11,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Atlantic Books

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

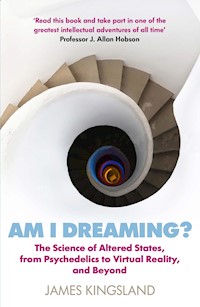

When a computer goes wrong, we are told to turn it off and on again. In Am I Dreaming?, science journalist James Kingsland reveals how the human brain is remarkably similar. By rebooting our hard-wired patterns of thinking - through so-called 'altered states of consciousness' - we can gain new perspectives into ourselves and the world around us. From shamans in Peru to tech workers in Silicon Valley, Kingsland provides a fascinating tour through lucid dreams, mindfulness, hypnotic trances, virtual reality and drug-induced hallucinations. An eye-opening insight into perception and consciousness, this is also a provocative argument for how altered states can significantly boost our mental health.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2019

Ähnliche

Am I Dreaming?

JAMES KINGSLAND is a science journalist with more than twenty-five years’ experience working for publications including New Scientist and Nature. Most recently he was a commissioning editor and science production editor for the Guardian. He is the author of Siddhartha’s Brain: Unlocking the Ancient Science of Enlightenment.

Published in hardback and trade paperback in Great Britain in 2019 by

Atlantic Books, an imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd.

Copyright © James Kingsland, 2019

The moral right of James Kingsland to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

Every effort has been made to trace or contact all copyright holders. The publishers will be pleased to make good any omissions or rectify any mistakes brought to their attention at the earliest opportunity.

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Hardback ISBN: 978 1 78649 550 1

Trade paperback ISBN: 978 1 78649 551 8

E-book ISBN: 978 1 78649 552 5

Printed in Great Britain

Atlantic Books

An imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd

Ormond House

26–27 Boswell Street

London

WC1N 3JZ

www.atlantic-books.co.uk

For our guardian angels,Stefana, Biz, Amit and Brooks

Contents

Introduction

1. Magical Thinking

2. Dream On

3. Holidays from Reality

4. Puppets on a String

5. Wonder Child

6. Mother Ayahuasca

7. Death of the Ego

8. The Wonderful Lightness of Being

9. The Void Between Dreams

Epilogue

Sources

Acknowledgements

Index

Introduction

Is all that we see or seem, but a dream within a dream?

Edgar Allan Poe, ‘A Dream Within a Dream’

The shaman’s assistant shone her torch in my face and whispered in my ear, ‘Are you OK, James?’ like a kindly nurse to a patient coming round after an operation. A French woman in her early thirties who spoke several languages fluently, her role in the ceremony was to translate the shaman’s Spanish instructions, issue calm reassurance as required and usher us to the toilets in the dark. I told her I felt just fine. ‘That’s good,’ she said. ‘Do you want to drink again?’

The ink-black interior of the ceremonial hut, or maloca, raised on stilts over a muddy stream in the Peruvian Amazon did feel like a hospital ward. My fellow patients were sitting or lying on wipe-down plastic mattresses in the darkness on either side of me, each with a puke bucket within easy reach. The more organized among us had brought our own torches to light our way on the almost inevitable, urgent dashes to relieve ourselves that we were going to have to make during the night.

A whole range of afflictions had brought us to this jungle ward in February 2017. Some were seeking healing for drug addiction, depression or past traumas. Others, like me, simply yearned for a greater sense of meaning and purpose in their lives, a spiritual epiphany that mainstream religion had somehow failed to deliver, an antidote for the frustration and cynicism of middle age. For weeks, in preparation for the ‘operation’, we had abstained from sexual activity and followed a highly restrictive diet free from red meat, spices, salt and pepper, oils, animal fat, dairy, chocolate, carbonated drinks, tea, coffee and alcohol. At dusk, the female shaman had ritually cleansed us with wild tobacco smoke, blowing it onto the palms of our hands, the tops of our heads and into our clothes. Finally we were called forward one at a time to gulp down a personalized dose of the bitter medicine, known as ayahuasca or yagé. Once swallowed, there was no turning back. We were strapped in for what could be a frightening ride.

‘Are you sure about this?!’ had been the response of my former colleague Ian Sample, the science editor at the Guardian newspaper in London, when I emailed him a month earlier to tell him what I was planning. ‘It sounds fun/terrifying/bonkers.’ I was sure – at least at first.

Before the arrival of European settlers and Christianity in the late fifteenth century, ayahuasca was widely employed by the indigenous peoples of the Amazon in their religious ceremonies, in rites of passage and as a medicine. During the colonial era its use was suppressed and survived only in the relatively inaccessible Upper Amazon, but in the past decade plane-loads of Western tourists have descended on the region to drink the psychedelic brew, and in parallel there has been an explosion of scientific interest.

I travelled to Peru partly as research for a Guardian article but also in the hope of improving my own well-being. A few months before my adventure, I read a study suggesting that ayahuasca can change a person’s outlook, making them less judgemental and emotionally reactive, improving their ability to stay mindful in challenging circumstances.1 A few studies hinted that the hallucinogenic tea might also have antidepressant properties. Others suggested it could be used in conjunction with psychotherapy to treat addictions and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).2,3 To be honest, this all seemed a little too good to be true. I had interviewed some of the scientists behind the studies and now I wanted to try the medicine for myself.

