7,00 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: The Lilliput Press

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

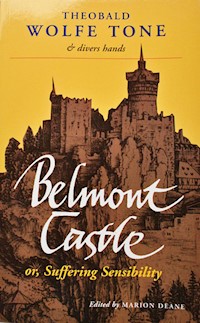

Among the possessions seized from Theobald Wolfe Tone upon his arrest in 1798 were two copies of Belmont Castle, the epistolary novel he wrote and published with his friends Richard Jebb and John Radcliffe in 1790. Much more than a mere youthful literary squib, Belmont Castle is an elaborate roman à clef, satirizing the lives of several prominent figures of the Anglo-Irish establishment and redressing a painful love affair from Tone's past. Written in a style that mocks the popular sentimental fiction of the period, Belmont Castle gives us a xenophobic Lord Charlemont, a foppish Sir Thomas Goold, a social-climbing William 'Index' Ball and 'Humanity' Dick Martin as one of several villains in a frothy tale of love and intrigue, abductions and duels, dances and dandies, blushing belles and charging rams. In a tour de force of scholarly recovery, Editor Marion Deane's introduction and annotations guide us through a labyrinth of truth, half-truth and innuendo. Deane shows that Tone composed more than half of the novel, and that the love affairs at the centre of the plot are based on Tone's own infatuation with Lady Elizabeth Vesey, and on Lady Vesey's subsequent celebrated adultery and elopement with a Mr Petrie. Belmont Castle is at once an amusing mock-Gothic novel and a fascinating historical document, shedding new light on the lives of the great and the good of Anglo-Irish Dublin in the period of 'Grattan's parliament', and on Tone himself in the years before he embraced revolutionary politics.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2015

Ähnliche

BELMONT CASTLE

or

SUFFERING SENSIBILITY

Theobald Wolfe Tone & divers hands

Edited byMarion Dean

THE LILLIPUT PRESS, DUBLIN

Handwritten inscriptions at the opening of letters VII, VIII and XXXIII—all of which are reproduced in the footnotes—gave the first clue to the authorship of the individual Letters. As a result I was able to divide them into three possible groups according to the internal stylistic evidence. The marked characteristics of Tone’s writing in his Autobiography are identified with reasonable certainty. When I established through detailed research that the character of Sir James Dashton was clearly modelled on Sir Thomas Goold, a well-known contemporary of the authors, the possibility suggested itself that the whole novel was a roman a clef. On subsequent evidence, I made the following attribution of the Letters, a decision confirmed as the correlation between the novel and contemporary events revealed itself more clearly. Thus, as can be seen, Tone wrote half the novel and John Radcliffe had the role of ‘Editor’.

ATTRIBUTIONS

Theobald Wolfe Tone: Letters—iii, vi, viii, ix, xii, xiv, xvi, xvii, xix, xxiii, xxv, xxvi, xxvii, xxviii, xxix, xxx, xxxii, xxxiv.

John Radcliffe: Letters—i, ii, iv, v, x, xxi, xxii, xxxi, xxxiii, xxxv.

Richard Jebb: Letters—vii, xi, xiii, xv, xviii, xx, xxiv.

INTRODUCTION

One may wonder whyBelmont Castlehas lain in relative obscurity for almost two hundred years. I suggest there are several reasons for this. In the first place, the only known surviving copies were in private hands until the thirties of this century. Since the cataloguing of the National Library of Ireland copy in 1935, a number of scholars, bibliographers and journalists have briefly alluded to its existence.1They were presumably seeking for evidence which would throw some additional light on the personality and career of Wolfe Tone, the most famous of its three co-authors. But they seemed to find in the novel a little more than a further example of that “execrable trash”2which its author claimed to debunk. From the point of view of the literary scholar, the novel has a mild interest as a minor example of the sentimental novel of the late eighteenth century; but it seems to offer little more than that. I, however, would like to show that the novel is a much more interesting text than these rather dismissive attitudes would indicate.

