Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Tacet Books

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Serie: Essential Novelists

- Sprache: Englisch

Welcome to the Essential Novelists book series, were we present to you the best works of remarkable authors. For this book, the literary critic August Nemo has chosen the two most important and meaningful novels of William Morris wich are A Tale of The House of the Wolfings and All the Kindreds of the Mark and The Wood Beyond the World. William Morris was a British textile designer, poet, novelist, translator, and socialist activist associated with the British Arts and Crafts Movement. His literary contributions helped to establish the modern fantasy genre, while he played a significant role propagating the early socialist movement in Britain. Novels selected for this book: - A Tale of The House of the Wolfings and All the Kindreds of the Mark. - The Wood Beyond the World. This is one of many books in the series Essential Novelists. If you liked this book, look for the other titles in the series, we are sure you will like some of the authors.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 678

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2020

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Table of Contents

Title Page

Author

A Tale of The House of the Wolfings and All the Kindreds of the Mark

The Wood Beyond the World

About the Publisher

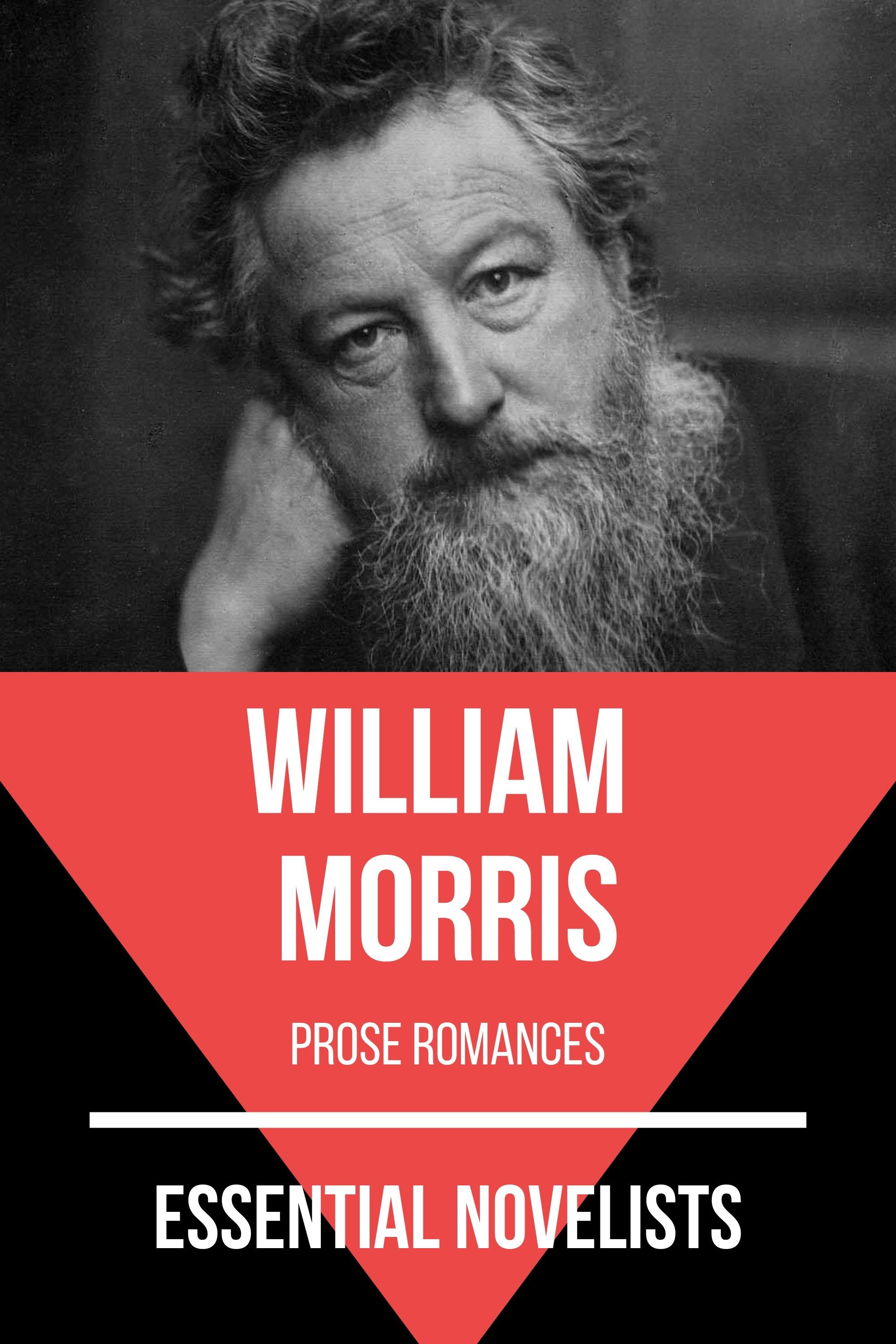

Author

William Morris (24 March 1834 – 3 October 1896) was a British textile designer, poet, novelist, translator, and socialist activist associated with the British Arts and Crafts Movement. He was a major contributor to the revival of traditional British textile arts and methods of production. His literary contributions helped to establish the modern fantasy genre, while he played a significant role propagating the early socialist movement in Britain.

Morris was born in Walthamstow, Essex to a wealthy middle-class family. He came under the strong influence of medievalism while studying Classics at Oxford University, there joining the Birmingham Set. After university, he trained as an architect, married Jane Burden, and developed close friendships with Pre-Raphaelite artists Edward Burne-Jones and Dante Gabriel Rossetti and with Neo-Gothic architect Philip Webb. Webb and Morris designed Red House in Kent where Morris lived from 1859 to 1865, before moving to Bloomsbury, central London. In 1861, Morris founded the Morris, Marshall, Faulkner & Co decorative arts firm with Burne-Jones, Rossetti, Webb, and others, which became highly fashionable and much in demand. The firm profoundly influenced interior decoration throughout the Victorian period, with Morris designing tapestries, wallpaper, fabrics, furniture, and stained glass windows. In 1875, he assumed total control of the company, which was renamed Morris & Co.