After filling out a battery of medical questionnaires in which I painted a rosy picture of my physical and mental health, I was excited to be offered a place on an ayahuasca retreat at the highly-regarded Temple of the Way of Light near Iquitos in Peru. The temple’s intensive treatment programme would involve five ayahuasca ceremonies in the space of nine days, personal consultations with facilitators, workshops and cleansing ‘flower baths’. Reassuringly, the ceremonies would be conducted by experienced Shipibo healers with English-speaking facilitators on hand throughout.

A little over a week before my flight, however, I started to get cold feet. It wasn’t the rare but widely reported fatalities among the thousands of Western tourists who had drunk ayahuasca in South America over the past few years that spooked me. (On closer inspection most, if not all, of these deaths turned out to be associated with poorly run retreat centres and caused by factors unrelated to ayahuasca itself, such as reactions to other psychoactive drugs and a road traffic accident.)4 It was my family history of bipolar disorder.

I don’t personally have the condition, which causes alternating bouts of crushing depression and mania verging on psychosis, but drinking ayahuasca or smoking its psychedelic component dimethyltryptamine (DMT) has been known to ‘unmask’ these symptoms in people who are genetically predisposed to develop either bipolar disorder or schizophrenia.5 The same is true of all the classic psychedelics. When the psychedelic properties of DMT’s hell-raising cousin lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD) were first identified in the forties, scientists were initially more intrigued by its ability to provoke symptoms of psychosis, such as hallucinations and delusions, than they were by its promise as a medicine. In a series of clandestine research projects in the US in the fifties and sixties as part of its MKUltra programme, the CIA investigated the possibility of using LSD as a mind-control weapon to temporarily scramble the brains of high-ranking enemy officials before important meetings or speeches, as a form of mental torture to elicit confessions from foreign agents, and to brainwash subjects into becoming ‘robot agents’. The investigations were eventually abandoned after it became clear the effects of the drug were too unpredictable, but not before hundreds of unwitting subjects had been dosed without their consent.

LSD, DMT and psilocybin (the psychedelic component of magic mushrooms and truffles) are grouped under the title ‘classic psychedelics’ because they all achieve their transient, psychosis-like effects by binding to the same molecule in the brain, the serotonin 2A receptor. The receptor’s normal binding fellow – serotonin – is a neurotransmitter that boosts nerve signal transmission, and there has been speculation that the receptor is involved in responses to extreme stress. Worryingly, some antipsychotic drugs appear to work by preventing serotonin from binding to the serotonin 2A receptor. In the days and weeks after the immediate effects of a classic psychedelic have worn off, the risk of psychosis or mania is very small, even among those like me who may be genetically vulnerable to these conditions. Nevertheless it has been estimated that around a third of the people who are unlucky enough to be affected in this way will go on to develop schizophrenia or bipolar disorder.6 This was starting to scare me. Was I really prepared to gamble with one of my most precious possessions – sound mental health – for the sake of curiosity?

Foolishly, I deliberately hadn’t mentioned my bipolar family history in the screening questionnaires for the Temple of the Way of Light. I had also failed to reveal an odd experience at university decades earlier when I felt wired for several days and nights for no apparent reason. Was that a manic episode, I wondered, a glimpse of a genetic chink in my mental armour? A dose of Valium prescribed by my GP at the time brought me safely back down to earth, so I hadn’t thought much more about it. The experience never recurred, but the recollection was making me feel increasingly jittery about drinking ayahuasca.

When I did finally come clean about my family’s history of bipolar disorder, the Temple of the Way of Light promptly withdrew my place on its programme. Mental breakdowns after ceremonies are rare, wrote the bookings officer in a friendly but firm email, ‘but we have seen how difficult it can be to recover from psychosis for some of these folks, and we are very aware that we are not equipped with the professional psychological staff to safely support these individuals’. The nearest general medical clinic, she wrote, let alone a hospital, could only be reached by a two-hour hike through the jungle and a boat trip down the Amazon. My request to attend the ceremonies as an observer was also turned down, on the grounds that my presence might disrupt the shamans’ delicate healing work with participants.

But my flight to Iquitos was already booked and I was determined to at least witness a ceremony at one of the other centres in and around the city. If the experience was sufficiently reassuring, I decided, I would screw up my courage and drink ayahuasca myself, on the condition that I received a relatively low dose and didn’t have to commit to a mentally gruelling series of ceremonies. After three or four failed enquiries and just days before my flight, I found a reputable retreat centre about twenty miles from Iquitos that was prepared to accept me on these terms.

