Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Eye Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

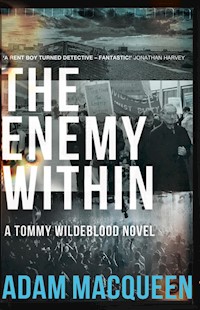

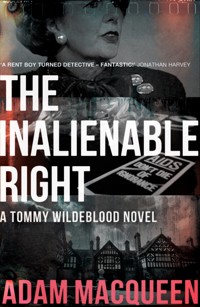

- Serie: Tommy Wildblood

- Sprache: Englisch

In the age of AIDS and Section 28: a secret that could change political history It is 1987, and Tommy Wildeblood has put his days as a Piccadilly Circus rent-boy long behind him. Slightly to his own surprise, he is now a rookie teacher at a South London comprehensive. But when Margaret Thatcher's government launches a chilling attack on the 'promotion' of homosexuality in a new law known as Section 28, Tommy can't stay silent – especially when he realises he may have information about one of Thatcher's key lieutenants that could change the political situation completely. Forming an uneasy alliance with a sharp-elbowed tabloid journalist, and delving deep back into his past on the 'Dilly', he puts everything on the line – for both himself and his old friends – in a desperate bid to expose the truth. With his trademark blend of historical research and 'what if' fiction, Adam Macqueen captures the spirit of a frightening age in another spellbinding case that lifts the lid on the Eighties political establishment's murkiest secrets.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 565

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2025

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

ADAM MACQUEEN is a senior journalist on Private Eye and co-presents its podcast, Page 94. His non-fiction books include the bestselling history of the magazine, and political miscellanies The Prime Minister’s Ironing Board and The Lies of the Land: An Honest History of Political Deceit. He has also been on the editorial team of Popbitch and The Big Issue. His first novel Beneath the Streets, in which he introduced the character of Tommy Wildeblood, was longlisted for the Polari Prize.

Praise for Beneath the Streets

‘A wonderfully evocative walk on the wild side of 1970s London. Darkly comic and deeply moving. A breathtaking, heartbreaking thriller’

Jake Arnott

‘Ticks all the boxes for me. Gay history. Jeremy Thorpe. And a rent boy turned detective called Tommy Wildeblood. Fantastic’

Jonathan Harvey

‘Adam Macqueen’s gripping debut novel is based on a provocative counterfactual question... He depicts his grim milieu engagingly – and this very English scandal has wit and invention to spare’

The Observer

‘You think you know how mental the 1970s were? This book will remind you that they were even more insane than that: the prime minister’s personal doctor seriously offered to poison one of his aides. Any TV adaptation would probably need 10 percent fewer blowjobs’

Helen Lewis

‘Adam Macqueen’s excellent debut thriller takes us back to 1976, a time of very British scandals. Former rent boy Tom Wildeblood is a thoroughly likeable hero, and the seedy allure of the period is convincingly rendered, while the plot skilfully mixes fact with fiction’

Mail on Sunday

‘After I finished writing A Very English Scandal, I took a solemn vow – that I would rather spit-roast my own offspring than read anything else about the Jeremy Thorpe Affair. Seldom have I gone back on my word with more pleasure. As boldly conceived as it is vividly realised, Beneath the Streets is a delight’

John Preston, The Critic

‘A thrilling and brilliantly imaginative novel. It takes you into the secret world of Soho in the 1970s. But then suddenly it opens another door into the hidden world of violence and corruption that still lies underneath the England we know today’

Adam Curtis

‘A gripping thriller, interwoven with a really important thread about the condition of being gay in the 1970s’

Harriett Gilbert, A Good Read, BBC Radio 4

‘What if Jeremy Thorpe had succeeded in murdering Norman Scott? That’s the gripping premise behind this smart story of corruption, murder and establishment cover-up’

iPaper, 40 best books of the year

‘Really well done. The detail and the authenticity is all there: London as a really scary, edgy, ugly place. The atmosphere is brilliant... I also read it with my computer by my side because I was constantly looking up the real-life figures and I was constantly shocked and amazed by how much of this is true’

David Nicholls

‘A f***ing fantastic read. A gripping what-if thriller, packed with vivid period detail and page-turning twists. To find myself actually making an appearance in the final chapter was just cream on the cake’

Tom Robinson

‘A page-turning mystery, skilfully plotted and filled with tension, Beneath the Streets lifts the lid on 1970s subculture to spine-tingling effect’

Paul Burston

‘Agripping and occasionally hilarious depiction of what, up to this year at least, must have been the craziest period of modern British politics. The twist, on literally the last page, is superb. While some 1970s scandals were played out beneath the streets, some were hiding in very plain sight’

Law Society Gazette

Praise for The Enemy Within

‘Rent boys. Revolutionary communists. Frankie Goes to Hollywood. And a plot to blow up Mrs Thatcher’

Popbitch

‘An accomplished and gripping continuation of Wildeblood’s adventures [in] a grim 1980s bedevilled by Aids, Thatcherism and IRA bombings. Cameos by everyone from Jeremy Corbyn to Derek Jarman add texture and wit’

The Observer

‘Brilliant. Beautifully drawn. A superb final twist’

Boyz

‘This rollercoaster queer thriller is a cracking read: a complex love story, an adventure racked with radical threat and emotional trauma, an on-point political history of 80s social anxieties and protests, and a stonking good who-dunnit and who-dunn-what’

Scene Magazine

Published in 2025

by Lightning

Imprint of Eye Books Ltd

29A Barrow Street

Much Wenlock

Shropshire

TF13 6EN

www.eye-books.com

ISBN: 9781785634055

Copyright © Adam Macqueen 2025

Cover by Ifan Bates

The moral right of the author has been asserted. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

In memory of Peter Macqueen, who never fully recovered from the time he spent in a children’s home

Many of the people in these pages, from protesters to parliamentarians, share their names and certain other biographical details with real people.

That is all they share.What follows is a work of fiction.