Morris rented the rural retreat of Kelmscott Manor, Oxfordshire from 1871 while also retaining a main home in London. He was greatly influenced by visits to Iceland with Eiríkr Magnússon, and he produced a series of English-language translations of Icelandic Sagas. He also achieved success with the publication of his epic poems and novels, namely The Earthly Paradise (1868–1870), A Dream of John Ball (1888), the Utopian News from Nowhere (1890), and the fantasy romance The Well at the World's End (1896). In 1877, he founded the Society for the Protection of Ancient Buildings to campaign against the damage caused by architectural restoration. He embraced Marxism and was influenced by anarchism in the 1880s and became a committed revolutionary socialist activist. He founded the Socialist League in 1884 after an involvement in the Social Democratic Federation (SDF), but he broke with that organization in 1890. In 1891, he founded the Kelmscott Press to publish limited-edition, illuminated-style print books, a cause to which he devoted his final years.

Morris is recognised as one of the most significant cultural figures of Victorian Britain. He was best known in his lifetime as a poet, although he posthumously became better known for his designs. The William Morris Society founded in 1955 is devoted to his legacy, while multiple biographies and studies of his work have been published. Many of the buildings associated with his life are open to visitors, much of his work can be found in art galleries and museums, and his designs are still in production.

A Tale of The House of the Wolfings and All the Kindreds of the Mark

Chapter I. The Dwellings of Mid-Mark

––––––––

The tale tells that in times long past there was a dwelling of men beside a great wood. Before it lay a plain, not very great, but which was, as it were, an isle in the sea of woodland, since even when you stood on the flat ground, you could see trees everywhere in the offing, though as for hills, you could scarce say that there were any; only swellings-up of the earth here and there, like the upheavings of the water that one sees at whiles going on amidst the eddies of a swift but deep stream.

On either side, to right and left the tree-girdle reached out toward the blue distance, thick close and unsundered, save where it and the plain which it begirdled was cleft amidmost by a river about as wide as the Thames at Sheene when the flood-tide is at its highest, but so swift and full of eddies, that it gave token of mountains not so far distant, though they were hidden. On each side moreover of the stream of this river was a wide space of stones, great and little, and in most places above this stony waste were banks of a few feet high, showing where the yearly winter flood was most commonly stayed.

You must know that this great clearing in the woodland was not a matter of haphazard; though the river had driven a road whereby men might fare on each side of its hurrying stream. It was men who had made that Isle in the woodland.

For many generations the folk that now dwelt there had learned the craft of iron-founding, so that they had no lack of wares of iron and steel, whether they were tools of handicraft or weapons for hunting and for war. It was the men of the Folk, who coming adown by the river-side had made that clearing. The tale tells not whence they came, but belike from the dales of the distant mountains, and from dales and mountains and plains further aloof and yet further.

Anyhow they came adown the river; on its waters on rafts, by its shores in wains or bestriding their horses or their kine, or afoot, till they had a mind to abide; and there as it fell they stayed their travel, and spread from each side of the river, and fought with the wood and its wild things, that they might make to themselves a dwelling-place on the face of the earth.

So they cut down the trees, and burned their stumps that the grass might grow sweet for their kine and sheep and horses; and they diked the river where need was all through the plain, and far up into the wild-wood to bridle the winter floods: and they made them boats to ferry them over, and to float down stream and track up-stream: they fished the river’s eddies also with net and with line; and drew drift from out of it of far-travelled wood and other matters; and the gravel of its shallows they washed for gold; and it became their friend, and they loved it, and gave it a name, and called it the Dusky, and the Glassy, and the Mirkwood-water; for the names of it changed with the generations of man.

There then in the clearing of the wood that for many years grew greater yearly they drave their beasts to pasture in the new-made meadows, where year by year the grass grew sweeter as the sun shone on it and the standing waters went from it; and now in the year whereof the tale telleth it was a fair and smiling plain, and no folk might have a better meadow.

But long before that had they learned the craft of tillage and taken heed to the acres and begun to grow wheat and rye thereon round about their roofs; the spade came into their hands, and they bethought them of the plough-share, and the tillage spread and grew, and there was no lack of bread.

In such wise that Folk had made an island amidst of the Mirkwood, and established a home there, and upheld it with manifold toil too long to tell of. And from the beginning this clearing in the wood they called the Mid-mark: for you shall know that men might journey up and down the Mirkwood-water, and half a day’s ride up or down they would come on another clearing or island in the woods, and these were the Upper-mark and the Nether-mark: and all these three were inhabited by men of one folk and one kindred, which was called the Mark-men, though of many branches was that stem of folk, who bore divers signs in battle and at the council whereby they might be known.

Now in the Mid-mark itself were many Houses of men; for by that word had they called for generations those who dwelt together under one token of kinship. The river ran from South to North, and both on the East side and on the West were there Houses of the Folk, and their habitations were shouldered up nigh unto the wood, so that ever betwixt them and the river was there a space of tillage and pasture.

Tells the tale of one such House, whose habitations were on the west side of the water, on a gentle slope of land, so that no flood higher than common might reach them. It was straight down to the river mostly that the land fell off, and on its downward-reaching slopes was the tillage, “the Acres,” as the men of that time always called tilled land; and beyond that was the meadow going fair and smooth, though with here and there a rising in it, down to the lips of the stony waste of the winter river.

Now the name of this House was the Wolfings, and they bore a Wolf on their banners, and their warriors were marked on the breast with the image of the Wolf, that they might be known for what they were if they fell in battle, and were stripped.

The house, that is to say the Roof, of the Wolfings of the Mid-mark stood on the topmost of the slope aforesaid with its back to the wild-wood and its face to the acres and the water. But you must know that in those days the men of one branch of kindred dwelt under one roof together, and had therein their place and dignity; nor were there many degrees amongst them as hath befallen afterwards, but all they of one blood were brethren and of equal dignity. Howbeit they had servants or thralls, men taken in battle, men of alien blood, though true it is that from time to time were some of such men taken into the House, and hailed as brethren of the blood.

Also (to make an end at once of these matters of kinship and affinity) the men of one House might not wed the women of their own House: to the Wolfing men all Wolfing women were as sisters: they must needs wed with the Hartings or the Elkings or the Bearings, or other such Houses of the Mark as were not so close akin to the blood of the Wolf; and this was a law that none dreamed of breaking. Thus then dwelt this Folk and such was their Custom.