The Dios Ayahuasca Sanaciones healing centre turned out to be little more than a cluster of thatched huts in a clearing about half an hour’s hike through the jungle from the highway. There was no electricity or running water, but the place was clean and well-maintained. The staff, though they spoke little English, were helpful and my fellow guests were friendly, relaxed and welcoming. My confidence was growing. Through the translator, I spoke to the shaman who runs the centre about my family’s history of bipolar and asked if he thought it was a good idea to drink a small dose of the medicine at that evening’s ceremony. Gazing at me intently for a few seconds as if he could read the stability of my mind in my eyes, he nodded and said yes, everything was going to be fine. So it was that eight days after being turned away from the Temple of the Way of Light, I found myself sitting on a mattress with my back to a wooden pillar in the centre’s maloca, waiting for my first psychedelic trip to begin. I knew a little about the biochemistry of what was now happening inside my body. The genius of ayahuasca is that, in addition to DMT from the shrub Psychotria viridis, the brew contains chemicals from the vine Banisteriopsis caapi known as ‘monoamine oxidase inhibitors’, which disarm an enzyme that would otherwise break down the psychedelic before it could have any effect on the nervous system.

About half an hour after ingesting the foul-tasting liquid, I convinced myself I could feel the drug’s hot, unstoppable progress through my body, from my guts into my veins and onwards to my brain, then spreading like a fire beneath my scalp. A burning drop of sweat ran down my brow and into one eye. As DMT took control of my senses, the nocturnal chorus of hoots, barks and growls in the surrounding jungle seemed to grow louder, answering the shaman’s melancholic, enchanting icaros or medicine songs, which are said to summon the plant spirits. Directly behind me, close to the pillar where I sat, I distinctly heard the rhythmic clatter of a chakapa, a rattle made from a bundle of dried palm leaves. But when I turned my head there was nobody there. Regardless of the evidence of my eyes, however, the rattling continued.

My neighbour a few feet to my left, a man in his early twenties from Macedonia and a veteran of half a dozen ceremonies, reached for his bucket, dry-retched into it and giggled happily. I was beginning to feel a little nauseous myself, though I failed to see the funny side. Apart from vomiting and diarrhoea – which afflict nearly everyone – ayahuasca rookies are often gripped early on in their trip by overwhelming terror. Having your ego chemically stripped away can feel like the annihilation of death. ‘Surrender yourself to the experience,’ I’d been advised a few weeks earlier by an experienced user. If you don’t fight the drug, sensations of extraordinary bliss and peace may follow; vivid visions of exotic rainforest creatures, healing encounters with the plant spirit Mother Ayahuasca, mind-blowing adventures.

Waiting for the ceremony to start about an hour earlier, my other neighbour – a Londoner in his thirties – had reminisced about a trip the previous year during which he roared into the night sky over the jungle in the cockpit of a space shuttle. Looking down at the ceremony in the rapidly receding maloca far below, he saw pyramids erupt through gaps between the floorboards. My own visions, after a more modest dose of the medicine, were rather less dramatic. When I closed my eyes I found myself on a balcony in a colonial-style monastery overlooking a cloistered courtyard awash with seething, brightly coloured geometric shapes. But what filled me with joy and wonder – the thing that really sticks in my memory – was the shaman’s plaintive song; its volume, beauty and ineffable meaningfulness magnified by ayahuasca.

Some time later – I thought it must be nearly dawn but it turned out only a few hours had passed – and the effects were starting to wear off. There had been no terror, no ego dissolution, only an awestruck fascination with the whole perception-warping, magical experience. I was nauseous and my gut was rumbling but I hadn’t felt the need to use my bucket or dash to the toilet since downing the brew. So when the shaman’s assistant approached to ask me if I wanted to drink again, I was tempted. Then I remembered the small but real risks for people like me with a family history of bipolar disorder or schizophrenia and decided that enough was enough for now. I didn’t want to push my luck and so I declined. Almost immediately I regretted not diving deeper into the extraordinary realms of consciousness I had heard others describe. I was left with a nagging sense that my life would have been richer for the experience. In the years following this first, tentative experience I have embarked on bolder adventures, with happy results, some of which are described later in this book.

To ingest a psychedelic drug is to take a leap of faith. Nobody can tell you in advance what will happen in that strange inner world after everyday reality has been suspended, or what the enduring consequences might be. Put like this it sounds frightening, and yet we make a similar leap into the unknown every time we close our eyes to sleep. Who knows what nightmares may come? There are other similarities. Like tripping with your eyes tightly closed, dreams are almost completely isolated from external, sensory reality and are mostly visual. The ‘hypnagogic’ visions of random, abstract shapes that people sometimes report seeing as they fall asleep recall the geometric patterns often witnessed during a trip. In both dreaming and tripping, time perception is distorted and, like those that happen during a trip, the bizarre narratives and encounters of our dreams are almost always first-person, subjective experiences – quite unlike watching a film or TV drama. Could the same underlying mechanism explain the biological purpose of dreams and the therapeutic promise of psychedelics?

Sigmund Freud, the father of psychoanalysis, argued that dreaming provides a safe outlet for fulfilling repressed sexual desires, and that by interpreting dreams a skilled therapist could bring these desires to light and effect a cure. Rather than uncovering repressed urges, neuroscientists now believe it is the occasionally unnerving suspension of sensory reality checks that occurs during all altered states – from dreams and hypnosis to psychedelics and deep meditation – that unlocks their potential benefits. In the process, however, they reveal a truth about ordinary consciousness every bit as unsettling.

