7,19 €

Mehr erfahren.

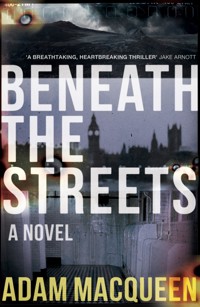

- Herausgeber: Lightning Books

- Kategorie: Krimi

- Sprache: Englisch

When Jeremy Thorpe hired thugs to kill his ex-lover, they botched it. What if they had succeeded? 'A breathtaking, heartbreaking thriller' - Jake Arnott LONGLISTED: Polari Prize It is February 1976, and the naked corpse of a shockingly underage rent boy is fished out of a pond on Hampstead Heath. Since the police don't seem to care, twenty-year-old Tommy Wildeblood - himself a former 'Dilly boy' prostitute - finds himself investigating. Dodging murderous Soho hoodlums and the agents of a more sinister power, Tommy uncovers another, even more shocking crime: the Liberal leader and likely next Home Secretary, Jeremy Thorpe, has had his former male lover executed on Exmoor and got clean away with it. Now the trail of guilt seems to lead higher still, and a ruthless Establishment will stop at nothing to cover its tracks. In a gripping thriller whose cast of real-life characters includes Prime Minister Harold Wilson, his senior adviser Lady Falkender, gay Labour peer Tom Driberg and the investigative journalist Paul Foot, Adam Macqueen plays 'what if' with Seventies political history - with a sting in the tail that reminds us that the truth can be just as chilling as fiction. 'A fucking fantastic read. A gripping what-if thriller, packed with vivid period detail and page-turning twists. To find myself actually making an appearance in the final chapter was just cream on the cake' - Tom Robinson

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2020

Ähnliche

Published in 2020

by Lightning Books Ltd

Imprint of EyeStorm Media

312 Uxbridge Road

Rickmansworth

Hertfordshire

WD3 8YL

www.lightning-books.com

Copyright © Adam Macqueen 2020

Cover by Ifan Bates

The moral right of the author has been asserted. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Printed by CPI Group (UK) Ltd, Croydon CR0 4YY

ISBN: 9781785631733

For Michael. For everything.

Many of the characters in these pages, from pimps to peers of the realm, share their names and certain biographical details with real people.

That is all they share.

What follows is a work of fiction.

Contents

ONE

TWO

THREE

FOUR

FIVE

SIX

SEVEN

EIGHT

NINE

TEN

ELEVEN

TWELVE

THIRTEEN

FOURTEEN

FIFTEEN

SIXTEEN

SEVENTEEN

EIGHTEEN

NINETEEN

TWENTY

TWENTY-ONE

TWENTY-TWO

TWENTY-THREE

TWENTY-FOUR

TWENTY-FIVE

TWENTY-SIX

TWENTY-SEVEN

TWENTY-EIGHT

TWENTY-NINE

THIRTY

THIRTY-ONE

THIRTY-TWO

THIRTY-THREE

THIRTY-FOUR

THIRTY-FIVE

THIRTY-SIX

THIRTY-SEVEN

THIRTY-EIGHT

FOUR MONTHS LATER…

THIRTY-NINE

FORTY

FORTY-ONE

AFTERWORD: TRUE STORIES

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

ONE

Some people dream of retiring to a cottage in the countryside. Me, I have to settle for a cottage underneath the pavements of Soho.

It was dark, like it always is. As fast as the council put new bulbs in, the punters take them out. The street light from above made it just far enough down the stairs that you could make out the stern notice: No Loitering – Please Adjust Your Dress Before Leaving. Someone had vainly tried to scrub out the question marker-penned on the tiles below it: What if I’m not wearing one today? As I descended, the familiar fug rolled out and filled my nostrils: the ammonia sting of piss with an undertone of something else, the rich, hot, masculine scent of secrecy and sex.

The urinal closest to the entrance was free, and I took up position there until I could work out what was what. Flopped it out for appearance’s sake, but didn’t even try to go. I hadn’t had as much as a cup of tea since breakfast time, and knew I needed to save what few drops I might be able to squeeze out as evidence if the police came clattering down the steps, like they did increasingly often these days. What, me, officer? I’m just minding my own business and having a piss, as you can clearly see.If you wouldn’t mind letting me finish I’ll zip up and be on my way. Word is that the law says that as long as its pointing downwards not upwards they have to let you go, but I wouldn’t put money on it. In my experience what a policeman actually sees and what gets written in his notebook bear very little resemblance to each other. And a magistrate will only believe one version, and it won’t be the one you remember.

The old geezer standing next to me lost no time in checking me out, shuffling across for a better view and even reaching out an exploratory hand, but I batted it away without any trouble. I could tell by the wrinkles and liverspots on the back of it he must be seventy if he was a day. He wasn’t what I was looking for.

With my eyes beginning to adjust to the gloom I could see we had a full house: every urinal taken, the cubicles fully occupied by the sound of things, and a couple of blokes hanging around the sinks, one washing his hands over and over and the other stood by the hand towel, giving it a yank down to make the drum spin and screech every so often just for appearance’s sake. But the longer I lingered – getting close to half-mast; I can’t help it, these places have that effect on me – I could see that the place was working like a relay race: no sooner would one of the doors behind us bang open than one (or, if he was lucky, two) of the men in the row beside me would peel away and go in to the vacated cubicle; instantly one of the blokes at the sinks would step in to take his place, all of it working like clockwork, with never a word said or a beat missed. The randy old git soon started chancing his arm again, so when a vacancy opened up three stops down the line I stepped out and nipped into it, not even bothering to do up my trousers. The compulsive hand-washer had started for the gap at the same time, but he had more distance to cover on the puddled and treacherous floor. He let out a tut of frustration and diverted into the space I had just left, but he obviously didn’t fancy Methuselah much either because within a minute he’d zipped up and gone back to his Lady Macbeth act.

