8,63 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Seren

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

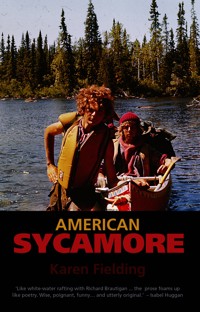

The lives of congenial American fly-fisherman Billy and his younger sister Alice meander alongside the Susquehanna River in this offbeat coming-of-age novel of death, madness, and fishing by debut author Karen Fielding. What starts out as a frolic of losers and drifters along the American riverscape flows into something more sinister when twelve-year-old Billy Sycamore encounters a stranger in the woods, while Alice is left to deal with the fall-out. In the spirit of Richard Brautigan's Trout Fishing in America and idiosyncratic like a George Saunders story, American Sycamore is a funny and fractious narrative about growing up in a small town in northeast America, with not a lot to do, but a whole lot to worry about.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 240

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2014

Ähnliche

Contents

Title Page

Dedication 1

All this happened, more or less

Dedication 2

PART I - NORTH OF THE MASON DIXON LINE

ABOUT BEFORE

MRS SPRAGUE

THE REAL PEOPLE

YELLOW BREECHES CREEK

AMERICAN ANGLER

HOW TO COOK A RACCOON

GENERAL LEE

THE SEVENTH STREET BILLIARD HALL

DICK’S WORLD OF POWER TOOLS

BUFFALO HOOF

OPAL’S HOUSE

GLONELL

CANTON STREET

FIREWATER

MARIANNE MOORE

THE STANLEYS

THE GENERAL

HOG-TIED

SITUATION ETHICS

THE ROOT LADY

THE BOY SCOUTS OF AMERICA

THROWING BEER CANS AT THE LOCAL WILDLIFE

THE OLD METAL BRIDGE

GRAVE ROBBERS

BLUE EYE CREEK

THE ROAD TO CRAZY

THE BIG LEAP

PROLOGUE TO SALT LICK CREEK

SALT LICK CREEK

MALL OF AMERICA

WHEN THE INDIANS OWNED THE BINGO HALL

HEY, BROTHER

A BEWILDERING NET

BILLY’S GIRLFRIEND

THE FISH IN THE WOODS THAT WALKED TO THE RIVER

DELMAN’S CREEK

EARTH BATTERIES

SCHLENK AUTO

ROLA COLA

ALL IN THE MIND

THE PSYCHIATRIC WARD

HISTORICAL BATTLES

FOUL SHOT

MRS BILLY SYCAMORE

THE ENCYCLOPEDIA OF BASKETBALL

AMERICAN OPTIMISM

PART II - SOUTH OF THE MASON DIXON LINE

GONE FISHING

THE TRIPLE D TRAILER COURT

FUNNY LOOKING FIDDLER CRABS

A GLIMPSE OF SOMETHING FAR BIGGER (PART ONE)

A GLIMPSE OF SOMETHING FAR BIGGER (PART TWO)

OLD SPARKY

SUMMER RAIN

HEART AND BONES

THE BIG HOUSE

PART III – THE DELUGE

THE UPSIDE OF MANIA

THE DOWNSIDE OF MANIA

ALL KINDS OF MANIACS

HALFWAY BETWEEN THIS WORLD AND THE NEXT

AN UNREPENTANT DEVIANT

THE DEATH OF MRS SPRAGUE

CROWNED NIGHT HERONS

THE POLICE

(SOMEWHERE) DOWN THE CRAZY RIVER

ALICE MEETS THE INDIAN

THE LAST GARAGE SALE

Notes

Acknowledgements

Copyright

AMERICAN SYCAMORE

Karen Fielding

To Fran, Annie and Jacob

All this happened, more or less.

Slaughterhouse5, Kurt Vonnegut

For my brother

PART I -

NORTH OF THE MASON DIXON LINE

ABOUT BEFORE

I have yet to see a bear walk in the woods. I have not seen anyone struck by lightning or drown in the river. But these things happen. They always do and they always will and Billy Sycamore, two years older, two foot taller, and too good a fisherman to notice much, got a little funny. Sometimes people ask if I have a brother. This is a perfectly normal question. I’m just not sure how to reply.