Altered states of consciousness are temporary deviations from our normal, ‘baseline’ waking state involving multiple changes in perception, cognition, emotion and arousal levels. They may occur spontaneously, for example as a result of trauma, an epileptic fit or near-death experience, or they can be deliberately induced by drugs or practices such as sensory deprivation, fasting, breathing techniques or focused awareness. Regardless of their cause, by loosening the normal sensory and cognitive restraints, altered states can result in a breakdown of long-established beliefs about what is likely or unlikely, probable or improbable. They can even dissolve the deeply entrenched distinction between ‘self’ and everything else.

Dreams are the archetypal, everyday altered state that everyone has experienced, but what exactly are they for? Before you were born, dreams set the stage for your entrance into the world. If your mother was given an ultrasound scan at thirty weeks’ gestation, it would have revealed your almost continuous rapid eye movements, or REMs, characteristic of dreaming sleep. What you dreamed in the warm darkness of the womb is anyone’s guess, but your brain was almost certainly teaching itself two vital skills. First, as you kicked out and clenched your fists (unlike later in childhood and adulthood, your muscles still worked in your dreams), you were learning what it is to be an active agent situated in a physical body, known as ‘core selfhood’; and second, as your eyes darted about behind closed eyelids – as if following the action in some hidden drama – you were taking your first lessons in how to see.

Once veiled in superstition, we now know that dreams play a crucial role in wiring highly adaptable brains, not only in humans but also in most other mammals and young birds. This is probably why human foetuses, infants and children dream so much. In adults, dreams are not only important for consolidating the memories needed to perform unfamiliar, complex tasks for the first time, but also for emotion regulation and creativity, as we shall see.

That dreams are a virtual-reality training ground for waking activities may not come as a surprise, but what if I were to tell you that even as you sit reading this, everything you see, hear, taste, smell, feel and touch is also only virtually real? The words on the page, the feel of the book or e-reader in your hands, perhaps the sound of distant traffic or conversations, the sense of your body occupying a particular space in a particular posture – none of these experiences arises directly from the data gathered by the photo-receptors in your eyes, the touch receptors in your fingertips, the microscopic hairs in your inner ears and the ‘proprioceptors’ recording the position and movement of your muscles. The weight of evidence now suggests they are virtual realities conjured by the brain using the same neural machinery that it uses to make your dreams.7 According to this unnerving new perspective, rather than passively building a faithful, inner representation of the external world, the brain is constantly trying to stay one step ahead of the game, drawing on its past experiences to predict what’s happening. Sensory information is not disregarded, but is relegated to the role of reality-testing the brain’s guesswork and, as we shall see, it isn’t necessarily given much credence.

The virtual nature of perception helps to explain the host of self-deceptions, sensory illusions and hallucinations to which we are prey. Why else would these distortions of reality, like dreams, seem so perfectly convincing? Having painstakingly scanned our own brains, recorded their electrical activity and scrutinized their constituent nerve cells, humans face a realization almost as disorienting as that faced by Keanu Reeves’s character, Neo, in The Matrix as he watches a spoon held in a girl’s fingers wilt before his eyes – then spring back upright. This is no cheap magic trick pulled off using subterfuge and phoney cutlery. To perform it, Neo is told, you must only realize the truth. ‘There is no spoon,’ the girl explains. ‘It is not the spoon that bends, but only yourself.’8

Like Neo, it’s time we came to terms with the discovery that the mind plays a leading role in everything we feel, see, hear, smell, taste and touch. This isn’t to say that there is no objective, external reality, but our conscious representations of it are the product of the brain’s innate virtual-reality generator. Neuroscientists now believe that in visual perception, for example, what we see is not the result of a three-dimensional, internal representation that our sensory cortex has laboriously built from the bottom up, step by step, by detecting features such as edges, lines and blobs in the raw sensory data, but effectively the idea of a spoon – the concept of a spoon that encompasses everything we know and have ever experienced in the world of spoons. We begin assembling our perceptual concepts from scratch in the womb and in infancy, collecting multisensory associations and committing them to memory. As a baby being weaned off milk and building a concept of spoons, among other things you learned to associate these objects’ visual characteristics with those of food and your parents, with how the objects felt in your mouth, the taste of the food and the sensation of hunger satisfied. But the more you learned the less you relied upon raw, sensory spoon data and the more your consciousness drew upon the internal, virtual spoon.

As the brain develops, perceptions start to look less like direct sensations and more like predictions informed by context and similar past experiences, like templates held up before the mind’s eye in order to judge how well they match information streaming from the senses. The job of the brain, it seems, is to minimize any discrepancies or ‘prediction errors’ by selecting the template that is the best match, perhaps updating it to further reduce future mismatches.

Needless to say, all this happens unconsciously and at lightning speed, but if we could run through the process in slow motion it might look something like this. Imagine you hear a knock on your front door. You open it and see – what? Your brain uses the context (time of day, whether you’re expecting someone to drop by, and so on) to bring up the most probable templates: the postman, a friend, a neighbour, a complete stranger. The template it settles on will be the one that minimizes prediction errors, the differences between each available template and the limited sensory data on offer. It’s the postman! Even so, a glaring visual-error signal remains. He has grown a beard, so your brain updates its ‘postman’ template accordingly.

