Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Valley Press

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

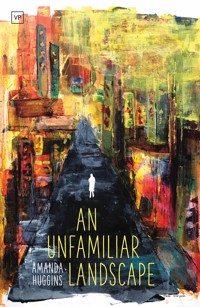

Stories from the city, the sea, the forest; stories from places where everything is not always as it first appears… From a rain-soaked Berlin to a neon-lit Tokyo, the midwest of North America to the Parisian backstreets, a suburban London kitchen to a fishing village on the Yorkshire coast, wherever these characters are travelling from or to, they are all navigating unfamiliar ground in search of answers. These are stories of yearning to belong, of the urge to escape – tales of grief and alienation, of loss and betrayal, love and hope.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 203

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

—————

An Unfamiliar Landscape

—————

Amanda Huggins

Valley Press

For everyone who has walked through the dark wood,especially those who have yet to come out the other side.

Aleksandr

I watch Alex through the kitchen window. He turns his collar up against the salt-licked wind, walks past without looking up, his wool cap pulled low.

The room is quiet and hollow now he’s gone, the mantel clock widening the emptiness as it strikes the hour. Alex said it would be fine, my mother taking the baby for a few days, he said it would do me good to have a break. But I miss the wee boy already, the straightforward way he fills each day with the mundane, the way he tangles me up in his needs, sweeps me up with his smile. He shows me the best of myself, leaves no room for the dark doubt underneath.

I say my husband’s name out loud. Aleksandr. I try to pronounce it the way his mother does, turning it over in my mouth. The sharp bite of the ‘k’ followed by the soft hiss of the ‘s’, then the sigh of the fall and the short uptick of the finish.

Aleksandr, Aleksandr, Aleksandr.

When I first met him – first craved him – I thrilled to hear his mother say it, pronouncing it in her beautiful Russian accent. The anticipation made me dizzy. I mouthed ‘Aleksandr’ at my reflection in the mirror, conscious of the way the word was formed by my lips, my tongue, my teeth. It raced down my spine in a way I knew it never would again after the first time we made love. His name was a precious gift, a gift I still hold tightly to my ribs, never daring to call him it for fear it will shatter. To everyone other than his mother he is always Alex.

I stack the bowls and plates on the shelf, turn back to the window, pause for a moment when I see him in the distance outside the herring shed. I clutch the edge of the sink until the door swings shut behind him, then I let go of my breath, watch it curl around the room like sea mist.

If Alex were to get his job back on the trawlers then perhaps he would walk tall again, north wind or no wind, no longer cowed by the weight of his needless guilt. It follows him around the house, a monkey clinging to his back, and when he leaves for work he carries it with him in his knapsack. At night it lies between us in the bed, and he turns away from it, scratches his arms as though he can feel its fingers tapping.

He says he only wants the best for me, for our baby, and I tell him we already have the best. I chose this life. I always understood it would be hard, realised that new clothes and expensive dinners would be rare. I’d seen the damp patches on the parlour walls, knew I would be dragging buckets of coal from the cellar and struggling to keep the Aga alight, that I would be fighting the rain and the wind to carry washing out to the scullery in the winter. This is exactly the life I expected when I made my choice, and it’s a good life, an honest life, a solid life.

But this morning I’m temporarily uprooted, drifting, trying to float above the high wall that bricks me in a little further every day. My comforting mantra no longer rings true; I’m unsure that anything can make Alex walk tall again.

At ten o’clock I shrug on my parka, fetch my purse, count out the last of my coins. I open the cupboards and the fridge one last time, consider what I can make with two tins of tomatoes and half a bag of potatoes, wonder if I dare ask for more credit at the village shop.

As I close the fridge door, I see a flash of crimson through the window. A stout woman clutching a beribboned box picks her way across the muddy lane, holds her coat with her free hand to avoid it snagging on the lobster pots by the gate.

I pull the door open, feel the edge catching against the swollen frame.

