Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Lightning

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

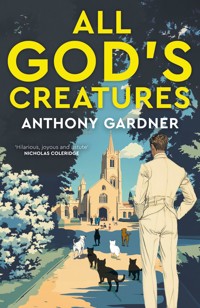

'Hilarious, joyous and astute' – Nicholas Coleridge Mild-mannered editor Ben Fairweather is horrified when his genteel religious magazine is taken over by a fanatical movement which holds that animals are closer than humans to God and should receive Holy Communion. Amid a national religious revival, this belief becomes mainstream and Ben is cancelled as a petphobic bigot. He finds a new job as a pianist in a nightclub. There he meets Anita Scott, a journalist bent on exposing the Russian oligarch Oleg Ogorodnikov – newly elevated to the House of Lords – whom she accuses of cultural vandalism. The scheming Ogorodnikov is actually involved in something far more sinister: a plot to take over London's financial system. Little realising that his fingerprints are all over the theological unrest too, Ben and Anita are drawn into a world of spies, art forgery, AI and murder, with their own lives on the line. Anthony Gardner's ingenious caper combines madcap excitement with a deftly satirical portrayal of the crazy beliefs, chaos-spreading Russians and rise of the robots which seem to define our age.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 272

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2025

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Published in 2025

by Lightning

Imprint of Eye Books Ltd

29A Barrow Street

Much Wenlock

Shropshire

TF13 6EN

www.eye-books.com

ISBN: 9781785634406

Copyright © Anthony Gardner 2025

Cover design by Ifan Bates

The moral right of the author has been asserted. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Our authorised representative in the EU for product safety is:

Logos Europe, 9 rue Nicolas Poussin, 17000, La Rochelle, France

For Anthony, Finn and Sasha

Contents

Prologue

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Acknowledgements

Also from Lightning

PROLOGUE

It was past midnight when the Archbishop of Canterbury climbed into bed. His wife was already half asleep, rolled up in more than her fair share of the duvet.

‘How did the installation go?’ she murmured.

‘It was very moving. I think our new bishop will do very well. But there was…an incident.’

‘What sort of incident?’

‘Those wretched protesters again. One of them brought a miniature Schnauzer. It bit the choirmaster halfway through the Gloria. There was even some kind of monkey – on a leash, thank goodness.’

‘You must crack down on them.’

‘That’s easier said than done, darling. What do you suggest?’

There was no reply. A light snoring filled the room.

Ill at ease, the Archbishop tugged the duvet towards him and fell into a fitful sleep.

CHAPTER 1

i

Eastern Europe’s most feared spymaster was struggling with his budget.

‘How can the Paris assassination possibly have cost that much?’ he demanded peevishly. ‘I could have done it myself for half the price – first-class travel and a weekend with the wife at the Ritz included.’

‘There were the bodyguards to be disposed of too, General. And the investigating magistrate to be squared.’

‘Even so. These “miscellaneous expenses” – that’ll be booze and call girls, if I know Grigorski. Where is he, by the way?’

‘Just back from Turkmenistan, General. He’s been overseeing the forged currency operation there.’

‘Tell him I want to see him.’

The aide withdrew.

The General fingered the paperweight in front of him. A souvenir of the Sochi Winter Olympics, it took the form of a globe with a skier who became engulfed in snowflakes when you shook it – ironic, he thought, given the amount of snow they’d had to import to make the games possible. Grigorski had been there too, in charge of hacking the phones of visiting dignitaries. The man was a pain in the neck, with deplorable personal habits, but he was undeniably versatile and efficient.

The General’s eyes returned reluctantly to his spreadsheet. All those millions of roubles gone on electronic equipment and IT! In his days in the field, he had been as keen on new technology as the next man, but now it was out of control, like a monstrous fledgling constantly demanding to be fed. Yes, there was fun to be had in shutting down a city’s power grid or paralysing a country’s health service – but it didn’t compare with the good old days of cloak and dagger. How he missed the dead-letter drops and the nights with binoculars by the Berlin Wall!

The aide returned. ‘Major Grigorski, sir.’

