Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Atlantic Books

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

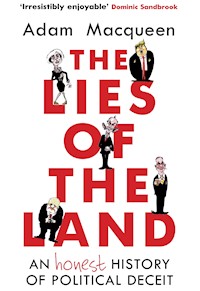

Trust in our politicians is at an all-time low. We're in a "post-truth" era, where feelings trump facts, and where brazen rhetoric beats honesty. But do politicians lie more than they used to? And do we even want them to tell the truth? In a history full of wit and political acumen, Private Eye journalist Adam Macqueen dissects the gripping stories of the biggest political lies of the last half century, from the Profumo affair to Blair's WMDs to Boris Johnson's £350 million for the NHS. Covering lesser known whoppers, infamous lies from foreign shores ("I did not have sexual relations with that woman"), and some of the resolute untruths from Donald Trump's explosive presidential campaign, this is the quintessential guide to dishonesty from our leaders - and the often pernicious relationship between parliament and the media. But this book is also so much more. It explains how in the space of a lifetime we have gone from the implicit assumption that our rulers have our best interests at heart, to assuming the worst even when - in the majority of cases - politicians are actually doing their best.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 535

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2017

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Praise for The Lies of the Land

‘Sure to find an eager audience... Like a sort of giant supermarket sweep through the dodgier aisles of Westminster, in which the author dashes round collecting up all the best reasons never to trust the establishment again, it’s lively entertainment’

Observer

‘The perfect bedside book’

Guardian

‘Fun [and] digestible... There is something staggering about the sheer weight of untruthfulness that oozes from the pages’

Prospect

Also by Adam Macqueen

The Prime Minister’s Ironing Board and Other State Secrets

Private Eye: The First 50 Years, an A–Z

The King of Sunlight: How William Lever Cleaned Up the World

First published in hardback in Great Britain in 2017 by Atlantic Books, an imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd.

This updated edition published in 2018

Copyright © Adam Macqueen, 2017, 2018

The moral right of Adam Macqueen to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Paperback ISBN: 978 1 78649 251 7

E-book ISBN: 978 1 78649 250 0

Printed in Great Britain

Atlantic Books

An imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd Ormond House

26–27 Boswell Street

London

WC1N 3JZ

www.atlantic-books.co.uk

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

1. OUT OF DEFERENCE

2. SEX LIES

3. FINANCIAL FIBBING

4. GAMBLERS’ CONCEITS

5. SINS OF SPIN

6. CONTINENTAL DRIFT

7. WHERE POWER LIES

8. BREAKING THEIR WORD

9. WHOSE TRUTH IS IT ANYWAY?

CONCLUSION

EPILOGUE: DON’T STOP (NOT) BELIEVING

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

NOTES

INDEX

For my brother Andrewwho likes ‘books which are true’and isn’t keen on politicians who lie.

‘An old gentleman had been serving on a battleship as a young rating in early 1940 when Churchill had come aboard. Put in a group to question the great man, he had nervously asked, “Is everything you tell us true?” The answer, he alleged, was: “Young man, I have told many lies for my country, and I will tell many more.”’

Anecdote recounted by formerCabinet Minister William Waldegravein his memoirs, 2015

‘Truth is a difficult concept.’

Ian McDonald, official at the Ministry of Defence, in evidence to the Scott Inquiry, 1993

‘I only know what I believe.’

Prime Minister Tony Blair on his approach to events after 9/11 and the Iraq War, speech, 2004

‘You are fake news!’

President-elect Donald Trumprefuses to answer a question from CNN, press conference, 2017

INTRODUCTION

How do you know when a politician is lying? runs the age-old joke. Answer: Their lips are moving. Always gets a big laugh in the saloon bar, that one. Bet Nigel Farage has trotted it out more than once.

Like most jokes, it’s 90 per cent nonsense wrapped around a hard kernel of truth.

There are plenty of elected representatives out there living perfectly upright lives. They do their best for their constituents, balance their beliefs with the demands of office and professionalism, speak truth to power and attempt to wield what power comes their way in a manner that brings the greatest benefit – or at least does the least damage – all round.

So why are we convinced otherwise? Why, as the Brexit referendum and an embarrassment of elections in recent years have repeatedly demonstrated, have we become so determined to think the very worst of those who aspire to serve us?

Some of it is down to the extraordinary polarization of contemporary politics. Many voters have evacuated the centre ground for entrenched positions held independently of the traditional redoubts of the party system. If you bolster your own righteousness by dismissing the other side as inherently evil and beyond salvation, what can their every utterance be but a lie? Trump’s army of ‘deplorables’ call it ‘fake news’. Hard-core Brexiteers rail against ‘project fear’. The cult of Corbyn dismiss the ‘smears of the mainstream media’. And the laser-focused EU negotiation team offered to the nation by Theresa May in the summer of 2016 appeared to deem any and all alternative points of view as something not far short of treason.

As sure as night follows day, the louder you shout about your opponents’ lies, the less obliged you feel to tell the truth yourself. The book is far from closed on the presidential team’s links to Russia. There is not, and there was never going to be, £350 million a week to solve the problems of the NHS. Leaders are capable of looking incompetent all by themselves. And the prime minister could boast of as big a parliamentary majority as she likes, but it’s not even a minority interest of Guy Verhofstadt, Michel Barnier, Donald Tusk or anyone else beyond our borders.

But while downright dishonesty may have increased in volume and visibility in recent years, it is not a new development in politics. For decades now we have felt that our elected representatives speak with forked tongues. There is a very good reason for that. It is the other 10 per cent of the joke. It is the fact that they do.

Of course they don’t lie all the time. That’s only true in a few cases, those of pathological liars programmed to believe whatever happens to be coming out of their mouth at any given moment. We’ll see some examples in the stories of Jeffrey Archer and Donald Trump, both of whom have built a well-deserved reputation for their lying. We’ll also see it in the tales of Mohamed Fayed, who though he is not a politician himself has nevertheless been the facilitator and funder of more than one incident of spectacular lying which appears in these pages.

