Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Influx Press

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

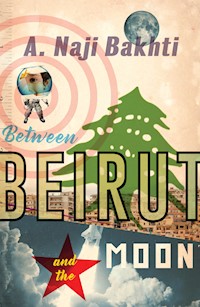

'A joyous tale from a fresh new voice.' – Cosmopolitan – Cosmopolitan A young boy comes of age within the confines of post-civil-war Beirut, with conflict, and comedy lurking round every corner. Adam dreams of becoming an astronaut but who has ever heard of an Arab on the moon? He battles with his father, a book-hoarding journalist with a penchant for writing eulogies, his closest friend, Basil, a Druze who is said to worship goats and believe in reincarnation, and a host of other misfits and miscreants in a city attempting recover from years of political and military violence. Adam's youth oscillates from laugh out loud escapades, to near death encounters, as he struggles to understand the turbulent and elusive city he calls home. ''Set amidst the country's sectarian divisions as it attempts to recover from decades of political violence and civil war, Between Beirut and the Moon charts a young boy's near-death encounters, with a colourful cast and comical escapades. A unique debut.' – AnOther Magazine

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 401

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2020

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

2

BETWEEN BEIRUT AND THE MOON

A. Naji Bakhti

5

For my mother and father

6

CONTENTS

BETWEEN BEIRUT AND THE MOON

I heard this theory once that if you toss a newborn into a swimming pool he’ll come out the other side kicking. I find that highly improbable. My father, or so I believe, has always been a strong advocate of the theory. Instead of water, however, he chose books. And instead of infants, he chose the entirety of his son’s and daughter’s combined childhoods. In more than one sense, my sister and I have been kicking through books for most of our lives. The idea was that if you expose a child to literature long and hard enough, he’ll grow up wanting to be a writer, a critic, an editor or the J.R.R. Tolkien Professor of English Literature and Language at the University of Oxford. Of course, I wanted to be an astronaut. 8

‘Don’t be ridiculous,’ he’d say, ‘who ever heard of an Arab on the moon?’

‘I’ll be the first one,’ I replied at once, instead of taking the usual route of trying to look as non-ridiculous as possible, for my father’s liking.

‘You’re flat-footed. They don’t allow flat-footed Arabs on the moon,’ he remarked casually, his face hidden behind this morning’s An-Nahar Daily, ‘it’s illegal.’

‘Who said?’

‘Jesus-Mohammad-Christ said, that’s who.’

That was another thing my father would say with unerring regularity. As if Jesus’ middle name had always been Mohammad and everyone in the world had thus far simply failed to spot this most obvious truth. One expected nothing less of a Muslim man who had forged an unholy alliance with a Christian woman against the wishes of his now irritated family and his now pissed-off god, whom, one would have thought, must have known in advance and ought to have had ample time to cope.

‘How many times have I told you not to dash your son’s dreams?’ my mother cautioned, as she made her way towards the balcony, cigarette in mouth and all. She was being generous today. Usually, she would spend most of her leisure time in the living room creating a cloud of smoke in front of her and then struggling to make out the images being displayed on the TV. ‘He can do anything he sets his mind to.’

‘Next you’ll be telling him he can walk on water. God knows we have a hard enough time getting from one country to another without being held back for a cavity search. They’ll shove a fucking Hubble telescope, mother 9and father, up his backside before they let him get on that space shuttle,’ he said.

‘Mother and father’ is a colloquial term used in Lebanon to express the idea of something whole or complete. For instance, the weight of the explosion knocked the man, mother and father, right out of the window, as men in Beirut occasionally are; or the building collapsed, mother and father, to the ground, as buildings in Beirut occasionally do.10

A LESSON IN BUDDHISM

When, in school, I was grilled on the subject of my religion by my classmates, I would respond with a shrug as bewildering to my inquisitors as it was to me. I knew that church was for Christians and mosque for MusliMs I knew this because both Christian and church begin with the letters ‘C’ and ‘H’, and because both Muslim and mosque begin with the letters ‘M’ and ‘O’, if you should choose to spell Moslem as such, but don’t. I knew that the mosque was the one that smelt of feet on any given day, but particularly on Friday; and not nice nail-polished lady feet either, but thick-skinned and hairy man feet. I knew this because my friend, Mohammad, was Muslim and he smelt of feet on any given day, but particularly on Friday.

Mohammad had devised a game, or so he told us. He hadn’t. All he had done was learn it off of his big brother.11

‘Christian or Muslim?’ he asked one day during break, extending two clenched and clammy fists and imploring me to pick one.

I picked Muslim because, in Arabic, it means peace and, I reasoned, no harm could come of peace. The Arabic word for Christian bore an uncomfortable resemblance to the Arabic word for crocodile, and I was not especially fond of crocodiles at the time.