‘Aunt Florence, what a lovely surprise! Come in, come in, you must be frozen in that thin coat.’

I slip off my parka, pull a chair across the flags towards the Aga, throw a cushion down. I busy myself with the teapot, rinse it with hot water, spoon in the tea.

‘Stanley wanted a drive out, Yorkshire weather or not. We were feeling like two sailors with cabin fever. So I said we might as well come over to visit my lovely nephew and bring the boy’s belated christening gift.’

‘Where’s Stanley now?’

‘Oh, he decided to stay in the car. We’re parked just around the back. There’s some programme on the radio he wants to listen to. Where is my Alex today anyway?’

‘He’s doing a shift down at the herring sheds.’

‘I could pop down and see him for a moment.’

‘I don’t think you’d better. His boss is…’ I trail off, hear Florence sniff as she looks away and glances around the room, taking in the worn rag rug, the clothes drying on the rack. A large silk-covered box sits on the table between us, rain-spotted, yet unmistakably luxurious. Florence makes sure it has pride of place in the centre, pushing aside the wooden butter bowl filled with my painted eggs. Nevertheless, the eggs catch her eye and she picks one up to examine it.

‘Careful, they’re…’

Before I can finish my sentence the eggshell dents under the pressure of her thumb. She drops it quickly back into the bowl.

‘Sorry, Lindy, but how was I to know? I thought they were wood or something.’

‘It’s okay,’ I say, but we both know it isn’t.

‘Where is the boy?’ she asks, changing the subject, gesturing around the room as though she expects my baby to be hidden in one of the cupboards.

I’m still looking at the broken egg, wondering if I can repair it somehow. I press my hands to my knees beneath the check cloth, try to stop myself from reaching out for it. It’s my favourite egg, the one depicting the girl with yellow flowers in her hair and the boy with the bright blue eyes.

‘My mother has him for a few days. She’s taking him to visit my Aunt Noosh.’

‘Oh, such a shame! I wanted to see the child’s face when you open his gift. But you can look anyway.’

Florence picks up the box and hands it to me. I thank her, my heart already heavy. I can see it’s from an expensive jeweller’s in Harrogate, and I know the gift will be unsuitable, that it won’t enrich my baby’s life or fix the gable end where the rain drives through.

A gold christening bangle rests on blue velvet. I stare at it, take in the gleam and shine, but I don’t touch it.

‘It’s beautiful. Thank you so much.’

Florence reaches across, takes it from the box and holds it up to the light.

‘It’s a boy’s – look, it’s much chunkier than the ones meant for girls. Apparently they’re all the rage now. Solid gold as well. An investment.’

I hear myself swallow. ‘Thank you, Aunt Florence, I’m sure he’ll treasure it.’

‘Oh it’s nothing! Only the best for my great-nephew.’

After Florence leaves, I pick up my coat again, slip the christening bangle into the inside pocket. As I cross to the door I see Alex through the window, a tiny figure by the slipway. He picks up a wooden crate and goes back inside the shed.

There is something apologetic about the way he stands and moves, the way he hunches down as though he’s trying to take up less space in the world. I know he hates being on land, that he feels tied to the sea by an invisible thread, that it pulls him back with every ebbing tide.

I remember him telling me about the herring sheds when we first met; he was proud of his skills on the splitter, the skills his father taught him so well when he was still at school. But I know he never thought he’d have to work there.

Derek Machin came by the cottage after what happened on the trawler. I didn’t tell Alex he’d called, and he won’t be pleased if he ever finds out I begged for his job.

‘I can’t take him back on the Sally Ann, Lindy, I just can’t. He’s a danger to my crew when his anger flares up like that. The lad has no self-control. Terry would have gone overboard if it hadn’t been for Pete’s quick reaction. I might have reconsidered, but when I asked him to apologise, he refused.’

