Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Penned in the Margins

- Kategorie: Poesie und Drama

- Sprache: Englisch

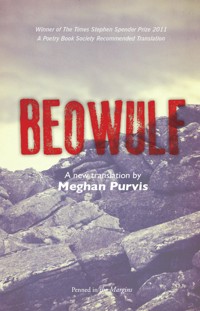

PBS Recommended Translation for Spring 2013 The Anglo-Saxon epic poem Beowulf is brought to life by American poet Meghan Purvis in a vigorous contemporary translation. Written across a range of poetic forms and voices, this rendering captures the thrust and gore of battle, the sinister fens and moorlands of Dark Age Denmark, and the treasures and glories of the mead-hall. But can the hero defeat his blood-thirsty foes, save the Geats from being wiped off the map, and claim his just rewards? Combining faithful translation with innovative re-workings and poems from alternative viewpoints, Purvis has created an exciting new interpretation of Beowulf – full of verve and the bristle of language. Meghan Purvis received her MA and PhD in Creative Writing from UEA. Her work has appeared in publications such as The Rialto, The Frogmore Papers and Magma. She won the 2011 Times Stephen Spender Prize for an excerpt from her translation of Beowulf; another poem was commended. She lives in Cambridge.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 83

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2021

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Beowulf

Meghan Purvis received her MA in creative writing from the University of East Anglia in 2006, where she is currently finishing her PhD. Her work has appeared in publications such as The Rialto, The Frogmore Papers and Magma. She won the 2011 Times Stephen Spender Prize for an excerpt from her translation of Beowulf; another poem was commended. She lives in Cambridge.

PUBLISHEDBYPENNEDINTHEMARGINS

Toynbee Studios, 28 Commercial Street, London E1 6AB

www.pennedinthemargins.co.uk

All rights reserved

© Meghan Purvis 2013

The right of Meghan Purvis to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with Section 77 of the Copyright, Designs and Patent Act 1988.

This book is in copyright. Subject to statutory exception and to provisions of relevant collective licensing agreements, no reproduction of any part may take place without the written permission of Penned in the Margins.

First published 2013

Printed in the United Kingdom by Bell & Bain Ltd.

ISBN

978-1-908058-14-0

ePub ISBN 978-1-913850-00-5

This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, re-sold, hired out, or otherwise circulated without the publisher’s prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

More than anything, this is an acknowledgement of the teachers who shaped me as a writer: Patrick Farley and Bob Jost at Manchester G.A.T.E.; Steven Roesch and Jim Davis at Edison High School; Professors David Walker, David Young, Ronald Kahn, Dan Chaon, and Jennifer Bryan at Oberlin College; and Denise Riley, George Szirtes, and Professors Jean Boase-Beier and Clive Scott at the University of East Anglia. They made me a poet, and I am deeply in debt to them all.

I also want to thank the other writers I know who spent time workshopping, supporting, and kicking me along: Agnes Lehoczky, Amaan Hyder, Anna Selby, Benjamin Thompson, Hannah Jane Walker, Hayley Buckland, Hayley Green, James Brookes, Lev Rosen, Nathan Hamilton, Sarah Hesketh and Stephanie Garbutt. Special thanks to James Jarrett, who went to see the 2007 CGI film version of Beowulf at my request and still, for some reason, continues to acknowledge me in public. I would also like to thank Libby Morgan and the 2nd Air Division Memorial Library in Norwich, as well as Robina Pelham Burn and the Stephen Spender Trust. Both of them, in different ways, provided me with time and space to finish this translation, and it would not exist without them. Thanks also are due to Tom Chivers at Penned in the Margins, for his endless support and editing prowess.

And, finally, thanks to Heather Marzette Garner, Tiffani Marzette and the rest of their family; Mary and Rob Roellke and their family; and mine: my parents Jeffrey and Susan, my sisters Dara and Ellen, my brother-in-law Jeffrey Watts and my husband Luke Jefferson. Someday, I promise, I will stop talking about broadswords. Today is not that day.

PREFACE

I was in my third year of university when the professor of my History of the English Language class stood up at the front of the lecture hall and recited the opening of English’s first epic poem. The hair on the back of my neck stood up —

Hwæt! We Gardena in geardagum,

þeodcyninga, þrym gefrunon,

hu ða æþelingas ellen fremedon.

Not because of the language, although Old English does beat out a rhythm that makes one’s hands itch for a pair of oars. Not because of the story — although, having read Seamus Heaney’s translation the year before, I was aware of the power of this story of a hero’s journey to do battle with something that changes them forever. It was because the class was taught by Professor Jennifer Bryan, and it was the first time I’d heard Old English spoken by a woman.