Grigorski looked even rougher than usual, with two days’ growth of stubble covering his thick jowls. His broken nose was red with sunburn, while the scar that bisected his bald patch – a memento of hand-to-hand fighting in Chechnya – was preternaturally livid. His breath had heavy hints of caried teeth and unassimilated alcohol.

‘Sit down, Major. How was Turkmenistan?’

Grigorski settled his bulk uneasily into the chair, as if a stranger to furniture.

‘Everything went according to plan, sir. Five hundred thousand forged notes in circulation, and a false trail leading to two top treasury officials.’

‘No bodies at the bottom of the Atrek?’

‘Not required this time, sir.’

‘Just as well, I suppose. But always good to keep your hand in.’

‘Yes, sir.’

‘The old ways are best, eh?’

‘No doubt about that, sir.’

‘So.’ The General picked up the paperweight again, turning it thoughtfully in his hands. A blizzard descended obligingly on the plastic figurine. ‘I’m sending you to London.’

‘London, sir? But I thought Crimea – that unfinished business…’

Grigorski’s disappointment was understandable. Crimea had been his finest hour, directing Russian special forces masquerading as a local militia. Smoke and mirrors did not get any smokier.

‘It can be finished later.’

‘But the airliner we shot down,’ he continued. ‘If it comes out that the orders were issued by—’

‘It won’t.’

Grigorski nodded. He was a man who picked his fights carefully. There was no point in antagonising the General.

‘What does the London job involve, sir?’

The General watched the last snowflakes settle. ‘Gaining control of the British financial system to disrupt what is left of democracy there. Also laundering five billion dollars for the Party Chairman. And you can start by growing a proper beard.’

ii

The death of Ben Fairweather’s dog was what set the whole business in motion.

To his mind Molly, his golden retriever, was an animal without peer. Beautiful, loyal and good-tempered, she loved Ben wholeheartedly, as he loved her: throughout his twenties, she offered him the companionship that womankind had so far failed to provide. To walk with her at dawn along a riverbank rich with darting birds and rising mists was, he felt, to know the joy of the world as God first created it.

Then, at ten, she was diagnosed with bone cancer. Her decline was swift and shocking: even the prime cuts of beef that Ben fed her by hand barely aroused her interest. The vet recommended putting her down.

For a week, Ben carried her into his office in Oxford’s Jericho district and watched her slumbering uneasily in her basket. Editing the magazine his great-grandfather had founded seemed of trifling importance beside the fate of his beloved pet. When at last he rang the vet’s surgery to make the necessary appointment, it felt like the most appalling decision of his life. Kings of old, he reflected, had had the power of life and death over their subjects. He could think of nothing worse.

The day came all too quickly. ‘It’s all right,’ the sympathetic nurse lied to the stricken animal as the fatal injection was prepared. Afterwards, Ben found his way uncertainly out into the daylight, dazed and heartbroken.

‘You should write something about her,’ said Tamsin, his editorial assistant, as Ben stared at the photograph on his desk. ‘Write something about Molly.’

‘What, in Cathedral?’

‘Yes. Something about a pet’s place in creation. How they bring out the best in us. Whether we will meet them again in heaven.’

Two years out of university, Tamsin was the most recent recruit to Cathedral’s threadbare staff. A large, confident young woman whose colourful hair accessories would have held their own on a Christmas tree, she showed every sign of going far in journalism – if the profession survived another decade.

There had been a time when the post of editorial assistant on Cathedral had been much sought-after. Cadwallader Fairweather had gambled boldly in launching an ecumenical Christian magazine in the 1940s; but the scope of its features was broad, and the quality of its arts pages second to none, and before long it was spoken of in the same breath as Horizon and The Spectator. Graham Greene and Tom Wolfe had graced its summer parties; Norman Mailer was said to have snogged Simone de Beauvoir at one of them; Dylan Thomas and Aldous Huxley had almost come to blows at another. But by the time Ben and his brother Sam inherited it, the magazine had suffered two decades of decline. Selling the offices in Fleet Street and moving to Oxford had kept the creditors at bay, until an expensive website which produced less revenue than the old ads for clerical clothing plunged Cathedral back into the red.