Contents

part one

one

two

three

four

five

six

seven

part two

one

two

three

four

FIve

SIX

seven

eight

nine

ten

eleven

twelve

Thirteen

fourteen

fifteen

sixteen

part three

one

Two

Three

four

five

six

seven

eight

nine

Ten

eleven

Twelve

Thirteen

fourteen

fifteen

sixteen

seventeen

eighteen

nineteen

twenty

twenty-one

twenty-two

twenty-three

part four

one

two

three

four

five

six

seven

eight

nine

Afterword

Also by Adam Macqueen

part one

‘In the inner cities, where youngsters must have a decent education if they are to have a better future, that opportunity is all too often snatched from them by hard-left education authorities and extremist teachers…

Children who need to be able to express themselves in clear English are being taught political slogans. Children who need to be taught to respect traditional moral values are being taught that they have an inalienable right to be gay. And children who need encouragement – and children do so much need encouragement – so many children – they are being taught that our society offers them no future.

All of those children are being cheated of a sound start in life – yes, cheated’

Margaret Thatcher,

Speech to Conservative Party Conference, 9 October 1987

one

The coffin wobbled as it went down into the ground, the nervous bearers failing to find a mutual rhythm as they let the cords play out, hand over hand. There was a nasty moment when one of the corners at the head end dipped several inches below the others, and a muted gasp went up from the family but was hastily swallowed back, embarrassment as ever the most dominant of English emotions, even amid the stew of shock and grief and anger that was swirling around this small country graveyard.

The chief undertaker, in position at the head of the grave, took an urgent step forward, but his hands did not even need to leave the brim of the black top hat he was gripping: a quiet word of instruction was enough to restore decorum around the graveside. The bearer responsible, an older woman, one of two aunts who had been recruited for the job at the last minute, was bright scarlet, her forehead sheened with perspiration, but she managed to complete her duties without any further disaster. As she and her companions laid down the cords on the freshly cut turf and stepped back from the grave’s edge, the young man to her left, the only one who had looked definitely physically fit for the task they had just completed, stepped over and put a comforting arm around her shoulder. She dissolved into his chest in a flood of tears.

‘There’s some good strong men over here could have done the job for you,’ muttered a voice to Ryan’s right.

‘Alright, leave it, lads,’ Ryan murmured as a ripple of disgruntled agreement ran through the group. ‘We’re here, at least.’ His soft Belfast accent was somehow both soothing and authoritative enough to keep a lid on the fractious situation that was developing in this corner of the graveyard. It must be a policeman thing. An ex-policeman thing.

The group was too far away to hear the words of the vicar as he stepped forward, bible in hand, so Olly provided his own version: ‘Ashes to ashes, funk to funky.’

‘If you tell us again how you could have been in that video if you hadn’t overslept, I will actually shove you into that grave myself,’ muttered Gary, and the whole group bit their lips, clenched their fists and tried desperately not to dissolve into the most inappropriate fit of giggles ever. It was a lovely moment. It felt like what the deceased would have wanted.

As the formalities ended and the group around the grave broke away from their positions to reform into a ragged queue beside the neat pile of earth left out for scattering purposes, our own group also shifted from our regimented stances. Ryan took the opportunity to slip an arm around me and give the small of my back a comforting rub. ‘How are you doing, Tommy?’

‘I’m OK,’ I told him, my voice sounding steadier than I had expected. ‘Going to too many of these; that’s all.’

‘Tell me about it.’ The funerals were getting closer together now. Clarrie, the first of my friends to succumb to Aids, had been dead three years now. Ivan, who I’d only really got close to at the very end of his life, died the following year, not that long after news came that his partner Paolo had passed away in Italy, his furious family keeping the pair of them apart right to the end. Three other friends from the Icebreakers group where I had met Ivan were gone, including Mark Ashton, the man who had seemed the most radiantly alive of all of us. We’d buried him last February. Daniel, the partner of Dougie who was here with us, in April. And now Marcus. And it was still only October.

I snuck a glance at Dougie to see how he was bearing up. He was pale and leaning heavily on his walking stick, but our friends Gary and Brian had stationed themselves on either side of him for support, both emotional and, if necessary, physical. He caught me looking and gave me a nod and his best attempt at a reassuring smile, but it came out more like a grimace. The long dangling earring he wore in his right ear only served to accentuate the hollowness of his cheeks and the pale paperiness of his skin.

He had already been diagnosed with Aids-Related Complex when we had been saying goodbye to Daniel, the love of his life, and he’d been informed he’d progressed to the full-blown disease not long afterwards. He’d told us this morning he was fighting a fungal infection in his lungs, and he’d started to lose the sight in his right eye, thanks to something called cytomegalovirus, a suitably monstrous name. It was impossible to say how long he might have left. And still he was raging against the dying of the light.

A loud, attention-demanding ahem floated over from beside the graveside. Most of the ceremony might have been inaudible from where we were standing, but the young pallbearer, Marcus’s older brother, was clearly determined we should hear this bit.

‘My mother and father have asked me to say that there will be drinks and refreshments back at the church hall, for friends of the family only.’ Just in case we didn’t get this, he fired a furious glance in the direction of our group.

‘Oh, and they’d made us so welcome up until now,’ commented Gary, in a voice that was also meant to be heard.

‘Alright,’ said his partner Brian, reaching out an admonishing hand to his chest. ‘Leave it.’

‘Ach,’ said Ryan, ever the peacemaker. ‘At least we made it in to the service. That’s more than we sometimes manage.’

A man we knew from our local gay bar had been telling us just the other weekend about how he and a group of other gay men had been physically barred from going in to a friend’s funeral. The family had actually hired bouncers to stand outside the crematorium.

‘Arseholes,’ Gary muttered, but he turned away and, taking Dougie’s arm, started to lead him towards a bench in the shadow of a big yew tree while we waited for the other mourners to disperse.

‘We can find a pub or something, can’t we?’ I suggested to the rest of the group. ‘Be good to toast Marcus’s memory and have a catch-up while we’ve got the chance.’ I looked at Olly, who, absurdly, was wearing dark glasses despite the grey autumn sky. ‘That’s if our celebrity friend can spare the time from his busy schedule?’

‘Oh, piss off, Tommy,’ he said affectionately. ‘I’m fine, I’m not due on set till tomorrow.’

