11,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

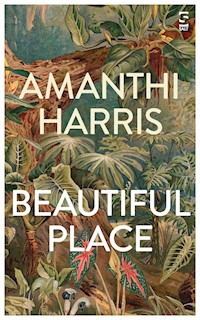

- Herausgeber: Salt

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

Beautiful Place is a novel about leaving and losing home and making family. It is about being oppressed and angry and wanting a better life – but how is a better life to be defined? The Villa Hibiscus is a house by the sea on the exquisite southern coast of Sri Lanka, home to Padma, a young Sri Lankan woman. The owner of the villa, Gerhardt, is an elderly Austrian architect to whom Padma was taken when young by her scheming father, Sunny, who had hoped to seduce the wealthy new foreigner in the area with his attractive child. Gerhardt adopts Padma and pays Sunny to stay away until she's grown up – when Gerhardt expects to have sent Padma away to University, far away. But Padma fails her exams and is lonely in the city, gladly returning to her beloved old home by the sea. With Gerhardt's help she creates a guesthouse at the villa and soon guests start to arrive, opening new vistas for Padma through their friendship and love. Then Sunny appears, ready to reclaim his daughter...

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2019

Ähnliche

BEAUTIFUL PLACE

AMANTHI HARRIS

For J and K

‘And the perfect morning, so fresh and fair, basking in the light, as though laughing at its own beauty, seemed to whisper, “Why not?”’

from ‘At the Bay’ by KATHERINE MANSFIELD

Contents

PART I

1

THROUGH THE EARLY-MORNING house Padma went out to the veranda. A breeze came in from the sea, easing in past the araliya trees. Ever since returning to the villa she’d had nightmares. In them she was always a child, alone at night in the villa’s garden, then propelled by an unseen force into a room. And it was the front room of the brothel down the lane as she had seen it one time when the black polythene over the windows flew up with the wind: plastic chairs pushed up against the walls, bottles of arrack, beer in buckets of ice. And men. There were always men. In the dream they crowded over her. She had woken up safe in her room at the villa, but the fear stayed real, fear of the sheer randomness of her luck – for it was only luck, illogical, slight, unfathomable, that had lifted her to safety. Luck didn’t make you feel lucky. Being saved didn’t make you feel safe.

A grey dawn lingered over the garden. Soon strangers would sit looking out at the sea, being at home in the villa, her world. The veranda was where all life at the villa flowed, to that view of changing waves out beyond the frangipani trees tangled around the front of the house. Already the room was altered: three new tables for guests had replaced the long old pine table now stored in the shed. The room seemed bigger. Past the trees, the sun made a red-gold rim over the sea. It burnished each ripple of the waves drawing back from the beach, simmering, settling, stilling itself after the wildness of the night. A thin yellow streak spread across the sky, growing to amber, green, turquoise – becoming the blue to come. The birds’ shrill waking cries faded and the garden came to life, filling with the quiet new brightness of morning, the new day begun.

The dog, Gustav, came out of the house and nuzzled her, wanting to be stroked. He licked her hand and went out to the porch and into the garden. He ambled contentedly around the lawn, the grass bright with dew.

“What are you doing, Baba?” Soma came up behind her, making her jump.

“You’re up early,” she said.

He had refused to wake before his usual time when the villa became a guest house – one of his many protests against her new business – but there he was, up bright and early on their first day! She smiled at him and he tried to look as if he didn’t care.

“Go and get ready. Your guest will be here and you’ll still be in your pyjamas!” he scolded.

“He’s not going to be here for ages.”

“How do you know? And you have to eat breakfast. There’s no time to make milk rice, though.”

“Oooh, milk rice! So you do think today’s auspicious?”

“I’ll make you scrambled eggs and toast, that’s all. And hot chocolate.”

“Fine!”

She stood on the porch and looked over at the lane.

“I said, get dressed!” Soma called after her.

“Later!”

She ran down the steps to the garden, alone again in the morning. But someone was coming along the lane – one of the village men, dishevelled looking after a night on the beach. He was a waiter at the Kingfisher Bar, the biggest of the beach shacks, where the backpackers lay in hammocks all day getting stoned. The man stopped outside the villa’s gate. He could see her there. Even from a distance she could see him glowering at her, see the hatred in him. The villagers all hated her more now because she was the competition. Competition! What a joke! As if any of their lowlife clientele could ever afford to stay at the villa. She looked back coldly, unsmilingly at the man – that was the way to show them you couldn’t care less what they thought of you, all the lies they made up about you and spread everywhere. Such effort it took to stay hostile, but she stared him down and he went away.

The taxi stopped at a white picket fence, an impenetrable green grown high above it. The driver didn’t help with the bags, but Rohan paid him a tip, for in the new Sri Lanka, as he had discovered, anyone could feel aggrieved at the slightest denial and respond with the true viciousness of the thwarted. He was no longer surprised by the cruelty of ordinary people, the malevolence lying in wait for release. The taxi drove away and he pulled his two suitcases behind him and went into the garden of the guest house. A dappled green shade closed over him, coconut, cashew, plantain and paw paw trees crowding in, bushes of yellow-speckled, magenta and lime-green leaves, reaching out to stroke and scratch and poke at him, examining him as he followed a path to a white-painted house up ahead. With its clay-tiled roofs and bulbous white pillars it looked like an ancient relic magnificently preserved, like his grandmother’s house of long ago on a coconut estate, but as he drew closer he saw that the villa had been far more recently built.

An Alsatian rushed onto the porch and barked down at him.

“Easy, easy, boy.” He held out his hand, backing away. “Hello! Is anyone there?” he called.

A young woman with long wet hair ran out.

“Gustav! Stop it now!” she cried and knelt beside the dog, hugging it to her with a dramatic sweep of a slender arm. “Hi there! Can I help you?” She smiled down at Rohan.

Her face was a perfect oval; a perfect face.

“I have a room booked. I telephoned last week.”

“Ah, then you must be Rohan.” She came lightly down the steps, her hand outstretched. “Welcome. I’m Padma. I’m the manager.” Very regally she shook his hand.

