Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The Lilliput Press

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

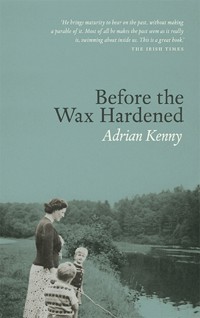

Originally published in 1992, this childhood memoir, revised and augmented, now has the status of a modern Irish classic. On his first trip abroad, Adrian Kenny observes that the signs are in one language only. There is no need for translation: there is nothing behind. Not so in his suburban childhood and adolescence, where Mayo is behind Dublin, poor fields behind the bourgeois drawing rooms of Rathmines, wildness behind authority. Attached to both, his attempts to reconcile them take him from close certainty to total collapse in the year of change – America, 1968. 'What was it all for?' his father asks. 'It's like the end of the Aeneid,' whispers his friend. 'You came at the end of that world,' Father Wilmot says. The end of Latin Mass, maids, floggings and charcoal suits. The author's keen eye and clear style lends this portrayal of an individual and a generation the truth and elegance of an enduring work of art.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 365

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2017

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

THE LILLIPUT PRESS

DUBLIN

Dedication

To Mary and Eva

Contents

Epigraph

I. JOHN EDWARD

— 1 —

— 2 —

— 3 —

— 4 —

— 5 —

— 6 —

II. UNCLE PAUL

— 7 —

— 8 —

— 9 —

— 10 —

— 11 —

— 12 —

III. MARY COLE

— 13 —

— 14 —

— 15 —

— 16 —

— 17 —

— 18 —

IV. FATHER MACNAMARA

— 19 —

— 20 —

— 21 —

— 22 —

— 23 —

— 24 —

Epigraph

‘… Remember the time

Before the wax hardened

When each of us was like a seal.

Each of us carries the imprint

Of the friend met along the way;

In each the trace of each.

For good or evil,

In wisdom or in folly

Each stamped by each …’

From The Mirror Maker

by Primo Levi.

I. JOHN EDWARD

Going somewhere, driving from an unfamiliar direction, preoccupied too, it was some time before I realized I was in familiar country. Purple clematis on a white-washed farmhouse … the sudden dark of a high-hedged road: I had my bearings when I came out onto the motorway. There was the pub, with teak-windows now, on a raised beach of loose chippings. On the other side – the signpost pointing to the squat steep hill. Joining the traffic, accelerating again, I glanced in the rear-view mirror and saw myself walk up it twenty years before.

*

The headmaster led the way down a wide, high-windowed corridor – ‘I’ve always found the better a fellow has been brought up, the less fuss he makes about his quarters.’

I smiled back and he opened a door into some narrower, darker passage. He stumbled against a fire extinguisher, then opened another door and stood politely aside. An iron school bed, a plywood chair and wardrobe and a mat of jackdaws’ twigs on the hearth.

‘Really … these girls.’ He gathered up the twigs and set them in the grate, spanked pink hands off one another. ‘No fires, if it’s all the same to you.’ He patted the radiator, then fiddled with the stopcock.

When I had unpacked, I went for a walk down the avenue, and down the road. A line of cars was coming up, bringing the boys back to school. Registration numbers from all over Ireland. Tow-bars. My stomach seized up with misery.

At the bottom of the hill was the main road, being widened into a motorway. Dublin 60 – the signpost was lying against a broken ditch. A break in the eastward traffic and I was on the cats eyes. A break in the westward line and I was across the road and into a pub I had often noticed when I was one of those travellers.

‘And now the Mullingar millionaire, Joe Dolan! “Make Me an Island, I’m Yours”. Take it away, Joe!’

A man behind the counter turned down the radio, looked up from a newspaper and read me slowly from head to shoes. ‘Not a bad old day.’

‘Nice old pub.’

‘Old is right.’ He watched me try a solitary game of darts between sips of beer. ‘On the holidays?’

‘Not exactly.’ I threw a few more darts before I owned up. I was going to teach junior English, French, Latin and Nature Study in the boarding school.

He took my glass and topped it up foaming. I said ‘Whoah’ and in a minute we were into the GAA, horses, Northern Ireland and the latest Cortina. I felt my armpits slobber with perspiration as I mistook Gowran Park for a football team. I tried to save face, taking a quarter pint in one gulp, but he had returned to his newspaper as I looked back from the door.