Olly’s got a part in this new hospital thing on the BBC. It’s filmed in Bristol, so this – Marcus’s funeral in his home village in Hampshire – was the first time any of us had seen him in ages. ‘How’s it going, anyway?’

‘It’s good. Hard work. But they’ve signed me up for another series, so I know I’ve got a regular wage coming in for the first time in God knows how long. And they’re a nice bunch. We have fun. D’you watch it?’

I shook my head. ‘Saturday nights, you know. Better things to do.’

He looked momentarily crestfallen before Ryan chipped in to reassure him. ‘He’s lying. We never miss an episode.’ That wasn’t entirely true, either, but it was Ryan all over to pretend it was, and it set Olly beaming. ‘Tell us, are they setting you up to have an affair with that young nurse, the one with the red hair?’

Olly shook his head gleefully. ‘I’m not allowed to tell you. State secrets. She’s lovely though, Cathy, the actress who plays her. We have a right laugh together.’

When he was in his twenties and even prettier than he was now, Olly used to boast that he could seduce any man, gay or straight, within twenty minutes of meeting them. His specialism back in our days on the Dilly was what he called the double dip: him and a friend both doing oral sex on a client at the same time. I’d been the friend on many of those occasions. ‘Is it not weird?’ I asked him. ‘Doing love scenes with women?’

‘It’s called acting, dear,’ he camped, then added in an undertone: ‘Anyway, don’t tell me you don’t know how to put a show on for someone you don’t fancy. Present company excepted, of course.’

I conceded the point with a grimace. ‘Speaking of which…you seen Lee recently? I wasn’t exactly expecting to see him here, but…’

‘Why not?’ Ryan asked.

I sometimes forgot he was a late entrant to the gang. Most of us had known each other from way back in our days on the Dilly. ‘He and Marcus never got on,’ I explained. ‘Personality clash.’

‘Really?’ Ryan looked surprised. He liked Lee. But then, everyone liked Lee. He was a born charmer. Most of the time.

I turned back to Olly. ‘But is he OK, d’you know? We haven’t seen him in ages.’

Olly shrugged. ‘I’ve not heard from him in a while. But you know what he’s like; he’s flaky as fuck.’

Lee had continued ducking and diving right through his twenties: none of us were ever quite sure what he was up to.

‘He’ll turn up, he always does. Probably at the least convenient moment for everyone.’ It wasn’t said unaffectionately, but I had the impression he was hiding his true feelings behind those sunglasses as he looked around the almost empty graveyard and changed the subject. ‘Looks like the coast’s clearing. What’s our plan?’

‘We passed a pub on the way in to the village that didn’t look too terrifying,’ suggested Brian. ‘D’you want to follow us? We’ll take Dougie.’

‘You sure we’re not going to get driven out by yokels with pitchforks?’ asked Olly, only half joking.

‘I’m not guaranteeing anything,’ said Brian. ‘But there’s strength in numbers.’ He and Gary live down in Brighton where they run their own antiques business: it’s just about the gayest place in Britain, although even that doesn’t guarantee anyone’s safety these days.

‘You know we’ve got our own local gay club these days?’ I told Brian as we waited for Dougie to hobble back from the bench with Gary and join us. ‘In Forest Hill?’

Ryan and I went south of the river when we moved in together a couple of years ago. He needed to get far away from anyone in North London who might recognise him from his former life. We’d briefly considered Brixton, which at least has the advantage of being on the Tube, but there were people round there I wasn’t desperate to run into again. What can I say? We both brought our fair share of baggage to the relationship.

‘Really?’

‘Yeah, Frolic it’s called; terrible name. Don’t know how long it’s going to last, though. It got raided last month. Police in the full gear, rubber gloves on, saying there had been complaints from the neighbours. They took away all the membership books, all the cash in the till. Then they followed the landlord, Philippe, when he went out in his car the next day and stopped him. Guess what for?’

‘Go on.’

‘“Driving a vehicle in a potentially dangerous condition.” They said his car had rust on it.’

‘You’re joking!’

I shook my head. ‘I know. I’ve seen his car: it’s in a way better state than our old banger. Now he’s got police cars sitting outside every night the place is open. Just sat there watching the punters go in and out. We give them a wave every time we go by.’

Ryan and I had been going to Frolic on principle every weekend since the raid. We didn’t even like the place that much.

‘They’ve told Philippe people like us belong in the West End, not the suburbs, and they’re not going to stop till they’ve sent us back there.’

‘Christ,’ said Brian with feeling as Dougie and Gary joined us and we started off after the others towards the church gate. ‘You and Ryan should move down to Brighton. Honestly, life’s so much easier down there; you’d love it.’

I pulled a face. The place held some dodgy memories for both of us. And besides, why should we have to corral ourselves into a gay ghetto just to be treated like decent human beings? ‘Maybe one day. Anyway, the school where I’m working is a fifteen-minute bus ride away. That’s enough of a commute for me, thanks!’

‘How’s the job going, Tommy?’ asked Dougie.

‘Good! Good. Well, I think so. I’ve made it to half-term at least.’

‘I still can’t quite picture you as a teacher,’ said Brian.

‘Course you can. He’s always been dead clever.’ Gary is unfailingly, touchingly loyal, although we both knew it wasn’t my brains, but my background his boyfriend was referring to. ‘D’you remember we used to call him the Bookworm back in the day?’

Brian chuckled. ‘I’d forgotten that. No, I think it’s brilliant, don’t get me wrong. I’m just… it’s not what I’d have predicted, that’s all.’

‘You and me both,’ I told him.

I’d only signed on for teacher training because I could get a grant for it and put off having to get a job for another couple of years. I’d been shocked by how much I actually enjoyed the course, especially the practical side of it. If you’d asked me five years ago how I’d feel standing in front of a class full of teenagers, I’d have told you I couldn’t think of anything more terrifying. That wouldn’t necessarily have been wrong: there were definite moments of terror involved. But it turned out that when you knew what you were talking about (and I did: the passion for books that earned me my own teenage nickname has never left me), and you were able, like Olly, to fake like you knew what you were doing, it somehow all worked out.

