Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The O'Brien Press

- Kategorie: Für Kinder und Jugendliche

- Sprache: Englisch

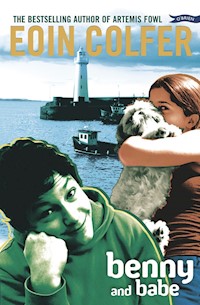

Sequel to the No. 1 Bestseller Benny & Omar Benny, the sports-mad, carefree lad whose adventures in Tunisia have convinced him that he can take on the world, suffers a severe blow to his pride when he meets Babe. He may be a wise guy, but she is at least three steps ahead of him. And he's on her territory. Benny is visiting his grandfather in the country for the summer holidays and finds his position as a 'townie' make him the object of much teasing by the natives. Babe is the village tomboy, given serious respect by the all the local tough guys. She runs a thriving business, rescuing the lost lures and flies of visiting fishermen and selling them at a tidy profit. Babe just might consider Benny as her business partner. But things become very complicated, and dangerous, when Furty Howlin also wants a slice of the action. And that's not the only problem for Benny. A disco reveals a transformed Babe– can they still be friends now that she is a real girl? Benny and Babe was shortlisted for the Reading Association of Ireland Award 2001.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 298

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2012

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Reviews

About Benny and Babe

‘One of the most sustained pieces of comic writing I have ever come across in an adult or children’s book’ROBERT DUNBAR, PAT KENNY SHOW, RTÉ

‘The best thing about Benny is his thinking patterns – if you don’t recognise yourself and a dozen friends somewhere in here, you’re probably an alien’RTÉ GUIDE

About Benny and Omar

In the first book about Benny, set in Tunisia while his family is living there for a year, he teams up with Omar, a local wild boy living on his wits. Between them they are more than able to create havoc.

‘A wonderful book, absolutely hilarious’GAY BYRNE SHOW, RTÉ

‘There is hardly a page which will not have a reader laughing aloud’THE IRISH TIMES

‘Colfer smoothly layers adventure, moments of poignancy and subtle social commentary, and his comic timing is pitch-perfect’PUBLISHERS WEEKLY

For Noreen and Billy

CONTENTS

Reviews

Title Page

Dedication

Prologue

Culchie Hurling

Childish Things

Pax

Arch Enemy

Bait Wars

Disco King

Mask and Flippers

Square Pegs

Black Chan

Hell to Pay

About the Author

Copyright

Other Books

PROLOGUE

Whenever Benny Shaw remembered the summer, fear drained the strength from his legs and set his heart bursting against his ribs. The mere sound of scraping metal sent twinges rippling across his knee. Close one, Benny me boy, close one!

A lot of things had happened last summer, not all of them bad. There were the baits, the discos, Black Chan, and, of course, Babe. Benny smiled at the thought of her. They still kept in touch. Sort of. A letter once in a while. Maybe an accidental meeting on the main street if she was in town buying jeans, or whatever else you couldn’t get in those culchie shops in the back of beyonds. Not a whole lot really for two people who were supposed to be partners for life.

One day in August had put paid to all that. Babe got a look at what he was really like and decided she was better off without him. This was pretty deep thinking for a young chap, but Benny had been doing a lot of that since the accident. It wasn’t as if he had anything else to do. It wasn’t as if he was going hurling or anything. Benny searched his knee with a magnet till it clinked on to the steel pin under the skin. Nope, it wasn’t as if he was going hurling.

Actually, hurling was how the whole thing started. A parentally approved occupation. And one he was good at too. But trouble is like that. It sneaks up on you quietly. One minute you’re enjoying an innocent puck about, and the next, half the Irish Sea is flowing down your throat, and there’s a one-eyed mongrel dog hanging off you.

It wasn’t real hurling anyway. It was culchie hurling. And in culchie hurling, the rules are a bit different.

CULCHIE HURLING

Duncade was the best place in the world. A small fishing village nestled in the cliffs of southern Wexford. The cove was dominated by Dugan’s Tower, a lighthouse named for the Welsh priest who’d hammered Christianity into the locals. Tourism was not encouraged, and the privileged group of annual visitors was sworn to secrecy. It wasn’t everywhere that leaning over a quay wall spitting after the tide was considered an honourable pastime. Nobody wanted to jeopardise that. Benny was one of the lucky few. Because his Granda was the lighthouse keeper, his family were accepted as legitimate guests by the clannish villagers.

