9,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Atlantic Books

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

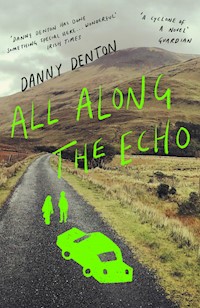

'A cyclone of a novel' Guardian An absolute marvel' Max Porter, bestselling author of Lanny 'Dancing and dodging, surprising and poignant' Lisa McInerney, bestselling author of The Rules of Revelation FIRST VOICE: Why are we listening? SECOND VOICE: I dunno, I mean, what else is there to do? Tony Cooney, a local-radio DJ, spends his days on air, talking to the listeners of Cork. They call in to tell him about overturned sewage trucks and nuisance graffiti artists, each story a small testimony to the bustle of life that goes on in the county. Off air, however, Tony is beginning to feel unsettled. His long marriage is strained, his teenage daughter is struggling with her mental health, and then out of the blue an old girlfriend gets in touch and suggests he come to visit. Lou Fitzpatrick, Tony's young radio-show producer, is having her own off-air problems. She wants children, but her girlfriend has other ideas### they've lost their beloved cat and her father's drinking is way past problematic. Which is why both Tony and Lou are relieved to leave Cork and drive across Ireland as part of a radio publicity stunt organized by a local car dealership. Their aim is to give away the Mazda 2 that they're driving, the catch being that it must go to one of the many emigrants who have recently returned home to escape a wave of escalating terror attacks in London. But as they navigate dual-carriageways and Travelodges, giving airtime and narrative to the great cacophony of voices calling into the show, the car competition transforms into a surreal quest: Tony to find his first love, Lou to find answers to impossible questions, and all the while two mysterious voices listen in, making their own estimations... A mighty tale of radios, road trips and of the noisy static of life, All Along the Echo asks us whether our lives ever add up to more than the stories we tell ourselves. Funny, warm and in the wilding spirit of George Saunders or Samuel Beckett, Danny Denton's novel is a bravura capturing of modern Ireland, one that shows us the possibilities of fiction, the nature of love and death, and what it is for each of us to be only the briefest signal in life's splendid broadcastttzchidhcmxc [static].

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Ähnliche

Danny Denton is a writer from Cork, Ireland. His first novel, The Earlie King & the Kid in Yellow, was published in 2018.

Also by Danny Denton

The Earlie King & the Kid in Yellow

First published in hardback and trade paperback in Great Britain and Ireland in 2022 by Atlantic Books, an imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd.

Copyright © Danny Denton, 2022

The moral right of Danny Denton to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities, is entirely coincidental.

The author is very grateful to the Arts Council of Ireland, who provided invaluable financial support in the writing of this book.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Hardback ISBN: 978 1 83895 553 3

Trade paperback ISBN: 978 1 83895 554 0

E-book ISBN: 978 1 83895 555 7

Printed in Great Britain

Atlantic Books

An imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd

Ormond House

26–27 Boswell Street

London

WC1N 3JZ

www.atlantic-books.co.uk

for Rachel,

across the counter in the Royal George,

at Gougane Barra,

see you in bed x

‘Let them think of what that meant, of the calling which went on every day from room to room of a house, and then think of that calling extending from pole to pole; not a noisy babble, but a call audible to him who wanted to hear and absolutely silent to him who did not, it was almost like dreamland and ghostland, not the ghostland of the heated imagination cultivated by the Psychical Society, but a real communication from a distance based on true physical laws.’

Professor W. E. Ayrton, the chairman of the Royal Society of Arts, calling for a vote of thanks to Mr. G Marconi, who had just presented his paper ‘Wireless Telegraphy’ (on the future of radio) to the Royal Society of Arts, in London, May 1902.