I’d even started adding little innovations of my own to the syllabus: I chose a word of the day and put it up on the blackboard each morning, then got each class to discuss what they thought it meant: things like escutcheon,rambunctious or horripilation that everyone from the first years to the sixth form could have a go at guessing. Some of the ideas they came up with were way more interesting and imaginative than the reality, and those five minutes at the start of the lesson often ended up teaching them way more about language than plodding through Macbeth or I Am David. Lych-gate, I thought, as we passed through one of those and out onto the lane where the cars were parked. That would be good to add to the list.

They would probably think it had something to do with lynch mobs. Quite a lot of those about these days.

two

It was only a short drive to the pub, which was your bog-standard horse brasses and hunting prints sort of place, fruit machine flashing away in the corner. It was, however, obviously long enough for Gary to have had a word with Brian because as we left him and Olly and Ryan to get the drinks in, and got Dougie settled at a corner table as far out of earshot from the t-shirted occupants of the barstools as we could, the older man made a point of saying, ‘I didn’t mean anything by what I said back there, you know. I’m sure you’ll make a really good teacher.’

‘I don’t know about that.’

‘Of course you will. No, I just meant…you know, with what you used to do.’

This was some beam-in-your-own-eye stuff if ever there was. Brian still has a hang-up about how he met Gary, who worked the meat rack on the Dilly alongside me and Olly and Marcus back in the day. He doesn’t like to remember that he paid for his boyfriend’s company for at least the first year of their acquaintance. But me, I’m supremely unbothered by my past.

At least up to a point. ‘Yeah, well, it was all a long time ago. And obviously, I’m not publicising any of that,’ I admitted.

Dougie arched an eyebrow. ‘Any of it?’

‘No,’ I hastened to explain before he could deliver one of his lectures. ‘I mean, I’m not…in the closet or anything.’

I wasn’t exactly advertising my gayness at work. There had been surveys saying more than half the public thought homosexuals should never be employed as teachers, so I was hardly going to flag it up in my interview with the head. But Denise, the head of English, had known about Ryan for a couple of weeks now.

She was very nice about it – she’s got CND and Reclaim the Night badges on her duffel coat, so I’d been pretty sure she’d be OK with it before I chose to drop his existence into conversation. She kept saying the pair of us must come round for dinner with her and her partner, a (male) university lecturer, some time. Although she did seem to think she was the first person ever to ask which of us was Colin and which was Barry, which was getting very irritating. We don’t even watch EastEnders.

I felt like they were still looking at me expectantly. ‘I’m just not – you know. The past’s the past.’ I wasn’t even Tommy at school: I’d reverted to my birth name, Alex, or Mr Hargreaves to the pupils. Alex Hargreaves felt a lot more grown-up, professional. It wasn’t that I’d left Tommy Wildeblood behind, exactly, just…tidied him away a bit. Definitely not into a closet, let’s be totally clear about that.

Olly arrived with a pint of Castlemaine XXXX for each of us, and I looked to him for backup. You’ve never seen anyone straighten up so quickly as he did since he got his big break on TV. ‘I’m just not advertising it; that’s all. You know what people are like about teachers. Think of the children! I mean, you heard Mrs Thatcher last week!’

‘Yeah, what the fuck was that all about?’ spluttered Olly.

The prime minister had stood up in front of the Conservative Party conference and basically accused teachers of corrupting the young, putting ideas in their head that they had what she called ‘the inalienable right to be gay’, as if there was anything we, they, or anyone else could do about it if they were or weren’t. I was still seething about it. So, predictably, was Dougie and eventually, once it had been explained to him, Gary, whose awareness of politics barely stretched beyond knowing that Mrs Thatcher was still the prime minister. ‘What does “inalienable” mean, anyway?’ he demanded. ‘E. fucking T.?’

‘Exactly that!’ I said hotly. ‘That’s what she wants to do to us. Alienate us. She doesn’t want to just outlaw being gay – we’ve been there before, done that, got the t-shirt. She wants to make us inhuman. Like we don’t even have the right to exist here.’ I was so fired up, I had temporarily forgotten that the men at the bar might overhear us, but I couldn’t help myself. Thatcher’s determination not just to stop us doing what we do in bed, but to take away our very right to be, made her just as cruel and evil as the disease that was already doing the same job so very effectively.

‘She can’t actually do anything, though. Can she?’ asked Olly.

‘Of course she can! It’s already started! We had instructions from the Department of Education last month – they’ve gone to every school in Britain – telling us exactly what can and can’t be taught in sex education classes. And guess what’s the big thing they’re worried about?’

I knew the wording off by heart, I’d gone over my copy of the guidelines so many times. ‘You’re not allowed to say anything that “advocates homosexual behaviour, which presents it as the norm or which encourages homosexual experimentation by pupils”. As if we’re running a bloody recruitment campaign! There’s literally a bit – and this is signed off personally by the education secretary, mind – that points out teachers would be committing a criminal offence if we “encourage or procure homosexual acts by pupils who are under the age of consent”.Procure. Like we’re fucking child molesters.’

‘That’s disgusting,’ said Brian. There was a murmur of consent around the table. Even Ryan, who’d heard this rant plenty of times before, joined in.

‘What do your colleagues think about it?’ Dougie asked.

‘Oh, everyone’s furious about it,’ I assured him. That might not actually have been true – a lot of the staff had taken their photocopies from the head without comment – but those who did object made up for it with the ferocity of their reactions.

‘I ought to sue Kenneth Baker for calling me a bloody pimp,’ the head of science, Dennis, had said in front of the whole staffroom, to several ‘hear hears’. I’d found that comforting: I know for a fact Dennis is married with five kids because I teach several of them, and they all come filing out of his Volvo in the staff car park every morning like the Von Trapps.

‘Well done to you all for standing up against it,’ said Dougie, holding up his glass of orange juice towards me. My glass was almost empty, but I clinked it against his anyway, feeling slightly guilty. In the event I’d done little more than join in the hear-hearing before stashing the handout in my work bag so I could rant about it to Ryan later.

By contrast, Dougie’s reaction to being told recently that he still he didn’t qualify for AZT, the only Aids medication that might help him, had been to chain himself to the front of the offices of the drug firm that made it and call the papers. He’d got his picture on the front of the Independent.

‘Would you come and talk to OLGA about all this?’ he asked.

