Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Fantasy und Science-Fiction

- Sprache: Englisch

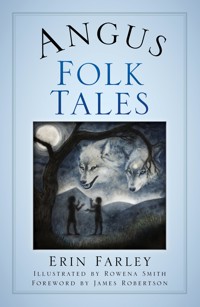

Angus is a landscape of dramatic glens and rich farmland, ancient weaving towns and fishing villages, from the city of Dundee in the lee of the Sidlaw hills in the south, and the Grampian mountains in the north. The tales of Angus are as varied as the landscapes they are tied to, told through the years in castles, bothies, tenements and Travellers' tents. Here, historical legends tell of Caterans roaming the glens, Jacobite intrigue in Glenisla and pirates roving the stormy waters off the Arbroath coast. Kelpies, broonies and fairies lurk just out of sight on riverbanks and hillsides, waiting to draw unsuspecting travellers into another world. The land bears memories of ancient battles, and ghosts continue to walk the old roads in the gloaming. In this collection, storyteller and local historian Erin Farley brings you a wealth of legends and folk tales, both familiar and surprising.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 275

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2021

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

First published 2021

The History Press

The Mill, Brimscombe Port

Stroud, Gloucestershire, GL5 2QG

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

© Erin Farley, 2021

Illustratrations © Rowena Smith

The right of Erin Farley to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without the permission in writing from the Publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 0 7509 9905 2

Typesetting and origination by Typo•glyphix, Burton-on-Trent

Printed and bound in Great Britain by TJ International Ltd

eBook converted by Geethik Technologies

CONTENTS

Foreword

Acknowledgements

Introduction

1 Legends of the Glens

2 Strathmore and the Sidlaws

3 Glamis Castle

4 Coast and River

5 The City

6 Jacobite Escapes

7 Wells and Saints

8 Stones and Souterrains

9 Hidden Treasures

10 Weel-Kent Faces and Wee Stories

Bibliography and Further Reading

FOREWORD

A landscape without names is an inhuman space. Place names can be formal – given authority by legal document, map or signpost – or informal: ‘where the burn floods’, or ‘the gate by the big oak’, or ‘where we found the injured hare’. Stories, too, can be formal or informal, written or oral. Sometimes a place gets its name from something that happened so long ago that the original event has been forgotten. Yet most inhabited places, whether farm, inn, glen, village or town, will have an ever-changing stock of stories and memories associated with them, for that is how humans make sense of the locations in which they spend their lives.

It is always worth asking what a simple, common phrase actually means. ‘Folk tales’, to me, are what ordinary people in a particular place use to mythologise both who they are and where they are, and who was there before them. We live by the facts of history and in the realities of the present, but we also need the mysteries and moral lessons that folk tales and legends give us.

I have stayed in Angus longer now than I’ve stayed anywhere else, and it informs a great deal of what I write. When I first looked into Erin Farley’s collection of rich and varied Angus tales, I had just finished writing a new novel. As I read on, I came across wolves, a banshee, a hermit, a minister with a secret life, whisky-smuggling, wild weather in the glens, and all manner of interactions – some cruel, some kindly – between the powerful and the poor of this land. What struck me was that these very elements were in my novel, yet there they had taken quite different forms. It was as if I had been at the same well from which the tales in this book are drawn, but in a different season.

Maybe that is why, when you read them, you may feel a sense of ownership not only of the stories you may already know, but also of some you don’t. And that may be because you recognise a place, or a place name, or a family name, which locates a story, however weird or scary or incredible it is, in familiar territory. This can be both unsettling and reassuring, but it is one of the things that helps to make these tales, some of which are very old indeed, belong to all the folk of Angus today, and to people further afield too. They speak of where we are, and of where we have come from. And, far into the future, people will still tell them and read them, and add tales of our times too, in order to understand who and where they are.

James Robertson

Newtyle, March 2021

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Thank you to my mother, Rowena Smith, for everything – but especially for illustrating these tales so vividly.

And thanks to her sister, my aunt Fiona Brooks, for being a witch.

