7,19 €

Mehr erfahren.

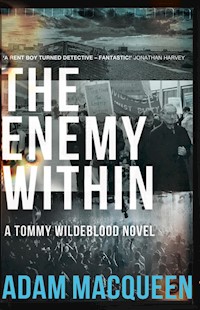

- Herausgeber: Lightning Books

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

The prime minister, the terror plot of the decade and an ex-rent boy who knows too much 'Accomplished and gripping' – The Observer It's 1984. Tommy Wildeblood, hero of Beneath the Streets, has put his days as a Piccadilly rent boy and scandal-hunting sleuth behind him, to study at the radical Polytechnic of North London. During a pitched battle against National Front infiltrators at the Poly, he meets handsome young Irishman Liam and embarks on the sort of romantic relationship he never thought he would have. But is it too good to be true? Liam's abrupt disappearance prompts Tommy to question how much he knows about his new lover. Dusting off his old sleuthing skills, Tommy's hunt for Liam takes him into the dark and violent netherworld of radical politics. As his search moves to an explosive climax, he finds himself in danger of carrying the can for one of the most shocking events of the decade. With the twin spectres of Aids and nuclear armageddon never far away, The Enemy Within is a gritty thriller built around a story of love in terrifying times. It captures the unique spirit of a dark and brooding age, with a supporting cast including Derek Jarman, corrupt Trotskyist leader Gerry Healy, a young Jeremy Corbyn and even Maggie Thatcher herself.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Ähnliche

ADAM MACQUEEN has contributed to Private Eye since 1997. He wrote the bestselling history of the magazine which was published in 2011, and edited the recent sixtieth anniversary celebration compiling the best of its contents over the years. He has also been on the editorial team of Popbitch and The Big Issue. His books include The Prime Minister’s Ironing Board and The Lies of the Land: An Honest History of Political Deceit. The King of Sunlight, his biography of the soap manufacturer William Hesketh Lever, was named by The Economist as one of its books of the year. His first novel Beneath the Streets, in which he introduced the character of Tommy Wildeblood, was longlisted for the Polari Prize.

Praise for Beneath the Streets

‘After I finished writing A Very English Scandal, I took a solemn vow — that I would rather spit-roast my own offspring than read anything else about the Jeremy Thorpe Affair. Seldom have I gone back on my word with more pleasure. As boldly conceived as it is vividly realised, Beneath the Streets is a delight’

John Preston, The Critic

‘A gripping thriller, interwoven with a really important thread about the condition of being gay in the 1970s’

Harriett Gilbert, A Good Read, BBC Radio 4

‘Adam Macqueen’s gripping debut novel is based on a provocative counterfactual question... He depicts his grim milieu engagingly – the 70s have seldom seemed so grotty and threatening – and this very English scandal has wit and invention to spare’

The Observer

‘Really well done. The detail and the authenticity is all there: London as a really scary, edgy, ugly place. The atmosphere is brilliant... As a portrait of a world I thought it was really fantastic, and I also read it with my computer by my side because I was constantly looking up the real-life figures and I was constantly shocked and amazed by how much of this is true’

David Nicholls

‘What if Jeremy Thorpe had succeeded in murdering Norman Scott? That’s the gripping premise behind this smart story of corruption, murder and establishment cover-up’

iPaper, 40 best books of the year

‘Adam Macqueen’s excellent debut thriller takes us back to 1976, a time of very British scandals. Former rent boy Tom Wildeblood is a thoroughly likeable hero, and the seedy allure of the period is convincingly rendered, while the plot skilfully mixes fact with fiction’

Mail on Sunday

‘A wonderfully evocative walk on the wild side of 1970s London. Darkly comic and deeply moving. A breathtaking, heartbreaking thriller’

Jake Arnott

‘Ticks all the boxes for me. Gay history. Jeremy Thorpe. And a rent boy turned detective called Tommy Wildeblood. Fantastic’

Jonathan Harvey

‘Agripping and occasionally hilarious depiction of what, up to this year at least, must have been the craziest period of modern British politics. The twist, on literally the last page, is superb. While some 1970s scandals were played out beneath the streets, some were hiding in very plain sight’

Law Society Gazette

‘A thrilling read...incredibly powerful’

Nina Sosanya

‘A fucking fantastic read. A gripping what-if thriller, packed with vivid period detail and page-turning twists. To find myself actually making an appearance in the final chapter was just cream on the cake’

Tom Robinson

‘A page-turning mystery, skilfully plotted and filled with tension. Lifts the lid on 1970s subculture to spine-tingling effect’

Paul Burston

‘A thrilling and brilliantly imaginative novel. It takes you into the secret world of Soho in the 1970s. But then suddenly it opens another door into the hidden world of violence and corruption that still lies underneath the England we know today’

Adam Curtis

‘Stonkingly good’

Rose Collis

‘Wonderfully evocative…darkly funny…deliciously believable’

Scene Magazine

Published in 2022

by Lightning Books

Imprint of Eye Books Ltd

29A Barrow Street

Much Wenlock

Shropshire

TF13 6EN

www.lightning-books.com

Copyright © Adam Macqueen 2022

Cover by Ifan Bates

Typeset in Minion Pro and Bebas Neue

The moral right of the author has been asserted. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN: 9781785632341

For Emily Travis,for being inspirational, and remaining so for so long.And for Adrian, for the exact same reason.

Many of the people in these pages, from Trotskyists to Tories, share their names and certain other biographical details with real people.

That is all they share.What follows is a work of fiction.