She was Sinhalese, he noted, the way all Sri Lankans knew about each other, but he couldn’t quite place her. There was something too cocky, too theatrical and at the same time awkward about her. She could have been the wife of the owner, a mistress, or even the maid, it was impossible to tell, there was something peculiar about her. She didn’t seem like a woman from the village – she was much too bold and outspoken. She spoke English remarkably well, although with a faint Germanic accent. He saw her smile, clearly amused by his confusion.

“Come, I’ll show you to your bungalow,” she said, still laughing at him.

She had small straight white teeth, disconcertingly even, yet natural-looking and untampered with, an easy spontaneous beauty. She looked like a woman in a Sri Lankan Airlines advertisement; the type of stewardess you never encountered unless you flew First Class or Business. She grabbed the large suitcase.

“Oof, what have you got in here? A ton of bricks?”

“I’ll take that,” he said, but she wouldn’t let him.

“I’m fine, come on!” she said, heaving it up and setting off across the garden, staggering a little.

All he could do was follow her.

“I’m a lot stronger than people think,” she said over her shoulder. “I do yoga every day. I’m almost a qualified teacher.”

Her orange and red flower-print skirt flared out over slim brown legs and her feet in red rubber slippers. She wore a silver chain with a tiny silver bell around her ankle. Her hair bounced behind her in wet glossy ringlets, swaying against the red t-shirt, her waist supplely moving with her stride. The dog trotted, a great wolf, at her side. She looked like a girl in a fairy tale. The whole place in fact was vaguely fantastical, although the exuberant wild garden, on closer inspection, showed itself to be carefully tended. She led him over a trail of circular stepping stones, flat grey bubbles, at the edge of the lawn. Crimson hibiscus flowers hung above, crinkled red lanterns, the papery petals glowing with sun, stamens bowed heavy with thick yellow pollen trembling, about to fall.

The small bungalow was at the back of the garden. Two planters chairs were set out on a veranda with carved old wooden pillars. Padma went up onto the veranda and pushed open the narrow double doors, a bolt dragging over a smooth grey cement floor, waxed and gleaming mutely in the gentle shade of daytime indoors. Something scuttled across the back of the room. The Alsatian pricked up its ears and bounded in barking.

“What was that?” Rohan demanded.

“Oh, it’s nothing!” Padma laughed nervously and grabbed a broom and charged in, thumping it under a bed shrouded in mosquito netting.

She ran to the back and crouched by a wardrobe, jabbing the broom under it. The dog howled and jumped around the room, knocking over an antique towel rail.

“Gustav! Stop it!” Padma shouted. “Stop now, you silly dog! Sit!”

Something grey and woolly whirled past Rohan and disappeared into the garden.

“There, it’s gone now,” Padma declared.

“That was a rat,” he said.

“Oh no, no, no! There are no rats in my guest house – that was a little meeya.”

“Meeya is mouse. That thing was a rat.”

“Don’t be silly! A rat is this big—” She opened out her hands.

“No, that would be a rabbit.”

She giggled. “Anyway, it’s gone now, for sure. No need to fret.”

“I want another room!”

“The other bungalow is booked – all I have is the room in the house—”

“No thank you.”

“You could try one of the other guest houses – although I’d better warn you, they’re nowhere near as nice as ours. Maybe you should go to one of the big hotels …?”

“Oh God, not a big hotel!”

“Why not?” She studied him curiously.

He ignored her. There would always be someone he knew at any one of the main hotels; people who thought they knew all about him. More whispering, more stares, more lies made up about him. He sighed.

“I’ll take the room,” he said.

“Ah, good!” She grabbed the large suitcase before he could take it, and dragged it inside.

“This is crazy heavy! What have you got in here?” she exclaimed.

He pretended not to hear.

“Huh? What’s in here? Not a dead body I hope?”

“No, not a dead body.” He held the door open for her to leave.

“What do you want for dinner?” she asked, not moving. “You need to tell me now so I can go and buy it from the market, the cook only makes things from fresh.”

“Do you have a menu?”

“Yes: fish, chicken or vegetable curry; fried rice, boiled rice or noodles.”

“Great menu.”

She looked delighted.

“I only want steamed fish with plain boiled rice and steamed vegetables. No spices,” he told her. “And what have you got for lunch?”

“The cook doesn’t make lunch for guests. He likes to sleep in the afternoons.”

“Such great service.”

“There are a few cafés up the lane,” she said blithely. “You could try the one called Boss’s Bar – he’s a friend of ours. Dinner’s in the main house at seven.”

At last she left, running out into the sunlit green, the garden claiming her back. She threw a blue rubber ball for Gustav, who raced after it over the lawn. She stood straight-backed and firm, contentedly watching the dog. She tossed back her hair, the long gleaming mass of it almost dry already. Then she went over to the main house and went inside. It was a relief to not see her anymore.

He went around the room peering into corners; under the bed, behind the wardrobe, searching for signs of rats or other vermin, but everything seemed dusted and well-swept. He gazed up into the roof beams, the roof tiles left exposed with bright slivers of sky showing in the gaps through which anything might crawl in at night and no doubt would. He thought longingly of rooms with minibars and room service and someone to complain to whenever something was not immaculate and perfectly soothing. The stillness of the bungalow pressed down on him – his first room in Sri Lanka without his family nearby – no more shocked whisperings on the other side of the door, no more prying glances when they thought he wasn’t watching.

He turned on the fan, and with that accepted he was staying at the villa. He unpacked the smaller suitcase, taking out casual clothes but leaving behind the suit and ties and shirts pristinely laundered by the dobi – with one stroke he zipped them all away. The large suitcase he kicked under the wardrobe; he never wanted to see it again. What he needed was a drink. Several. He could drink all day now if he wanted to – that at least was a consolation. Now there would be no maids or the cook keeping count for his mother as he went to the fridge. His mother and her sisters had grown convinced in the past months that he had a tendency to drink – this was how they explained what he was said to have done. They had forgotten of course that it was they who had coaxed and cajoled him on to the worst mistake he had ever made. He was on his own with that.