I nodded as though I understood, but I still don’t know for certain what happened out there. Did the boy who saw us in the dunes tell everyone in the village? I only found out later he was Terry’s son. Did Terry tease Alex about it until he lost his temper?

It had been as dark as sea coal that night, but when the clouds parted for a moment, a bright moon flooded the beach. I never told Alex about the boy who was watching us. When I saw his head appear over the top of the dunes I said nothing. I allowed him to watch me sitting astride Alex, my skin milk-pale in the silver light, my hair loose down my back. I performed for him, emboldened, mermaid-slick, until the clouds raced across the moon again.

In the beginning we made love wherever and whenever we wanted: in the dark woodland, cushioned by a bed of leaves; on the firm sand at the shoreline, our cries muffled by the crash of the receding waves; up on the open moorland beneath wide gold skies. We were tireless, greedy for the taste of each other. Alex picked me flowers then – anemones and primroses in the spring, wild roses in the summer. He gave me handfuls of rumbled sea glass which I still keep in a chipped glass jar on the window ledge. And when I stained my favourite grey boots with coal dust, he painted patterns on the leather to hide the marks, added birds and ribbons, hearts and anchors.

Each spring, before my birthday, Alex stole an egg from Johnny Carter’s henhouse. He crept across their yard in the early light, and I imagined the egg cupped gently in his hand, cool as stone, as he climbed back over the fence. After the first time, I told him he could take one of ours from the pantry shelf, but he said it wouldn’t truly be a gift if he did it that way. He carried the egg straight down to the boathouse, and when he’d blown it clean he painted it with the enamel paints he kept there. Every year he copied a traditional Russian design from his mother’s book: scenes of troikas and domed churches, country dachas, dashing Cossacks and rosy-cheeked girls with plaits wound around their heads. Then he placed the decorated egg in a nest of straw and left it on the bedside chair while I was still sleeping.

This year my birthday fell just after the boy was born, and for the first time there was no egg waiting for me on the chair when I woke up. Instead, there was an expensive box of violet creams from some exclusive London store, delivered at great expense.

Those early gifts, those things from the sea and the land, were – are – everything I could ever want, yet now Alex’s guilt buys me things I resent. He tells me I deserve the best, yet he can’t see he’s giving me much less. The extravagant bouquets from the florist, the handmade baby shoes, the silk slip embroidered with lilies. Yet the electricity bill is always paid on the last demand, the coal merchant threatens to refuse credit, and on the rare occasion when a bill is settled on time it’s always Alex’s slate at the Pig and Anchor.

He tells me he’ll stop drinking soon; he will, he will, he will. But he needs it now – just once a week, or maybe twice. He traces a finger down my cheek, says he can’t face the sad beauty in my face, the knowledge that he’s let me down – is letting me down – day after day. I lie and tell him he isn’t, yet my reassurances don’t sound as solid as they did before the baby came.

I pull on my old boots. The patterns Alex painted are faded and covered by new stains now, the soles starting to peel away at the toes. I step carefully around the deeper puddles, tap on Marie Merriweather’s door, look around to make sure no one is watching.

Marie’s eyes glint when she sees the bangle. ‘I can offer you a set price now, or you can leave it with me to see how much Billy can sell it for – usual terms. You takes your chance as always.’

I remember the coins in my purse, the empty cupboard, and I know there isn’t enough coal for tonight. ‘What can you offer me now?’

Marie sucks in her cheeks, pushes her glasses down her nose and pretends to examine the hallmark.

‘I have the original box back at home if you need it.’

‘£35.’

‘£45?’

‘£40 is the most I can give you now. Or you can wait, like I said.’

She reaches forward impulsively, rests her fingers on my wrist. ‘This needs to be sorted out, Lindy. You and Alex can’t go on like this, just because of what Terry’s son saw.’

So it was as I thought. I snatch my hand back and shake my head.

‘I’ll fetch the box. Don’t ever tell anyone where you got the bracelet, not even Billy. I can’t have Alex knowing I ever had it.’