Thank you to James Robertson for writing such an insightful foreword to this book. I am also grateful for support, local knowledge and helpful comments from Jim Farley, Ella Leith and Scott Gardiner at various stages of writing.

I have been lucky to be supported and encouraged by communities of excellent Scottish storytellers from all airts and pairts – thanks in particular to Tom Muir and everyone else in the Orkney Storytelling Festival team, and to the ever warm and wonderful Blether Taygether group in Dundee. And to Donald Smith, for his enthusiasm for this volume and all he does for the art of storytelling.

My biggest debt is to storytellers and collectors past and present, thanks to whom these tales have lived long enough for us to learn them. The work of James Cargill Guthrie, D.H. Edwards, Andrew Jervise, Alexander Lowson, Duncan Fraser, Betsy Whyte, Sheila Stewart, Jean Rodger, and Maurice Fleming – among many, many others – has been instrumental in continuing the Angus storytelling tradition in spoken and written form. Thank you also to staff past and present at Angus Archives, Dundee Libraries, and the School of Scottish Studies Archives, for helping to look after stories on everyone’s behalf.

INTRODUCTION

Angus (or Forfarshire, as it was officially named after the principal town until 1928) is a small county in the centre of Scotland’s east coast. On the north-west side of the county, five glens – Glenisla, Glen Prosen, Glen Clova, Glen Esk and Glen Lethnot – lead up towards the Grampian Mountains. In the middle of Angus, the rich agricultural land of Strathmore has been farmed for countless generations. In the south, across the rolling Sidlaw hills, is the city of Dundee, which grew from a tiny walled medieval town into a Victorian industrial powerhouse. Following the eastern coastline north takes you from the still-busy docks at Dundee past tiny fishing villages, dramatic sandstone cliffs and white sandy beaches, up to the port of Montrose and its wide river basin.

The folklore of Angus is shaped by landscape, people and history. Although we know little of the Pictish people themselves, the intricately carved stones and underground souterrains they left are central to Angus’s folklore, speaking to later generations of kelpies, dragons and fairy chambers. More recent history weaves in and out of legend too. The Jacobite uprisings and their aftermath affected a great many of the people of Angus, both the local nobility and the ordinary crofters in the glens, and so these too have left a strong echo in local folklore.

Gaelic was the main language of the glens, particularly the ‘top’ of the glens, until at least the late seventeenth century (and there were still native Gaelic speakers living there into the nineteenth). Some of the people in these stories – like the Glenisla hero McComie Mhor – would have spoken Gaelic as their first language. The rest of the characters here – and most of these who shared these stories around the farms and towns of Angus – would generally have spoken Scots. Although this book overall is in English, there are some things which don’t translate, and you will find some of the characters speak Scots because they quite rightly refuse to speak anything else.

Stories live alongside music, song and poetry as part of everyday culture. The hard work of agriculture was, and remains, a way of life in Angus, as was the making of cloth in the towns and cities. Many a song and story were born and sent into the world among farm workers in bothies and kitchens, or among the clack of looms in weaving sheds and jute mills. The Traveller community, who walked the straths and glens and found work at many an Angus harvest, kept song and story alive here as they did in so many parts of Scotland. The rhythms of work and the land, and the often uneasy relationship with the ‘big families’ who own it, are a constant backdrop to these tales.

A powerful sense of history, place and fate runs through the stories here, but the dramatic and supernatural are at home in the everyday, and they come with a wry sense of humour. This is a world where ministers spar with the Devil like a quarrelsome neighbour, ghosts still think about getting the neeps pulled, and the way you make porridge might be the only thing standing between you and your freedom. The folk of the farm toons of Angus, as David Kerr Cameron wrote in The Ballad and the Plough, had their dour moments but were also often ‘droll to the point of eccentricity’. This, I think, sums it up quite well.

Perhaps the best illustration of the Angus attitude to life is the story of Forfar Castle. During the Scottish Wars of Independence, Forfar was a royal seat, and of course this meant it was subject to constant attack. The castle was occupied by the English for years, until it was won back for the Scots by Robert the Bruce in 1308. Tradition says that instead of rebuilding the damaged castle, the people of Forfar dismantled its walls completely, and refused point blank to raise another one. The honour of housing royalty was hardly worth the hassle of invading soldiers getting in the way of market day.