It had all taken about five minutes. Joe Dolan was singing the same song. I sang it to myself as I walked back up the hill. Lying in my iron bed that night, I heard it on the transistor my father had given me. It was in the air all that autumn of 1968. Down in the rushy rugby field the boys sang it in the scrum and on the long Sunday afternoon crocodile walks too, until I knew it by heart. I used to hum it to myself as I wondered how I had ended up here: my first pause for thought; a small crossroads like the one at the bottom of the hill. Even in Prep, as they called evening study, I hummed it, leaning against the rail before the glowing Romesse stove, looking at the rows of bent heads, going over the past in my own head. Do we weave an image of the past deliberately as a magpie roofs its nest? Or spend our life pulling away at the impenetrable first roof?

— 1 —

Spring. Morning. 1955. Indelible details.

Around the breakfast table: father, mother and growing children – my family, clear as the vista of hills from the Rathmines Road that vanishes below blue rooftops as you approach.

74 … 76 … The same postman had served the house for years and still no one knew even his Christian name … 78.

‘Post!’

‘Ssh!’

‘After the time signal –’

‘Ssh! Ssh!’

‘It’s only the Tribune –’

‘Oh, my God!’ My father got to his feet and stood under the wireless. Silence! for the voice from that high shelf which on other mornings announced the climbing of Everest, the death of Stalin … all those items we heard out patiently before –

‘And the weather …’

The announcer drew breath and my mother said as one quick quiet word ‘Maybe in God it’d rain and you’d sell some wellingtons.’

‘… Rain spreading from the West.’

She breathed out a silent aspiration and cut open the twine of the parcelled up Connaught Tribune and out fell –

‘A letter!’

She glanced at us, then around at the open kitchen door, miming a Ssh! of her own.

‘Will ye have more tea?’ Sure enough, in stepped Delia, eyes country-quick as Mama’s, hoovering up newspaper, envelope and letter.

‘… and a request now for the O’Reilly family in Edenderry. That’s Josie, Ron, Brid-Nuala, Angela …’

‘Are you right?’ My father emptied his cup and stood up.

In ten minutes the house was empty except for my mother and Delia, and the letter. I pictured it glowing pink behind the Sacred Heart lamp – our letter holder; scalding Delia with curiosity, as they went about the washing, bed-making and cooking, always together; my mother giving out carefully selected morsels.

‘Delia you didn’t know any Rodgers in Spaddagh?’

‘Sure I know Spaddagh well. Don’t you know –’

‘They say he killed himself.’

‘What are you saying, Mrs Kenny?’

‘They got the gun beside him on the table and a string on the trigger tied to the door. They say he must have called the dog.’

‘Oh my God, Mrs Kenny!’

‘And did you know him?’

‘Didn’t I know him well! Don’t you know –’

‘They shot the dog.’ Mama let the talk fall back to the subject. All day long backing and advancing, never quite meeting, went their conversation. Mama wore an apron like Delia’s and was sometimes mistaken for the ‘maid’, a word I used once in their company. They had been sitting together at the fire, darning socks, and had both lowered their heads in embarrassed silence.

Down the mid-morning empty road came the cavalcade of carts and vans: milk man, bread man, waste man, egg man … and then the messenger boys. Together my mother and Delia dealt with them, together again they darned and answered the door to the mid-afternoon procession of beggars, tinkers and charity collectors who had discovered this house. Together with the family after tea, Delia would join in the Rosary below the Sacred Heart lamp, where the letter still glowed.

But no rain. Out came a hot April sun instead. My father seemed in no hurry this morning and as we drove to school, he went by a new, longer way, turning down a wide road with chestnut trees on either side. A maid in uniform letting up a blind looked out as we stopped. The V8 engine began its hysterical turning-over. My father rolled down his window and pointed to a For Sale sign, with Sold nailed over, standing in a garden. The roof and bay windows seemed huge.

‘That’s your new house, boys.’ He gave the engine a rev. ‘Didn’t you know that boy Murphy in school?’

‘He’s gone to Canada.’

‘That’s the one. That’s where he used to live.’ Rolling up the window again and answering our questions, he drove on to school.

I had sat beside William in class: a big quiet boy with orange hair and wide ears. He had not come back after the Christmas holidays and, when his desk was taken away, we were told he had gone to Canada. We were not told why, but ‘To have his ears cut off’ appeared from nowhere, as mysterious and convincing as a catechism answer.

Up the avenue went the line of cars: Rovers, Humbers, some shining black ones with C.D. on the back – which I thought stood for Canada – and a few small ones. The big ones, driven by men, dropped off boys in maroon blazers on the gravel island and turned and drove away again. The small ones, from each rolled-down window a woman’s head jutted out, stayed behind making a corral around the rector.

‘Great Scott!’ He laughed, lifted his biretta, scratched his head and replacing the biretta, strolled to the next window.