But then, very few people out there are listening all the time either. Beyond the wonks of Westminster, the loyal partisans and the dedicated readers and viewers of political journalism (who for the most part – let’s be honest – tend to be other political journalists), most of politics coalesces into a shapeless ball of noise. The bulk of the population perceive only something we might call ‘Politicians with a capital P’ (followed by a sigh). Politicians with a capital P are a not trustworthy but nevertheless authoritative mass, always there on the nightly news and in the papers and the Facebook feed, getting in the way of the sport and showbiz gossip and your friends’ family pictures. Very occasionally a clear statement, pledge or personality breaks out of the background noise. In spin-doctoring circles, these are known as the moments with ‘cut-through’.1 All too often, these moments are not exactly the ones the spin doctors want us to be focusing on.

As one prime example, how often these days do you hear people bring up the topic of how tirelessly Tony Blair worked first to corral George W. Bush and then to get the UN Security Council to pass Resolution 1441 condemning Saddam Hussein’s ‘non-compliance’ to ensure the US didn’t go into Iraq without some international backing?2 Probably not much. But it is an unbreakable rule of these first decades of the twenty-first century that any conversation about British politics, on almost any topic, on- or offline, will at some point default to the claim that the former prime minister lied about WMDs in order to take us into an illegal war. I happen not to believe that is true – don’t worry, I’ll explain why in chapter 7 and you’ll have every opportunity to denounce me as a Blairite lickspittle neocon. But as we have already seen, one of the curious things about the loudest accusations of lying is that those making them don’t feel obliged to tell the whole truth.

It’s always the bad behaviour that sticks. Can you name one achievement of the Nixon administration other than Watergate? Do you have any idea what government positions John Profumo held before he had to resign from them in disgrace? Which action taken in the Oval Office by Bill Clinton is the first to spring to mind? And those are just the classics. Within these pages you will find many less well-known incidents of chicanery, double-dealing, alternative facts and outright falsehoods. En masse, they form the folk memory that has ushered us into the much-vaunted ‘post-truth’ era. They are the reason so many of us feel unable to believe anything a politician says.

The bigger question is why politicians lie, dissemble, mislead or simply go to great efforts to avoid telling us the truth in the first place.

Discipline obliges dishonesty. During the 2017 general election campaign every Tory, from Theresa May downwards, was programmed to avoid saying anything at all except the phrases ‘strong and stable’ and ‘Coalition of chaos under Jeremy Corbyn’. Both soundbites looked risibly ironic when polling day left May as the weakest and wobbliest prime minister in recent history, only able to limp back into power by bribing the DUP to stand alongside her. But parroting the party line and offering no hostages to fortune has always been a principle for the foot soldiers of politics, rigidly enforced by their sergeant majors, who hold both the carrot of career advancement and the stick of a media mauling.

It is that same fear – imposed both by party whips and by a lobby press with a shameless, symbiotic relationship with the hierarchies it ought to be holding to account – that ensures politicians who are under-informed, unprepared or unable to think on their feet (a bit like most of us, most of the time) are reduced to bullshitting their way through everything. Their unstudied interviews, once broadcast or printed, acquire an authoritative status that might as well be carved in tablets of stone. Entire policies and political crises have been constructed around the inability of a powerful person to admit, in the moment, ‘I don’t know.’

There is also the sheer overweening arrogance that overtakes the elected once they reach a certain point in their careers. Being driven everywhere, having an army of civil servants to attend to your every need, flying in and out of receptions and banquets where everyone wants to talk to you and toast your eminence is not a good diet for the ego. It is especially bad for those whose egos were big to start with. A calling can all too easily turn into a mission; a mission in time can mutate into a conviction that you, and only you, have the answers that will save the world. It is a quality that singles out our best prime ministers – Winston Churchill, Margaret Thatcher, Tony Blair – and also simultaneously makes them our worst. Self-belief can convince you that everyone else should believe you too. Then things like empirical truth are for the little people.

And marching behind the righteous are the reckless, those whose own personality flaws manifest in an extraordinary desire to play with fire – be it sexual affairs, financial fiddles, or the sheer thrill of risk itself. From Jeremy Thorpe to Jonathan Aitken, they did not so much sow as scatter the seeds of their own destruction.

Some of them were simply greedy, unhappy to settle for the spiritual rewards of public service when the potential pecuniary ones remain much more generous. Yet, however those of us who pay their wages might feel about it, the rules say that being an MP is not a full-time job. It is perfectly possible for a politician to be straightforward and honest about exploiting opportunities for enrichment. The ones who have lied about it did so for a different reason. MPs like Aitken and Neil Hamilton are often described as shameless. The opposite was the case. It was shame that made them deny their sins so loudly for so long, just as it was a collective, institutional shame that prompted Parliament to resist perfectly reasonable enquiries about its expenses system, until finally, in 2009, the curtain was whipped back to expose our ruling class in all its naked, squirming venality.

From Nixon onwards, it has always been the cover-up that does for them. A fear of how transactions might be perceived has led both Tory and Labour leaders to try to keep the whole ‘murky business’ of political donations and honours (the description is Tony Blair’s) out of sight and out of public mind.3 A vicious cycle – public mistrust leading to private dissembling leading to greater public mistrust – has been established. They tell us lies because they know they can’t expect us to believe them.

The result is that the one profession in whom we are regularly required to register our trust at the polls, is the one the polls show we least trust. At the end of 2016 just 15 per cent of the British public said they trust any politicians to tell the truth; the next least trusted profession, with 20 per cent, was ‘government ministers’. You can take my word for this, even though, as a journalist, I’m right there in third place with 24 per cent credibility.4

With trust all round at such a dismal low, we enter the realms of farce. In April 2016, Secretary of State for Culture, Media and Sport John Whittingdale faced some embarrassment. It was revealed – perhaps belatedly, since he was in charge of implementing press regulation after the Leveson inquiry, and this may have made the papers less keen on exposing his peccadillos – that the minister had been going out with one Olivia King, a dominatrix who worked under the professional name ‘Mistress Kate’. ‘Between August 2013 and February 2014, I had a relationship with someone who I first met through Match.com,’ Whittingdale admitted. ‘She was a similar age and lived close to me. At no time did she give me any indication of her real occupation and I only discovered this when I was made aware that someone was trying to sell a story about me to tabloid newspapers. As soon as I discovered, I ended the relationship.’5

It turned out that Mistress Kate was not the only one who had fibbed about their occupation, however. Another woman, called

Stephanie Hudson, came forward to say she too had gone out with the veteran politician after meeting him on the same website. But she said Whittingdale – who had worked as political secretary to Margaret Thatcher, been an MP since 1992 and headed the influential select committee on culture before ascending to the cabinet – had not revealed what he actually did for a living.