The great cities of the world built themselves upon the great rivers of the world. People need the rivers, not vice versa. People forget that. Some rivers start from snows high up or springs underground. Some crisscross each other; some roar along steady and strong. Some disappear.

People used to think the Susquehanna River, like all great rivers encircling the globe, magically flowed from the middle of the earth. That’s what people thought when the world was still flat.

Lately I have been thinking about my own beginnings along the Susquehanna River with its hundreds of rivulets and tributaries converging.

I am lonely for this river.

The home with black shutters and large-winged crows. The red geraniums in summer and horse chestnuts in the fall. The abandoned old house by the creek.

The fish in the woods that walked to the river.

The Indian who flew away like a bird.

MRS SPRAGUE

When the river rose and flooded our town the wind blew the geography teacher’s roof off. She lived in a tin-clad house close to the Susquehanna River. There were lightning rods jutting from the roof in various angles and directions, much like the hair that sprung out from Mrs Sprague’s head. In 1972 Mrs Sprague wore cat-shaped eyeglasses and she hated the North Vietnamese. She despised them in the same way a preacher hates the Devil. On the other hand, she seemed to like Richard Nixon and Germany was pretty high on her list too. She made us learn the days of the week in German. She made us count to twenty in German. Then she’d tell us the North Vietnamese were going into South Vietnam to kill all those poor people. She made it sound pretty dire, Mrs Sprague. Then she’d have us write on a piece of paper if we were for the North Vietnamese or the South Vietnamese. After a manipulative speech like that, who in their right mind is going to write down ‘North Vietnamese’ unless their parents made their own peanut butter or grew pot in their backyard. Nobody in our seventh-grade class had any more enlightened parental types than we had – upper middle class drunks who voted for Richard Nixon, twice.

I remember glancing up from my desk to see her unfold each piece of paper and nod her head with the satisfaction of a mongoose. And I remember when she asked if Billy Sycamore was my brother. ‘Are you related?’

‘He’s my brother,’ I said.

‘Well that’s very odd,’ she said. ‘When I asked if you were his sister he said: “Mrs Sprague, we aren’t related at all.”’

THE REAL PEOPLE

Along the banks of the Susquehanna River the ancient bones of Indian chiefs were buried with strings of beads, a couple of spears, and a few clay pots.

Each year we had a spring thaw. If it melted too much snow on the Blue Ridge Mountains, it churned up the banks and shifted the bones of the Indians, while the floodwater trapped whitetail deer and black bears on chunks of ice in the fast-flowing river.

For some time, the bears had been lumbering into town, across the Lincoln Avenue Bridge, along Union Street, and into the yards of the houses higher on the hilltop looking for food for themselves and their cubs. A black bear standing seven foot tall broke into a house. It tore a hole right through the wire mesh of the screened-in porch. It had smelled peanut butter cookies cooling on a tray. The bear sat down on an Oriental rug and ate all two dozen cookies. Then it did a crap in the middle of the rug and went home.

They say our great great grandfather ran like hell when he saw a black bear. He migrated to North America from Wales in 1760 and he arrived with a cane fishing rod and hand-tied flies. He drank too much, and he spoke Welsh when he drank too much, telling anyone who would listen that the Spanish were not the first explorers to set foot in the new world, it was the Welsh.

He fished the streams feeding the Susquehanna River flowing east, to the sea, those tributaries on the western side running downstream. He spent his whole lifetime on the river. He met the Iroquois people there. He spoke to them in Welsh and they gave him chewing gum. Star-shaped leaves, winged twigs and spiny seed balls. Sweet gum sap.

The Iroquois people must have liked our great great grandfather. They didn’t scalp him.

They might have said: ‘See this stream? One day it won’t meander through the mayflower and dogwood and pine. It’s going to shift and the water won’t act right anymore. It will be put upon. When things are put upon, they don’t act right.’

YELLOW BREECHES CREEK

Billy Sycamore wore a vest with twenty-seven pockets. It was regulation khaki and he kept all sorts of things in there: a can of Pepsi, a .38 caliber pistol, his math homework. He had saved up a lot of birthday money to buy the gun.