Contents

PROLOGUE

PART ONE

ONE

TWO

THREE

FOUR

FIVE

SIX

SEVEN

EIGHT

NINE

TEN

ELEVEN

TWELVE

THIRTEEN

FOURTEEN

FIFTEEN

SIXTEEN

SEVENTEEN

EIGHTEEN

NINETEEN

TWENTY

TWENTY-ONE

TWENTY-TWO

TWENTY-THREE

TWENTY-FOUR

PART TWO

ONE

TWO

THREE

FOUR

FIVE

SIX

SEVEN

EIGHT

NINE

TEN

ELEVEN

TWELVE

THIRTEEN

FOURTEEN

FIFTEEN

SIXTEEN

SEVENTEEN

PART THREE

ONE

TWO

THREE

FOUR

EPILOGUE

AFTERWORD

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

PROLOGUE

12 OCTOBER 1984

It was freezing on Brighton seafront, the numbing wind carrying a good dose of the sea’s brine. I could see the lights of the pier, twinkling up ahead. I pushed my frigid hands deep into my pockets and, head down, strode on. I was walking as fast as I could, having to will myself not to break into a run: I knew if I arrived at the police cordon breathless and sweaty it was bound to arouse suspicion, prompt unwelcome questions. Whatever happened, I needed to get in there unnoticed.

Get in, do what I had come here to do, and hopefully – there was absolutely no guarantee of this – make it out of the building again alive. I glanced at my watch. It was after one am already, but with all the adrenaline pumping through me it somehow didn’t feel like the middle of the night.

I spotted the hotel a long way off. It was unmissable: huge, like a giant wedding cake, tier upon tier, with elaborate cast-iron balconies running the length of its front on every floor. The whole thing was lit by floodlights shining up from the semi-circular lawn in front of it: the rooms must have very good curtains or there was no way any of their guests would ever get any sleep. Its name was picked out across the lowest balcony in gold letters that must be almost as tall as I was: GRAND.

Outside it the road was blocked with bollards, and I could see uniformed policemen stopping cars driving along the seafront. I made sure to turn off the chilly promenade well before any of them could spot me, and instead headed inland, zig-zagging through the streets until I spotted the concrete bulk of an NCP car park looming above the rooftops. If what I had been told was correct, the staff entrance was down the side of it, and barely guarded at all. My disguise should be enough to get me inside. If I was lucky. And I only needed to be lucky once.

There was an alleyway running along the edge of the multi-storey, just as I had been told. A single crash barrier across it, and a bored-looking policeman standing there. Deep breath; keep walking; stay as casual as possible. Try to look like I did this every day.

‘Morning!’ I said as I approached him, trying to keep my voice steady and holding the ID card I had been given out in front of me like a talisman. My heart was beating so fast and so loud I was surprised he couldn’t hear it in the still night air.

‘Cor, they work you lot nearly as hard as they work us, don’t they?’ he said cheerily, taking in the bow tie and crisp white shirt that made up my waiter’s outfit. He barely glanced at the card in my hand as he shifted the barrier aside to let me through. He had a ruddy, friendly face; quite handsome. Not so much older than I was. Probably had a family waiting for him back home. But I forced myself not to think about that right now.

‘No rest for the wicked!’ I quavered in a voice half an octave higher than my usual one, and I walked on.

A blast of warm air greeted me as I approached the shabby double doors at the end of the alleyway. Great extractor fan vents on the back of the building were pouring out heat and a thick fug of fatty meat smells. The back of the building could hardly have been more different from the fancy frontage: the alley was lined with bins, pallets, broken-down cardboard boxes and empty cooking-oil cans. Two of the round drums separate from the rest served as the seats in a smoker’s area, judging by the dozens of cigarette butts scattered around them. Assuming the policeman’s eyes were still on me – there was sod all else to look at at this time of night – I tried hard not to break pace as I approached the doors, pushing them confidently and mouthing a silent thanks as they swung inwards. And I was in.

I found myself in a dingy hallway, the linoleum floor all but covered with overflowing wicker laundry baskets. On the right was a kitchen storeroom lined with wire shelves holding enormous cooking pots from floor to ceiling; on my left rose a bare flight of stairs. Somewhere up there, several floors above me, among hundreds of other sleeping people, right now, was Margaret Thatcher. And if I, Tommy Wildeblood, had got things right, then she, her entire cabinet, and God knows how many other supporters of her vicious disgrace of a government were all going to die tonight.

PART ONE

SPRING 1984

ONE

There was a sense of restless tension in the entrance hall. You could actually feel it running through the crowd, squashed tight shoulder to shoulder as we were; it surged and ebbed each time the doors to the street swung open, everyone craning their necks to see if this time it was him.

It wasn’t, of course. His lecture wasn’t due to start for another half an hour, and it would be suicide for him to try to get in before that. He would be taking his life in his hands turning up at all, given the mood of the building: great long banners had been unfurled from the windows on the second floor reading No Nazis at NLP, Black and White Unite and Fight and, just in case this wasn’t personal enough, Harrington Not Welcome Here. Inside, someone had unfurled an old Anti-Nazi League banner over the side of the staircase and angled it so that the arrow pointed firmly out of the front door, which was a nice touch, even if the lopsided position meant that yards of spare material pooled on the stairs themselves and made an accident even more likely. The staff had already delivered a stern warning about the safety issues of so many of us thronging the stairs, but not a single person had budged. If Patrick Harrington, nineteen-year-old member of the National Front, wanted to get to his Philosophy lecture on the first floor, he would have to get past every one of us, black, white and every shade in between. We’d made sure every other entrance to the building was blocked off too. There was only one lesson that was going to be taught today.

The crowd convulsed once again as the doors opened, and for a second I lost my footing, carried sideways by the sheer force of people on either side. It took me a moment to get upright enough to see that it was only Richie, the president of the student union, dressed in an ex-army jacket with Rock Against Racism emblazoned across the back, which he kept for special occasions, and the pork-pie hat he wore to disguise the fact he’s going prematurely bald. ‘All right,’ he hollered, holding up his arms for silence. ‘I’ve spoken to the copper in charge’ – a chorus of boos, which he rode out with every appearance of enjoyment – ‘and he’s made it very clear that under the terms of the court injunction we are all banned from any form of protest outside the building and anyone who goes one step further than the doors behind me is going to get arrested.’ There was another bout of booing, accompanied by shouts from way back by the cafeteria of ‘can’t hear!’ and ‘speak up!’