_________________

SLKNSSDNSLKDNSMNEQWNQWNNNA DQWEFRMHHMSDLOOFJDFDLKWEN WWWKFDFLSDPAOOTHENAKFNGF NEISNSFDNWEW IN THE STA TICthe first noise is the hum of electricity, radio in its own language, dreamed or not, and the first vision is the ghost of the receiver antenna, silhouetted against the night’s clouds, some part or echo of it blinking red at intervals. Through the dark came once the rustling, the beam of torchlight, the slow whistle of the engineer, as he fumbled and dropped his keys, as he fished for the keys in the dark grass of the field and found them, and unlocked the bolt and pulled the chain and then yanked open the gate against the long grass. The transmitter station is two squat breezeblock huts with corrugated roofs – one for signal, one for power – and the engineer had yet again to sweep aside swathes of long grass and nettle and thistle to get to the signal hut’s door and its lock, and again in the dark he found the key for that door and pulled it open, and fumbled for the light switch as his eyes clocked in the gloom the ‘ON’ lights and the signal lights of receivers and transmitters and servers and the signal dissipator and the hot pipes that still carry the signal back and forth, the signal that is clearest shortly before the dawndfmfmgkykyher bsbndfnfgnynuljhpkjlsjandcnvbnxcbaswejktykydnnfn ghturksamdsndnfnnunununuynuibbibibibibbsiwopdkfk kgkhmyntnanandndnntnykykulilipdmmgnsndflllglglyy fgtyuisasfgbhywjhmyntelgmyny

_________________

BROADCASTING SIMULTANEOUSLY on 5264 kHz + 1420 MHz…

playback:

the pale moon was rising above the green mountain / the sun was declining beneath the blue sea…

first voice:

[static] nine… five… seven… two… [static] broadcasting to all, but to nobody in particular of course… [static] they say your life flashes before your eyes… [static] but the listener forms their own image [static] the big ear listening straight out as the world turned [static] i hear them [static] and therefore i see them [static] just like this…

_________________

OFF-AIR, he dreamed that the car competition had already begun and he sat alone in the driver’s seat of a tiny Mazda, pulled into the hard shoulder of the dual carriageway, overlooking the Mahon estuary just beyond the slip road for Rochestown. And from that weather hill he could see where the seaweed shores encrusted the land, and where the city sprawled in the distance. On the opposite riverbank, smoke rose from low blocks of nondescript facilities that might have been pharmaceuticals, or warehouses, or makers of tiny plastic cylinders. And he saw the marshland, the river, the slip roads and flyovers, the castle, the docklands, and, rising out of the city’s roofstacks and steeples and aerials, the radio station’s mast. The beacon. And it was all the same, but it was utterly different.

‘COME ON WILL YOU, TONY!’ a voice boomed, and when he turned there was the giant head of a man in the back seat. Bald and bearded, cross-eyed, gaping at him.

‘I must get back to Ireland for me funeral,’ the head said.

It was just a head, filling the back seat on the passenger side.

‘I fucking hate London,’ it said. Was its voice coming from the back seat or the radio speakers? ‘I will not be buried here again!’

‘But we’re in Ireland,’ Tony pointed out, reasonably, via the rear-view mirror. ‘We’re in Cork?’

In the mirror he saw, next to the head, a gaunt woman he did not know. Or did not know he knew. She was all bone and wrinkle.

‘We are in my crooked eye!’ the head bawled, alone on the back seat. ‘DRIVE ON TA FUCK!’

But Tony didn’t know how to drive. Though he pressed the accelerator with his foot, the car wouldn’t budge. Just revving, just noise.

‘What are these boxes next to me?’ the head brusquely asked. ‘They reek of age.’

Tony looked in the rear-view and saw his vinyl collection, all boxed up, collected first in London – fifty pence a record in the basement of a place in Greenwich – and added to then throughout the years. ‘That’s the collected,’ he told the giant head.

‘THE COLLECTED WHAT?’

‘My records. I collect records. Music?’

‘AH, MUSIC! The music of what happens, that’s what I liked best. When I was… How long til we’re back in Ireland? I fucken CANNOT be buried here again, and will not, and you must get me home.’

‘I can’t impress this upon you enough,’ Tony said, slowly and clearly. ‘We are on the South Ring dual carriageway in Cork. That’s the slip road for Rochestown there.’

‘WE ARE IN MY EYE!’ the giant head bawled.

The gaunt woman grinned at him through the rear-view. ‘Listen to yer man,’ she said. ‘Eyes!’ Every wrinkle was a smile.

‘Do you know how to drive?’ he asked her, and yet he had already released the handbrake and the car began to roll slowly backwards.

‘THIS,’ the head boomed, ‘is not my country. This is an abomination.’

‘You’re not wrong there, Eyes,’ the gaunt woman said.

Hands to the wheel, Tony tried to keep the reversing car on the tarmac and off the grassy verge. Mercifully, there was no other traffic on the road. ‘You might not be wrong there,’ he said, and it was his radio voice that emerged.