This usually works perfectly well: not only does it save a lot of time and processing power, it also resolves the tricky problem that sensory information is inherently sparse, fuzzy and unreliable. We can never know what’s happening in the world directly; we only infer it from context and the available sense data. Just as you draw upon your past experience to judge the veracity of the stories when you browse a news website (because journalists can’t always be relied upon to report the news accurately and impartially), the brain must arbitrate between what it has learned previously – what it thinks it knows – and fresh sources of information. Instead of placing all its trust in meagre, noisy data, consciousness is founded upon prediction and expectation. The downside is that perceptions are easily bent out of shape – much more easily, in fact, than bending a spoon without touching it. As the girl in the film says, ‘That would be impossible.’

Occasionally, when the brain slips up, its perceptual guesswork becomes glaringly apparent. Anyone who has ever stared out of the window of a moving train as the landscape or cityscape races past will be familiar with illusions of movement when the train comes to a halt. I remember my astonishment as a child when I first looked down and saw the ballast streaming alongside the tracks after our train had come to a halt at a station. Of course it was not the stones that were moving but my mind, which had become accustomed to expect this rapid flow. It took twenty seconds or so for the sensory data from my eyes to correct this impression, updating my brain’s predictions about what was really happening.

Most of the time perceptual distortions like this hide in the shadows of ordinary consciousness, but they can be manipulated and enhanced at will. For thousands of years, humans have exploited the virtual nature of perception to transport themselves into alternative realms of experience. Among the powerful tools we have developed to twist our brains’ predictions are hypnotic suggestion; trance states induced by dance, music or drumming; spiritual disciplines such as fasting, isolation, sleep and sensory deprivation, meditation and breath control; and, of course, psychedelic drugs. In thrall to these mind-bending influences, people are easily convinced that a spoon is wilting before their eyes, that black is white, that they are communing with their ancestors, with gods or angels, alien beings or the spirits of plants and animals. They may come to believe they can see into the future and resolve all manner of difficulties. And, perhaps most extraordinarily of all, they may shed their ‘ego’ or sense of autobiographical selfhood and perhaps even their bodily identity, melting distinctions between them and their surroundings, suddenly discovering a sense of union with everyone and everything else in the universe.

We have come to know these vivid, phantasmagoric experiences as altered states of consciousness, but they tell us much more about everyday consciousness than we might care to admit. They are powerful demonstrations of the endlessly creative, virtual nature of everything we have ever thought, felt or perceived.

Altered states are also proving invaluable tools for ‘re-tuning’ the mind, adjusting the relative influence of fresh sensory experiences and established thought patterns and behaviours. They have enormous untapped potential for humanity. As we will see, psychedelics and meditation, in particular, are likely to be game changers in the coming years for people with intractable illnesses characterized by inflexible, destructive mental states, such as treatment-resistant depression, PTSD and addiction.

Around a decade ago, like so many others entering the middle years of their life, I began to ask myself: Is this it? On the surface I had little to complain about. I was happily married, living in a spacious house with a garden in a London suburb. I had a solid career in science journalism behind me and stretching ahead over the twenty-five or so years remaining before I could pay off my mortgage and retire. At forty-two years of age, I was earning a decent wage plugging away at a computer keyboard on the science desk of the internationally-renowned Guardian newspaper. I had climbed as high as I was likely to get on the journalistic career ladder, having started out in my twenties as a sub-editor on freebie magazines and newspapers for medical professionals, followed by a ten-year stint in my thirties as a sub-editor, editor and later writer for New Scientist magazine. With many of my youthful ambitions and passions satisfied, comfortably adapted to the ecological niche I had made my home, all that remained was to live out my life as a finished, fixed ‘me’. This was not a prospect I relished, however. I did not like being me very much.

To give you a flavour of the person I was becoming, every weekday morning I would pedal to work on my bicycle, a journey of about five miles from Kilburn in north London to the Guardian offices in King’s Cross, arriving forty minutes later in a mood fit to kill someone. During the ride everything and everyone would become steadily more hateful. It didn’t help that I was usually running late, so every minor delay, from traffic lights turning red to buses stopping in front of me to pick up passengers, wound my mental springs a little tighter. The breaking point often came on Abbey Road in St John’s Wood at the zebra crossing made famous by the Beatles, where every morning dozens of foreign tourists lined the pavement waiting their turn to be photographed, frozen in mid-stride like their heroes, oblivious to the blaring horns of the waiting rush-hour traffic. I remember one day I was so riled by this selfish behaviour that I didn’t stop, shooting straight over the crossing ringing my bell furiously, barely missing a startled young man.

