Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

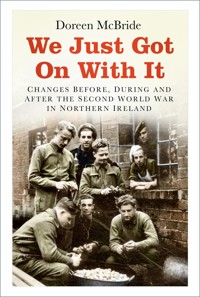

- Herausgeber: THP Ireland

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

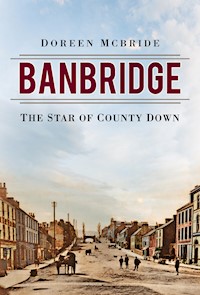

Banbridge gets its name from the bridge built across the River Bann in 1712. It's a thriving modern town, rife with history and culture, surrounded by beautiful scenery that provided an iconic location for the internationally acclaimed television series Game of Thrones. It's the setting of the well-known folk song 'The Star of the County Down', contains Europe's first flyover bridge and an ancient church founded by St Patrick himself. Travel from Ballievey along the Lower Bann, discover ancient Celtic sites, the remains of old linen mills and a Second World War aeroplane factory. Look, too, for the famous names attached to Banbridge, including Ernest Walton, the first person to see an artificially split atom; F.E. McWilliam, the renowned sculptor; and Captain Francis Crozier, the explorer who discovered the North West Passage.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 267

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2020

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Front cover image: The Cut, c.1900

Back cover image: Weir on River Bann

First published 2020

The History Press

97 St George’s Place, Cheltenham,

Gloucestershire, GL50 3QB

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

© Doreen McBride, 2020

Illustrations © Doreen McBride

The right of Doreen McBride to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without the permission in writing from the Publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 0 7509 9553 5

Typesetting and origination by The History Press

Printed in Great Britain

eBook converted by Geethik Technologies

CONTENTS

Introduction

Acknowledgements

1 The Old Places, the Celts and Fairies

2 Transport

3 The Churches

4 Life in the Past

5 Emigration, the Great Famine and the Workhouse

6 Folklore and Folk Cures

7 Industry

8 Banbridge at War

9 Education and Literary Connections

10 Calendar Customs

11 Townlands around Banbridge

12 Chronology of Events

Appendix

Bibliography

INTRODUCTION

Banbridge is set in an ancient landscape that contains remnants of our ‘Celtic’ heritage, although the town itself is a planter town founded by Moyses Hill (sometimes written Moses Hill), who was a soldier in the Elizabethan wars (1693–03).

Elizabeth I’s army was led by Sir Arthur Chichester, who came from Devon, and Moses Hill was his chief lieutenant. He, like Sir Arthur, was awarded land as a reward for his services to the queen. In the early 1600s he built a small tower house at Whitehead, which he named Castle Chichester after his commanding officer. Over time he acquired more land and built fortified houses at Malone, Stranmillis and Hillhall. At one time the Hill family boasted that they could travel from one end of Ireland to another without putting a foot on land belonging to anyone else!

The Hills were eventually awarded the title Marquess of Downshire. They settled in Hillsborough, owned the land around Banbridge and were responsible for the town’s layout. The oral tradition states they were good landlords, who lived in Ireland and cared for their tenants.

Hillsborough Castle has recently been designated as one of the Royal Palaces, and is open to the public. Hillsborough itself in a Georgian town and the Georgian influence is evident in the older houses in Banbridge.

I was born and brought up in Belfast. Moving to Banbridge in 1975 was, I thought, like going to the ends of the earth! I quickly settled in and found I was living among warm, friendly, helpful, generous people, who are rightly proud of their town, the achievements of its citizens and the surrounding beautiful countryside. I was, and still am, stunned by its literary connections, its contribution to education, the efforts made during both world wars, the heritage of its linen industry and the generosity of its citizens.

I would never have guessed that one of the first two people to split the atom, Ernest Walton, went to school in Banbridge, as did F. E. McWilliam, the son of a local doctor and a sculptor with an international reputation. Who’d have thought the man who discovered the Northwest Passage around the top of Canada, Captain Crozier, was born in Church Square? His old home is opposite a statue erected to commemorate his achievement and the house is marked by a blue plaque.