The Duncade boys had put together a couple of hurling teams. Not full size or anything, just eight on eight. Or more accurately, eight boys on six boys, a girl and a dog. They came up to the lighthouse looking for Benny, seeing as he spent every daylight hour bashing a ball against the gable end.

‘Okey dokey,’ said Benny with a big innocent look on his face. After all, how good could these farmer boyos be? Probably spent most of their time running drills with cows and sheep.

‘Don’t worry, Ma, I’ll go easy on them,’ he roared up the lighthouse’s spiral staircase.

His mother muttered in response, too immersed in the day’s artistic endeavour to waste any words on her eldest son. Jessica Shaw was a drama teacher with a real passion for her subject. Her current obsession was poetry. She spent hours in the light room thinking of fancy words for sea and clouds.

I mean, poetry for God’s sake, fumed Benny. Cat, bat and mat. What was the point of it? If you want to look at the sea, go over to the window and have a look. If you want to describe it, buy a camera. All this sorrowful waves and angry clouds bit was for people who were useless at hurling, and therefore had meaningless lives.

Like, for instance, his little brother George, aka The Crawler. He was his mother’s boy all right. Sitting out on the rocks communing with nature. Benny threatened to let his boot commune with Georgie’s backside if he had to listen to any more poems. His latest act was poetic sentences. Whatever the little eejit said had to rhyme. And he refused to answer at all until he thought of a good one.

‘George! Come in for your tea!’

‘I can’t wait / for my plate.’

‘Shuddup with all that poetry stuff, will ye?’

‘I must rhyme / all the time.’

‘I’m warning you. Y’see that fist?’

‘If pain I feel / I will squeal.’

Enough to drive a person mental. At least you could be certain there’d be no sign of the little pest at a hurling match. Georgie considered sport in general to be the pastime of savages.

‘He who hurls / is a churl.’

Benny wasn’t sure what a churl was, but one day he’d find out and then, Crawler beware!

The Duncaders were sitting on a famine wall, chewing hay and kicking cowpats, among other wooller occupations. Benny flattened his cowslick and ambled over, nonchalantly hopping a sliotar on his hurley.

‘How’s she cuttin’ there, men?’ he said, using the vernacular.

‘Shaw, boy! That’s a nice stick you have there.’

‘Sure it’s a grand bitta wood,’ said Benny, really laying on the accent.

A big massive barn of a chap stood up. Benny swallowed. He’d thought the fellow was already standing. ‘Holy God, Paudie, you’re after sprouting.’

Paudie was only fourteen, a year older than Benny himself, and already the size of a round tower.

‘Must be all them bales of hay you’re throwing around.’

‘S’pose.’

Paudie hefted a hurley the length of a telephone pole. Jagged nails poked out of the rusty bands at its base. There was a dark stain on it that looked suspiciously like blood.

‘I’m on your team, am I?’ said Benny.

‘S’pose.’

Benny swallowed a relieved sigh. ‘Good stuff. Are we right then or what?’

He climbed over a steel gate. The struts were drooping like an old clothes hangers from the passage of a million others too lazy to open the catch. The surface of the pitch left a lot to be desired. There seemed to be a bit of a fairy fort in the centre of the field, and the odd sheep was searching for edibles among the scutch.

‘Ah here, Paudie. You can’t even see the other goal. Would you boys ever get your act together.’

‘A bit tough for ye, is it, townie?’

The voice came from below his sight line. Benny glanced down. What appeared to be a pixie was glaring up at him. The creature spoke again.

‘I told ye, lads. No guts.’

Benny would have spluttered a denial, if he hadn’t been afraid of a fairy curse or something. Then the pixie took off her woolly hat and flicked her hair out of her eyes.

‘God!’ said Benny.

‘What?’ said the pixie.