In brief, this is aroman a clef.Internal evidence, combined with the evidence from the lives of the three authors, reveals that the novel is a veiled account of events which took place within the enclosed world of several famous and interconnected families of the Anglo-Irish ascendancy. The possibility of libellous action against the authors or their publisher was raised in the one known review of the novel, printed inThe Universal Magazine and Review or Repository of Literaturein November, 1790;

Yet in candour we cannot avoid expressing our disapprobation of the almost uncharitable severity with which the Editor has treated several of the most distinguished characters both in this and in the sister kingdom … True it is, the portraits of these personages, have a strong resemblance to their originals, but as caricatures thet should be discontenanced.3

The authors exercised considerable ingenuity in assigning to their fictitious characters names which were pertinent to the reputation of the living originals. Unravelling the codes in this novel permits us to see what rich amusement it must have afforded to the Irish gentry in particular, since it draws heavily on contemporary gossip and scandal for its plot. The idle elegance of the aristocratic way of life depicted here loses some of its leisured appeal when it is viewed in the light of the injured lover who audaciously exposes the secrets of a torrid love-affair which forms the nucleus of the story. From the outset, he wonders at his “own madness” in allowing the vengeful pique he felt for the “scoundrel” husband of his beloved express itself in a manner that must of necessity “compound the debt withherhonour.”4

Tone recorded in his diary:

I …, in conjunction with two of my friends, wrote a novel.5

The emphasis is right; the text confirms him as the central contributor. Radcliffe creates background and an internal audience. Jebb fills in sketches of characters supplied by Tone and Radcliffe;6the figure of Sir James Dashton is his only unique contribution. The trio regarded the novel as an elaborate joke, accessible only to that priveleged section of the Ascendancy which could afford to laugh at the idiosyncracies and debacles of celebrated colleagues or of those who aspired to friendship with them. To make the joke effective, it was necessary to establish a code of gentlemanly propriety which would place indiscreet or outrageous behaviour in high relief. It was Radcliffe who, with diplomacy and tact, undertook to establish this ideal. He not only introduced into the novel noble personages who were venerable and illustrious in their own right; he also thereby provided the work with the nucleus of that priveleged, hidden audience which it set out to amuse.

Jebb, Radcliffe and Tone were all Trinity graduates who found themselves in London to read for the bar at the Inns of Temple in 1787. It was at this time that the joint venture of writing an epistolary novel was first mooted. Each of them had, by background and education, a cultured interest in literature and the plastic arts, in theatre, music and, specifically, in the newly fashionable Italian opera. Their original aim seems to have been to parody the popular sentimental fiction of the period, but they eventually combined this with the idea of caricaturing well-known members of their social group.

Jebb and Radcliffe completed their legal studies and later held prominent positions in the Anglo-Irish establishment. Their political and social beliefs were ultimately as widely separated from those of Tone as were their careers. So great was Tone’s hatred of the law that he apparently attended class on only three occasions. Most of his energy was devoted to an almost obsessive round of theatre and opera. References to both abound in his writings. The novel was probably planned during the early days in London, but it was not completed until the late summer of 1790, at which time the central story of the book was the theme of current gossip. In addition, incidental news items of the previous two years were woven into the text in such an amusing manner that we can assume that the audience who read it would have enjoyed its topicality and the air of authenticity created by the inclusion of such familiar material.

It is possible to prove from contemporary sources that many of the fictitious characters in the book were based on people known at first hand by one or all of the authors. The famous Mrs. Mary Delany has substantiated in her published diaries much of the petty gossip upon which they drew so freely. The trio agreed on a system whereby Radcliffe, who was closely connected by marriage to both the Earl of Inchiquin and Lord Charlemont, would embellish his contribution by barely-disguised references to known alliances, honourable and otherwise, within the social precincts of these two families; Jebb, on the other hand, would concentrate on the extravagances of a well-known dandy of the time, Sir Thomas Goold, and link the daughter of Inchiquin with his amorous pursuits. We know that Charlemont lavished praise on Goold, but the details of his infatuation with Lady Cecilia in this novel are hilariously improbable and are no more than an indication of the spirit of fun which informs it. But it is here, where Jebb departs from probability, that Tone’s contribution matters most. With great skill and a deliciopus sense of irony, even malice, he uses the personae of Belville and Scudamore to compromise the reputation of his former friends by elaborating a fiction for the understanding of which his priveleged audience needed few if any decoding skills. Tone created both the villain and the hero of the novel. Lord Mortimer, to whom the work is essentially addressed, may be regarded as the conventionally noble gentleman whose function is to retore normality when tragedy strikes. But both Belville and Scudamore are stronger, less stereotyped presences; they illustrate opposed aspects of Tone’s personality and attitudes prior to his political development in the 1790s. At first reading, the authority of Tone’s voice is disconcerting, especially for a reader who expects to find in a novel such as this the otherness of fictional impersonation. It is only when the key to the novel is turned to unlock the plot’s contemporary application that we recognise the indisputable authenticity and directness of Tone’s contribution.