An idea struck me and I called out to Richie, but he couldn’t hear me, so I stuck two fingers in my mouth and whistled, which ensured about half of the heads in the hallway turned in my direction. I gestured at the staircase – ‘Over here!’

The crowd parted to let a grateful Richie through, and he hauled himself up onto one of the parapets that extended from each step outside the curlicued ironwork of the banisters, holding on tight as he picked his way a few steps higher until he could be seen well over the heads of everyone beneath. A hush fell as he started speaking again. ‘As I was saying, Maggie’s boot boys are out in force today. It looks like the state is nearly as frightened by us exercising our democratic rights as it is by the miners!’

A great roar of approval echoed through the hallway. The right might like throwing questions around about how exactly Arthur Scargill chose to conduct the strike, but there were no such issues here: the student union had unanimously voted to defy the orders of the High Court that Harrington, such a keen spreader of fascist ideas that he was deputy editor of National Front News, should be allowed to enter all premises of the polytechnic and enjoy his education ‘without fear or harassment’ for as long as he remained a matriculated student here. When he’d turned up a fortnight ago brandishing his injunction, we’d torn it up on the doorstep and thrown it back in his face. It had been enough to send him on his way then, but this time he’d brought backup.

‘These state soldiers have made it very clear that they won’t allow us take our protest out onto the streets,’ Richie continued, his face beginning to turn as red as his hair as he stoked up the rhetoric. ‘Make no mistake: in 1984 we are trulyliving in Orwell’s world!’

There was another ripple of approval from the crowd, which masked my own sigh. It was only May, but Orwellian must already qualify as the most over-used adjective of this particular year, especially by people who have never actually read any of poor old Eric Blair’s books.

‘But don’t worry, comrades!’ Richie thundered on. ‘For our part I made it very clear to the officer in charge that we will be exercising our democratic right to protest within polytechnic premises to the full!’ The biggest roar yet echoed around the building. I could actually feel the banister on which I was leaning – half ready to catch hold of Richie if he slipped – vibrating beneath my hand.

‘Comrades, we stand united!’ he barked, visibly swelling from the reaction he was getting. ‘I say this to you now: the state can issue all the injunctions and orders it likes, and it can send in as many of its shock troops as it wants to enforce them, but we will never – never – allow the National Front to get a foothold in this college, and endanger the brothers and sisters of all colours who study here peacefully in our community!’

They didn’t sound very peaceful right now, as a deafening bout of cheering evolved into a chant of Fascists Out! Fascists Out! Fascists Out!

Richie stayed up on his eyrie for a few seconds, milking the reaction, before clambering down and beckoning me close so I could hear him over the row. ‘We could really do with someone out there to give us an early warning when he’s on his way, Tommy.’

I sighed. Richie had found out I had more than a little experience of being arrested when I’d dispensed some advice to my fellow protesters ahead of an Anti-Apartheid Movement demo in my first year. I didn’t mind him knowing – it was good to put the kickings and abuse I’d received in police cells and interview rooms over the years to work in a good cause – but I slightly resented the implication that it meant I wouldn’t mind it happening again.

‘There’s loads of guys upstairs hanging out of the windows,’ I pointed out. ‘Can’t they just get a message down to us when they see Harrington coming?’

‘In the language labs?’ He shook his head in disgust. ‘They’re Sparts. They say they’re running their own, independent occupation of the department and they won’t cooperate with us.’

‘Oh for fuck’s sake.’ The elections to the student union executive this year had ended with a landslide for the Socialist Organiser slate, and the Spartacist Society candidates had been causing trouble ever since.

Richie gave me a pleading look that suddenly reminded me that, for all his bluster, he was a good five years younger than I was, and I shrugged and gave in. Besides, I’d had an idea. ‘I’ll see what I can do. You wait just inside. Keep the door ajar and listen for my whistle, yeah?’

We shouldered our way through the restless crowd and I pushed on through the glass-panelled doors into the entrance porch of the building. The police certainly weren’t messing around. There had been three police vans parked outside when I’d arrived an hour earlier: now back-to-back paddywagons filled the entire opposite side of the street, and a string of officers were lined up in front of them at six foot intervals as far as I could see in either direction. Every single one of them had the look of a man who was up for a ruck. For now they were just in their ordinary uniforms, but the back of one of the vans was open and I glimpsed racks of riot shields and helmets hanging inside as I trotted down the steps and turned right, aware of the need to keep moving.

I was glad I’d had the foresight to pack my army surplus haversack with books and files when I came out this morning: I’d vaguely thought I might get some studying done in the library once all this was over, and unlikely as that now seemed, they would at least serve as evidence I was here on normal university business. Let any of the cops stop me and we could see what they made of Shakespeare and the Traditions of Comedy and Criticism and Ideology. Actually, scratch that: Terry Eagleton probably counted as dangerously subversive literature.

The police had a photographer with them. I sensed his long lens following me down the road and couldn’t resist giving him a wave, though I restrained myself from blowing my customary kiss. There were a couple of skinheads in bomber jackets hanging around on the fringes of the group too, who were almost certainly NF pals of Harrington’s. There didn’t seem to be anything in the injunction preventing them from hanging around outside, I noticed.

I’d got almost all the way up to the main road before I spotted the man I was looking for – a slightly downtrodden figure wearing a green anorak and holding a pile of newspapers draped over one arm. There appeared to be just as many of them left as when I’d passed him on the way in to the Poly an hour earlier.

‘Hi, Dex!’ I said, with unwonted enthusiasm.

‘Oh, all right Tommy.’ He squinted at me through thick glasses. ‘How’s it going?’

