6,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Corvus

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

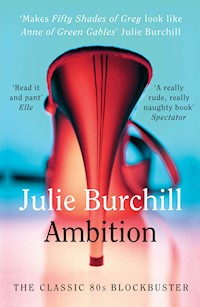

'I'm sick of breaking bimbos - it's no fun, no challenge. Strong, hard career girls - they're the new filet mignon of females. Girls like you. Oh, I'm going to have fun breaking you, Susan.' Tobias Pope ruled his communications empire with fear and loathing - his employees feared him and he loathed them. But he may have met his match in Susan Street, the young, beautiful and nakedly ambitious deputy of his latest newspaper acquisition. As they fight, shop and orgy from Soho to Rio and from Sun City to New York City, getting what she wants - the top job - seems so simple. If she doesn't break first. No taboo is left unbroken, no fantasy left unfulfilled in this shocking exposé of the lengths to which one woman will go become editor of the UK's bestselling tabloid.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2013

Ähnliche

Ambition

Julie Burchill has written more than a dozen books, with the TV adaptation of one of them, Sugar Rush, winning an International Emmy. Her hobbies include spite, luncheon, philanthropy and learning Modern Hebrew. She is married and lives in Brighton. She has been a journalist since the age of 17 and is now 53 years old.

First published in Great Britain in 1989 by The Bodley Head, an imprint of Random House.

This edition published in paperback in Great Britain in 2013 by Corvus, an imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd.

Copyright © Julie Burchill, 1989

The moral right of Julie Burchill to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities, is entirely coincidental.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Paperback ISBN: 978 1 78239 118 0 E-book ISBN: 978 1 78239 117 3 OME ISBN: 978 1 78239 154 8

Printed in Great Britain.

Corvus An imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd Ormond House 26–27 Boswell Street London WC1N 3JZ

www.corvus-books.co.uk

Contents

ONE

TWO

THREE

FOUR

FIVE

SIX

SEVEN

EIGHT

NINE

TEN

ELEVEN

TWELVE

THIRTEEN

FOURTEEN

FIFTEEN

SIXTEEN

SEVENTEEN

EIGHTEEN

NINETEEN

TWENTY

ONE

There were two people in the Regency four-poster that swamped the suite overlooking the Brighton seafront but only one of them was breathing, deeply and evenly, as she sipped flat Bollinger Brut and decided what to do next.

Her name was Susan Street, and she was almost twenty-seven and almost beautiful with long dark hair, long pale legs and a short temper. Beside her lay a man who would never see fifty again and who now would never see sixty either. He had been, until half an hour ago, the editor of the Sunday Best, a tabloid with teeth whose circulation was three million and rising. Unfortunately he would never see it reach four million, because his deputy editor Susan Street had just dispatched him to that big boardroom in the sky with a sexual performance of such singular virtuosity that his heart couldn’t stand it.

His heart, like everything else about him, was weak, she thought as she kissed his still-warm lips.

She jumped from the bed in her Janet Reger teddy, looking like a call girl and thinking like a pimp. She saw herself in the mirror and reflected that the frail garment had to bear at least two-thirds of the responsibility for Charles Anstey’s early death on its flimsy back. Men were so predictable, the helpful little sweeties: they all loved blowjobs, they all loved high heels and they all loved black Janet Reger teddies. If she ever made it up the Amazon and found a tribe totally untouched by both white man and Playboy, she just knew that once you got down to it they too would love blowjobs, high heels and Janet Reger teddies.

It was in the blood and under the skin of men. And who was she to withhold the addictive, destructive drug they craved so badly?

Who was she? She was Susan Street . . .