‘Ah … nothing,’ muttered Benny. What was he going to say? I’m sorry, young lady, but I mistook you for a mythological creature? Benny may not have been Mister Millennium, but he was no gom.

‘Well, let’s get the show on the road then,’ said the pixie, twirling a midget hurley like some kung fu baton.

‘Fine by me.’

‘Sure ye don’t want to scamper off home for a helmet and some pads?’

‘Keep it up now.’ Benny just knew his cowslick was standing at attention.

‘And what? There’s no ref here, boy.’

Benny rolled his eyes skywards, demonstrating, he hoped, what an immense feat of patience it took for him to suffer this strange girl’s ramblings. ‘Paudie! Are we playing or what?’

Paudie swiped playfully at a cowpat, sending it sailing over the boundary fence. Benny winced. There were campers in the next field. ‘S’pose.’

The teams shambled into some semblance of a formation. Benny automatically assumed the full-forward position. They’d probably put some big monster of a lad on him, but sure he was used to that from playing the Christian Brothers School back in Wexford. Some of the juveniles on their team were at least twenty-four.

‘Who’ve I got?’ he shouted across at Paudie, who was busy nudging a belligerent ram out of the area.

‘Me,’ said a voice.

Benny looked down. It was the pixie.

‘You?’

‘That a problem for you, townie?’

‘No problem at all, wooller. Just don’t get yer head in the way of me hurley.’

The girl whistled softly. ‘I wouldn’t be making threats. He doesn’t like it.’

‘Who’s that? The pixie king?’

‘No. Him.’ She nodded at a cowpat.

Benny followed her gaze. The cowpat was growling at him.

‘That’s Conger. He hates townies.’

The little mongrel was about the size of a saucepan, and seemed to be made of brown electricity.

‘And how does the mutt identify townies? By the smell of soap, is it?’

Benny never did know when to keep his trap shut. The dog seemed to sense antagonism because he aimed his snout at Benny, and closed one eye. The other was a milky blue haze with no iris or pupil.

The Duncaders froze.

‘The eye!’

‘Conger’s given the evil eye.’

The pixie shook her head and crossed herself.

‘Ah here,’ snorted Benny. ‘A devil dog. Get a grip, will yez?’

He noticed a space widening around him. No-one wanted to be too close when Conger made good on his voodoo promise.

Benny, being Benny, wasn’t convinced. ‘Never mind all this psyching me out rubbish. I’ve played in Croke Park.’

Paudie strolled over, mild annoyance wrinkling his generally blissful brow. ‘Here, Babe. Keep a leash on the mutt until we start the game.’ Conger didn’t bother giving Paudie the evil eye. He wasn’t stupid.

Two things struck Benny, and his mouth went into action before his brain had a chance to paste a government warning over it. ‘Until we start the game? You mean, the dog’s playing!’

Paudie shrugged. So what?

‘And Babe. What sort of a name is Babe?’

‘Better than George and Bernard Shaw,’ sneered Babe the pixie.

Benny, for the millionth time, silently fumed over his mother’s obsession with literature. Imagine being one half of a playwright’s name! For years he’d been trying to think of a comeback for that slur, and he still couldn’t manage it.

‘Yeah well …’ he said, trailing off lamely.

Babe rolled her woolly hat back over a shock of curly hair. Victory was hers.

Benny glowered at her. Babe by name, but most certainly not by nature. You win this battle, Obi Wan, but the war is far from over.

The ball went in. Benny, naively assuming they were playing strategy, held his position. The rest of them bulled into the centre, diving into a writhing mass of limbs.

Babe was itching to join the fray. She snapped her fingers at Conger.

‘Mark the townie, boy,’ she commanded. ‘You know what to do.’ And she was off, disappearing up to her neck in culchie flesh.

Conger gave a little yip, turning his bandy gaze on Benny.

‘What happened to your eye, Conger? Hurt yourself drinking out of a toilet, did you?’

Conger tensed, baring nasty little incisors. That look said: keep it up, townie, let’s see what that Wexford leg tastes like.