The brothers had little in common. Ben, at 30, was a tall, dark-haired figure whose gaunt good looks and thoughtful demeanour brought to mind a Left Bank intellectual in 1960s Paris; Sam, two years his junior, was a podgy, ebullient redhead who hurtled through life like a bowling ball in search of a skittle.

‘We should kill the print edition,’ said Sam. ‘Print is dead.’

But Ben was a traditionalist who thought it bad for humanity to spend every waking hour staring at screens.

‘Over my dead body,’ he said.

So Sam resigned (‘I’m getting out while the going’s good’) and took a job in Australia.

Then, almost overnight, came the Great Awakening. Hundreds of thousands turned to God as a refuge from climate change, disease and hate-fuelled politics. Church congregations grew spectacularly; Ben thought Cathedral’s circulation would too. Instead, like playground bullies, the big media companies moved in, luring away his best contributors. Now he and Tamsin were writing half the magazine between them under a variety of pseudonyms.

‘Would it be one for Cecil de Vere or Thomasina Campion?’ he asked. ‘I see them both as animal-lovers.’

‘Write it as yourself,’ said Tamsin. ‘Make it the lead feature. It’s a gift for the cover.’

Ben realised that she was right. He gazed again at Molly’s photograph, searching her great, soulful eyes for inspiration. Then he began to tap at his keyboard.

iii

Ben was pleased with his article. It began with a tribute to Molly and a moving account of the gap she had left in his life, before addressing the theological issues. Christ had spoken only of salvation for humans; Descartes had insisted that animals had no souls. Yet Isaiah promised a heaven where the wolf would dwell with the lamb – and the Pope had spoken of a ‘paradise open to all of God’s creatures’. C.S. Lewis, irritatingly, had hedged his bets. But, Ben asked in conclusion, ‘Can we conceive of a God who blesses us with the love of animals, only to separate us from them for eternity?’

He was even more pleased with the cover, which showed two golden retrievers leading the animals into Noah’s ark.

Still, no one at Cathedral was remotely prepared for the response the article brought.

‘We’ve had more than two hundred emails over the weekend,’ said Tamsin. ‘I think we should give the entire letters page over to them.’

More was to come. Traffic on the expensive website reached an all-time high. Ben’s piece was chosen by a popular digest for its ‘Best of British articles’ page; the Press Association syndicated it. Ben was interviewed on Radio 4, and filmed for the local TV news walking the riverbank he had trodden with Molly.

He was not altogether happy with the attention: he wondered whether he was exploiting Molly’s memory for the sake of increasing circulation. But, he told himself, even this moment in the spotlight was unlikely to change Cathedral’s fortunes. If the magazine he loved was to vanish from the newsstands, it might as well be remembered for its celebration of his beloved dog.

iv

Two weeks later Ben was invited to lunch at the at the Ashmolean Museum’s rooftop restaurant. The email came from the Kentucky office of Dr Alex Rosewater, who professed admiration for Cathedral and wondered whether he might be of some assistance to it.

‘Just been looking at that Uccello battle scene downstairs,’ he said as they shook hands. ‘Isn’t it something? What magnificent horses – but how they must have suffered! It doesn’t bear thinking about.’

His accent had the merest hint of a southern drawl. He was a short man with a round, youthful face and black side-parted hair, dressed in a blazer, striped tie, chinos and highly polished shoes, so that – though probably in his fifties – he gave the impression of a well-turned-out schoolboy. A small enamel badge on his lapel bore a picture of a white cat and the letters AGC.

‘This is very kind of you, Dr Rosewater,’ Ben said when they had ordered.

‘I’d be glad if you called me Alex – everyone does. May I take the liberty of calling you Ben?’

‘Certainly.’

‘I like your magazine, Ben; I like it a lot. A publication that speaks to different denominations at this time of disunity – it’s a fine thing. And the history! All those distinguished contributors over the years – you must be proud to have inherited such a great tradition.’

‘I’m very lucky.’

‘Not in my opinion. You’ve more than earned your place at the table. That article about the animal soul – it was a fine piece of work: well-argued, wide-ranging and profoundly moving. I’m not ashamed to say that I wept tears for your Molly.’

‘Thank you.’

‘Now, I expect you’re wondering about this.’ He tapped his lapel badge.