The smile slid from her face like the scribble from a child’s Magic Slate, shaken suddenly. On her hands and knees she circled the deep pile of the red carpeted room, delicately picking up the small smashed phials which had contained the amyl nitrate. When she had covered the floor twice, she made a tiny glass mountain on a newspaper – yesterday’s copy of the Best – pulled on her lethal red Blahnik heels and ground the glass into a fine powder. For one wild moment she thought of mixing it with talcum, taking it back to town and giving it to her best friend and worst enemy, Ingrid Irving. Ingrid was number three on a vastly more upmarket Sunday, a source of constant irritation and a complete and utter cokehead; her sinuses were so badly shot that she could snort straight Vim without missing a beat.

Then she looked at the man on the bed. She had done enough damage for one day.

Or nine lifetimes.

Grinding down the agent of Anstey’s death on to the paper he had loved so much made her laugh hysterically. Who needs yesterday’s paper, who needs yesterday’s man? She sat down quickly on the bed as though she had received a fatal telegram, fighting her laughter. Tears came to her eyes.

It had been a sort of eternal triangle – not his wife, she wasn’t important. But him, Susan and the Best. They had both loved it, both worked on it together for six years, both taken it so far and planned to take it further. To the top . . .

She jumped up and ran to the bathroom. Cry later. Tears on ice, shaken and stirred. She slid the glass into the bowl and flushed again and again until even the fussiest guest could have drunk their daiquiris from it. Then she walked into the bedroom, summoning back her hysteria. She brought her hands together to make a giant fist and smashed it into her stomach, hard, gasping with pain. Then she screamed, over and over, as (to be careful of her nails) she dialled 999 with the heavy black and gold Mont Blanc pen – Charles’s first-ever present to her.

When the policeman answered, she gasped, ‘Oh please – quickly – there’s been a death, at the big hotel by the West Pier, the really big one . . . yes that one . . . Charles Anstey . . . no, I’m not, I’m an employee. My name is Susan Street. Thank you, yes, as soon as possible.’

She replaced the receiver carefully and smiled at her bright-eyed, wet-lipped reflection. She had never looked better. Wasn’t this the way sappy male writers had their heroines looking after sex? No, sex had never done this for her; just blurred her mascara and kissed away her lipstick. Only power made a girl look this good . . .

‘My name is Susan Street, and I am the youngest ever female newspaper editor in the world.’

The man on the bed jerked one more time, as if in agreement.

She rested her forehead against the window and watched the pretty Sussex countryside go by. All those people in all those houses . . . how many of them were teenage girls dreaming of escape? Thousands. And how many would make it? Not even a hundred.

She felt impossibly tired. Her ordeal, for the moment, was over. The police had seen the stained sheets and her long, long legs in their red shoes. They had listened silently to her tearful recitation of his medical history, including the two small heart attacks before she met him. The younger constable – it was true about the police looking younger – had even gone pink around the edges.

She had mumbled something about his wife in Richmond and it all being horrid.

The older policeman said not to worry, miss, his lad would see to it personally, breaking the news to Madame Anstey. It was all she had been able to do to stop herself jumping up and offering to break the news to Madame Anstey herself: ‘Oh, and by the way, Lorraine . . . his last words were “I’m coming, you bitch . . .” ’

She leaned forward in her First Class train seat like a jockey in sight of the home stretch, urging the iron horse on. Hurry up, please. The country was for cows; the country was where you ran away from, or retired to, not where you lived, when you were young and almost beautiful. She loved the city, she needed the city, she belonged to the city . . .

And now the city belonged to her . . .

Once, all she had had of the city had been a map of the London Underground. In later years, when time had wrapped a tourniquet around the terrible anguish of her adolescence, she would always reply with a straight face, ‘Harry Beck’ when asked which artists she liked. Harry Beck was the man who had designed the map of the London Underground; the map under which she slept, wept and crossed the days off the calendars she kept beneath her winter clothes, as other adolescents kept dirty books. She knew that in the eyes of her friends and family, her maps and calendars would mark her out as being touched with something even worse than nymphomania.

Ambition.