‘All right. Listen, can I give you a hand selling them?’ A wad of newspapers on my arm would give me the perfect excuse to hang around outside the Poly, or at least ensure enough arguing time for me to get the real job done.

Dexter’s eyes lit up. ‘Yeah, of course. Great!’ He had been in the same year as me doing sociology, and though he’d left the Poly the previous summer, he had regularly turned up outside flogging papers on behalf of the group he was involved with. I’d assumed it was the Socialist Worker – you can’t throw a brick at any protest without hitting someone selling the Socialist Worker – but as he passed over a handful I realised it was something totally different: a brightly coloured tabloid that looked a bit like the Sun or Mirror except that it was way brighter and more colourful. Under the headline GENERAL STRIKE NOW the front page had an eye-popping colour photo of an enormous crowd of people marching beneath bright trades union banners. I didn’t even know you could get newspapers in colour. It was called News Line.

‘Cheers, mate.’ I overcompensated with my enthusiasm out of guilt. Dexter hadn’t exactly been the most popular person at the Poly – he was a bit boring, he didn’t drink, and his personal hygiene was another reason you never wanted to get stuck with him at a party – but he was all right in his own slightly earnest way. ‘This what you’re up to these days, then?’

‘Mostly,’ confirmed Dexter glumly. ‘Still no jobs going, so I’m spending most of my time selling papers. I’ve got a shift outside the Ever Ready factory at lunchtime, but I thought it might be worth coming down here beforehand – what with all this.’ He gestured towards the front of the Poly.

‘Mm. Good thinking.’ I was distracted, scanning the street for Patrick Harrington. I’d only actually seen him once – no one could remember him ever showing his face at the Poly before all this blew up.

‘I don’t mind, of course,’ Dexter continued, oblivious. ‘I mean, I want to do my bit.’

‘Uh-huh.’ A couple of the policemen on the opposite side of the street were conferring and giving us the evil eye, obviously deciding whether or not to come over. ‘News Line!’ I shouted in my best impression of an Evening Standard barker. ‘Get your News Line here, hot off the press!’

Dexter was staring at me in amazement. I wasn’t surprised he didn’t manage to sell many papers.

‘I’ll take one,’ said a voice to my left. And that was the very first time I saw him.

TWO

Even after everything that came after, I’m not going to pretend he actually took my breath away or anything like that, but there was a definite significant moment when our eyes met. His were a deep brown, peeping out beneath long dark eyelashes beneath even longer, darker hair, which was nicely looked-after without straying too far into George Michael territory. Full, pouting lips, and great skin: that was one of the first things that struck me about him. Most of my fellow students haven’t outgrown their acne yet and those who have seem to make a virtue out of not washing or shaving properly: by contrast his cheeks were so peachy you just wanted to run your fingers all over them, followed by your lips and, if possible, certain other parts of your body. But I’m getting ahead of myself. I didn’t even know his name at this point.

‘How much?’ he said, and gave me a smile that left me momentarily unable to speak. He was wearing a bomber jacket festooned with badges, and I could just make out a yellow t-shirt underneath it which suggested that either the Anti-Nazi League arrow or the Nuclear Power sun would be revealed once the jacket was unzipped. Stop thinking about unzipping him, I reminded myself. You’ve got a job to do. There was still no sign of Harrington.

‘Er… I…’ I clumsily slid one of the papers from the pile, scanning the front page for a price.

‘16p,’ came the unimpressed tones of Dexter from beside me.

‘Cheap at twice the price.’ The stranger flashed me that disarming grin again and dug into the pocket of his jeans to pull out a shiny new 20p coin.

‘Oh – I’m not sure if I’ve got – have you got change, Dexter?’ I was all over the shop. I didn’t seem to be able to string a sentence together. My fellow seller extracted a plastic bag full of coins out of the pocket of his anorak, but our customer waved it away.

‘Don’t worry. Keep the change. All in a good cause, eh?’ That was surely an Irish accent. It was gorgeous.

‘Thank you,’ confirmed Dexter, plucking the coin pointedly from my own hand and dropping it in with the rest of them. I didn’t even look round.

Our customer folded the paper and shoved it under his arm, but thankfully showed no sign of moving on just yet. ‘Bit of a smell of bacon round here this morning, eh?’

I managed to tear my eyes away from his face for just long enough to follow his gaze to the police line. ‘Yeah!’ I spluttered, then, with a bit more bravado than was probably wise, added ‘Bloody pigs!’ The nearest policeman shot a sharp glance in our direction.

‘I take it Harrington hasn’t arrived yet?’

So he knew what we were all here for. That was good. ‘No…no. He’s due any minute.’

‘Good. I was worried I’d be late for the fun. I was expecting to see a few more people out on the street.’

‘No, we’re…concentrating our forces inside,’ I told him. ‘Going to make sure there’s no chance of Harrington breaching the building.’

‘Right.’ He nodded approvingly and then, as he glanced over my shoulder, his nice smile evaporated. ‘Heads up.’

I turned. The constable had broken away from the line and was crossing the road towards us, a very unfriendly look on his face. ‘Let’s move it on please gents.’

‘We’re selling newspapers,’ I said firmly, holding up my pile of News Line as proof.

‘I don’t give a shit if you’re selling rubber johnnies to vicars, we’ve got orders to keep the public highway clear.’ A couple of other policemen had detached themselves from the line and started over to join their colleague. I was very aware of the truncheons dangling at their belts.

‘We’ve got every right to be here,’ piped up Dexter, and suddenly the policeman lost all interest in me. You could actually see his whole body language changing as he clocked that a black man was talking back to him. He straightened up by several inches and took up a wide-legged stance in front of Dexter – who suddenly looked very small in his anorak and glasses – and his hand actually moved to his baton handle. I’m as ready to cite Sigmund Freud as the next English student, but this seemed a bit too obvious.