‘I asked them to take me with them. Me head. I was a good friend to them. I told them stories of old. I fucking sang to them, Tony. I fucking sang to them.’

‘Right.’ The car rolled backwards. Tony’s whole being felt… braced.

‘Me! A giant! And what’d they do? RATS! Don’t open the door, I said! God knows where they are now.’

They rumbled into the verge and the box of vinyl bounced violently.

‘Sorry about that,’ Tony said. ‘Doing my best here!’

‘Get us home quick, Anthony. Before I’m fucken buried again. EIGHTY JOYOUS YEARS ME HOLE!’

‘Where is home though?’ Tony asked, the radio voice again. Fuck.

‘THE AULD SOD, YOU CRETIN! THE AULD FUCKEN SOD! Come on will you, you ignoramus! You amadán! GET US HOME!’

But no matter how hard Tony tried or how much abuse the giant head hurled at him, or how the gaunt woman smiled, they made no progress. What seemed to be the city of Cork lay in front of them, and the county seemed to lie around them, but they only revved and rolled backwards on the dual carriageway, forever, even after the point in the dream where Tony realised he was dreaming.

[static] and when he did awake, did it not for the briefest moment feel like he’d woken into someone else’s dream? [static]

_________________

OFF-AIR, the night sky was a wide open space, but then the grey morning hauled itself out from underneath the distant edges and the slates of the terrace rooftops began to clarify, one deep dull colour to another. She should really have known more specific names for the colours but she didn’t. The cans she had this night were power orange and shock white, their brightness so far from the colour of that city, the colours of that warm dawn wind moving over cold air.

She made one last mark, the can’s near empty rasp the sign of a decent night’s writing; the blockygood letters of a throwup, big and square and bright. Of course you always got a little more time on these ancient terrace lanes, where the roofs were all different heights, sort of leaning on each other, lanes watched only by cats and puddles and grates and the ghosts of the sewers. Fifteen times tonight she’d made her mark – her name – both large and small, bombs, tags and throw-ups, all around the lanes on the North Mall. Remember me, you smug fucks. You drunken fucks. You rich, moneygrabbing fucks. You snobby fucks, you fucking shits. You fucking shits with your vampire smiles. You remember my name.

A cough, someone coming. In a panic, she thrust the can into her big pocket, as if a guard might come around the corner right then, or some early-morning dog walker or jogger… But there was no one there on the old terrace lane, only herself. Only herself and the wind, and the damp brick walls and curtained windows, and two cats yowling at each other somewhere nearby, and bodies turning in sleep in bedrooms all around her, all around her in a city that sprawled and twitched, mossy rooftops and parked cars and cracked paving slabs and the river that split and diverged along by maltings and walkways, that ran along behind the streets of government departments and hotels and guesthouses and warehouses, the river merging again then and swinging out past the dockyards to lose itself to the harbour. And her mother, her father, her sister, all asleep in one little room in one little guesthouse in that city.

Who had coughed then? Maybe no one.

Maybe God.

But she had given up God after making her confirmation. She’d asked the Holy Spirit to let them keep the house, and to get the leccy back on, but no appearance or help from the Holy Spirit, so fuck God. It is very tricky to explain to your friends why you have no electricity in the house. You can’t say it’s gone all over the estate, because they live on the estate and their leccy is obviously on. Trickier again to say you’re moving house but not say where you’re moving to. You just sort of have to disappear, let them forget you.

No, there was no cough, nobody there; she’d see no one til she got back out onto the Mall, and she went that way now quietly, watching the first gulls come down from over the rooftops and the cranes. She would get back to the guesthouse, slip in, fit into her place. Get a couple of hours’ sleep before she was supposed to go to school. Mam and Dad probably knew she was gone from the room alright. Probably. But they didn’t know her name. Her real name. All over the city – on every wall, lamp post, bin and door…

‘You off to work this early, love?’

It was that skinny alco she always saw dancing outside McDonald’s. He was just sitting up on the riverside bench and looking over the water, the vague, middling tide. He yawned. His shaven head was all scars. Could he see her or was he only talking to someone imagined? ‘Hah? Early to work is it?’

‘Yea.’ She clenched the spray cans in each pocket. Why had she stopped by him?

‘Grand morning for the walk in.’