Daniel Radcliffe’s (Harry Potter’s) grandfather had a bakery in Dromore Street and made my next-door neighbour, Margaret Graham’s, wedding cake!

All this leads to the question: would I go back to live in Belfast? Belfast is a beautiful city, I enjoyed living there and the big smoke does have certain attractions, but no way am I going back there to live! I have grown to love Banbridge and its people, and have done what Walter McCabe, the estate agent from McCabe and Baird, said most blow-ins do, namely buy a grave! They have no intention of leaving until their time on earth is up and neither have I!

Banbridge is a dead-on wee town.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I always enjoy writing acknowledgements because it makes me remember all the lovely helpful people I have met on the way and the fun I’ve had. First of all I’d like to thank my husband, George, who inspired me to write about Banbridge when he said, ‘Why don’t you write about your own home town? I know you’d be safe there and I wouldn’t have to trail around behind you making sure you don’t get into trouble.’ (George believes when I do research and ask what he calls ‘innocent strangers’ questions, I’ll be picked up by the police, who could think I was soliciting, or be taken to the nearest lunatic asylum, or simply be attacked!) I thought, ‘Why not?’ Banbridge is a fascinating place with a long history.

I’d also like to thank my cousin, Vernon Finlay, who read my manuscript and made very helpful, constructive, honest comments and suggestions. His help is invaluable and I am very grateful.

I am also grateful to Dr Gavin Hughes, Director or Irish Conflict Archaeology Network at the Centre for Medieval & Renaissance Studies Trinity College, for information about raths and the people who lived in them; the late Dr Bill Crawford; Dr Linda Ballard; Dr J.P. Mallory; the late Dr George Otto Simms, former Church of Ireland Primate and world-renowned expert on the Book of Kells; Anne McMaster and, of course, the staff of the Linen Hall Library, Newry Library, Banbridge Library, the Irish Library in Armagh and the Newspaper Library; Plunkett Campbell, for information on the linen industry; Florence and Ken Chambers, for information on agriculture; and the then principal Stephen Wilson and vice-principals Kate Orr and Tom Moore of Edenderry Primary School, who collected local folklore and cures. I am also indebted to the late Stanley Mackey; the late Francie Shaw; the late Dr Cahal Dallat; Ella Brown; Margaret Jones; Tom Topping for information about Down Shoes (also known as the Lotus Factory); my neighbours Margaret and Billy Graham, who are a mine of information; and to my editors at The History Press, Nicola Guy and Ele Craker, who are a kindly source of information and encouragement.

Last but not least, thanks are due to Dessie Quail, who gave me access to his wonderful collection of old photographs.

1

THE OLD PLACES, THE CELTS AND FAIRIES

I could not have written this chapter without the generous help given by Dr Gavin Hughes, Director of the Irish Conflict Archaeology Network, Centre for Medieval & Renaissance Studies Trinity College. He was very generous with his expertise, attempted to keep my feet on the ground because my head is full of folklore, and provided me with the appendix. I wouldn’t have known to look for it!

‘The Old Places’ in folklore may be defined as prehistoric monuments such as court graves, dolmens, ancient raths and forts. They are left by those called by the generic name ‘The Celts’, and their mark still exists around Banbridge.

The Celts were an aggressive people who frequently went cattle raiding. They had a highly organised society with sensible, environmentally friendly rules, such as you must not fell a tree without permission. Rules were enforced by the Druids (spiritual advisers, wizards). They made outstanding gold jewellery and the courts of the Celtic kings abounded with musicians, storytellers and bards who wrote wonderful poetry. Some of those poems and stories, such as ‘The Ulster Cycle of Tales’ and ‘The Children of Lir’, have survived. They were passed on through the oral tradition.

Banbridge has its own storytelling tradition. Patrick Brontë, the father of the famous Brontë sisters, was born near Banbridge. Helen Waddell had strong local links and is buried in the family grave in Magherally Churchyard.

While storytelling in America I developed close contact with the Lenni Lenape (Native Americans from the Delaware Valley) and discovered similarities to Celtic culture. Both peoples put great emphasis on preserving the earth and believe that everything that lives should return to earth. I took my good friend, Carla Messinger, chief of the Lenni Lenape, to see the late local historian Dr Cahal Dallat, who was fascinated to find similarities between Gallic and Carla’s native language, Lenapé Unami Delaware, an Algonquian language!

When Christianity arrived in Ireland, the existing Celtic artistic expertise enabled wonderful manuscripts, such as the Book of Kells, to be produced.

At one time Ireland had more than 200 kings. The ceremony to crown a king was very different from what happens today. A fire was lit and used to heat rocks until they were red hot. A large hole was dug near a water supply so water could seep into it and it could be used as a ‘cooking pot’. The water was heated by manoeuvring the red hot rocks into it. The whole scene was one of jovial merriment as people danced and sang as they worked, to music provided by a fiddler.

When the ‘cooking pot’ was ready, the naked king-to-be ran towards it leading a white horse, which was slaughtered, its body segments wrapped in straw and placed into the ‘pot’. The Celts normally ate pork so horse flesh was regarded as a special treat. When the horse was cooked it was removed and the water left behind in the ‘pot’ was cooled by the addition of fresh water to prepare it as a ‘bath’. The naked king jumped into the bath and quaffed its waters using a drinking cup formed from a cow’s horn. Having drunk his fill, he refilled the cup and passed it around the crowd so that everyone had a share, and after that they regarded him as their king.

According to folklore, it’s very dangerous to go near the old places after dark because the fairies live there and they might steal you! Irish fairies are large, ugly individuals about the size of a child somewhere between 2 and 6 years of age. They are not the tiny, pretty, creatures, such as Tinkerbell, depicted in children’s books.

Local people say they don’t believe in fairies but very few would risk interfering with a fairy thorn and neither would I! Strange things happen! In the 1970s the owners of what was then Supervalu wanted to enlarge their car park, behind their premises in Newry Street. That entailed removing a fairy thorn. They had great difficulty in getting any workman to agree to do so until a man came from Rathfriland, said he didn’t believe in fairies and chopped the tree down. He had a lot of experience felling trees, but that fairy thorn appeared bewitched. It twisted as it fell and broke his arm.

The countryside around Banbridge abounds in fairy thorns. There’s a very obvious one on the left-hand side of the main road when travelling from Banbridge towards Castlewellan. It’s set back from the road in a field that usually contains sheep. The sheep were eroding the soil under it so the owner built a raised protective ring of rocks around it.

Fairies were believed to live underground in souterrains, which usually date from the early Christian period. They were underground caverns with a well-concealed entrance leading to a narrow tunnel. They were built for protection and were easy to defend! Unwanted people crawling out of the tunnel into the cavern were knocked unconscious as they stuck their heads into the opening.

Smugglers used souterrains to conceal contraband. It would have been to their benefit to ‘disappear’ people, blame the fairies and be left in peace to carry on their illegal trade.

In the past people had what we today would consider a peculiar attitude to misfortune. They believed if something awful happened to a family, or to an individual, it was because a terrible sin had been committed and God was meting out punishment. That belief affected everybody, from the poorest peasant to the wealthiest, including Queen Victoria. She had a son, Prince John, who was educationally challenged so he was kept hidden. It would never have done if her subjects thought their high and mighty queen had done something so wrong that God felt it necessary to punish her by giving her a disabled child! Other parents wanting to hide a disabled child may have hidden it, or them, in a souterrain. That would explain why perfectly sensible folk reported music coming from under the ground.

Fairies were thought to steal human babies and leave a fairy baby, called a changeling, instead – and that could lead to tragedy, as shown by my Granny Henry’s experience. Granny once employed a young girl, Maud Brown, who started life by being thought of as a changeling. She was born in the early 1900s near Hannahstown, which at that time was a village close to Belfast. It has since then been incorporated within the city and lies at the foot of Divis Mountain.

Maud was an achondroplastic dwarf. (Achondroplasia is a genetic disease that causes the sufferer’s arms and legs to be abnormally short. The defect is obvious at birth.) People believed if they gave a changeling back to the fairies there was a good chance the original baby would be returned. Maud’s mother thought she was a changeling because of her ‘odd’ appearance, and left Maud beside a nearby fairy fort.

Poor Maud’s pitiful cries were heard by a Presbyterian minister, who picked her up and carried her to the local orphanage at Ballysillan, where she was raised.

My grandmother, Elizabeth Henry, ran a very successful shop in Morpeth Street off Belfast’s Shankill Road. She was very busy housekeeping and organising her business. She decided to visit Ballysillan orphanage to look for a suitable young girl to help her, and she met Maud.

Granny said, ‘There was something about Maud. I looked at her and thought, “That child will be next to useless as far as I’m concerned. She’s so small she won’t be able to lift things down from high shelves. I really need somebody taller.” But then I looked at Maud and thought, “I like her. If I don’t give her a job nobody else will because there’ll be so much she won’t be able to do.”’

Granny was a kindly woman. She took Maud home and Maud became like a daughter to her.

In the past people believed boys were more likely to be stolen than girls. That’s why all babies were dressed like girls until they were about 2 years of age. The only way to tell the difference was that boys wore laced up boots while girls’ shoes were held on by a strap closed by a button.

Raths around Banbridge were used by farming families, mostly as defended animal pens but sometimes as fortified farmsteads. They date from the early Christian period and were used until well into medieval times. They consisted of an inner central circle, which contained a dwelling occupied by the family, and an outer circle in which the animals were kept. Each circle was surround by a circular protective palisade fence.

The central dwelling was usually made of woven branches found locally and thatched with local materials such as heather, whins (also known as gorse and furze) or grass. Sometimes it was made of stones and mud. It had a hole in the roof to allow smoke from the central fire to escape. A cooking pot was suspended from a tripod over the fire for cooking. Women’s eyes became red and inflamed from attending it, as being constantly exposed to wood smoke is unhealthy because it is carcinogenic. People could either have slept in a circle around the fire with their feet pointing towards it (they had to be careful not to move too far down the ‘bed’ to keep their feet from being burnt) or on a woven structure situated against the exterior wall.

Some of the remains of raths excavated showed a surprising degree of sophistication. They had cavity wall insulation, with an inner and an outer wall and the space between them filled with heather.

People living in a rath were self-sufficient. They grew their own food along with a little flax to make clothes, and fertilised their crops using manure produced by their animals, dealing with their own excrement by digging a latrine.

Unfortunately the majority of raths around Banbridge have been destroyed by the activity of farmers. The only sign that remains of the one I live on is that the land inside my property is much higher than the road and sometimes I find ancient tools when I’m gardening. Slightly further up the road is an old farmstead, The Hill, which is probably part of the same rath. It still has a well, an important attribute of an ancient dwelling because water is essential for life.

More obvious remains of a rath are found on the left side of the road when travelling from Banbridge to Castlewellan. It is situated above the new Ballydown Primary School and next to the old school. The staff say it’s a great place to take children for storytelling!

Sometimes local superstitions associated with a rath are all that is left. The one that was on the Newry Road has completely disappeared except for the fact that elderly local people think of the road as the Yellow Hill. Yellow is a colour associated with the fairies.

The raths themselves are not the only thing to have been vandalised. The Ordnance Survey Memoirs of Ireland, Parishes of County Down III 1833–8, Vol. 12 tells of a boat or canoe, hewn out of an oak tree, that was found in Ballylough swamp in 1826. It was 42ft long, 3ft wide and 3ft deep and was cut up for firewood!

Lisnagade Ring Fort, on the outskirts of Banbridge, is the best preserved local rath. It is situated 3 miles from Banbridge on the Banbridge/Scarva Road, a short distance from the main road, up the Lisnagade Road. It is a large ring fort, thought to have been constructed about ad 350. It consists of three concentric earthen rings 6ft in height.

2

TRANSPORT

The area known as Seapatrick, now inside Banbridge’s boundary, is situated near an ancient road. Originally it was called Suidhe-Padruic. Suidhe means a seat or resting place. The spellings of place names change over time, so in the Magennis Patent (1610) it is Sipatrick, in the map of Down (Harriss) (1743) it is Sea-Patrick and in Williamson’s map of Down (1810) it is the same as today, Seapatrick.

Seapatrick contains the townland of Kilpike (meaning church in the wood of the pike). According to oral history, the church at Seapatrick was founded by St Patrick during the fifth century and a bell has been rung on the site every Sunday, except during times of war, since then. The houses that have been built on the site beside the church have a restriction written into their leases ensuring their owners cannot complain and cause the church bell to fall silent.

St Patrick’s church was very different from the whitewashed one on the site today. The original church would have been a small wooden structure resembling an upturned boat.

Tradition states that St Patrick travelled, by foot, from his monastery at Bangor to Downpatrick and on to Armagh, now the ecclesiastical centre of Ireland. He usually walked from Bangor to Castlewellan, Hilltown, Newry and finally Armagh. Sometimes he came across the hills from Castlewellan and used Seapatrick as a convenient stopping place. It was near, but not at, the ancient ford on the Old Kings Road that crossed the River Bann at Ballykeel.

The Kings Road was crossed by the road that leads to Tullylish, an ancient monastic site. Being near crossroads made Seapatrick convenient, and the fact it was not at them meant it was less likely to be disturbed by unwanted intruders.

The River Bann was an excellent water supply and the site had a well, which disappeared. The oral tradition concerning its existence was so strong that local historian, the late Horace Rae, decided to find it. He hired a water diviner, who found the well, and it was excavated. Unfortunately Health and Safety believed somebody might drown in it so it was quickly covered up again! At present there’s a traditional type of structure built over and around the old well to mark its position.

Two hundred years ago the only method of transport was by what was referred to as ‘Shanks’s pony’ (walking), or on horseback, by horse and cart or by coach. Most people couldn’t afford a horse so they never went more than a few miles from where they lived.

Banbridge itself is a planter town, originally called Ballyvalley. (The name is preserved in Ballyvalley Heights, a housing estate off the Dromore Road.) It was part of the 40,000-acre estate given to Moyses Hill, by Queen Elizabeth I. He came over with her army in 1553 to suppress the rebellious Irish and later acquired more land, including that around Banbridge. One of his descendants, Wills Hill, was awarded the title of Marquess in 1789.

The remains of an ancient road, King’s Road, mentioned previously, that stretched from the south to the north of Ireland, runs along the side of Hayes’s Park, on the Lurgan Road. (Hayes’s Park is signposted on the left of the road travelling from Banbridge towards Craigavon.) It’s difficult to believe the rough track was once part of a major highway.

Bell, Seapatrick Church, the ‘Wee Church‘.

A narrow footbridge crosses the Bann near the ancient ford at Ballykeel (meaning narrow town) and is where the town of Banbridge had its beginnings.

A sign on the northern side of the footbridge shows Ballykeel is where King William III and his army crossed the Bann in June 1690 en route to the Battle of the Boyne. He must have used the ancient ford because archaeological excavation failed to find remnants of a bridge of the correct age. It’s usually possible to make out the old ford by looking downstream. The river looks shallow and comparatively easy to cross.

It makes sense to think of an army crossing a river via a ford rather than over a bridge because the soldiers, all 30,000 of them, would have been able to spread out, which was quicker than marching over a narrow bridge.

A wider bridge, known as the ‘water bridge’, was erected upstream in 1712 and the town’s name changed from Ballyvalley to Bann Bridge, which, through time, has been shortened to Banbridge. The focus of the town changed and coaches no longer travelled down Kiln Lane to cross the Bann. A new road was developed down past the top of Kiln Lane, through the townland of Ballymoney and down Ballymoney Hill (townland name Edenderry (Eudab-doire, ‘The Hill Brow of the Oak Tree’). They turned left at the bottom of the hill and travelled along the short distance of the Dromore Road to the Water Bridge.

Members of Banbridge Historical Society traced the Old Coach Road back from the town and found it did pass up Ballymoney Hill (off the Dromore Road to the north of the town), travelled along Ballymoney Road then turned down Skelton’s Town Road towards the A1 dual carriageway.

Towards the end of Skelton’s Road there is a track that runs behind Tullyhinan House, a beautiful Georgian house facing the A1. (It’s difficult to see because it is partially hidden by trees.) Members of the Historical Society walked along it and found they were at the back door of Tullyhinan House, built for the Lindsay family, who arrived with the army of General Munro in the 1640s and settled at Tullyhinan (also spelt Tullyhenan). The present owners said, ‘Our house was very different in the 1600s. It was a simple white cottage then. King William tethered his horse in our stables. Come on and we’ll show you.’

King William’s army, unlike other armies that invaded Ireland, did not lay waste to the land. He bought provisions from locals to feed his army. He bought £300 worth of cattle from the Lindsay family!

The old stables, and the loft above used for storage, are still there, unchanged since the time of King William of Orange.

In 1733 an Act of the Irish Parliament (during the reign of King George II) was passed ‘for repairing the road leading from Dundalk to the Bridge over the River Bann, commonly called Bannbridge’. (Note the spelling). This Act enabled a board of trustees to be appointed for ‘better surveying, amending and keeping in repair the said highway or road’. Power was conferred to erect turnpikes and to ‘take toll’.

The Ordnance Survey Memoirs of Ireland, 1833–8, Vol. 12 states:

The high road from Dublin to Belfast, which is a turnpike road, passes through the town of Banbridge. This and the road from Castlewellan to Lurgan, running in a parallel direction with the River Bann, are the best and principal ones. Beside these, the country is intersected throughout with lanes but invariably laid out without judgement.

Today the main road from Dublin to Belfast is the A1, which has been diverted around the town. The road from Castlewellan to Lurgan still runs parallel to the River Bann. Incidentally, it was on the outskirts of Banbridge, at Ballievey and in the surrounding countryside, that some of the hit television programme Game of Thrones was shot (see Chapter 7).

The stable door behind which King William’s horse was stabled.

Parts of ancient roadways are still in existence. They may be found in loops beside modern roads and motorways, running beside them and sometimes behind houses or through fields. Occasionally they look practically unchanged, like the track that runs alongside Hayes Park. They may be traced through oral history, for example when I bought my present house on Ballymoney Hill my neighbours told me it was on the Old Coach Road that ends up in Belfast.

Mail coaches were introduced into Ireland during the eighteenth century. The Old Kings Road developed into the Old Coach Road, in much the same way that roads today are changed when they are turned into motorways.

The horses pulling the mail coaches, carts and carriages of the gentry became thirsty so horse troughs, usually with a pump beside them, were placed about 12 miles apart along roads. They’ve disappeared in Banbridge but Loughbrickland, 2 miles south of Banbridge, has taken old horse troughs and used them as containers for flowers, while a pump is used as an ornamental feature in a garden.

Coach roads kept to high ground as much as possible because that made it easier to spot highwaymen. People travelling along the old roads in counties Down and Armagh were in danger of being robbed by the highwayman Redmond O’Hanlon (c.1620–81), Ireland’s equivalent to Robin Hood. Many people were dissatisfied with the government, so he was helped by all sorts of people – protestant landlords, the militia, Catholic priests, protestant clergymen – who gave him information about potential victims.

O’Hanlon was born in Poyntzpass (a village near Banbridge), the son of a Gallic nobleman. He was angry because his family, the rightful heirs of Tandragee Castle, were dispossessed of their lands in 1652, under The Act of Settlement for the Settlement of Ireland. As a result he became a highwayman and a protector of the poor, who loved him because he kept them from starving. He organised a system of paying protection money and it was said if you paid up you could leave your doors wide open and nobody would dare to rob you. The amount he collected was greater than the king’s revenues!

Redmond O’Hanlon was such a successful highwayman the government put 100 guineas on his head, a huge amount of money in those days.

Although he was protected, he became so fearful for his life he hired two bodyguards. That was a mistake because on 25 April 1681, while the highwayman slept in a cottage at Eight Mile Bridge near Hilltown, one of his guards (a trusted relative, who was his foster brother and a member of his bunch of brigands) Art McCall O’Hanlon, shot him in the head and claimed the reward. O’Hanlon received the money and a pardon for his misdeeds and William Lucas, the member of the militia who had recruited him, was promoted to the rank of lieutenant in the British Army.

The custom of the time was to drape body parts of famous outlaws around the countryside, so pieces of Redmond O’Hanlon’s body, including his head, were shown off in this way.

Carrying mail was dangerous, thanks to the likes of Redmond O’Hanlon. Mail coaches began travelling from Belfast to Dublin in 1788. The mail was collected, or served, from Loughbrickland. There was a post office there from at least 1670. Post-boys, mounted on horseback, rode alone and carried the mail. Postage on letters wasn’t usually prepaid; it was left to the recipients either to reject the letter or accept it and pay for it. The law changed in 1840 so after that date there was a fine on letters that were not pre-paid.

On many occasions the Government was asked to ensure the safety of coaches by employing armed guards to protect them. These requests were ignored until 27 February 1788, when there were more mail robberies than usual. The matter came to a head when a post-boy was robbed by two men between Dunleer and Drogheda. Post-bags from Banbridge, Armagh, Newry, Loughbrickland and Belfast were taken. After that it was reckoned to be more economical to employ guards than pay solicitors’ expenses associated with the loss of mail.

The Ulster Journal of Archaeology (Vol. V p. 71) has an account of early coaching days:

One of the chief scenes of organised highway robbery in the North of Ireland was the Mountain road between Newry and Dundalk, and a district called Lurgan Green. I remember the first occasion of my visiting Dublin was some time before 1820. I took my seat outside the day mail-coach, starting from Belfast at six o’clock on a fine summer morning. The coach was only allowed to carry four passengers in all, four inside and four outside, none of the latter allowed to sit behind with the mail and guards. The two guards occupied the seat at the back of the coach, each armed with a polished blunderbuss of formidable dimensions and loaded pistols in belt. At Newry the coach was joined by a number of armed dragoons (I think six), who accompanied us to Dundalk, where they exchanged for another party of dragoons, who conveyed us to Drogheda. It was a grand turn out. I had not the luck to witness a fight, but I have some recollection of the feeling while going through Lurgan Green. The authorities, sometime after, succeeded in capturing this gang of bandits, many of whom were hanged; and that part of the country has been peaceful ever since.

Belfast day mail, another four-horse coach, was established in 1816 from Belfast to Dublin. It left at a more reasonable time, 8 a.m., and was slightly slower, as it was twelve hours on the road and arrived back at 5.p.m. It stopped in Banbridge to change horses.

Scott’s began running a four-horse coach from Banbridge to Belfast in 1830. It left Banbridge daily at 6 a.m. and returned at 8 p.m. Scott’s also ran a daily one-horse service between Banbridge and Newry, leaving Banbridge at 8.30 p.m. and returning at 5.30 a.m. It was timed to take passengers, who wanted to travel to Newry, and who’d come on the Scott’s coach from Belfast. That appears to have been a popular option because ‘a second coach was sent if necessary’.

The mail coaches were pulled by four horses and they stopped at Banbridge to change these. A regular service left Banbridge every day at 9.30 p.m. and returned at 3.30 a.m.