The tangle of bodies on the pitch was like one of those cartoon frays. Benny half-expected to see stars and the word POW appear in fluorescent colours above the dust. Incredibly, it was Babe who emerged with the ball. She was flailing all around with her hurley. Paudie fell, smitten under the chin. He had the glazed look of concussion in his eyes. But then, Paudie had that look at the best of times.

Benny narrowed his eyes against the sun. Time for God-given talent to make its mark. He mapped out the move in his head. Nip in, a little illegal trip for that smartalec Babe girl – nothing painful, just flat-faced humiliation – then scoop up the free ball, and fire it in for an easy point. Or goal, depending on how far it went over the pile of jumpers that were the makeshift goalposts. Simple for a young man of his ability.

Stage one went according to plan. Benny bent low and nipped in towards the culchie stew. Babe tumbled out of the scrimmage just as he got there. Their eyes met. Or rather his eyes met her curly fringe. Benny gave his best vulpine snarl. And the girl made her move.

Perfect. So predictable.

Benny stuck out his foot for the trip. Except there was no girl, just a little lump of dog, chewing on the toe of his runner. Babe had dummied him and was halfway to the other end of the field. Benny didn’t know which offended him more: being suckered by a girl, or catching rabies from her mongrel. Squealing like a teething baby, he tried to slap the dog off with his hurley, but only succeeded in bashing himself on the shins. Babe, meanwhile, had tapped the sliotar into an open goal.

Benny soon copped on to the trick of dealing with Conger – the miniscule dog applied pressure only if you moved. He was forced to stand stock-still on one foot until Babe made her way back from the goal. By this time a whole tribe of culchies was gathered around snickering.

‘Laugh it up, farmer boys,’ said Benny in a friendly tone, in case the dog was sensitive to that sort of thing. ‘Soon as I get muttley here off me foot, you better watch that goal.’

‘Problems, townie?’ All you could see of Babe’s head was hair and a grin.

‘Me? No. Everything’s fine, thanks very much, except for I’m about to kill this stupid dog if you don’t get him off me foot!’

‘Be careful there, Shaw. He can smell fear, you know.’

‘Fear!’ Benny squeaked. ‘Who’s afraid?’

He felt a needlelike tooth jittering on his big toe, and willed his pulse to slow down.

Babe sighed. ‘I suppose I might as well save poor townie from the big bad doggie.’

She snapped her fingers again. ‘Conger! Throw him back.’

Conger spat out Benny’s foot as though it smelt worse than a barrel of old fish, which in fairness …

Benny wiggled his toes experimentally. Everything flexed normally. ‘Lucky for that dog you did that. I was about to –’

Conger growled. Benny shut up.

By this time Paudie had hauled himself out of the muck.

‘One–nil. That was your fault, Benny. Babe is your man. Right, face up for the puck-out.’

It was no good. Benny’s nerve was gone. It was bad enough being uncertain about whether to flatten a girl or not, but on top of that there was the dog growling every time the sliotar came anywhere near them. He barely won a ball. It was embarrassing. Humiliating. If he’d been a racehorse, they’d have put him out of his misery.

Full time. Six-goal advantage for the opposing culchies. Benny felt like jumping off the end of the quay. Knowing his luck, the tide would be out. He tried to slink off home unnoticed, but Babe was having none of that.

‘Hey, townie, going home for a sob, are ye?’

Benny smiled widely to demonstrate just how un-upset he was.

The Duncade girl laughed. ‘Don’t worry, townie. You can play with the juniors next week.’

Of course, all the other culchies thought this was hilarious. Who cared which team you were on as long as the townie got slagged.

‘Yeah, yeah, yeah,’ said Benny, painfully aware that this was a pitiful excuse for a smart comeback. Struggling against an instinct to bolt for the lighthouse, Benny casually vaulted the gate and strolled up the sea road.

Usually Benny Shaw considered himself a bit of a wit. Not in a Shakespeare-play fashion, but in a one-of-the-lads-trading-insults kind of a way, but this wall of chuckling farmers totally unnerved him. He needed professional help to deal with these people. Time to talk to Granda.