From his daily reading ofThe Morning Post, Tone gathered a store of miscellaneous information which he adroitly introduces for comic effect into the novel. His gaiety and his fondness for good wine and good food, his amusement at current fads and fashions such as the cult of sensibility and its attendant hypochondria, appear in the novel as characteristic features of a priveleged and epicurean society. While particular and apposite references to persons or events connected with Lord Charlemont or Murrough, the 5th Earl of Inchiquin, are detailed in the footnotes, it is proper to mention here the general range of social references he commanded. We learn the names of artists and performers who enjoyed the patronage of these illustrious families; we hear of the new gentlemen’s clubs and the association between then and socially exclusive regiments of the army, such as the Coldstream Guards. We hear of technological innovations—the new German flute which could be broken up into sections, the new sulphur match, the growing popularity of boxing matches, the welcome given to new institutions like hospitals and the current anxiety and hostility concerning conditions in jail. In almost all instances the references apply to aspects of contemporary lfe in Dublin. This must have given his audience a pleasant shock of recognition.

The action takes place in London and its environs, but all the central characters are based on members of the Irish ascendancy or on people involved in Irish affairs. London is, in effect, a version of Dublin, and the patrician world of the two cities is represented here in ideal terms as the centre of high civilisation. The enhanced national feeling, pronounced since the achievement of parliamentary independence for Ireland in 1782, blended very easily with the repudiation of continental customs and habits which had become more marked in England in the seventies and eighties. The growing distaste for theGrand Touras a threat to native English morality was, for instance, carried over into this novel in the opinions attributed to Mortimer, who avows himself relieved to have left behind the “tinsel” manners of the French and the licentiousness of the Italians and to have returned to the more austere morality of the British system, where the chastity of women like Juliana and Georgiana was esteemed and cherished. Lord Charlemont was known throughout his life to have expressed repugnance for the French.7William Ball, alias Belville, condemns the profligacy of young men who had travellesd abroad. But the so-called contrast between foreign licentiousness and native morality is treated ironically in the novel. Male characters pay lip-service to the exquisite sensibility and delicacy of maidens while they themselves are having intrigues or affairs with “sultanas” or “married women” and are simultaneously plotting to violate the virginal innocence they pretend to admire. The wicked impulses may be ‘foreign’ but the double standards of the returned aristocratic play-boy are native. This ironic element in the novel is of particular importance in the appreciation of the rather astonishing, even shameless, flamboyance of Tone’s treatment of the spurious virtue of the heroine who is depicted as a chaste flirt, provoking in the villain’s mind the very thoughts she is meant to abhor. Frequently the women who protest against intended assaults are presented as ambiguously weak and implausible in their denials.

Tone’s declared intention was to write a burlesque8of the prevailing sentementalism of contemporary fiction. But this original motive was replaced in time by a desire on his part to exact retribution in the wake of a revived but ultimately failed love-affair. Much of the incidental material of the novel was garnered over a two-year period but the central scandal, which supplied the central plot, was only two months old in 1790. In order to humiliate a man whom he detested, he was prepared to expose, in the most uninhibited manner, the wiles, the absurdities, the debacles of his own infatuation with Lady Elizabeth Vesey, the model for the disreputable wife of the story, Lady Elizabeth Clairville. The novel is, therefore, a curious document in which literary parody and caricature are used to expose a series of events well-known to its potential readership. Before detailing this further, it is necessary to say something about the authors and the known history of the text.

THE HISTORY OF THE TEXT

When Tone was taken prisoner off the warshipHocheat Letterkenny, two copies ofBelmont Castlewere among his confiscated effects. Along with these there waws also a copy ofThe Trial of Hurdy Gurdy, a bitter parody on the savagery shown by the judiciary to the United Irishmen, written by Tone’s in-law, William Sampson and published in Belfast. One can only imagine the dismay with which Tone, during his lonely exile in Paris, read of Tallyho Turncoat or Tyrant Caliban, as they bullied and tormented the eponymous revolutionary hero who cried out against them:

The kings of the earth have gathered to- gether and have taken counsel against me, but in the name of the Lord, I will defy them.9

The third article confiscated was his own pamphlet,Address to the People of Ireland, referred to in his Journal, November 1-2, 1796:

I have been hard at work here on an address to the people of Ireland, which is to be printed here [i. e. Brest] and distributed on our landing.10

The books make a poignant contrast. The revolutionary literature to be expected of a political leader consorts oddly with thejeu d’espritof only six years earlier.