It was incidents like this that finally drew my attention to the person I was turning into. Rather than growing in wisdom with the passing years, I seemed to be getting angrier and more cynical, and while my political leanings were supposedly as liberal as they had been in my twenties, I realized that, deep down, I was becoming much less tolerant of others’ behaviour and beliefs, who they were and where they came from. I also lacked any clear idea of what I wanted to do with the rest of my life. It was around this time that a Buddhist friend gave me a copy of Mindfulness in Plain English by the Sri Lankan monk Henepola Gunaratana. Maybe my friend had spotted those angry red flags? The book was my introduction to the Eastern idea that, through training, the mind can be persuaded to run along happier, calmer, more compassionate tracks, not simply loaded up with more and more information, which for a long time has been the Western way of thinking. At first I was sceptical, but I later discovered there was a growing body of scientific evidence suggesting that practices as simple as focusing on the breath or repeating a mantra have measurable physiological effects and lead to clear-cut changes in the brain, for example in areas involved in attention and emotion regulation.

I began to work in earnest on changing my mind, meditating first thing every morning and trying to be more mindfully aware from moment to moment of my surroundings and emotional state, not least on my journey to and from work. I was becoming calmer, but I also noticed more subtle effects on my sense of selfhood. I started to question my personal perspective on the world. On rainy days when I took the train rather than cycling, in the midst of the tide of humanity flowing out of King’s Cross station my mind boggled at the sheer multiplicity of these other conscious ‘selves’, each implicitly assuming him or herself to be at the centre of the universe. They couldn’t all be, could they?

Eventually I plucked up the courage to pack in my safe job at the Guardian in order to write Siddhartha’s Brain, a book about Buddhism and the neuroscience of meditation. A few years later, my interest in psychedelic drugs was sparked when I read research suggesting that, after the acute, hallucinogenic effects of drinking ayahuasca have worn off, mindfulness is temporarily boosted to levels usually only seen in people who have been doggedly practising meditation for seven years or so.9 I was intrigued. Given the chance, who in middle age wouldn’t want to become a little less judgemental and emotionally reactive, to roll back some of the stultifying effects of the passing years? Mindfulness already figured large in my life. Could drinking an infusion brewed from the leaves of the shrub P. viridis and the mashed-up stem of the vine B. caapi really offer a shortcut to ‘enlightenment’ that didn’t involve setting aside time every day to sit motionless on a cushion, year in and year out? I began to interview scientists who were researching psychedelics and other altered states, and my personal explorations eventually led to the ceremonial hut in the Peruvian jungle where I drank ayahuasca, and several months later to a darkened hotel room in Amsterdam where I ate psilocybin-containing ‘magic truffles’ for the first time. None of this prepared me, however, for the shock of ego death I experienced one hot afternoon in the Netherlands in May 2018, which I describe in Chapter 7.

Within these pages I explore a new scientific understanding of consciousness developed over the past decade – a grand unified theory that explains how human thought, emotion, perception and behaviour emerge from our brains’ perpetual search for certainty in an uncertain world. In humans this search is also a quest for meaning. As I hope this book will demonstrate, wisely used, altered states are fabulous tools for widening the scope of our quest, restoring the broad, healthy perspective that mental illness, addiction and the passing years can take away. Like a zoom lens, they reveal the bigger picture that we so easily lose sight of the more closely our minds focus on the minutiae of everyday life. They can expand our consciousness to include everyone and everything.

By their very nature, however, altered states are risky. To adjust our focus, they temporarily suspend our sensory and cognitive reality-checking faculties, an issue I confront in Chapter 1. Paradoxically, one of the potential benefits of expeditions into altered states of consciousness may be the fine-tuning of these very faculties, helping us to become more mindful or lucid, even in our dreams (Chapter 2). In Chapter 3, I sing the praises of escapism through virtual-reality technology and video gaming which, contrary to tabloid wisdom, may offer considerable benefits for mental health. Virtual reality and games are also helping to reveal how the brain creates the boundaries of bodily selfhood. In Chapter 4, Balinese dancers and revellers demonstrate how extraordinarily easy it is to slip the anchors of selfhood through trance or hypnosis, allowing humans to assume the identities of gods, farm animals… and kitchenware.

A book about altered states of consciousness would be incomplete without a nod to the genius of Albert Hofmann, the creator of LSD, who from the start recognized the chemical’s promise, not only in psychotherapy but also as a key for unlocking the secrets of consciousness. Fifty years after scientific work on LSD and the other classic psychedelics was effectively banned in the seventies, we are witnessing a renaissance in psychedelic research that has yielded the unexpected insight that the brain is exquisitely poised between order and chaos, stability and flexibility (Chapter 5). There may be even bigger surprises to come, not least if a controversial claim from an Australian PhD candidate – that a particular blend of ayahuasca tea, drunk under strictly controlled conditions, can lift the suicidal depression of bipolar disorder – is proved correct (Chapter 6).

One thing is certain. No matter how spectacular or awe-inspiring our experiences during altered states of consciousness, the insights gained must somehow be integrated into our everyday lives (Chapter 8). Maintaining a daily meditation practice may be particularly effective in this regard, though few people will become as skilled at observing their own mind as Tibetan monks, who can maintain conscious awareness even during non-REM, dreamless sleep, which they use as a training ground for their transition from this life to the next (Chapter 9).