He told her he was an arms dealer instead.6

How the hell did we get here?

1

OUT OF DEFERENCE

There is a famous political interview from the General Election of 1951 in which the BBC’s Leslie Mitchell promises to ‘cross-question’ senior Conservative Sir Anthony Eden. ‘I would like to feel that I am asking, so far as possible, those questions which you yourselves would like to ask in my place,’ he told viewers. Then he goes in with a real zinger: ‘Well now, Mr Eden, with your very considerable experience of foreign affairs, it’s quite obvious that I should start by asking you something about the international situation today, or perhaps you would prefer to talk about home. Which is it to be?’1

Paxman he was not. It would be a further four years before Robin Day on the new ITV jump-started the sort of adversarial political interview to which we have become accustomed. Day-to-day political reporting consisted mostly of producing page after page of transcripts of parliamentary speeches, taken down at shorthand speed and reproduced verbatim, thus allowing MPs – and their unelected counterparts in the hereditary House of Lords – to effectively write their own accounts of their activities.

None of this seemed remarkable at the time. Hierarchies, and the deference that was due to them, were embedded and enforced in every institution: the arcane pecking order of the public schools was echoed in the state sector by the eleven-plus division, which defined the course of a pupil’s life. And whether they then found themselves on a factory floor or in a professional body, they were locked into a rigid system of willing conformity. National service, which lingered as a hangover of the war right up until 1960, trained every man to unquestioningly accept the authority of his elders and betters, while women were expected to know their place, which, once married, was in the home.

Through everything ran the vast system of self-regulation that is class in Britain. As if stamping down on the brief socialist aberration of Attlee’s government, when Winston Churchill was re-elected in 1951, he appointed two marquesses, four earls, four viscounts and three barons as ministers. The commoners in the cabinet seemed to work on the hereditary principle too. Anthony Eden married Churchill’s niece Clarissa in 1952 before following her uncle into Number 10, and Duncan Sandys, another of his cabinet colleagues, married Churchill’s daughter Diana.

In such an atmosphere, is it any wonder that honesty and openness to one’s social inferiors was not a priority for politicians? But voters did demand that their rulers be accountable for their actions. And that was a lesson Britain’s political elite were about to learn the hard way.

* * * * *

‘For a long time the Prime Minister has had no respite from his arduous duties and is in need of a complete rest. We have therefore advised him to abandon his journey to Bermuda and to take at least a month’s rest.’

Lord Moran and Sir Russell Brain,doctors to Sir Winston Churchill, press bulletin, 27 June 1953

The prime minister was on fine form that night. He had been knocking back the booze in his customary manner, and when he rose to say a few words in honour of his Italian counterpart, Alcide De Gasperi, the guests in Downing Street agreed it was a classic of its kind. ‘He made a speech in his best and most sparkling manner, mainly about the Roman Conquest of Britain,’ noted his principal private secretary Jock Colville, who not so long before had been worrying that the increasing amount of speechwriting he had been asked to do was ‘a sign of advancing senility’ in his seventy-eight-year-old boss.2 The mood in the room was boisterous and joyful as the meal concluded and Churchill stood up again to urge his guests through from Number 10’s dining room to the drawing room. But he only made it a few steps before he staggered and sat down heavily on a recently vacated chair. Elizabeth Clark happened to be beside him at that moment, and he clutched her hand. ‘I want a friend,’ he muttered, not quite focusing on her face. ‘They put too much on me. Foreign affairs…’ Then he tailed off into silence.3

She kept it together. Although she couldn’t spot Churchill’s wife, Clementine, in the melee, his daughter Mary was still in her seat at the opposite end of the long table, and Elizabeth dispatched her husband – the eminent art historian Sir Kenneth – to quietly attract her attention. Mary sent her own husband, Christopher Soames, to retrieve his mother-in-law from the crowd next door. Not wanting to cause a diplomatic incident in front of the Italian prime minister, he told her, slightly pointedly, that Winston was ‘very tired’. Perhaps thinking her husband had had too much to drink, Clementine nodded and said, ‘we must get him to bed then.’ She soon realized it was something more serious when Soames whispered: ‘we must get the waiters away first. He can’t walk.’4

He couldn’t walk properly the next morning either, when his personal physician, Lord Moran, came to his bedroom for a check-up. Wanting a second opinion – his own – Churchill insisted that the doctor open the door of his wardrobe so he could see his own unsteady efforts in its mirror. ‘What has happened, Charles?’ he asked sadly. ‘Is it a stroke?’5

It was. And Moran told him that walking might be the least of his problems: ‘I could not guarantee that he would not get up in the House and use the wrong word; he might rise in his place and no words might come.’ The doctor might also have been tempted to say ‘I told you so’: just one day previously he had warned Churchill that he was ‘unhappy about the strain’ upon him, that ‘it was an impossible existence.’6 As well as his own duties, the prime minister had insisted on shouldering those of the foreign secretary too: Anthony Eden was off sick after an operation to remove gallstones went disastrously wrong. Churchill, whose main medical complaint was a deafness that became particularly acute when colleagues mentioned the word ‘retirement’, was rather chuffed about this fact: Eden was twenty-three years his junior and his chosen successor, although his boss was determined to make him wait for his promotion as long as possible.

Thankfully the cabinet were an unobservant lot, because none of them noticed the state the prime minister was in when he insisted on chairing a meeting that morning. Despite the fact he was slurring his speech and unable to move his left arm, the chancellor only noticed that he was ‘very white’ and didn’t speak much.7

By lunchtime Churchill had difficulty getting out of his chair. The following morning Moran found him, ‘if anything, more unsteady in his gait’ and ‘becoming more blurred and difficult to follow’ when he talked. But Moran’s main concern does not seem to have been medical: ‘I did not want him to go among people until he was better. They would notice things, and there would be talk.’8

So a plan was hatched – or rather a plot hardened around Soames’s first instinct for discretion over resuscitation. The prime minister’s illness must be covered up at all costs. That afternoon he was driven down to his private residence, Chartwell, in Kent, accompanied by Clementine and Colville, who noticed sadly that his boss was now having difficulty finding his mouth with his trademark cigar. By that evening the paralysis had spread over most of Churchill’s left side; by the next day, he could barely move. Moran gave his professional opinion that he didn’t expect the PM to live through the weekend. But they had their orders, slurred to them by Churchill himself: they were under no circumstances to let it be known that he was incapable of running the country. Government was to continue as if he were in full control.

