Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: THP Ireland

- Kategorie: Fantasy und Science-Fiction

- Sprache: Englisch

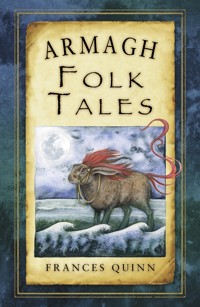

County Armagh, the Orchard County, abounds in folk tales, myths and legends and a selection of the best, drawn from historical sources and newly recorded local reminiscences, have been brought to life here by local storyteller Frances Quinn. Armagh is the place where, legend has it, the warrior king Conor Mac Nessa once ruled and where Deirdre of the Sorrows met her lover Naoise. It is where St Mochua's Well was said by some to curse as well as cure and where evidence of St Patrick's disagreement with a bull can still be seen. And it is where Mrs Lester was rudely awakened in her grave. It is also said to be the home of a plethora of strange and magical creatures and stories abound of encounters with fairies, ghosts, dragons, witches and even a giant pig. From age-old legends and fantastical myths to amusing anecdotes and cautionary tales, this collection is a heady mix of bloodthirsty, funny, passionate and moving stories. It will take you into a remarkable world where you can let your imagination run wild.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 302

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2014

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Formy fatherMick the Tailor

and

my brotherPatalias John Patrick

both moulded out ofArmagh clay

CONTENTS

Title

Dedication

Acknowledgements

Introduction

1 Legends

The Children of Lir

The Twins of Macha

Macha Mongrúad

Conor Mac Nessa

Setanta Goes to Emain

Cú Chulainn

Cúchulainn Takes Up Arms

Deirdre and the Sons of Usnach

The Naming of Lough Neagh

The Plain of Leafony

The Chase on Slieve Gullion

Not a Man at All

The Navan Dragon

The Camlough Dragon

The Black Pig’s Dyke

The Death of Fergus Mac Leide

2 Things Religious and Irreligious

The Bull’s Track

Sally Hill

Holy Wells

Praying Prayers

Stray Paths

3 Outlaws

Redmond O’Hanlon

Séamus MacMurphy

4 Humour

The New Broom Sweeps Clean

Caught in the Act

Armagh’s Little Venice

The Leapers

Drain Jumper

The Perils of Unrequited Love

5 Murder and Resurrection

Lived Once, Buried Twice

Margery McCall

The Green Lady’s

The Toulerton Murder

6 The ‘Good Folk’

The Fairy Man

Fairy Lore

Fairy Sightings by People Alive Today

Fairy Helpers

Forts and Lone Bushes

The Fairy Food

The Changeling

The Conference of Hares

7 Ghosts of the Past

Footsteps in the Dead of Night

Baleer

The Phantom Coachman

The Road to Navan

Personal Ghost Stories

The Gift

8 Local Lore

Master McGrath

The Bullets

Apple Country

Copyright

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I’d like to thank all of the following for their encouragement and/or their generosity in providing or sharing material and memories:

Davey Armstrong; Seán Barden; Jim Blaney; Ruairí and Brenda Blaney; Seán Boylan (Keady); Colette and Mark; Martin Conlon; Paddy Corrigan; Molly Cunningham; Charlie Dillon (Snr); Eileen Fagan; Seán and Maura Farrell; Pat Fearon; Mary Flanagan; Ann Gilmartin; Rosemary Gohan; Dermot Hicks; Eileen Hicks; Mary Hughes; Patricia Kennedy; Madeleine and Peter Kelly; Denis Lavery; Josephine and Peter Mackle; Seán McAteer; Criostóir Mac Carthaigh; Vincent McKeever; Pat Joe McKenna; Pat McNally; Mary McVeigh; Phil Mohan; Kay Muhr; Kevin Murphy; Mgr Raymond Murray; Colette O’Brien; Fergal and Joan O’Brien; Finn O’Gorman; Bernard O’Hanlon; John Pearson; Arthur Quinn; Margery Quinn; Michael Quinn; Greer Ramsey; Jim Smart; Jean Trainor; Hilda Winter; the staff of Armagh County Museum; The Irish Studies Library, Armagh; The Cardinal Ó Fiaich Memorial Library; the staff of The Folklore Commission, University College Dublin and Peter Carson of the Ulster Folk and Transport Museum. Lastly, a very special thanks to Patricia McConville.