Meanwhile I’d had the chance to check out the view to either side. The bloke on my left was a burly labourer type, or at least that was how I filled in the gaps in my peripheral vision, with an impressive erection that he was working up all by himself, close to what looked like the point of no return. To my right was a middle-aged chap in a business suit, nervously sucking on a cigarette and playing with a cock that was as thin and unimpressive as he was. I could tell from the jiggling pinstripes that he would be home within the hour, taking off his jacket in a hallway in Surbiton or Orpington or one of those other places that only exist as names on railway departure boards, making excuses to his wife about broken rails or ASLEF go-slows while she fetched him his gin and tonic and told him what a poor hardworking dear he was. I’d been with plenty like him when I was still on the game. A suit and a decent pair of shoes usually meant they were good for the money, and not likely to turn nasty, because a scene in public could harm them more than it could you. But that wasn’t why I was here tonight – I don’t do that any more – so when he pointed both his prick and a pleading expression in my direction I just turned and stared straight ahead, with an occasional cautionary glance stage left to make sure my jeans were well out of the range of what was about to erupt at any second. They were new, genuine Orange Tab Levi’s from Kensington Market. You’re not supposed to wash them ever, so I wasn’t about to have some stranger spunk all over them after I’d only had them a few days. Especially if it wasn’t even me making it happen.

The City Slicker wasn’t giving up, though. He abruptly went no hands to fumble in the pocket of his suit, pulling out a packet of fags and offering them in my direction. I thought about it for a second – didn’t want him feeling I owed him – but ended up taking one anyway. So did the bloke on his right, and when the suit leaned over to light it for him (gold lighter, very flash) the flame flared up and illuminated his face and I knew straight away I had found what I had come here for.

Blond hair, parted in the middle and hanging down as far over the collar of his work jacket as I guessed his bosses would let him get away with. Big, full pouting lips like Richard Beckinsale. And dark eyes that for just a moment before the flame was snapped out, had caught mine. Which meant the game was on. This was the man I was having tonight.

And my luck was in. I hadn’t taken more than two drags on my fag before the workman on my left finished what he was about, flicked whatever hadn’t already made it that far in the general direction of the urinal and thumped off up the steps without even washing his hands. I sidestepped into the space he had left, careful as to where I was putting my feet, and to my delight the pretty boy slid swiftly round the back of the city gent before he could realise what was happening and parked himself in my place, grinning across at me with a delighted smile that could break a heart softer than mine.

‘All right?’ I whispered.

‘Yeah, I’m all right, are you?’ he hissed back.

I looked down. He was more than all right. A sudden coughing fit overcame me, shattering the quietness of the cottage, and alarming the man on my left so much that he buttoned up and scurried off up to the street quick sharp. It didn’t matter: another figure was already thumping down the stairs to replace him, having to turn his bulky form sideways on the stairs so the escapee could squeeze past. I gave him a quick glance of acknowledgement as he took up his place beside me, but my attention was all to my right. My new friend had reached out an arm to slap me on the back when I started coughing, but as I recovered he let it slide down to rest half in and half out of the waistband of my jeans while his other hand came round to grope at the front of them.

‘Too strong for you?’ he whispered with a grin. He might have been talking about the cigarette, or he might not.

I looked him straight in the eye and shook my head. ‘I can take it.’ His grin widened.

One of the cubicles had come free, its door hanging invitingly open. I jerked my head in its direction, and he nodded. We tossed our barely-touched cigarettes into the urinal to fizz out together – suit man must have been furious – and went inside.

The stench of sex was even stronger in there. These must be some of the least crapped-in toilets in the whole of London, though I doubt the cleaners prefer what they have to mop up instead. He pushed me ahead of him as we went in, my knees running up painfully against the lavatory pan, but as he slammed the door to I managed to twist round so we were facing each other, stretching out my own arm to double-check on the lock at the same time.

One elephant.

His mouth was on mine, open, his hot tongue searching for a way in. I could feel his end-of-work-day stubble scraping against the smoothness of my own chin.

Two elephants.

I reached down with both hands for my belt buckle, fumbled it open. With my flies already gaping, my trousers should have plummeted straight for the floor, but I was reckoning without my new bellbottoms: they were so tight on my thighs that they just rumpled up there and I had to reach down with the one hand I wasn’t keeping on the door to try to force them further. I loved the way they looked on, but I had to admit they were not the most practical outfit for my current activities.

Three elephants.

He mistook what I was reaching for and started grinding his crotch into mine, which I must admit distracted my attention for the space of elephants four and five. Finally I managed to get my jeans down to my ankles, where they engulfed my plimsolls and pooled out over the damp floor. Looked like I was going to have to wash them after all.

Six elephants, and at last he detached from my mouth with an audible pop and a gasp. But no sooner had he taken in some air than he transferred his attention to my neck, kissing and sucking at it like a man possessed while presenting me with a mouthful of feathercut I had to twist my head to avoid. Christ, he was trying to give me a love-bite. Did he think we were dating or something?

Seven elephants.

His own trousers, brown flares made out of some sort of polyester you could barely get a grip on at all, thankfully didn’t suffer the same design fault as mine. They slipped down easily enough, and his Y-fronts went with them.

Eight elephants.

