Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Atlantic Books

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

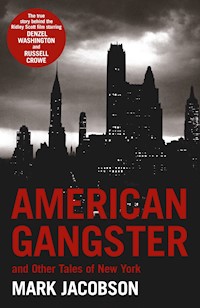

The untold story of Frank Lucas, New York's most notorious drugs lord during the 1970s. Now a blockbuster movie, directed by Ridley Scott and starring Denzel Washington and Russell Crowe. In 1970s New York, the ruthless Frank Lucas was the king of the Harlem drug trade, bringing in more than a million dollars a day. At the height of his power there were so many heroin addicts buying from him on 116th Street that he claimed the Transit Authority had to change the bus routes. Lucas lived a glamorous life, hobnobbing with sport stars, musicians, and politicians, but he was also a ruthless gangster. He was notorious for using the coffins of dead GIs to smuggle heroin into the United States and before his fall, when he was sentenced to 70 years in prison, he played a major role in the near death of New York City. In American Gangster, Marc Jacobson's captivating account of the life of Frank Lucas (the basis for the forthcoming major motion picture) joins other tales of New York City from the past thirty years. It is a vibrant, intoxicating, many-layered portrait of one of the most fascinating cities in the world from one of America's most acclaimed journalists.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 499

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2009

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

AMERICAN GANGSTER

MARC JACOBSON is the author of 12,000 Miles in the Nick of Time: A Semi-Dysfunctional Family Circumnavigates the Globe, Teenage Hipster in the Modern World, and the novels Gojiro and Everyone and No One. He has been a contributing editor to Rolling Stone, Esquire, Village Voice and New York Magazine.

Also by Mark Jacobson

Novels

Gojiro

Everyone and No One

Non-fiction

Teenage Hipster in the Modern World: From the Birth of Punk to the Land of Bush, Thirty Years of Apocalyptic Journalism

12,000 Miles in the Nick of Time:

A Semi-Dysfunctional Family Circumnavigates the Globe

The KGB Bar Non-fiction Reader (edited)

American Monsters (edited, with Jack Newfield)

AMERICAN GANGSTER and Other Tales of New York

MARK JACOBSON

Foreword by Richard Price

Atlantic Books

London

First published in the United States of America in 2007 by Grove/Atlantic Inc.

First published in paperback in Great Britain in 2007 by Atlantic Books, an imprint of Grove/Atlantic Ltd.

This electronic edition published in Greate Britain in 2009 by Atlantic Books, an imprint of Grove/Atlantic Ltd.

Copyright © Mark Jacobson 2007 Foreword copyright © Richard Price 2007

The moral right of Mark Jacobson to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Acts of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

Every effort has been made to trace or contact all copyright-holders. The Publishers will be pleased to make good any omissions or rectify any mistakes brought to their attention at the earliest opportunity.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN: 978 1 84887 265 3

Atlantic Books An imprint of Grove Atlantic Ltd

Contents

Foreword by Richard Price vii

Never Bored: The American Gangster, the Big City, and Me ix

UPTOWN

1 The American Gangster, a.k.a. The Haint of Harlem, the Frank Lucas Story 3

2 The Most Comfortable Couch in New York 36

3 The Wounds of Christ 41

4 Zombies in Da Hood 51

5 Chairman of the Money 56

DOWNTOWN

6 Is This the End of Mark Zero? 73

7 Ghost Shadows on the Chinatown Streets 78

8 From the Annals of Pre-gentrification: Sleaze-out on East Fourteenth Street 101

9 Terror on the N Train 122

10 Re: Dead Letter Department, Village Voice 126

11 Ground Zero/Grassy Knoll: 11 Bulletpoints About 9/11 Truth 144

ALL AROUND THE TOWN

12 Night Shifting for the Hip Fleet 175

13 The Last Irish Cowboy 187

14 The Ear of Sheepshead Bay 194

15 Wynton's Game 201

16 The Champ Behind the Counter 220

17 Mom Sells the House 226

18 The Boy Buys the Wrong Hat 237

19 The $2,000-an-Hour Woman: A Love Story 242

Afterword 267

Foreword

I've always felt that the only subjects worth writing about were those that intimidated me, and the only writers worth emulating were those who left me feeling the same way. I've felt intimidated by Mark Jacobson since 1977 when I first read "Ghost Shadows on Chinatown Streets," his portrait of gang leader Nicky Lui, in the Village Voice. I remember being overwhelmed by both Jacobson's reporting skill and his intrepidness, empathizing with his attraction to the subject; could see myself attempting something like that if I had both the writing chops and the nerve. It was one of the most humbling and enticing reading experiences of my life, and in many ways set me on the path to at least three novels.

Jacobson belongs to that great bloodline of New York street writers from Stephen Crane to Hutchins Hapgood to Joseph Mitchell, John McNulty, and A. J. Liebling, through Jimmy Breslin and Pete Hamill, and now to himself and very few others (his friend and peer Michael Daly comes to mind). Jacobson is drawn to these streets and to those who rose from them: the outlaws, the visionaries, the hustlers, and the oddballs. His voice is often sardonic, bemused, and a little in awe of the man before him. Like a judo master, he knows how to step off and let the force of these personalities hoist their own banners or dig their own graves. But even in the case of the most heinous of men, Jacobson's ability to unearth some saving grace, some charm, or simply a shred of sympathetic humanity in the bastard is unfailing.

From heroin kingpin Frank Lucas to the Dalai Lama, Jacobson's fact-gathering is impeccable, his presentation of the Big Picture plain as day, the conversations (you can't really call them "interviews") often hilarious. Most important, though, his love for this world, these people, is apparent in every nuance, every finely observed detail. His is the song of the workingman, the immigrant, the street cat, the cryptician with more crazy-eights than aces up his sleeve, and Jacobson knows that the bottom line for this kind of profiling is self-recognition; each character, each sharply etched detail in some way bringing home not only the subject, but the reader and author, too.

—Richard Price

Never Bored: The American Gangster, the Big City, and Me

I was born in New York City in the baby boom year of 1948 and lived here most of my life. I started my journalism career back in the middle 1970s, writing more often than not about New York. There have been ups and downs over the past thirty years, but I can't say I have ever been bored. After all, the Naked City is supposed to have eight million stories and, as a magazine writer, I only need about ten good ones a year. So I can afford to be picky. Whether I've been picky enough—or managed to tell those stories well enough—you can decide for yourself by thumbing through this book. That said, some stories are just winners, fresh-out-of-the-blocks winners. The saga of Frank Lucas, Harlem drug dealer, reputed killer, and general all-around enemy of the people, was one of those stories.