I grew up in Edinburgh, which has plenty of its own legends, but visits to family in Angus are the setting for my earliest memories of a sense of stories. Spending holidays with my grandparents on my mum’s side in Forfar, I remember visiting Glamis Castle, looking up at the windows and wondering which one might be the secret room, spotting fairy-rings of mushrooms by Restenneth Priory, and the sheer terror that the Meffan Museum’s stories of witch-burnings instilled in me. My family on my dad’s side were in Dundee, and I have vivid memories of looking for ghosts through the windows of abandoned jute mills there after hearing they might lurk there.

I was clearly a spooky child, but I think this came from a fascination with tradition and the presence of the past rather than being morbid for its own sake. While traditional storytelling never really went away, it has certainly seen a huge revival in interest and attention in Scotland in recent years – exciting times for someone like me to live in. As I started going to storytelling sessions and events, I thought back to these legends of secret rooms and haunted mills, and particularly to the story of Jockie Barefit, which my Aunt Fiona scared me with as a child, and which remains my favourite to tell to this day. I started to wonder if perhaps I did know some stories after all, and if storytelling might be something I could do … Soon, I began seeking out more stories from these places and telling them at every opportunity, and life brought me to Dundee, where I have been lucky enough to get to know them better as part of my work in the libraries’ Local History Centre.

These stories matter. As the way we live in a landscape changes, paths to farms and wells that people walked daily threaten to fade into the hillside, and buildings are torn down and replaced. Many of these changes are very welcome – these tales leave you in no doubt that life was not easy in the past. But stories are supposed to keep going, picking up layers of meaning and carrying the experience of their tellers through the years, to tell us something about where we have come from and where we might want to go. Sometimes, they stop and rest on a page for a while. I hope that this book brings readers a new perspective on some of the places they know, and brings these stories to new voices and new ways of telling.

1

LEGENDS OFTHE GLENS

The Angus glens are a striking Highland landscape. In days past, there were small farming communities through the glens, and shepherds wandered the higher ground with their flocks. And the glens had plenty of dangers. Wolves roamed the hills, and the narrow, exposed roads brought threats from both weather and raiders. And in the dark nights, the glens were stalked by spirits tied to past sorrows. Glen Lethnot in particular was known for being a superstitious and haunted place long after the Kirk would have liked it to be.

THE TWINS OF EDZELL

In the days of King Robert the Bruce, the country of Angus was thick with forests. On the edge of one of those forests was Edzell Castle, the stronghold which guarded the foot of Glenesk. Around the castle walls, there was a small village. Among the people there was a young couple – a man who worked in the castle’s fields and his wife, a Traveller woman who had fallen in love as her family passed through the area and had settled there with him. She was a bit of a mystery to the folk there, and a lot of them believed she had some magic about her. People would sometimes ask her to tell their fortunes – who will I marry, what will the harvest be like, will my son return from his travels? She would think deeply for a while and give them answers, and the things she said usually came to pass.

The couple were expecting their first child when the man fell ill and died, and his wife had to prepare to raise her child alone. But it turned out she had not one child to raise, but two. She gave birth to twin boys, who each had a striking birthmark – one had a bright red spot on his left cheek, and the other had a similar mark on his forehead. She immediately fell in love with her two babies, and she made their living by making pegs and baskets and selling them around the houses of Edzell, and by telling the fortunes of those who asked her. But along with the admiration for her gift came a bit of suspicion. Those who did not trust her power feared it.

As the boys got older, it was clear that they were both deaf, and neither heard nor spoke. But the woman and her sons learned to sign to each other with their hands, and all was well. The twins thrived. They both grew strong and fast, and among the lads of the village they were the fastest runners, the highest jumpers, the strongest wrestlers – and they were by far the best hunters. By their teens they could hunt and fish as well as any of the laird’s men. The family home was well stocked with trout from the river, and they could always get meat from deer or even the wild boars which roamed the forest, for they could trap even these ferocious animals. There were rumours that they had even brought home the skins of wolves to warm themselves in winter.