He was still stabbing insistently and fleshily into my own crotch and it was time to give him what he was looking for. I squirmed around, pushing my own pants down as I did so and arching my back and pushing my bare arse into him until he was pressed right up against the cubicle’s wall. My own forehead was braced against the cold surface of the partition opposite. It felt sticky. I tried not to think about that.

Nine elephants.

He gave a gasp as I reached behind me with my left hand and took his cock in a vice-like grip, guiding it inexorably towards where it wanted to go, at the same time reaching out my right hand to flick open the lock on the cubicle door.

Ten elephants.

The door was booted in and a blinding bright light bathed us both for a fraction of a second, leaving the darkness afterwards more black than ever before. I could feel him go rigid, but I kept a firm grip on the part of him that had been rigid already, bracing my own legs so he was pinned where he stood. Besides, there was nowhere for him to go as the flashbulb went off again, and again, and a fourth time for luck: the figure in the doorway was so vast he filled it entirely: the wall behind offered no escape bigger than the four-inch gap at the bottom or the glory-hole drilled by the bogroll dispenser. Unless he fancied flushing himself down the toilet itself, he was well and truly trapped.

‘Mr Terry Hopkins? Of 32 Leominster Gardens, NW9?’ The photographer spoke in a brisk, businesslike voice. From behind him came the sounds of a stampede as the cottage was vacated.

‘Wh-what?’ Hopkins was literally shrinking as he spoke. I let go of his rapidly deflating cock and turned sideways to yank up my trousers, taking my time with my belt buckle so I didn’t have to look in his direction.

‘Apologies for startling you, but I’m afraid it was necessary.’ The fat man tapped his camera and stood aside to let me slip past him and out of the cubicle, heading straight for the stairs. ‘Your wife’s solicitor will be in touch in a few days.’

I didn’t look back as I surfaced into the sharp cold of the winter evening. Women and men in hats and scarves milled along the pavement. A bus blasted past, its steamed-up windows aglow, commuters packed inside as tight as pilchards. I turned to my right and set off at a brisk trot, wanting to put as much distance between myself and Mr Terry Hopkins of Leominster Gardens as I could. In the Shakespeare’s Head the drinkers were knocking back their pints obliviously; two separate worlds of men, both seeking out companionship, comfort and an escape from the daily grind, separated by just a few feet of concrete and the width of the world. The punters from the cottage had surfaced and dispersed back into anonymity, swallowed up by the city. At street-level we can all pass for ordinary men.

I hurried under the big sign I had been so thrilled to recognise when I first came to London a few years earlier: Carnaby Street Welcomes the World. The shops were all shut, their interiors darkened, their frontages, once so fresh and exciting, now faded and worn. The brightly coloured patterned paving was blotted with piles of black rubbish bags awaiting collection. Welcome to London, 1976: try swinging if you must, but you’d better beware of the consequences.

TWO

Harvey met me in the doorway on the far side of Lord John like we’d arranged. He was out of breath, his camera bumping against his chest on its strap as he waddled along. His coat was flapping open: there was no need to hide it now.

‘Well done, nice job,’ he wheezed as he drew up. ‘Those’ll come out perfect.’

‘Just watch how hard you kick the door next time,’ I muttered. ‘Few inches further over and you’d have taken my head off.’

He shook his head. ‘I thought you were positioned perfectly. The perfect composition for a compromising position.’

I think he meant it as a compliment, but I wasn’t in the mood to take one. ‘Can I just get my money, please?’

Harvey doesn’t like carrying cash when he’s out on jobs like these – he’s under the mistaken impression that even the most desperate cottager would go anywhere near his trouser pockets – so we had to go back to his office on Denmark Street before he could pay me. I tried to keep a few steps behind him as we walked through Soho, in spite of how slowly he huffs and puffs along. I didn’t want people thinking we were together. Anywhere else, we might have been mistaken for father and son. On these streets, people would assume something even worse.

The shops on Carnaby Street might have closed for the night, but a few blocks east the businesses were only just starting to get going. As I followed Harvey’s broad back through the narrow streets, the competing neon turned him into a chameleon, bathing his beige mackintosh and bald pate in alternating shades of pink and yellow, blue and green. Enticement was everywhere as we passed: Erotic Escapades; Striptease Spectacular; Non-Stop Live Revue; Love Shop & Cinema; We Never Close! The girls in the doorways called out to Harvey as he waddled by, holding up an apologetic hand and firing the occasional ‘maybe another time, darling’: they took one look at me and knew better than to bother.

I’d been working for Harvey for a year or so now. I started when I was still doing rent, but quickly realised he would pay me more for not having sex with married men than they would for having it. All right, it’s not what most people would call honest work, but there’s not that many openings out there for someone who left school before they could get any qualifications and whose only experience is four years selling his arse on the Dilly. I have to settle for what I can get. Story of my bloody life.

Only trouble is it’s not regular work – Harvey only needs my services once every few weeks. He’s got two or three women on his books too: calls them the honeys in his honeytrap and pays them twenty-five quid a pop to my twenty, which isn’t exactly fair since they don’t take the same risks I have to. All they’ve got to do is sit around in some hotel bar and do their seducing in plain sight, with drinks bought for them and no risk of getting arrested in the middle of it. Trouble is, there’s no trade union for my particular line of work, and plenty of younger, prettier boys who’d be only too eager to take the work if I called myself out on strike. Still, twenty quid is twenty quid, even with prices shooting up the way they are. It all helps pay the bills, as they say, or at least it would if I was stupid enough to settle down anywhere long enough for any bills to find me.