As to the Roof of the Wolfings, it was a great hall and goodly, after the fashion of their folk and their day; not built of stone and lime, but framed of the goodliest trees of the wild-wood squared with the adze, and betwixt the framing filled with clay wattled with reeds. Long was that house, and at one end anigh the gable was the Man’s-door, not so high that a man might stand on the threshold and his helmcrest clear the lintel; for such was the custom, that a tall man must bow himself as he came into the hall; which custom maybe was a memory of the days of onslaught when the foemen were mostly wont to beset the hall; whereas in the days whereof the tale tells they drew out into the fields and fought unfenced; unless at whiles when the odds were over great, and then they drew their wains about them and were fenced by the wain-burg. At least it was from no niggardry that the door was made thus low, as might be seen by the fair and manifold carving of knots and dragons that was wrought above the lintel of the door for some three foot’s space. But a like door was there anigh the other gable-end, whereby the women entered, and it was called the Woman’s-door.

Near to the house on all sides except toward the wood were there many bowers and cots round about the penfolds and the byres: and these were booths for the stowage of wares, and for crafts and smithying that were unhandy to do in the house; and withal they were the dwelling-places of the thralls. And the lads and young men often abode there many days and were cherished there of the thralls that loved them, since at whiles they shunned the Great Roof that they might be the freer to come and go at their pleasure, and deal as they would. Thus was there a clustering on the slopes and bents betwixt the acres of the Wolfings and the wild-wood wherein dwelt the wolves.

As to the house within, two rows of pillars went down it endlong, fashioned of the mightiest trees that might be found, and each one fairly wrought with base and chapiter, and wreaths and knots, and fighting men and dragons; so that it was like a church of later days that has a nave and aisles: windows there were above the aisles, and a passage underneath the said windows in their roofs. In the aisles were the sleeping-places of the Folk, and down the nave under the crown of the roof were three hearths for the fires, and above each hearth a luffer or smoke-bearer to draw the smoke up when the fires were lighted. Forsooth on a bright winter afternoon it was strange to see the three columns of smoke going wavering up to the dimness of the mighty roof, and one maybe smitten athwart by the sunbeams. As for the timber of the roof itself and its framing, so exceeding great and high it was, that the tale tells how that none might see the fashion of it from the hall-floor unless he were to raise aloft a blazing faggot on a long pole: since no lack of timber was there among the men of the Mark.

At the end of the hall anigh the Man’s-door was the dais, and a table thereon set thwartwise of the hall; and in front of the dais was the noblest and greatest of the hearths; (but of the others one was in the very midmost, and another in the Woman’s-Chamber) and round about the dais, along the gable-wall, and hung from pillar to pillar were woven cloths pictured with images of ancient tales and the deeds of the Wolfings, and the deeds of the Gods from whence they came. And this was the fairest place of all the house and the best-beloved of the Folk, and especially of the older and the mightier men: and there were tales told, and songs sung, especially if they were new: and thereto also were messengers brought if any tidings were abroad: there also would the elders talk together about matters concerning the House or the Mid-mark or the whole Folk of the Markmen.

Yet you must not think that their solemn councils were held there, the folk-motes whereat it must be determined what to do and what to forbear doing; for according as such councils, (which they called Things) were of the House or of the Mid-mark or of the whole Folk, were they held each at the due Thing-steads in the Wood aloof from either acre or meadow, (as was the custom of our forefathers for long after) and at such Things would all the men of the House or the Mid-mark or the Folk be present man by man. And in each of these steads was there a Doomring wherein Doom was given by the neighbours chosen, (whom now we call the Jury) in matters between man and man; and no such doom of neighbours was given, and no such voice of the Folk proclaimed in any house or under any roof, nor even as aforesaid on the tilled acres or the depastured meadows. This was the custom of our forefathers, in memory, belike, of the days when as yet there was neither house nor tillage, nor flocks and herds, but the Earth’s face only and what freely grew thereon.

But over the dais there hung by chains and pulleys fastened to a tie-beam of the roof high aloft a wondrous lamp fashioned of glass; yet of no such glass as the folk made then and there, but of a fair and clear green like an emerald, and all done with figures and knots in gold, and strange beasts, and a warrior slaying a dragon, and the sun rising on the earth: nor did any tale tell whence this lamp came, but it was held as an ancient and holy thing by all the Mark-men, and the kindred of the Wolf had it in charge to keep a light burning in it night and day for ever; and they appointed a maiden of their own kindred to that office; which damsel must needs be unwedded, since no wedded woman dwelling under that roof could be a Wolfing woman, but would needs be of the houses wherein the Wolfings wedded.

This lamp which burned ever was called the Hall-Sun, and the woman who had charge of it, and who was the fairest that might be found was called after it the Hall-Sun also.

At the other end of the hall was the Woman’s-Chamber, and therein were the looms and other gear for the carding and spinning of wool and the weaving of cloth.

Such was the Roof under which dwelt the kindred of the Wolfings; and the other kindreds of the Mid-mark had roofs like to it; and of these the chiefest were the Elkings, the Vallings, the Alftings, the Beamings, the Galtings, and the Bearings; who bore on their banners the Elk, the Falcon, the Swan, the Tree, the Boar, and the Bear. But other lesser and newer kindreds there were than these: as for the Hartings above named, they were a kindred of the Upper-mark.

Chapter II. The Flitting of the War-Arrow

––––––––

Tells the tale that it was an evening of summer, when the wheat was in the ear, but yet green; and the neat-herds were done driving the milch-kine to the byre, and the horseherds and the shepherds had made the night-shift, and the out-goers were riding two by two and one by one through the lanes between the wheat and the rye towards the meadow. Round the cots of the thralls were gathered knots of men and women both thralls and freemen, some talking together, some hearkening a song or a tale, some singing and some dancing together; and the children gambolling about from group to group with their shrill and tuneless voices, like young throstles who have not yet learned the song of their race. With these were mingled dogs, dun of colour, long of limb, sharp-nosed, gaunt and great; they took little heed of the children as they pulled them about in their play, but lay down, or loitered about, as though they had forgotten the chase and the wild-wood.

Merry was the folk with that fair tide, and the promise of the harvest, and the joy of life, and there was no weapon among them so close to the houses, save here and there the boar-spear of some herdman or herd-woman late come from the meadow.

