the sea.

It could be the right one. It must be right. She swallows excitement like spit.

Next problem: experience of previous digs tells her that those who buried time capsules were vague when it came to instructions. They expected the future to know their own minds as well as they did, and to be as familiar as they were with their own habits and preferences. Jean cannot be completely sure anything is buried there at all, a detail which has not escaped the eyes of her funders.

Her request scraped through as a budget footnote within a larger funding application, one of sufficient interest to be approved. She is therefore undertaking her work as part of a study of 19th Century waterways and flood management which, she is assured by the lead researchers, promises great lessons for holding back Europe’s present tides. The main group is based in Norwich. They have buried themselves in what is left of the city’s archives, hunkering down amidst the perceived safety of crowds. Their task is more or less useless, she believes: if the 19th Century held any great lessons, why did the floods reach so far and fast?

Useless or not, their endeavour left enough money over to fund her obscure little project. And so, here she is, on the dirty ragged edges of Europe, hoping to retrieve a different kind of history.

At first, the capsules unearthed themselves. They washed themselves up on mud banks, dislodged by freak tides, emerging ashore miles from where they’d been buried. In the second American dustbowl they were regurgitated by the desert, and for a while they were objects of mild curiosity, emblems of an optimistic past which had imagined a happier future. In the early days of her research, Jean had found a few capsules through dealers and junk shops and dusty corners of the Internet, which her academic status allowed her to roam more or less freely once the rotted cables had been restored. It didn’t take long before the collectors and sentimentalists and junk shop owners lost interest. The uselessness of the objects meant that for the most part they were quickly discarded, along with the rest of the world’s useless things.

She, however, persisted.

The craze for burying capsules was at its height in the latter half of the 20th Century—the 1960s and 70s—and her greatest finds were from this era. She envied them, the buriers, the children of happiness with their tenderly-composed love letters to the future. She organised their offerings fondly: the photograph albums of town councils, the dated newspapers, the cherished local products, the steel and the plastic and the pottery. Their offerings to memory became her research. She mapped them across Europe, from the war-ravaged Caucuses to the submerged remnants of the low countries, following the craze for capsules as it passed from town to town like the Spanish flu. She became a connoisseur of the unique find. The only capsule she ever unearthed in Poland was a particular treasure, full of doll’s clothes and scraps of poetry and tinned food. The very last recorded capsule she knows of—another treasure, one she loves dearly—was buried in a town in Utah in 2027. It contained beer bottles, pornographic magazines and someone’s old cellphone; the contents a strange echo of one of the first capsules: this had been buried in the 1890s by an American railway worker, and contained a newspaper, playing cards printed with nude women, and a bottle of whiskey.

Now, she is on the trail of a capsule buried in 1958, and intended for opening on 30th March, 2121. That is, in three days’ time.

A flat white sun casts a milky light over the waters, picking out long-stemmed bulrushes. Reece carries their equipment in a large backpack: a metal detector, sonar, and some workman-like tools, a pickaxe, a hammer. She carries a GPS and—more trustworthy—an ancient paper map and a compass. She fingers the compass, checking the dancing needle while Reece—her Sancho Panza—trudges silently beside her. Ahead, a crowd of starlings rises out of the mist—loops and whorls of them—a thousand black flutterings. ‘A murmuration,’ she says.

‘What?’ asks Reece.

Neither of them has spoken for a long time, and her voice has interrupted the tramping of their feet. The clumps of yellow grass they have been walking on are thinning, the water around them deeper and more treacherous. She stops amongst the bulrushes.

Reece stops too.

‘A murmuration of starlings. The birds. It’s what you call them when they’re all flying in a group like that.’

Reece grunts, a sound to set her teeth on edge. What had seemed an advantage when she hired him—his sullenness—is beginning to grate. She sighs, and asks, ‘Where do you grace from, Reece?’

‘Eh?’

‘Where are you from? Who are your family? Who are you? Fair questions, don’t you think? I suppose we are spending some time together, so we may as well know these things.’

‘We’re talking about homes and families now?’ He rounds his shoulders.

‘It’s a topic. One to begin with.’

Silence.

She starts to walk again. He follows. Their boots splash in the mud.

A whole minute later he says, ‘It’s just, you never asked me any questions like that before.’

‘I was making conversation. Have you heard of that?’

Another pause. Lone birdsong, full throated music pouring into the air. Then:

‘Palo Alto.’

‘What?’

‘Palo Alto. That’s where I’m from.’

She pictures it. A gated town, temperature controlled, palm trees and servants who think themselves lucky, desert blooms and irrigated soil. Poor Little Rich Boy. She knows the kind. ‘Of course you are.’

A weak tremor passes over Reece’s face. The starlings wheel and whistle in the sky, showering towards them like so much rain.

7

Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament, Archives: Memories of Aldermaston

Ida Washington was amongst the first of the Aldermaston marchers. Now in her eighties, she recalls the firm sense of purpose of the first march. ‘It was a lovely atmosphere,’ she says, ‘there was a great sense of solidarity. We linked arms and some people cheered us along the route, though there were some hecklers too, but we didn’t mind, as they were very much the minority. Most people were marvellous. We were fed all along the way. People gave us places to stay, church halls and barns and such like, it was wonderful how kind everyone was. We played music and sang. We had Ken Colyer’s jazz band, skiffle groups and church singers. It was tremendous, really, it was something you got swept along with. I think it’s marvellous that we all stood for something, and I am proud to have been one of the marchers. We were thoroughly convinced that people would listen to us.

‘My friends and I wanted to commemorate the occasion in some way, so we had an idea beforehand that we would bury a ‘time capsule’ which represented all of our thoughts and ideas, to be opened in 2121—a date as far into the future as we could possibly imagine. We were staying in Norfolk near a village called Alethorpe, on a little holiday a week before the march, and we buried the capsule in a graveyard there, I remember the date distinctly, it was the 30th March 1958, and we buried it just in the shadow of this marvellous old Saxon church which was halfway up a hill, very pretty and quite a landmark. We were convinced that, when the capsule was opened, the people of the future would have created a much better world than the one we presently live in, and it was our way of leaving something of ourselves behind. We firmly believed that everything we buried would seem most primitive and strange to those dwelling in the future.’

She carries it in her pocket, a dog-eared pamphlet she found in a city library—one of the last—thirty years earlier, and has held close ever since. She keeps it in a tin box to protect it from weather and her journeys, but each time she takes it out, it seems more fragile.

She doubts it in other ways, too. What began as certainty grows opaque the more she studies it. There are no other sources to confirm the burial. Worse, Alethorpe itself was not a living village even in 1958, a curious anomaly. And, vexingly, there is no indication of what was buried. Most capsule makers have a particular message for the future, something that signifies the place they are from, or a certain type of technology or way of life which they consider important or memorable. Ida Washington is curiously oblique when it comes to details, and in her more truthful moments Jean acknowledges that all she has to base her research project on are the faulty memories of an old woman, who is looking back at an event which must have seemed distant even in her lifetime.

She mutters as she walks. Alethorpe. Alltop