‘Is that right, chummy?’ he hissed, practically into Dex’s face.

‘OK, we don’t want any trouble,’ I said, nervously moving to try and get myself in between them. But as I did so, through the gap between their bodies I glimpsed a figure approaching. A pinch-faced young man, neat hair, white collar open over a patterned jumper, swinging a smart leather briefcase by his side: totally normal-looking if you didn’t know he was actually a high-ranking figure in the closest thing we had to a Nazi party in this country. I was familiar with that Hannah Arendt phrase about the banality of evil – it was one of the things you tried to drop into your final exams if you were hoping to get a first – but never before had I seen someone who so perfectly epitomised it. Forgetting all about everything else that was going on, I turned around, and for the second time that morning pushed my fingers into the corners of my mouth and whistled as hard as I possibly could.

Everything happened very fast after that. I suddenly felt a cracking pain across the back of my shoulder that sent me reeling forward towards the handsome stranger, who threw up his arms, a look of shock and dismay on his face. I stumbled into him, and as my face pressed up against his jacket my nostrils were suddenly filled with the pungent scent of him, something woody and exotic, with an undertow of the real man underneath that was completely intoxicating. And then there were hands gripping my arms and someone was yanking the pair of us apart. I realised it was a policeman dragging me backwards, and that another one had his hands on the stranger. I caught a brief glimpse of Dexter too, sprawling on the pavement with his papers flying and all the coins from his change bag scattering into the gutter, before a great roar went up from the Poly building that sounded like Highbury stadium on match day and everything went crazy.

The police line peeled away from the opposite side of the road, sweeping around us as we were dragged towards the rank of paddywagons. To my horror I watched the uniformed officers close in around Harrington and form what looked suspiciously like a guard of honour as he approached the building, but at that point I was manhandled to the ground and felt a pair of handcuffs closing around my wrists, and I only caught glimpses of what happened next. A dozen or so police togged up in the riot gear I had spotted earlier came clattering out from behind the vans to stand shoulder to shoulder at the ready by the polytechnic’s entrance – so the steps and the pavement outside were swamped with figures in uniform as the slight figure slipped between the outer doors.

The phrase ‘police state’ gets bandied around a lot these days; right now it looked pretty much bang-on. ‘Am I being arrested?’ I demanded of the unseen figure who was fastening my hands behind me. ‘Am I being arrested? You have to tell me what you’re arresting me for. I know my rights.’

‘Shut it,’ said a voice behind my ear, and I got a punch to the back of the head that made my chin slam into my chest and my eyes water. ‘You just assaulted a police officer – that’s what you’re being arrested for.’ He gave a nasty laugh, and then stepped over me and legged it across the road, unwilling to miss out on all the fun with his mates.

‘Christ,’ said a familiar voice, and I turned to see my handsome new friend sitting on the pavement a few feet away from me. His hands were cuffed behind his back as well. ‘Are you OK? That was quite a crack he fetched you back there. All you were doing was whistling!’

‘Yeah, fine,’ I said, furiously blinking away the tears and looking around for Dexter. ‘Where’s Dex? What have they done with him?’ I knew that if the police were getting slap-happy with white boys like me, they would be dealing out far worse to Dexter.

‘They took him behind that van,’ said the stranger, nodding towards the nearest vehicle. I could make out the sound of scuffling behind it, and I tried to shunt myself backwards from my seated position to be able to see what was going on, but at that point the noise from the Poly redoubled, and I turned to see the outer doors swing wide open and the riot cops surge forward and start to push their way into the building.

At that, all hell broke loose. There were screams from inside, and the figures at the windows above began a frenzied hail of abuse followed up with makeshift missiles –pens and other stationery mostly although a heavy tape recorder that I was surprised could squeeze between the safety guards on the window did come flying down at one point. I didn’t see where it landed.

There was a moment of Keystone Cops ridiculousness as more than a dozen officers seemed to be trying to force their way through the narrow entrance at once, their plastic shields impeding their way, but suddenly the tide turned and they were driven back down the steps, one of them stumbling and falling beneath his colleagues’ boots, as a wave of students burst out of the doors, propelled by pressure from behind as much as by their own volition.

I saw Richie, thrashing his arms – he’d lost his hat and his scalp showed blazing red – and his girlfriend Sonya, the Women’s Officer, next to him in her boiler suit, Kelvin, a handsome Trinidadian from the English department, and a couple of other people I recognised too before they were lost in the sea of blue engulfing the steps and everything was chaos.

By now there were plenty of other people out in the street: surreally, they included several little kids on BMXs who had appeared out of the council estate opposite and were doing wheelies up and down the street while shouting a mixture of encouragement and abuse at both sides in the battle.

The one person I didn’t see was Patrick Harrington, although afterwards someone said he had been whisked out of harm’s way in a panda car, sitting up front like a VIP. But by that point the rest of us were making our own rather different journey, stuffed like sardines into the back of a police van and taken away to be charged with obstructing the police in their duties by getting in the way of their truncheons, boots and fists.

THREE

It was less traumatic for me than it was for some of the rest of them. Like I say, I’ve got plenty of experience of being arrested – you don’t do four years selling your body on the Dilly without getting to know your way round a police cell or two – and although it had been a while, I still knew the routine practically off by heart. It was a lot worse for some: Dex and Kelvin in particular got a double dose of the rough handling that the rest of us were treated to, plus a pantomime from the desk sergeant about not being able to understand either of their accents even though Dex is as Brummie as they come. And I saw Sonya in tears too – but then she had trouble to look forward to at home as well because, although she doesn’t like to admit it, her mum is a magistrate and a Tory councillor back home in Worcestershire.