Tall and for the most part comely were both men and women; the most of them light-haired and grey-eyed, with cheek-bones somewhat high; white of skin but for the sun’s burning, and the wind’s parching, and whereas they were tanned of a very ruddy and cheerful hue. But the thralls were some of them of a shorter and darker breed, black-haired also and dark-eyed, lighter of limb; sometimes better knit, but sometimes crookeder of leg and knottier of arm. But some also were of build and hue not much unlike to the freemen; and these doubtless came of some other Folk of the Goths which had given way in battle before the Men of the Mark, either they or their fathers.

Moreover some of the freemen were unlike their fellows and kindred, being slenderer and closer-knit, and black-haired, but grey-eyed withal; and amongst these were one or two who exceeded in beauty all others of the House.

Now the sun was set and the glooming was at point to begin and the shadowless twilight lay upon the earth. The nightingales on the borders of the wood sang ceaselessly from the scattered hazel-trees above the greensward where the grass was cropped down close by the nibbling of the rabbits; but in spite of their song and the divers voices of the men-folk about the houses, it was an evening on which sounds from aloof can be well heard, since noises carry far at such tides.

Suddenly they who were on the edges of those throngs and were the less noisy, held themselves as if to listen; and a group that had gathered about a minstrel to hear his story fell hearkening also round about the silenced and hearkening tale-teller: some of the dancers and singers noted them and in their turn stayed the dance and kept silence to hearken; and so from group to group spread the change, till all were straining their ears to hearken the tidings. Already the men of the night-shift had heard it, and the shepherds of them had turned about, and were trotting smartly back through the lanes of the tall wheat: but the horse-herds were now scarce seen on the darkening meadow, as they galloped on fast toward their herds to drive home the stallions. For what they had heard was the tidings of war.

There was a sound in the air as of a humble-bee close to the ear of one lying on a grassy bank; or whiles as of a cow afar in the meadow lowing in the afternoon when milking-time draws nigh: but it was ever shriller than the one, and fuller than the other; for it changed at whiles, though after the first sound of it, it did not rise or fall, because the eve was windless. You might hear at once that for all it was afar, it was a great and mighty sound; nor did any that hearkened doubt what it was, but all knew it for the blast of the great war-horn of the Elkings, whose Roof lay up Mirkwood-water next to the Roof of the Wolfings.

So those little throngs broke up at once; and all the freemen, and of the thralls a good many, flocked, both men and women, to the Man’s-door of the hall, and streamed in quietly and with little talk, as men knowing that they should hear all in due season.

Within under the Hall-Sun, amidst the woven stories of time past, sat the elders and chief warriors on the dais, and amidst of all a big strong man of forty winters, his dark beard a little grizzled, his eyes big and grey. Before him on the board lay the great War-horn of the Wolfings carved out of the tusk of a sea-whale of the North and with many devices on it and the Wolf amidst them all; its golden mouth-piece and rim wrought finely with flowers. There it abode the blowing, until the spoken word of some messenger should set forth the tidings borne on the air by the horn of the Elkings.

But the name of the dark-haired chief was Thiodolf (to wit Folk-wolf) and he was deemed the wisest man of the Wolfings, and the best man of his hands, and of heart most dauntless. Beside him sat the fair woman called the Hall-Sun; for she was his foster-daughter before men’s eyes; and she was black-haired and grey-eyed like to her fosterer, and never was woman fashioned fairer: she was young of years, scarce twenty winters old.

There sat the chiefs and elders on the dais, and round about stood the kindred intermingled with the thralls, and no man spake, for they were awaiting sure and certain tidings: and when all were come in who had a mind to, there was so great a silence in the hall, that the song of the nightingales on the wood-edge sounded clear and loud therein, and even the chink of the bats about the upper windows could be heard. Then amidst the hush of men-folk, and the sounds of the life of the earth came another sound that made all turn their eyes toward the door; and this was the pad-pad of one running on the trodden and summer-dried ground anigh the hall: it stopped for a moment at the Man’s-door, and the door opened, and the throng parted, making way for the man that entered and came hastily up to the midst of the table that stood on the dais athwart the hall, and stood there panting, holding forth in his outstretched hand something which not all could see in the dimness of the hall-twilight, but which all knew nevertheless. The man was young, lithe and slender, and had no raiment but linen breeches round his middle, and skin shoes on his feet. As he stood there gathering his breath for speech, Thiodolf stood up, and poured mead into a drinking horn and held it out towards the new-comer, and spake, but in rhyme and measure:

“Welcome, thou evening-farer, and holy be thine head,

Since thou hast sought unto us in the heart of the Wolfings’ stead;

Drink now of the horn of the mighty, and call a health if thou wilt

O’er the eddies of the mead-horn to the washing out of guilt.

For thou com’st to the peace of the Wolfings, and our very guest thou art,

And meseems as I behold thee, that I look on a child of the Hart.”

But the man put the horn from him with a hasty hand, and none said another word to him until he had gotten his breath again; and then he said:

“All hail ye Wood-Wolfs’ children! nought may I drink the wine,

For the mouth and the maw that I carry this eve are nought of mine;

And my feet are the feet of the people, since the word went forth that tide,

‘O Elf here of the Hartings, no longer shalt thou bide

In any house of the Markmen than to speak the word and wend,

Till all men know the tidings and thine errand hath an end.’

Behold, O Wolves, the token and say if it be true!

I bear the shaft of battle that is four-wise cloven through,

And its each end dipped in the blood-stream, both the iron and the horn,

And its midmost scathed with the fire; and the word that I have borne

Along with this war-token is, ‘Wolfings of the Mark

Whenso ye see the war-shaft, by the daylight or the dark,

Busk ye to battle faring, and leave all work undone

Save the gathering for the handplay at the rising of the sun.

Three days hence is the hosting, and thither bear along

Your wains and your kine for the slaughter lest the journey should be long.

For great is the Folk, saith the tidings, that against the Markmen come;

In a far off land is their dwelling, whenso they sit at home,

And Welsh * is their tongue, and we wot not of the word that is in their mouth,

As they march a many together from the cities of the South.’”