There were, of course, women already working with Old English and Old Norse: Marijane Osborn in America, Heather O’Donoghue in the United Kingdom, and others. But to a young woman still in university — even a good university, even one that often paid particular attention to under-represented voices — the idea that Beowulf was a story I could tell was a new horizon beckoning.

I realised later that Beowulf tends to attract translators who do not have their papers in order. Edwin Morgan was Scottish; Kevin Crossley-Holland discovered Anglo-Saxon literature after failing his first exams at Oxford; Heaney famously put a bawn, a symbol of Anglo-Irish oppression, into his rendering. My translation comes from writing as a woman — usually destined to pour mead and wait for the family feud to erupt — and as an American. We have, all of us, snuck up to this poem while the gatekeepers were otherwise occupied. None of us came to this by birthright.

And in doing this we follow our source material entirely. Scyld Scefing was a foundling who rose to become a legendary king. Beowulf was never meant to rule: he fell into it by outliving everyone else in line for the throne. The world of the poem is populated by people meant for other things, and who wanted something different. They went looking, and found lives marked out by a beating poetic line. But they, the characters, and we, the translators, also brought things with us in our boats: a way of thinking about a building with sentry towers, a name of a Norse god, a sympathy for the women left to ferry pitchers.

My translation does some things with Beowulf that differ dramatically from the source text, most particularly in my approach to the structure: I have split the poem up into a collection-length series of poems that tell the story. By doing so, my translation makes space for the many voices within Beowulf that are often drowned out by a single narrator describing a single hero. This story is about Beowulf, yes; but it is also about the narrator of the poem, and about Modthryth and Hildeburh, about Grendel’s mother, forever nameless. I have not given her a name, but I have given her and others more of a presence and, occasionally, a voice in the poem. Some people will say the shifts in focus and form I have made mean that this is not a translation. But my approach, like every approach to Beowulf, is still real; each is just as accurate as another, because translation happens in the space between, in what is passed over and what is held up to the light. Professor Bryan may have been telling a slightly different slant, but I listened, and now, over ten years later, I am telling my story of Beowulf.

I can’t tell you what you will find in this poem. I can tell you what I’ve seen: boats splitting water, an arm underneath an ashen shield, something stirring in the night. All of it is true. But what you will hear — what Beowulf will show you, will lean to whisper in your ear — is something belonging only to you. Listen. You haven’t heard this one before.

For my parents, Jeffrey and Susan,

for my sisters, Dara and Ellen,

and for my husband Luke:

for everything.

Beowulf

Prologue

HWÆT

Stop me

if you’ve heard this one before: the lands up north,

hoar-bent, frost-locked, need deeper plows

to dig them. Here is one.

SCYLD SCEFING

This is a story about coming and going. This is a story about the sea.

SCYLD came in with the first morning tide, lightly carried

in spite of the treasures in his boat — mailcoats, gold, gifts

the color of water at dawn — rich omens, indeed,

for a baby still too weak to close a fist. At that age,

all palms lie open — an orphan’s, a foundling’s or a king’s.

In time, his hand hardened into one we knelt to as king —

all of us; from the ocean he came in on to the farther sea.

I was gathering kelp when we found him, my back unbent by age,

holding his squalling face in the hollow of my neck as we carried

him to the hall, that first grey morning. I was repaid for that deed —

a small one, but one he was grateful for, if this lifetime of gifts

is any indication. We were lordless, in need, and he was a gifted

child — he took to his role of foster-lord, of king-in-training,

easily. Eager to have what was his, deeds

came quickly — he knew his way with a sword in his hand, a seabird

catching that first smell of salt. As his shoulders widened to carry

them, more and more retainers came — he marked his age

in men, not years; a loadbearer in a burdensome age.

Some he won over with gold, tracts of land gift-wrapped

in rainfall that followed the line of his eye. Some lay still, carried

off the field, the first and last tithing for a king.

I saw lifetimes of conquering and harvest, things I will not see

again. We have diminished, we are fallen — my one true deed,

performed again, taking him back to the grey death

he came from. He died in his sleep, of old age —

his grip on the pommel finally slipping, back to the sea,

back to a wooden boat — I carved the nails — and the gifts

we shroud him with. Gifts for a king, more than kingly,

gold he couldn’t at his strongest height have carried —

And let them go, past the sightline of mist, let the sea carry

his gold, his body, and his boat — wherever it may, indeed,

to whatever shining demons, whatever black-hooded kings

may care to take my people’s tithing for an age

we had no right to. Finally, my strength and my will gives —