‘A little. AGC stands for?’

‘All God’s Creatures. We’ve been operating for two years now in the US. We believe that theologians have paid too little attention to the role of animals in Our Lord’s plan, and we want to set that right. An article like yours is very much a step in the right direction.

‘To cut to the chase: we have some very generous donors, and some of their contributions have been earmarked for establishing a media presence. I hope you’ll forgive me, Ben, if I mention that I know a little bit about Cathedral’s finances. They’re not in great shape. That’s no reflection on your editorship: it’s the way things are with most magazines. I have faith in you, Ben, and I believe that, with a cash injection, Cathedral could really go places.

‘In short, rather than throw all these funds into social media, we would like to make a sizeable investment in Cathedral. We would, of course, need some shares to show for it, but you and your brother would keep a controlling stake. I’m not suggesting for a moment that All God’s Creatures would interfere with editorial matters: all we ask is you keep the animal-soul debate alive. And judging from the letters you’ve had over the past fortnight, that shouldn’t be too hard.

‘To put an actual figure on it…’

He wrote a number on the back of a business card and pushed it across the table. Ben’s eyes widened.

‘You look happy,’ said Tamsin when he got back to the office. ‘Have you got an idea for the leader?’

‘Yes,’ said Ben. ‘I rather think I have. It’s going to be about guardian angels.’

CHAPTER 2

i

There was a broad smile on Oleg Ogorodnikov’s face as he wriggled into his peer’s robes. In two weeks he would be introduced to the House of Lords, and he was confident of looking the part. He regretted, however, that he was not allowed a fur trim from his own sable farm: how tiresome these British were about their little regulations! After all the money he had given the party of government, they could surely have bent the rules for him.

‘Very good,’ he declared in a voice which, despite valiant attempts to anglicise it, carried a deep imprint of his upbringing among Moscow’s criminal underclass half a century earlier.

A phone rang.

‘It’s Downing Street,’ said his PA. ‘The Prime Minister would like to speak to you.’

Hm, thought Ogorodnikov: perhaps something could be done after all.

‘Oleg!’ The voice at the other end was as ingratiating as ever. ‘Are you well?’

‘Thank you, Prime Minister. Just one thing: for the House of Lords – this ermine…’

‘Sorry, Oleg, it’s not a great line. But yes, you’re right – vermin everywhere. Can’t be helped, I’m afraid. We spend a fortune on rat-catchers, but these old buildings… Anyway, I just wanted to give you a heads-up: the Ogorodnikov Tower is not going to get the go-ahead. Too high for the London skyline. The planning people won’t allow it. Sorry, but it can’t be helped.’

‘The planning people!’ Ogorodnikov was apoplectic. ‘But you are the Prime Minister. Overrule the planning people!’

‘I would if I could, but it’s enshrined in law.’

‘Then change the law!’

‘We’re doing our best. But these things take time.’

‘Then I’ll just have to relocate my company and build the tower somewhere else. Abu Dhabi, Singapore…’

‘Be reasonable, Oleg.’

But ‘reasonable’ was a foreign concept to Ogorodnikov. He rang off and threw the phone back to his PA.

Too high for the London skyline! For years, governments of every hue had rubber-stamped any new skyscraper that came along; size and architectural merit had been irrelevant. Why should that stop now?

There must be an enemy at work – some rival oligarch, jealous of his success. He, Oleg, would winkle him out and eliminate him.

He could, of course, fulfil his threat and relocate. How the Prime Minister would miss his largesse! But there would be few opportunities to wear his robes in Abu Dhabi.

‘The priest is here, your lordship,’ said his PA.

‘Send him up.’

The figure who emerged from the lift wore a black cassock with a heavy chain and crucifix across his chest. A black hat was perched on his head, and a thick black beard hid most of his face. Ogorodnikov stared, then burst out laughing.

‘Major Grigorski!’ he exclaimed. ‘Welcome to London!’

ii

Not since his first days as editor, four years before, had Ben climbed the stairs to Cathedral’s offices with such a spring in his step. Alex Rosewater’s investment, he told his friends, had ushered in a new era for the magazine. Contributors who had jumped ship were returning, bruised from their experiences in the bear pit of mass media and happy to accept a generous increase in their retainers. An energetic young woman from All God’s Creatures had revamped the website and taken control of the social media feeds. Advertising revenue was up, even if some of it came from strange sources, such as an animal mortuary in Oregon. Ben was able to give Tamsin her first-ever pay rise.