In addition to exploring the rapidly developing neuroscience of consciousness, my hope is that this book will also provide inspiration for readers who want to dip their own toes in altered states with a view to widening the scope of their consciousness – not necessarily through drugs but perhaps through less daunting, gentler techniques such as lucid dreaming and self-hypnosis. Self-hypnosis is a proven technique for overcoming anxieties about situations such as dates, public speaking and job interviews; and lucid dreaming, as well as being great fun, can help see off our nightmares. You’ll find step-by-step guides on how to attain each of these states on pages 57 and 110, respectively.

Over the years, like most humans, I have tinkered with my consciousness in countless ways. I have lost myself in books and music. As a teenager I loved playing the fantasy role-play game Dungeons & Dragons and, as an adult, I have dabbled in the virtual-reality World of Warcraft. I have been hypnotized in the hope that it would erase my lifelong fear of flying. I have meditated, taken all manner of prescription and non-prescription drugs, and trained myself to dream lucidly. None of these experiences fully prepared me for the lurch in consciousness wrought by a high dose of psychedelic that sunny afternoon in the Netherlands. More than any other altered state, these extraordinary drugs lay bare a mind in which our thoughts, beliefs, ideas and expectations play the starring roles in perception and selfhood.

1

Magical Thinking

It seems that as humans, even when all our immediate biological needs have been met, there remains a hunger for meaning. We long for a greater sense of connectedness with nature and the universe, some kind of reassurance that each of us plays a part in a grand narrative that will continue long after we have left the stage. Throughout recorded history, altered states of consciousness – whether they are brought on by drugs, music, drumming, dance, or exacting spiritual disciplines such as meditation, isolation and fasting – have satisfied this profound hunger, a yearning that has nothing to do with the basic biological drives for food, shelter, social status or sex. What other animal seeks out meaning?

This search for meaning is not an idle pursuit. To discover that you play a minor role in a cosmic drama that transcends your everyday self can be hugely beneficial for mental well-being. The impressive clinical effects of psychedelics recorded in studies over the past few years appear to be directly related to their ability to provoke meaningful, even spiritual experiences. The self-transcendent insights they afford have proved particularly helpful for people forced to confront their own mortality. A few years ago, when Stephen Ross and his colleagues at New York University School of Medicine gave a single dose of psilocybin (found in magic mushrooms and truffles) to twenty-nine people struggling to cope with a cancer diagnosis, the psychedelic significantly improved their quality of life and brought immediate and substantial relief from symptoms of anxiety and depression.

Their study employed a ‘crossover’ design: patients either took psilocybin in a first session followed by a placebo seven weeks later, or vice versa. Each was also given conventional psychotherapy. Six-and-a-half months after the treatment, between 60 and 80 per cent were still reporting clinically significant improvements in symptoms of anxiety and depression compared with the start of the trial. Crucially, this therapeutic effect seemed to be mediated by the spiritual insights they had while on psilocybin. Some 70 per cent of all the patients reported that, even though their trip was emotionally challenging, they rated it as among the top five most personally meaningful experiences of their entire lives.1

One of the patients, a fifty-one-year-old woman called Erin, who had been knocked sideways by the news she only had a 50:50 chance of being alive in five years’ time as a result of ovarian cancer, described a vision that gave her a vital insight.2 Under the influence of psilocybin, she saw a round dinner table:

… and at the table was cancer, but it was supposed to be at the table. It isn’t this bad, separate thing; it’s something that’s part of everything, and that everything is part of everything. And that’s really beautiful. It was just a sort of acceptance of the human experience because it’s all supposed to be this way.

She realized that cancer and death must have a place at the table: they are as integral to the natural order as life itself. And with that realization came the peace of acceptance.

Similarly, in a trial led by Robin Carhart-Harris at Imperial College London, reported in The Lancet Psychiatry in 2016, twelve patients with treatment-resistant major depression experienced significant, sustained reductions in their symptoms after taking just two doses of psilocybin one week apart alongside conventional psychotherapy. Again, these clinical improvements correlated with ratings of how insightful or mystical they judged the drug experience to be.3–5

In the modern world, doctors have assumed the healing role once played by priests and shamans, but theirs is a mostly biological conception of illness that can overlook patients’ spiritual needs. Their pills are not designed to restore a sense of meaning, connectedness or purpose to people’s lives. Prozac and Valium don’t work by offering insights into one’s problems but by damping down their emotional impact, which goes a long way towards explaining why conventional antidepressants and anti-anxiety drugs like these must be taken continually for their effects to be sustained, whereas research to date suggests that just one or two doses of a psychedelic can be life-changing. Also worth bearing in mind is the fact that taking conventional antidepressant and anti-anxiety drugs is often associated with side effects such as drowsiness and sexual dysfunction, and can lead to dependence: when patients stop taking them there may be unpleasant withdrawal effects, including a sharp rebound in their original symptoms.