I sniffed uncertainly. ‘Who’s Olga?’

‘It’s a new group I’m involved with, the Organisation for Lesbian and Gay Action. Very new, actually; we’ve only set it up this month. It’s a bunch of us who got sick of all the shilly-shallying in the Lesbian and Gay Rights Campaign. Going to be more focused on direct action than talk, talk, talk.’

I could feel my hackles rising. I’d more than served my time when it came to gay groups. And politics in general, for that matter. ‘I don’t think so. Sorry, Dougie. That’s not really my thing these days.’ Ryan had taken me out of that world a few years back and I didn’t feel much inclination to go back to it.

‘But you’re passionate about this; that’s obvious,’ Dougie pointed out with an irritating smile. ‘Maybe we could help you to do something about it?’

‘I… I really don’t think so, sorry. I’m not in the closet, I’m really not’ – it was infuriating, the way I felt the need to justify myself to Dougie – ‘but I don’t want to be some kind of…poster boy either. Sorry. I just can’t. Not at the moment. Not until I’m through my probation year, at least.’

Dougie said nothing, but just shook his head, his eyebrows raised. I felt a wave of embarrassed anger – or maybe it was guilt – wash over me, bringing a redness to my cheeks. But honestly, what would be the point? Because as much as I admired people like Dougie, and everything they did, from where I was standing, one thing was very obvious. The baddies had already won. If there had ever been any hope, then it had vanished at the election in the summer, when, despite everything she had been responsible for over the past eight years, Maggie had unbelievably been voted back in with another landslide. Her third term, out of God knows how many there were going to be. The horrible truth was that the reason she was acting like such a thug now was because she knew she had most of the country behind her, egging her on to greater and greater brutality. And even thinking about that made me want to curl up into a ball and cry. Or maybe emigrate. Except that I couldn’t think of anywhere else in the world that Ryan and I would be welcome.

three

‘Hello you two!’

Mum practically erupted out of the front door, clearly delighted to see us. She must have been watching from the lounge window. We hadn’t visited for a while, and since Reading was on the way home, a night with my parents meant we could be discharged of our duties until at least Christmas.

She pulled me into her arms on the doorstep, gave me a brief peck on both cheeks, and then shifted me on swiftly so she could give the exact same treatment to Ryan. The pair of them got on great. Slightly too well, sometimes: I liked to wind both of them up by telling them he’s the son she never had.

Her enthusiasm for my boyfriend makes up for my dad’s wariness. He doesn’t exactly dislike Ryan, I don’t think, but he’s always found it hard to get past his general distaste for the concept of him. Mind you, he’s not exactly over-affectionate with me either: when we got through to the hallway Ryan and I both got the same slightly limp handshake and ‘good to see you’. He did at least get up from his chair and come to the lounge door to deliver it, and he’d turned the telly down too, which for him counts as an effusive display of emotion. His hair’s almost completely grey these days. I think Mum’s probably is too, but she does a very decent home dye job.

‘How was it? Was it awful?’ she asked, taking our coats and fussing over how smart we both looked in our black suits.

‘No, it was OK. I mean, horrible.’ I shook my head, grimacing. I’d told her Marcus was someone I used to work with years ago. She pointedly hadn’t asked for any further details.

She brushed an invisible bit of lint from my lapel. ‘You both look so handsome. Don’t they, Alex?’ My dad and I share a name: it was his first attempt to impose his own personality on me, and like all the rest, it didn’t stick.

‘Hmm? Oh yes, very smart.’ He retreated and the volume went back up on the Six O’Clock News. Mum shook her head in mock frustration.

‘Actually, Sylvie, I might get changed if that’s OK?’ said Ryan. ‘Keep this nice for best, you know.’ He had a point: dry cleaning cost a fortune, especially given how frequently we needed our funeral clothes these days.

‘Oh, of course! You know where everything is.’ The routine was separate bedrooms here, even though the pair of us had been living together for two years now. It had started out that way the first time I brought Ryan home – Mum slightly over-enthusiastically showing off my old bedroom, which my dad had newly done out in top-to-bottom Laura Ashley, and she was self-consciously calling ‘the guest room’ now. Somehow we’d all avoided having a conversation about it ever since. I usually waited half an hour in my sleeping bag on the sofa after Mum and Dad went to bed before sneaking upstairs and sliding into bed beside Ryan. I got a better night’s sleep there, even though it was still only a single. So long as I made sure I was up first to make tea in the morning, it left my parents none the wiser, or at least in a position to pretend to be.

‘Of course.’ I watched my boyfriend’s bottom ascend the stairs appreciatively. It is a very nicely cut suit. Not that he doesn’t always look lovely, of course, but I’ve got too used to seeing him in the saggy nylon uniform they make him wear for his job at the security firm. He’s mostly in the office these days, with only the occasional night shift on site when they’re short-handed, but they still like him to wear the uniform to show off the alarms and stuff. Apparently the customers find it reassuring.

‘Come and help me with the tea,’ said Mum, after slightly too long a pause. I’m not entirely sure she wasn’t looking at Ryan’s arse as well.

‘How are you? Are you both well?’ she asked as she bustled around the kitchen, clattering mugs and teaspoons.

‘We’re fine,’ I told her.

‘Have you eaten? Your dad and I have had ours, but I can do you something.’

‘Don’t worry, we had something on the way.’ We’d stopped at a service station for something to soak up some of the alcohol I’d put away in the pub that afternoon (Ryan had been good and stuck to lemonade, as he was on driving duties – I only passed my test recently, and I’m still not confident on motorways). We’d ended up staying at the pub longer than we probably should have, reminiscing about Marcus and other personalities from the old days. I’d scoffed half a packet of Polos afterwards so my parents wouldn’t know I’d been drinking: as so often, I seemed to be reliving the teenage years I’d missed out on.

‘We’re both on the Weight Watchers at the moment,’ Mum told me as she scalded the teapot. ‘Your dad’s been warned about his cholesterol. Dr Grant had him in. It turns out he’d been getting these pains in his chest for months. He thought it might be angina.’

‘What?’ I said, alarmed. I couldn’t live with my dad – an occasional overnight visit, two nights at a time max, was the most I could manage before we had a major falling out – but living without him was equally unthinkable.