The distinguished bibliographer, M.J. MacManus, has provided an authentic provenance for the two copies of the novel. The militia which arrested Tone at Lough Foyle was led by a prominent Letterkenny landlord, who had been a contemporary of Tone at Trinity College. In 1939, MacManus bought at an auction one copy of the book, bearing the bookplate of John Boyd, the arresting sergeant. This had obviously been in Boyd’s library since its confiscation (or, strictly speaking, its theft). With it were the copies ofThe Trial of Hurdy GurdyandThe Address to the People of Ireland, on the first of which was inscribed, in Boyd’s handwriting,

I took these two off the Hoche

The second copy of the novel has a signature by Boyd, which matches the handwriting in the sentence quoted. It somehow made its way, (with no recorded intermediary), into the possession of the famous bibliographer, E.R. McClintock Dix, by whom it was bequeathed to the National Library of Ireland in 1935. This is the copy reproduced here.

The original is an average cut copy measuring 67/16” x 37/8”, probably issued in the drab, slate-grey wrappers favoured by Byrne and other Dublin printers of the time. It consists of 6 unsigned leaves, B to K in ‘twelves’ and L. 6 leaves. In both copies there are notes in pen by unknown hands which describe chapter 7 as a portrait ofT. G—-dby Jebb; chapter 8 as a portrait ofJ.W. B—lby T.W. Tone, and chapter 32 as having been written by Radcliffe. This information enabled me to assign the various chapters to the different authors and to develop an account of the novel’s background.11

Dix (1857-1936), as a great bibliographer, private collector and cataloguer, was a pioneer in the field of Irish bibliography. He listed Irish printers and their publications from the seventeenth century, motivated by the desire “to have some record of our local literature in case the books themselves should be scattered.”12In part VI of his manuscript catalogue of his own library,Dublin Printed Books of the Eighteenth Century and Some Uncertain Dates, now in the National Library, Tone’s novel is listed on page 11:Belmont Castle or Suffering Sensibility. Founder and first president of the Bibliographical Society of Ireland in 1919, Dix was an authority on the Dublin printers of the eighteenth centiry. From him we can gather more information about this novel. A family of printers, James Byrne and his son Patrick, can be traced through their various premises in Dublin from 1749. Patrick seems to have more than a professional acquaintance with Tone. When Tone wrote his pamphlet advocating neutrality for Ireland in the war with revolutionary France, Byrne rejected it and was roundly cursed by Tone for his pains—”for which his own gods damn him!”13

Yet in 1790 he was willing to risk the publication ofBelmont Castle, in spite of the threat of libel which it posed. In November 1790, an unknown critic warned the Dublin audience that

despite the pleasure his pen affords us, our humane feelings should exert their monitory voice and check our transports.14

Many biographers of Tone thought this review a fake, a mere trick on the part of the authors to gain attention for a colourless novel. But the evidence indicates that there was indeed a reason to encourage the exercise of a “monitory voice” of “our humane feelings” and that the risk of an action was real. It is probable that the review was written by Tone himself. Byrne’s shop, from 1784, was at 108 Grafton Street, near to the house of Tone’s in-laws and next door to the Irish Academy House. Frequented by Tone, the Academy also included Lord Charlemont and William Ball, both of who figure in the novel in disguised form. When Tone was a law student in the Temple in London, he reviewed regularly for Byrne’sUniversal Magazine and Review. His contributions, which I shall deal with in more detail later, were anonymous and are difficult to identify. But one can only wonder at the tenacity of a printer who offered Tone’s later political pamphlets to the public and, according to one anecdote recorded by Tone, had to listen to denunciations from powerful figures such as Lord Cavendish, who came into his bookshop to administer his rebukes while Tone hid behind the bookshelves. On another occasion, in May 1795, Lord Mountjoy reported that, on his last day in Dublin, he saw Tone in Byrne’s shop.15Perhaps Byrne was indebted to Tone for boosting his sales of popular fiction through the reviews he provided of novels which he would have had the benefit of reading in earlier London editions. But there was obviously a political bond between them as well. TheHibernian Journalfor April 1793 records that 21 Defenders were sentenced to death and that one Patrick Byrne was fined 1,000 pounds and inprisoned for two years for circulating Thomas Paine’sCommon Sense.16(This happened just after Byrne’s chimney had collapsed, causing damage to the Academy building.)