The Terry twins, identical fair-haired sisters who would grow into the well-earned titles ‘Herpes I’ and ‘Herpes II’, liked to hang out by the river. They tried to seem adept at bait and tackle. They tried to seem knowledgeable about the fathead minnow and the rainbow smelt. They did all of this fishing fabrication to impress Billy because Billy was most handsome: eyes the colour of river algae, and black lashes like the long, evening shadows in a mountain stream. His dusky blond hair grew into a wild curly haze. He had a smile that was infectious but uneven; when he turned fourteen he removed his braces with a wrench.

On his fifteenth birthday the twins gave Billy a lighter. Well-polished brass with a flintlock and tiny wheel. Billy said they shoplifted it.

Billy liked the sisters and he liked the lighter. He said he’d keep it in one of his pockets should he ever have to face a firing squad.

There are no firing squads in south central Pennsylvania, so Billy and I used the lighter to set off firecrackers in the field behind our house instead. A great whirl of flame, wheat, and scorched summer grass rose into the sky. The blowback caught the edge of his T-shirt forcing him to the ground to roll over the crickets and grasshoppers and wild strawberries beneath him. But he liked to spend the majority of his time fishing. Not because the twins sat either side of him – mostly without their clothes on – but because the waist-deep waters of Yellow Breeches Creek and the cool, fast-flowing current tugged at his heart and fishing line.

Billy stood barefoot in the cold mountain stream. He’d dead-drift a white belly sculpin or dry-fly fish using woolly buggers. Now and then he used Wonder bread and Velveeta cheese. He did a lot of dry-fly fishing in late summer when the trout feed on the surface of the creek. He fished the upper end of the creek where the stream narrowed to twenty feet in places, until the river changed again. When it flowed eastward it widened and took a shot of cold water from Boiling Springs Lake.

Sometimes his friend Juan Goldstein came along. The Ludwig Wittgenstein of our little town, Juan could relate to Billy in parallelograms. His IQ was way up there. He was also a philosopher. When Juan’s grandparents died during an earthquake in Mexico City (a building fell on them) he said, ‘Ah, yes. But they were old.’

Billy held the unwavering respect of Juan, for his original way of seeing reality and for never failing to have, on hand, a reliable source of inspiration and justification.

Nuestra vidas son los rios

Que van a dar en el mar

He started thinking laterally, Billy, which is not a good thing for somebody who walks into a room and says, ‘I’m going to kill myself today, and what are you doing?’

que es el morir…1

Try as I might, I could not see the connection between butane and one’s own soul except when Billy and Juan tried to set my hair on fire.

which is death…

Billy rowed along the ever-drifting memory bank of his mind. He tried to forget and he tried to remember. He ran his fingers along the edges of life: leaves toothed and lobed, or arranged feather-like; needle-like. He seemed clear-eyed, truer to the curve of his own life with a fishing rod than at any other time, unaware of what was going to come his way.

AMERICAN ANGLER

Everything affects me. Everything affected Billy too.

We come from a long line of affected people.

Our Great Aunt Belle thought she was a lumberjack. She walked the streets of a little coalmining town in northeast Pennsylvania in the deep snows at Christmas, carrying an axe and sizing up trees. Then she’d wander down to the railroad tracks, drink whisky with the dirty old men she let fondle her breasts. Our mother’s family made money in hotels along the Susquehanna River, then in soda pop. Then they had Aunt Belle’s frontal lobe removed.

Some said Billy was beautiful but wild like a river when it floods its banks. ‘He’s like Aunt Belle,’ they’d whisper. Aunt Belle had the lobotomy; nobody wanted to be like her. ‘I think he takes after Great Aunt Elvira,’ said somebody else. Great Aunt Elvira wore men’s clothes and she could do five different types of dog barks. Nobody wanted to be like her.

Billy said the Sycamore was the tree whose leaf most closely resembled the human heart. For his eighth birthday our father offered him a heart: a human heart made out of plastic. It had ventricles, four chambers, and blue-and-red-coloured veins. Our father hoped Billy would become a doctor like both he and his father before him. He wanted Billy to have direction. The heart sat on his dresser until he turned twelve, got a BB gun and blew a hole through it.

Billy’s own heart took shape in the mountains. On a freezing nightin a tent pitched beneath a black sky filled with silver stars, when our parents ran off and married.