‘Don’t worry – it turned out to be nothing. Bit of heartburn is all. But we could both do with shifting a bit of weight, so it’s diets for both of us.’ She tapped a tummy that, as far as I could see, was barely there. ‘You open some biscuits if you like.’

‘No, I’m fine.’

‘Didn’t say anything to me, of course. I mean, why would you? I’m only a nurse! If you’ve got a medical professional in the house, why bother talking to them, eh? You alright love?’

I shook my head. ‘I’m fine. I’m just going to go to the loo.’

I passed Ryan, back in jeans and a T-shirt, at the bottom of the stairs. ‘Are you OK?’ he asked, reaching out an arm towards me.

‘I’m fine,’ I repeated, like a broken record, and disappeared into the downstairs toilet.

It actually ended up being a really nice evening. Blackadder was on, which neither of them had ever seen before because they suspected it was ‘a bit cheeky for your dad’. But it wasn’t too rude an episode, thankfully, and both of them were soon laughing their heads off.

By ten o’clock Mum and Dad were yawning. ‘Let’s just have the headlines before we go to bed,’ Mum said, choosing an unguarded moment to slip the remote control off the arm of Dad’s chair to switch over to ITV.

Thankfully, given the way my father can rant at the news, it was mostly about the ongoing court cases over Spycatcher, which even he was bored of by now. The saga surrounding the memoirs of a former MI5 spy felt like it had been going on for years, with the government throwing everything they could at preventing the book from being published, not just in Britain, but all over the world.

A legal case in Australia had already ended in humiliation after Maggie’s cabinet secretary admitted in the witness box to being ‘economical with the truth’ – which appeared to be a posh way of saying ‘lying’. Now the government had lost another trial in London, trying to uphold injunctions against the British newspapers, which had been slowly dribbling out the contents of the book for months, but they’d announced they would take it to the Court of Appeal. That meant the whole thing was going to go on for months more.

‘What time have you got to head off in the morning?’ asked Mum as she brought the tray in with their last cup of tea of the night during the advert break. This one still came with a biscuit, although it was only a plain digestive so it didn’t really count.

‘Oh, no real rush,’ said Ryan. ‘I’ve got tomorrow off work, too, and it’s your half-term, isn’t it?’

He turned in my direction, beaming. If we hadn’t both been sprawled at opposite ends of the sofa I think I would have kicked him.

‘Oh, stay for the weekend then!’ urged Mum, predictably.

I think Ryan would probably have been willing to. For all the weirdness with my dad – which Ryan always insists is mostly in my own head anyway – I think he likes spending time at my parents’. I guess anything is better than the treatment he gets from his own mum and dad, who are determined to ignore my existence entirely. He had gone back to Belfast to tell them he was gay just before we moved in together. It wasn’t my doing, but Ryan had insisted it was the right thing to do. That Catholic confession gene, I guess. A couple of days of excruciating radio silence had followed before he arrived back on my doorstep looking like death and just shaking his head when I asked how it had gone.

‘She crossed herself,’ he finally admitted a few days later. ‘My own mammy actually crossed herself when I told her, and told me not to tell my daddy because it would surely kill him.’ He had gone ahead and had the conversation anyway. And apparently his father had just shaken his head, and walked away into the next room, and from that day to this it had never been referred to again, despite Ryan being expected home to do his duty at every single Christmas and christening and first Holy Communion and confirmation in the extended Coyle family ever since, invitations very definitely not plus-one. It was almost enough to make me feel grateful for my own dad.

Not grateful enough to want to spend more than 48 hours at a time in his company, though. I turned the invitation down as tactfully as I could. ‘We can’t really. I’ve got lessons to plan and stuff for next week. And marking.’

‘Of course.’ Mum looked disappointed, but she also couldn’t help smiling at the mention of work. I don’t think she’d believed I was ever going to get myself a proper job. Given that I was demonstrably hammering two of the three Rs into young minds, even my father, whose approach to education could have been described as Gradgrindian if he’d have had the first clue what that meant, approved.

‘You still enjoying it?’ she asked.

‘I really am.’

I’m not saying every moment was fantastic – there were days, when I was covering two different after-school activities because the permanent staff were working to rule on NUT orders, or trying vainly to get the third year ‘C’ set to grasp basic grammar in the temporary classrooms with rain dripping into buckets, that it all felt pretty dismal. Budgets had been slashed so viciously that they could only afford to have me there, even on my probationary wage, for four days a week, which didn’t exactly bode well for the future of my employment, or the education system in general.

But there were moments in nearly all my Monday-to-Thursday weeks – several sometimes – when you could see young eyes lighting up with the same excitement I used to feel when I was losing myself in the world of a book, and then it felt like the best job in the world. On the really good days, I might even say it felt like I’d found what I was born to do.

‘I’m so glad. We’re very proud of you.’ She drained the last of her tea, and stood up, turning to my dad. ‘Right you, come on. Bedtime.’

Dad stood up obediently and followed her out of the room with a ‘Night all’. Once the lounge door had closed behind them, I administered the kick I had been itching to deliver to Ryan’s leg, although I did it very gently. ‘Idiot.’

‘What?’ he asked, gormlessly.

I imitated his accent. ‘Ooh, noo Sylvie, we’ve got nothing on all weekend, we can stay forever. Divvy.’

He shrugged. ‘I’m having a nice time.’

‘You wouldn’t once Dad and I start rowing.’ I got up to search for the remote. Dad had repossessed it as soon as my mum had gone out to make the tea, and stashed it on the far side of his armchair so she wouldn’t be able to take it back again. I extracted it from his pile of back issues of the Daily Express and clicked the set off.

‘I mean, look at all this.’ The topmost paper had been folded back to an inside page with a full-length photograph of Maggie Thatcher on it. I picked it up to show Ryan. The prime minister was wearing a shimmering ballgown, and was arm-in-arm with a florid-faced man in a dinner jacket: the headline above it read ‘CONFERENCE SUPERMAG IS BELLE OF THE BALL’.

‘Jesus,’ agreed Ryan with a grimace.