An odd thing about the genesis of my involvement with Lucas is that I'd always been under the impression he was something of an urban myth. That was my opinion when Lucas's name came up in a conversation I was having half a dozen years ago with my good friend, the late Jack Newfield. Newfield said he'd seen Nick Pileggi, the classic pre-Internet New York City magazine writer who had been smart enough to get out at the right time, making untold fortunes writing movies like Goodfellas. Nick had mentioned to Jack that Lucas was alive and living in New Jersey.

"You mean, Frank Lucas, the guy with the body bags?" I asked Newfield, who said, yeah, one and the same. This was a surprise. Anyone who had their ear to the ground during the fiscal crisis years of the 1970s, those Fear City times when New York appeared to be falling apart at the seams, remembered the ghoulish story of thousands of pounds of uncut heroin being smuggled from Southeast Asia in the body bags of American soldiers killed in the Vietnam War. The doomsday metaphor—death arriving wrapped inside of death—was hard to beat, but this couldn't really be true, could it?

This was one of the first things I asked Lucas when, after much hunting, I located him in downtown Newark. "Did you really smuggle dope in the body bags?" I asked Frank, then in his late sixties, living in a beat-up project apartment and driving an even more beat-up 1979 Caddy with a bad transmission.

"Fuck no," responded Lucas, taking great offense. He never put any heroin into the body bag of a GI. Nor did he ever stuff kilos of dope into the body cavities of the dead soldiers, as some law enforcement officials had contended. These were disgusting, slanderous stories, Lucas protested.

"We smuggled the dope in the soldiers' coffins," Lucas roared, setting the record straight. "Coffins, not bags!"

This was a large distinction, Frank contended. He and his fellow "Country Boys" (he only hired family members or residents of his backwoods North Carolina hometown) would never be so sloppy as to toss good dope into a dead guy's body bag. They took the trouble to contact highly skilled carpenters to construct false bottoms for soldiers' coffins. It was inside these secret compartments that Lucas shipped the heroin that would addict who knows how many poor suckers. "Who the hell is gonna look in a soldier's coffin," Lucas chortled rhetorically, maintaining that his insistence on careful workmanship showed proper deference to those who had given their life for their country.

"I would never dishonor an American soldier," Frank said, swearing on his beloved mother's head as to his "100 percent true red, white, and blue" patriotism.

Frank and I spent a lot of time together back in the late winter and spring of 2001 as he told me the story of his life. It took a lot to make him the biggest single Harlem heroin dealer in the 1970s, and Lucas was determined that I know it all, from the first time he robbed a drunk by hitting him over the head with a tobacco rake outside a black-town Carolina whorehouse, to his journey north where he would become the right-hand man of Bumpy Johnson, Harlem's most famous gangster, to the heroin kingpin days, when he claimed to clear up to a million dollars a day.

Declaring he had "nothing but my word," Frank said every little bit of what he said was true. This I doubted, even if some of his most outrageous statements seemed to bear out. Most of the tale, however, was hard to pin down. When it comes to black crime, organized or not, there are very few traditional sources. I mean, forty years after the alleged fact, how do you check whether Frank really killed the giant Tango, "a big silverback gorilla of a Negro," on 116th Street? Some remembered Lucas being with Bumpy the day the gangster keeled over in Wells' Restaurant. Some didn't. The fact that Frank can't read (he always pretended to have forgotten his glasses when we went out to his favorite, TGI Friday's) didn't matter. We were in the realm of oral history narrated by some of the twentieth century's most flamboyant bullshitters and Frank Lucas, with "a PhD in street," can talk as well as anyone.

Even though I often employed the phrases "Frank claims" and "according to Lucas" when writing the piece, the tale's potential sketchiness did little to undercut what I always took to be its cockeyed verisimilitude. The enduring importance of Lucas's story can be found in the indisputable fact that very few people on earth could reasonably invent such a compelling lie about this kind of material. If nothing else, Lucas is a knowing witness to a time and place inaccessible to almost everyone else, and that goes double for white people. The verve with which he recounts his no doubt self-aggrandizing story is an urban historian's boon, a particular kind of American epic. I considered myself lucky to write it down.

Now, Frank's life, or at least some highly reconfigured version of it, will be on display in the big-budget Hollywood picture American Gangster, with Denzel Washington, no less, playing the Frank part. By the time they get done advertising the film, which also features Russell Crowe and was directed by Ridley Scott, something like $200 million will have been spent to bring Frank's story to the silver screen, which might even be as much money as Lucas made pushing drugs all those years. By the time you read this Frank Lucas will be perhaps the best-known drug dealer ever.

There is a bit of irony in this, since back in The Day, Lucas's claim to fame was that he had no fame. While rivals like Nicky Barnes were allowing themselves to be photographed on the cover of the New York Times Magazine section and claiming to be "Mr. Untouchable," Frank kept studiously below the radar. He trusted no one, and almost always appeared on 116th Street, his primary stomping ground, in disguise. With the release of the film, however, Frank, now in his seventies and confined to a wheel-chair, will have his picture taken by hundreds of Hollywood photographers. Knowing him, he'll go with the flow, laughing his blood-curdling laugh and gloating about how great it is "to be on top again."

To have shared this Hollywood business with Frank has been a whole other trip. After Imagine Pictures optioned the story and Frank's "life rights," we were flown out to Los Angeles. How marvelous it was to sit with Frank and Richie Roberts, the man who prosecuted Lucas in the Essex County courts (Russell Crowe plays him in American Gangster) in a big-time meeting with the brass from Imagine and Universal Pictures. Seated around a long conference table, Lucas leaned over to me and asked, "Who's the guy in the room with the juice?" I told him it was "the one with wacked-off hair and the skinny tie," that is, überproducer Brian Grazer.

"That guy? No way," scoffed Frank. "What about him?" Lucas asked, pointing to a dark-haired thirty-year-old wearing an expensive Rolex. "He's just a studio flunky who is going to be fired next week," I informed Lucas, again telling him Grazer was the guy.

An hour later, when the meeting was over, Lucas, nothing if not a quick study when it comes to power relationships, came over to me and said, "You know something, Mark? I thought I was in a rough business, but these people are off-the-hook sharks."