Certain people did have to be told. Colville telephoned the Queen’s private secretary to pass on a message that the monarch – herself in the job for just eighteen months at this point – might find herself having to appoint a new prime minister at very short notice. The US president had to be told too. Churchill was due to hold a summit in Bermuda with Eisenhower on 9 July, the first face-to-face manifestation of the ‘special relationship’ since the death of its wartime third wheel, Joseph Stalin, in March. In January Churchill had travelled by boat to meet the newly elected president after Moran warned him that air travel posed a danger to his circulation; now that the risk had become a reality, there could be no question of him going at all. ‘You will see from the attached medical report the reasons why I cannot come to Bermuda,’ the prime minister – or rather Colville on his behalf – telegrammed the White House.9 The US administration could at least be trusted to keep the secret. After all, they had helped disguise the extent of Franklin D. Roosevelt’s paralysis, brought on by polio, from voters for years.

But it certainly wasn’t the sort of thing the whole government needed to be told about. Instead, only two men were told. Chancellor Rab Butler and Lord President of the Council Lord Salisbury were summoned to Chartwell that Saturday, where Colville solemnly handed them a formal letter:

I write, very sorrowfully, to let you know quite privately that the PM is seriously ill and that unless some miracle occurs in the next 24 hours there can be… little [question] of him remaining in office. It was a sudden arterial spasm, or perhaps a clot in the artery, and he has been left with great difficulty of articulation although his brain is still absolutely clear. His left side is partly paralysed and he has lost the use of his left arm. He himself has little hope of recovery.10

With Buckingham Palace at the other end of the telephone line, the trio neatly sorted things out. If Churchill died, or had to resign, then Salisbury – who owed his place in Parliament to the favours his ancestors had performed for James I and George III – would take over running the country; not as prime minister – everyone agreed Eden was the best fellow for that job – but as ‘chairman’ of a caretaker government that might hold the fort until the foreign secretary had made a full recovery and himself moved into Number 10. There was no question of involving the electorate – or even the Conservative Party – in the matter. That was not how things were done.

The two cabinet ministers cast an eye over the bulletin that Moran and a specialist neurological surgeon, the aptly named Sir Russell Brain, proposed to issue to the press. ‘For a long time the Prime Minister has had no respite from his arduous duties,’ it read. ‘A disturbance of the cerebral circulation has developed, resulting in attacks of giddiness. We have therefore advised him to abandon his journey to Bermuda and to take at least a month’s rest.’11 The statesmen agreed that this would not do at all: great war heroes didn’t get giddy, and the medical terminology might make people think Churchill was at death’s door. He was, of course, but there was no need to say so. The middle sentence was excised completely and replaced with the bland phrase ‘and is in need of a complete rest’. Moran himself was dubious – he wrote in his diary, ‘if he dies in the next few days will Lord Salisbury think his change in the bulletin was wise?’ – but he was just a doctor, and was easily overruled.12

Now all they needed to do was ensure that no journalists asked any awkward questions. Thankfully, that was a simple task: Colville had already gone over their heads. Twenty-four hours before Butler and Salisbury arrived at Chartwell, Colville had hosted the men with the real power in the country: Lord Camrose, owner of the Daily Telegraph, Lord Beaverbrook, who owned the Daily Express and Evening Standard, and Lord Bracken, who chaired the company which owned the Financial Times. All three were ‘particular friends’ of Churchill. Camrose had bought the very house they were meeting in and presented it to the prime minister when he found himself suffering from financial embarrassment, and Bracken and Beaverbrook had been co-opted into the cabinet during the war. As well as pledging to keep all news of the seriousness of the prime minister’s illness out of their papers, they also promised to persuade their fellow proprietors to do the same. And they were as good as their word. ‘His trouble is simply tiredness from over-work’, the Sunday People assured its readers on 28 June.13 ‘They achieved the all but incredible, and in peace-time possibly unique, success of gagging Fleet Street, something they would have done for nobody but Churchill,’ wrote Colville many years later, after the truth had come out.14

When Tony Blair suffered a considerably less serious health scare exactly fifty years later, his official spokesman was briefing journalists on how to spell ‘supra ventricular tachycardia’ the next day. But in 1953 the country was just eight short years on from the days of loose lips sinking ships and keeping calm and carrying on. When it came to the wartime leader, journalists were content to slip back into discreet and deferential mode.

At that point everyone imagined they were involved in a very short-lived deception. No one expected the prime minister to make it through the weekend. But much to everyone’s surprise, he did. ‘By Monday morning, the Prime Minister, instead of being dead, was feeling very much better,’ wrote Colville years later. ‘He told me that he thought probably that this must mean his retirement, but that he would see how he went on.’15 He certainly had no intention of going anywhere before the Conservative Party Conference that October. And so there was no choice but to continue the prevarication.