It was with alacrity, then, that he accepted Alex Rosewater’s invitation to a second lunch.

‘Looking forward to it, Ben,’ said Rosewater. ‘There’s someone I’d like for you to meet.’

The someone was a blue-eyed, flaxen-haired woman a few years younger than Ben. So beautiful was she that, had she possessed the merest trace of warmth or humour, he might have fallen in love with her there and then. Instead he felt like an ill-starred Pygmalion, faced with a sculpture that refused to come to life.

‘This is Dr Pamela Pettifer,’ said Rosewater, pouring him a glass of champagne. ‘We are celebrating Pammy’s new appointment as lecturer in animal theology.’

Ben tried to imagine himself addressing the ice maiden as Pammy. He couldn’t.

‘Animal theology,’ he said. ‘That’s a new one on me. What is it?’

‘It is about to become the fastest-growing field of graduate study in the US,’ said Rosewater. ‘A proper definition of the Almighty’s relationship with the animal kingdom is long overdue. I’m proud to say that All God’s Creatures has this year endowed thirteen chairs at carefully selected American universities. We are now looking to Pammy to spread the word in Europe, starting with her fellow Brits.’

‘Wow,’ said Ben. ‘Congratulations, Dr Pettifer. Can I ask you what led you along this path?’

‘I have a bachelor’s degree in sociology, a masters in marketing, and a doctorate in psychology. My thesis was on the dreams of cats. When I met Alex, this seemed like the obvious next step.’

‘So you haven’t actually read theology?’

‘I believe in coming to things with a fresh mind. We don’t want to take on board the prejudices of the past.’

‘And where is your department?’

‘At the University of Rickmansworth. I have just accepted my thirtieth graduate student.’

Ben was astonished. How had thirty people signed up at an obscure university to study a subject he had never heard of, taught by a woman who hadn’t studied it herself?

‘Now, as I told you, Ben, I’m a hands-off investor,’ said Rosewater. ‘I have no intention of telling you how to edit your magazine. But Pammy has some very interesting ideas for articles, and though the big media honchos would kill for them, I’ve asked her to give Cathedral first refusal. That OK by you?’

Ben didn’t feel he could say no.

‘Fantastic,’ said Rosewood. ‘Let’s drink to that.’

iii

Two weeks later, an article by Pamela Pettifer arrived in Ben’s inbox. ‘Time to embrace instinctivism’ ran the heading.

‘The Book of Genesis tells us that animals were created before man and woman,’ it began. ‘It is therefore clear that they have a more important role in God’s plan.’

Ben read on with growing incredulity.

‘On a societal level, and in the context of the space I occupy, I am a human being. But that does not mean that I should identify as one. Not the least of Darwin’s errors was to claim that our species had evolved to be superior to others. The truth is that the further we have embraced the heresy of evolution, the further we have departed from God’s template.’

There was more – much more – in the same vein. ‘It is time for us to dispense with the old histories, geographies and hierarchies,’ the article concluded, ‘and partner with animals to curate a supportive and systemic empowerment principle. Those of us with agency must prioritise actions to deliver sector-by-sector change, call out faulty mechanisms and achieve instinctivism with measurable outcomes. Until then, we are barking in the dark.’

‘Barking indeed,’ thought Ben.

He showed the article to Sister Theodosia, the elderly Nigerian nun who edited the books pages.

‘As I recall,’ she said, ‘there was a seventeenth-century heresy along these lines, inspired by Jan Swammerdam’s Ephemeri Vita. Several of its members were burnt at the stake.’

‘I don’t think that’s something we can really do with Dr Pettifer.’

‘Are you sure Dr Pettifer actually exists? This reads as if it had been written by a lemur with a laptop.’

‘I’ve met her. If she is a lemur, she was very well disguised.’

‘This term ‘instinctivism’ is particularly puzzling. What do you think it means?’