* Welsh with these men means Foreign, and is used for all people of Europe who are not of Gothic or Teutonic blood.

Therewith he held up yet for a minute the token of the war-arrow ragged and burnt and bloody; and turning about with it in his hand went his ways through the open door, none hindering; and when he was gone, it was as if the token were still in the air there against the heads of the living men, and the heads of the woven warriors, so intently had all gazed at it; and none doubted the tidings or the token. Then said Thiodolf:

“Forth will we Wolfing children, and cast a sound abroad:

The mouth of the sea-beast’s weapon shall speak the battle-word;

And ye warriors hearken and hasten, and dight the weed of war,

And then to acre and meadow wend ye adown no more,

For this work shall be for the women to drive our neat from the mead,

And to yoke the wains, and to load them as the men of war have need.”

Out then they streamed from the hall, and no man was left therein save the fair Hall-Sun sitting under the lamp whose name she bore. But to the highest of the slope they went, where was a mound made higher by man’s handiwork; thereon stood Thiodolf and handled the horn, turning his face toward the downward course of Mirkwood-water; and he set the horn to his lips, and blew a long blast, and then again, and yet again the third time; and all the sounds of the gathering night were hushed under the sound of the roaring of the war-horn of the Wolfings; and the Kin of the Beamings heard it as they sat in their hall, and they gat them ready to hearken to the bearer of the tidings who should follow on the sound of the war-blast.

But when the last sound of the horn had died away, then said Thiodolf:

“Now Wolfing children hearken, what the splintered War-shaft saith,

The fire scathed blood-stained aspen! we shall ride for life or death,

We warriors, a long journey with the herd and with the wain;

But unto this our homestead shall we wend us back again,

All the gleanings of the battle; and here for them that live

Shall stand the Roof of the Wolfings, and for them shall the meadow thrive,

And the acres give their increase in the harvest of the year;

Now is no long departing since the Hall-Sun bideth here

’Neath the holy Roof of the Fathers, and the place of the Wolfing kin,

And the feast of our glad returning shall yet be held therein.

Hear the bidding of the War-shaft! All men, both thralls and free,

’Twixt twenty winters and sixty, beneath the shield shall be,

And the hosting is at the Thingstead, the Upper-mark anigh;

And we wend away to-morrow ere the Sun is noon-tide high.”

Therewith he stepped down from the mound, and went his way back to the hall; and manifold talk arose among the folk; and of the warriors some were already dight for the journey, but most not, and a many went their ways to see to their weapons and horses, and the rest back again into the hall.

By this time night had fallen, and between then and the dawning would be no darker hour, for the moon was just rising; a many of the horse-herds had done their business, and were now making their way back again through the lanes of the wheat, driving the stallions before them, who played together kicking, biting and squealing, paying but little heed to the standing corn on either side. Lights began to glitter now in the cots of the thralls, and brighter still in the stithies where already you might hear the hammers clinking on the anvils, as men fell to looking to their battle gear.

But the chief men and the women sat under their Roof on the eve of departure: and the tuns of mead were broached, and the horns filled and borne round by young maidens, and men ate and drank and were merry; and from time to time as some one of the warriors had done with giving heed to his weapons, he entered into the hall and fell into the company of those whom he loved most and by whom he was best beloved; and whiles they talked, and whiles they sang to the harp up and down that long house; and the moon risen high shone in at the windows, and there was much laughter and merriment, and talk of deeds of arms of the old days on the eve of that departure: till little by little weariness fell on them, and they went their ways to slumber, and the hall was fallen silent.

Chapter III. Thiodolf Talketh with the Wood-Sun

––––––––

But yet sat Thiodolf under the Hall-Sun for a while as one in deep thought; till at last as he stirred, his sword clattered on him; and then he lifted up his eyes and looked down the hall and saw no man stirring, so he stood up and settled his raiment on him, and went forth, and so took his ways through the hall-door, as one who hath an errand.

The moonlight lay in a great flood on the grass without, and the dew was falling in the coldest hour of the night, and the earth smelled sweetly: the whole habitation was asleep now, and there was no sound to be known as the sound of any creature, save that from the distant meadow came the lowing of a cow that had lost her calf, and that a white owl was flitting about near the eaves of the Roof with her wild cry that sounded like the mocking of merriment now silent.

Thiodolf turned toward the wood, and walked steadily through the scattered hazel-trees, and thereby into the thick of the beech-trees, whose boles grew smooth and silver-grey, high and close-set: and so on and on he went as one going by a well-known path, though there was no path, till all the moonlight was quenched under the close roof of the beech-leaves, though yet for all the darkness, no man could go there and not feel that the roof was green above him. Still he went on in despite of the darkness, till at last there was a glimmer before him, that grew greater till he came unto a small wood-lawn whereon the turf grew again, though the grass was but thin, because little sunlight got to it, so close and thick were the tall trees round about it. In the heavens above it by now there was a light that was not all of the moon, though it might scarce be told whether that light were the memory of yesterday or the promise of to-morrow, since little of the heavens could be seen thence, save the crown of them, because of the tall tree-tops.

Nought looked Thiodolf either at the heavens above, or the trees, as he strode from off the husk-strewn floor of the beech wood on to the scanty grass of the lawn, but his eyes looked straight before him at that which was amidmost of the lawn: and little wonder was that; for there on a stone chair sat a woman exceeding fair, clad in glittering raiment, her hair lying as pale in the moonlight on the grey stone as the barley acres in the August night before the reaping-hook goes in amongst them. She sat there as though she were awaiting someone, and he made no stop nor stay, but went straight up to her, and took her in his arms, and kissed her mouth and her eyes, and she him again; and then he sat himself down beside her. But her eyes looked kindly on him as she said:

“O Thiodolf, hardy art thou, that thou hast no fear to take me in thine arms and to kiss me, as though thou hadst met in the meadow with a maiden of the Elkings: and I, who am a daughter of the Gods of thy kindred, and a Chooser of the Slain! Yea, and that upon the eve of battle and the dawn of thy departure to the stricken field!”