To be honest I don’t think this is exactly what Harvey hoped he’d be doing when he went into the private detective business either – I think he had something more in the Mickey Spillane line in mind – but divorces are pretty much his bread and butter, along with tracking down the odd small businessman who’s done a flit owing money to someone bigger. If some drop-dead dame actually did walk into Harvey’s office saying she’d been framed I think he’d probably fall off his chair in surprise.

I know what you’re thinking. Don’t I feel sorry for the men? Well I don’t know, do you feel sorry for their wives? It’s not like I’m putting the idea in their heads for the first time – the way it works is that the wife comes to Harvey with a pretty strong suspicion of what her husband’s up to, and then he spends a couple of days following them to make sure before he calls me in. Apparently Terry Hopkins was a regular in every cottage within walking distance of the shop he worked in on Regent Street. Harvey had watched him do the full circuit in his lunch-hour two days running, and even pop out for a quickie on his tea break.

Besides it’s not like we’re the only ones at it: the plod seem to be sending their prettiest young coppers round the cottages more and more now to flash their crown jewels about, and then pile in mob-handed the second some poor sod takes the bait. I suppose it’s easier than trying to catch any real criminals. Not to mention the fact that half of the rent boys in London specialise in blackmailing their clients: no sooner have they got your trousers down than they’ve had your wallet out of the pocket and are reading you the address off your driving licence and promising to pay your wife a visit unless you pony up regular payments to keep them quiet.

Not me, I hasten to add. That was never my game. Pay up and you got the goods as advertised, that was the way I always played it. More fool me, probably.

Anyway, perhaps if they don’t like it, they shouldn’t have got married in the first place. They’ve had their chance at having it all – the normal life, the wife, the kids – and it’s hardly down to me if they decide to throw it all away. Some of us never got to choose.

I always knew I was never going to go that way. They say some people are born gay, some get turned gay and the really lucky ones get gayness thrust upon them, but with me it was definitely the first one. I can’t remember a time when I didn’t feel different. Preferring Ilyia Kuriakin to Napoleon Solo but not being able to explain why. Sneaking my mum’s catalogues up to the bedroom to look at the pants and vests. By the time the rest of the boys at school were picking up guitars and trying to be John Lennon, I knew I was more interested in what I’d like to do to George Harrison.

Of course then I thought I was the only one. You didn’t get homosexuals in Berkshire. Still don’t, I shouldn’t think, at least not if you asked my family. You used to hear grown-ups saying the odd thing about men who were ‘a bit funny’ or ‘got done for interfering’ – my ears would always prick up, but I quickly learned that asking questions got you told off and made your ears burn with a special sort of shame that you couldn’t explain or understand.

Thankfully I’d long since grown immune to all that. These days there wasn’t much that could shock me: I scarcely even turned my head to look at the windows of the various ‘Love Shops’ and 24-hour-cinemas we passed on our zig-zag route through the Soho streets. With just one exception: as we passed under the Pillars of Hercules I slowed down and peered enviously into the side-windows of Foyles, planning my visit for first thing tomorrow when I had Harvey’s cash in my pocket.

I love books. Always have done. ‘Always got his nose buried in a book’, the teachers at my primary school used to say. They couldn’t see that I didn’t have much choice: if you weren’t the sort of boy who liked football and British Bulldog, you were pretty much ostracised and had to make your own entertainment. I must have ploughed through every single book in the Book Corner at least twice. Even the Illustrated Children’s Bible. The dinner ladies used to joke about me having a vocation because I spent so many playtimes studying it, and not one of them noticed that it was always the page with Jesus stripped of his garments.

Nothing’s changed in the years since. I’ve still always got a book on the go. The other lads on the Dilly would take the piss out of me because I always had a paperback in my pocket: the Bookworm, some of them used to call me, but it never really caught on.

Foyles is my favourite place in the whole of London. You can lose yourself in its crazy rabbit warren of shelves for a whole day if you keep moving and avoid the assistants, and finish a whole book in the warm and have it back on the shelf by closing time without anyone being any the wiser. It’s easy to lift them too, at least the paperbacks, which will slip into a jacket pocket or down the back of your trousers if your coat is long enough: that way you can finish them at your leisure and the second-hand shops on the other side of the road will always give you a few pence for them when you’re done.

Harvey was crossing Charing Cross Road now, and I hurried to catch him up as he headed into Denmark Street where he has his office. Harvey Lewenstein, Private Investigator says the brass plaque by the door, but you’d have to be looking for it to spot it: it’s the shabby side door of a guitar shop and his actual office is right up in the attic. The middle floors are rehearsal rooms, which means there’s usually some kind of racket going on whatever time of day you visit, but tonight’s was the worst I’d heard yet. It sounded like the group had decided to attack their instruments rather than play them, or maybe attack the singer with them, given the strangulated yelps he was emitting.

‘Tell me about it,’ muttered Harvey once we were clear of the first landing and could hear ourselves speak. ‘Bunch of filthy beggars they are, in and out at all hours, leaving the front door wide open. And I think some of them might be staying overnight. Need to have a word with the landlord.’ At that point climbing the stairs became too much of an effort for him to talk as well, and we went up the last two flights accompanied only by his asthmatic wheezing and the considerably less rhythmic thumping of the drums.

He made a great palaver of unlocking his office door, which actually does have a glass panel with his name engraved on it – ‘It’s what the customers expect,’ he told me crossly when I laughed at it on my first visit. Sadly that’s where any resemblance to a black-and-white gumshoe movie ends, because the interior is covered in woodchip wallpaper that was either painted yellow or has just got stained that way over the years.

I plumped myself down on the threadbare settee in front of Harvey’s desk, retrieved the duffel bag he had let me leave there during our excursion, and watched as he flicked through all the keys once more to find the right one for the cash box he keeps in the top drawer.