‘Yea.’

‘I’m an agent of thought you know…’

‘Cool.’

She started to walk on, past him, but then he stood up into her path and raised his arms like wings.

‘I got the milk too! He said to me, he said you better watch it. I said, watch it? You fuckin know me, man!’

‘Yea,’ she said. He was only a couple of inches taller than her, him by the bench, her by the river railing.

‘It’s not fuckin on me,’ he suddenly spat. He was pleading – this man with bony cheeks, and bruises and scabs all over his face – but he seemed not to be seeing her. ‘It’s on him.’

‘Yea,’ she said. ‘I’m off to work now though. See you.’

He turned as she tried to squeeze past, close enough to smell the vomit. ‘Fifteen years he fuckin knows me!’ he cried.

She focused on the space between his arms and the railing – walked straight through it. Left his pleading behind her, hoping he wouldn’t follow. But he wasn’t the worst, only another sad human in a derelict city. She hurried on towards the crossing and the bridge as a silver Mazda charged past, speeding to make it through an orange light, the puddles of yesterday’s rain hissing, and then another car behind it, and suddenly there was the white noise of the morning picking up.

_________________

OFF-AIR, elsewhere, Marta came into the kitchen and went straight to check if the cat was in her bed.

Lou was hunched over a bowl of cereal before heading to the radio station. ‘Still no sign of her.’

‘Still no sign,’ Marta sighed.

‘She’ll come back, love.’ Lou tipped up the remains in the bowl and slurped. ‘If she’s not back by Friday, we’ll put it on the radio.’

_________________

ON-AIR

A VOICE

Who’s there?

————

TONY

Keep your ears peeled for the hourly cash call, coming up in just a few minutes’ time…

————

A VOICE

The point is, right, is that nobody’s thinking of the thousands dying every day in the Middle East. They’re only thinking about their own.Why haven’t we been up in arms for thirty years, for all the deaths in these places with names that are hard to pronounce?

TONY

Well, there’s a thing, Declan, called emotional proximity?

————

A VOICE

Plasma cutters came into contact with some old oil—

————

A VOICE

SWAT teams are currently storming an Anglican church in—

————

A VOICE

Thanking you for two decades of support in our efforts to provide the best deals in home appliances—

————

TONY

And so how exactly are we only ten per cent human?

A VOICE

Well, these microbes that we talked about, Tony, that we often hear about, that live in our body – well, studies have shown that actually they make up a much larger portion of the body than previously thought. In fact, close to ninety per cent of the body is made up of these organisms that do not originate in the body itself. In my book, I explore this very finely poised ecosystem… the ecosystem that each person is—

————

A VOICE

And of course you’re goosed then…

————

A VOICE

It’s the food, Tony. We just don’t know what we’re putting into our bodies anymore.

TONY

And you reckon it’s some secret form of government control?

A VOICE

I do, yea. Whether we know it or not we are controlled by unseen forces, Tony…

TONY

But our bodies?

A VOICE

Sure your body is your mind—

————

A VOICE

The Bishop, we call him, Tony!

————

A VOICE

Fix eight out of ten breakdowns right there on the road—

————

A VOICE

But would these crayturs not have access to bombs of mass destruction? Could they not be blowing us all away right now?

————

A VOICE

See, all we really are, Tony, is transformed groceries—

————

A VOICE

… are living in fear. London is not a place you can go now. Every restaurant, pub, museum is a target. They’re coming for—

————

A VOICE

… an eighty-seventh minute substitute—

————

A VOICE

YOOOOUUUU’RE TALKING TO TONY!

TONY

Is that Eamonn Carter? Eamonn, it’s Tony Cooney here making that hourly cash call…

EAMONN

Oh god, I missed it! Is it thirty-seven, Tony?

TONY

No, Eamonn, unfortunately it was just a little higher; it was fifty-seven—

————

A VOICE

… building traffic along Collins Quay at the moment, starting to look a bit congested on this Friday morning—

————

A VOICE

Unfold yourself—

_________________

BROADCASTING SIMULTANEOUSLY on 5264 kHz + 1420 MHz…

playback:

the pale moon was rising above the green mountain / the sun was declining beneath the blue sea…

first voice:

[static] one… one… seven… eight… [static] two… one… seven… seven… [static]

_________________

OFF-AIR, someone named Ann, dying in a hospital bed.