But she slept beneath the map and she dreamed in tube stations: Angel, Marble Arch, White City. Once or twice a year she escaped alone and made the six hour round trip to her promised land where she would roam the streets wide-eyed, her tape recorder in her hand. At night she fell asleep to the sound of London, in dreams she saw it, and in the morning she wept to find herself beached in the backwater of the pretty West Country town she had been condemned to birth in.

But something rubbed off. By the age of fifteen she looked like a citizen of the Borough of Kensington and Chelsea, talked like a citizen of the Borough of Bow and thought like a citizen of the City. By now she knew that the country could never claim her and as if in retaliation the lost souls already sinking into its porous soil turned on the cocky cuckoo in the nest as they sank into the teenage quicksand of fiancé with room-temperature IQ, small screaming vampires in Viyella vests and le petit mortgage.

Right-wing ideas about the bond between people of a similar culture and pigmentation, and left-wing ideas about the bond between women left Susan Street early, flushed down the school toilets her former friends held her head down when they smelled a rat planning to leave the sinking ship of their youth. She was relieved of all illusions before she reached the age of consent, when she shed her tight and shrivelled adolescent skin and emerged as a creature without conscience or scruples, with an almost irritable desire to get on with it. When The Beat ran the advert and she answered it on school notepaper (she could have typed it, but let them drool over her immaculate youth, old crumblies in their twenties who probably thought that teenagers were mythical beast figments of their wildest, wettest rock dreams), and they asked her to write something, and she wrote it in her smudgiest, most schoolgirlish hand and the editor, Sam Kelly, called the principal’s office to summon her from double Maths to offer her the job and she realized she was going to work for the best and biggest music paper in the world, she felt not elation but great relief and something almost like . . . it was . . . disappointment.

It was all so predictable somehow, her irresistible rise. She sat on the principal’s window sill, biting her thumbnail and looking out at the playground where her heart had been broken and her fate had been sealed and she wished that somehow she could have been given some choice in the matter of her ambition and the success it would inevitably bring.

Six weeks later she was sitting in the lap, if not of luxury, then of Gary Pride, sniffing amphetamine sulphate through a fifty-pound note. In theory, she worked at The Beat during the day and slept at the YWCA at night. In fact, she spent the day slouching against the office partitions cleaning her nails with a switchblade and sneering at her colleagues. In later years such action would be known as a ‘career move’.

At night she slept with Gary Pride in his coffin in Limehouse. Gary Pride was a rising young pop star of twenty-two who made awful records which contained the words ‘Pride’, ‘Soul’, ‘Joy’, ‘Respect’ and ‘Dignity’ repeated many times in various permutations. He said they were a homage to Motown. They sounded marginally less black than mid-period New Seekers. That didn’t stop people buying them or Susan sleeping with him. Secretly, she held a deeply felt belief that he should be formally executed for crimes against the memory of black music.

Gary Pride had an ugly face and a beautiful smile which made you forget how basically worthless he was. At least, everyone but Susan. She thought he was a scumbag.

She slept with him because she had quickly learned that a teenage country girl with the legs of a dancer, the behind of a boy and the lips of a Port Said suck artist was a sitting Danish pastry for every disease-carrying flyboy in the shop window, not to mention the streets, offices and subways of the big city. Gary was her protection. By doing one unpleasant thing (Gary) she was made immune to the multitude of unpleasant things she might otherwise be cornered into doing. It was, if you wanted to be vulgar, immunization by injection. In later life she would calculate that at least eighty per cent of the girls she had known had tolerated their boyfriends for this same reason.

Of course, Gary Pride didn’t know this. Like all shallow men he believed in True Love, taken frequently. He wrote songs for her – ‘(I Saw You) Dancing By Your Handbag’ and ‘Never Love A Soulboy’. She was so embarrassed she wanted to die, or preferably to kill him. Instead she accompanied him to the Top Of The Pops studio and to horrible places like Aylesbury where the band always tried out before London. She learned how to ignore the girls who hung around the stage door and spat at the band’s girlfriends, even when it stuck to her face.

‘You’ve got dignity, gel,’ said Gary. (He liked that word.) ‘You’re just like the Queen Mum.’

He stayed faithful, by and large, to her because she was lividly young and pale, still uncalloused inside her Lewis Leathers second skin. Also because she worked on The Beat. (‘Yeah, my girl’s a writer,’ she once heard him boasting to some fellow warbling cretin. ‘Not some record company slag.’)

Also because she had been a virgin.

His first!

He could laugh about it now, which he did loudly and lewdly and often, in front of his entourage, squeezing her thigh and referring smarmily to their first night of passion. It was like living in a Carry On film.

But at the time, he had almost killed her . . .

‘You’re a what?’ Gary Pride jumped from the king-size coffin and stood in the middle of his Limehouse warehouse, naked except for a 666 tattoo on his shoulder.

‘A virgin,’ she whispered. Things had gone very quiet. Everyone was looking.

‘Jesus, Susan!’ He turned on the room, where his entourage lay sprawled on the flagstones watching The World At War with the sound turned down and the 1910 Fruitgum Company on the Dansette, snorting, swigging, guzzling and groping yet another night away. ‘Out, the lot of you liggers! OUT! Before I call the Bill!’

Shooting Susan poison looks, blaming her for displeasing their master and mealticket, the revellers staggered out into the cold night air. Gary Pride bolted the huge doors and stalked purposefully back to the coffin where Susan lay on her back with her eyes closed, trying to make herself look as much like the red silk lining as possible.

‘Susan! God ’elp me, gel, if you don’t open your eyes right now I’ll close them for you permanent!’

She opened her grey eyes wide. The effect she was hoping for was that of those wretched Third World urchins with the big eyes and raggedy clothes in those awful Woolworth’s prints her mother had such a liking for. She couldn’t swear to it, but she thought they were called things like ‘Chico’.

‘Right. Now do you mean to tell me—’ To her horror she noticed he was getting another erection. She hadn’t seen anything so disgusting since her beloved grandmother had given up eating pigs’ trotters on account of her dentures. Gary fastidiously threw a buffalo skin (Magnificent animal, innit, the buffalo? Sorter . . . majestic. Dignifield. I fink I’ll write a song about a buffalo) on to her smooth white body. ‘Do you mean to tell me you are an actual virgin?’

‘Was.’

‘Don’t rub it in, gel!’ He smote himself dramatically. ‘WAS.’

‘Yes.’

‘Oh my God.’ He sank on the stone floor theatrically, then jumped up as the chill flags touched his behind. ‘People think I’m a wild sort of guy. I guess I am.’ (He always assumed an American accent when talking about himself.) ‘But I got my own code of honour. And do you know what the number one rule on my code of honour is?’ He paused, one hand in the air, like Simon Rattle about to strut his stuff.

‘No, Gary,’ she whispered. She had always envisaged that getting shot of her virginity would be like having a tooth out: painful, boring, but basically banal and hopefully over quite quickly. She hadn’t expected a cross between Twenty Questions and Armageddon.

‘I don’t sleep with virgins, that’s what!’ He glared vengefully.

‘I’m sorry, Gary.’ She thought he might strike her.

‘ ’Ow was you to know?’ He looked at her with weary compassion. ‘You ever read any books about knights?’

‘Only Ivanhoe, at school.’

‘That’s bollocks. You wanna read the real stuff . . . the Crusaders, the Knights of Simon Templar . . . magic! Well, I see myself as a sort of urban parfait knight. You know what that is?’

‘No, Gary.’

‘They got a code, like all outlaws.’ He thrust out his jaw, looking like something on loan from the Natural History Museum. ‘AND VIRGINS IS RIGHT OUT!’

‘I’m sorry, Gary.’

He shook his head with infinite wisdom. ‘ ’Ow was you to know? You’re a good gel, Susan.’ He lifted the buffalo skin and looked at her body, the gleam of infinite lechery dawning in his bloodshot eyes. Suddenly he vaulted back into the coffin, showing a remarkable agility. ‘Might as well be hanged for a sheep as a lamb, I suppose!’

Before the night was over she was sitting on his face. Now she was sitting on his lap in his dressing room after a show at the Hammersmith Odeon, and he was shoving her towards an exotic-looking girl with a nose-ring. What a fucking parfait knight he was.

‘I fancy a nice bit of dyke action,’ he was whispering. Charming.

The crowd did a passable impersonation of après-ski Red Sea as Susan and the girl slid to the floor.

‘What’s your name?’

‘Shira.’

‘Mine’s Susan.’

‘Yes, I know. I see you around with the band.’

‘Weren’t you in Birmingham the other night?’

‘Yes, right, when you . . . ’

‘Jesus H!’ yelled Gary Pride. ‘You want the room cleared so you can tell each other your life stories? Now eat it!’

The two girls slipped from their scuffed leather skins, under which they were naked. The silence dripped saliva. Shira had surprising emerald-green pubic hair and a tattoo just below her navel warning KEEP OFF THE GRASS. Susan got down to grazing, with a vengeance.

Gary Pride bought time.

He bought friends.

He bought a season ticket to Highbury, but he didn’t dare go. (More than my life’s worth. I’d be ripped apart by the love of my people.)

He bought books on the English Civil War, the code of the Samurai and the decline and fall of the Roman Empire, but he never read them. (Life’s too short, innit? Look, the snooker’s on.)

He bought suits of armour. Of course he never wore them. When they began to collect dust he had them packed in a crate and sent to his family in Kent. (He claimed to be a Cockney; it was his whole raison d’être. His first album was called ‘Cockney Pride’. There must have been a strong wind blowing south from the vicinity of Bow Bells the day Gary Pride was born, Susan secretly thought.)

He bought lutes, mandolins and lyres and threw them down in fits of pique when they failed to respond in exactly the same way as a 1976 Fender bass.

But most of all, he bought drugs. And these he certainly knew what to do with. Hash, speed, cocaine, opium and LSD. It was the acid that broke the cretin’s back. He woke up in the coffin one morning screaming about the Rotarians. And the Freemasons. And the Tongs. Through a lurching amphetamine fog hangover Susan saw him pull on his nearest clothing (a Samurai ceremonial robe – was he going to get stopped at Customs!) and rifle through the bureau for his passport. She never heard from him again. A month or so later his record company told her he had gone to the volcanic island of Vanuatu to get his head together.

She was eighteen and sick to the back teeth of asking crooning morons too stoned to remember their own phone numbers what their views were on the situation in Rhodesia, which had become as essential to a Beat interview as a favourite colour was to the teenybopper magazines. If you failed to ask them to their stupid faces you had to call them at home and pop the question, and doing it in isolation made you feel even dumber. Then a posh cow called Rebecca called her at the office one day and asked if they could have a drink.

In a bar in Jermyn Street Rebecca sighed deeply into her Kir Royale and murmured something about New Blood. About the Street. About the Blank Generation. Susan watched, fascinated. Rebecca talked into her drink like a ventriloquist drinking a glass of water while screeching ‘Gottle of geer!’ and sounded like a Labour Party Manifesto. Then suddenly she rounded on Susan, looking her straight in the eye, and said in a completely different, mid-Atlantic voice, ‘Well?’

‘Sorry?’

‘Fifteen thousand a year, pathetic really, no car, expenses, as much depilatory as you can use and endless free samples, well, of everything really.’ Rebecca fished in her Fendi bag and threw a glossy magazine on to the bar. A girl in a tux pouted furiously at them. PARVENU. ‘We’ll call you associate ed, if you want. Doesn’t mean anything. But everyone else is an editor, even the messenger, so you might as well be.’ Her mission complete, Rebecca wilted elegantly again and began to murmur into her cocktail about Working Class Energy.

Susan knew of Parvenu. It was a magazine which proclaimed, subtitled on the cover of every issue, ‘LIFE IS A PARTY’. It was frivolous, snobbish and shallow. But after The Beat, where thirty-year-old men looked for the meaning of life in plastic platters, it came as a breath of fresh carbon monoxide. So she murmured into her Black Russian about a Time For Everything and the New Selfishness. Displaying a healthy measure of it, Rebecca shot off five minutes later leaving Susan to pay for the drinks.

In her two years at Parvenu Susan learned how to call dinner lunch, how to call enemies ‘Darling’, how to dress, how to drink and how to tell the perfect lie. She also learned things about men that made Gary Pride look like a verger.

One afternoon after a fashion shoot she went to bed with three male models. In the morning one of them asked her if she had ever done it with an Afghan.

‘Guerrilla?’

He ruffled her hair and laughed. ‘Hound, silly.’

Then she interviewed a hot young actor at a hotel in Kensington. They stayed in his room for a week, ordering cocaine, champagne and caviar from the hotel’s various pantries. On the day of his departure he was very quiet. He didn’t look at her as he packed and she guessed that he was already psyching himself into his next role: that of loving, faithful boyfriend to the filthy rich Manhattan heiress he was engaged to.

‘Aren’t you going to give me anything to remember you by?’ she finally asked flirtatiously and desperately from the bed.

He pulled on his cowboy boots, stood up and looked down at her. ‘I have,’ he said quietly. ‘Herpes.’ Then he was out of the door, carrying the one canvas tote bag that made up his luggage, a man-of-the-people affectation that had charmed her a week ago and now revolted her.

It took two weeks, a week’s wages and a private clinic before she was sure he was just a sadist with a kooky sense of humour. Herpes was the new urban folk demon; people told jokes against it as if to inoculate themselves. What do the couple who have everything have embroidered on their towels? ‘HIS’ and ‘HERPES’.

She shared a flat in SW10 with a cousin of Isabella’s, the girl at the next desk in the Parvenu office. The girl called herself Trash. She was impossibly rich, had five A-levels and worked in an Arab clip joint in W1. Her family were related by marriage to a certain Family who shall be nameless and blameless. She wore her evening clothes only once: on coming home, around four in the morning, she dropped them into the matt black dustbin as other more frugal girls might drop them carelessly on to the floor after a hard day at the office. Occasionally, she burned that night’s dress in the sink, scat singing arias from Madame Butterfly as she did so.

Trash had two hyphens, not one, in her surname. Susan once didn’t see or hear her for six weeks. They never talked. Trash seemed to regard conversation as a breach of good manners. Once Susan, a little drunk and lonely, stopped her as they passed in the hallway and asked her why she needed a flatmate. Trash smiled like a game-show host.

‘Because I can’t stand a cold toilet seat.’

When she killed herself in the bath one Monday morning, Susan discovered that Trash had really been Georgia. ‘But I always called her Trash!’ she said to Isabella as they waited for the lift down one night. Somehow it seemed very important.

Isabella smiled absently. ‘Oh, don’t worry. Everyone called her Trash. Even her ma.’

‘That’s not the point.’

‘Sorry?’

Who, what, why, where, when? This was supposed to be the mantra of journalism. It went through her head, more and more, like the slick black backbeat of a soul song. She couldn’t answer any of them. She read cereal packets and racing results to find an answer. She spent a preternatural amount of time listening to the lyrics of popular songs. A song called ‘Boogie Oogie Oogie’ drove her to distraction for a few weeks; she bought the single and stayed at home in the evenings with the stylus on auto, listening to it fifty times in a row. She was convinced it was trying to tell her something.

She got drunk every night and every morning woke up with a headache where her memory had once been. The thought of suicide was always there, comforting, like old money to be fallen back on in desperate times. Sometimes only the thought of death made life bearable. A greyhound winner called Too Much Too Young made her laugh for half an hour. WHO, WHAT, WHY, WHERE, WHEN?