Richie Roberts, now an attorney handling criminal cases in North Jersey's Soprano belt (he was once the star running back at Newark's Weequachic High School, where he passed, and ignored, Philip Roth in the hallways) has known the old drug dealer for more than thirty years. The producers of American Gangster have hung much of their film on the relationship between the two men.

"Frank, Frank and me … that is a long story," says Roberts, who has decidedly mixed feelings about his relationship with Lucas. "I know who he is, the horrible things he'd done. Don't forget, I put him in jail. And if there's anyone who deserved to got to jail it was Frank Lucas. I was proud to get him. I'm still proud of it.… As for us being such good friends, I don't know if I'd call it that. He has a young kid, Ray. When he was little I paid for his school tuition. I really love that kid. As for Frank, let's say he's a charming con man. But even knowing everything I know, God help me, sometimes I just can't help liking the guy."

As you will see from reading the piece, Lucas has always relied on his ability to make people like him. "People like me, they like the fuck out of me," he says, cackling. I had to agree. There I was, sitting and listening to him talk about all the people he had murdered, how his brother, Shorty, used to delight in holding enemies by their ankles over the railing of the George Washington Bridge. He said they better talk or he'd drop them. They'd talk and Shorty would drop them anyway. Of course, Lucas was a miserable human being. On the other hand, he was giving me a heck of a story. And, to be honest, I liked the guy. I liked the fuck out of him.

The movie business cut into this. From the get-go, I told my agent that if a deal was to be made, my interests had to be separate from Frank's. "I don't want to be in business with him," I said. Yet, somehow, this never got done. Now the money was on the table, waiting to be split up by me and my new partner, Frank Lucas.

When Frank called me one morning and said to come on over so "we can talk this thing out like men," my wife, who upon hearing the tapes of our interviews had asked "Who you doing a story on, Satan?" told me not to go. She didn't think I should talk about money with Frank. That was what lawyers were for, she said. I told her not to worry. Frank and I were friends. Buddies. I'd been over to see him in Newark a dozen times. Why should this be different?

I began to notice something might be amiss when I entered the restaurant and was told Frank was waiting for me in the back room. Lucas was sitting at a table off to the side. Against the wall were a few guys, big guys. I'd seen them before, on and off. One, Lucas's nephew Al, about six-foot-seven, 240 pounds, had played football in the arena league. Al and I were friendly. I'd given him rides to the City a couple times. We'd smoked weed together, had some laughs. Now, dressed in black leather, Al stood impassively behind Frank. When I said hello, instead of his usual ghetto bear hug, there was only a curt nod.

"What's this about, Frank?" I asked.

"It's about I got to have all the money," Frank said, smiling.

"All of it?" I'd already decided to give Frank a larger share. It was his life they were buying after all. But all?

"You can't have it all," I said. "That wouldn't be fair."

"Don't care if it's fair. I got to have it all," Frank repeated, leaning forward. Once, when Lucas and I were riding around in Newark, he told me to drive over near a nasty-looking bunch of guys hanging out on a street corner. "Open the window and shout, hey you," Lucas demanded. When I protested, he screamed, "Just do it." I did. The guys froze. "Tell them to come over," said Lucas, now crouching under the dashboard. When I didn't he yelled, "Get your black asses over here." The bad guys complied, nervously. When they got close Lucas sprang out and screamed, "Boo!"

"Uncle Frank!" the guys screamed, cracking up. Being as I was white, there was no reason for me to be in that neighborhood unless I was a cop. Scaring the guys was Frank's idea of a joke.

This money demand could be one more laugh, but I didn't think so. This was another kind of Frank Lucas, not the semi-lovable historical figure for whom I'd bought all those pitchers of Sam Adams. It occurred to me that long after my story about him was written and published, I'd missed a good portion of what I'd set out to find. It wasn't until that very moment that I saw the real Frank Lucas, or at least the part of him that enabled all those nefarious deeds I'd been so enthralled to hear about. Eyes set, mouth motionless, for the first time he looked like the stone killer I knew him to be.

Frank had a piece of paper the agent had sent over. We were supposed to fill in what percentage of the option money each of us would get. Frank suggested I write "zero" next to my name.

At this point, I suppose, I could have told Frank Lucas that if it wasn't for me, he wouldn't be on the road to having Denzel Washington be him on the silver screen. If it wasn't for me, he'd still be up there in his rat hole project apartment, where the only place to sit was on those five-foot-high red vinyl bar stools he'd obviously got off a truck somewhere. But I didn't.

"Look, Frank," I said. "I'm gonna get up and go back to my car. Then I'm going to drive back to the City. We can work this out later, okay, on the telephone."

So maybe Frank had lost a step or two, or maybe he wasn't as hard as he made himself out to be, because no one jumped me. I didn't take a shiv in the back. Probably the wily old operator realized that wouldn't have served any purpose, since the paper required both of our signatures. If I was dead, I wouldn't be able to sign. Then Frank would get nothing.

This became the strategy: I wouldn't sign. I figured I could live without the money longer than Frank could. One day I told him he could have one more percent than me, and he agreed. All of a sudden, we were cool again, just like before. I heard Frank bought himself a brand-new SUV with some of his take and smashed it up the very next week. That was too bad, I thought. Because when it comes down to it, I like Frank. I like the fuck out of him.

All in all, American Gangster has been a winning experience for me. Better than the usual dealings I've had with Hollywood. The producers bought my story. I got paid. I didn't have to do anything but cash the check. This is good. Most times when Hollywood guys buy the rights to these journalism stories—as they often do—things don't go so smoothly. Years ago some guys took an option on a piece I wrote about the New York City high school basketball championship, Canarsie High School vs. Lafayette, both of them from Brooklyn, and hard-nose. The story, written in 1976, took a while to "set up." In 1992, the buyers said it finally looked like a go, except now the story had been changed some. Now it was about two girls softball teams in Compton, California. They hoped I didn't mind. Why should I mind? As a big NWA fan, Compton softball sounded great to me. Needless to say, nothing ever happened.

This said, the specter of Frank Lucas, icon of a New York City that no longer exists, hangs over this entire collection of stories. It is like Frank says about how he feels going into a giant Home Depot. In his gangster days whenever he walked into any bank or store—anyplace where they had money—he'd reflexively figure what he'd do if he wanted to rob the place. But at Home Depot, he was stumped. The place was so big, so decentralized, confusing.