Would anybody come to her?

What had that man said, something about mothers?

… What?

As she stirred, she again imagined, or perhaps remembered, or had perhaps dreamt saying to Doctor Madden: I have waited my whole adult life to be told by you or someone like you that I had cancer. I knew it would happen. I didn’t know which cancer it would be, or how I’d find it, but I knew this appointment would come, some day, in a room like this. And I knew my eyes would fall upon the posters as you told me, so we wouldn’t need to look at each other. And I knew I would say thank you. Because I would already be seeing the world in a different light.

Or maybe she’d only described it that way to Tony that time? It was hard to remember anything when the brain was so foggy with the chemo and all the rest. You spent a lifetime trying to clarify things and it all went foggy on you anyhow.

In her weakness she could only half turn her head towards that angle of window she had, and she saw now, sort of above her, a cloudbruised sky, and the presence of a sun blanching the roof of the Wilton Shopping Centre. Water boiled somewhere, it sounded like. She coughed a bit, and it hurt in a distant way. Her head was spinning. She was dreaming. A small dog was barking somewhere; voices mumbled away behind curtains: home; a funeral. Or was it all on the radio? A time came to her: walking in rain, with wet socks, and finding a pub with a fireplace. And these chaps there all glued to the Rose of Tralee on the tele behind the bar… What was this taking place in her mind now? Memory? The pain settled into her, away from her somehow, and then there was the hospital ward again. Her in the bed, her arms by her sides again, still dying.

Open the channels.

She looked for a button to press, or a dial to turn.

A VOICE

They are in fact reduced to a set of learned and practised responses to a set of predictable verbal, visual and situational stimuli. They rely on stereotypes, Tony. They’re inflexible—

She found herself able to fiddle with the button to clear slight static, just when Tony Cooney told her that a horse broken loose on the South Ring dual carriageway was causing chaos. A brief bloom of light fell across the little plastic radio; then a cloud, and darkness with it, seemed to fall right into the hospital ward, right over her bed, as a chorus of phone-in voices beheld:

The woes of a landlord at the mercy of vicious tenants…

The release of a rapist back into the same community in which he had offended…

The inflated price of licences for farmers’ market stalls…

And Keary’s Hyundai again offered four-thousand-euro scrappage bonus.

And there had been a decrease in miscarriages.

And the sinking of the Edmund Fitzgerald was remembered nearly fifty years later.

Then it was seven minutes past ten. Phone numbers were repeated, and then a haunted caller phoned in to recount for the show how twenty minutes into the performance of Hamlet at the National Theatre on the South Bank in London, shooters had burst in and started firing in all directions. Some people ran for the exits and some people followed the actors exiting left to backstage, and some people, like this caller, cowered on the floor between seats and played dead, waiting to be shot in the back where they lay. And this caller did not flinch or pause or whimper as she explained that she felt lucky that she’d been there alone, and not with a friend or a partner or a family member – that she hadn’t had to lie next to her dead boyfriend, or mother, while she pretended to be dead herself. She described the silence of the fallen audience as the gunmen walked about the theatre, checking for survivors with their guns raised, and she explained that she could see only dust rising into the spotlights, and could hear only the crying out in pain or pleading of the ones hurt but not dead. And, after a few minutes then, the gentle murmur of many phones vibrating. And the caller said that this murmur increased into a chorus, and that she realised then, or after maybe, that already word must have been spreading to news outlets and social media, and that all the murmuring, the vibrating of phones in dead or dying people’s pockets was their loved ones checking if they were okay. Well, she told Tony Cooney, they were not okay. And she was lying there all this time – who knew who else was still alive and doing the same as her – and hearing now even the odd ringtone of a phone someone had forgotten to switch to silent mode, and the odd burst of gunfire. She was lying there next to a dead person and she didn’t know whether they were male or female or whatever else, because at first she’d tried to run, and she’d left her seat and ended up in another row, and the whole time she said she was just trying to breathe as quietly as possible and not move, and was waiting for something to happen – she didn’t know what – and then she heard a very loud and sudden bang and things landed on her – bits of wood and dust and ragged wet material that might have been cloth or might have been… well, skin – and yet still she just lay there, in dread of being seen moving, and then moments later there was another explosion – and then

HELEN

… absolute chaos like, Tony – and that must have been when the SWAT teams arrived and, and, and…