PERMISSIONS

My thanks to:

Peter Murphy and the Murphy family for kind permission to reprint collected items in Now You’re Talking and My Man Jack by Michael J. Murphy.

Dundalgan Press for kind permission to reprint collected items from T.G.F. Paterson’s Country Cracks.

Patricia Kennedy for kind permission to use a story from her Of Other Days Around Us.

ILLUSTRATIONS

All illustrations are by the author.

* An impression of the Armagh coat of arms.

* Tullynawood Lake, near Sí Fionnachaidh.

* Macha’s Race.

* Murgelt the Mermaid of Lough Neagh.

* The Chase on Slieve Gullion.

* The Navan Dragon.

* The Black Pig.

* The Old and the New – the New and the Old.

* An impression of a detail from the Book of Armagh.

* A drawing of the Shrine of St Patrick’s Bell

* St Mochua’s Well.

* Miaow!

* The Armagh Gondola from an Alison Studio photograph.

* A drawing of a detail on The McAleavey Marvels poster.

* The Hare Stare.

* Master McGrath!

* Armagh bullets.

* Apple Blossom in Loughgall.

INTRODUCTION

Some places have gold or silver mines. In A rmagh our real riches lie in song and story. Seam after seam of them we have and this book is but a narrow shaft into the cultural riches of the county.

Like many counties in Ireland, stories are in the DNA of the people. The landscape is the fabric of the stories – what sews us together or unfortunately, at times, rips us apart. Stories are a way of coming to terms with our fortunes and misfortunes, and with the quirks of others; in short, a way of making sense of the human condition. It comes naturally in Ireland to be creative with language, to order a story to amuse or impress. What I think is so great about our local stories is their obvious delight in the infinite variety of human nature: from solid legends to fey fairy stories and tales which show how we relish eccentricity. Folk stories are such a great antidote to the packaged conformity and image-conscious society of today.

In putting together this collection of stories, I wanted to pay tribute to two folklorists from County Armagh: T.G.F. Paterson and Michael J. Murphy. I don’t think these two remarkable men have received anything like the acknowledgement they deserve. Kevin Murphy, in his article ‘The Last Druid’, said that Patrick Kavanagh’s remark, ‘I flew to knowledge, without going to college’ applied equally to Michael J. Murphy. Interestingly enough it applies to both Murphy and Paterson because both men left school around the age of fourteen and went on to amazing achievements and to write books. Both were offered OBEs, which Paterson accepted and Murphy declined, reflecting two points on a wide spectrum of allegiance and political outlook that exists in the North.

I have included in the collection a number of colloquial accounts taken mostly from Paterson’s Country Cracks and Murphy’s NowYou’re Talking. I see no point in changing rich local language into an anodyne standard one – society already abounds in strangulated vowels and attempts to reject regionality. I have made further mention of some of their stories in the hope that it will whet people’s appetite to go back to the very enjoyable writings of both men and I frequently make reference to Paterson’s HarvestHome – a real treasure trove.

While I was working on this project I spoke to many, many Armagh people and there wasn’t one occasion when it didn’t add to my knowledge and understanding of the place. Although it wasn’t appropriate to use all the material here, everything went into the mix and helped me enormously. Of course I have only managed to touch on a fraction of the lore of nearly 1,000 townlands!

My aim was not to produce a worthy tome or a book of academic excellence but rather a popular collection – something that is more typical of the people of the county. For this I wanted to include stories that ranged from the sublime to the ridiculous.

It was interesting that the consensus of opinion was that fairies and ghosts had gone out when electric light came in – that they had been part of an unlit country landscape when people had no transport and had to walk home at night on dark lonely roads. Now that we have electric light in houses and streets and all our modern conveniences, we are no longer victims of our imagination. Having quite confidently told me that, the same people went on to tell me about experiences they’d had where they had seen and heard supernatural things!