"You don't know where to stick the knife in," Frank allowed dejectedly, as if the changing times had just passed him by.

Reading over many of the pieces in this book, I wonder if that is true for me as well. After all, much of the stuff I write about here either no longer exists, or has changed irrevocably. Little of this change is to my liking. Not that it hurts the work since in New York, the journalist accepts that what he writes about today may not be there tomorrow. All you can do is try to capture what's put in front of you, on the day you're looking at it. Once the parade passes by, the work becomes part of urban history. Besides, there's plenty new around that isn't owned by some tinhorn condomeister. Those supposed eight million stories have become twelve million, maybe even fourteen if you count all those Mexican soccer fans out in Queens. That should be enough to keep anyone busy.

No introduction is complete without the usual-suspect acknowledgments. For the most part the pieces in this book are different from the ones that appeared in the first collection of my journalism, The Teenage Hipster in the Modern World, but most of the thank-yous remain the same. Special shout-outs to Morgan Entrekin, the publisher of this book, John Homans, editor of many of these pieces, Caroline Miller, and Adam Moss, boss of New York magazine, who continues to enable my health plan. Ditto the wife and kids. But tell me, how mauldin is it to thank the City itself: always my inspiration, mentor, and antagonist.

Mark Jacobson, 2007

UPTOWN

1The American Gangster, a.k.a. The Haint of Harlem, the Frank Lucas Story

Face-to-face with the charming killer. If Frank wasn't born black and poor, he could have been a really rich, corrupt politician. Instead, he became a really rich drug dealer. But he did call his mom every day. An epic tale of the vagaries of race, class, and money in the U.S. of A, this is the basis for the Ridley Scott film, American Gangster, with Denzel Washington in the Frank role. As Frank says, "I always knew my life was a movie," even if he saw himself as more of the Morgan Freeman type. "Denzel, however, will do." From New York magazine, 2000.

During the 1970s, when for a graffiti-splashed, early disco instant of urban time he was, according to then-U.S. District Attorney Rudolph Giuliani, "the biggest drug dealer" in Harlem, Frank Lucas would sit at the corner of 116th Street and Eighth Avenue in a beat-up Chevy he called Nellybelle. Then residing in a swank apartment in Riverdale down the hall from Yvonne De Carlo and running his heroin business out of a suite at the Regency Hotel on Park Avenue, Lucas owned several cars. He had a Rolls, a Mercedes, a Stingray, and a 427 four-on-the-floor muscle job he'd once topped out at 160 miles per hour near Exit 16E of the Jersey Turnpike, scaring himself so silly that he gave the car to his brother's wife just to get it out of his sight.

But for "spying," Nellybelle worked best.

"Who'd ever think I'd be in a shit three-hundred-dollar car like that?" asks Lucas, who claims that, on a good day, he would clear up to a million dollars selling dope on 116th Street. "I'd sit there, cap pulled down, with a fake beard, dark glasses, maybe some army fatigues and broken-down boots, longhair wig … I used to be right up beside the people dealing my stuff, watching the whole show, and no one knew who I was.…"

It was a matter of control, and trust. As the leader of the "Country Boys" dope ring, Frank, older brother to Ezell, Vernon Lee, John Paul, Larry, and Lee Lucas, was known for restricting his operation to blood relatives and others from the rural North Carolina backwoods area where he grew up. This was because, Lucas says in his downhome creak of a voice, "A country boy, he ain't hip … he's not used to big cars, fancy ladies, and diamond rings, so he'll be loyal to you. A country boy, you can give him a million dollars, five million, and tell him to hide it in his old shack. His wife and kids might be hungry, starving, and he'll never touch your money until he checks with you. City boy ain't like that. A city boy will take your last dime and look you straight in the face and swear he ain't got it.… A city boy'll steal from you in a New York minute and you've got to be able to deal with it in a New York second.… You don't want a city boy, the sonofabitch is just no good."

But trust has its limits, even among country boys, Frank says. "A hundred sixteenth between Seventh and Eighth Avenue was mine. It belonged to me.… I bought it. I ran it. I owned it. And when something is yours, you've got to be Johnny on the Spot, ready to take it to the top. So I'd sit in front of the Roman Garden Restaurant, or around the corner by the Royal Flush Bar, just watching."

There wouldn't be much to see until four in the afternoon, which was when Frank's brand of heroin, Blue Magic, hit the street. During the early seventies there were many "brands" of dope in Harlem. Tru Blu, Mean Machine, Could Be Fatal, Dick Down, Boody, Cooley High, Capone, Ding Dong, Fuck Me, Fuck You, Nice, Nice to Be Nice, Oh—Can't Get Enough of that Funky Stuff, Tragic Magic, Gerber, The Judge, 32, 32-20, O.D., Correct, Official Correct, Past Due, Payback, Revenge, Green Tape, Red Tape, Rush, Swear To God, PraisePraisePraise, KillKillKill, Killer 1, Killer 2, KKK, Good Pussy, Taster's Choice, Harlem Hijack, Joint, Insured for Life, and Insured for Death are only a few of the brand names rubber-stamped onto the cellophane bags.

But none sold like Blue Magic.

"That's because with Blue Magic you could get ten percent purity," Frank Lucas asserts. "With any other if you got five percent you were doing good. Mostly it was three. We put it out there at four in the afternoon, when the cops changed shifts. That gave you a couple of hours to work, before those lazy bastards got down there. My buyers, though, you could set your watch by them. Those junkies crawling out. By four o'clock we had enough niggers in the street to make a Tarzan movie. They had to reroute the bus coming down Eighth Avenue to 116th, it couldn't get through. Call the Transit Department to see if it's not so. On a usual day we'd put out maybe twenty-five thousand quarters (quarter "spoons," fifty dollars' worth, enough to get high for the rest of the day). By nine o'clock I ain't got a fucking gram. Everything is gone. Sold … and I got myself a million dollars."

"I'd just sit there in Nellybelle and watch the money roll in," says Frank Lucas of those not-so-distant but near-forgotten days, when Abe Beame would lay his pint-sized head upon the pillow at Gracie Mansion and the cop cars were still green and black. "And no one even knew it was me. I was a shadow. A ghost … what we call downhome a haint … That was me, the Haint of Harlem."

