2,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Renard Press

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

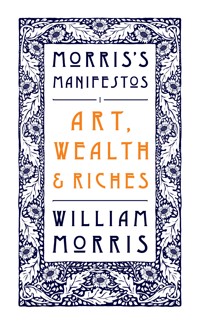

William Morris is perhaps best known today for the beautiful textile designs he created under the banner of Morris & Co, which continue to decorate homes around the globe. As one of the leading lights of British socialism, however, he is less well known, and this series of Morris's Manifestos seeks to highlight his extraordinary contribution to the literary canon on subjects socialist and artistic. Based on a lecture given at the Manchester Royal Institution in 1883, Art, Wealth and Riches is a thought-provoking essay that considers art as having educative and aesthetic value that should be shared with the many, rather than financial value that should be hoarded by the few. Morris asks: 'Is art to be limited to a narrow class who only care for it in a very languid way, or is it to be the solace and pleasure of the whole people?'

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 44

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Ähnliche

Art, Wealth and Riches

william morris

renard press

Renard Press Ltd

124 City Road

London EC1V 2NX

United Kingdom

020 8050 2928

www.renardpress.com

Art, Wealth and Riches first published in 1883

This edition first published by Renard Press Ltd in 2022

Edited text and Notes © Renard Press Ltd, 2022

Cover by Will Dady, after a design by William Morris

Renard Press is proud to be a climate positive publisher, removing more carbon from the air than we emit and planting a small forest. For more information see renardpress.com/eco.

All rights reserved. This publication may not be reproduced, used to train artificial intelligence systems or models, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form or by any means – electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise – without the prior permission of the publisher.

EU Authorised Representative: Easy Access System Europe – Mustamäe tee 50, 10621 Tallinn, Estonia, [email protected].

contents

Art, Wealth and Riches

Notes

A Brief Biographical Sketch of William Morris

An address delivered at a joint conversazione of Manchester societies at the Royal Institution, Manchester,* 6th March 1883

Art, wealth and riches are the words I have written at the head of this paper. Some of you may think that the two latter words, wealth and riches, are tautologous; but I cannot admit it. In truth there are no real synonyms in any language – I mean, unless in the case of words borrowed from another tongue – and in the early days of our own language no one would have thought of using the word rich as a synonym for wealthy. He would have understood a wealthy man to mean one who had plentiful livelihood, and a rich man one who had great dominion over his fellow men. Alexander the Rich, Canute the Rich, Alfred the Rich;* these are familiar words enough in the early literature of the North; the adjective would scarcely be used except of a great king or chief, a man pre-eminent above other kings and chiefs. Now, without being a stickler for etymological accuracy, I must say that I think there are cases where modern languages have lost power by confusing two words into one meaning, and that this is one of them. I shall ask your leave, therefore, to use the words wealth and riches somewhat in the way in which our forefathers did, and to understand wealth as signifying the means of living a decent life, and riches the means for exercising dominion over other people. Thus understood the words are widely different to my mind; yet, indeed, if you say that the difference is but one of degree I must needs admit it; just so it is between the shepherd’s dog and the wolf. Their respective views on the subject of mutton differ only in degree.

Anyhow, I think the following question is an important one: Which shall art belong to, wealth or riches? Whose servant shall she be? Or rather, Shall she be the slave of riches, or the friend and helpmate of wealth? Indeed, if I put the question in another form, and ask: Is art to be limited to a narrow class who only care for it in a very languid way, or is it to be the solace and pleasure of the whole people? The question finally comes to this: Are we to have art or the pretence of art? It is like enough that to many or even most of you the question will seem of no practical importance. To most people the present condition of art does seem in the main to be the only condition it could exist in among cultivated people, and they are (in a languid way, as I said) content with its present aims and tendencies. For myself, I am so discontented with the present conditions of art, and the matter seems to me so serious, that I am forced to try to make other people share my discontent, and am this evening risking the committal of a breach of good manners by standing before you, grievance in hand, on an occasion like this, when everybody present, I feel sure, is full of goodwill both towards the arts and towards the public. My only excuse is my belief in the sincerity of your wish to know any serious views that can be taken of a matter so important. So I will say that the question I have asked, whether art is to be the helpmate of wealth or the slave of riches, is of great practical import, if indeed art is important to the human race, which I suppose no one here will gainsay.

Now I will ask those who think art is in a normal and healthy condition to explain the meaning of the enthusiasm (which I am glad to learn the people of Manchester share) shown of late years for the foundation and extension of museums, a great part of whose contents is but fragments of the household goods of past ages. Why do cultivated, sober, reasonable people, not lacking in a due sense of the value of money, give large sums for scraps of figured cloth, pieces of roughly made pottery, worm-eaten carving, or battered metalwork, and treasure them up in expensive public buildings under the official guardianship of learned experts? Well, we all know that these things are supposed to teach us something; they are educational. The type of all our museums, that at South Kensington, is distinctly