[static] there was then at least two full seconds of dead air, as much as you can realistically allow, timed to perfection by TONY COONEY, a DJ with thirty-five years broadcasting under his belt [static]

TONY

In my thirty-eight years[lies!]as a journalist, Helen, that is the most horrific thing I have ever heard. I don’t even know what to say to you, Helen. I’m sitting here with tears streaming down my face. I’m stunned. Lou is stunned in the producer’s booth. We’re all stunned—

[static] i have my doubts about whether there were tears streaming down TONY’s face. but maybe you’d believe it. maybe it’s true [static]

Helen agreed with Tony, though Tony hadn’t necessarily said anything to agree with. Helen, who was from Buttevant but had been living in London twenty-two years, had never lost her accent, and her voice didn’t waver; she finished the story with the matter-of-factness and defiance of someone who’d been ripped off by a car salesman. She insisted that unlike many others she wouldn’t come home – that would be letting them win – and she said that she would never wash the clothes she had worn that night. Filthy though they were, she never wanted to forget just how close she’d come to death, and just how costly freedom in the West really was…

But then, after a few ads and jingles, they were back to rent control, and tried to decide – with callers for both sides – who was more put out, landlords or tenants. Some texts came in chastising Tony for being too harsh on an elderly caller, which texts, in fairness to him, he read out on air. The word martyrs was thrown around, as was the word allocated. Ann turned painfully and began to drift again. There were a number of firsttime callers moved by Helen’s story and discussion ensued about all the Irish people coming home from London and where they’d go and how they’d fit back in. Rent allowance was nowhere near the rate of the average monthly rent. The rise in homelessness was something per cent in a decade, someone claimed. There was nobody living in the small towns anymore, the people said; they were referred to as ghost towns, as the pain subsided and the hospital tuned out, and Ann tuned into the ward briefly again, before the mind returned, at the very last, to the Rose of Tralee.

_________________

ON-AIR

TONY

So these terrorists are communicating via shortwave radios? Isn’t that a very old-fashioned thing?

A VOICE

It is, Tony. But surprisingly successful. Militaries have been doing this since World War One, like. Basically, you only need a very cheap shortwave radio to tune into these frequencies from anywhere in the world.

TONY

It might be worth explaining – because this is fascinating to me – how shortwave radios actually work.

A VOICE

Well, Tony, radio is the broadcasting of radio waves out into the world. Radio waves are just another frequency on the electromagnetic spectrum, like microwaves or even visible light. And basically the shortwave radio signal is a sine-wave that undulates like the surface of an ocean, and can travel vast distances to broadcast… well, whatever you want… Because when you direct them at the ionosphere—

TONY

What’s the ionosphere when it’s at home?

A VOICE

Basically it’s the outermost layer of the earth’s atmosphere, and you can bounce these shortwave signals off of it, so that they deflect back to Earth great distances away. It’s called tropospheric ducting, which is basically bouncing the signal up to the ionosphere and back to Earth over and over until the signal is gone over the horizon. FM can’t do that, but AM can you see.

TONY

Right.

A VOICE

So hence, back in World War One, spies were given number code books, and then in order to communicate with each other, the military and their spies could use shortwave to broadcast and receive these sequences of numbers, which, when checked in the code books, could be deciphered as messages. So you could be in Russia, for example, and tune into a broadcast and hear a sequence of numbers, and those numbers were a message for you, or you could relay information back to base if you had the ability to broadcast your own sequences of numbers…

TONY

Which was why they were called numbers stations.

A VOICE

Exactly, Tony.

TONY

And so the evil, evil people running a guerrilla war in London now are using these very old methods to organise and carry out attacks.

A VOICE

Exactly, Tony. But it’s not new in today’s terms either. I mean Cuban drug dealers have been using shortwave for years. See everything on the internet now is traceable, crackable, recorded, whether you’re browsing incognito or not. And I suppose the levels of encryption and internet decoding now just aren’t as secure as good oldfashioned—

————

TONY

Irish people are coming home in their droves – Cork people are coming home in their droves – but they’re not all finding places to live and work. The government are thrashing out the final details of repatriation and relocation grants, as well as emergency housing—

PAT

But why can’t we open our doors to these people, Tony?