The cabinet were informed in the afternoon that the prime minister’s condition was more serious than originally thought, but the revelation was carefully not minuted. ‘It was a terrible shock to us all,’ wrote future prime minister Harold Macmillan. ‘Many of us were in tears or found it difficult to restrain them.’16 But they were also informed that despite his debility, Churchill remained very much in charge. Red boxes full of official papers continued to be sent down to Chartwell over the next month, and then to the PM’s official country residence, Chequers, for three weeks after that, as Churchill recuperated. He never saw much of their contents. Instead Colville – a civil servant – and Soames, a mere backbench MP, dealt with the prime ministerial paperwork. ‘The 33-year-old Soames… quite unobtrusively, took a hundred decisions in Churchill’s name without once breaching the trust which such a heavy responsibility involved,’ writes the PM’s admiring biographer Martin Gilbert.17 ‘There is some ambiguity about whether Colville and Soames faked his initials on papers,’ notes Gilbert’s more sceptical counterpart Roy Jenkins.18

Churchill did not return to Downing Street until 18 August, the day after the Daily Mirror – implacably opposed to the Tory prime minister – finally broke ranks and demanded to know: ‘WHAT IS THE TRUTH ABOUT CHURCHILL’S ILLNESS?’ The impudent query had been prompted after an American newspaper dared to use the word ‘stroke’ in a report on rumours about the PM’s health. Why, the Mirror demanded, should the British ‘always be the last to learn what is going on in their country? Must they always be driven to pick up their information at second hand from tittle-tattle abroad?’19

Apparently so. For while Churchill raged that the Mirror’s report was ‘rubbish, of course’, he had already ensured that the White House was fully acquainted with facts that would not emerge on his own side of the Atlantic for years to come. ‘I had a sudden stroke which as it developed completely paralysed my left side and affected my speech,’ he had written to Eisenhower way back on 1 July. ‘Four years ago, in 1949, I had another similar attack and was for a good many days unable to sign my name. As I was out of office I kept this secret’.20

‘His case has been the subject of close investigation. No evidence has been found to show that he was responsible for warning Burgess or Maclean. While in Government service he carried out his duties ably and conscientiously. I have no reason to conclude that Mr. Philby has at any time betrayed the interests of his country, or to identify him with the so-called “third man”, if, indeed, there was one.’

Harold Macmillan,House of Commons, 7 November 1955

Russian spy Donald Maclean had more than one lucky escape. Both the British and American secret services knew from a series of intercepted and decoded messages that the Soviets had an agent going by the code name ‘Homer’ working in the British embassy in Washington in the late forties. Maclean, who had been recruited to the Foreign Office straight out of Cambridge, was first secretary there. But it was taken as read that no high-ranking diplomat would betray his country. Only the lower classes did that sort of thing. Far better to look into the typists and clerks, the janitors and chauffeurs. One of them had to be Homer.

Even when Maclean underwent a spectacular breakdown after being relocated to Cairo in 1948, no one thought any the worse of him. All right, so he went on day-long drinking benders where he ranted about the awfulness of Americans, attacked his wife in public and broke into a stranger’s flat and trashed it…. Nothing that a recall to London and a spell under the care of a top Harley Street psychiatrist couldn’t sort out.

In early 1951, however, the evidence became undeniable when a US cryptographer managed to decode a Russian message dating back to 1944. It revealed that Homer’s wife was pregnant at the time and had gone to stay with her mother in New York. Only one man fitted the bill: Maclean, now working on the American desk at the Foreign Office in London. The CIA relayed the information to their British counterparts, with whom they enjoyed a good relationship – a relationship overseen at the Washington end by top MI6 man Harold Philby, known to his many friends as Kim.

The news came as a particular blow to Philby, because Maclean was an old friend; although they hadn’t seen each other in years, they had been students together in the early thirties. Philby was so shaken by the revelation of his pal’s treachery that he had to share the news with another mutual friend from Cambridge who, as it happened, was living in the basement of his home having recently completed a stint at the British embassy. The friend’s name was Guy Burgess. Neither man could bear to think of Maclean back in Britain, his home and office bugged, and officers from MI5, who dealt with enemy agents, following him everywhere to gather evidence for when he inevitably went on trial for treachery.

It wasn’t the only bad news Burgess had received in recent days. He had just lost his job, after a litany of bad behaviour and drunkenness culminated in him being caught speeding three times in a single day and rowing with the traffic cops when he tried to claim diplomatic immunity. The night before he went back to London in disgrace, he and Philby dined together at a Chinese restaurant, rather a tacky place where the piped music was so loud it was impossible to hear what other people were saying. Afterwards Philby drove him to the station and dropped him off with a somewhat unusual farewell: ‘Don’t you go too!’21

But Burgess did. On the night of Friday 25 May 1951, the very day the foreign secretary gave formal approval for MI5 to bring Maclean in for interrogation, Burgess turned up at Maclean’s home in Kent with a rented car. Astonishingly, the surveillance on Maclean was a nine-to-five job: his MI5 tail saw him from his office and onto his train at Victoria station, and then knocked off for the night. Thus no one saw the two men driving off into the darkness, headed for Southampton and a cruise ship sailing for France at midnight. The luggage that Burgess had carefully packed made the return trip to Britain, but he and Maclean did not. Instead, they took various trains to Switzerland where, with the help of false passports they picked up at the Russian embassy, they boarded a plane for Prague, where the Iron Curtain closed behind them. The first clue anyone at MI5 had about it was when Maclean failed to get off his commuter train on Monday morning. They had been planning to seize him that morning: his first interrogation was scheduled for 11 a.m.

Both Burgess and Maclean had been spying for the Russians since 1935. Recently, however, their controller, Yuri Modin, had concluded that they were both ‘burnt-out’.22 Even before Maclean’s cover was blown, both men had been making a spectacle of themselves with their drunken antics. Burgess was particularly unsuited to being a spy: permanently sozzled, he drew attention to himself everywhere he went; when he wasn’t picking fights, he was seducing anything in trousers. Since neither man could be trusted to keep shtum under questioning – quite the opposite, in fact – Modin felt he had no choice but to pull them out. But if their disappearance was bad news for Britain, it was terrible news for Kim Philby, who knew suspicion would inevitably fall on their old friend. He expressed his horror in a phone call to an MI5 contact, Guy Lidell, who dutifully reported back to his superiors: ‘There is no doubt that Kim Philby is thoroughly disgusted with Burgess’s behaviour.’23 Privately, Philby reassured himself that ‘there must be many people in high positions… who would wish very much to see my innocence established. They would be inclined to give me the benefit of any doubt’.24