I could have pointed out which one it was – I’ve got a good memory for things like that – but he’d only get shirty. The first job I did for him, he actually made me turn my back so I wouldn’t see where he got the cash box from. For a supposed detective he really doesn’t get how mysteries work. There’s only two desks in the room – his and his secretary’s – and I knew perfectly well which one he was standing behind.

‘One, two, three, four, five and five and ten is twenty.’ Harvey slapped the notes down on the table, then counted them through once again to make sure before handing them over. I stashed the one-pound notes in my jeans pocket, and tucked the bigger ones into my sock just in case I ran in to anyone unfriendly.

Harvey was laboriously writing an entry out in the ledger he keeps of all his transactions. He lives in terror of being arrested for living off immoral earnings, saying it would be the death of his old mum. I’m not sure why, because the ledger also features a regular outgoing for ‘ground rent’ which goes straight into the pocket of a local copper, Sergeant Mullaney, when he does his rounds of all the local business each week, on the understanding that he will ‘see them right’. In any case it doesn’t bother me. If the police or anyone else go looking for the name I sign under, they’re not going to find anyone.

Assistance with investigations: T. Wildeblood Esq. Harvey pushed the ledger across the desktop and proffered his fountain pen, not taking his eyes off it until it was safely back in his jacket pocket. ‘All right Tommy, piss off now, some of us have got homes to go to.’

I took my time getting up and shouldering my bag. ‘It’s Tom now,’ I told him. I had decided that if I was too old to go on the game, I didn’t need to go by a kid’s name any more either.

‘Is it indeed?’ He gave a yellow grin. ‘All right Tommy, whatever you say.’

I flicked a V-sign in his direction and set off down the noisy staircase.

THREE

First things first: get something in my belly. I hadn’t eaten all day, but with Harvey’s cash burning a hole in my pocket (and sock) I could afford a proper blow-out. I strolled round the corner and up Tottenham Court Road to the Dionysus, where I ignored the great glistening wad of cat meat revolving behind the counter and ordered the best hake and chips in London with plenty of salt and vinegar. Cod was off, as usual.

I made to take my meal over to one of the shiny tabletops, but the bloke came out from behind the counter waving his hairy arms around and yelling at me to get out: ‘I don’t want you lot hanging around in here – give the place a reputation.’ I tried telling him I wasn’t on the game any more but he was having none of it. ‘That’s what you all say, go on, bugger off,’ he told me as he shoved me out into the night. He pronounced bugger ‘bukka’. I wonder how long he’d been in England before he learned that phrase.

I walked back down the road instead, holding the newspaper-wrapped package inside my jacket like a hot-water-bottle until I reached the fountains outside Centre Point, risking piles by perching on their frigid concrete rim to unwrap it. Grease spots bloomed across weeks-old headlines about OPEC and the IRA. I can’t be doing with newspapers: the world around me is depressing enough without needing to know what’s going on in the rest of it. But when I spotted a nice big photo of John Curry posing with his gold medal I did scan the accompanying text as I ate. I wanted to see if they had addressed the obvious, but of course it was nowhere to be seen – this was a family paper, just look at page 3 if you don’t believe them.

Across the road a queue was growing outside the Astoria. According to the shonkily applied letters on the illuminated sign above the entrance it was showing Emmanuelle II: the line below was mostly giggling couples dotted with the odd dirty old man who hadn’t worked out he could see proper pornos if he cared to stroll just a couple of blocks further. At the foot of Tottenham Court Road the shopfronts were little more than lean-tos, the storeys above them jagged like a mouth full of pulled teeth, a great emptiness stretching back to the block behind. What German bombs had destroyed, three decades of British indifference had failed to put back. Behind me was the vast stabbing finger of Centre Point, every one of its floors in pitch blackness. It had been sitting empty for as long as I had been in London, and for years before that I’d been told. And tonight, like every night, there would be people, some of them boys I knew by name, bedding down in the underpass beneath it. If you’re looking for justice in this world, you’re definitely in the wrong part of London.

Still, at least tonight I wasn’t going to be one of them. I finished my dinner, licking my fingers and pressing them into the folds of the paper to make sure I got every last salty scrap, and was wondering whether I was going to have to spend another 30p on a pint in the Golden Lion or the Bricklayers just to keep warm when a Number 73 went past me with a familiar fat figure sitting on its top deck. Harvey, off to what he likes to pretend is his bachelor pad in Stoke Newington, though his mother in the basement would tell you a different story. I chucked the greasy ball of paper into the water behind me, hopped down from the wall and headed back towards Gerrard Street.

I’d been living in a squat in Camden until recently. It wasn’t a bad gaff, as long as you weren’t too attached to your personal belongings and could put up with the overwhelming smell of patchouli oil, but I’d got back a few evenings earlier and found my housemates had held a meeting in my absence – a committee, they called it – and my stuff was all bundled up in the hall and a long-haired couple were already doing a John and Yoko in my bed. Turned out my former pals had decided I was showing insufficient commitment to the United Secretariat of the Fourth International to remain a part of their collective. What that meant in practice was that someone had gone snooping in my room and discovered the piles of Red Weekly I was supposed to have been selling each week piled up under the mattress, which they’d helped to hoist up nicely out of the draught that came in under the door. My housemates worked out that I must have been paying my subs out of the cash I made from selling my body, and it doesn’t get more capitalist than that. To be honest it only gave them the excuse they’d been looking for: for all their talk of breaking down society’s structures, hippies are usually a bit funny around homos and there was one bloke on the top floor who made a big deal about going on Women’s Lib marches, but had never even been able to meet my eye.