Sometimes I tried to picture my mother, an eighteen year old, dark hair streaming down and her shoes crushing the tightly curled heads of ferns; a wind blowing across her mouth like sails on a ship carrying strangers to distant places; but she was anchored here, where the stillness and fury had astonished her: flame-rose cheeks and lilac-blue eyes, hands to thighs, mud-caked conscience. She said she could smell the sea and taste the salt on her tongue. But this was the river, where filtered light bathes tree roots, touches the earth…it was mid-winter after all; the earth was rain-soaked and snowy, full of decaying leaves.

When Billy turned nine our father gave him a chemistry set. Billy mixed water, ethanol and Red Dye Number 2, and convinced me it was an alchemical recipe for grape juice. I took a sip then blacked out for forty-five minutes. It was pretty obvious to me he was about as medically inclined as our dog, Marvin.

But still what Billy loved most was fishing. His heart and chemical make-up belonged to the river, the current, and flow; the behaviour of fish; and technically he excelled at fly-casting and fly-fishing knots. He had subscriptions toFly, Rod, & Reel,Field & Stream,American Angler,The Fish Sniffer,andBoating World.

In his tackle box he kept all his hooks and flies. His whole world was chaos except when you opened up his tackle box. I used to slip into his bedroom just to have a look around and fiddle inside the box with its three retractable tiers, shiny lures, and plastic beads with painted eyes and wearing tiny grass skirts. He organised his lead weights, metal hooks, and rolls of tackle in various stages of exactitude.

He talked a lot about his fishing adventures, but he rarely took me. He talked about the cold, clear streams and creeks that overflowed when it rained too hard.

He talked about pike, pickerel, trout, and bass, like they were beautiful flowers in bloom. He became knowledgeable about the secret ways of minnow, grayling and trout. He understood lures, jigs, spoons and spinners better than he understood himself. He could talk about fishing until the sun set behind the Blue Ridge Mountains, and the fish sank into the darkness of the water below him; and he’d continue to cast and re-cast his line until the stars rose between his outstretched arms.

Billy Sycamore may have sat perplexed in a world of possibility but it had nothing to do with his birth or bloodline. I maintain it had everything to do with what occurred a few months before his thirteenth birthday – one March afternoon when he’d gone down to the river to go fishing – when the heavy spring-time rains drove the trout crazy and pushed them out of their winter hidey-holes. He burst through the door at home dripping with agitation and river mud. Stinking of gunpowder, scratched up and blood dried, he fled down to the basement and refused to come up. Our parents figured this was normal adolescent behaviour: sulky and withdrawn. We nearly collided in front of the basement stairs.

‘What’s wrong with you?’ I asked. He looked breathless and wild-eyed like Marvin the dog after chasing a cat down Canton Street. I searched for traces of foam at the corners of my brother’s mouth.

‘Nothing. What’s wrong withyou?’

Billy’s usual reply. He turned everything around to get around everything.

He also started to read the thesaurus for amusement. He’d say things like: ‘I’m feeling hyperborean’when he meant ‘distant’, or ‘hypothetical’when he caught a cold. He began to think about everything more and mostly in the wrong direction. He seemed put upon. Like a stream that didn’t meander right.

HOW TO COOK A RACCOON

Union Street is a two-lane road that runs mostly downstream with the current of the river. It can also run upstream all the way past Thurmont. On this route is the Indian Trading Post. The Indian Trading Post sold handmade maple-walnut candy and books on how to cook a raccoon. Billy liked the Indian Trading Post. He liked to read the pamphlets on how not to get struck by lightning (take your golf shoes off first,thenrun) and how to avoid an angry bear (play dead,thenrun).

One fine July afternoon, before Billy began glancing behind him or around the next corner – he’d go down to the Indian Trading Post to read-up on death-by-black eastern bear. He’d traipse through the cool and leafy back woods shortcut leading down to the river then halt abruptly on a lengthy stretch of asphalt.

‘What’s wrong?’ I asked. Sometimes he let me tag along. Today was one of those days.

‘I don’t feel like walking anymore,’ he said.

As children we were told to run away if a car stopped and the driver asked for directions, and never to accept candy from a stranger; we weren’t even allowed to take a ride from people we knew.