I build a good fire, make a casserole, pour two glasses of cheap red wine. At ten o’clock Alex isn’t home. Sometimes he helps to mend nets and pots after his shift, or does odd jobs for Alan at the main boathouse. But he didn’t say he’d be late tonight.

I kick the coal scuttle when I realise my stupidity. It’s Friday. He’ll be in the Pig and Anchor, counting out the money he always keeps back: the odd fiver, some loose change, tucked inside the pockets of the old coat hanging on the door. And even if there is no money there, even if I’ve already taken it for groceries, he always wangles credit.

I should never have gone over to Marie’s today. Not on a Friday. Billy Merriweather is sure to be in the Anchor right now.

I can hear his voice.

‘Pay day, Alex?’

Alex will turn to see Billy at his shoulder, holding something beneath the bar, palmed in his left hand.

‘I’ve got just the thing for you,’ he’ll say softly. ‘Just the thing to make it right with the little lady when you get home after three too many. This’ll soft-soap her – something for the wee lad.’

He’ll see the glint of it as Billy lifts his arm.

‘I have the box for it too – dead smart.’

Alex will turn it around in his hand, feel the weight of it, as heavy as his heart.

‘How much?’

‘£100. It’s a bargain. £170 plus it would cost yer in the jeweller’s.’

‘I don’t get paid again until next week.’

Then he’ll think about the way my face lights up when I smile, the boy’s face as he sleeps. ‘£80? £40 next week, £40 the fortnight after that, but I get to take it home today. You know I’m good for it.’

Alex will cradle the box in both hands as he walks up to the cottage. He’ll tell himself it will make me happy and believe it to be true. Why shouldn’t we have it, he’ll ask? Only the best for our baby.

I stand up and open the door when I hear the gate creak.

‘I can’t wait to see your face when you open this box,’ he says.

‘Have you been in the Anchor?’ I ask.

‘Just for one, earlier,’ he says. ‘I’ve been doing some work in the boathouse tonight.’

‘Was Billy in the pub?’

Alex nods. ‘He gave me some good advice as it happens; a bit of a talking to if I’m honest.’ He shakes his head and smiles to himself.

I hardly listen to him. I can see it’s the same box, the slub silk still spotted with marks from the earlier rain, the ribbon now missing.

He places it on the table. ‘Go on,’ he says, smiling.

My hand shakes a little as I lift the lid. There is a nest of straw inside, dry wisps of it fall onto the check cloth. His gift sits in the centre, liquid gold in the firelight. I pick it up carefully, this thing so hopelessly weak and yet so extraordinarily strong. The detail is exquisite: a man and a woman stand in front of a small house, lamplight shining out through the windows, a baby held in the crook of the woman’s arm. The rest of the egg is washed in gold.

He laughs at the wonder in my face.

‘I’m so sorry, Lindy,’ he says. ‘For all of it. I’ll make everything right.’ He rummages in his pocket and then holds up the bangle.

‘What? I—’

‘Ssh, I’ve sorted it out, don’t worry.’

He pulls me to him and I can feel the rough callous on his right palm as he reaches for my hand, smell the salt-dark of him, a trace of woodsmoke, see the neatly stitched tear in his coat near the shoulder seam.

‘Aleksandr,’ I whisper, and I feel his name running down my spine.

The Sparrow Steps

How often did you recall that last afternoon in Haradani-en garden? I can still remember the clear blue skies, hear the leaves crackle underfoot. I held out the dry skeleton of a cherry leaf, told you autumn was proof that death could be beautiful. You took it from me, twisting the stem between your fingers.

‘So fragile,’ you said.

You lagged behind as we climbed the hill, and when we reached the top you paused, out of breath. I laughed, said we were getting older, but you didn’t reply. I think you hoped your silence would go unnoticed, yet I could hear every word you’d bitten back ringing out down the hillside and echoing around Kinkaku-ji temple.

We stopped at a bridge on the way back, and you sat on the steps to unfasten your boot, removed a small stone that was pressing into your heel. I crouched beside you, watched as you ran your fingertips over a row of bird footprints, captured forever in the newly laid concrete.

‘Proof we can sometimes leave an eternal mark, that we live on after our beautiful deaths,’ you said.

I took a photograph of the prints next to your splayed hand; the immortal footsteps of sparrows, like tiny dinosaur fossils.

‘We should make a pledge,’ I said. ‘A vow that if we ever lose touch we’ll meet here at the sparrow steps ten years from today?’

I was so sure we’d never be apart. It was an easy promise.

You looked up at the cherry trees, and for a moment I remembered them in spring: petals delicate as insect wings, fluttering down like a whisper of moths, the trees bowing with the weight of their fleeting beauty.

That’s when I saw the uncertainty in your eyes.

‘Yes,’ you said, quietly. ‘We should do that.’

Eating Unobserved

The letting agent urged Marnie to admire the handmade kitchen cabinets, to appreciate the proportions of the bedroom fireplace. But there was really no need. She’d decided to take the apartment on Rue Annette as soon as she walked into the salon, captivated by the high ceilings, the elaborate cornice, the flood of light from the huge windows. They were almost as tall as the room itself, still fitted with the original sun-faded shutters.

The concierge apologised for the furniture. He said it had been left by the previous tenant, a Madame Hubert. She’d moved abroad quite suddenly and he hadn’t had time to clear the rooms. Yet Marnie loved the worn chaise longue, the crystal chandelier in the hallway, the pale grey bedstead decorated with overblown roses. The walls were filled with foxed watercolours, pen and ink sketches of Parisian streets, portraits of forgotten ancestors. She told the concierge he could leave it all just as it was.

And in the bedroom there was a glorious oil painting, depicting a sumptuous banquet – a sensual feast of fruit, cheeses, fish and game, spilling out across a thick linen cloth. Figs were split wide open, ripe and glistening; succulent peaches wore a velvet bloom, tempting the observer to bite into their yielding flesh, to lap up the sticky spill of warm juice. Fish lay on blue platters, mouths agape, their scales glittering and slippery; rich, silky cheeses collided, their melting centres running over the edge of the board.

And when Marnie lay in bed, gazing at the painting, something inside her melted with them.

The day after she moved in, she dragged the heavy dining table across to the windows, decided she would work there in the daytime and eat her dinner there every evening. It was late autumn, too cool to eat outside on the narrow balcony, but the windows faced east, caught the sunlight during the mornings, and she could imagine how it would be in the spring. She’d buy a simple gingham cloth, enjoy breakfasts of flaky croissants and warm baguettes, brew freshly ground coffee, crowd the table with tiny dishes filled with curls of pale unsalted butter, apricot jam, fig preserve, lavender honey.

And in the evenings she might take her dinner at the small bistro on the corner. She would order simple, straightforward dishes: steak, mussels, a seasonal omelette, bread with a thick floured crust, a carafe of house wine.

But all that was for the future, when the advance came through for her next book – the novel she’d given herself six months in Paris to finish. For now she would be disciplined, work in the apartment most of the time, occasionally venturing out to cafés with her notebook, and she’d eat her dinners alone at home.

Marnie fell into an effortless routine. She bought fish and vegetables from the market each morning, bouquets of fresh herbs tied with rough twine. She wrote in the afternoons, and when the light faded she pored over the yellowed pages of the cookery books left behind by Madame Hubert, practised making bouillabaisse, croquettes and crêpes. Every evening she dressed the table as though for an opulent dinner, with candles, flowers, platters of fruit, the embroidered tablecloths and heavy silverware she discovered tucked away at the back of the kitchen press.

And when she went to bed she gazed at the painting of the banquet, half lit by the streetlamp, and in her dreams she walked into its rich dark heart, was swallowed whole by its slippery, lubricious flesh.