The other young men of Edzell began to shun the twins. They were jealous of their skills, and it turned into hatred. They were also a little bit more afraid of their mother’s powers than they would admit. But the two of them were happy enough in each other’s company. Their mother worried, though, that they would one day face worse than loneliness because of who they were. She knew what it was like to feel everyone look at her as she passed through the village, and she feared that her sons, being deaf, would suffer even more for their difference. She thought it was best if people feared her and her sons, because there was at least power in that. So she laughed to herself when she heard folk talk about the magic powers her family was supposed to have, and she said nothing to put their minds at rest. Even Sir Crawford of Edzell Castle was wary of them. Sometimes he would give the family a little money, saying it was because he was sorry for their father’s death, but really, he wanted to keep on the right side of them.

One day, the wolves in the Forest of Menmuir ventured out, and ripped a flock of the king’s sheep to shreds. All the lords of Angus were called to a great wolf-hunt to seek the culprits, and they were told to bring their best hunters with them. So the word was sent round that Sir Crawford wanted hunters to meet at the castle gates before the hunt, and the young men of Edzell duly gathered there, all carrying fine spears and javelins. As the band of hunters prepared to leave, up walked the twins. They had no fine weaponry. Each carried a big rough sack over one shoulder, and had a knife tucked into their belt. This was all they brought. The other young men scoffed and giggled at the sight of them, and all stared openly at the birthmarks on their faces. But Crawford knew there was more to them than met the eye.

As the hunting party made their way into the glen and along the north spur of the White Caterthun Hill, there they sighted a pack of wolves prowling in the trees. Crawford directed six men to block their escape routes, then guided the rest of the hunting party to back the wolves into a clearing where they would be trapped. Crawford’s hunting dogs set about them, but the wolves fought well, sinking their yellow teeth into the dogs’ throats, moving too fast to be caught by the party’s spears.

Then the twins crept forward, gesturing that the others should hang back. Their footsteps fell dead silent in the forest. Then they took the sacks from their shoulders and held them open. From each sack flew seven huge hawks. In an instant, each hawk made for a different wolf, gripping talons into their necks until their white fur stained red, pecking at the eyes of the wolves until they hung down on their stalks. The forest echoed with howls. As the blinded, hopeless wolves staggered around, the twins ran forward and slit their throats with their knives. Crawford and his men stood aghast through all this. They had seen nothing like it before.

At the end of the day’s wolf hunt, the men of Edzell were the undoubted champions. Some parties caught one or two wolves, while others returned empty-handed, but Crawford’s men could hardly move under the weight of the wolf-bodies they carried home.

But even after this success, the twins and their mother were not truly welcomed into the community. Lord Crawford, seeing their power, appointed them hunters-in-chief on his estate. But neither he nor his wife ever tried to extend a hand in friendship, and nor did the other folk in the village.

As time went by, another rumour was added to those of the family’s eerie powers. Folk said the twins were doing some unofficial hunting of their own, out of sight of Lord Crawford, selling deer from the estate around the small settlements further up the glen. Crawford had them watched day and night, but it was no easy task to catch such good hunters in the act. They knew immediately when they were being followed.

One night, a windy night in late September when the full moon lit the sky, Crawford held a great ball in Edzell Castle to celebrate the end of the harvest. The lord and lady and their guests gathered inside, and, on the green outside, the servants and farm workers from Crawford’s estate held their own dances. The only ones missing were the twins and their mother. In their absence, everyone’s minds were on them. What did they get up to, these strange people who would not join them on a night like this? The other estate workers decided to do a bit of spying. They crept into the woods and hid behind trees, surrounding the little cottage where the twins lived with their mother.

After a while, the two young men emerged out of the forest. Between them they held a huge red stag, its antlers spreading like branches. It had been killed by a single arrow to its heart. As they came near to the door of their cottage, their fellow workers rushed from the trees and set upon them. Though either of the twins could easily have fought off three other men, they were far outnumbered. The mob tied their hands and feet together and carried them off to the castle, along with the stag as evidence. They called for Lord Crawford to come out from the midst of the dance, to see what his chief hunters had done. He sent them down to be held in the castle dungeon, awaiting their fate the following morning.