He looked out at the unknown garden, his new world away from them. It was not love, but the desire to be dutiful, that expectation of all good Asians, which gave others their power over you. Now he was free of them and he could do as he pleased, but he didn’t know what that was; which life to choose. What lives were there? How many had he passed by without seeing, without hearing their call? Once he had thought himself fully formed, this half-made man that he was. But how to find a new way, a way to reverse it all? How was time to be undone? He drew the curtains closed and turned back to his cool dark sheltering room.

“He’s a bit weird,” Padma told Soma in the kitchen. “Nice-looking, though.”

She tried to recall him, but she could only remember glimpses: a straight nose, an angled face, dark eyes intense and angry and so scornful as he spoke to her, yet with no hostility.

“They’re all weird in Colombo,” Soma said, filling his tobacco pouch, his fingers expertly sifting the black snarled leaves.

“He’s not from Colombo. He’s from England. There were London Heathrow stickers all over his bags.”

“As long as he doesn’t cause any trouble, I don’t mind where he’s from,” Soma said, putting the tobacco pouch into his shirt pocket with its bulge of lighter and cigarette papers and the little metal tin of marijuana she wasn’t supposed to know about.

He patted the pocket lovingly, looking ahead to being alone with its contents.

“Now about this steamed fish nonsense, what exactly am I supposed to be cooking tonight?”

“He said he didn’t like spices.”

“What sort of a sissy-boy is he? Mummy making white curry every day for him?”

“I told you, he’s not from here. He probably isn’t used to our spicy food.”

“Must be eating fish and chips and mutton stew all the time,” Soma mocked. “With pot-ay-toes and carrots. What’s the point of having a menu if they can do what they like? Next thing I’ll be making waffles and pancakes and chicken biryani with sugar-plums on top.”

Padma giggled.

“There’s nothing wrong with my fish curry,” Soma grumbled. “Who does he think he is, asking for steamed this and boiled that?”

“I think he’s used to big hotels.”

“He should go to one then.”

But the new guest had been horrified by the idea, almost afraid, like someone hunted. He had run away from somewhere, she sensed. He was at the villa trying to hide – but from whom?

“He’s here for a reason of his own,” she reflected.

“Oh I’m sure.”

“Nothing like that!” She laughed. It was impossible to imagine the moody new guest going into the house with the women.

“You can tell these things, can you?” Soma scoffed.

“I can tell a lot about people. Even Gerhardt says I have a very powerful inner eye.”

“Oh yes, your inner eye. Don’t worry, I will be keeping both of my outer eyes on him – any sign of trouble and he’s out of here.”

Soma’s efforts would come to nothing. Padma could already tell that the new guest was a different sort of straight-laced compared to the sordid business-men types who gave way to base desires when left to themselves. He was nothing like those lost, heart-dead people she’d seen wandering alone in luxury hotels when she had gone sometimes with Gerhardt on his business trips abroad. The new guest would never resort to such impoverished encounters. He was too proud, too searching. She had seen the way he looked at the garden, his gaze following a passing butterfly and lingering on a mynah bird by the pond and on the new burst of pink in the camellia bushes. He might be a poet or a novelist. The suitcase he’d made such a fuss about could have been filled with books – that would explain its weight. Or he might be a film director looking for somewhere to make a film. The villa would be the perfect place – and what publicity! The neighbours would boil with envy!

“What do you think would make a suitcase extra heavy?” she mused.

“A dead body.”

“He hasn’t got a dead body in his bag, you silly man!”

“He might do. I read in the papers just the other day about someone who came to stay in a hotel and left a suitcase behind. The hotel people thought it was a bomb so they called the police, but when they opened it, there were chopped up body parts in plastic bags. The fingers and toes were all smashed so they couldn’t check for fingerprints.”

“That guy’s not carrying a dead body around!”

“How do you know?”

“It didn’t smell. A dead body decomposes fast in the heat.”

“There are chemicals you can get to stop it stinking – but they won’t work for ever – he’ll be hoping to get rid of it fairly soon I imagine. All he’d need is to find a quiet beach … maybe that’s why he’s come here.”

“No, it’s books. Books weigh a ton. And scripts.”

“Scripts?”

“For a film. He could be looking for somewhere beautiful to make a film …”

“Ah yes, I’m sure, you know best. You’re the expert.”

He bustled smugly about the kitchen, thinking he’d had the last word. He was gathering ingredients: onions, ginger, green chillies, garlic for the daily masala; peeling, chopping. The stone pestle thumped, skins bursting, juices running, and he drew it all together into a mound and rolled it into a pale green paste on the granite slab. And then came the fizz of oil as he threw in a small wet lump of masala to fry. Soon that familiar beginning-smell, of the day’s work getting underway, drifted through the house. Soma wasn’t worried at all about the possibility of dead bodies – otherwise he’d have been rushing to ring Gerhardt.

“Now are you going to the market or not?” he asked.

“Yes, of course!”

“It’s getting late, there’ll be nothing left – do you want me to go?”

“No!”

“I don’t mind going.”

“I’m going, we agreed.”

“Then go! Quickly!”

“Okay!”

Padma put on her trainers and paused on the veranda. There was always the pause, the gathering in and steeling herself before leaving the villa. There was always the chance of a hostile encounter. One needed to be centred and strong to not let it spoil the morning.

She rearranged a spray of leaves in the vase on the dresser. Beside it was her friend Jarryd’s new book, such an elegant little volume with its mustard-yellow recycled-paper cover, and the title: Reflections on a Teardrop printed in red ink inside a single red line of border. Even the local minister with all his talk of banning the book would have admitted in private that it had style. Padma wrote on a card: ‘A guidebook to Sri Lanka by a Local Author’ and placed it next to a pile of the books. She would ensure that all of her guests bought one copy at least. They would leave her guest house knowing a little more about the country than the usual tourists, who only cared where the best beaches were for surfing and nude sunbathing and where one could buy ganja. She lifted the cover of the first book on the pile:

INTRODUCTION

Sri Lanka is a sturdy squat little house with all manner of proud impossible people living inside: Sinhalese, Tamils, Muslims, Burghers, Wanniyala-aetto (or Veddhas, as they are known derogatively by the others), all squeezed in together with nowhere to go to escape from each other, surrounded by soft sand beaches shaded by coconut palms and glistening blue seas with hidden treacherous currents – all the loveliness of Paradise encircling them in their earth-bound entrapment.

Jarryd’s book was quite different to other guidebooks. It was the Sri Lanka that Jarryd inhabited and the place he longed for it to be. His book was a cry for peace, a protest against corruption, yet Jarryd’s Sri Lanka was a place of beauty and hope, a jewel to prize, to adore and protect with pride. Only Jarryd could make Sri Lankans seem noble and wronged, a people gifted with a Paradise desired by all, besieged by invaders and savagely plundered. For Jarryd, Sri Lankans were ensnared and oppressed by the greed of others. He made even the local yobs seem like promising youths who needed only to be freed from the injustice of poverty and exploitation.

Everyone is pushed up against each other in the house that is Sri Lanka, their pride, arrogance, envy, hatred – and love – raging. People wanting peace, but fighting each other, people wanting to belong but also to rise up and be apart from all the others, each person secretly longing, reaching beyond their crowded house for something more, somewhere better. Perhaps there has always been a need for Sri Lankans to turn away from each other, to leap across seas to other lands and leave behind their close clinging house of fury and discontent.

Only Jarryd could make Padma feel pity for the lives of the villagers, and to forgive them their bitterness and poisoned tongues. Jarryd was her yoga teacher, but she had learned much more than yoga asanas from him, she had learned more from him than anyone.

“Are you still here?” Soma shouted. “If you don’t go now there’ll only be frozen fish left and I’m not cooking that muck. You can be the one to poison your guest!”

“I’m going, I’m going!”

She went around the house to the back of the garden. It was already too hot to be in the sun. Only the sea breeze and the shade of the trees made it bearable. How quickly the day moved forward after its cautious probing at dawn. Crows cawed. A woodpecker tapped high up in the jak tree. She unlocked the shed where she kept her new motor scooter, gleaming in the dark, glinting with possibility.

2

ROHAN STOOD AT his window watching Padma, out in the garden. She looked thoughtful and dreamy, her face tilted to the sun. She went inside a shed and came out wheeling a bright purple motor scooter, big and new and expensive-looking, gleaming obscenely in the sun. She threw her leg over the seat, climbing on with careful fluid grace, sitting bolt upright, strapping on a glittery lilac helmet. She was too much; everything about her was excessive. He had noticed her looking him over earlier, smirking; well, what did he care what she thought of him? The owner and manager – like hell she was! As she rode away, her skirt blew back, revealing a long brown leg, surprisingly muscled. He followed the delicate line of her thigh. There was something defiant and immodest about her. It was dangerous, if nothing else, to dress like that when riding a bike.

He felt himself watched. A stocky Tamil man was staring from the back of the house. The reluctant cook, Rohan presumed. The man looked furious, as if he had read Rohan’s thoughts, which of course he couldn’t have. In any case, Rohan had only been concerned about road safety. Rohan glared back and the man was the first to look away, going to an outdoor kitchen just behind the house. Soon there was a smell of a wood fire and blue-white curls of smoke wound out from the open brickwork walls.

Rohan left the bungalow and went over the garden. The dog lay slumbering on the porch of the main house, opening one eye as Rohan edged past.

“Good boy, Gustav,” Rohan said softly.

The dog thumped its tail and went back to sleep.

A young Western couple strolled past in the lane. He followed them. A breeze shook the coconut trees making them sway high above, branches whispering of long ago – of weekends at his grandmother’s coconut plantation, the adults gathered talking on the veranda and his cousins playing cricket on the lawn. He had wandered alone under the trees, safe in that world, no danger to look out for, only mad dogs and falling coconuts. The Western couple left the lane and entered a shack where a group of local men sat arguing at the bar. On the beach beyond the shack, other travellers lounged under palm-thatch umbrellas. Even from the lane he could smell their joints. There were more shacks, more bars along the beach, and on the land-side of the lane, after the villa, was an empty house, then another much larger house where five, maybe six, young local women were sitting outside, all piled onto a chair, their legs entwined. Their breasts were big and rounded, pressing out from thin strappy vests; buttocks curved in tight shorts. The women looked out at him. An arm rose up and waved.

“Hello! How are you? Are you coming to visit us?” they called. “Anè! Where are you going? Come back!” they shrieked as he kept walking.

The lane curved out of sight up ahead. It could have led to a dead end, or another strange house. He turned and went back the way he had come.

“Ah, here he comes! Why don’t you come and say hello! Ane! We’re missing you so much already!” the women shouted and burst into wild laughter.

Their jeers followed him. The men in the bars watched him go. He had been warned by his mother and aunts that villages along the coast contained just such places, but he hadn’t expected to see one so near to where he was staying. What a place to put a guest house! He paused before it now, innocently reposing in the sun, shielded by its bright jungle garden and high white wall with a burst of red hibiscus falling over it. He had first read of the guest house in a review he had found online: ‘elegant, simple, tasteful; a cut above the other guest houses along this unspoilt stretch’ a travel journalist had written. It was exactly what Rohan had been craving: somewhere unspoilt and simple, to rest and be alone, to let himself forget.

He headed up the lane, walking the way the taxi had come. The village houses here had rooms to rent, the houses painted in bright uneasy colours: rose-pink, canary-yellow, violet; an unnatural flat green – it was the Asia of his student travels in Goa, Nepal, Thailand – an Asia-without-comfort embraced then as a protest against the hotels with turbaned staff and infinity pools that one couldn’t afford and only went to in later years. He came to the top of the lane and a clearing with stalls and tuk-tuks gathered under the shade of a cyambala tree. Buses circled a bus stop. Nearby was a grimy café where a sweating man was making roti over a gas burner. Rohan walked around the clearing, inspecting the stalls. The stallholders reclined under their awnings, smoking, idly talking; a woman tugged a nit comb through a child’s matted hair. Rohan bought Jacob’s Cream Crackers, mangos, plantains, Bombay mix, beer and bottled water. Other vendors followed him around, offering him marijuana, magic mushrooms; lottery tickets, trips to turtle conservation beaches.

“You want a room? You want to stay in a nice guest house?” a group of excitable young men offered.

“No thanks.”

“Where are you staying?”

“The Villa Hibiscus.”

“Why stay there – it’s much too expensive! There are much better places.”

“Thanks. I’m fine.”

The men eyed him resentfully. He was glad to leave them behind and return to the lane. He looked past the coconut trees towards the beach. Such an incongruous mass, the sea, with its yearning rising green-blue swell and the deep-blue simmering stillness of horizon – a seemingly impossible whole, its line of division imperceptible. And above it all was the clear pale empty blue of sky – the blue of a shirt that his wife had bought him a long time ago, a shirt he didn’t wear anymore, needless to say. The air burned white, drained of all softness; the sun struck out from the sea. It hurt his eyes. He turned away.

There was a man outside the villa, peering over the wall into the garden. He spun round startled and fierce as Rohan approached the gate.

“I’m going in,” Rohan explained.

“You’re staying here?”

Gustav came down the path. As he came near he growled and started barking.

“Get lost you bloody dog!” the man snarled.

Gustav bared his teeth and hurled himself at the gate, barking wildly.

“Down boy!” Rohan shouted. “Jesus, what’s wrong with him?”

The man picked up a large jagged stone from the road.

“Don’t hurt him!” Rohan rushed forward, blocking the dog. “Gustav! It’s me. Remember me? Calm down, boy!”

“He’s just a little excitable, he won’t hurt you,” Rohan explained, but when he turned around, there was no one behind him.

Gustav strained to see into the lane with his paws on the gate, then he dropped down and wandered away. Rohan slowly entered the garden. The dog roamed idly under the trees. It barely looked up as he went up the path. The cook was on the porch of the main house, calling to the dog. It trotted up, wagging its tail. The cook frowned, looking over at the gate. There was no sign of Padma. The villa felt too quiet without her, abandoned-seeming. Had she gone to buy food for dinner? Had she met up with friends? He couldn’t imagine her friends. She had the careless disdainful confidence of the city girls who went to the fashionable schools and travelled abroad; it was hard to imagine her with villagers as friends.

But she was too unruly and uninhibited to be like the city girls who, for all their worldliness, were highly conventional and conservative – as he had discovered. Padma seemed foreign. She could have come from anywhere.

She had looked to have just run out of a shower when he’d arrived, which meant that she might live at the villa – but no young Sri Lankan woman from a well-to-do family would have been allowed to live alone at a guest house. The cook might have been a relative, but he seemed more like staff. There was something strange at the heart of the villa. He thought of the house down the lane and the hard, brazen laughter of the women. The sullying presence of that house reached into the silence of the villa. Rohan returned to his bungalow. He watched the cook come out of the back of the house and sit on the step and light the fattest joint Rohan had ever seen. The man looked up and scowled across at him. Rohan pulled the curtains closed. He paced about the room. There was nothing peaceful about this new freedom of his. He had strayed too far from the world he knew. A band of sunlight came through between the curtains and fell over the desk and across the floor. He turned on the fan and stood in its cool whorl. Despite everything he suspected, he felt soothed by the shelter of the villa. He chose a book from the pile he had brought and lay down on the bed, returning to a time when he had rested reading, after school. Like then, the fan whirled over him, its drone a rhythm of its own. He laid his face on the cool white cotton pillow smelling faintly of sandalwood, and let his eyes close. Once there would have been the cook scraping coconuts in the yard, the maid squatting at the outside tap washing cooking pots; his mother talking on the phone with her sisters, catching up on the day’s family news; and his father at the office, expected back later for lunch. Now there was only this room at the villa, and beyond it a world of aloneness and resentment, where people never wished you as well as you hoped. He dropped down through the silence, the stillness of the villa filling the room.

He slept longer than he had meant to. The sun had already set when he awoke. Someone had left him a bottle of iced water on the veranda, a packet of fried cashew nuts, and, more inexplicably, a hefty volume of all of Shakespeare’s plays. He drank the water and ate the nuts, watching the last streak of red in the sky fade to darkness. Dusk descended in one smoky unflinching sweep, the night filling the garden.

Inside, in the bungalow’s bathroom, in the buzzing brightness of a neon light, he shaved for the first time in days. He showered, feeling as if he had woken after a terrible illness. He dressed slowly, taking more care than he had in months, even for court appearances. Then he went over to the main house, going up onto the porch where two wooden armchairs posed, two sentry posts, on either side of the doorway. To one side was a low round table with a neat arrangement of everyday objects: ball-point pens, a pencil, a bottle of pills and a newspaper with its crossword half-done. He paused in the doorway with the veranda before him – a low-lit spacious room open onto the garden, wooden roof beams slanting down to white pillars on a parapet. Wicker lampshades cast a warm baskety glow over two round tables, while a third small semi-circular table was pushed up against the parapet where Padma was arranging cutlery around a plate that was round and white like the moon. She was wearing a lunghi with a long-sleeved blouse, clothes he thought of as belonging to a time long ago. Padma’s lunghi was printed with red and purple flowers and emerald green leaves, and was wrapped tight around her hips and falling long down to her feet, delicate in silver slippers. Her hair was pulled into a chignon, a red frangipani flower tucked into a fold. She moved a water glass, lighted an oil lamp and placed a fluted glass shade over the flame. There was something artful about her, about her slow smile as she surveyed the table, her face with its small nose and rounded cheeks, the soft curving line of lips and chin. Too much beauty could conceal too much, hiding all that was ugly and ruthlessly self-seeking beneath. Now he knew such things and he knew to be wary. He stepped into the room. She spun round with a gasp.

“What are you doing? Standing there like a burglar!” she exclaimed.

She looked terrified.

“You said dinner at seven.”

“Ah, yes of course!” She smiled.

“Are you alright? I didn’t mean to scare you.”

“You didn’t! Not at all!”

She looked him over as he went further into the room, then she giggled.

“What’s so funny?” he asked.

“You’ve shaved. You look nice.”

It would have been easy to let his defences be prised away, to feel flattered – that’s how it began. He said nothing.

“That’s your table,” she said, indicating the table she had laid. “You can work here anytime you want.”

“Work? Here?”

“So many great people have been inspired by the sea,” she said mysteriously and gazed up at him expectantly. Her lips were slightly parted and he saw the white gleam of her perfect teeth. He felt her presence; so near, he felt her inside his skin. He stepped back, pulling his chair out between them.

“Shall I bring you a beer?” she asked.

“Yes. Thank you.”

She went inside and he sat at the table with its lone plate and glass and fork and spoon, a solitary setting for a single man, for that was what he was now. Had he ever truly been anything else? The oil lamp’s flame fluttered inside its glass containment, futile against the darkness.

Padma returned with a bottle of Lion beer.

“Where’s everyone else?” he asked.

“Who?”

“The other guests?”

“There’s no other guest – just you and me and Soma.”

“But you said the place was fully-booked!”

“Others will come, don’t worry. There’s a couple due in a week, hopefully.”

“Hopefully?”

“Who knows with tourists? They see one thing on the news and cancel their holiday – it happens all the time around here. People that nervous should never leave home, that’s what I say. Don’t worry, Gerhardt will be here soon. You can chat with him.”

“Who’s Gerhardt?”

“Gerhardt Hundsler,” she said importantly.

“Who is he?”

“You haven’t heard of him?”

“Should I have?”

She looked astonished. “He’s a very famous architect – he’s designed many important buildings in Asia. He’s the owner here.”

“I thought you were?” he reminded her.

She didn’t flinch. “We both are. Gerhardt designed the villa and the garden a long time ago, but now it’s my guest house.”

“And he lives here?”

“No! He has his own house, in another village inland, it’s not far from here. He’s from Austria originally, but he’s lived in Sri Lanka for fourteen years – you can ask him all about it.”

Rohan hoped very much to avoid such a conversation. Long-term expats were the biggest bores of all, always wanting to tell you in excruciating detail about their discovery of the island you yourself had been born in, and thinking it was theirs to do what they liked with. He would have to be careful not to encourage the man, otherwise there would be no escaping him. And who knew what strange arrangement there was between him and Padma …

“Is this Gerhardt your employer?” Rohan asked.

“My employer?”

“Is he in charge?”

“Of me? Hah! That’s what he’d like to think!” She chuckled. “I’m the one in charge, actually. I don’t like working for other people. I have issues, you know, with authority.” She grinned infuriatingly.

A motorbike drove past, pausing by the gate, a man in a black helmet waited with the engine on. A woman approached, lit by the headlights, a thin angular body in a dark dress, a plastic lipstick-red belt pulled tight around her tiny waist. She lifted a thin doll-leg over the motorbike and sat behind the man, her hands resting on his waist as the motorbike turned in the lane.

“Interesting goings-on around here,” Rohan remarked.

Padma bit her lip.

“I came across a house earlier, further down the lane – there seemed to be a lot of people—”

“It’s a wedding. They’re having a wedding with lots of family staying.”

“Ah, that must be it.”

“I’ll go and see if your dinner’s ready,” she said and went inside.

The couple on the motorbike rode away for their encounter of the night, red lights fading behind them. Then all was darkness again.

Padma brought out the food: fried vegetable rice and fish curry – large fleshy chunks in a yellow gravy of coconut milk.

“What’s this?” Rohan poked at the fish. “I wanted steamed fish, not curry.”

He tasted a spoonful. It was nothing like the crude overdone fare of village restaurants. It was cleverly spiced, rich and subtle, made with care like the curries he had grown up with. But he refused to be seduced; the cook had ignored him on purpose. Rohan had had enough of people not listening to what he said.

“I said no chilli,” he protested. “And this is fried rice.”

“The cook must have made a mistake. He must have made his usual things. He – er – doesn’t like people to change the menu.”

“Menu? Some menu!”

“But tomorrow he’ll get it right. Don’t worry. I’ll make sure of it.”

“I saw him watching me earlier – what’s the matter with him?”

“He can be a bit funny.” Padma laughed nervously. “He’s very suspicious of new people.”

“What’s he think I’m going to do?”

“It can be a little strange around here sometimes.”

“I noticed.”

The dog ran out of the house barking. It raced into the garden. Padma darted to the parapet and stood looking out.

“It’s Gerhardt,” she said with relief.

The barking stopped and some moments later, a tall tanned old Western man came in.

“Hello, there!” He smiled at Padma, then at Rohan.

Gerhardt had blue eyes, very bright and pale against his tan, and white hair parted in the middle. He was dressed in cotton chinos and a pale cotton shirt, elegant and relaxed looking.

“So how’s everything? You’ve settled in okay?” he asked Rohan.

Despite the man’s friendliness, Rohan felt himself carefully checked. Gerhardt, he noted, spoke with the same Germanic accent as Padma; a resemblance that persisted in being unsettling.

“I hope the food’s alright for you?” Gerhardt said.

“Yes, yes, he loves it!” Padma pushed Gerhardt out to the porch. “You sit down and relax, Gerhardt, I’ll bring you a nice cold beer.”

Rohan saw him settle in the armchair by the table with the newspapers and pills as Padma returned. Gerhardt sat thoughtful and rested, gazing at the garden. His garden. His house. He seemed very friendly with Padma, and didn’t seem to mind showing it. He didn’t seem embarrassed, or afraid of being found out. And she wasn’t frightened of him, but then who knew what went on behind closed doors? Irregular goings-on among expats and villagers had been going on for decades in Sri Lanka.

“So many foreigners have invaded our villages and are corrupting the poor,” his mother and his aunts would often lament.

With their social club, they ran fundraising events to help children rescued from such dangerous influences, housing and educating them in orphanages. Rohan had been made by his mother to donate to many such institutions, and he had seen for himself the solemn scrubbed rows of children watched over by strict unloving staff, protecting them from Western predators. There were many unwholesome households hidden away in remote coastal areas, the natural beauty of the place a mere backdrop for the ugliness going on. The certainty grew in Rohan that he had stumbled upon just such an arrangement.

He watched Padma take out a large tray to the porch with a bottle of beer, a can of Coke, two glasses, two plates of rice and fish curry. She sat eating with the man, the two talking in low voices. To Rohan, straining to hear, their talk sounded like genuine guest-house business. He thought he heard the rat in his bungalow mentioned and Padma suggesting that they cut down a tree, Gerhardt protesting. It was exactly what a manager might talk about with the owner of a guest house, but there was more in their seeming friendliness, a different kind of closeness. Rohan went nearer to hear better, standing at the dresser pretending to read a book.

“That’s a fabulous guidebook,” Padma said behind him.

He turned and she was there holding the tray with the empty bottles and used dishes.

“You should buy it. Our friend wrote it,” she said.

He glanced at the book in his hand: Reflections on A Teardrop by Jarryd Gunnerson’.

“It’s really good. I’m not just saying it because he’s our friend – it’s really amazing—”

“Yeah, maybe.” He slipped the book back onto the pile.

“No, no – buy it now! You’ll love it, trust me.”

He searched in his pocket for the money and found some. She took it triumphantly and went off with the tray. He sat down at his table and studied his new purchase, a slim volume, like a book of poetry; it looked slight and home-made. He set it aside. Padma returned and took his plate. She didn’t say anything about his having eaten all the fish and rice – it hadn’t occurred to her to triumph over him, he realised. She merely looked pleased that he had enjoyed his meal. A knot loosened in him, a sudden easing, a feeling of contentment and safety spreading through him, despite everything. Then Gerhardt came in, asking about the state of the roads on his journey that morning. Rohan told him, alert all the while for sly questions and offers of dubious services.

“How about some fresh coffee?” Gerhardt asked. “We can do real coffee?”

“Okay. Thanks.”

Rohan had meant to refuse and get away, but he was suddenly unwilling to leave the gentle glowing veranda with the darkness of the garden and the lonely roar of the sea pushed away, the old man bringing over a chair to Rohan’s table.

“Padma – tell Soma to put some coffee on,” Gerhardt called into the house.

Gerhardt sat back in his chair, his eyes searched the garden. He seemed to have forgotten that Rohan was there. A scooter sputtered past the gate. Silent shadowy figures passed in the lane; the old man’s gaze followed them.

“Have you owned this place long?” Rohan asked.

The pale bright gaze turned back to him.

“Fourteen years. We’ve only just recently made it into a guest house. We had a good review in the International Guardian Online, did you see it?”

“Yes – a very good review—” Rohan tried not to sound accusing.

Gerhardt smiled. “Possibly a little bit over-enthusiastic. What can you do, the fellow came to visit and loved the place!”

“You said ‘we’ – does Padma also own this guest house?” Rohan watched Gerhardt.

“It’s all her business. I have my own architects’ practice. I live in the next village now. It’s been a year of changes – it still feels strange not living here.”

“This was your home?”

“And Padma’s.”

“She lived here with you?”

“Right from the start! The building work wasn’t even finished when she arrived.”

“She must have been very young.”

“Nine years old, she was. Nine and a half.”

Gerhardt didn’t look ashamed. There was no hint of remorse or regret at what he had done.

“Oddly enough, this place still feels like home,” Gerhardt reflected. “I always believed that work would root me, but it is children who define one’s world. Home is a construct based entirely on people, wouldn’t you say?”

“Home is where I keep my things.”

Gerhardt laughed. “You’re still young. Maybe one day you will understand. It’s terrifying when a child leaves; you see all too clearly that Time is irreversible. I had a taste of it when Padma went to live in Colombo – it felt so different here. That’s when I bought the new house and started working on it. I was going to keep this place for weekends, but she’s come back, would you believe!”

The old man had a hold over Padma. Somehow he had made her return after an attempt at escape. Offering her a business to run would have done it. Maybe he gave her money as well. Possibly he paid her family.

“The villagers do anything for money these days,” his aunts used to say. “The poor are so easily corrupted.”

Padma had been a child when she came – what chance would she have had against a rich controlling foreigner? His control was all she had known. No doubt her family had handed her over for the usual laughable gain – a television or a stereo or money for drink and drugs, perhaps. No wonder the seedy dregs of the West trekked gleefully over to Sri Lanka where ordinary money could be turned into great wads of cash and buy them anything that their poisoned hearts desired.

“Now she has her own income,” Gerhardt explained. “She is totally independent. That’s the best way.”

A guilty conscience if ever there were one. No doubt Gerhardt thought himself superior to all the other dirty old men by being so generous afterwards. Rohan longed to tell him exactly what he thought of people like him, but there was no knowing whom this Gerhardt might know. He could easily turn out to be well connected and dangerous. One had to look out for oneself in Sri Lanka these days; no one cared about the truth or justice; no one listened except to save themselves. Rohan had to stay out of Padma’s troubles, he had only just escaped his own.

“I’m going to bed.” He pushed back his chair from the table. He couldn’t stay near the disgusting old man a moment longer.

“But what about your coffee?”

Rohan faked a yawn that halfway through became real.

“Are you still tired from your journey?” Gerhardt looked genuinely concerned. “Was the traffic very bad?”

“Yes, very bad.”

“Oh dear. Never mind, we can have coffee another time, you go and get some sleep.”

The face that looked up at him seemed full of kindness.

‘He’s good, I’ll give him that,’ Rohan thought glumly as he left.

He walked slowly through the garden, resisting returning to the bungalow faded into shadow at the end of the lawn. At the side of the main house, a window glowed pink through curtains drawn against the night, a secret other life going on inside, private and closed to him. He went to his room, to the bed with its nets billowing with the fan, to lie rootless and empty inside its cool cocoon that felt of nothingness, not even the past.

3

GERHARDT TOOK THE long route to the villa for breakfast, leaving his village and walking down to the sea road and onto the beach – a pale gold smoothness early in the morning. The sea was gentle, just woken, resting across the horizon. The day had opened and a new world was before him; each day a different view, a new configuration of sky and sea and beach achieving its own perfection. An incredible feat, to be so effortlessly, ceaselessly renewed, and so completely, but this was the magic of Asia, this power to regenerate with a new and greater vigour each day. It kept one forever in the first thrill of one’s excitement. Mornings in Asia offered such absolution; anything seemed possible in that glorious light, the sun a welcome caressing warmth in the quiet loveliness of the day. It was easy to bask in that hopefulness, in the delusion of endless possibility, even if it only lasted for those first early hours.

But that morning he was uneasy, for he had been thinking about Sunny; Sunny who was really Sugathapala, the most devious, grasping individual one could ever meet. Gerhardt had been expecting Sunny ever since Padma’s return to the villa several months earlier, because Sunny’s many spies and underlings would have told him she was back – but he hadn’t shown up once. And now with Padma starting her own business, it was completely unlike the scoundrel not to turn up to pry and attempt to take something away. Gerhardt reached Nilwatte Beach and walked towards the lane, leaving the sea behind. Stamping his feet on the tarmac to shake off sand, he crossed over to the villa. Gustav ran down to him and he walked with the dog at his side up to the house. Gustav would let them know if Sunny came, the dog somehow knew to resent Sunny’s presence. Gerhardt used to sometimes encounter Sunny in the town in the old days, and whenever he’d had Gustav with him, the dog had turned savage. At least with Gustav around, Sunny could never come too close to the house.

Soma brought coffee and toast out to the porch. Gerhardt sat eating and going over his work for the day: two client meetings at his office, back at his house; a site visit and a second viewing of a cottage he hoped to buy and renovate for a holiday rental business of his own. Building the bungalows for Padma’s guesthouse had been the inspiration. The young so effortlessly renewed one’s enthusiasm. He always had new ideas when Padma was around. What a joy to have her back again. Ruth, his oldest and dearest friend in Colombo, had wanted Padma to travel the world. Even as a young woman, Ruth had believed that a true self was only to be found in foreign lands – but one’s true self could be found wherever one felt inspired. Padma had always loved the villa and this was why she had needed to return. Ruth too, in the end had returned from her travels to her homeland. People thought he had followed her to Sri Lanka – possibly he had, but the island had called to him. All of his work, in one way or another, had been fuelled by this single decision to go where he felt called, the island’s splendour had inspired him from the start, with its majestic ancient heritage and wild natural abundance. He always returned in his designs to the modesty and elegance of its old buildings. It was hard to imagine what he would have built if he had stayed away. Padma was finally back where she belonged. She had never loved anywhere else as much, so why send her away? The villa was her home, it was a world he had made to hold her safe and Sunny couldn’t change that. Gerhardt wasn’t afraid of Sunny; Sunny could always be paid to go away.

“Good morning!” Padma came out of the house eating cereal.

She bent and kissed him on the cheek.

“What’s the matter?” she asked at once.

Like a psychic, she was, so perceptive. And bright as a button; she always had been.

“I’m just enjoying the morning,” he said.

“Have you seen that crazy Rohan, yet?”

“No. And by the way, that’s not a very nice way to talk about your guests.”

“He’s strange, don’t you think? Why do you suppose he ran off before coffee last night? What a weirdo!” She gazed at the small bungalow.

There was something different about her that morning – so impatient and dishevelled and bright-eyed.

“Soma had a bad feeling about him, right from the start,” she mused.

“Soma has bad feelings about everyone.”

“Yes, but this time I also have a bad feeling.”

“Good God, not both of you.”

“I’m telling you, there’s something really strange about that new guest. He’s hiding something.”

“Like what?”

“I’m not sure. He’s up to something though, and it’s definitely not a screenplay. He’s running away …”

“It’s only his first morning, give him a chance! And by the way, shouldn’t you go and get dressed properly?”

She had changed from her nightclothes into her clothes from the day before, unusually for her she was unwashed and crumpled.

“In a minute, I’ve got something to do first.” She crunched on her cornflakes, her eyes still fixed on the small bungalow. “You know, Soma thinks he might have killed someone.”

“My goodness!”

“He’s got the heaviest suitcase.”

“It’s called luggage. Guests have it sometimes.”

She giggled. “You didn’t try carrying it – it was so heavy, not like usual luggage; a dead weight. He could easily have had a body inside.”

“He’s a bit stressed, that’s all.” Gerhardt drank down the last of his coffee. “The best thing we can do is leave the poor fellow alone, let him have a good rest.”

“Maybe.”

Gerhardt thrilled to see her returned to herself, once more full of warmth and laughter. Her years at the University in Colombo had dulled her; each time she returned she had seemed more lost, more lacking in purpose. The university had failed to inspire her, yet the failure had been deemed hers – and it was he who had urged her to go there, to try and try again to succeed where she could not thrive, for he had feared that a lack of a degree might burden her – yet here she was, unshackled from that fruitless pursuit, shining and new again. Ruth had worried that Padma would never meet suitable men away from Colombo, but love could wait. It was work, not love, and certainly not marriage, that gave purpose to life.

“Ah – ha! Speak of the devil,” Padma murmured.

Rohan had come out onto his veranda, a tall solemn figure looking out at the day.

“Whatever you do, don’t upset your guest, okay? He seems a little fragile,” Gerhardt advised.

“Me? Upset Mr Rohan? Look – he’s settling down; aha! So he’s planning to keep guard.”

“He’s reading.”

“He’s got something in that suitcase he doesn’t want anyone to see.”

“Maybe he just wants to relax.”

“Don’t worry, I have a plan.” Padma darted inside.

Gerhardt watched a fat mynah bird on the mango tree. Two parrots on the top branch calmly surveyed the devastation that their chattering tribe had wrought on the ripe fruit. It was possible that Sunny had lost interest in Padma. No one seemed to know what Sunny was doing these days, but there was talk of him working for someone rich and powerful – possibly one of the many Russian mafia mobsters based on the coast, trading in arms and drugs and women – that would keep Sunny busy. Good riddance to the scoundrel. Even if he did ever come by the villa, Gerhardt had plenty of money set aside, ready to pay him to go away. One thing he knew was how to handle Sunny – he’d had plenty of practice in the past twelve years.