Paddy Shaw was one of your original mariners. The kind that didn’t need instruments to tell them which way was north. In a nautical career that spanned over half a century, Benny’s Granda had sailed around the world, captained a deep sea trawler, and indulged in several quasi-legal ventures, that some cynical types might refer to as smuggling. He was living out his retirement as keeper of Dugan’s Rock lighthouse.

Benny trudged up the spiral staircase and stepped out on to the cast-iron platform. As usual, the view robbed the words from his mouth. Dugan’s peninsula stretched north-west to the lights of Wexford and south to Rosslare. Every five seconds the massive light swung around and painted the night white.

The Captain was rolling a pencil-thin cigarette from a pouch of pungent tobacco. The pouch, Granda claimed, was made from the scalp of an Australian who’d tried to mug him in Borneo. It was very unwise to mess with Paddy Shaw. Local legend had it that he had once keelhauled a pot poacher. Granted it had been under a dinghy, but that was only because Granda had been in a dinghy at the time.

‘Howye, Granda.’

‘’lo, boy.’ Granda struck a match, making a lantern around it with his folded hands.

‘How’s the tower, Captain?’

Paddy Shaw grunted. ‘Sure, I don’t know. You better ask the computer. All I do is check all the little lights are green.’

‘Granda?’

‘Hmm?’

‘Granda, I had a bit of a game today.’

‘Is that right?’

‘Yeah. With the cul… with the locals.’

Granda chuckled, a phlegmy rumble, full of fags and whiskey. ‘I see. Got an education, did ye?’

Benny wiggled his toe inside the trainer. ‘Yep.’

‘I’m sure it’s not the first time ye’ve had the stuffing pucked outta you. Do you no harm to lose a bit of that cockiness.’

Benny nodded patiently, fully aware that adults felt obliged to give a bit of a lecture before actually helping with anything. ‘There was a girl, Granda.’

‘Oh, now we’re getting to it. Woman trouble, is it? I remember one time in Madagascar, I spied this dusky beauty washing clothes in the river. The problem was that the tribal elders wouldn’t –’

‘It’s nothing like that, Granda. It’s just she kept beating me in tackles. Her and her stupid dog.’

Granda guffawed. ‘You’ve met Babe and Conger?’

Benny nodded ruefully.

‘Babe Meara. An Amazon like her mother. Moved down here from Hook Head last winter. Don’t get on the wrong side of the Mearas, Benny.’

‘Too late.’

Granda shrugged. ‘Ye’r living on borrowed time so. Them Mearas are like the Sicilians. Never forget anything.’

‘What’re you supposed to do, though, when a girl is tackling you? I can’t just be hopping off her like I would a lad.’

Granda turned suddenly serious. ‘You want to get Babe Meara?’

Benny nodded.

‘You really want to get her?’

Benny kept right on nodding.

‘Then you’ve got to play the game her way. No prisoners. She sends one of your team to the hospital, you send one of hers to the morgue. That’s the Duncade way, and that’s how to get Babe Meara.’

Benny frowned. ‘Granda?’

‘Yes, boy.’

‘You robbed that outta that film The Untouchables, didn’t you? Sean Connery said that to Kevin Costner.’

Granda was unrepentant. ‘Robbed it? Sure it was me that used that line in the first place. Them Hollywood fellows must’ve robbed it from me.’ Granda said all this with a very straight face, so Benny decided to believe it.

‘Right, so. No prisoners.’

‘That’s it, boy. Unless, of course, there’s something else going on here besides hurling.’

Benny licked a palm and flattened the salt-stiffened ancestral cowslick. ‘What is it about women, Granda? Why are they so different? Take Ma, for instance.’

‘A wonderful woman, your mother.’

Benny found himself agreeing. ‘I suppose. But all this drama stuff …’

Paddy Shaw lowered himself on to a fish-box seat. He slapped the plastic beside him. Benny sat. Granda pulled off his denim hat, his own grey cowslick sticking up like a vertical pig’s tail.

‘You’re a good man with a hurley, Benny. But you know nothing about women. Your mother is a beautiful, intelligent, spirited lady who won’t be led around by any eejit son of mine.’

‘Granda!’

‘Ah, now … it’s grand for me to call your Da an eejit. Just like it’s grand for him to call you one.’