For hunting the lord’s deer without his permission, the punishment was death. They were to be hanged from a tall oak tree beside the castle. The crowd who had betrayed them the night before were only too happy to hear that they would finally be rid of the twins. At first light, the hangman set about his grim task, while Lord and Lady Crawford looked out from the castle window.

As their bodies hung in the breeze, the twins’ mother came rushing out of the forest. At once, she saw she was too late to save her beloved sons. Standing below the window, she pointed her finger at the Lord and Lady Crawford and howled with unearthly fury.

‘By all the demons of hell you will be cursed! Lady Crawford, may you know the pain of seeing your bairn die. And Lord Crawford – may you die the most fearful death any man born of woman ever knew!’

Although Crawford’s men made to grab her, the twins’ mother slipped from their grasp and darted back into the shadow of the forest. It was the last she was ever seen or heard of in Edzell.

But her words remained in the Crawfords’ minds. Before that week was out, both Lady Crawford and her young son were gravely ill. The child died and his grieving mother followed a day or so later, and the two were buried in one grave.

But Lord Crawford lived, and he mourned his wife and child for a year before he began the search for a new bride to carry on his lineage. He got engaged to the daughter of a minor noble from the west, and they made plans for a wedding. As part of the celebrations, he declared they would have a hunting party, the first to go out in Edzell since the twins had died.

On a bright autumn morning, Crawford led his party into the forest. Soon they saw a stag break cover, flashing out from among the trees. Off they went after it. The stag led the hunting party into the glen, towards the White Caterthun Hill, until Crawford realised it had led them to the same clearing where the twins had killed the wolves two years before. He shot an arrow and made his target, and the deer fell to the ground. But the place made him feel uneasy. Before he knew what was happening, two ferocious wolves were upon him. They dragged him from his horse with their teeth, ripping his cloak to shreds and then biting into his flesh. By the time his companions heard his screams, Lord Crawford was unrecognisable. The wolves tore him limb from limb and the forest floor was awash with blood.

The hunting party fled in terror, with no choice but to leave Crawford to his fate. When they told their story later, they said that they would know the wolves again, for one had a bright white spot of fur on its cheek, and the other had the same mark on its forehead.

The old Edzell Castle is now gone, replaced by a more modern building, and the oak tree gone with it. But for centuries after these events, on stormy moonlit nights, the spirits of the twins were seen signing to one another beneath its branches, and the forest would echo with the howls of wolves.

THE CRYING BANSHEE OF GLENISLA

This is one of Stanley Robertson’s stories. In fact, the young man who it happened to was Stanley’s grandfather.

One autumn, a young Traveller man was making his way alone through Glenisla. Autumn days are beautiful in the glens, but at night, the cold and the winds are a danger. It was a dreich night he found himself out on, and rain was battering down. His feet ached from a long day’s walking and his hands were red raw from making the besoms he sold, and the cold and the wet made his hands and feet hurt even more.

He didn’t see another soul on the road through Glenisla, just the steep braes looming up on either side of him and the burn running along beside him. There was barely even a bird or a fox for company. He knew some of his family would be camped five or six miles along the glen, but the thought of walking that far was too much. So the man made up his mind that he was going to stop in at the next shelter he came to, whether that meant making up a camp by himself or asking if he could sleep in someone’s barn. After a while he caught sight of a wee house that was set a bit back from the road. He hoped there would be a fire on inside and maybe a bite to eat. But when he approached it he saw his luck was out again. It was an old bothy, one of the ones that the unmarried farm workers lived in. But this one had been abandoned for years, and the windows were boarded shut. The farmhouse itself, not far away, was just a pile of rubble.

‘Och well,’ the man thought to himself. ‘I’ve spent the night in worse places, this’ll do me.’

So he went inside the bothy and looked around. There was an old-fashioned fireplace, and he did his best to scrape out the dirt and set a fire going with the driest bits of heather he could find. Soon he was getting warmed up and the room was smoky from the wind blowing back down the chimney. It felt so good to be inside in the warm.

But the old door was swinging to and fro with a creak and a bang, and it was letting a cold draught in that cut through the heat from the fire. He ventured out into the night again and got a big, round stone, so heavy he had to stagger with it, and he heaved that inside and set it against the door to jam it shut. Peace at last. He took out his pipe and dug in his pack for a bite to eat. It was beginning to feel quite cosy in there, and soon he lay down by the fire and drifted off to sleep.

Bang, bang, bang! He woke up to an almighty noise at the bothy door. It was the dead of night, almost pitch dark apart from a bit of light from the embers of the fire. Whatever it was kept battering at the door like it was going to break it down.

The young man lay stock still. The noise was far too loud to be a human knock. Then suddenly it fell dead silent, so quiet he thought there could be no life for miles. And in that silence, a low, mournful howl started to echo through the glen.

‘It must be the wind coming doon the lum,’ he told himself. ‘It’s just the wind.’

Then came the bang, bang, bang of whatever was crashing against the door. He thought the door was about to come clean off its hinges. And then he realised that the wind couldn’t be coming down the lum and crashing against the door at the same time, for those were two different sides of the bothy. His instinct told him he wasn’t safe where he was beside the fire, and he crept off towards the other end of the room. The door kept bang, bang, banging away.

For a few minutes, all was quiet. But then, the mournful howl came again, drifting through the night air and sending a chill into his bones that went deeper than the cold. It howled and sobbed, and then the crashing at the door started again. He was absolutely petrified by now, pressed up against the wall as far away from the door as he could get, praying whatever it was wouldn’t make it in.

Then – crash! Even louder than before, and the door burst open. The big stone he’d put against the door came flying through the air and smashed down into the hearth. It landed just where his head had been minutes before. If he had still been lying by the fire, that would have been the end of him.

The night was silent again. But the young man was not going to hang around and find out what might come next. He got to his feet and picked up his basket. As he stepped out of the bothy door, he heard the voice moaning and howling, further away now.

‘I’d better get away afore it comes back this way,’ he said to himself, and made for the road. And then he saw it. The ghost. It was a huge white shape sweeping across the glen and it was crossing over and over the roof of the bothy. Every time it flew over the roof, the doors and windows shook as if the whole place was about to fall down. He shuddered to think it had been right over his head while he’d been in there.

Now his sore feet were the least of his worries, and he ran down the road and through bushes and streams and ditches towards where his family had said they’d be camping. Whatever would get him away from that bothy the fastest was the route he took. He didn’t take a minute’s rest until he got there. When he arrived, so relieved to see another living soul, he saw the folk there were all packing up their tents and getting ready to leave again too.

‘Oh, you’re here,’ they said. ‘Just as well. We’re no biding here, there’s a crying banshee in Glenisla tonight.’

They had seen the spectre too, and heard it crying up and down the glen all night. They told him it had been blowing their tents down and howling around the camp. When it had been quiet at the bothy, the banshee had been down at their camp, and when it had been quiet there it had been up crashing and banging at the bothy door. The banshee was a lonely spirit, the ghost of someone who had died without kith or kin. This one was mourning a battle which had been lost in the glen many years before, in which the last of its people had died.

Stanley Robertson said that Glenisla and Glen Clova were always known as bad places to spend the night among the Traveller folk, because they were haunted by many such mournful banshees.

MCCOMIE MHOR

High up Glenisla, at a place called Crandart near Forter Castle, there once lived a man named Iain MacThomaidh, the head of the clan MacThomas. As the years went by, the Scots speakers of the glens passed his name down phonetically as McComie. He was known in the area as McComie Mhor, and he was famous for his many adventures across the glens of Angus and Perthshire.

Like his Gaelic name suggests, he was a big man, so big as to be almost a giant, and he always wore a red jacket with silver buttons in the style of the reivers of the glens. McComie was renowned for his strength and bravery, and when the glens held their Highland Games his athletic feats were second to none. He could pick up gigantic boulders with one hand that no one else could shift with two and hurl them far across the playing field. Near where the source of the Isla springs up, there are two such boulders still known as McComie’s Stones, which no one has been able to move in the centuries since he threw them.