‘No idea. Tamsin, do you know?’

‘Haven’t the foggiest.’

Ben sat down and wrote a rejection which seemed to him a masterpiece of tact. A few minutes later his phone rang.

‘You’re rejecting my article. Can you explain exactly why?’

Dr Pettifer’s voice was like a tray of ice cubes being poured into a deep carafe.

‘Well…you never explain the title, for one thing.’

‘Please don’t tell me you’re not familiar with instinctivism. There are more academic papers being written on it right now than on any other subject.’

‘Humour me.’

Dr Pettifer sighed. ‘The greatest weakness of the human race is its tendency to rationalise. Animals, on the other hand, rely on instinct, which means that they are closer to their Maker. If we are to aspire to the same state of godliness, we must stop privileging the rational and recognise the superiority of instinct.’

Ben was so astonished that he struggled to respond. ‘I see… But since the Bible says that humans were created after animals as the summit of God’s creation, I don’t think your theory holds water.’

‘The Bible was written by those who can write.’

‘So you’re rejecting its authority, and saying that animals are superior to humans because they’re less intelligent.’

‘If you want to put it crudely, yes. That is now the accepted view.’

Ben had had enough. ‘Not at Cathedral it isn’t. My rejection stands.’

He ended the call. The next day Alex Rosewater rang.

‘Pammy tells me you turned down her article, Ben. I’m very disappointed.’

‘If you’d read it, Alex, I think you’d understand my position.’

‘I have read it. Pammy runs everything past me.’

‘Then you’ll know that it’s (a) incredibly badly written and (b) nonsense.’

‘I have to question your editorial judgement, Ben.’

‘Then we must agree to differ. Goodbye, Alex. I’m sure Pamela will find another home for her piece: one of the big media honchos is bound to snap it up.’

iv

The Cathedral AGM took place the following month. Ben, Alex Rosewater, the company secretary and Mrs Prynne, a nervous-looking octogenarian who had inherited a twenty -five percent shareholding from her uncle, were the only people in attendance.

‘That brings us to the end of the agenda,’ said Ben at last. ‘Any other business?’

‘Yes,’ said Alex Rosewater. ‘I propose the motion that Ben Fairweather is no longer competent to edit the magazine and should be replaced forthwith.’

Ben laughed. ‘This is ridiculous,’ he said.

‘Does anyone second this motion?’ asked the company secretary.

Mrs Prynne glanced at Rosewater and put up a shaking hand. ‘I do,’ she said in a small voice.

‘I don’t know why you’re wasting your time,’ said Ben. ‘The two of you hold forty percent of the voting shares between you. I and my brother, whose proxy I am, hold sixty percent. Motion rejected.’

‘Sorry, Ben,’ said Rosewater, ‘but I acquired your brother’s shares yesterday. Perhaps he didn’t have a chance to tell you. You’re out.’

v

Ben walked home in a daze. That Sam had stabbed him in the back was not particularly surprising: the two of them had never got on. But how could his brother have betrayed the magazine their forebears had built – the magazine their father had entrusted to them?

Ben considered his own position. He had no aspirations to wealth or fame; all he had ever wanted was to earn a modest living doing his best by an institution he revered and loved. Now it had been snatched away from him when he least expected it. This, he imagined, was how Adam and Eve had felt when cast out of Eden; what Lucifer had suffered when thrown down from heaven to the infernal realm.

Over the following weeks, Tamsin acted as his eyes and ears in the Cathedral offices. The first development was the appointment of Pamela Pettifer as editor – or, as she preferred to be called, Chief Word Organising Officer, a term much mocked by columnists sympathetic to her predecessor.

‘She hasn’t a clue,’ Tamsin reported. ‘She didn’t know what a copy date was, or a flat plan. It’s like putting a Punch-and-Judy man in charge of an ocean liner. Theodosia’s been told she can’t review any books that don’t relate to animals, and the TV highlights are entirely devoted to pet-rescue programmes.’

Pamela’s first issue was ridiculed by the media commentators. The cover was a nativity scene in which all the humans except the infant Jesus were blanked out and the sheep and oxen were given haloes. ‘Animal crackers,’ read the headline in one newspaper. ‘Away in a manger, or away with the fairies?’ read another. And yet, Tamsin told Ben, Cathedral’s social media following had quadrupled in the space of a week.