Before this I’d always heard that it was parents or grandparents or friends of friends who had seen ghosts or knew someone who had seen a fairy. This time – in 2013! – I was talking to people who were telling me about personal first-hand experiences. I did begin to wonder though, what with the fairy folk, the resurrections and the normal ghosts, if there was much room for ordinary folk left in the county.

It does make you reflect on ‘the digital age’ where the image-conscious are so aware of keeping up with whatever everyone else is keeping up with, that it’s necessary for them to spend nearly every minute checking it out by text or online. The reality of the moment and being in the present is forfeited for virtual reality, so we may well be on the way to losing our sensitivity to the atmosphere around us.

Listening to people’s experiences of life in the past was an enormously enjoyable experience, especially when it was from seventy-, eighty- and ninety-year-olds and the ninety-year-olds, in particular were so young at heart!

1

LEGENDS

T

2

THINGS RELIGIOUSAND IRRELIGIOUS

Armagh is the ecclesiastical capital of Ireland. It appears to have been a religious centre down through the ages and has had significance not only for Christians but for the pre-Christian era as well. The early Christians in Ireland very cleverly incorporated much of the native religion and customs into the form of Christianity they taught, and their Christianity was considerably different from that taught later.

It was generally thought that the Navan Fort (Emain Macha), was the dwelling of Conor Mac Nessa and the Red Branch knights (the Craobh Rua) in the Iron Age but there has been a great deal of controversy over this. When archaeologists were excavating the site, they came upon what they deduced to be a ceremonial structure. It was a limestone cairn within a 40m wooden structure and they concluded that it was used for some type of religious ritual. Whether it was because the area had religious significance or because it was a seat of political power, or a little of both, St Patrick decided to build a church in Armagh.

THE BULL’S TRACK

There’s a hardly credible yet oft-told story about the first church St Patrick built. Perhaps it was to explain the mark of a bull’s hoof in the ground at Ballymacnab: a townland 7 miles outside Armagh City where today there is a junction of two roads beside a church. The track seems to have been there for centuries – perhaps through the ages – and it’s known as the Bull’s Track or the Bull’s Foot.

The story goes that St Patrick tried to build his church at Armaghbreague (this comes from the Gaelic meaning ‘false Armagh’). The men worked at the building every day, and every night a bull would come and knock it down. St Patrick tried to tackle the bull with the support of the local people but the bull rampaged through the countryside for miles around. It leaped from one site to another, leaving the mark of its hoof in several places the best known of which is at Ballymacnab. It has been suggested that the bull represented the hostility of the local pagan population to this new ‘Christianity’.

The following version of that story was collected in South Armagh and appears on p.99 of Michael J. Murphy’s Now You’re Talking … (Blackstaff Press, 1975). It mentions Oisín, who was one of the more famous members of the Fianna and grandson to Fionn Mac Cumhail (Finn son of Cumhal).

The time St Patrick met Oisín and converted him, Oisín had turned into a very old man; and St Patrick was building his church at Armagh at the time.

But he was getting no further with the work; every blessed night this bull would come out of the woods and cowp [overturn] and scatter all they had built during the day.

Patrick was beat. And in the latter end he said his only remedy was to ask Oisín if he could do anything about this wild bull: Oisín was a giant of a man you understand, a powerful man altogether in his days with Finn and the Fianna, before he went to Tír na n-Óg [The Land of Youth].

Well, Oisín good enough heard the story, and he allowed he thought he’d be fit for the bull if only St Patrick would pray for him to have the strength of twenty men of that day.

St Patrick said he would, and away he goes to pray for Oisín to get the strength of the twenty men, and the Lord heard his prayer and Oisín got the strength of the twenty men of that day.

But it was no good: the bull came that night after Oisín bet [beat] it away and knocked and scattered what they’d built that day the same as usual.