‘What if it’s Mrs Kelman?’ we asked. Mrs Kelman was about ninety years old and lived behind us in a stone house with a Great Dane. The Great Dane and I will become acquainted so well the police will have to shoot it.

‘Nobody,’ said our mother. And she made us swear up and down to high holy heaven we would never hitchhike.

Our town, like a lot of towns everywhere, attracted all kinds. John the Baptist appeared to a man and his wife ten miles upstream and told them the Susquehanna River was good for washing away sins. Geronimo rode a horse down Union Street on his way to Washington DC to meet Teddy Roosevelt and the President of Swingers of America managed Buzzy’s Italian next to the bank on Stevenson Avenue.

We have UFOs. They are hiding-out in the abandoned coal shafts in the western part of the state zipping in and out of the entrance at impossible angularity. During Billy’s thesaurus phase he’d refer to their manoeuvering asV-shaped obliquity.

Now we were standing in the hot July wind hitchhiking. About twenty cars had whizzed past in the last half hour when a black Studebaker came lumbering toward us like an old black bear and grumbled to a stop. A man with a bowl haircut and acne scars leaned across the seat and smiled through the window: ‘Where you goin’?’

‘The Indian Trading Post,’ said Billy.

The door nearly fell off when he kicked it open. ‘Hop in,’ he said.

Billy tried to climb into the backseat but there was no backseat to climb into.

‘Seat’s in the shop so you can squeeze in front with me,’ said the man, pitching the brown paper bag next to him onto the floor. The man shoved it aside with his foot and several empty beer cans rolled out. ‘Now there’s room,’ he said.

Billy started to get in when the man stopped him – ‘stick her in the middle.’

I didn’t want to get in the man’s car.

‘She gets car sick,’ said Billy. ‘She has to sit next to a window.’

‘Aw, she won’t git car sick,’ said the man. ‘I ain’t driving you to Maine.’

We weren’t even allowed to keep the apples that people handed-out for Halloween. Even the judge up the street wasn’t exempt in case this year he happened to slide razor blades in the apples like good sociopaths do every Halloween in America.

We’d all seen the instructional film. Mandatory viewing from the fourth grade on – where a stranger tells a little girl he’s got some candy in his car.

‘I’ve got some candy in my car. You like candy?’

‘Sure I do,’ says the little girl.

Of course the last scene is her lone sneaker floating down a creek somewhere in the woods, anywhere and everywhere. It’s pretty obvious the pervert did something sick and unforgiving to the child.

The man is staring at me. ‘Hey, tutti frutti,’ he asks with a derisive little smirk – ‘you like candy?’ The question turned out to be exceptionally motivational because I sprinted all the way to Union Street and Saint Claire Avenue. I didn’t want to get chopped up and buried in bits and pieces in the woods like that hunter from West Pittston last autumn whose heart was roasted over a fire by an escapee from the State Hospital. Or left rotting under a snowdrift like that poor woman a few winters back whose skeleton was discovered in the quietly melting heap with an eight-month-old skeleton baby inside her ribcage. Both stabbed by some maniac with a screwdriver.

By dinnertime Billy turned up with a Hershey Bar.

‘He really did have candy,’ said Billy.

So it seemed just plain hypocritical one afternoon as a seven-year old, sitting at Woolworths luncheon counter that the man occupying the stool next to me, a fat slob in a boiler suit, was allowed to pat my pigtails. ‘Ain’t you the cutest little pie? Ain’t you got a smile for Ole Dickie?’

I did not have a smile for old Dickie. I had nothing but a bad feeling in my whole circulatory system for Dickie. I knew nothing could happen, though, because on the other side of me sat my mother. However, I also knew her presence did not guarantee a thing as four years earlier she stood with me at the bottom of the Kelman’s driveway, chatting away to Mrs Kelman about this and about that when the Kelman’s Great Dane mistook me for a muskrat and tore half my face off. Both women managed to yank the dog off, however neither was sure I still had my right eye anymore. I knew when I saw that dog thundering down the driveway it was gunning for me, as sure as I knew Ole Dickie wanted to do unthinkable things to me now.