Twenty-five years after the end of his uptown rule, Frank Lucas, now sixty-nine, has returned to Harlem for a whirlwind retrospective of his life and times. Sitting in a blue Toyota at the corner of 116th Street and what is now called Adam Clayton Powell Boulevard ("What was wrong with just plain Eighth Avenue?" Lucas grouses), Frank, once by his own description "six-feet two-inches tall, a handsome fashion plate, rough and ready, slick and something to see" but now teetering around "like a fucking one-legged tripod" due to a cartilage-less, arthritic knee, is no more noticeable than he was all those years ago, when he peered through Nellybelle's window.

Indeed, just from looking, few passersby might guess that Frank, according to his own exceedingly ad hoc records, once had "at least fifty-six million dollars," most of it kept in Cayman Island banks. Added to this is "maybe a thousand keys of dope" with an easily realized retail profit of no less than three hundred thousand dollars per kilo. His real estate holdings included "two twenty-plus-story buildings in Detroit, garden apartments in Los Angeles and Miami, another apartment house in Chicago, and a mess of Puerto Rico." This is not to mention "Frank Lucas's Paradise Valley," eight hundred acres back in North Carolina on which ranged three hundred head of Black Angus cows, "the blue ribbon kind," including several "big balled" breeding bulls worth twenty-five thousand dollars each.

Nor would most imagine that the old man in the fake Timberland jacket once held at least twenty forged passports and was a prime mover in what Federal Judge Sterling Johnson, who in the 1970s served as New York's special narcotics prosecutor, calls "one of the most outrageous international dope smugglers ever … an innovative guy who broke new ground by getting his own connection outside the U.S. and then selling the stuff himself in the street … a real womb to tomb operation."

Johnson's funerary image fits well, especially in light of Lucas's most audacious, culturally pungent claim to fame, the so-called cadaver connection. Woodstockers may remember being urged by Country Joe and the Fish to sing along on the "Fixin' to Die Rag," about being the first one on your block to have your boy come home in a box. But even the most apocalyptic-minded sixties freak couldn't have guessed that the box also contained half a dozen keys of 98 percent pure heroin. Of all the dreadful iconography of Vietnam—the napalmed girl running down the road, Lieutenant Calley at My Lai, the helicopter on the embassy roof, and more—the memory of dope in the body bag, death begetting death, most hideously conveys Nam's still-spreading pestilence. The metaphor is almost too rich. In fact, to someone who got his 1-A in the mail the same day the NVA raised the Red Star over Hue, the story has always seemed a tad apocryphal.

But it is not. "We did it all right … ha, ha, ha …" Frank chortles in his mocking, dying crapshooter's scrape of a voice, recalling how he and fellow Country Boy Ike Atkinson arranged for the shipment. "Who the hell is gonna look in a dead soldier's coffin? Ha, ha, ha."

"I had so much fucking money, you have no idea," Lucas says now, his heavy-lidded light brown eyes turned to the sky in mock expectation that his vanished wealth will rain back down from the heavens. "The forfeits took it all," Frank says mournfully, referring to the forfeiture laws designed by the government under sundry RICO and "continuing criminal enterprise" acts to seize allegedly ill-gotten gains amassed by gangsters like Frank Lucas.

Some think Lucas still has a couple of million stashed somewhere, perhaps buried in the red dirt down in North Carolina. Hearing this only makes the old dealer grimace. "If they find it, I sure hope they send me some, a mil or two. Shit, I'd take a hundred dollars, 'cause right now I'm on my ass," Frank says, driving downtown on Lenox Avenue behind the wheel of my decidedly un-Superfly powder blue Toyota station wagon, the one with Milky Way wrappers and basketball trading cards on the floor. We were going to go in Frank's car, a decade-old Sedan de Ville, but it was unavailable, the transmission having blown out a few days earlier. "Mother-fucker won't pull, gonna cost twelve hundred bucks, that a bitch or what?" Lucas had moaned into his cell phone, calling from the rainy roadside where a tow truck was in the process of jacking up his bestilled Caddy.

An informative if wary guide, Lucas, who said he hadn't been to Harlem in "five, six years," found the place totally changed. Aside from the hulking, cavernous 1365th Infantry Armory, where Lucas and his Country Boys used to unload furs and foodstuffs from the trucks they'd hijack out on Route 9, nothing looked the same. Still, almost nearly every block, every corner, summoned a memory. Over on Eighth Avenue and 127th Street, up above the rim and tire place, used to be Spanish Raymond Marquez's number bank, the biggest in town. On one Lenox Avenue corner is where "Preacher got killed," on the next is where Black Joe bought it. Some deserved killing, some maybe not, but they were all dead just the same.

In front of a ramshackle blue frame house on West 123rd Street, right next to where the two-eight precinct used to be, Lucas stops and gets nostalgic. "I had my best cutters in there," he says, describing how his "table workers," ten to twelve women wearing surgical masks, would "whack up" the dope, cutting it with "60 percent mannite." The ruby-haired Red Top was in charge. "I'd bring in three, four keys, open it up on the table, let Red go do her thing. She'd mix up that dope like a rabbit in a hat, never drop a speck, get it out on the street in time.… Red … I wonder if she's still living.…"

At 135th Street and Seventh Avenue, Lucas stops again. Small's Paradise used to be there. Back in the Day, there were plenty of places, Mr. B's, Willie Abraham's Gold Lounge, the Shalimar if you were hungry, the Lenox Lounge, a nice place to take your girl. But Small's, then run by Frank's friend, Pete McDougal, was the coolest. "Everyone came by Small's … the jazz guys, politicians. Ray Robinson. Wilt Chamberlain when he bought a piece of the place and called it Big Wilt's Small's Paradise … At Small's, Frank often met up with his great friend, the heavyweight champ Joe Louis, who would later appear nearly every day at Lucas's various trials, expressing outrage that the State was harassing "this beautiful man." When Louis died, Lucas, who says he once paid off a fifty-thousand-dollar tax lien for the champ, was heard weeping into a telephone, "My Daddy … he's dead." It was also at Small's, on a cold winter's night in the late 1950s, that Frank Lucas, haint of Harlem, would encounter Howard Hughes. "He was right there, at the bar, with Ava Gardner … Howard Hughes, richest mother fucker in the world, the original ghost—that impressed me."

In the end, the little tour comes back to 116th Street. When he "owned" this street, Frank says, "you'd see a hundred junkies, lined up, sitting there, sucking their own dicks.… That's what you called it, sucking their own dicks … their heads on their laps, down in the crotch, like they was dead. People saw that, then everyone knew that shit was good."