And they were. Philby was recalled to London to discuss his friends’ exploits, but he was given the news in a friendly note from his boss ahead of the official telegram. The same boss accompanied him to his MI5 interview, where he was offered tea and allowed to smoke his pipe. A couple of days later they had him back for a slightly more frosty chat: the CIA were kicking up a fuss and saying they didn’t want him back in Washington. He had been helped by his long-running friendship with one of the top men in the CIA, James Jesus Angleton, who had assured his superiors that there was no way Philby could possibly have known about Burgess’s treachery. Yet the Americans were still insisting that the British ‘clean house regardless of whom may be hurt’.25 As for his MI6 colleagues, they were standing 100 per cent behind him. ‘Philby had not run away, he was happy to help, and he was, importantly, a gentleman, a clubman and a high-flier, which meant he must be innocent,’ writes Ben Macintyre in A Spy Among Friends, his superb account of Philby’s career. ‘Many of Philby’s colleagues in MI6 would cling to that presumption of innocence as an article of faith. To accept otherwise would be to admit that they had all been fooled; it would make the intelligence and diplomatic services look entirely idiotic.’26

So instead they chose to blind themselves to the truth. Philby had volunteered to spy for the Russians long before he ‘dropped a few hints here and there’ and bagged himself a berth at MI6 in 1940. The background checks done at the time of his recruitment turned up the result ‘nothing recorded against’: a chat with his father, an adviser to the king of Saudi Arabia, had been enough to convince recruiters that his flirtations with communism at Cambridge in the thirties were ‘all schoolboy nonsense. He’s a reformed character now.’ Besides, no less a figure than MI6’s deputy head, Valentine Vivian, had provided a reference of the most unquestionable kind: ‘I was asked about him, and I said I knew his people.’27

Philby in turn had passed Burgess and Maclean’s details on to the NKVD, precursor to the KGB. And it was he who had tipped off his Soviet contact in the US that Maclean’s cover had been blown, and he who arranged for Burgess to get Maclean to the extraction point. When Philby realized Burgess, to whom he was directly and obviously connected, had gone too, he had considered fleeing himself. In the end, he had decided to stay put and bluff.

He had come close to discovery before and got away with it. In 1937, when he was still filing reports on the Spanish Civil War for The Times as well as more secret ones for Moscow, a defector had described a ‘young Englishman, a journalist of a good family’ who was out in Spain, but no one made the connection. In 1945 Konstantin Volkov, the deputy chief of Soviet intelligence in Turkey, announced to staff at the British embassy that he wanted to come across too, and offered a list of Russian agents in Britain which he said included ‘one fulfilling the functions of head of a section of the British counter-espionage service in London’, a description which Philby swiftly recognized as himself. That time, he had been in a position to do something about it: the report about Volkov landed on his own desk at Section IX, which was dedicated to the ‘professional handling of any cases coming to our notice involving communists or people concerned in Soviet espionage’. He arranged to go to Istanbul himself to extract Volkov and his wife. Naturally, he made sure that the Russians got there first, and the couple were spirited away to Moscow where they were tortured and killed. A ‘ “nasty piece of work” who “deserved what he got” ’ was Philby’s considered, and psychopathic, opinion.28

His dual lives continued along weirdly parallel lines: in 1946 he was awarded both the OBE and the Soviet Order of the Red Banner in recognition of his work for the country’s respective secret services. By then he was even being talked about as a future head of MI6, not least by his biggest fan, Sir Stewart Menzies, who currently held the role of ‘C’. As a stepping stone on the way he was sent to Washington to serve as MI6’s ‘linkman’ with the newly created CIA. This gave him complete access to the secret communications between Britain and America. Immediately, a great many bilateral operations started to go wrong: agents working in Ukraine, Lithuania, Estonia and Armenia disappeared in mysterious circumstances, while CIA-funded insurgents in Albania were picked up by secret police who seemed to already know the details of their plans. It is estimated that Philby’s actions directly resulted in the deaths of up to two hundred guerrillas in Albania, plus thousands of their relatives and associates. He just shrugged. ‘They knew the risks they were running. I was serving the interests of the Soviet Union and those interests required that these men were defeated. To the extent that I helped defeat them, even if it caused their deaths, I have no regrets.’29

This was the man MI6 closed ranks to protect. But they couldn’t keep him on, they sadly concluded. His association with Burgess was just too close, and, now that MI5 had actually bothered to look properly, they had discovered all sorts of other dubious things about him – such as the fact he had not only moved to Vienna in 1933 to hang out with revolutionaries, but actually married one of them, Litzi Kohlmann. Nonetheless, Menzies had personally assured his MI5 counterpart, Sir Dick White, that his protégé could ‘not possibly be a traitor’.30 He made it clear to Philby that he was leaving with honour, awarding him a generous £4,000 payoff. Newly unemployed, he retreated to a cottage in the countryside. MI5, still suspicious, bugged his phones. All they heard were a series of calls from former MI6 colleagues wanting to commiserate.

The whereabouts of Burgess and Maclean became the subject of frenzied speculation in the summer of 1954, after a KGB colonel defected in Australia and claimed to have evidence not just that the pair were living in the Soviet Union, but that they had been tipped off about Maclean’s imminent arrest by a ‘third man’ who was a British official. MI5 and MI6 both started lobbying the foreign secretary: MI5 urging him to go public in the hope of flushing out Philby; MI6 assuring him the whole thing was just a vendetta got up by their domestic rivals. Menzies’ successor as ‘C’, Sir John Sinclair, blustered: ‘It is entirely contrary to the English tradition for a man to have to prove his innocence… in a case where the prosecution has nothing but suspicion to go upon.’31

Across the Atlantic, the bombastic and deeply peculiar head of the FBI, J. Edgar Hoover, had got a bug up his ass about the whole affair, and decided to leak Kim Philby’s name to the New York Sunday News. Equally uninhibited, thanks to the custom of parliamentary privilege (which means no one can sue for libel over any remarks made in the Commons), was Labour MP Marcus Lipton. He stood up on 25 October 1955 and asked: ‘Has the Prime Minister made up his mind to cover up at all costs the dubious third man activities of Mr. Harold Philby…?’32 As foreign secretary, Harold Macmillan was instructed to make a statement in response. In a briefing paper circulated to the cabinet he maintained that it would be very unwise to start too scrupulous an inquiry into the whole affair. ‘Nothing would be worse than a lot of muckraking and innuendo,’ he fretted. ‘It would be like one of the immense divorce cases which there used to be when I was young, going on for days and days, every detail reported in the press.’33

This was certainly the view of the man chosen to brief Macmillan ahead of the debate, MP Richard Brooman-White, whose career might be summarized as Eton, Cambridge, MI6, Conservative Party. He was an old friend of Philby, and, in the double agent’s own words, was one of those who was ‘absolutely convinced I had been accused unfairly. They simply could not imagine their friend could be a communist. They sincerely believed me and supported me.’34 The fact that everyone had thought exactly the same about Donald Maclean does not seem to have occurred to them.