‘Fair enough. But the poetry, that’s not normal.’

‘You have to understand, Benny. Your mother is from Wicklow – Greystones to be precise.’

‘So?’

‘Greystones is very close to Dublin. Do I have to spell it out for you?’

Benny shook his head. The peculiarities of Dubliners were well documented.

‘It’s a them and us thing,’ continued Granda. ‘We can’t understand what your Ma brings to the family, we can just be grateful to have it.’

Benny looked doubtful.

‘I suppose you’d be happier to have a mother ironing your shorts, slapping up your dinners and having no life of her own?’

To his surprise, Benny realised that he wouldn’t.

‘Don’t try to understand city dwellers, son, but do try to avoid taking a cheque from one if at all possible.’

‘Thanks. ’Night, Captain.’

Paddy Shaw ruffled his grandson’s hair. ‘’Night, Bosun.’

Benny stepped in out of the night, climbing down the spiral staircase to his room. Take no prisoners. He didn’t know if he could flatten a girl. Then he remembered Babe Meara’s snide chuckle and he thought that maybe he’d find the resolve somewhere. And if that little dog bothered him again, he’d be sailing over the hedge like one of Paudie’s airborne cowpats.

CHILDISH THINGS

Benny was basically a loner. It wasn’t that he preferred it that way. He just seemed to have a knack of alienating people before they got to know the sensitive person under the smartalec. Way, way under.

And though Benny made no effort whatsoever to actually make friends, it didn’t stop him feeling sorry for himself because he had none. A large part of his day was spent silently berating the people responsible for his problems. There was Da for packing them all off to Duncade while he got to stay in Wexford. Then there was Georgie for not conforming to Benny’s idea of a little brother, which was more or less a ball boy. Ma was in the bad books for writing poetry with Georgie and ignoring Benny. And finally he was moody with the people of Duncade in general, for being a shower of farmers who didn’t appreciate him for the hurling prodigy that he was.

Every morning he would fume away for a good ten minutes before loping downstairs to sulk at the breakfast table. The morning after the hurling disaster he was particularly touchy.

‘Not fair.’

Jessica Shaw held back the urge to tip the jug of milk over her eldest’s head. She would, as her own mother had always advised, offer it up.

‘What’s not fair, honey?’

‘Nothing.’

‘Good. Eat your breakfast.’

Benny was tempted just to stop whining and enjoy the fry-up. You didn’t get one of those every morning, and the rashers were perfect. Crisp enough to break. But he just couldn’t resist the opportunity to voice his sorrows.

‘There’s nothing to do here, Ma.’

Jessica Shaw’s eyebrow arched. ‘Ma, Bernard? Don’t use that low-down –’

‘Sorry – Mam. I’m bored.’

‘Bored?’

‘Yes. Bored stiff.’

‘Because, if you’re really bored –’

‘I am. Stiff as a … really stiff.’ Not being a literary buff, Benny never could finish a simile.

‘As it happens, I’m planning a reading of some of my latest poems this morning. Collectively entitled “Nature the Leveller”.’

Benny paled. ‘Ah … I dunno, Ma – sorry, Mam. But I have to go and … I’d love to and all, but there’s this yoke. So maybe later, okay?’

Jessica smiled. The best way to make Bernard forget one problem was to give him another. She watched bemusedly as her eldest son crammed a hearty fry down his gullet, terrified he’d be asked to clarify his flimsy excuse. Not that there actually was a poetry reading. Still, there could be if Bernard didn’t make himself scarce after breakfast.

Benny was still chewing going out the door. The depression of loneliness was nothing compared to the brain-stewing boredom of sitting through a poetry reading. He would go down to the dock and indulge in his shameful secret pastime.

Benny Shaw had turned thirteen two weeks previously. He was a young adult destined for the CBS secondary in just under two months. And Benny Shaw had a dark secret. Deep in the pocket of his threadbare combat trousers was … a Special Forces Action Figure. Should this fact ever be discovered by a living soul, the mortification would probably be fatal. Action figures were for age four to ten. Anyone over that age caught in possession of such a figure would be deemed a big girly sissy who played with dolls. Not a nice epitaph to have carved on your tombstone. Here lies Bernard Shaw, who is chiefly remembered for disgracing all males by playing with action figures at the age of thirteen. He was also a hurling all-star, but that is rendered null and void by the doll-playing episode.