So it was O.U.T spells out and out you go. I wasn’t over-bothered about leaving the squat, but I wasn’t about to go back to sleeping on the streets in the middle of winter either. I know you can usually pick up someone who’ll let you stay the night, but frankly I’d had enough of sleeping with men who make Arthur Mullard look like a catch and I really couldn’t be bothered with the hassle if I wasn’t getting paid for it. So instead I’d fallen back on a lucky lift from a few months before.

I reached the front door of Harvey’s building – the band upstairs were still clattering on – and crouched down as if I was tying my shoelaces. Instead I extracted a pair of shiny Yale keys from my sock, being careful not to dislodge the wad of notes that were also in there. I slid the first key into the lock, pushed the door and slipped into the dark and noisy hallway.

I’d nicked the keys out of Harvey’s secretary Alison’s desk when she’d made the mistake of leaving me alone in the office a few weeks ago. I hadn’t gone there intending to lift anything – I’d turned up for a job, after getting a message at the Bricklayers Arms that Harvey wanted to see me, only he was out for lunch and there was just her bashing away on her typewriter. The stuck-up cow had made it so clear she didn’t really trust me to stay in the office while she went out for her own lunch hour that I felt duty-bound to go through her desk drawers while she was gone. The spare keys were the only interesting thing in there – although I did take the chance to empty her dry shampoo out of the window to teach her a lesson – so I pocketed them, got copies made at the locksmiths on St Martin’s Lane, and then let myself back in to return the originals that very same evening, having a good look through Harvey’s paperwork while I was at it. That’s how I found out the girls were on a higher rate than me.

Anyway, the keys were coming in useful now, because for most of the week, and so far without either Harvey or Alison having the slightest suspicion, I had been kipping down on the settee in the office. I’d nearly bricked myself today when I got the message that Harvey wanted to see me, thinking I must have left something behind that had given the game away, so I was even more than usually pleased to find out he wanted me for a job.

I climbed the stairs, awareness of my intruder status making me take each tread as softly as possible, even though there was no chance of anyone hearing me over the din coming from the first floor. The key to the office door was just as good a fit, and I was soon safely inside. I had to leave the blinds open so the daylight would wake me well before Alison arrived to open up in the morning – it would be the end of everything if she found me still snoring away – but the last couple of nights I’d risked switching Harvey’s desk lamp on for my bedtime reading. I can’t get to sleep without reading. Well, or a wank, but I wasn’t going to risk that here.

I kicked off my plimsolls, shucked off my jeans and made myself as comfortable as I could on the lumpy cushions, draping my jacket over myself like a blanket. Rummaging in the bag that now contains all my worldly goods I extracted an orange-and-white paperback. It was an old favourite, pretty much the only thing I made sure to take with me when my dad threw me out, and the only thing I’ve managed to keep hold of ever since. This one I wouldn’t flog off for all the tea in China. It’s the book that saved my life.

The cover was pretty much hanging off it now, but I knew the text on it off by heart. A first-hand account of what it means to be a homosexual, and to be tried in a controversial case and imprisoned. And stamped beneath that: Property of Berkshire Public Libraries. That’s where I had come across it all those years ago. My parents didn’t read anything other than the Daily Express, and were bewildered by how keen I was on books. ‘He doesn’t get it from us,’ they used to tell their friends, just like later on they would be pointing out what else I hadn’t got from them. Anyway, they soon worked out that a library ticket would keep me quiet and out of their hair, and before too long I was spending every Saturday morning and most of the school holidays in our local branch. And that’s where I’d come across this. I was innocently browsing the non-fiction shelves, and found myself riven to the spot, petrified by the shock of seeing such a thing there in its ordinary Penguin cover just like all the others, standing in plain sight in such a respectable, official place, just a few streets away from my own family home.

I didn’t dare even take it down from the shelf, just jammed it straight back in between its innocent neighbours, convinced the whole library must be staring at me. Was I even allowed? The very title seemed to suggest I wasn’t: Against The Law. I had only just graduated from the buff pink of a junior ticket to the grown-up green, but surely even being officially an Adult Reader didn’t mean you were allowed to look at this sort of thing?

I remember I left without taking out a single book that day, too flustered to do anything but dump those I had already gathered on a trolley and flee. But after a sleepless night I came back the next morning, when I knew it would be quiet, and I snatched the incredible book down and took it over to the table at the furthest end of the reference library where no one ever sat, hid it inside an innocent-looking volume of the Children’s Britannica and read it from cover to cover for the first time that very day. I was 11.

I am no more proud of my condition than I would be of having a glass eye or a hare-lip. On the other hand, I am no more ashamed of it than I would be of being colour-blind or of writing with my left hand. It is essentially a personal problem, which only becomes a matter of public concern when the law makes it so.

It was June 1967, the start of the holidays. Out there, very much somewhere else and unbeknownst to any of us until long afterwards, something called the Summer of Love was going on. And in the stuffy airlessness of Latchmere Road Public Library and Reading Rooms, my own idea of love was changing forever.

The truth is that an adult man who has chosen a homosexual way of life has done so because he knows that no other course is open to him. It is easy to preach chastity when you are not obliged to practise it yourself, and it must be remembered that, to a homosexual, there is nothing intrinsically shameful or sinful in his condition.

There was nothing wrong with me. I couldn’t help how I felt.

The number of homosexuals in England and Wales has never been satisfactorily estimated. Some statisticians have given a figure of 150,000; others, of over a million. If the Kinsey Report, based on inquiries in America, is accepted as a rough indication, the figure for England and Wales can be estimated at 650,000.