The fact that Tone hadBelmont Castlewith him on his fateful expedition to Lough Foyle might indicate that he had an especial fondness for the book and even for the life of a leisured man of letters which he had abandoned for politics.17Yet the novel itself contains within it, or within those parts of it written by Tone, signs of his ambivalent position in Anglo-Irish society. His letters expose that society’s pervasive self-deception. The intimacy with the lives and loves of the gentry, as revealed in the novel, is countered by the fact that the characters he introduced—Belville and Scudamore—are also outsiders, men who do not quite belong to, though they are closely involved with that society. Belville, like Tone, has been “contaminated by trade”18; he does not belong to the landed gentry, and Tone’s presentation of him suggests that there is something contemptible and absurd in the pretentions of the great and in the efforts to gain entry into fashionable society by submission to their principles. Belville is modelled on William “Index” Ball, a man who embodied much of what Tone admired, while Scudamore is unmistakably modelled on Tone himself, the raffish youth of Trinity and the Inns of Court. Both of them are, in an important sense, outsiders. Both die—one killed by a Lord in a swordfight, the other by suicide. Had their love-affairs been successful they would have gained entry into Society. But that is not permitted them. Still smarting from the after-effects of his affair with Lady Vesey, rendered more painful by the public scandal of her new relationship, Tone seems to have seized the opportunity to expose the hypocrisy and double standards of fashionable society. His unease about his own position in it is in marked contrast to the idealised versions of it given by his two co-authors, Radcliffe and Jebb. This contrast becomes stark in later years. Tone became the most famous of Irish revolutionaries while they became respected and increasingly conservative members of the Anglo-Irish establishment.

RADCLIFFE

According to Francis O’Kelly, Radcliffe’s name was not included in theCatalogue of Eminent Middle Templars, even though he was Judge of the Prerogative Court in 1816. He implies that nothing else is known of him. Such is not the case.

Radcliffe’s connections with the Charlemont and Inchiquin families are bewilderingly complex and are best pursued through the intricacies of Lodge’sGenealogies of Ireland and Great Britain.19It does seem that he had actual blood connections, although distant, with the leading aristocratic families. There was a direct, if remote, descent from the Watson family, on his mother’s side. His mother’s and his wife’s relationships with the O’Briens, the Caulfields and the Watsons can be ascertained from an examination of several family pedigrees. These suffice to establish a close intermarriage acquaintance with the most accomplished and prestigious characters within the novel and to validate the claim he makes in his editorial address, that he had at least a glimpse of his illustrious audience in domestic retirement.

He married Catherine Cox in 1787. Her father, the Reverend Michael Cox, Archbishop of Cashel (1779) had previously been married to Ann O’Brien, cousin of Murrough, the 5th Earl of Inchiquin. Her brother, Sir Richard Eyre Cox, was connected to the same family by his marriage to Maria O’Brien, the niece of Inchiquin (c.1784). Her grandfather, Sir Richard Cox, “a most intelligent, well-informed gentleman” was recommended by Charlemont for his “correspondence in 1878 with Sir Lucius O’Brien, in which he displays a perfect intimacy with Irish affairs.”20

Radcliffe’s own mother was daughter to Robert Mason, who was a direct descendant of the Watson line of the Marquis of Rockingham’s family. The Dublin Almanack of 1787 records that the senior members of the Jebb, Radcliffe and O’Brien families were engaged in voluntary work, supporting Dublin schools and charities.21This is worth noting because, in the novel, the penitent Scudamore is moved to make his final bequest to a hospital for “poor, decayed and gouty men” (presumably Simpson’s Hospital in Great Britain Street).

When Catherine’s step-mother died in childbirth, Mrs. Delany commented that she was “much lamented by everyone”.22Catherine’s cousin, John Eyre Cox, had a daughter, Mary who married Francis Caufield, brother to Lord Charlemont. The tragic circumstances of this family’s death was one of the first and strongest indications of the novel’s indisputable and pervasive references to Charlemont. His brother had just left London on the 9th. November, 1775, to take his place in the Irish Senate. He was accompanied by his wife and daughter and an “infant 3 years old.” They all perished in a storm outside Dublin. Their ship appears to have gone down at Parkgate, coming up the river to the port.23

This 3 year old is resurrected in the novel as the orphan Juliana, the beloved of Mortimer. Mortimer is himself an idealised portrait of all that is best in the family history of the Caulfields and the O’Briens. His marriage to Juliana, which breaks the family’s traditional opposition to marriage to anyone socially inferior, possibly owes something to the well-known sponsorship by Sir Lucius O’Brien of Charlemont’s own marriage to Mary Hickman whose sister Charlotte had married Edward, the brother of Sir Lucius.24

Mortimer’s name, career and ancestry are based on those of Murrough, the 5th Earl. Both find it necessary to adjust to the unexpected acquisition of great wealth. However, Mortimer’s literary tastes and his hostility to the seductions of foreign travel reproduce the recorded opinions of Charlemont. Radcliffe paints the latter and the “good old Earl” as virtually without fault. Only the merest trace of a fashionable sensibility detracts from Mortimer’s characteristic steadiness and good sense.

When Radcliffe, through Juliana, describes the decor of her London home, the detail is remarkably similar to Mrs. Delany’s description of her arrangement of books, her china and the chenille work on her chairs at Delville. Lord John’s (i. e. Charlemont’s) house in Grosvenor Square had an “ante-chamber hung with delicate silk, the chairs matching the hangings with a delicate lilac silk … finest porcelain … and a book-case stored with our choicest English china.” The variety of “spruce villas, humble cottages, rich woods, smooth lawns, lofty towers and glittering spires” which delights Juliana’s eye, is almost a mirror image of “the crocketed pinnacles, thick woods, moss houses, rustic hermitages and rural alcoves”25which diversified Charlemont’s demesne at Marino. Juliana, whose surname is Blandford, is introduced by Radcliffe with an apology for the “very imperfect” story he has of her. The phrase is a verbatim reproduction of Mrs. Delany’s comment on a certain other Miss Blandford who, like our heroine, brings to her marriage an identical “jointure” of “three thousand pounds”.26

Tone praised the letters written by Radcliffe inBelmont Castleas “far the best”.27This is debatable. Certainly Radcliffe had a flair and elegance which transformed the fairly mundane material with which he had to deal along with a certain skill and grace in disguising his borrowings. There is a pertinent anecdote about his grandfather, Stephen Radcliffe, Vicar of Naas, who had been at the centre of a row for having dared to criticise a lecture given by Dr. Edward Synge onThe toleration of Popery, delivered at St. Patrick’s Cathedral. The argument itself is not of interest here but rather the vitriolic abuse which Stephen Radcliffe’s writings received. They were attacked as the “senseless, dull, insipid and ill-natured” works of an author “if [I] may pardon the expression”. Apparently his adaptation of quotations fromThe Faerie Queene(Book I, Canto IX, Stanza 43) were so “altered in expression and sentiment” that one could “scarce know it in disguise”.28John Radcliffe may have imitated his grandfather’s technique of the interwoven quotation from established authors, but he was certainly more subtle and successful in his use of it.

John Radcliffe’s father had been a clergyman whose early death in 1766 may explain why, an only child, he was moved at a tender age from Fermanagh to Drogheda. In his schooling there under Dr. Norris he must have begun his life-long friendship with Richard Jebb. It has already been established that the senior members of these families were part of a wealthy philanthropic community in Dublin. Unsurprisingly, schools were among the main beneficiaries of their generosity.

John’s father had two brothers who became judges. It is not, therefore, surprising to see him become Judge of the Prerogative Court. Family precedent and perhaps family influence as well as his own personal ambition and achievement would have led him naturally in that direction. This appointment had been formerly made by the Crown. It was then delegated to the Archbishop of Armagh, so that the Ecclesiastical Court and the Prerogative Court were a single body, holding their meetings either in the Judge’s own house or in the Chapter Room of St. Patrick’s Cathedral.29As a consequence, there was no secure custody for wills and records. When Radcliffe took over as Judge, he provided a building and transferred original documents to Henrietta Street where they remained until they were moved to the Public Records Office and currently to the National Library of Ireland.

Thus it is clear that Radcliffe had several lines of connection with the Charlemont, O’Brien and Wentworth families and would have had intimate knowledge of or access to some of the family history upon which the novel draws so freely. His professional and literary background is a natural setting for the young trainee lawyer who undertook, on this one occasion, to become an author.

JEBB