Benny knew it was wrong. He knew he’d have to emigrate back to Tunisia if anyone found out. But he couldn’t help it. Major Action listened to him. He nodded his little head sympathetically, and swivelled his beady eyes in an understanding manner. Also, you could burst Major Action off any conceivable surface and he wouldn’t break. He hadn’t so far, anyway. But today was the big test. If the Major came through this one, he could get a promotion.

Benny scratched the doll’s tennis-ball hair. ‘Take it easy in there, big fella. You’ll be out soon.’

Another curious thing was Benny’s adoption of a passable American accent whenever he spoke to Major Action. His mother would have been thrilled at the dramatic tendencies.

Benny passed the old timers spitting streamers of tobacco over the quay wall. Granda was wedged in the middle of them, his huge hands held high and wide. Looked like he was telling about finding the Holy Grail again.

George was down on the slip, marshalling a group of urchins into a line. Benny paused for a moment to check a theory.

‘One, two, three,’ said Georgie. ‘Now, all bow together.’

Benny snorted. Yep, everything his brother did annoyed him.

He strolled up the avenue to the old manor house, into what was left of the Duncade Castle courtyard. Most of the stone had been cannibalised by locals over the centuries, until only the main tower itself remained. Scheduled for restoration, it had been closed to the public for years. Only a ground-floor room, used by fishermen to store lobster pots, remained open.

Benny climbed the outside steps and hauled a manky fishbox away from a chimney flue. He held his breath and ducked inside. The chimney was wide enough for a person to climb up to the second floor, if you didn’t mind the dark or the possibility of laying your hands on some fresh cat droppings. The children of Duncade had been using this secret entrance for years. They were far too resourceful to allow a padlock and a few bars to keep them out of an actual Norman tower.

Of course you were in deadly danger every second you spent in Duncade Castle. The mud floor covered a multitude of sinkholes that could drop you fifty feet in a minute. The battlements were liable to collapse on your head at any moment, and the arched windows were just wide enough for a sarcastic little teenager to fall through. Local legend had it that Granda’s buddy, old Jerry Bent, had plunged from the tower on his eighteenth birthday. From that day to this, all Jerry could utter was the word ‘butterflies’.

Confident he was now alone, Benny pulled the doll out of his pocket.

‘Time to see what you’re made of, Major.’

The Major didn’t answer because he was terrified. (Being a doll might also have had something to do with it.)

A spiral staircase led to the tower roof. Several steps were missing, and it was a favourite pastime of the older boys to spit down on whatever poor unfortunate was making the climb behind them. Benny hopped over the gaps, imagining what it must have been like for the Celts trying to overrun a tower like this. Cramped, weighed down with weapons, not able to see more than three feet in front of you, and expecting an armoured knight to split you with a mace at any moment.

Benny followed the shaft of light ahead until he emerged on the roof. You had to stay on the battlements here because the floor was sunken and crumbling from the centre outwards. Every year there was less holding this storey up. Granda predicted that the whole thing would collapse within the decade.

Benny peeked out between the crenellations. It was pretty high. Jerry Bent was lucky he could even say ‘butterflies’. There was a spectacular view but Benny didn’t waste a moment appreciating it. For him there was only one view, and that was from the top of the lighthouse.

‘Right, Major. Zero hour.’

Benny attached the parachute to Major Action’s gripping hands. It was a home-made sort of a parachute. An old dishcloth and some worn laces. But Benny had seen a programme about skydiving once, and he was confident he’d absorbed enough information to overcome the effects of G force. How hard could it be?

If Major Action could have spoken, he would have screamed for mercy. Oh for the love of God, please don’t hurl me from this altitude, you demented Irish devil. Unfortunately, he was as mute as Benny at volunteer time in speech and drama class.

‘Any last words? No? Good. Fly, Major Action. Our hopes and dreams fly with you.’