There were other people like me out there. Lots of them. I wasn’t alone.

Looking back now I reckon one of them must have been working somewhere senior in that library. God knows who: the staff were all old women in twinsets the spit of Mrs Mary Whitehouse, and the doorkeeper still wore his war medals on his rather less impressive uniform. But who else could have smuggled this secret message of hope to boys like me in amongst the Willard Prices and Mills and Boons and Patience Strongs? At the time I was too caught up in my own feelings, too blown away by my new discovery, to think anything of the sort: instead I worried that the book itself was a trap, that at any second the full weight of the library authorities, the pursed-lipped shushing ladies and the ranked masses of headmasters and vicars and parents and police behind them would come crashing down on me and haul me away for public humiliation. After all, that was what happened to this extraordinary man, as I learned as I read on through the morning and into the afternoon, ears burning, heart thumping, too scared to continue but unable to stop. He had had his home raided and ransacked, his love letters broadcast to the world, his name plastered all over the newspapers, and he had been thrown in prison. And yet he had not backed down. He had stood up in front of the world and said ‘I am a homosexual’; he had put it down again in black and white in this book, published only a year after I had been born, so that everyone could understand it. And the more I thought about it – the more I read his words, over and over again, in the privacy of my bedroom, having liberated them from the library stuffed inside my shirt because the idea of standing at the issue desk face-to-face with another human being and having my name indelibly attached to them was just too terrifying – the more I felt I had a duty to do the same. I kept the book stashed between my mattress and the base of the bed where no one would find it, and each night I would read a few paragraphs like a catechism before sliding it under my pillow so that it would always be in comforting reach in the night. Somehow I always found the right words in there to reassure me, to comfort me, to point me in the right direction to go.

So that’s why I chose the name I go by. Tom Wildeblood. It’s not the name my mother and father would know me by. But then they don’t know me at all. They proved that just a few weeks later when Richard Baker shattered the peace of an evening at home by announcing that the government had voted to legalise ‘homosexual acts’ between consenting adults, and my father stood up and furiously slammed the TV off while my mother complained about feeling ‘physically sick’, and I sat there bright red and desperately trying not to cry. And I was more than happy to hammer the point home five angry, row-filled years later by packing my stuff and clearing off out of their lives forever.

The din from downstairs had ceased a while ago, and the familiar words of the book had lulled me to the point where I could almost forget quite how uncomfortable a bed the threadbare two-seater made. I yawned, and stretched, and was just reaching out for the switch on the anglepoise when I froze and was suddenly wide awake again.

Someone was coming up the stairs.

FOUR

Shit. Shit. Shit. Harvey must have come back. He must have forgotten something. I should have waited longer. Should have gone to the Golden Lion and stayed till closing time to make sure. Should have, would have, could have. But instead I was trapped here, frozen to the spot, flat on my back like a beetle, listening to the footsteps coming steadily up the stairs and my heart thumping loud in my ears, each beat of them bringing disaster closer and closer. There was nowhere for me to go. Nothing I could do. Even as I stared, transfixed, at the etched pane in the door a shape appeared and grew taller, bigger, sharper, closer, until it was directly outside the glass –

And then stopped, and knocked.

Why would Harvey knock before coming in to his own office? was the mad thought that flitted through my mind for a moment before it clicked. In a single fluid movement I leapt off the sofa and grabbed my trousers – no time to put them on – and got myself behind the safety of the desk.

‘Come in!’ I ordered, in a voice rather higher-pitched than I had intended.

The door swung open. The man standing hesitantly on the threshold was about ten years older than Harvey, and several stone lighter. He was dressed in high-waisted trousers and a blue blazer over a paisley shirt. He had thin, wispy hair with a bluish tint, and the saddest eyes I have ever seen.

‘I wasn’t sure you’d be open so late,’ he said apologetically. ‘I’ve been walking around for hours, wondering what to do, but then when I came past and saw your front door was open…’

‘No…no…no peace for the wicked,’ I stammered, cursing the band and trying desperately to remember if Harvey’s desk had an open front or not. I reached beneath the tabletop and tugged the tail of my shirt down as far as it would go. ‘What can we do for you?’

‘I…I… Oh dear.’ He plucked a white handkerchief from the breast pocket of his blazer and pressed it to his mouth, flapping a hand in the direction of the sofa in a gesture which dispelled any doubts I might have had that he was a queen. ‘I wonder – could I?’

I nodded, slightly over-eagerly. ‘By all means. Just shove all that stuff out of the way.’ He took his time, plucking my jacket up and folding it neatly, before he turned and sat down, perching on the very edge of the cushions, knees clamped together and twisted daintily to the left. Yanking my own arms up above the level of the desktop, I tried to compose my own top half into as authoritative a pose as possible.

‘Oh! It looks as if I’ve come to the right place.’

For a second I thought he had spotted my bare legs, but he was nodding at the book, which was still sitting on the edge of the desk where I’d left it. ‘Ah!’ I exclaimed. ‘Just…research.’

He nodded sadly. ‘I went down to Winchester for a day to see the trial. Such a dreadful injustice. Of course, it’s all different these days. For your generation.’

Oh yeah? I thought to myself, but I didn’t say anything. I wouldn’t turn twenty-one for another six months.

The visitor seemed to be considering the same subject. A look of doubt crossed his face. ‘I rather expected you’d be older,’ he ventured.

I gave him as reassuring a smile as I could manage. ‘I’m the junior partner,’ I bluffed. ‘Tommy Lewenstein. Tom.’