‘He’s probably kept this out to have a wank over.’ That was gross, even for me. Why had that popped into my head? The man looked oddly familiar from somewhere. I knew that round, jowly face and the waves of his hair, as neat as if he had pressed them in with his fingers, but the image I’d conjured up was so grotesque that I dropped the paper back into the pile without reading any further. ‘Come on. I could do with an early night too.’

‘Right you are.’ Ryan got up from the sofa, leaving it free for me, at least theoretically. ‘See you in a bit then?’

‘The second the coast’s clear,’ I assured him, and started to shake out the sleeping bag across the sofa cushions for appearances’ sake.

four

It’s cold tonight, the autumn wind cutting straight through the thin cheesecloth of your shirt. You wish you had a coat, but looking good is more important than feeling good. Looking available more important than being comfortable.

Your belly’s empty too, hunger gnawing away at your core. You look enviously at the red glow of the Wimpy Bar across the way, your mouth watering as you plan the feast you will get once you have turned the trick that will earn it for you: the Hawaiian Burger probably, or even the Special Grill, and even a sundae for afters if you have a particularly good night. If. Because so far this has been a very bad night indeed.

Bad night for you, but not the others: Lee has been in and out of the lavs like a cuckoo in a clock all night, and Luke disappeared off to the Regent Palace with some suit the best part of an hour ago. Looked like a big payer, too. Luke’ll be good to lend you some dinner money if things get desperate: he might even treat you, he’s generous like that. No sign of Olly tonight. He’s picked up a regular, a guy who lives up Bayswater way. Works in the record industry, apparently.

Came cruising down the Dilly in his big car a few weeks ago: trolling round and round the roundabout giving Olly the glad eye until he finally pulled over and stopped outside Lillywhites, got out and leant against the driver’s door waiting for him to go strolling across. Which of course Olly does. Bold as brass, he asks him, ‘You lost, mate? Can I give you directions?’ And in they both get and off they go. You hoped from the way he had been scanning the meat rack he might be after two boys, but he only had eyes for Olly.

Can’t blame him. Olly looks like a blond David Cassidy. The nights when you get to do threesomes with him are the best. Especially when you get to thinking about them afterwards, and in the version that runs in your head you can edit the punter right out and just leave the two of you to get on with things yourselves.

‘Ay, wake up daydreamer!’ Lee appears next to you at the railing, making you jump. ‘You’re not gonna pick up much action staring off into space like that.’ Lee’s new, a breath of fresh air on the Dilly. A cheeky chappie, your mum would call him – but no, you don’t want to think of your mum. A Scouser, fresh off the train a few weeks ago but already acting like he owns the place. You couldn’t believe it when he told you he was only fourteen.

‘How’s it going?’ you ask him, although you already know.

‘Busy down below,’ he grins. ‘You want to get yourself down there.’

You sniff. You don’t like working the toilets unless you have to. Not with the smells, and the noises, and the high chance that every punter you might even remotely fancy is going to turn out to be a pretty policeman with his cock in one hand and his warrant card in the other. But needs must as the devil drives. You really are hungry now. ‘Maybe in a bit,’ you tell him.

‘Right you are, Bookworm.’ He turns and leans back on the railing, letting his t-shirt ride up to show off a few inches of taut tummy. ‘Oh, here comes some company for you anyway. Little Lord Fauntleroy.’

You don’t know why he calls Marcus that. Marcus isn’t even that posh, but he made the mistake a while ago of admitting in front of Lee that he’d run away from boarding school. ‘Ooh, hark at Prince Edward,’ Lee had mocked, doing the weird tippy-toed mincing parody that came easier to him than he might have liked to admit. You’d admired Marcus’s response. He hadn’t hit him, or got angry, just stared him down deadpan and drawled, in an accent that was definitely a few tones above any of the rest of us, ‘Why, was his games master fucking him too?’

‘Evening gents,’ he says now. ‘Much happening?’

‘Not for this one,’ Lee cuts in before you can say anything, slapping you on your arm in a gesture that’s friendly, but still hurts. ‘He’s strictly on a nil-by-arse diet tonight. Eh lad?’

You don’t even bother to return his mocking smile. ‘Bit slow,’ you admit, with a nod to Marcus.

‘Well, we’ll have to see what we can do about that.’ Marcus pulls out one of the John Player Carltons he insists on smoking, sparks it up with the gold lighter he got off a punter – gold-coloured, at least – and then turns, leisurely, to blow smoke in Lee’s direction. ‘Don’t let us keep you. I’m sure there’s a toilet cubicle with your name on it down there. Or just the description. Va-cant.’ The way he pronounces his vowels, he might mean either of two things, one pretty rude, one very rude. You can’t help sniggering.

‘A-right, a-right,’ says Lee, groping for a snappy comeback. ‘Just ’cos some of us have to actually work for a living,’ is the best he can manage, and he turns on his heel and stalks off again towards the Underground steps. But before he gets there he turns again and comes scuttling back, ignoring Marcus and addressing you directly. ‘Come’ed, Tommy, here’s an easy one for you. Auld fella there on his way down. Get after him. He’ll give you a tenner for a blowie. Too pissed to even come half the time. You have him as my treat.’

You look sceptically in the direction he’s pointing. The man doesn’t look like much of a treat, hefting himself carefully down the stairs hanging heavily on to the handrail, obviously wary of taking a tumble. Despite Lee’s description he doesn’t look all that old, at least not by Dilly standards. Which means that walking like that, he’s probably drunk instead. It’s still pretty early in the evening, so he’ll have been on an all-day session. Looks respectable though, you have time to clock as he disappears beneath ground: nicely-cut suit, tie, and pocket square, light red hair that looks like he’s pressed it into waves with his fingers. No obvious danger signals. But then they’re not always obvious until you’re crammed into a cubicle with them.

‘Go on, get after him!’ orders Lee, with another hard slap on your back, and you’re propelled forward towards the steps before you have time to consider it any more.

You spot the man again as you get to the bottom of the stairs, and, just as predicted, he’s making a beeline for the gents, treading a well-worn, if slightly unsteady line through the circulating crowd of travellers. A quick scan of as much of the concourse as you can see around the curves: no obvious coppers hanging around, so you take a deep breath and head after him.