Ben couldn’t bear to look at the magazine.

‘Try and put it behind you,’ he told himself. ‘See this as an exciting new phase in your career.’ But finding a niche outside Cathedral was harder than he expected. He had made the mistake of immersing himself entirely in an editor’s duties, rather than using his position to raise his own profile; consequently, his name meant little to the big media honchos. The depth of his knowledge and excellence of his prose seemed irrelevant.

In despair, he turned to teaching.

CHAPTER 3

i

A recurring nightmare haunted Kevin Murphy. It took him back to North London on the night of the shooting.

He hadn’t been in the gang for long. Jez, the weirdo he’d met in the young offenders’ institution, had lured him into it – or maybe, as Kevin preferred to think, taken pity on him. Either way, it seemed like the only avenue open to him. He had no family: hadn’t since his parents’ death in a car crash when he was six. None of the foster families he’d been through would want to see him now – certainly not with a conviction for receiving stolen goods (even if, as his lawyer had argued, he was too naïve to realise they were stolen). That left the room in a hostel that the social worker had found for him; but he’d had enough of rules and of the people who ran those kind of places – this one a prize nonce, by the look of him.

So when Jez said they could both kip at his, and added that he’d take Kevin to meet Big Mario and the Dapper Danz, it seemed a no-brainer.

What set the Dapper Danz apart was their appearance. Their territory was only a modest slice of Islington, but there wasn’t a better turned-out gang in London. Every Saturday they could be found at Bernie’s Cuts, the barber shop run by Mario’s cousin, whose skill with a pair of clippers was second to none: there their undercuts and taper fades were fine-tuned and their beards teased and trimmed to perfection. Their clothes were freshly laundered and immaculate, except when business got lively. As Mario used to say, ‘I don’t want to see no stains on your clobber, only the other f—er’s blood.’

Kevin had only ever worn what he’d been given: he could measure out his life in hand-me-down T-shirts and scuffed trainers. But to shop – or more often shop-lift – with the Dapper Danz was to enter a new world. To wear something no one else had ever worn; to open a box and rip aside the tissue paper and just smell the cleanness of a new pair of shoes – that was a sensation that thrilled him.

The Dapper Danz didn’t need to steal: they made plenty of money from their drug-dealing. It went against the grain, however, to pay for something that could be had for nothing; and if they got caught…but they never got caught. Big Mario had them too well trained for that.

His qualifying adjective was well deserved. He stood six foot five in his Nike Air Vapormax trainers, and weighed eighteen stone before lunch. His hands were like baseball gloves; his collar size was the largest in the Fred Perry catalogue. His mighty frame was sustained by a diet of takeaways from the local branch of North Dakota Fried Chicken and Jewish puddings cooked by his girlfriend Sharon’s mum: chocolate and pecan tarheel pie was a particular favourite, backed up by the stash of Sephardic meringues he kept in the side pocket of his blue Porsche Macan. With family, though, he stuck to pasta and vitello tonnato, and considered it a point of honour to take a third helping.

‘You know about Alcatraz, right?’ he said. ‘The cooks made some of the tastiest food in America. Why? Because the governor clocked that most riots started because of bad food. He reckoned that if he kept the prisoners well fed, he wouldn’t get no aggravation. And he was right: one ex-con said he used to dream of the spaghetti Bolognese. Well, that was my mum’s attitude too: give the boys a good puttanesca and they’ll behave. Which we do – with her, anyway.’ And he gave a chuckle from deep within his diaphragm.

You could hear Mario coming by the music from his Porsche’s sound system. Not for him the dark, monotonous grime favoured by his rivals: the rhythms and melodies of Eurodisco were what floated his boat. Baccara’s Yes Sir, I Can Boogie was testing the speakers when he picked Kevin up in Liverpool Road that evening.

‘Got some business to attend to, Kev,’ he said. ‘Reckon you could be useful. All part of your apprenticeship.’

Kevin climbed into the back beside Jez. Mario’s brother Gino occupied the front passenger seat.