‘Ah.’ He looked reassured. ‘My name is Crichton. Malcolm Crichton.’ He rose from the sofa and offered me a hand, which, unable to get up, I had to stretch across the desk to shake. It was like gripping a handful of autumn leaves.

‘And what can we do for you, Mr Crichton?’ I seemed to have adopted the royal pronoun in my new role as the unsuspecting Harvey’s Boy Wonder. With a sinking feeling in my stomach I realised I was trapped in the part now. Whatever Crichton was after, I had to somehow ensure he went away happy and never darkened this doorstep again. I couldn’t even send him away and tell him to come back tomorrow, because the first thing he would say was ‘your son told me…’ and from there even Harvey’s detective skills were probably up to working out what had been going on.

Thankfully the old man seemed oblivious to the churning that was going on in both my belly and my mind. His eyes on the carpet, he was twisting the handkerchief around his fingers, lost in a torment of his own. When he finally spoke his voice was so soft I had to lean forward to hear him. ‘I had a friend. A young friend. He died.’

‘I’m sorry to hear that.’

‘I was very fond of him. I’d hoped… I’d hoped I might spend the rest of my life with him.’

‘Right.’ I folded my arms on the desktop and tried to look sympathetic. If all this bloke wanted was a shoulder to cry on, I could provide that, as long as he promised not to look down. I might even be able to get rid of him within half an hour.

Then he went and piqued my interest. ‘He was…he worked as a prostitute.’

‘Really?’

Crichton looked up with a sheepish smile, mistaking my tone. ‘I am not ashamed to admit that I pay for companionship on occasion, Mr Lewenstein. When one gets to my stage in life, one’s options are rather limited.’

‘No, no, of course, nothing wrong with that,’ I assured him.

‘But what Stephen and I had developed into something…rather special.’ He gave a wistful smile. ‘Latterly he would come and visit my home quite of his own accord. He said he enjoyed spending time with me.’

And I bet you never thought to count the spoons afterwards, I thought, but I kept it to myself. Punters like Crichton were every rent boy’s dream: I’d had a couple myself. A soft touch, we used to call them. Someone so besotted you could rely on them not just for regular payments but for bonuses too: gifts, meals out, even a roof over your head. All you had to do was keep telling them what they wanted to hear and you could get yourself looked after for life. I knew lads who had been bought cars, taken on holidays to Tangiers or Amsterdam: there was even talk of one guy who had been bought his own flat in Chelsea and given up the game forever, though no one you spoke to ever seemed to have actually met him. It was all pretty harmless unless the punter got jealous; then things could get nasty. Maybe that was what had happened to this Stephen. Crichton might well not have been the only sugar daddy he was stringing along.

I knew better than to suggest as much. The old man was obviously devastated, dabbing at his eyes with the unfurled handkerchief. ‘We’d even discussed me legally adopting him,’ he spluttered. ‘Stephen loved the idea. He had no family of his own, you see.’

Now I felt distinctly less sympathetic. I’ve not got much time for the normal nuclear family set-up, given my own experience of it, but what Crichton was suggesting sounded a lot less wholesome. ‘So what happened to him?’ I asked, a bit more harshly than I intended.

The old man looked up at me, his eyes brimming. ‘It was on Tuesday. I hadn’t seen him since the weekend – we’d had the most glorious time together. We came up to the West End and went round the shops. He was helping me choose things for the house, ready for him to move in. He was going to have his own room, decorated just as he liked. And then on the Monday morning he said he had to go, he wouldn’t say where, just that he had someone to see.’

Now I wondered if the mysterious Stephen had just staged his own disappearing act because Crichton was getting too clingy. I reached for the pad that Harvey keeps on his desk, realised too late that there was no pen to go with it, and had to bluff it out. ‘Do you have any idea who that person might have been?’ I asked. It sounded like the sort of thing detectives say.

The old man shook his head. ‘He never liked to discuss his work with me. I think he was worried about making me jealous.’ A soppy smile dislodged the tears and set them running down his cheeks. ‘Not that I would have been. I understood, he was a young man, we all have needs.’ He paused to blow his nose before continuing.

‘Monday was such a dismal day, if you remember. But Tuesday was rather a fine morning, although it was cold of course, and I decided to go out for a walk. I live near the Heath, you see. And I happened to pass near the Men’s pond.’

Sounds like Stephen was not the only one attending to his needs elsewhere, I thought uncharitably. There was no more notorious cruising ground than Hampstead Heath: no more guaranteed pick-up point than the area round the ‘clothing optional’ pond. But I quickly realised Crichton was avoiding my eye not from embarrassment, but from genuine anguish. ‘I could see a commotion from a distance. I’m not as fast on my feet as I used to be, but I hurried there as quick as I could, thinking I might be able to help in some way. I was an ambulance driver in the war, you see, and I thought perhaps my first aid…’ He tailed off and shook his head. ‘But it was far too late. I could see that even when they were pulling him out of the water. He was blue.’

He was rocking back and forth, all composure gone. Any hope of getting rid of him quickly was gone, but I no longer cared: I had been drawn in. ‘And it was Stephen?’ I prompted.

He nodded, not even bothering to attend to the tears that were running freely now. ‘I didn’t recognise him at first. Or perhaps I didn’t want to. But when they turned him over, and I saw his face…’

‘I’m sorry,’ I said helplessly.

‘He was covered in bruises. His poor eye was all puffed up. The policemen tried to say it was just the effect of the water, but it was obvious. They kept saying he must just have gone for a swim and drowned. They were saying it as soon as they arrived, before they’d even looked at him, at his… body. It was as if they had already made up their minds.’

‘But you don’t believe that?’

He looked at me incredulously. ‘In February?’