‘Father O’Conor is a gentleman,’ my mother said. The very way he walked up the big steps of the schoolhouse made it seem as small as our own. He stood under the fanlight looking at his pocket watch and from the other house the priests appeared one by one, chatting under a matching peacock tail of glass for a moment, then coming down the steps, each carrying a little pyramid of exercise books, books, chalk box and duster. Father O’Conor’s own house in the west of Ireland was as big as both these houses put together, my father said. He leaned out of the window to tighten my tie, spannering up the knot with a finger and thumb until it was as hard as a nut, and then following the procession down the avenue.

The first time I had come here I thought we had taken a short cut into the country. Turning off the busy main road through a gap between houses, we went up an avenue between bushy back garden walls, past a gate lodge and then between a field of snoring cattle and another where a man in a white polo neck was mowing with a scythe. Now the same man, in a black gown and with a roman collar as high as a polo neck, was blowing a whistle. We all formed up in lines.

‘In the name –’

Pause, as a desk seat rattled. Silence.

‘– of the Father and the Son and of the Holy Ghost. Amen. Hail Mary full of grace the Lord …’

Pause, and our lazy voice was shown up. Father O’Conor’s eyes ran over us from mouth to mouth, his own moving again as our voice rose. Pause again as we rose too loud, moving with us again. ‘Now and at the hour of our death. Amen.’

‘Father, may I leave the room?’

‘Quickly.’ Father O’Conor thought of something. ‘And, Owen –’

‘Yes, Father?’

‘Turn on the taps a moment, please.’

Lucky Owen. We listened to the water run while Father O’Conor stood in a corner and leaned an ear to a pipe going up the wall. Everything in the room was new except his gown. He took a bit of bright brass pipe screw from his pocket and looked through it at the light, then left it on the table beside his breviary and Latin for Today.

‘Will I tell him, Father?’

‘Father, look what someone did to the floor.’

Someone pointed to a scrape on the new tiles right beside my desk.

‘Adrian?’

‘It was William, Father.’

‘Is it true, Father, about William?’

‘Yes, they’ve gone to Canada.’

‘To have his ears cut off?’

‘By Jove!’ Father O’Conor laughed, his eyes running across the rest of the floor and along the new painted walls and the rows of yellow-varnished desks.

‘We’ve bought his house, Father.’

‘Father, how old is this house?’

Father O’Conor took up his grammar, but slowly. ‘I should think about a hundred and twenty years.’

‘And how old are you, Father?’

‘Father, couldn’t you be King of Ireland, if you wanted to? That’s what my father said –’

But Father O’Conor had stopped smiling and, as if a skin had been peeled from his face, he wore now a chilling expression. ‘Good grief. ’

A mouse!

It ran across the bright floor and into the library, a cupboard in the wall. We got up to watch Father O’Conor go down on one knee and open the door. His hand, drawing from under a frayed black sleeve a frayed white cuff held by pale gold oval links, reached to part the rows of books: The House at Pooh Corner, The Bog of Stars, The Children of the New Forest …

‘Father!’

In fright the mouse jumped down onto the floor, down the avenue of shining shoes, skating like a dodgem car by the skirting board, all the way around and back into the library again. Father O’ Conor shut the door. The cold look left his face, but no one spoke.

‘Now. Open your books, please. Without bending them back. Now …’ He put a hand in his pocket – another clink of metal – and took out a crumb of chalk. ‘Now. What did I do just then, when I opened the door? I went down on one knee … I …?’

‘Knelt, Father?’

‘When we go into chapel first we –?’

‘Genuflect!’

‘We genuflect. We “flect” the “genu.” Now …’ He caught the crumb in his nails and wrote the two words on the blackboard. ‘Now. What do we do when we genuflect?’

‘We flect the genu, Father.’

‘In English, we –?’

‘Genuflect.’

‘But how do we genuflect? We bend our –?’

‘Leg, Father.’

‘No.’

‘Foot.’

‘No.’

‘Knee.’

‘Thank you, Adrian. We bend our knee. We flect our …?’

‘Genu.’

‘Good. So genu means –?’

‘Knee.’

‘And flect means –?’

‘Bend.’

‘Flect means bend. Now …’ Father O’Conor looked out of the window. ‘Now. Can anyone tell me another word we get from flect? Flect-flex-flexi …’

Two dozen pairs of eyes followed the long white hand opening and closing in the air.

‘Flexible.’ Again Father O’Conor took up Latin for Today, put it down again. ‘Now –’

There was a knock at the door and we all stood up. We all sat down again. Father Williams flicked his pencil down the roll-book, as easily as he swung the scythe.