Now, like everywhere else, 116th Street is another place. Only a few days before, the New York Times had a piece saying that Frank's old turf was a key cog in the current real estate boom characterized as "a new Harlem renaissance." An Australian graphic designer just purchased a steal of a brownstone for $237,000, the Times reported, cheering that whole area "once destroyed by drugs, crime, and debilitation … [an area which is] on the way up." This news does not please Lucas. He and his Country Brother Shorty used to own property in the area, so that's just more millions out the window.

"Uh oh, here come the gangstas," Lucas shouts in mock fright, as he regards a trio of youths, blue kerchiefs knotted around their heads, standing by a car, blaring rap music. Partial to James Brown, and "soulmen I knew like Chuck Jackson and Dennis Edwards," Frank says he is no fan of "any Wu-Tang this and Tu Pac that." One of his sons tried rapping, made a couple of records, but it was "that same ba-ba-ba … it don't do nothing for me." Once the possessor of a closetful of tailor-made Hong Kong suits, seventy-five pairs of shoes, and underwear from Sulka, Frank doesn't care much for the current O. G. styles, either. "Baggy pants prison bullshit," is his blanket comment on the Tommy Hilfiger thuglife knockoffs currently in homeboy favor.

"Well, I guess every idiot gets to be young once," Lucas snaps as he starts the car, driving half a block before slamming on the brakes.

"Here's something you ought to see," the old gangster says, pointing toward the curbside between the Canaan Baptist Church and the House of Fish. "There's where I killed that boy … Tango," Frank shouts, his large, squarish jaw lanterning forward, eyes slitting. "I told you about that, didn't I? …"

Of course he had, only days before, in distressing specific, hair-raising detail.

For Frank, the incident, which occurred "at four o'clock in the afternoon" sometime in "the summer of 1965 or '66," was strategy. Strictly business. Because, as Lucas recalls, "When you're in the kind of work I was in, you've got to be for real. When you say something, you've got to make sure people listen. You've got to show what exactly you're willing to do to get what you want.

"Everyone, Goldfinger Terrell, Hollywood Harold, Robert Paul, J.C., Willie Abraham, they was talking about this big guy, this Tango. About six-foot-five, 270 pounds, quick as a cat on his feet.… He killed two or three guys with his hands. Nasty, dangerous mother. Had this big bald head, like Mr. Clean. Wore those Mafia undershirts. Everyone was scared of him. So I figured, Tango, you're my man.

"I went up to him, just talking, I asked him if he wanted to do some business. He said yes. I gave him five thousand dollars, some shit money like that.… Because I know he was gonna fuck up. I knew he wouldn't do what he said he would and he was never, ever, going to give me my money back. That's the kind of guy he was. Two weeks later I'm on the block, and I go talk to him. ‘Look man,' I say, ‘you didn't do that thing, so where's my money?'

"Then, like I knew he would, he started getting hot, going into one of his real gorilla acts. He was one of them silverback gorillas, strong, like in the jungle, or on TV. A silverback gorilla, that's what he was.

"He started cursing, saying he was going to make me his bitch, stick his whatever in my ass, and he'd do the same to my mama, too. Well, as of now, he's dead. My mama is a quiet church lady and I can't have that sort of talk about her. No question, a dead man. But I let him talk. A dead man should be able to say anything he wants to. It is his right. Last will and whatever. Now there's a crowd, the whole fucking block is out there. They want to see what's gonna happen, if I'm going to pussy out, you know. He was still yelling. So I said to him, ‘When you get through, let me know.'

"Then the motherfucker knows I'm going to kill him. So he broke for me. But he was too late. I shot him. Four times, bam, bam, bam, bam.

"Yeah, it was right there," says Frank Lucas thirty-five years after the shooting, pointing out the car window to the curbside to where a man in coveralls is sweeping up in front of the Canaan Baptist Church, Wyatt Tee Walker, senior pastor.

"Right there … the boy didn't have no head in the back. The whole shit blowed out.… That was my real initiation fee into taking over completely down here. Because I killed the baddest motherfucker. Not just in Harlem, but in the world."

Then Frank laughs.

Frank's laugh: It's a trickster's sound, a jeer that cuts deep. First he rolls up his slumped shoulders and cranes back his large, angular face, which despite all the wear and tear remains strikingly handsome, even empathetic in a way you'd like to trust, but know better. Then the smooth, tawny skin over his cheekbones creases, his ashy lips spread, and his tongue snakes out of his gatewide mouth. Frank has a very long, very red tongue, which he likes to dart about like a carny's come-on for real good loving. It is only then the aural segment kicks in, staccato stabs of mirth followed by a bevy of low rumbled cackles.

Ha, ha, ha, siss, siss, siss. For how many luckless fools like Tango was this the last sound they ever heard on this earth?

Frank's laugh translates well on tape. Listening to a recording of our conversations, my wife blinked twice and leaned back in her chair. "Oh," she said, "you're doing a story on Satan.… Funny, that's exactly how I always imagined he might sound." She said it was like hearing a copy of the real interview with a vampire.

"After I killed that boy," Frank Lucas goes on, gesturing toward the corner on the other side of 116th Street, "from that day on, I could take a million dollars in any kind of bag, set it on the corner, and put my name on it. Frank Lucas. And I guarantee you, nobody would touch it. Nobody."

Then Frank laughs again. Ha … ha … ha. He puts a little extra menace into it just so you don't get too comfortable with the assumption that your traveling partner is simply a limping old guy with a gnarled left hand who is fond of telling colorful stories and wearing a five-dollar acetate shirt covered with faux-NASCAR logos.

Just so you never forget exactly who you are dealing with.

When asked about the relative morality of killing people, selling millions of dollars of dope, and playing a significant role in the destruction of the social fabric of his times, Frank Lucas bristles. What choice did he have, he demands to know. "Kind of sonofabitch I saw myself being, kind of money I wanted to make, I'd have to be on Wall Street. From the giddy-up, on Wall Street. Making a damn fortune. But I couldn't have gotten a job even being a fucking janitor on Wall Street."

Be that as it may, there is little doubt that when, on a sweltering summer's afternoon in 1946, Frank Lucas first arrived in Harlem, which he'd always been told was "nigger heaven, the promised land," his prospects in the legitimate world were limited. Not yet sixteen years old, he was already on the run. Already a gangster.