“O Wood-Sun,” he said “thou art the treasure of life that I found when I was young, and the love of life that I hold, now that my beard is grizzling. Since when did I fear thee, Wood-Sun? Did I fear thee when first I saw thee, and we stood amidst the hazelled field, we twain living amongst the slain? But my sword was red with the blood of the foe, and my raiment with mine own blood; and I was a-weary with the day’s work, and sick with many strokes, and methought I was fainting into death. And there thou wert before me, full of life and ruddy and smiling both lips and eyes; thy raiment clean and clear, thine hands stained with blood: then didst thou take me by my bloody and weary hand, and didst kiss my lips grown ashen pale, and thou saidst ‘Come with me.’ And I strove to go, and might not; so many and sore were my hurts. Then amidst my sickness and my weariness was I merry; for I said to myself, This is the death of the warrior, and it is exceeding sweet. What meaneth it? Folk said of me; he is over young to meet the foeman; yet am I not over young to die?”

Therewith he laughed out amid the wild-wood, and his speech became song, and he said:

“We wrought in the ring of the hazels, and the wine of war we drank:

From the tide when the sun stood highest to the hour wherein she sank:

And three kings came against me, the mightiest of the Huns,

The evil-eyed in battle, the swift-foot wily ones;

And they gnashed their teeth against me, and they gnawed on the shield-rims there,

On that afternoon of summer, in the high-tide of the year.

Keen-eyed I gazed about me, and I saw the clouds draw up

Till the heavens were dark as the hollow of a wine-stained iron cup,

And the wild-deer lay unfeeding on the grass of the forest glades,

And all earth was scared with the thunder above our clashing blades.

“Then sank a King before me, and on fell the other twain,

And I tossed up the reddened sword-blade in the gathered rush of the rain

And the blood and the water blended, and fragrant grew the earth.

“There long I turned and twisted within the battle-girth

Before those bears of onset: while out from the grey world streamed

The broad red lash of the lightening and in our byrnies gleamed.

And long I leapt and laboured in that garland of the fight

’Mid the blue blades and the lightening; but ere the sky grew light

The second of the Hun-kings on the rain-drenched daisies lay;

And we twain with the battle blinded a little while made stay,

And leaning on our sword-hilts each on the other gazed.

“Then the rain grew less, and one corner of the veil of clouds was raised,

And as from the broidered covering gleams out the shoulder white

Of the bed-mate of the warrior when on his wedding night

He layeth his hand to the linen; so, down there in the west

Gleamed out the naked heaven: but the wrath rose up in my breast,

And the sword in my hand rose with it, and I leaped and hewed at the Hun;

And from him too flared the war-flame, and the blades danced bright in the sun

Come back to the earth for a little before the ending of day.

“There then with all that was in him did the Hun play out the play,

Till he fell, and left me tottering, and I turned my feet to wend

To the place of the mound of the mighty, the gate of the way without end.

And there thou wert. How was it, thou Chooser of the Slain,

Did I die in thine arms, and thereafter did thy mouth-kiss wake me again?”

Ere the last sound of his voice was done she turned and kissed him; and then she said; “Never hadst thou a fear and thine heart is full of hardihood.”

Then he said:

“’Tis the hardy heart, beloved, that keepeth me alive,

As the king-leek in the garden by the rain and the sun doth thrive,

So I thrive by the praise of the people; it is blent with my drink and my meat;

As I slumber in the night-tide it laps me soft and sweet;

And through the chamber window when I waken in the morn

With the wind of the sun’s arising from the meadow is it borne

And biddeth me remember that yet I live on earth:

Then I rise and my might is with me, and fills my heart with mirth,

As I think of the praise of the people; and all this joy I win

By the deeds that my heart commandeth and the hope that lieth therein.”

“Yea,” she said, “but day runneth ever on the heels of day, and there are many and many days; and betwixt them do they carry eld.”

“Yet art thou no older than in days bygone,” said he. “Is it so, O Daughter of the Gods, that thou wert never born, but wert from before the framing of the mountains, from the beginning of all things?”

But she said:

“Nay, nay; I began, I was born; although it may be indeed

That not on the hills of the earth I sprang from the godhead’s seed.

And e’en as my birth and my waxing shall be my waning and end.

But thou on many an errand, to many a field dost wend

Where the bow at adventure bended, or the fleeing dastard’s spear

Oft lulleth the mirth of the mighty. Now me thou dost not fear,

Yet fear with me, beloved, for the mighty Maid I fear;

And Doom is her name, and full often she maketh me afraid

And even now meseemeth on my life her hand is laid.”

But he laughed and said:

“In what land is she abiding? Is she near or far away?

Will she draw up close beside me in the press of the battle play?

And if then I may not smite her ’midst the warriors of the field

With the pale blade of my fathers, will she bide the shove of my shield?”

But sadly she sang in answer:

“In many a stead Doom dwelleth, nor sleepeth day nor night:

The rim of the bowl she kisseth, and beareth the chambering light

When the kings of men wend happy to the bride-bed from the board.

It is little to say that she wendeth the edge of the grinded sword,

When about the house half builded she hangeth many a day;

The ship from the strand she shoveth, and on his wonted way

By the mountain-hunter fareth where his foot ne’er failed before:

She is where the high bank crumbles at last on the river’s shore:

The mower’s scythe she whetteth; and lulleth the shepherd to sleep

Where the deadly ling-worm wakeneth in the desert of the sheep.

Now we that come of the God-kin of her redes for ourselves we wot,

But her will with the lives of men-folk and their ending know we not.

So therefore I bid thee not fear for thyself of Doom and her deed,

But for me: and I bid thee hearken to the helping of my need.

Or else — Art thou happy in life, or lusteth thou to die

In the flower of thy days, when thy glory and thy longing bloom on high?”

But Thiodolf answered her:

“I have deemed, and long have I deemed that this is my second life,

That my first one waned with my wounding when thou cam’st to the ring of strife.

For when in thine arms I wakened on the hazelled field of yore,

Meseemed I had newly arisen to a world I knew no more,

So much had all things brightened on that dewy dawn of day.

It was dark dull death that I looked for when my thought had died away.

It was lovely life that I woke to; and from that day henceforth

My joy of the life of man-folk was manifolded of worth.