‘No evidence has been found to show that Mr Philby was responsible for warning Burgess and Maclean,’ Macmillan assured the House. ‘While in Government service he carried out his duties ably and conscientiously. I have no reason to conclude that Mr Philby has at any time betrayed the interests of this country, or to identify him with the so-called “third man,” if, indeed, there was one.’35

Lipton and a few Labour colleagues protested. ‘Whoever is covering up whom and on what pretext, whether because of the membership of a circle or a club, or because of good fellowship or whatever it may be, they must think again and think quickly,’ said Frank Tomney, a trade unionist who had walked the whole way from Bolton to London in search of work in the thirties.36 He was howled down by the Tory benches, where a taunting chant of ‘Say it outside!’ was soon got up. Philby himself repeated the invitation to Lipton at a press conference the following day, and the MP had little choice but to withdraw the accusation, saying he ‘deeply regretted’ it.37 ‘The last time I spoke to a communist, knowing him to be a communist, was some time in 1934,’ Philby lied to the assembled journalists, all of whom were utterly charmed.38

Burgess and Maclean finally surfaced in Moscow the following February, when they were triumphantly presented to the world’s press to read a script about how they ‘came to the Soviet Union to work for the aim of better understanding with the West’.39 Philby’s luck did not run out for a further seven years. Following up a tip-off from yet another defector, an old friend of Philby’s from his MI6 days, Nicholas Elliott, was dispatched to Beirut, where Philby was working as a journalist and hitting the bottle in a big way – like Burgess and Maclean before him. Philby finally shared all in January 1963 with the words: ‘Okay, here’s the scoop.’40 After providing Elliott with a signed confession running to several pages, he contacted his KGB handler and was quietly smuggled on board a Soviet freighter. Two months later, the British government was forced to admit that he, too, had gone missing. And in June, beneath the provocative headline, ‘HELLO, MR PHILBY’, the state-owned Russian paper Izvestia revealed that he was not only a resident of Moscow, but a newly sworn citizen of the Soviet Union. He died in 1988 and was buried with a full KGB honour guard, just ahead of the collapse of the country and system he had devoted his life to.

In 1968 a trio of Sunday Times journalists published The Philby Conspiracy, which for many years stood as the definitive work on the scandal. By way of demonstrating how most people grew out of their youthful dalliances with communism and went on to lead the most respectable of lives, the book mentioned the names of a few other Cambridge friends: ‘men who are now diplomats, millionaires, bulwarks of the Church, the Establishment and the established’. One such was ‘Anthony Blunt, now Keeper of the Queen’s Pictures’.41 A decade after the book’s publication, Margaret Thatcher was forced to confirm in the Commons that Blunt had also spied for the Russians. He had even helped to organize Maclean’s defection to Moscow. Although the British security services had allowed him to keep his job at Buckingham Palace, they had known he was a Soviet agent since 1964 – a year after Philby had been unmasked, and a full thirteen years after Maclean had eluded his half-hearted pursuers.

If a mistake is worth making, it is worth making again and again.

‘I want to say this on the question of foreknowledge, and to say it quite bluntly to the House, that there was not foreknowledge that Israel would attack Egypt – there was not.’

Sir Anthony Eden,House of Commons, 20 December 1956

Anthony Eden needed an excuse. He knew full well that Colonel Gamal Abdel Nasser, who had seized power in Egypt in a coup in 1954, was bad news. When, two years later, he nationalized the Suez Canal – a vital trade route controlled by the UK since the Victorian era – it only went to prove exactly what sort of a man Nasser was. ‘We all know this is how fascist governments behave, and we all remember, only too well, what the cost can be in giving in to fascism,’ thundered the prime minister in a BBC broadcast on 8 August.42 Eden had made his name as a vocal opponent of Neville Chamberlain’s policy of appeasing Hitler back in the thirties; now, he was determined to refight the defining battle of his youth.

No matter that Nasser did not intend to stop shipping using the canal – he needed the income from it to fund his plan for a hydroelectric dam on the Nile – or that he offered to keep on all its staff on the salaries and terms they had previously enjoyed and pay all shareholders the full price of their shares as recorded on the Paris stock exchange the day before his nationalization. The canal, which linked the Red Sea and the Mediterranean, knocking more than four thousand miles off a journey that would otherwise take ships the full length of Africa and back again, was too important to trust to a man who, for all Eden’s talk of fascism, was leaning dangerously leftwards and making friendly overtures to both the Soviet Union and China. More than half of Europe’s oil came through the canal, giving Nasser an effective stranglehold on Britain’s energy supplies. More to the point, like so many former colonial subjects, he was challenging British power, and as such he needed to be swiftly and definitively crushed.

What Eden lacked was an actual justification for an aggressive response. ‘We should be on weak ground on basing our resistance on the narrow argument that Colonel Nasser had acted illegally,’ reads a cabinet briefing note drawn up by government lawyers. ‘From the legal point of view, his action amounted to no more than a decision to buy out the shareholders.’43 What they needed, concluded the special Egypt Committee that Eden convened of his most hawkish colleagues, was ‘some aggressive or provocative act by the Egyptians’.44 But as the months went past, and the British Army drilled its troops and painted its vehicles in desert colours, Nasser obstinately refused to provide one.

So they had to create one themselves. On 14 October two French diplomats visited Chequers. Eden told his private secretary that there would be ‘no need’ for any notes to be taken of their meeting and the visitors’ book was quietly doctored to excise their names. Six days later the foreign secretary, Selwyn Lloyd, cancelled his official engagements, claiming to be ill. Instead of resting up at home he caught a flight from RAF Hendon to a military airfield in France. From there he was driven to a villa in the Paris suburb of Sèvres where the French prime minister, Guy Mollet, and the Israeli prime minister, David Ben-Gurion, were waiting. France, which had overseen the canal’s construction in the nineteenth century, and which remained a major shareholder right up until Nasser’s action, was committed to military action alongside Britain; the top secret agreement, signed in the villa’s kitchen two days later with a champagne toast, brought Egypt’s neighbour fully on board. The existing peace between Israel and Egypt was already uneasy: Nasser had demanded ‘Israel’s death’ a year before.45 But, thanks to the terms of the Protocol of Sèvres, it would be Israel which struck first.