Age-old techniques for provoking altered states of consciousness, such as meditation, sleep deprivation, trance and hallucinogens, are well known for their ability to precipitate spiritual and emotional breakthroughs but, as I would be the first to acknowledge, they are inherently risky for some people. There is a delicate balance to be struck between laying oneself wide open to spiritually meaningful experiences and triggering a ‘psychotic episode’ in which one can lose touch with reality for days, weeks or longer, with hallucinations and possibly delusions of persecution or grandeur. Research suggests that consciousness-warping chemicals and practices allow us to dissolve rigid patterns of thought and behaviour, including drug addiction and depression, like shrugging off old clothes that have grown worn and uncomfortably tight over the years. In the process, however, they expose the naked psyche to the cold blast of painful memories and emotions. And there can be no guarantee that the new clothes the mind finds to put on will fit any better than the old ones. For a few unlucky people, in particular those vulnerable to psychosis, the fit may be more uncomfortable.

All the altered states of consciousness I explore within these pages involve what psychologists call ‘dissociation’ – a temporary disconnection from everyday reality. But for the small percentage of people who have experienced psychosis or who have a family history of bipolar disorder or schizophrenia, these states run the risk of severing this link for longer periods, perhaps permanently. Psychedelic researchers recruiting volunteers for their studies will reject applicants if they fall into these categories, as will many meditation and ayahuasca retreat centres, as I learned to my disappointment. For everyone else, a supportive environment – a calm, protected space with compassionate, experienced individuals on hand – is essential to maximize the benefits and minimize the risks associated with these extraordinary experiences, in particular allowing any difficult emotions and memories that come up to be processed safely. Just as importantly, the healing process doesn’t end when people return to ordinary consciousness. In the weeks and months that follow, the profound insights and revelations must somehow be integrated into everyday life, for example through a daily meditation practice, spending more time in nature, creative pursuits or voluntary work.

If you are wary of the idea of temporarily disengaging from reality, it’s worth remembering that this is what happens every night while you sleep. In the next chapter, I explore the idea that dreaming sleep streamlines our models of the waking world, pruning redundant synapses that have accumulated during the day’s learning experiences and helping our brains to function more efficiently. In order to do this, they must switch off almost all sensory inputs and motor outputs and suspend the mind’s reality-checking faculties.

No wonder dreams, like the delusions of psychosis, are so very convincing. But if this nocturnal housework isn’t carried out properly every night, the nervous system becomes increasingly cluttered with unnecessary connections. Like an ageing desktop computer, this means it works less efficiently, disrupting not just cognition but also homeostasis – the maintenance of a stable internal environment including essential tasks such as regulating temperature, pH and blood sugar levels. Not getting enough sleep (at least seven hours a night) is strongly associated with an increased risk of poor mental and physical health, including depression, suicidal thoughts, cancer, diabetes, heart disease and Alzheimer’s.6,7

The effects of sleep deprivation on homeostasis are particularly striking. While research ethics committees would not allow such an experiment to be performed on humans, rats deprived of sleep for more than eleven days die as a result of a complete breakdown in their ability to maintain a stable body temperature.8

One of the take-home messages of this book is that you can’t reap the restorative benefits of sleep, or any other altered state of consciousness, without temporarily disconnecting from the reality checks that your senses and rational mind normally provide. According to the leading theory of how we develop and maintain our cognitive models of the world, known as ‘prediction error processing’, the streamlining that underpins the restorative powers of altered states can only occur after entire levels of the brain’s processing hierarchy have been taken offline.

The trouble starts when people mistake what they dreamed, or the visions they saw, for reality. Psychiatrists call this ‘magical thinking’. Like many people, I have come to believe that science is our best friend for judging what is and is not real, so I get uncomfortable when some folk who have experienced altered states talk earnestly about supernatural phenomena such as astral projection – the ability to shed one’s physical body and wander the cosmos – past lives and spirit guides. Like the contents of a dream in the moments after awakening, these things can seem all too real. Not even scientists are immune to magical thinking. Shortly before I travelled to Peru, I interviewed a highly respected researcher who has investigated the potential clinical benefits of drinking ayahuasca and personally taken part in many ceremonies. The changes in his worldview apparently wrought by the medicine were startling:

Everything has consciousness. Plants, animals, rocks, you name it. The issue is how compatible is their awareness with our awareness. And in the case of plants they don’t think. Their awareness is very, very different from ours. But when we reach out to the plant world and acknowledge that they feel, that they have awareness, plants will create a kind of hybrid awareness. These are the divas that folks in the shamanic realm will talk about.

Ayahuasca has created a bridge to us, and this bridge is the spirit you will encounter in your ceremony. She is an absolute hard ally in this process. She will help you. If you develop a relationship with her and trust her she will take you exactly where she understands you need to go to heal, and that will be totally different from where your mind will think to go.

This well-meaning scientist’s words only served to heighten my reservations about drinking ayahuasca. His conception of the medicine as opening up a channel of communication with plant spirit guides is in accord with what the shamans will tell you, and is a useful metaphor for how the healing works, but many regular users come to believe in a literal Mother Ayahuasca. Who knows? There may be something to their insight of a hidden realm of plant and animal spirits willing and able to help out with our problems. Personally I prefer to remain sceptical about such things.