[static] northside accent, always the kindest [static]

I mean, Tony, loads of us have spare rooms nowadays; anyone with kids gone to college or whatever. Why can’t we throw open the doors to these people who need us. I for one have two beds in the spare room. The twins are gone off to college in Waterford. Any man or woman home From London is welcome to them. Pass on my details, Tony. Do what you like. They’re our own people, Tony. And they’re leaving their jobs and their homes out of fear. They’re essentially refugees, Tony!

TONY

They are, Pat. They are. You’re not wrong. If only there were more like—

————

MARIAN

And why… these displaced persons you’re talking about, Tony. How are they different from the migrants who’ve been flooding into Europe from war-torn countries for decades? What’s different that we’re suddenly offering up the kids’ bedrooms to them? Because they’re Irish, is it? Because they’re puuuare Cark? Shouldn’t we be stuffing them into Direct Provision like so many poor creatures before them? Or are they exempt from that because of the colour of their skin? Should we be giving them an allowance of nineteen euro a week?

TONY

Well there’s a thing, Marian – I’ve said it before – it’s called emotional proximity, and it explains why we care more about people dying in London or, say, during 9/11, or the Paris attacks, than – rightly or wrongly – people dying in the Middle East, or coming over from distant lands…

MARIAN

Distant lands? Arra come on now, Tony, don’t be codding yourself—

————

TONY

… and how long are you seeing him, Daniela?

DANIELA

Nine months, Tony. It’s been a great nine months too!

TONY

And ye met online?

DANIELA

We did. I wouldn’t normally do that kind of thing. I—

TONY

But you think nine months is too soon to move in together?

DANIELA

Well, I dunno. It’s a bit soon like, isn’t it?

TONY

You know, Daniela, it’s funny, I’m squeezing my brain back through the years and I do believe that the Dancing Queen and I moved in together after nine or ten months together. I had to snag her good and early you see – no one else would put up with me! But… d’you know, seriously, I think sometimes you just know. You don’t know in the sense of the Hollywood movies – love at first sight and all that blather – but you know that you trust someone enough to open yourself up to them. And once you’ve opened yourself up to them, and they to you, then everything after that is easier. Even the hardest stuff. I’ve talked on here before about losing our son after only a few days… But yes, once you open yourself up there are less games, less problems… And it’s easier to compromise. There’s that saying about one person wearing the pants or whatever, well that’s a wet auld rag too if you ask me. The best relationships, the ones that last, are the ones that involve compromise. Where you wear the pants in certain things and she wears the pants in other things. Be they logistical things or emotional things. The Dancing Queen, for example, she’s a bit more thrifty than me and so she handles the bills, the internet providers, that kind of thing. But I’m the man that knows which bins go out on which nights… And it goes further than that. You trust the other person to look after you. You trust them to lead the way when you can’t, or to ease off when things are a bit manic. You trust them to remain open with you. You put yourself on the line and they put themselves on the line – through grief and through joy… It’s all an ongoing… fluid compromise; it’s not a fixed contract or a game like the glossy magazines would have you believe. So, Daniela, what I’m saying… I think… is that if nine months feels right, then maybe it’s right? And if you’re not ready, you’re not ready, you know?

DANIELA

I suppose so.

TONY

God, I remember the early days, meeting the Dancing Queen to go to the cinema, or dancing or what have you. I wasn’t too long back from London that time. I remember the talking. A lot of talking. Good talks, good times. But they’re still good and all. The talking never stops. Never let the talking stop. Never bottle up something – just blast it out because if you can’t say it to your number one, who can you say it to? And never go to bed mad at each other either. I’ll give you that one for free. Sure, there’ll be fights – arguments and what have you; god knows myself and herself have had our fair share of roaring matches – but talk it out before you go to sleep and if you never go to bed angry you’ll be fine. I’m not gonna count up the years now because she’ll have my guts for garters for outing her, but I will say that I put it all down to compromise and talk and not going to bed angry, and Lou is glaring at me here to stop pontificating and reminiscing and get on with the show and sher look, Daniela—

————

TONY

… the washing machine changed more lives than the internet has—

SUSAN

Now, I wouldn’t know about that, Tony, because he does the clothes and I do the dishes. The utility room is his sanctuary as he calls it. But it’s as if motherhood has been turned into a problem. Since when did that happen?

TONY

As the previous caller said, we need to get over ourselves.

_________________

BROADCASTING SIMULTANEOUSLY on 5264 kHz + 1420 MHz…