So Oisín asked St Patrick to pray that he might have his old strength back again. And St Patrick went away and he prayed hard, and Oisín’s former strength was given back to him, restored, the same as it was before he went to Tír na n-Óg.

And that night he faced the bull again; and it was a long hard fight and in the end an – dammit he mastered the bull and the Divil’s own fight he had to kill it.

But before Oisín killed the bull it seen it was at last meeting its match and when it could do no more it give a lep [leap], a wild lep at Armaghbreague, and the track of its hooves is to be seen in the rock of the mountain there to this day.

Oisín killed the bull, but he was done out. So he skinned the bull and put the hide about him like a cloak and made his way back to where St Patrick had the masons building his church. He was that far through [exhausted] he could go no further, so he lay down with the hide of the bull about him, and in no time he was sound asleep.

The following morning early St Patrick’s men come again to start at the building of the church: and there was Oisín, as sound as the bells, asleep and snoring.

Then St Patrick come up and he seen what had happened and Oisín asleep. He told the men for to creep up and by all and any means take the cloak off Oisín: he was afeared what might happen if Oisín awoke and the power still on him.

So they crept up. Oisín was still snoring; and he sucked the men up to him, and when he snored out with every breath he pushed them back again; in and out. And St Patrick seen it and the men, Oisín’s snores sucking them in, his breath blowing them out: in and out, in and out.

There was only one thing he could do. He went away to pray; and if he prayed hard the first time for Oisín to get back his strength to beat the bull he prayed twice and three times as hard for the Lord to take the strength away from Oisín while he slept, for God only knows what notion Oisín might take into his head when he’d waken.

And St Patrick’s prayer was heard.

Well be that as it may, in most versions of the story the bull was successful in destroying the church which was being built on Armaghbreague and the bull was en route to Emain Macha when he left his track on the ground. In any case, St Patrick was still on a mission to find a bull-free zone where he might build his church.

SALLY HILL

Around AD 445 St Patrick sought permission from Dáire, a wealthy local chieftain, to site his church on Druim Saileach (Hill of the Sallies or Willows). Dáire, however, refused him. He did allow him, though, to site it far below, near the bottom of that hill in what today is Scotch Street. It was called Teampall Na Fearta (Church of the Holy Relics). It subsequently became a monastery and then a convent until the dissolution of religious houses in the sixteenth century. In the recent past it was the site of the Bank of Ireland and today it’s a home for the elderly called St Patrick’s Fold.

According to tradition, St Patrick’s sister, Lupita, was buried there. Indeed, in the early days the body of a female was exhumed. It had been buried in a vertical position with two crosses: one in front of and the other behind the body. The surmise was that it was Lupita but there was no evidence for that. In 1633, according to James Stuart’s History of Armagh, another body was exhumed. It was that of a woman and the body was still intact; however, when ‘profane hands’ touched the body, it disintegrated. Many believed that the miraculously preserved body proved that this had been Lupita.

Patrick was persistent in his crusade to obtain Sally Hill and he visited Dáire’s house often. There’s a story told about one of Dáire’s servants allowing his horse to graze on the ground Patrick had been given for his church. Patrick protested to him but he was ignored and the horse was left there overnight. When the servant came for his horse next morning it was lying dead, so he rushed off to report this offence to Dáire, who was furious and ordered Patrick to be killed.

No sooner had the man left to carry out his wishes, than Dáire himself was struck down and his wife said it was because of the power of Patrick. She cancelled Dáire’s order to kill him and instead made a plea for him to restore her husband. Patrick is supposed to have blessed some water and told the servant to sprinkle it on the horse, which revived on the spot. Then some was sprinkled on Dáire, where it had a similar effect.

3

OUTLAWS

R

4

HUMOUR

I was delighted to come across the following two stories in the Journal of Keady & District Historical Society (1993). They were written by Tommy O’Reilly. I have stayed reasonably close to the original text. Tommy has sadly passed on now but I hope these stories will keep the memory of him alive.

THE NEW BROOM SWEEPS CLEAN