Far fairer the fields of the morning than I had known them erst,

And the acres where I wended, and the corn with its half-slaked thirst;

And the noble Roof of the Wolfings, and the hawks that sat thereon;

And the bodies of my kindred whose deliverance I had won;

And the glimmering of the Hall-Sun in the dusky house of old;

And my name in the mouth of the maidens, and the praises of the bold,

As I sat in my battle-raiment, and the ruddy spear well steeled

Leaned ’gainst my side war-battered, and the wounds thine hand had healed.

Yea, from that morn thenceforward has my life been good indeed,

The gain of to-day was goodly, and good to-morrow’s need,

And good the whirl of the battle, and the broil I wielded there,

Till I fashioned the ordered onset, and the unhoped victory fair.

And good were the days thereafter of utter deedless rest

And the prattle of thy daughter, and her hands on my unmailed breast.

Ah good is the life thou hast given, the life that mine hands have won.

And where shall be the ending till the world is all undone?

Here sit we twain together, and both we in Godhead clad,

We twain of the Wolfing kindred, and each of the other glad.”

But she answered, and her face grew darker withal:

“O mighty man and joyous, art thou of the Wolfing kin?

’Twas no evil deed when we mingled, nor lieth doom therein.

Thou lovely man, thou black-haired, thou shalt die and have done no ill.

Fame-crowned are the deeds of thy doing, and the mouths of men they fill.

Thou betterer of the Godfolk, enduring is thy fame:

Yet as a painted image of a dream is thy dreaded name.

Of an alien folk thou comest, that we twain might be one indeed.

Thou shalt die one day. So hearken, to help me at my need.”

His face grew troubled and he said: “What is this word that I am no chief of the Wolfings?”

“Nay,” she said, “but better than they. Look thou on the face of our daughter the Hall-Sun, thy daughter and mine: favoureth she at all of me?”

He laughed: “Yea, whereas she is fair, but not otherwise. This is a hard saying, that I dwell among an alien kindred, and it wotteth not thereof. Why hast thou not told me hereof before?”

She said: “It needed not to tell thee because thy day was waxing, as now it waneth. Once more I bid thee hearken and do my bidding though it be hard to thee.”

He answered: “Even so will I as much as I may; and thus wise must thou look upon it, that I love life, and fear not death.”

Then she spake, and again her words fell into rhyme:

“In forty fights hast thou foughten, and been worsted but in four;

And I looked on and was merry; and ever more and more

Wert thou dear to the heart of the Wood-Sun, and the Chooser of the Slain.

But now whereas ye are wending with slaughter-herd and wain

To meet a folk that ye know not, a wonder, a peerless foe,

I fear for thy glory’s waning, and I see thee lying alow.”

Then he brake in: “Herein is little shame to be worsted by the might of the mightiest: if this so mighty folk sheareth a limb off the tree of my fame, yet shall it wax again.”

But she sang:

“In forty fights hast thou foughten, and beside thee who but I

Beheld the wind-tossed banners, and saw the aspen fly?

But to-day to thy war I wend not, for Weird withholdeth me

And sore my heart forebodeth for the battle that shall be.

To-day with thee I wend not; so I feared, and lo my feet,

That are wont to the woodland girdle of the acres of the wheat,

For thee among strange people and the foeman’s throng have trod,

And I tell thee their banner of battle is a wise and a mighty God.

For these are the folk of the cities, and in wondrous wise they dwell

’Mid confusion of heaped houses, dim and black as the face of hell;

Though therefrom rise roofs most goodly, where their captains and their kings

Dwell amidst the walls of marble in abundance of fair things;

And ’mid these, nor worser nor better, but builded otherwise

Stand the Houses of the Fathers, and the hidden mysteries.

And as close as are the tree-trunks that within the beech-wood thrive

E’en so many are their pillars; and therein like men alive

Stand the images of god-folk in such raiment as they wore

In the years before the cities and the hidden days of yore.

Ah for the gold that I gazed on! and their store of battle gear,

And strange engines that I knew not, or the end for which they were.

Ah for the ordered wisdom of the war-array of these,

And the folks that are sitting about them in dumb down-trodden peace!

So I thought now fareth war-ward my well-beloved friend,

And the weird of the Gods hath doomed it that no more with him may I wend!

Woe’s me for the war of the Wolfings wherefrom I am sundered apart,

And the fruitless death of the war-wise, and the doom of the hardy heart!”

Then he answered, and his eyes grew kind as he looked on her:

“For thy fair love I thank thee, and thy faithful word, O friend!

But how might it otherwise happen but we twain must meet in the end,

The God of this mighty people and the Markmen and their kin?

Lo, this is the weird of the world, and what may we do herein?”

Then mirth came into her face again as she said:

“Who wotteth of Weird, and what she is till the weird is accomplished? Long hath it been my weird to love thee and to fashion deeds for thee as I may; nor will I depart from it now.” And she sang:

“Keen-edged is the sword of the city, and bitter is its spear,

But thy breast in the battle, beloved, hath a wall of the stithy’s gear.

What now is thy wont in the handplay with the helm and the hauberk of rings?

Farest thou as the thrall and the cot-carle, or clad in the raiment of kings?”

He started, and his face reddened as he answered:

“O Wood-Sun thou wottest our battle and the way wherein we fare:

That oft at the battle’s beginning the helm and the hauberk we bear;

Lest the shaft of the fleeing coward or the bow at adventure bent

Should slay us ere the need be, ere our might be given and spent.

Yet oft ere the fight is over, and Doom hath scattered the foe,

No leader of the people by his war-gear shall ye know,

But by his hurts the rather, from the cot-carle and the thrall:

For when all is done that a man may, ’tis the hour for a man to fall.”

She yet smiled as she said in answer:

“O Folk-wolf, heed and hearken; for when shall thy life be spent

And the Folk wherein thou dwellest with thy death be well content?

Whenso folk need the fire, do they hew the apple-tree,

And burn the Mother of Blossom and the fruit that is to be?

Or me wilt thou bid to thy grave-mound because thy battle-wrath

May nothing more be bridled than the whirl wind on his path?

So hearken and do my bidding, for the hauberk shalt thou bear

E’en when the other warriors cast off their battle-gear.

So come thou, come unwounded from the war-field of the south,

And sit with me in the beech-wood, and kiss me, eyes and mouth.”

And she kissed him in very deed, and made much of him, and fawned on him, and laid her hand on his breast, and he was soft and blithe with her, but at last he laughed and said:

“God’s Daughter, long hast thou lived, and many a matter seen,

And men full often grieving for the deed that might have been;

But here my heart thou wheedlest as a maid of tender years

When first in the arms of her darling the horn of war she hears.

Thou knowest the axe to be heavy, and the sword, how keen it is;

But that Doom of which thou hast spoken, wilt thou not tell of this,

God’s Daughter, how it sheareth, and how it breaketh through

Each wall that the warrior buildeth, yea all deeds that he may do?

What might in the hammer’s leavings, in the fire’s thrall shall abide

To turn that Folks’ o’erwhelmer from the fated warrior’s side?”

Then she laughed in her turn, and loudly; but so sweetly that the sound of her voice mingled with the first song of a newly awakened wood-thrush sitting on a rowan twig on the edge of the Wood-lawn. But she said:

“Yea, I that am God’s Daughter may tell thee never a whit

From what land cometh the hauberk nor what smith smithied it,

That thou shalt wear in the handplay from the first stroke to the last;

But this thereof I tell thee, that it holdeth firm and fast

The life of the body it lappeth, if the gift of the Godfolk it be.

Lo this is the yoke-mate of doom, and the gift of me unto thee.”

Then she leaned down from the stone whereon they sat, and her hand was in the dewy grass for a little, and then it lifted up a dark grey rippling coat of rings; and she straightened herself in the seat again, and laid that hauberk on the knees of Thiodolf, and he put his hand to it, and turned it about, while he pondered long: then at last he said:

“What evil thing abideth with this warder of the strife,

This burg and treasure chamber for the hoarding of my life?

For this is the work of the dwarfs, and no kindly kin of the earth;

And all we fear the dwarf-kin and their anger and sorrow and mirth.”

She cast her arms about him and fondled him, and her voice grew sweeter than the voice of any mortal thing as she answered:

“No ill for thee, beloved, or for me in the hauberk lies;

No sundering grief is in it, no lonely miseries.

But we shall abide together, and that new life I gave,

For a long while yet henceforward we twain its joy shall have.

Yea, if thou dost my bidding to wear my gift in the fight

No hunter of the wild-wood at the changing of the night

Shall see my shape on thy grave-mound or my tears in the morning find

With the dew of the morning mingled; nor with the evening wind

Shall my body pass the shepherd as he wandereth in the mead

And fill him with forebodings on the eve of the Wolfings’ need.

Nor the horse-herd wake in the midnight and hear my fateful cry;

Nor yet shall the Wolfing women hear words on the wind go by

As they weave and spin the night down when the House is gone to the war,

And weep for the swains they wedded and the children that they bore.

Yea do my bidding, O Folk-wolf, lest a grief of the Gods should weigh

On the ancient House of the Wolfings and my death o’ercloud its day.”

And still she clung about him, while he spake no word of yea or nay: but at the last he let himself glide wholly into her arms, and the dwarf-wrought hauberk fell from his knees and lay on the grass.

So they abode together in that wood-lawn till the twilight was long gone, and the sun arisen for some while. And when Thiodolf stepped out of the beech-wood into the broad sunshine dappled with the shadow of the leaves of the hazels moving gently in the fresh morning air, he was covered from the neck to the knee by a hauberk of rings dark and grey and gleaming, fashioned by the dwarfs of ancient days.

Chapter IV. The House Fareth to the War

––––––––

Now when Thiodolf came back to the habitations of the kindred the whole House was astir, both thrall-men and women, and free women hurrying from cot to stithy, and from stithy to hall bearing the last of the war-gear or raiment for the fighting-men. But they for their part were some standing about anigh the Man’s-door, some sitting gravely within the hall, some watching the hurry of the thralls and women from the midmost of the open space amidst of the habitations, whereon there stood yet certain wains which were belated: for the most of the wains were now standing with the oxen already yoked to them down in the meadow past the acres, encircled by a confused throng of kine and horses and thrall-folk, for thither had all the beasts for the slaughter, and the horses for the warriors been brought; and there were the horses tethered or held by the thralls; some indeed were already saddled and bridled, and on others were the thralls doing the harness.

But as for the wains of the Markmen, they were stoutly framed of ash-tree with panels of aspen, and they were broad-wheeled so that they might go over rough and smooth. They had high tilts over them well framed of willow-poles covered over with squares of black felt over-lapping like shingles; which felt they made of the rough of their fleeces, for they had many sheep. And these wains were to them for houses upon the way if need were, and therein as now were stored their meal and their war-store and after fight they would flit their wounded men in them, such as were too sorely hurt to back a horse: nor must it be hidden that whiles they looked to bring back with them the treasure of the south. Moreover the folk if they were worsted in any battle, instead of fleeing without more done, would often draw back fighting into a garth made by these wains, and guarded by some of their thralls; and there would abide the onset of those who had thrust them back in the field. And this garth they called the Wain-burg.

So now stood three of these wains aforesaid belated amidst of the habitations of the House, their yoke-beasts standing or lying down unharnessed as yet to them: but in the very midst of that place was a wain unlike to them; smaller than they but higher; square of shape as to the floor of it; built lighter than they, yet far stronger; as the warrior is stronger than the big carle and trencher-licker that loiters about the hall; and from the midst of this wain arose a mast made of a tall straight fir-tree, and thereon hung the banner of the Wolfings, wherein was wrought the image of the Wolf, but red of hue as a token of war, and with his mouth open and gaping upon the foemen. Also whereas the other wains were drawn by mere oxen, and those of divers colours, as chance would have it, the wain of the banner was drawn by ten black bulls of the mightiest of the herd, deep-dewlapped, high-crested and curly-browed; and their harness was decked with gold, and so was the wain itself, and the woodwork of it painted red with vermilion. There then stood the Banner of the House of the Wolfings awaiting the departure of the warriors to the hosting.

So Thiodolf stood on the top of the bent beside that same mound wherefrom he had blown the War-horn yester-eve, and which was called the Hill of Speech, and he shaded his eyes with his hand and looked around him; and even therewith the carles fell to yoking the beasts to the belated wains, and the warriors gathered together from out of the mixed throngs, and came from the Roof and the Man’s-door and all set their faces toward the Hill of Speech.