The stink hits you the second you enter the underground room. But you do your best to ignore it. The urinals are all occupied – you scan the backs quickly but can’t spot your man – and then you realise he’s not messing about: he’s already over at one of the cubicles, standing there looking out through a half-closed doorway, swaying a little and actually licking his lips. Now you get a proper look at him he’s even less attractive than you thought – a great red moon-face and bushy eyebrows you can see drops of perspiration glistening in. The sweat pouring down his forehead suddenly makes you think of Bernard Manning. And that in turn brings to mind your father sitting in his armchair in front of The Comedians, laughing and laughing until the tears stream down his face. But you’re not going to think of that. No way. Push that down, out of sight.

Besides, beggars can’t be choosers. The man has spotted you, and his hand has already gone down to the crotch of his suit trousers and is rubbing away as he leers in your direction. If you’re not in there with the door closed in a few seconds he’s running the risk of getting you both arrested.

At least you will make sure you get the money up-front. Sighing, you step forward towards the cubicle.

And the door BANGS shut behind you.

‘What was that?’

I’d managed to fall into a deep sleep despite being squashed awkwardly up against the wall with Ryan wrapped around and half on top of me. But it can only have lasted a couple of hours before the noise from outside pulled me back into consciousness and I sensed him wide awake beside me.

‘It’s the wind,’ he said in the darkness. ‘It’s really got up.’

It was absolutely roaring, making the bedroom window rattle and what sounded like the very structure of the house creak. Every few seconds the sound would lessen and I would think it was dying down and the place was going to get some respite, but then it abruptly redoubled, each gust bringing other echoes: objects crashing and clattering about outside, the distant sound of car alarms, and a rhythmic thumping from somewhere nearby.

‘Something’s banging,’ I said, still groggy with sleep. At least half of me was still stuck in my dream: how weird to be so vividly back in the Dilly after all this time. It must have been the reminiscing in the pub that set it off.

Ryan sat up, disentangling himself from the muddle of limbs, and reached over me to click the bedside light on. The curtains were actually wafting out into the room, even though the window wasn’t open. ‘Yeah. It’s in the garden, isn’t it?’ Each loud bang was followed by a series of diminishing quieter ones: BANG-bang-bang-bang, BANG-bang-bang-bang.

I was trying to get my bearings, think where the noise might be coming from, when a door creaked on the landing and we heard footsteps thumping downstairs. They were closely followed by an urgent tapping on the bedroom door. My mother’s voice came floating through: ‘Ryan? Sorry, love, are you awake?’

It was too late for me to hide under the bed, and it’s a solid base one anyway. Ryan shook his head and shrugged, then called out ‘Yeah, hang on, Sylvie. Just give me a minute.’

He clambered over me and out of bed. We were both perfectly decent, in t-shirts and boxer shorts, but I really didn’t want her to see us crammed like sardines in the single bed together. At least it sounded like my dad was already out of the way: I could hear the rattle of keys in the front door and then suddenly the noise of the wind swelled in volume as he threw it open. Was he really going out in this?

Ryan, meanwhile, had made it to the bedroom door and pulled it open just a crack. ‘Sorry to disturb you love, it’s just Alex has insisted on going out there to see what’s blowing about and I wondered if you two would mind going with him to make sure he’s OK. It’s a heck of a storm.’

‘Yeah, of course.’

Ryan turned away from the door to look for his trousers, and Mum took the chance to shove it slightly further open. ‘Oh, you’re there too, Alex.’ She didn’t sound surprised. Or particularly disapproving.

‘Hi Mum,’ I muttered, swinging my legs out from under the duvet, taking my time to check I definitely wasn’t displaying anything I shouldn’t be. ‘Mine are…’ I pointed downstairs.

‘Yes, yes.’ She stood aside to let me pass and go and fetch my own jeans and shoes from the lounge. She was in her slippers and dressing gown, one hand clutching the fluffy lapels up anxiously around her throat. ‘I said he should wait for the pair of you, but he wouldn’t listen, you know what he’s like. He thinks there’s something got loose in the garden.’

‘Don’t worry,’ I called up as I hurried downstairs. I could feel the full blast of the wind rushing up to meet me through the open front door, which was flattened right back against the wall. My bare legs erupted in goose pimples, and my balls went up somewhere near my armpits.

‘Be careful. There’s bin lids and all sorts blowing around in the road out there.’

I bit back a ‘no Mum, we weren’t going to bother’ – my internal stroppy teenager always surfaces when I come home to visit – and instead took out my frustrations by yelling ‘Wait for us, Dad,’ into the howling gale as I passed the open door. The phone book on the hall table had been thrown open, its pages flapping. The coats on the pegs beside the door were dancing about like there were people still inside them.

It only took me a few seconds to scramble into my clothes and shoes in the lounge. Ryan was already in the doorway waiting for me, Mum hovering behind him. ‘Ready?’

‘As I’ll ever be.’

We headed out into a maelstrom of indigo sky. The wind was so strong I actually had to plant my feet down on the front step and brace myself against it.

‘Christ, look at the way the trees are thrashing around!’ Ryan yelled. The conifer in the middle of the front lawn, which is as high as the house now, was whipping back and forth, its neat tapered form splintering into jagged fractals, tiny ones detaching themselves at the edges and whirling off into the night sky. The neatly clipped privet that screened the front garden from the pavement had transformed into something seething and alive.

‘This is mental!’ I tried to say to him, but I could barely even hear myself.

Ryan turned and stuck his head back into the house. ‘Sylvie, close this door behind us,’ he shouted, even though she was just a few feet away. ‘Listen out for us knocking to come back in again, yeah?’

My mother, white-faced, nodded her assent, and then we were alone and out in the storm.

five

For a moment, as I fought my way out onto the front path, I wondered if I hadn’t woken up at all. Everything had that strange dream-feel where things are both familiar and utterly wrong. This was the garden of the house I’d grown up in, but it had been transformed.

There was no sign of my father anywhere. It was as if he had been swallowed up by the storm. Mad, storybook images flashed through my head: grown men floating away beneath bunches of balloons, or Magritte-style umbrellas. Dorothy on her way to Oz.