It couldn't have been any other way, Lucas insists, not after the Ku Klux Klan came to his house and killed his cousin Obedai. "Must have been 1936, because I was born September 9, 1930, and I wasn't more than six. We were living in a little place they call La Grange, North Carolina. Not even La Grange. Way in the woods. Anywise, these five white guys come up to the house one morning, big rednecks.… And they're yelling, ‘Obedai, Obedai … Obedai Jones … come out. Come out you nigger …' "They said he was looking at a white girl walking down the street. ‘Reckless eyeballing,' they call it down there.

"Obedai was like twelve or thirteen, and he come out the door, all sleepy and stuff. ‘You been looking at somebody's daughter. We're going to fix you,' they said. They took two ropes, a rope in each hand, they tied him down on the ground, facedown on the porch, and two guys took the rope and … pulled it tight in opposite directions. The other guy shoved a shotgun in Obedai's mouth and pulled the trigger simultaneous."

It was then, Lucas says, that he began his life of crime. "I was the oldest. Someone had to put food on the table. My mother was maxed out. I started stealing chickens. Knocking pigs on their head, dragging them home.… It wasn't too long that I started going over to La Grange, mugging drunks when they come out of the whorehouse. They'd spent their five or six bucks buying ass, getting head jobs, then they'd come out and I'd be waiting with a rock in my hand, a tobacco rack, anything.…

By the time he was twelve, "but big for my age," Lucas says, he was in Knoxville, Tennessee, on a chain gang, picked up by the police after breaking into a store. In Lexington, Kentucky, not yet fourteen, he lived with a lady bootlegger. In Wilson, North Carolina, he got a truck driver job at a pipe company, delivering all over the state, Greenville, Charlotte, and Raleigh. The company was owned by a white man, and Lucas started in sleeping with his daughter. This led to problems, especially after "Big Bill, a fat, 250-pound beerbelly bastard," caught them in the act. In the ensuing fight, Lucas, sure he was about to be killed, managed to hit Bill on the head with a piece of pipe, laying him out.

"They didn't owe me but a hundred dollars for the work I done, but I took four hundred and set the whole damned place on fire." After that, his mother told him he better get away and never come back. He bummed northward, stopping in Washington, which he didn't like, before coming to Harlem.

"I took the train to Thirty-fourth Street. Penn Station. I went out and asked the police how you get to Fourteenth Street, what bus you take. I had only a dollar something in my pocket. I took the bus to Fourteenth Street, got out, looked around. I went over to another policeman on the other side of the street. ‘Hey,' I said, ‘this ain't Fourteenth Street. I want to go where all the black people are at.' He said, ‘You want to go to Harlem … one hundred and fourteenth street!'

"I got to 114th Street. I had never seen so many black people in one place in all my life. It was a world of black people. And I just shouted out: ‘Hello, Harlem … hello Harlem, USA!' "

If he wanted any money, everyone told him, he better go downtown, get a job as an elevator operator. But once Frank saw guys writing policy numbers, carrying big wads, his course was set. Within a few months he was a one-man, hell-bent crime wave. He stuck up the Hollywood Bar on Lenox and 116th Street, got himself six hundred dollars. He went up to Busch Jewelers on 125th Street, told them he needed an engagement ring for his girl, stole a tray of diamonds, and broke the guard's jaw with brass knuckles on the way out. Later he ripped off a high-roller crap game at the Big Track Club on 118th Street. "They was all gangsters in there. Wynton Morris, Red Dillard, Clarence Day, Cool Breeze, maybe two or three more. I just walked in, took their money. Now they was all looking for me."

The way he was going, Frank figures, it took Bumpy Johnson, the most mythic of all Harlem gangsters (Moses Gunn played Johnson in the original Shaft, Lawrence Fishburne did it twice, in The Cotton Club and the more recent Hoodlum) to save his life.

"I was hustling up at Lump's Pool Room, on 134th Street. I got pretty good with it. Eight-ball and that. So in comes Icepick Red. Now, Icepick Red, he was a fierce killer, from the heart. Tall motherfucker, clean, with a hat. Freelanced Mafia hits. Had at least fifty kills. Anyway, he says he wants to play some pool, took out a roll of money that must have been that high. My eyes got big. I knew right then that wasn't none of his money. That was MY money … there's no way he's leaving the room with that money.

"‘Who wants to shoot pool?' Icepick Red keeps saying. ‘Who wants to fucking play?' I told him I'm playing but I only got a hundred dollars … and he's saying, what kind of sissy only got a hundred dollars? All sorts of shit. The way he was talking, I wanted to take out my gun and kill him right there, take his damn money. I just didn't care what happened.

"Except right then everything seemed to stop. The jukebox stopped, the poolballs stopped. Every fucking thing stopped. It got so quiet you could have heard a rat piss on a piece of cotton in China.

"I turned around and I saw this guy—he was like five-ten, five-eleven, dark complexion, neat, looked like he just stepped out of Vogue magazine. He had on a gray suit and a maroon tie, with a gray overcoat and a flower in the lapel. You never seen nothing that looked like him. He was another species altogether. You could tell that right away.

"‘Can you beat him?' he said to me in a deep, smooth voice.

"I said, ‘I can shoot pool with anybody, mister. I can beat anybody.'

"Icepick Red, suddenly he's nervous. Scared. ‘Bumpy!' he shouts out, ‘I don't got no bet with you!'

"But Bumpy ignores that. ‘Rack 'em up, Lump!'

"We rolled for the break, and I got it. And I wasted him. Just wasted him. Icepick Red never got a goddamn shot. Bumpy sat there, watching. Didn't say a word. But when the game's over, he says to me, ‘Come on, let's go.' And I'm thinking, who the fuck is this Bumpy? But something told me I better keep my damn mouth shut. So I got in the car. A long Caddy I think it was. First we stopped at a clothing store; he picked out a bunch of stuff for me. Suits, ties, slacks. Nice stuff. A full wardrobe. Bumpy never gave the store guy any money, just told them to send it up to the house. Then we drove to where he was living, on Mount Morris Park. He took me into his front room, said I should clean myself up, sleep there that night.

"I wound up sleeping there for about six months after that.… You see, Bumpy had been tracking me. He figured he could do something with me, I guess. After that night, things were different. All of a sudden the gangsters stopped fucking with me. The cops stopped fucking with me. I walk into the Busch Jewelers, look right at the man I robbed, and all he says is: ‘Hello, can I help you, sir?' Because now I'm with Bumpy Johnson—a Bumpy Johnson man. I'm seventeen years old and I'm Mister Lucas.