And over the side went poor Major Action. Benny stuck his head out between the limestone blocks to follow the doll’s trajectory. The parachute was not performing as expected. In fact, it seemed to have wrapped itself around the Major’s plastic frame and decreased his wind resistance.

‘Hmm,’ said Benny, scratching his chin in scientific contemplation.

Benny’s role-playing stopped abruptly when he noticed two figures climbing the tower’s outside steps.

‘No!’ he gasped.

Fate couldn’t be that cruel. It was that odious girl Babe and her mongrel. They were standing directly under the reluctant paratrooper’s estimated point of impact.

‘No,’ he moaned. ‘No, no, please no.’

Benny would have added a few Hail Marys to his plea, but there was no time. The humanoid missile struck. Benny had read once that a penny dropped from the Eiffel Tower would impact with the destructive power of a bullet. He wondered what an action figure would do.

The doll clattered Conger on the side of the head. Spooked and dazed, the mongrel stepped sideways. Unfortunately, that brought him into mid-air, as they were half-way up the steps at the time. His fall was broken by the rancid contents of a bait barrel, full to the brim with salted guts and fish heads. Conger went right through the wooden lid, and up to his neck in fish bits.

‘Oh no!’ Benny hissed, a manic giggle threatening to erupt from his throat. It was funny, really, when you thought about it. It’d be a lot funnier if the girl had gone down. Now, there was something he’d pay real money to see.

Babe jumped off the steps and hauled Conger out by the collar. The dog began to lick himself clean, then stopped as the brine bit into his tongue. His injured howl split the peaceful Duncade air, and the unfortunate animal set off like a bullet, in search of fresh water.

Babe started to follow him, but paused. She bent to pick up the doll, casting an accusing eye skywards.

Benny whipped back his head, wishing his heart wouldn’t beat so loudly. You never know what sort of powers these culchie pixies might have. When he finally allowed himself to sneak a peek, the girl was nowhere to be seen. Doubtless off to find her distressed pet.

Benny grinned. There’s no revenge like anonymous revenge. It was well worth an old bit of plastic to see that mutt getting a slime bath. Poor old Major Action. Lost in the line of duty.

He trotted over to the rooftop doorway. Babe Meara would be investigating the scene of the crime as soon as Conger managed to scrape his tongue on some rock. He had no intention of being here when she returned to transform the culprit into a toad. Whistling merrily, Benny danced down the spiral staircase. He was getting too old to be playing with dolls anyway.

Another favourite pastime in Duncade was fishing for crawlies. These were the pygmy versions of the cruel clawed crabs that scurried along the sea bed in deep water. Traditionally, crawlie fishing was the jurisdiction of the under tens, but once again, in his loneliness, Benny was regressing to the activities of summers gone by.

First you chipped a barnacle off the rocks with your knife. Then you prised the unfortunate crustacean out of his house, pale flesh contracting between your fingers. Benny used to have nightmares about the ritual, imagining high-pitched screams of anguish emitting from the shellfish. But after the violence of playing against Enniscorthy CBS, this was small potatoes.

You skewered the barnacle with a thrupenny barbed hook, and lowered him, still squirming, into the dock. Charming. Benny had used the same line since Granda had given it to him nearly a decade ago. Ten-pound-strain catgut, with a streaky marble weight. Benny was convinced it was the stone that brought him luck. An almost perfect sphere with a hole clean through the centre. Very rare. Granda said he’d got it out of the belly of a tiger shark in the South China Sea. He explained how the stomach acid had burnt away the soft rock. It was a deadly story, so Benny decided to believe it.

Of course, being a teenager, Benny couldn’t just stroll on to the slipway and lower his line in broad daylight. Certainly not. He might as well suck a dummy and wear a dribbler. No. Much like the action figure experiments, this had to be a covert operation.

Late that evening, under cover of darkness, Benny loaded up with tackle and headed over to the inside dock. The slip was deserted, all rugrats long since consigned to their little beds. The tide was about half in, still well below the slime line.

Tausende von E-Books und Hörbücher

Ihre Zahl wächst ständig und Sie haben eine Fixpreisgarantie.

Sie haben über uns geschrieben: