Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Arc Publications

- Kategorie: Poesie und Drama

- Serie: Visible Poets

- Sprache: Englisch

These poems contemplate the poet's native land of Russia, while at the same time casting a jaundiced eye on the alien culture of America, where he spent the final years of his life. Whether absorbed by the world of literature (particularly his fellow poets) or relating real-life experiences, Loseff conjures up a restless, frequently disturbing universe, full of complex imagery, rich literary allusion and formal experiment. Lev Loseff was born in 1937, grew up in Leningrad and worked as a journalist in northern Sakhalin, and as a magazine editor and children's playwright. He emigrated to America in 1976, where he later taught Russian literature at Dartmouth College, New Hampshire. He died in the USA in 2009. G.S. Smith was Professor of Russian at the University of Oxford from 1986 to 2003. He translated the bilingual anthology Contemporary Russian Poetry (1993), and worked in collaboration with Lev Loseff for many years. This book is also available as an ebook: buy it from Amazon here.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 134

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2012

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

AS I SAID

Published by Arc Publications,

Nanholme Mill, Shaw Wood Road

Todmorden OL14 6DA UK

www.arcpublications.co.uk

Original poems copyright © Estate of Lev Loseff 2012

Translation copyright © G. S. Smith 2012

Introduction copyright © Barry P. Scherr 2012

Copyright in the present edition © Arc Publications 2012

Design by Tony Ward

978 1904614 83 8 (pbk)

978 1906570 11 8 (hbk)

978 1908376 44 2 (ebook)

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Earlier versions of some of these translations were published in The Dark Horse, The Oxford Magazine, Poetry Review, and The Times Literary Supplement

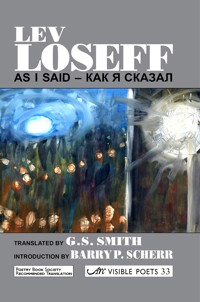

Cover painting by Marcus Ward

This book is in copyright. Subject to statutory exception and to provision of relevant collective licensing agreements, no reproduction of any part of this book may take place without the written permission of Arc Publications

Arc Publications: ‘Visible Poets’ series

Editor: Jean Boase-Beier

LEV LOSEFF

AS I SAID

КАКЯСКАЗАЛ

•

Translated by

G. S. Smith

Introduced by

Barry P. Scherr

2012

CONTENTS

Series Editor’s Note

Translator’s Preface

Introduction

В клинике

•

At the Clinic

ГОВОРЯЩИЙ ПОПУГАЙ

/

THE TALKING PARROT

Квартира

•

The Flat

Экскурсия

•

An Excursion

Казань‚ июль 1957

•

Kazan, July 1957

Школа № 1

•

School No. 1

Козлищ как не приравняешь к овцам?

•

Who Says Sheep Are Different From Goats?

Иосиф в 1965 году

•

Joseph in 1965

Депрессия-Россия

•

Russian Depression

В пустом зале

•

In the Empty Room

КАК Я СКАЗАЛ

/

AS I SAID

Замывание крови…

•

The Blood Washed Off…

Новоселье

•

The New Abode

Опять нелетная погода

•

Grounded Again

Памяти полярника

•

In Memory of a Polar Explorer

Прозрачный дом

•

The See-through House

В похоронном дому…

•

The Funeral Parlour’s Abuzz…

С. Д.

•

S. D.

Из Бунина

•

Out of Bunin

Отрывок

•

Fragment

Пирс испарился

•

The Pier that Disappeared

Под старость…

•

As You Get On…

Город живет…

•

This City’s Alive…

Сейчас

•

Right Now

SISYPHUS REDUX

Июнь 1972 года

•

June 1972

Почерк Достоевского

•

Dostoevsky’s Handwriting

Реформатор

•

The Reformer

Стоп-кадр

•

Freeze-frame

ПОСЛЕСЛОВИЕ

/

AFTERWORD

Послесловие

•

Afterword

Памяти Михаила Красильникова

•

In Memory of Mikhail Krasilnikov

Второе рождение

•

A Second Birth

Я и старая дама

•

Me and the Old Lady

Сердцебиение

•

Heartbeat

НОВЫЕ СВЕДЕНИЯ О КАРЛЕ И КЛАРЕ

/

NEW INFORMATION CONCERNING CARL AND CLARA

Нет

•

Not

Без названия

•

Untitled

Ветхая осень

•

Old Testament Autumn

В альбом О.

•

For O’s Scrapbook

Забытые деревни

•

Forgotten Villages

Джентрификация

•

Gentrification

Парижская нота

•

The Parisian Note

Подражание

•

Imitation

С грехом пополам

•

There but for…

ТАЙНЫЙ СОВЕТНИК

/

PRIVY COUNCILLOR

Апрель 1950

•

April 1950

Туалет

•

Toilette

В гроссбух

•

Ledger Entry

Декабрьские дикие сны

•

December Dreams Come in a Crazy Rush

Разбужен неожиданной тишиной

•

Awakened by an Unexpected Silence

ЧУДЕСНЫЙ ДЕСАНТ

/

THE MIRACULOUS RAID

Местоимения

•

Pronouns

Трамвай

•

The Tram

Живу в Америке от скуки

•

I’m Living in the States From Boredom

Тем и прекрасны эти сны

•

The splendid thing about these dreams

Земную жизнь пройдя до середины

•

Having traversed half my three score and ten

Сонет

•

Sonnet

Продленный день…

•

The Extended Day…

Нелетная погода

•

Grounded

Последний романс

•

The Last Romance

Он говорил: ‹А это базилик›

•

‘And this one here is basil’, he declared

Notes to the English TextsBiographical Notes

SERIES EDITOR’S NOTE

The ‘Visible Poets’ series was established in 2000, and set out to challenge the view that translated poetry could or should be read without regard to the process of translation it had undergone. Since then, things have moved on. Today there is more translated poetry available and more debate on its nature, its status, and its relation to its original. We know that translated poetry is neither English poetry that has mysteriously arisen from a hidden foreign source, nor is it foreign poetry that has silently rewritten itself in English. We are more aware that translation lies at the heart of all our cultural exchange; without it, we must remain artistically and intellectually insular.

One of the aims of the series was, and still is, to enrich our poetry with the very best work that has appeared elsewhere in the world. And the poetry-reading public is now more aware than it was at the start of this century that translation cannot simply be done by anyone with two languages. The translation of poetry is a creative act, and translated poetry stands or falls on the strength of the poet-translator’s art. For this reason ‘Visible Poets’ publishes only the work of the best translators, and gives each of them space, in a Preface, to talk about the trials and pleasures of their work.

From the start, ‘Visible Poets’ books have been bilingual. Many readers will not speak the languages of the original poetry but they, too, are invited to compare the look and shape of the English poems with the originals. Those who can are encouraged to read both. Translation and original are presented side-by-side because translations do not displace the originals; they shed new light on them and are in turn themselves illuminated by the presence of their source poems. By drawing the readers’ attention to the act of translation itself, it is the aim of these books to make the work of both the original poets and their translators more visible.

Jean Boase-Beier

TRANSLATOR’S PREFACE

The translations in this book are authorised, which needs some explanation. The most familiar use of the word occurs, of course, in connection with the King James Bible, and is intended as a minatory indication of doctrinal correctness: the authorities are stating that this is the translation, and the faithful must spurn all others. It goes without saying that I intend nothing of this sort; in fact, I hope that among other things the appearance of these versions of Lev Loseff’s poetry will encourage other translators to tackle it. What I wish to convey is the main fact about these translations that for me makes them different from any other verse texts I have undertaken: they were developed in consultation with the author and were granted his approval.

In the present state of copyright law as I understand it, one may not simply go ahead and publish translations of the work of a living author without that author’s permission, and in this sense all legal translations are authorised. Concerning the translations in this book I am speaking about something more than this kind of permission. Most living authors or their agents, I would guess, grateful for the attention and the possible proceeds, freely grant permission for translation and do not vet the results; apart from anything else, they probably lack the linguistic competence to make a well-founded judgement. In this respect Loseff was different, in fact perhaps in a class of his own. Of all the literary Russians I have encountered in over forty years of professional activity in the field, he had the most profound and subtle knowledge of English, and so his comments carried weight.

I say this in full awareness – an unavoidable and even forbidding awareness – of the poet who not so long ago radically changed the situation with regard to the translation of Russian poetry into English. Joseph Brodsky happened to be one of Loseff’s closest friends, and Loseff wrote both a biography of him and extensive annotations for the most authoritative Russian edition of his poetry. In these writings, he on the whole avoided analysing the linguistic aspect of the work Brodsky wrote in English, translated and original, for the good reason that his priorities lay elsewhere – in the centrally important questions of the life and primary writings of his subject. The work of what is by now a substantial number of scholars has shown, though, that Brodsky wished increasingly to control the translation of his work into English. The translated texts of his poems begin by being attributed unambiguously to someone else, then comes a period when they are attributed to Brodsky jointly with a collaborator, and eventually we find what some people have called auto-translations, with Brodsky credited as both author and translator. I am inclined to think that these latter texts belong to a specific genre that merits analysis separately from translations made by more familiar methods; whatever be the case, they are ‘authorised’ in a much stricter sense than the way I wish to imply with regard to my version of Loseff.

Brodsky used to insist that his Russian poetry be translated into an English that reflects the verse form of the original. I say this as the grateful one-time recipient of his permission to break this rule. When I put together my bilingual anthology Contemporary Russian Poetry in the late 1980s, the model I had in mind was Dimitri Obolensky’s Penguin Book of Russian Verse (1962), the book from which I and my generation of Russianists gained our basic knowledge of the subject. My anthology was eventually published in 1993, and gratefully dedicated to Obolensky. The prose translations in that Penguin reader, appended at the bottom of the page according to the standard format for the series in which it appeared, were apart from anything else a treasure trove for Anglophone students of Russian. I wanted to pursue the same pedagogical objective in my anthology, though I preferred en-face translations that mirrored the line divisions of the original. I asked Brodsky for permission to print this kind of translation of the ten poems of his I had chosen, arguing that the anthology would simply be invalid without his presence, but also that a deviation from the standard format would seriously damage the integrity of the book; and he gave permission for my versions without challenging my selection or demanding to vet the results.

My first substantial batch of translations of Lev Loseff’s poetry was made for this same anthology. In a survey article of 1987 that outlined the situation in Russian poetry my anthology later tried to represent, I published a couple of metrical translations of poems by him, and the following year I published an article entirely devoted to his work. I then set about the translations for my anthology, consulting the author as I went. I still have the earliest drafts I sent Loseff, returned with extensive but crisp annotations in his precise handwriting. Not for nothing was he at one time a professional editor, on the Leningrad journal Kostër (The Campfire), and later at Ardis publishers, where he edited two of Brodsky’s major collections. I realised then that not only did he possess an extraordinarily nuanced comprehension of my sometimes excessively colloquial English English, but also was capable of explicating his own work to an extent I had not encountered before among Russian poets. Even more, he was willing to do so, and to an outsider to boot, without retreating into obscurantism or protestations of professional tradecraft. I was not surprised by this capacity; it went hand in hand with the exceptionally high intellectual level of Loseff’s poetry and also his self-deprecating attitudes. One respect in which Loseff repeatedly drew a line and preferred not to explicate, though, was in the matter of annotation. At my request, he provided the notes appended to the English texts below, but he was unwilling to have some cryptic references explained, for example certain initials, preferring not to make the text so specific, and more generally not to spoonfeed the reader; and I have perforce respected his preferences.

One very important respect in which the present text is not authorised in the familiar sense concerns the choice of texts for translation. This choice has been entirely mine, and not surprisingly I have gone for those poems that seemed to me to work well in English. Lev Loseff did not offer very many comments on my choices, and several years ago he declined my invitation to draw up a list of what would seem to him essential if the selection were to be representative according to his own view of his work. I became convinced after many vain attempts that a substantial proportion of what he wrote defies adequate translation, or at least defies my capacity for it. Even though I believe that in principle everything and anything can be translated if the right method can be found, I challenge anyone to English those supremely witty poems by Loseff where Russian wordplay is both the principal device and the subject matter, functioning as both form and content. Just one such is ‘Son o iunosti’ (‘Dreaming about my Youth’) from the collection Posleslovie (Afterword, 1998), where Loseff makes hilarious and simultaneously poignant common nouns out of the names of his youthful pals. Faced with lacunae such as this, all I can do is offer an impression of how much is here and how much has been omitted: I would guess that in all, this book offers versions of about a quarter of the total original œuvre. The reverse chronological order by published collection adopted in this book, though, unlike the selection of poems, reflects the author’s strongly declared preference, which I never felt entitled to question.

One of the poems I chose for my 1993 anthology was Loseff’s characteristically wry account of his experience as a professional editor in Russia. My painful awareness of the elegance and packed economy that was lost from his metrical Russian in my prose version was the most powerful stimulus for my attempts to make translations in verse. Elegance is one thing, economy another; or perhaps not, when translation is the subject. In speaking about these qualities, though, the spectre arises of the most unavoidable and intractable problem faced by translators of Russian poetry: formal equivalence, and the entailed pressure to add to or subtract from the original. Even highly sophisticated Russians in my experience tend to believe that broadly speaking, Western poetry, and poetry in English in particular, has abandoned strict form, whereas their own has remained true to it and is better off as a result. In my opinion this belief both seriously underestimates the persistence and perceived validity of strict form in English, and equally seriously misunderstands the dynamic nature of the Russian treatment of it. To refer to Russian metrical practice as ‘traditional’ (or even worse, ‘conservative’ or ‘classical’) is woefully misleading. For Russian poets writing in the early twenty-first century it is in no sense odd or archaic to believe, for example, that iambic and trochaic metres are palpably different in their semantic and stylistic associations, and so on across the entire repertoire of metrical resources, including rhyme. And so the translator constantly needs to weigh how best to proceed in representing this repertoire, one that has indeed been largely eroded in front-line poetry in English over the last hundred years. This problem is particularly important for the translator of Loseff, who has a virtuoso command of the entire spectrum of received metrical forms (and has added a few of his own) in addition to an extraordinarily acute understanding of their historical resonances.