"Bumpy was a gentleman among gentlemen, a king among kings, a killer among killers, a whole book and Bible by himself," notes the still-reverent Lucas. "He showed me the ropes—how to collect, how to figure the vig. Back then, everybody, every store, business, landlord above 110th Street, river to river, had to pay Bumpy. It was the Golden Rule: You either paid Bumpy or you died. Extortion, I guess you could call it. Everyone paid except the mom-and-pop stores, they got away for free.…"

After a while, Frank moved up. Three or four days a week he'd drive Johnson downtown, to the Fifty-seventh Street Diner across from Carnegie Hall, and wait outside while the boss ate breakfast with Mafia stalwart Frank Costello. On another occasion, around 1950, Bumpy told him to pack his bag, they were taking a trip. "We're on the plane, he says we're going to see Charley Lucky in Cuba. Imagine that! A Country Boy like me, going to visit Lucky Luciano!" reports Lucas, who spent his time guarding the door, "just one more guy with a bulge in his pocket."

"There was a lot about Bumpy I didn't understand, a lot I still don't understand," Frank reflects. "When he was older he'd be leaning over his chess-board up there at the Lenox Terrace, with these Shakespeare books around, listening to soft piano music, Beethoven—or that Henry Mancini record he played over and over, ‘Elephant Walk.' Then he'd start talking about philosophy, read me a passage from Tom Paine, the Rights of Man.… What do you think of that, Frank, he'd ask … and I'd shrug, because I wouldn't know what to say. What could I say? What did I know? About the only book I remember reading was Harold Robbins's The Carpetbaggers."

In the end, as Frank tells it, Bumpy died in his arms. "We was eating at Wells Restaurant on Lenox Avenue, talking about day-to-day stuff. Chitchat. I think Billy Daniels, the singer, might have been there. Maybe Cockeye Johnny, JJ, or Chickenfoot. When Bumpy was around, there was always a crowd, people wanting to talk to him. All of a sudden Bumpy started shaking and he fell over, right up against me. Never said another word."

Two months after Martin Luther King's assassination, the headline of the front-page account of Bumpy Johnson's funeral in the Amsterdam News headline read, BUMPY'S DEATH MARKS END OF AN ERA. Bumpy had been the link back to the wild days of Harlem gangsterism, to people like Madame St. Clair, the French-speaking Queen of Policy, and the wizardly rackets magnate Casper Holstein, who reportedly aided the careers of Harlem Renaissance writers like Claude McKay. Also passing from the scene were characters like Helen Lawrenson, former managing editor of Vanity Fair (and mother of Joanna Lawrenson, who would marry Abbie Hoffman), whose tart, engrossing account of her concurrent affairs with Condé Nast, Bernard Baruch, and Ellsworth "Bumpy" Johnson can be found in the long-out-of-print Stranger at the Party.

Lucas says, "There wasn't gonna be no next Bumpy. You see, Bumpy, he believed in that ‘share the fortune' thing. Spread the wealth. I was a different sonofabitch. I wanted all the money for myself.… Besides, I didn't want to stay in Harlem. That same routine. Numbers, protection, those little pieces of paper flying out of your pocket. I wanted adventure. I wanted to see the world."

A few days after our Harlem trip, watching a Japanese guy in a chef hat dice up some hibachi steak in a fake Benihana place beside an interstate off-ramp, Frank told me how he came upon what he refers to as his "bold new plan" to smuggle thousands of pounds of heroin from Southeast Asia to Harlem. It is a thought process Lucas says he often uses when on the verge of "a pattern change."

First he locks himself in a room, preferably a hotel room on the beach in Puerto Rico, shuts off the phone, pulls down the blinds, unplugs the TV, has his meals delivered outside the door at prearranged times, and does not speak to a soul for a couple of weeks. In this meditative isolation, Lucas engages in what he calls "backward tracking … I think about everything that has happened in the past five years, every little thing, every nook and cranny, down to the smallest detail of what I put on my toast in the morning."

Having vetted the past, Lucas begins to "forward look … peering around every bend in the road ahead." It is only then, Frank says, "when you can see all the way back to Alaska and ahead as far as South America … and decide that nothing, not even the smallest hair on a cockroach's dick, can stand in your way"—that you are ready to make your next big move.

If he really wanted to become "white boy rich, Donald Trump rich," Lucas decided he'd have to "cut the guineas out from above 110th Street." He'd learned as much over the years, running errands for Bumpy over to Pleasant Avenue, the East Harlem mob enclave, where he'd pick up "packages" from Fat Tony Salerno's guys, men with names like Joey Farts and Kid Blast. "I needed my own supply. That's when I decided to go to Southeast Asia. Because the war was already on and people were talking about a lot of GIs getting strung out over there. So I knew if the shit is good enough to string out GIs, then I can make myself a killing."

Lucas had never been to Southeast Asia, but felt confident. "It didn't matter about it being foreign," Frank says, "because I knew it was a street thing over there. You see, maybe I went to school only three days in my life, but I got a Ph.D. in street. I am a doctorate of street. When it comes to a street atmosphere, I know what I'm doing. I know I'm going to make out."

Once in town, Frank checked into the swank Dusit Thani Hotel, where he often spent afternoons watching coverage of the war being waged a couple of hundred miles to the east. Lucas soon hailed a motorcycle taxi to take him to Jack's American Star Bar, on the edge of the then-notorious Patpong sex district. Offering hamhocks and collard greens on the first floor and a wide array of hookers and dope connections on the second, the Soul Bar, as Frank calls it, was run by the former U.S. Army master sergeant Leslie (Ike) Atkinson, a Country Boy from Goldsboro, North Carolina, which made him as good as family.

"Ike knew everyone over there, every black guy in the army, from the cooks on up," Frank says. "A lot of these guys, they weren't too happy to be over there, you know. That made them up for business.…" It was what Frank calls "this army inside the army, that was our distribution system." According to Lucas, most of the shipments came back on military planes routed to eastern seaboard bases like Fort Bragg, and Fort Gordon in Georgia, places within easy driving distance of his Carolina ranch. Most of Frank's "couriers" were enlisted men, often cooks or plane maintainance men. But "a lot of officers were in there, too. Big ones, generals and colonels, with eagles and chickens on their collars. These were some of the greediest motherfuckers I ever dealt with. They'd be getting people's asses shot up in battle, but they'd do anything if you gave them enough money."