I looked at my mother who was looking at herself in a beautifully wrought sterling silver hand-held mirror she’d fished out of her camel-leather handbag. She pushed her eyebrows up with her pinkie finger. She pulled down at her dark, teased hair. She applied a brick-red lipstick from a gold metal tube.

And now, after all the warnings, set like so many mental rat traps about perverts, strangers, and the like I hear her say: ‘Go on –be mannerly.’

I thought she was well and truly crazy.

Of course her comment only encouraged the man. He started rubbing the sides of his face and the tops of his huge thighs. He was all jumpy and excited like it was Christmas time in paedophileville. He asked if I liked milkshakes. Did I play Jacks? – He bet I liked strawberry shortcake! He had a whole stack of colouring books in his truck – would I like to choose one? I looked over at my mother who was blotting her lips on a paper napkin while I was being pumped for personal details and groomed for child abduction. I stared into the stainless-steel countertop. Everything smelled of disinfectant.

The waitress stopped by. She distracted the man with the banana split he now probably regretted ordering.

But as we got up to go, he grabbed my elbow.

‘You gonna give Dickie a little kiss?’ he asked me. ‘That’d make Dickie happy ’cause Dickie been real sad lately.’ He made an exaggerated frown. He also pushed his face so close to mine I could see the chocolate syrup filling the gaps in his molars dripping onto his tongue, dark rivulets in a stream. He spat out a coin – a silver dime onto the countertop, spinning then stopping with an abrupt clatter when he smacked his hand flat on top of it.

‘For the ferryman,’ he said.

GENERAL LEE

My name is Alice Sycamore. I don’t have a nickname.

‘Hey, Alice,’ people say.

‘Hey,’ I say.

My middle name is Lee. Our father says we are related to General Robert E. Lee, which is a huge and ridiculous lie. We are about as related to Robert E. Lee as we are to a raccoon.

We live along the southeastern curve of the Susquehanna River where the Broadway Limited barrels along the old forged iron tracks between New York City and Chicago blowing anthracite into the atmosphere – a beautiful shiny lump of high-density coal discovered by a man who accidentally set fire to a mountain. There were Indian people too, and the slaves running north and Union soldiers running south, everybody coming or going, passing through, doing whatever people do in their time and place. At least I thought so then, or remember it that way. Of course memory can be subjective. Except I remember everything, even other people’s memories, in particular the ones they want to forget like when the Prom Queen told me my family was sick.

‘Your family is sick,’ she said.

The Prom Queen can go fuck herself (I mean that in the nicest way, of course) and I like to think of the Sycamores as rugged individualists: us and Theodore Roosevelt. This comparison to Teddy Roosevelt made our father as happy as a worm in a Tequila bottle.

‘You’re a rugged individualist,’ I told my father, ‘you and Theodore Roosevelt.’

‘Indeed!’ he said. ‘Let’s go pick pineapples!’

There are no pineapples in Pennsylvania, and the Prom Queen’s brother will move to Belize where he will live with a group of people who make their own peanut butter. But before this he got a pet monkey. I liked to go to their house to see the monkey. The monkey’s name was Chester and it lived in a large wire cage in the basement of their colonial white-brick home.

It was all alone down there, the monkey. It had a water pistol to play with which it had thrown to the bottom of the cage.

I read that 99.9 per cent of pet monkeys are mentally disturbed. I have met a lot of people 99.9 per cent disturbed. The monkey chirped like a sparrow. He rubbed his black hands together like a neurotic French sea captain.

After a while, as with most new and exciting things, the monkey’s novelty wore off: nobody came downstairs to visit the monkey; people stopped paying attention to it. The Prom Queen’s brother threw peanuts at it. The only friendly face was the cleaning lady. She’d scream: HELLO MONKEY, then wring out her mop.

The monkey escaped from the basement. It climbed through an open window and ran up a buttonwood also known as a plane or sycamore tree and this tree was as good and familiar as anything it may have ever swung around on in the Ecuadorian jungle. It yanked off one-inch brown pods and threw them at the sidewalk. It threw them at parked and moving cars. It hurtled them down on the small crowd gathering. One hit a man on the head; another struck a woman in her face. The monkey was the happiest it had been in its whole life until a squirrel bit its tail.