The agreement did not beat about the bush. And it came with a full timetable and detailed instructions:

1. The Israeli forces launch in the evening of 29 October 1956 a large scale attack on the Egyptian forces with the aim of reaching the Canal Zone the following day.

2. On being apprised of these events, the British and French Governments during the day of 30 October 1956 respectively and simultaneously make two appeals to the Egyptian Government and the Israeli Government on the following lines:

A. To the Egyptian Government

a) halt all acts of war.

b) withdraw all its troops ten miles from the Canal.

c) accept temporary occupation of key positions on the Canal by the Anglo-French forces to guarantee freedom of passage through the Canal by vessels of all nations until a final settlement.

B. To the Israeli Government

a) halt all acts of war.

b) withdraw all its troops ten miles to the east of the Canal.

…It is agreed that if one of the Governments refused, or did not give its consent, within twelve hours the Anglo-French forces would intervene with the means necessary to ensure that their demands are accepted.46

On 29 October, just as agreed, Israeli forces invaded Sinai, the peninsula between the Egyptian border and the Suez Canal. The next day, putting on their most surprised faces, the British and French governments demanded a ceasefire from both sides. When Nasser refused, British planes unleashed hell, practically destroying the Egyptian air force. On 5 November ground troops went in.

The invasion had one immediate effect – the exact effect Eden had been trying to avoid: Nasser did finally close the canal, scuttling all forty ships that were currently in it for good measure. The canal would not reopen to shipping until well into the following year. But the invasion had a second unwanted consequence: it whipped up an unprecedented frenzy of condemnation back home. The prime minister was booed in the Commons as he arrived to debate a Labour motion: ‘That this House deplores the action of Her Majesty’s Government in resorting to armed force against Egypt in clear violation of the United Nations Charter’.47 Eden was forced to fall back on his own record to defend himself. ‘I have been personally accused of living in the past and being too much obsessed with the events of the ’thirties,’ he told baying MPs. ‘However that may be, is there not one lesson of that period which cannot be ignored? It is that we best avoid great wars by taking even physical action to stop small ones.’48 This overlooked a fairly enormous point: that Eden had actually started the small war to justify an action he had been itching to take for months.

But as yet, no one knew this. All they knew was that almost everyone seemed to think it had been a bad idea. Eden’s protests that he had taken nothing more than a ‘police action’ in intervening to ‘separate the belligerents’ cut little ice. There were protests against the war across the Middle East, and as far afield as China and Indonesia. The UN General Assembly convened its first emergency session, with sixty-four nations voting to demand an immediate ceasefire. Thirty thousand people crowded into Trafalgar Square to hear Labour’s shadow foreign secretary, Aneurin ‘Nye’ Bevan, spit fire at the prime minister: ‘If Sir Anthony is sincere in what he says – and he may be – then he is too stupid to be Prime Minister.’ The chant ‘Law not war!’ rang out around the square. A breakaway group marched down Whitehall singing, ‘One, two, three, four, we won’t fight in Eden’s war.’ They had to be held back by police at the entrance to Downing Street.49

It wasn’t the domestic protesters that did for Sir Anthony; it was the Americans. The US had been quite happy to intervene when Iran’s first democratically elected leader, Mohammad Mosaddeq, had tried a similar trick in 1951 and seized control of British-owned oil companies within his borders. The CIA had fomented a revolt which ended with Mosaddeq in prison and a much more ‘friendly’ regime in Tehran that didn’t bother with silly notions like voting. But this time, Dwight D. Eisenhower was president of the US, and he had been clear from the outset that he (and by extension, America) wanted nothing to do with military action in the region. ‘I hope that you will consent to reviewing the matter once more in its broadest aspects’ was Ike’s magnificently diplomatic message to Eden when he learned the Brits were determined ‘to drive Nasser out of Egypt’.50 In the White House, he was said to use somewhat more ‘barrack-room language’ to describe Eden’s decision. But the prime minister and his colleagues seemed to have their fingers in their ears. ‘We must keep the Americans really frightened…. Then they will help us to get what we want,’ wrote Chancellor Harold Macmillan in his diary after a particularly discouraging conversation with the US secretary of state early in the crisis.51

The problem was a massive and disastrous overestimation of Britain’s influence in global affairs a decade after World War II. Eden, Macmillan and the other cabinet hawks had failed to notice that the world had rearranged itself: there was a new war on, a Cold one, in which the UK would be no more than a minor and subservient player. Treaty obligations threatened to draw America into the conflict on Egypt’s side: the USSR was already threatening to pile in and ‘crush the aggressors by the use of force’.52 Eisenhower finally put the kibosh on it all when he threatened to invoke oil sanctions against Britain unless they withdrew. Having already managed to stop supplies via the canal itself, the country simply would not be able to get by if it lost the rest. (As it was, petrol rationing had to be reintroduced later in the month.)

‘That finishes it!’ remarked Macmillan, finally getting the message.53 A ceasefire was announced on 6 November, by which point nearly one hundred British and French soldiers had lost their lives. When the full and humiliating British withdrawal from the canal zone was announced on 22 November, it was not Eden who broke the news to the Commons: pleading ill health, he had handed over the reins to his colleague Rab Butler and gone off to recuperate in the Jamaica home of his friend Ian Fleming, creator of James Bond, whose undiplomatic adventures overseas never seemed to end like this. Eden finally resigned as prime minister the following January. Suez finished him.

He continued to lie through his teeth about his foreknowledge of the invasion,54 but the evidence was out there. Ben-Gurion and his team had insisted on each party taking away a written copy of the Sèvres protocol: the last thing the Israelis wanted was for their European allies to have second thoughts and abandon them after they had fulfilled their half of the bargain. It would not be until twenty years later that one French and one Israeli official who had helped negotiate the protocol spoke out about its existence, and not until 1996 that the Ben-Gurion archives in Israel released the only surviving copy, which had been kept under lock and key ever since.