‘Peter, Father.’

‘Mmm …’ He shut the roll-book, opened another. ‘Milk?’ He counted hands with the pencil point. ‘Two bottles?’ He counted again. ‘Gentlemen.’

We stood up and sat down again.

‘Flexible …’ Father O’Conor looked out of the window again and then, as briskly as Father Williams, he suddenly dusted the chair with a wing of his gown and sat down, his book held up straight before him.

‘“Vasto” – and the stress is on the first syllable. “Vas-to. Vas –”?’

‘– To’

‘We’ll begin.’

But by my Hopalong Cassidy watch, class was over.

The next class was different. Father Wilmot came in and said the Hail Mary and the right hand that gestured Amen to his breast continued smoothly to the table for his books. He never sat at the rostrum but came down into the class, sitting on one of our desks and moving the owner to sit in with another boy. He gestured to a window and a boy shut it a little. Already Father O’Conor was outside, steadying his biretta with one hand as he made his way across the fields. Another gesture, lordly as Father O’Conor’s – yet different somehow, and another boy wiped the board clean of ‘flect’ and ‘genu’. Silence then for a whole minute while he polished his glasses with a snow-white handkerchief.

Then –

‘Well, who was listening to the “The Foley Family” last night?’

Someone put his hand up and snapped fingers. Father Wilmot looked politely past him as if he had farted.

‘We don’t listen to Radio Eireann …’ Rory sounded sure of the right answer, but he too went red as Father Wilmot glanced past him.

‘Jim?’

‘Yes, Father?’

‘Wasn’t it very good? “Sufferin’ duck –”’ Father Wilmot said with a Dublin accent. I was ready to supply more, but Father Wilmot had moved on and was telling us now about a meeting he had been to the previous night where an – he paused and nodded slowly – ordinary working man had stood up from the audience and made his point with – he nodded slowly again – absolute clarity. Somehow this reminded him of something else. Now he was telling us about a place called Emo, his noviciate, and about a boy who had worked in the kitchen there who, when he had blacked and polished the range, would say – Father Wilmot imitated a country accent, though not so well as a Dublin one – ‘There’s style in that.’

In his own voice he said ‘What’s style?’

‘Father.’

‘Jim?’

‘Jack Kyle has style.’

‘Good. And Anthony?’

A few minutes of this and then, smoothly as if we had reached the end of a page, Father Wilmot turned to the book open on his knees, stroking it flat with the backs of his fingers. He gave a small yawn and said ‘Tell me, did I give you memory work?’

While someone recited, he took off his wristwatch and left it on the desk beside him. Later in the class he might take off his glasses and leave them on another desk. Our exercise books were gathered on a third, and so on until he occupied the whole front of the class. He spoke so low that the boys at the back had to lean forward to hear. When the bell rang, he paused irritably as if an aeroplane was flying over and then continued, often for five minutes beyond the time.

This must have annoyed Father Rowan, for the first part of our break was taken up by his Rosary. As we ran outside, Father Williams called ‘Walk, gentlemen!’ As we walked we saw Father Rowan standing in the courtyard and we rang again.

Father Rowan’s shoes were patched and, when he flected his genu, we saw that his socks were lumpy with darns, but he too had a manner as commanding as Father O’Conor’s or Father Wilmot’s. There was something thrilling about the way, the morning he saw a boy talking during prayers, his face hardened red like a woman’s and he walked up to the boy and slapped him across the cheek.

There as we prayed was Father O’Conor outside again, discussing something with the gardener’s wife, who stood in her cottage door with a dripping mop in one hand and a red-haired baby in the other. In his hand, Father O’Conor had a broken budding branch and as we ran outside into the yard he stopped suspects, gently putting out his hand and then firmly clutching them by the elbow and showing them the branch.

‘Do you know anything about this?’

‘What’s that, Father?’

‘This is lilac!’ His voice grew angrier each time he said it. From someone he must have an explanation. By the end of the break there was a note on the board in his thick-nibbed black writing: Boys must not play with their balls on the avenue. Chas. O’Conor S.J.

Ten minutes break and a three-acre field before us.

‘Chariots!’

Big boys paired off and bound together and a small boy climbed on their shoulders and was carried full speed down the field, knocking off other charioteers as he went.

‘Yip yip alloi! Ben Hur!’

My horses were brothers, Joss and Art, galloping as one and, as the whistle blew, cantering off the end of the field and out of sight down the back avenue. We rounded a bend, passed two senior horses on their hind legs smoking a cigarette, trotted down a path walled by shrubbery and topped with the boles of beech trees. High up were the scars of copperplate initials – A.B. 1891 – which, I thought, must once have been as low down as the furtive new ones – A.K. 1954 – still a terrible yellow in spite of all the clay I had rubbed in.

‘Did you really buy Murphy’s house?’

‘Yep.’

‘Then you’ll be right beside us.’

Through a flash of bluebells, past a summer house, along an ivied wall, pulling up at the only break in the boundary – a narrow gate set in a fence of high green galvanize whose top was cut into jagged spikes. Outside, the world was going on as usual. A motor car, a guard on his bike, a girl passed by. A bread van halted and the horse put his head into a bag of oats. Joss and Art stepped a foot outside and pawed the pavement with their heels.

‘You’re meant to be gentlemen in there!’ The bread man jumped to catch the bridle as the horse reared and scattered oats high in the air. We wheeled back and galloped the rest of the boundary, whinnying behind the last tree, where I dismounted.

When we were inside Father O’Conor was out. Now our class was outside he was in, standing at one of the big front windows looking out over the cricket field. Signor Agnelli felt the gaze bore into his back as he drilled us. He wheeled the column so he was facing the windows. We were behaving well. Two dozen pairs of white canvas shoes marking time in the grass, under each arm a short wooden baton exactly horizontal. Still marking time, Signor Agnelli came down the line calling instructions through the whistle in his mouth; quick-stepped backwards to the head again.

‘Attention!’

‘Every second boy –’ He waved his rhino skin wand and the line became two lines.

‘Close up!’

‘Quick march!’

‘Sapristi!’ He came alongside blowing his whistle. ‘Halt!’

We began again and this time both lines were parallel. Straight down the field – a hundred yards, two hundred … Whistle! And the lines peeled apart, marching like duellists in opposite directions. Another shrill and we turned back, marching parallel again, past Father O’Conor’s gaze, back to where Signor Agnelli stood, hands on hips, smiling.

‘Every week. You mus’ be absolutely perr-fect!’

‘Signor, why?’

‘Father O’Conor – he knows.’ He glided down on one knee, as he had the day the bishop called, and tied his natty shoe’s lace, glancing back at the big window.

We had him again for drawing, the last class of the day. The sun had gone around and left our basement room behind, but Signor Agnelli was making another on the blackboard. With a wooden compass he made a circle three feet high and then on a shorter compass he filled it in with petal shapes, as symmetrical as his army drill figures, which he talked about as he worked in the coloured chalks with the heel of his small olive hand. Yellow … yellow and blue … green … green and blue … Yellow.

‘… And the sergeant, when he got those boys with the white hands, by jeengo! Did he give them work. Kitchens … latrines … everything! ’ Now he was telling us about his days in Mussolini’s army.

Up on tip-toe, finger-tipping in white on yellow, he was reminded of an old Roman academy painter whose studio he used to visit.

‘… And when he took the leetle brush and touch the face, the face of the infant Jesus … Such ex-pression. My God! In-credible!’

Down on one knee again, smudging blue on red, and now he was talking about a woman he knew, an opera singer. She had once used a dressing-room that had been used the night before by Paul Robeson.

‘… And the smell. The smell. In-de-scribable.’

He cleaned his brilliant hands on his M.A. sleeves and walked to the back of the class to look at the figure. It was like a burning wheel. We were even quieter than we were in Father Wilmot’s class. I loved this last class of the day in the way I loved, after my bath on Saturday night, sitting in front of our kitchen fire. When we did get up, we stood around Signor while he nicked out mistakes with a corner of his duster. He skipped into the air and left the duster out of reach on top of the board. But next morning Father Hillery, though an inch shorter, had got it and wiped everything away with a cute grin.

‘How are you getting home?’

‘Walking.’

‘We’ll be with you,’ Art said. His brother said, ‘Is Mummy not calling?’

We went out the back gate but the road was empty, except for the sparrows still hopping about the horse’s spilt oats. Joss and Art never seemed to know if they were being called for or not. My brother and I often passed their mother, sitting in her small car dressed in clothes as bright as Signor Agnelli’s drawings. One day she had a high hat like a witch’s, but with green veils falling from the crown. Another day she gave us a lift and I noticed she had bandages on her wrists. When I asked her why, she said nothing. Not a rude silence, just the way when one day we gave Joss and Art a lift and Joss said ‘This is a gas old bus, how old is she?’ – my father had said nothing.

A senior boy walked up the footbridge over the railway with us. He told us that Father Wilmot had told them that the most difficult word in the world was the word ‘being’. Then he got on his bike and freewheeled down the other side.

Joss said ‘Let’s have a look at Murphy’s house.’

‘Do you know the way?’

‘Do you not?’ They were amazed. We didn’t. My brother and I knew only the bus way home. A single turn off that and we were in the road we had seen that morning, still as empty and quiet; nobody and nothing, but the chestnut trees coming into leaf. There was the house. The front garden was full of holes where bushes had been dug up. Joss put his hands through the bars of a side gate and pulled back a bolt and we went down a cement path into a back garden: more big holes in the ground. Everything was gone except the apple trees. There were about a dozen of them, and beyond the wall a dozen more and so on up to the windows of a house as big and old as our school house, so we seemed to be in an orchard – which, we found out later, was what it all had once been.

‘Why not? Now it’s your house’, Art said and, when my brother shrugged, I was bunted up to an open fly window and shoved through like the Connaught Tribune that morning. Standing on my hands on a window ledge, I looked at them upside down.

‘Somersault. Like Signor.’

‘Sapristi!’

I fell onto the floorboards. The first thing I noticed was the smell: not nice, though not bad either – like ripe sawn wood.

‘Schweinhund! Open up.’

‘Achtung!’

‘Schnell! Schnell!’

I opened the conservatory door and we ran through the house, counting the rooms, lying in the big bath, and reading the old newspapers that lined the floors until the sky went dark. The morning forecast was coming true. Mama’s prayers has been heard again. Beyond Rathmines church dome and town hall clock tower, framed in one of the front bedroom windows, flat and black as a negative now, were my father’s shops packed with people dying for wellingtons. Thank God. There were houses everywhere, except for a space just across the road where a few fields had been spared, like a ringfort in ploughland. A small old nun followed by a sheepdog followed a cow along by a hedge. From beyond the hedge a bell rang and they all went a little faster. We looked at our watches: five to four. When Rathmines clock struck four we left, by the hall door. We delayed again at Joss and Art’s house – no one seemed to be in and now they had to get in by the side door – so it was wet evening when we finally got home.

Finding our house empty would have been like finding the Sacred Heart lamp unplugged. There they were, just like the letter above, as we had left them that morning. Yet my mother had been out, to the fields at the end of our back garden. She had got some rushes there and was trying to make a rattle for my youngest brother. Her memory had taken her three-quarters of the way. She had plaited the handle and half of the top so it was like a hood, but she could not close it over.

‘Delia –’

‘What’s that, Mrs Kenny?’ As usual when it was heavy rain, Delia came around to the fire by the long way, well away from the window. Once she had been standing under the kitchen skylight when a freak flash of lightning scorched a mark down the parting of her hair.

‘There’s some little trick to that and I remember it as well, only –’

‘Well, I never saw that done.’ Delia took the rattle and stretched her bracked shins to the fire.

‘Oh, I have it! Give it to me here till I see.’

‘Well, I could no more do that, Mrs Kenny –’ Delia turned to us. ‘Well, and what did ye learn at school? Was the master cross, tell us?’

There was so much to tell: the king of Ireland, a mouse, a house a hundred and twenty years old. But my brother was telling what Father Hillery had said about Errol Flynn –

‘Ear-roll Flynn. He has no fear of the Lord.’

‘This is the Eyetalian?’

‘No. That’s Signor.’

‘God, what’s he like at all? Has he the oily skin?’

‘They do get that from what they eat,’ Mama said.

‘Well, I was at the dance the other night, Mrs Kenny …’

‘Where?’

‘The Metropole. And if this black lad didn’t come up to me. I never saw him with the dark till he was one side of me. Well, I nearly went through the floor.’

‘‘And where was Jack?’

‘Sure, he’d gone to get me a mineral.’

‘And was he really black?’ Mama said. ‘He wasn’t one of them brown fellows?’

‘He was as black as that coal!’

‘Had he the shiny teeth?’ Mama showed her own teeth, slightly yellow like the best teeth, and then bent to nip off the end of a rush. ‘Run out in the garden and get me a few little stones like a good lad.’

‘It’s raining –’

‘May it never stop. But tell me this and tell me no more,’ Delia said. ‘The Eyetalian – can he speak English?’

‘Now look!’ Mama dropped in the wet pebbles, wove over the last little space and turned the loose ends out of sight. ‘Haven’t I the great memory. Oh, how long is it since my mother made me one of those!’

She gave it to my youngest brother on the floor, and went to ring our father. She rang him every evening, before he left work, so if business was bad she knew about it before he came home.

‘D-S-I … L-S-N …’ The shop code they used sounded like Italian. As usual it meant nothing good. She came back and got my young brother with the rattle ready for bed

‘And me sitting down!’ Delia said. As the phone rang, she sat down again. Her ear swung to the door like a compass needle.

‘… Yes, Guard … Thank you, Guard … I will, Guard.’

I knew at once. Mama came in. We had heard so she had to tell us. Some young roughs had been seen breaking into our new house. The woman next door had given their descriptions to the Guards.

Delia’s face looked anxious first, then delighted. ‘God –if the boss heard that!’

The letter flap rattled and the Evening Mail fell into the hall. In a few minutes, our father would follow. Delia built up the fire. The wireless was turned on, ready for the news and another weather forecast. We heard the key in the lock.

‘Not a word about that now,’ Mama murmured, as the door slammed shut.

The fields at the back of the house were not neat ones with nuns. From our bedroom window we saw flames of tinkers’ fires shooting up beyond the back garden wall. One day I was sitting on the wall when one of their goats jumped up beside me. He jumped after me into the garden and up the path, and when I backed against the kitchen door – locked! – he lowered his oblong yellow eyes and pressed me with his horns.

I had the same feeling now each time the door downstairs opened. Beyond the fires again were the flat orange glares of the streetlamps that fenced a new corporation housing estate. They stood in a line along a high wall topped with barbed wire, but nothing could keep out those other young roughs from the field where we played. One day they caught my brother and tied him to a tree, cut off his hair and burned it at his feet. Every day we saw the Guard, who cycled our road, stopping those gurriers with silver snot stripes on their sleeves. Now like P.C.49, he was probably pedalling slowly towards our door.

The kitchen door opened.

‘I might as well lock up and throw the bloody keys in the Liffey!’

The door slammed and our father’s footsteps came up the stairs. My brother hid his face in The Eagle. I took my new book from the locker.

‘Rosamund ran into the rectory schoolroom and closed the door behind her with the air of someone who has news to tell.

“Have you ever heard of Leonard Stone?” she demanded.

Letty and Tom looked expectant, but David did not even raise his eyes from the book.

“What is the use of asking questions when you know the answers already?” he said and went on reading. David was the only one of the rectory children who could quash Rosamund, and even he admitted that it took a lot of pressure. This time she ignored him altogether.

“If you know who he is, it may interest you to know that he is coming to live with us,” she said. “He is coming next week and –”

“But I don’t know who he is,” said Helen. She was the youngest of the family and had been promoted to schoolroom life a year ago.

Rosamund looked happier. “Leonard Stone is Daddy’s cousin’s little boy, and he is coming to live here because his father is to be Colonial Secretary in India –”

“India isn’t a colony,” interposed David.

“Well something secretary in India! His mother is a tiresome woman, who thinks of nothing but Bridge and dancing and Leonard has been left far too much with the servants, and so …”’

I began my first novel.

From the next room I heard the big double bed creak. There was a long sigh, and then silence.

— 2 —

‘Tell them all I was asking for them!’ Delia called from the hall door.

‘Don’t mind her.’ My mother bent to straighten my tie.

‘Are you right?’ The engine stopped its hysterical turning over and we backed out onto the road. This morning in the back seat there were suitcases instead of schoolbags. We stopped at the KCR and collected The Eagle. We had it half read when we stopped again outside a house in Merrion Square.

‘The Mekon!’

A small man in gold-buttoned green livery answered the door. An old woman in an astrakhan coat was right behind him, ready to go. The Mekon followed, carrying her bags. She said ‘Musha’ when she stumbled, but once she was in the front seat she had an amazing grand accent. A young woman, who looked just like her, said ‘Goodbye, mother’ in an even grander voice, and a tall hairy man in a short-sleeved dentist’s coat shouted ‘Goodbye, granny!’ in the grandest voice of all.

We went West every year, but this year, because of the house-moving, we were being sent earlier. School had just ended. Mrs Hayden told us as soon as were in the train that she had been a schoolteacher. I looked out the window: there was the one-armed stationmaster putting a rosebud in his buttonhole, just like last year. Mrs Hayden called me to attention.

‘She’s grand, only she’s one leg in the air,’ I had heard my father say, so while I listened I looked at her legs. The one-armed man blew his whistle, the train jumped forward and Mrs Hayden’s two legs flew in the air. Soon we were flying along by the canal, counting the herons, while Mrs Hayden explained everything.

‘Killucan. Kill Lucan. The church of Lucan. That’s the spire. Do you see it? Cill is the Irish for church. Are you both good at Irish?’

The train pulled out again and gathered speed and my brother said ‘Eaglais – that’s what we say at school.’

‘Eaglais.’ She gave the word a sharp long sound. ‘And that’s right. That’s the more up-to-date word. Cill is the old word, you see. Then there’s Séipéal.’ She smiled at us. ‘Have you ever heard of that word? That’s an older word than Eaglais. It’s in the middle. There are lots of words for church in Irish. Teampall is the word for a Protestant church. And then there’s another word, Ard Eaglais. That means – what do you think that means?’

‘High Church?’

‘A high church. A cathedral. We’re coming to one now. In Mullingar. I can see it from here already. I remember it being built. Well.’

By the time we reached Athlone I was as tired as if I had walked.

Mrs Hayden was only getting into her stride. ‘Ath Luain, Luan’s ford.’ She was quiet for a moment as she looked down at the powerful river.

‘Like Longford,’ I said, like a fool.

‘No no no –’

We swung right, up the bare west shore of Lough Ree. She pointed back across the lake. ‘No, that’s AnLongh Phort …’

On the left, through the other window, I could see a train steaming out for Galway. I followed its track in the map framed above Mrs Hayden’s head … turning right at Athenry, then Monivea … Tuam … up to the dent in the Mayo border where my mother and Delia and every week the Connaught Tribune came from. And now Delia was leaving, to get married, to the milkman. I had gone with her one evening to see her new home. It was somewhere in town, one big old room with a ceiling as high as our house, our old house, divided in two by a red curtain. The milkman had stayed on the other side of the curtain.

‘Knockcroghery. Cnoc na Crocaire. What would you say that means?’

When she told us the history of that, there was the clay pipe factory and that took us most the way to Castlerea.

‘We won’t feel now,’ she said. ‘Now, who do you think lives in there.’ She pointed to a thousand flying trees. ‘That’s a hard one.’

‘Who?’

‘I’ll give you one clue. The king of Ireland.’

‘Father O’Conor.’

‘How did you know that?’

‘He’s our rector.’

I glimpsed the far-off flash of windows. Maybe he was there now, looking out at our train as he wrote my school report, ending as usual ‘a trifle giddy’.

We reached Ballinlough without history or etymology. Mrs Hayden was too busy asking us questions about Father O’Conor and yawning casually at our replies and then casually summing up. ‘He could have had all that, but no. No, he gave it all up to be a poor ordinary humble priest.’

‘He’s a Jesuit,’ my brother said.

‘It makes no difference!’ Mrs Hayden said, but her eyes had the same look as Signor Agnelli’s when we stood on the rostrum and looked down at him. Nine years old but I understood, sure as Napoleon.

She looked out the window. ‘Loch O’Flynn. We’re nearly there.’

‘Loch O’Flynn,’ my brother murmured. ‘The Lake of the Flynns.’

Her ears shone red against her astrakhan collar. My brother’s eyes caught mine.

‘I hope I won’t have to speak to your aunt Margaret about you.’ She kept her face to the green blur out of the window. The train shuddered and the blur went grey and then we stopped outside a giant black-and-white sign.

‘Sorry, Mrs Hayden – Béal Atha Hamnais?’

The porter shouted ‘Ballyhaunis!’

We would hear that shout every summer for the next five years but never again with Mrs Hayden. We must have met her often when she came to Margaret’s, to ask flowers for the friary altar, but my last picture of her is going down the station path between the carts and cars, erect. When she saw who had come to collect us, her Merrion Square manners returned.

‘Give her a dart of them stoneens!’ Brod called back to us as he drove down behind her. ‘Hi! Do not!’ He pulled his head in as we scrabbled for the gravel washing up and down the floorboards. It was a little blue lorry, falling to bits. From the back we could see over the town. The train pulled out and we saw on the other platform a dozen men, each with a suitcase, standing in a line before another giant ‘Béal Atha Hamnais.’

‘Many’s the scelp she gave me in there then.’ Brod put his head out of window again as we passed the National School and attacked the hill. There was a cloud of blue smoke, and Brod went into neutral and coasted back down. Mrs Hayden went into her house without even a glance at us – racing uphill again, thirty miles an hour in second gear. Her door shut as we rolled back down again.

‘Where did you get her, Brod?’

‘Ye don’t know him. He’s Biesty. He’s a big shot below in Ballindine. Stop where ye are.’ Brod turned and went into reverse and quick as the swallows skimming alongside we flew to the top.

‘She’s slipping in third …’ He turned right ways again at the graveyard gate. Down the avenue of tombstones we could see, across a mile of bog, our train steaming towards Claremorris. We ran in neutral down a straight road through warm smoky air that plumed back our hair as we stood behind the cabin.

‘Yip yip alloi! Ben Hur!’