Then she met Matthew.

Matthew Stockbridge sat at his desk in the big South London hospital and looked across at the pretty, sick-looking girl who was trying to insert a cheese sandwich into her tape recoder.

‘I’m ver’ sorry,’ she slurred. ‘Some sort of malpractice.’

He laughed, a little shocked. ‘No, Miss Street, you came here to ask me about malpractice suits. Didn’t you?’

‘Malpractice. No, malfunction.’ She dropped the sandwich on to the desk and stared at it. ‘Oh look,’ she said brightly. ‘I wondered where that got to.’ She looked up at him, her pupils almost completely covering her grey irises.

‘Miss Street, which drug are you on?’

She rifled through her bag and triumphantly shoved a twist of foil under his nose. ‘Sulphate. Almost pure. Want some?’

‘No thank you.’

Now she was gazing over his shoulder into the far corner of the room with something between amusement and terror.

‘What’s wrong?’

‘There’s a bird in that corner. It’s the Roadrunner,’ she said matter-of-factly.

‘Really?’

‘Oh yes. It’s the Roadrunner and it’s doing the Charleston.’

‘Miss Street, I assure you it’s not. It’s amphetamine sulphate, which has gone to your liver and been transformed into mescalin due to extreme abuse and lack of food and sleep. Am I right?’

She smiled knowingly at him. Then she leaned across the desk and shot the best part of the litre bottle of Perrier water she had been drinking into his lap. Then she began to laugh, so hard that she fell off her chair. She lay on her back, retching up a vile yellow bile and laughing.

Matthew Stockbridge dodged around the desk and knelt beside her. She looked at him.

‘Who, what, why, where, when?’ she asked weakly.

‘Whatever you want.’ He laughed too. ‘It’s all right now, Susan.’

That had been seven years ago. Time, the great vandal, had had its bash at them, and love had gone about halfway through, but she still hadn’t got around to moving out. When you were both busy moderns, there was very little time for elaborate things like leaving. You were always too busy buying things and signing things and throwing things, from dinner parties to dishes. There weren’t enough hours in the day for you to move out. Even when everything else had gone.

She was twenty when she met Charles Anstey, a man with a mission to take the void out of tabloid, at London Fashion Week. He was with his tall, dark and ugly clothesaholic French wife Lorraine. Twenty years ago she must have seemed like good value to a provincial boy in the outer suburbs of his youth but now she had the bitter, disappointed face and grudgingly anorexic body of the fading fashion victim in danger of becoming a fashion fatality.

They sat on either side of Charles, Lorraine nagging for clothes, Susan hustling for a job, like cross caricatures of pre- and post-feminist woman.

‘The young reader,’ Susan elaborated enthusiastically, telling him things he knew already but doing it in such an excited way that he couldn’t help but nod seriously, ‘that’s what you want – no one needs a dying readership. Get them young. And the women readers – don’t marginalize them. Think about them on every page. Newspapers aren’t just about news any more. You should be taking readers from the women’s magazines – not just from each other.’

She never found out if Lorraine got what she wanted from Charles Anstey – but she did. A week later he called her at Parvenu and asked her if she would like a job as a feature writer on the new Sunday Best.

She was a good journalist, but not that good. She had once thrown a scare into a rentboy trying to sell the dirt on a Labour MP just because she was young and idealistic and believed in the things he stood for. And because he was fun to lunch. She wouldn’t do that now, she thought. And a really good tabloid reporter would never have done it. She had been pleased when promotion to features editor lifted her out of the scramble for stories. And then for almost two years she had been deputy editor and next in line to the editor’s chair. Until now.

She was jolted in her seat and out of her dreams. The train had arrived.

And so had she.

TWO

The next day was a Tuesday, first day of the working week for the Sunday papers. She slept like a baby one hour sleeping, one hour crying, and so on rose early and dressed carefully.

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!