For my part I managed to do what I always used to do in these situations and detach myself from it all. It helped that none of it came as a surprise to me like it did to the others. In the old days I used to get hauled in just as often for things I hadn’t done as things I actually had. I’d also had far harder punches from policemen than the one I’d got today (though I had to admit my shoulder was aching, not helped by the handcuffs preventing me from giving it a proper roll round in its socket as it felt like I needed to do). I even managed to successfully get myself in the line behind my new friend at the custody desk, which gave me the opportunity to check out an arse that turned out to be just as peachy as his face and – this is a particular thing of mine – the most gorgeous nape, a slender neck rising to hair that tapered into a perfectly-razored line which I could just imagine the feel of against my lips.

His name was Liam Delaney, he told the desk sergeant when his turn finally came. I rolled the syllables silently around my mouth, enjoying the taste of them. Occupation: student, Polytechnic of North London, although I was certain I’d never seen him around our campus before – I would definitely have remembered – so he must be over at Holloway Road. Current address in Kilburn, permanent address in Belfast, so I was (mostly) right about Irish. I didn’t get much more than that because at that point I was called forward to give my own details to another officer, but the fact there were so many of us played to my advantage: they had to double us up and the two of us ended up sharing a cell.

‘Hello again,’ he said with a grin as I was ushered in and the door slammed and locked behind me. It had been a close-run thing: I’d had to rush through the surrender of my possessions for fear of ending up banged up with Richie instead, who was likely to spend the hours ahead badgering me to stand for the union executive because he’d fallen out with the current postgrad rep. He’d been on at me about it for weeks, claiming she was a ‘total Tory’. Sandra was actually a perfectly nice American, about as anti-Reagan as they come, but she did oppose Richie’s plan to donate union funds directly to the striking miners rather than just whatever we could get by shaking buckets, so he was determined to get rid of her, and he had decided I was the man to help him, whether I wanted to or not.

‘Hi,’ I grinned sheepishly. ‘Sorry about all this. All you were trying to do was buy a paper!’

‘It’s not your fault. I knew what I was getting into when I came over to join the fun this morning. I’m Liam.’ He held out his arm towards me: I couldn’t help noticing how all the different muscles on it stood out beneath a corona of fine dark hairs. I’d been wrong about the yellow t-shirt: it turned out to be one I hadn’t seen before, with a couple of palm trees on it and the slogan For a Reagan-Free Caribbean.

I took his hand and shook it, over-conscious of how it felt in mine. ‘Tommy.’

He raised an eyebrow. ‘That’s not what you told them out there.’

‘Oh!’ So he’d been eavesdropping on me, too: that was interesting. ‘No, I’m Alex officially, but everyone calls me Tommy.’

He let go of my hand and shifted up to make room for me on the mattress-covered slab that was the only place to sit in the cell. ‘Why so?’

‘Oh, it’s just a nickname really.’ I settled down beside him, trying not to smirk at the thought that we had only met an hour or so ago, and we were already getting into bed together. ‘I started using it years ago, and it’s kind of stuck.’ I wasn’t about to tell him the full circumstances, but sharing a little couldn’t hurt. ‘I used to go by Tommy Wildeblood.’ I still did, sometimes.

He turned his head to face me, his brow crinkling in thought. ‘Why so?’

Our current surroundings felt like a sign, so I took a deep breath and plunged in. ‘Peter Wildeblood was a gay man who was arrested in the 1950s. He went to prison, and then he wrote a book about it. It was pretty important to me for a while.’

This was an understatement. I’d carried Wildeblood’s book Against The Law around with me for years when I was selling myself on the Dilly, keeping it close to my heart and consulting it for advice like my own personal I-Ching – with surprisingly effective results on occasion. My copy, liberated from my local library when I was just a kid, had long since got too tattered to accompany me any more, but it still had pride of place on my bookshelves back at my bedsit. ‘And it’s for Oscar Wilde a bit, too,’ I added, just to make sure he’d definitely got the message. It couldn’t hurt that Wilde was Irish – a fact I’d only become aware of embarrassingly late in my English degree.

‘Interesting.’ His impression was inscrutable. It wasn’t as if I’d been expecting him to shriek ‘me too!’ and throw his arms around me, but a bit of an indication either way would have been welcome. He hadn’t jumped off the mattress in disgust, at least.

‘So, I’ve not seen you around the Poly before?’ I ventured.

‘No, I’m over at Holloway Road,’ he confirmed. ‘And only part-time.’

‘Oh, right. What do you do in real life then?’

‘I work for the GLC. Grants department. They’re putting me through an accountancy course.’

Not exactly the sexiest option, but not enough to put me off him. And he got extra points for working for Ken Livingstone’s council. Ken was a bit of a hero as far as I was concerned: one of the only politicians who was willing to stand up for gay rights, and put his money – or at least the GLC’s money – where his mouth was, and he took a hell of a lot of stick for it. Just this week I’d been reading in Capital Gay about a big grant to Gay Switchboard, where some friends of mine volunteered. For all I knew, Liam had been the one doing the paperwork. I hoped so. It had already been written up in the other papers as yet another example of Ken’s support for the ‘Loony Left’: if that was the case, I was as proud to be a loony as I was to be a gay.

‘Cool place to work,’ I enthused.

He pulled a face. ‘Ach, it pays the bills.’

‘Literally,’ we both found ourselves saying together, and grinning at the weak joke.

‘So do you think you’ll manage to keep your job?’ I asked. Livingstone had been doing such a good job of opposing the government – a far better one than the wet blanket that was the national Labour party – that Mrs Thatcher had announced her intention to wipe out the GLC completely: she’d already followed Hitler’s example by cancelling next year’s elections, and was pushing through plans to get rid of the whole thing in a couple of years’ time. Maybe because they were scared she was going to go on to do the same thing to them, a few Tory MPs had found their spines and rebelled against the legislation: it was currently looking as if she might not be able to get it through after all.

‘Who knows?’ Liam let out a frustrated sigh. ‘We’re trying to get grants through as quickly as we can, just in case we turn up one morning and find the locks have been changed.’

‘D’you see much of him? Ken?’

‘Not so much. He comes to the Christmas party. But he’s off round the country a lot these days, campaigning against the abolition. It’s his sidekick, John McDonnell, who does a lot of the day-to-day stuff. He’s my boss – well, my boss’s boss. He’s a sound guy too; knows the score.’

I was impressed. Liam couldn’t be more than twenty-five or twenty-six, but he talked like a proper grown-up. Whereas I was pushing twenty-nine – practically a pensioner in gay years – and still a student. I’d finished my degree the year before (and got a first, thank you very much) – already a so-called ‘mature’ student with six years on most of my contemporaries. But I had taken one look at an unemployment figure north of three million and decided academia was probably the place to stick around for as long as possible. My course tutor had been only too delighted at the prospect of having me back. He pointed me in the direction of a couple of bursary funds that might be happy to take over Berkshire County Council’s job of paying me to do my favourite thing in the world and read books all day. And before I knew it I had another entire year of study stretching before me. I figured even Sir Keith Joseph couldn’t manage to abolish higher education in that time.

‘What about you?’ asked Liam. ‘What are you studying?’

‘Oh, English literature.’ Surrounded by people studying things like polymer science and social work, I always felt a bit apologetic when I talk about my own course. ‘Well, they call it English, but it covers a lot of Commonwealth authors too. And Irish ones,’ I added as an afterthought, before suddenly panicking that he was going to ask me which ones. I’d made it about a hundred pages into Ulysses before giving up on the grounds that nothing had actually happened yet. And I still refuse to believe anyone has ever actually read Finnegan’s Wake.

Instead, he decided to ask me something just as awkward. ‘So who are you studying at the moment?’

‘Shakespeare,’ I said lamely, adding ‘the problem plays,’ in the hope that made it better.

His forehead furrowed. ‘And which ones are those when they’re at home?’

‘All’s Well that Ends Well, Measure for Measure and Troilus and Cressida.’

‘Troilus and who?’

‘Cressida. It’s about the Trojan War.’

He smirked. ‘No. You sure you’re not making these up? I’ve not heard of any of them.’

‘I wish I was!’ I’d chosen the topic for my postgrad diploma the previous term, and been slightly regretting it ever since.

‘Hamlet,’ Liam continued, his smile widening. ‘Now that’s a Shakespeare play, I’m sure of it. Macbeth. Julius Caesar. Shame they don’t let us have a pen and paper in here, you could be writing these down.’

I gave him a mock exasperated look. ‘Ha ha. Very funny. If you’re running short, there’s about fifteen Henry-the-something-or-others. Do I get to make jokes about your course too?’

He pushed himself back against the cell wall. ‘Ach, it’s accountancy; there’s nothing funny to say about it, believe me. How’s your back now? That was a powerful knock you took.’

I raised my hand up to my left shoulder. ‘Bit sore. Having my arms cuffed behind me didn’t help much.’ I tried to rotate my upper arm again, and winced as a sharp pain went through me.

‘You all right?’ Liam was looking at me, concerned.

‘Yeah. Yeah. I’ve had worse.’ I’d once had a policeman grind my face into the table in an interview room, and he was being quite friendly at the time, for him. ‘What about you? It looked like you got a bit of the same treatment.’

‘It’s no bother. Back home I’d have been risking a plastic bullet in the head.’

I laughed slightly too loudly at this, partly out of shock and partly to demonstrate how unshocked I was by it, and then winced again as another spasm went through my shoulder.

‘Here; turn around.’ Liam sketched a spiral in the air, indicating I should turn my back to him. ‘Go on, I’m not going to hurt you!’

I shifted around on the bed to face the bare breeze blocks, the thin mattress twisting beneath me, its rubber letting out a protesting squeak. I’d had to hand in my denim jacket at the desk, along with my haversack, everything in my pockets and the laces from my Dr Martens, and all I had on my top half was a thin cap-sleeve t-shirt. I felt suddenly self-conscious about my arms, and how much less muscular than his they were.

And then his hands spread across my shoulder blades and started to massage me, and I forgot about everything except for how good they felt.

‘How’s that?’ he asked me after a few electric seconds.

I made a noise that was somewhere between a gulp and a purr, and then, embarrassed, coughed a ‘really good, thanks.’ But even as I got the words out his fingertips stroked their way up all the way to my bare neck, and I wouldn’t have trusted myself to speak at all any more.

And in that moment I made a decision: that whether Liam Delaney was or wasn’t gay, at the very first opportunity that presented itself, I was not going to have sex with him.

FOUR

It was a new policy I was trying out. For too long I’d been jumping into bed, and quite often not even waiting for a bed to be available, with any and every man I fancied. Which had made for a great deal of fun, and I hardly regretted a second of it, but the harsh fact was, it wasn’t getting me anywhere: like I say, I’m nearly twenty-nine.

I have tried. There was one guy I was sort of seeing for a while in the second year – Simon, star of the Drama Society, whose production of The Knight of the Burning Pestle I’d stage-managed during a brief and slightly half-hearted attempt to get myself more involved in student life. He was actually a really nice bloke, very good-looking and obviously up for something long-term, but fond of him as I was, I still found myself making excuses to get away and spend the night in my own bed. I told myself the same things I told him – that his hall of residence was too noisy and the single mattress not much more comfortable than the one I was sitting on right now – but I think he probably worked out before I did that my choosing to regularly schlep half-way across London in the early hours rather than, say, ever invite him to my place, meant we were never going to be love’s young dream.

Well, so what? I had figured, once he’d made his little scene at the closing-night party and pointedly got off with the girl playing Luce in front of me. It wasn’t like I was short of offers. A surprising number of students turned out to be heteroflexible after a few pints in the union bar, and those who weren’t could sometimes be persuaded it was their political duty to be. And when I got sick of them there was always The Bell and The Fallen Angel, where I spent much of my weekends and student grant, and they saw plenty of new faces arriving every year who didn’t know me from the old days.

But the feeling of not getting any younger had been hammered home since I had returned as a postgrad the previous September. All right, I’d always been a good few years senior to everyone else on my course, but I was lucky enough not to look it – the boyish looks that had kept my head above water on the Dilly seemed to be sticking around, at least for the moment. Having missed out on so much normal life first time around, I’d been quite happy to go with the flow and not act my age for a while. But when I came back to London that autumn expecting business as usual I found everything felt really different. While the three years of my BA, ranging over the whole of English literature from Chaucer right through to DH Lawrence, had tallied nicely with my unspoken life’s ambition of reading All The Books, it turned out that a PgDip was more about over-reading a very small number of books in particular, and that was a lot less fun.

An even bigger culture shock came at the first meeting of the Poly’s tiny Gay and Lesbian Society of the new year, when I’d sat listening to a nineteen-year-old first year enthusing at length about how Boy George staying at Number One for six weeks despite wearing a dress on Top of the Pops meant our struggle was all but over. I’d lost my rag and had a little rant about how the only way Boy George had made himself acceptable to the public was to pretend he’d rather have a cup of tea than have sex, and how, when the establishment was presented with gay men who looked like they actually enjoyed shagging – like Marc Almond – they still ran a mile. Just a few weeks later I thought my point was rather well demonstrated when the BBC banned Frankie Goes to Hollywood’s ‘Relax’, but by then the moment had long passed. At the time, the poor kid just looked so frightened I thought he was going to cry. Then I looked round at the other shocked faces and realised that, lesbians aside, he was the only person in the room I hadn’t already had sex with, and suddenly felt very old indeed.

So – time for a change. I was on the hunt for someone I could have an actual relationship with, or at least try out the concept for size. Not necessarily the full golden retriever and house in the suburbs – or whatever the homosexual equivalent might be: poodle and penthouse? – but something that lasted longer than a few weeks, a few days, or just a couple of messy minutes. And the last thing I wanted to do with someone with as much potential as Liam was spoil things by shagging him too early.

OK, if we want to get psychological about it, even I had realised it was probably to do with the years I’d spent working the Dilly. Having sex for money doesn’t exactly endear you to the men who are paying: you want to get the job done and be out of there as quick as possible, and if that’s what you get used to at an early age it kind of sticks. It was a very long time since I got out of the game – over eight years before – and my sex life had been strictly for my own pleasure ever since, give or take a couple of pity fucks I liked to class as charity work, but nevertheless I’d found it hard to kick the habit. Even with guys I really fancied, I found myself thinking about how best to extract myself from the situation before the tissues were even dry. If I’m totally honest – and this is getting way, way further into lie-on-the-couch-and-tell-me-about-your-childhood territory than I like – I think I lost not just interest in, but respect for, men as soon as they’d had sex with me. Plus there were other things to think about by then: like everyone else, I’d watched the documentary the previous year about the new disease that was spreading like wildfire through gay men in San Francisco and New York. The footage of men reduced to living skeletons, their skin horribly disfigured, parasites eating away at their guts, had stuck with me. I knew there had only been a handful of cases over here so far – Capital Gay kept a running total in a little column in the back pages – but it had been enough to do what I previously thought was impossible and make me moderate my sexual behaviour: I had started point-blank refusing to have sex with any Americans. If it had been any other country I’d have called myself a racist.

Obviously that wasn’t going to be a risk with Liam. But I wasn’t about to screw things up with him. He was way too good to waste on a quick bit of wham, bam, thank you man. If I was going to do him, I was going to do him properly.

And, please God, it had to happen. I closed my eyes, and all I could see were those big brown eyes, and those big full lips – so kissable. The hard prison bed beneath us and the close walls of the cell flew away under the touch of his fingertips all over my back and shoulders. I was practically melting. It was taking every ounce of self-control I had not to just lean back into him and whisper ‘take me right now’.

A line from the play I’m doing my extended essay on, Measure for Measure, kept running through my head as his hands roamed across me: ‘Ever till now/When men were fond, I smiled, and wondered how.’ Admittedly it comes from the mouth of Angelo, a self-loathing puritan who has just decided he wants to rape a nun, and he ends up shagging someone else by mistake and then begging to be put to death, but I refused to take that as a bad omen. Things tend to work out like that in Shakespeare slightly more often than they do than in real life.

Just as I thought I wouldn’t be able to hold myself back, or rather forward, for a second longer, a loud clunk echoed through the cell and we both pulled ourselves apart like we’d been scalded as the door began to swing open. One of the custody officers, the one that had signed Liam in, was standing in the doorway. ‘C’mon, you two. You’re free to go,’ he told us.

‘What, just like that?’ asked Liam, jumping up from the bed. I took a bit longer to stand up. There were certain adjustments I had to make first.

‘Yep,’ confirmed the sergeant. ‘You’re not being charged with anything.’

‘Too right we’re not!’ snapped Liam, suddenly ebullient. ‘Because the only ones doing any assaulting were youse lot. I’ve a good mind to –’

‘Leave it, Liam,’ I said quietly, giving a warning tug to the back of his t-shirt. If we were getting a free pass, there was no point in fucking things up now. Sure, it wasn’t fair for us to have been locked up at all, but then, whoever said life was?

Thankfully, his protests subsided into no more than a low growl as he stalked past the sergeant and out of the cell. I gave him an apologetic, but hardly heartfelt, smile as I followed. ‘Are you letting everyone else go, too?’

‘Oh no.’ The sergeant’s grey moustache and bunch of keys put me in mind of Mr McKay in Porridge. ‘We’ve got seven of your mates being charged with obstruction, and defying a court injunction. You two, fortunately for you, were on the wrong side of the road at the time, and we’ve got witnesses to say so, so you get to piss off.’ He set off up the corridor back towards the custody desk.