Mohammad slapped me straight across my left cheek with his clammy right hand and ran. He hid behind the teacher’s desk for what seemed like more than ten minutes and I eventually gave up looking for him and forgave him instead. The next day I asked him where he was all afternoon and he said he was hiding behind the teacher’s desk for the first ten minutes and had since then found his mother, walked home with her, done his homework, watched Boy Meets World, went to sleep, woke up, brushed his teeth, skipped breakfast and walked straight to school.

‘Nothing,’ he said, before reciting the above activities to me in that same order.

From a distance I observed as Mohammad extended his still clammy fists to an older boy whom I had only known by name. Mohammad then struck the older boy, Boulos, across his right cheek. Boulos made an instinctive gesture as if to react. His arm was half-raised and in pole position to strike when he slowly and gradually began to lower it.

‘You’re Christian, Boulos. You can’t slap back. You see. Those are the rules of the game,’ said Mohammad, smiling triumphantly. ‘I know it’s not fair,’ he continued, ‘don’t blame me. Take it up with your own god.’12

It was true that my mother had never made to slap me across the face, nor had my father for that matter, but it was also true that the sole of her shoe had narrowly missed the tip of my nose and the top of my head on countless different occasions. Of course, on these occasions the sole of my mother’s shoe had long since left my mother’s foot and was making its own pilgrimage from her hand to whichever part of my body it had set out to reach. My mother may have been Christian but her shoe, almost definitely, was not Christian.

‘Am I Muslim or Christian?’ I asked my Christian mother over dinner. The family had been sitting before the TV set, each with a tray on his or her lap, for at least half an hour watching my father’s favourite Comedy Sketch programme: Basmeet ElWatan, which literally translates to ‘The Death of a Nation’, or alternatively, ‘The Smiles of a Nation’, depending on the manner in which one chooses to read the title. The TV set was old with vinyl wood varnish and knobs rather than buttons and my little sister’s nimble fingers rather than a remote control. The story which my parents had upheld thus far was that either my sister or I had hidden the remote control somewhere within the house when we were very young and forgotten about it. They had searched for the remote countless times before, of course, and were eventually forced to concede that it was lost forever. We, my sister and I, had to pay the price for our mistake by getting up to change the channel every time one of our parents decided they didn’t like the programme they were watching. As I was almost twice my sister’s age at the time, it often fell to her to change the channel.

‘Technically, neither,’ my father replied absent-mindedly, drawing a stern look from my mother and failing to notice both her stern look and my concerned expression.13

‘Both, Adam,’ my mother said, seeking to reassure me in some way.

‘Yes, but if I had to pick one, which would it be?’ I asked again.

‘I heard Buddism is alright. Try that,’ my father said, smiling and winking to himself.

‘How many times have I told you not to confuse your son?’ my mother remarked.

‘I’m only laying out his options in front of him, darling,’ he replied.

The conversation then went in the direction of Buddhism and how they, the Buddhists, worship a short, fat and bald man, who looked remarkably like my uncle Gamal and who had spent most of his days naked and attempting to lift himself off the ground without the effort of moving his legs. He sounded, to me, like a more obese version of Jesus but without the long and fair hair and the glimmering blue eyes.

‘Glimmering blue eyes? Where do you think Jesus was born? Sweden?’ my father interjected, now turning his attention away from the TV set for the first time in the conversation.

‘Australia,’ my sister replied with an air of authority which belied her tender age of six.

‘Why Australia, Fara?’ my father asked tugging at one of her ponytails playfully. Only my father called my sister ‘Fara’. It means mouse.

‘Why not?’ she said, adjusting her ponytail.

The general consensus was that, as God would not have consciously and willingly overseen the evolution of the kangaroo, he must’ve turned his back on Australia for a good few thousand years and so could not have sent his own son to that overgrown island two thousand or so years ago. 14The only link my sister and I could find between Jesus and Australia, years later, would be Mel Gibson, an Australian actor and director, who directed the movie Passion of the Christ. My sister maintains, to this day, that her answer was prophetic.

‘He was born in the Middle East. He was probably tanned, had a long black beard, thick black eyebrows and dark black eyes,’ my father said, running his thumb and index finger over his thick, black moustache, ‘like bin Laden.’

A week or so later, as he dropped me off to school, my father leaned over and explained that there were quite a few advantages to being a child of a ‘mixed marriage’, chief among them the ability to switch back and forth between both religions at one’s own convenience. By that point, Mohammad’s game had spread and most children, Muslim and Christian, had been slapped across their cheek at least once. Whenever we saw two of our classmates chasing one another during recess we knew that they were both Muslim and that the one being chased had just slapped his chaser straight across the face. The Christian boys, as you would expect, did not like this game very much, but none of them slapped back or chased their aggressor because they were Christian and Christians must turn the other cheek, or so Mohammad, and countless other Muslim boys, had told them.

‘I want to play again,’ I told Mohammad, who shrugged his shoulders and extended his arms to reveal both his clenched and clammy fists.

‘Muslim or Christian?’

‘Christian,’ I said smiling.

‘I thought you said you were Muslim.’ 15

‘I did. But I changed my mind. My mum’s Christian. I can do that,’ I replied, victoriously.

Mohammad slapped me across the face and stood there laughing with four or five other Muslim boys, all of whom had latched themselves onto Mohammad ever since he’d introduced his now popular game to the playground. I did not wait for Mohammad to finish his laugh before reaching over and slapping him with the back of my hand across his right cheek as hard as I could.

‘That’s not how it works,’ he said. ‘You’re Christian, you can’t slap back. Ask your god.’

I asked him, I thought, and he said it’s fine by him if I go back to being a Muslim for the next few minutes. But I didn’t say it. I didn’t say anything. I slapped Mohammad again and again. The fourth slap knocked him off his feet. He made a helpless effort to punch back as he fell to the floor, swinging his fist in the general direction of my face. I pinned him to the floor and began to punch his face wildly. I imagined that he was an alien life form which I had come across in one of my journeys to outer space, whose sole aim was to spread a disease that would divide the entire human race into tiny little groups of men and women who fought endlessly amongst themselves and achieved progress only sporadically. None of his newly acquired friends came to his aid and they were joined by more spectators, mostly young Christian boys who were led to the scene by the mere smell of retribution.

As I sat there in the principal’s office thinking about what I’d done, my mother and father were escorted to the leather chairs either side of the one I had been occupying for the best part of an hour. 16

‘Sit, they’re not just for decoration, you know,’ the principal, Ms Iman, said, tapping one of the leather chairs on its back and looking up at my father.

My father does not take too kindly to being told what to do by anyone, especially marginally younger women, and would likely have been much more cooperative throughout the remainder of the meeting had she, the principal, politely asked him to please take a seat without tapping any one of the leather chairs on the back and without making a remark about their function in an office. I was glad she had done both.

‘Are you happy about what you’ve done, Adam?’ asked the principal, leaning forward and staring me intently in the eye.

She was one of those women who had once been startlingly beautiful but who’d since deliberately taken the decision to cut her hair short, develop myopia and age a few years in order to be taken more seriously by her male colleagues.

‘Yes,’ I replied, knowing that it was perhaps not the answer she was looking for.

‘You see, the boy shows no remorse,’ she said, addressing my parents and filling them in on the details of the incident.

‘It seems to me that my son was involved in a fight with another boy. Now where is that other boy?’ my father inquired.

‘Your son broke his nose. He’s in the hospital,’ she replied, raising her right eyebrow.

‘That hardly seems fair.’

‘What, that your son broke the boy’s nose? Or that the boy is receiving medical treatment at the hospital?’

‘My son’s arms are covered with little scratches which, clearly, have been left unattended,’ my father said, putting 17both his hands on the desk before him and adjusting his seating position. ‘This boy fights like a little girl.’

I chuckled and received a stern look from both my mother and the principal, who evidently thought that my father’s remark was neither funny nor was I entitled to laugh at it. I looked at my arm and noticed the tiny scratches for the first time. They hurt more now that I was aware of them. A tear must’ve escaped me as both of their expressions soon softened.

‘What do you want to be when you grow up?’ the principal asked, looking straight at me.

Ms Iman’s what-do-you-want-to-be-when-you-grow-up lecture was infamous throughout the school. There was not a student summoned into her office who had not been on the receiving end of one. It went something like this: what do you want to be when you grow up? A doctor/ engineer/ lawyer/ businessman/ teacher. And do you think doctors/ engineers/ lawyers/ businessmen/teachers punch one another in the face? No. Exactly, now apologise to your classmate.

To say that it is inherently flawed is an understatement. That the moral fibre of a human being is essentially tied to his occupation is ridiculous. Even as eleven-year-olds, we were well aware of that.

‘An astronaut,’ I replied.

‘An astronaut?’ she repeated, turning over to look at my mother who shrugged her shoulders and smiled politely. ‘Whoever heard of an Arab on the moon?’

Out of the corner of my eye, I saw my father slap his forehead audibly with the palm of his right hand, then slap his right hand with the palm of his left one.18

‘The point is you shouldn’t resort to violence every time someone insults your religion. It’s why the entire country has gone to the dogs. Is that clear?’ asked the principal.

‘Yes, Ms Iman,’ I replied, occupying myself with the elaborate pattern of the Persian carpet on the floor.

‘Hold on. You’ve had a student spreading sectarianism around the school for the past month and you’re concerned that my son has found an unorthodox way of putting an end to it?’ my father asked.

‘Unorthodox? It’s completely orthodox, Mr Najjar, that’s the problem,’ she said, somewhat impatiently, ‘this is not the first time your son has been involved in acts of indiscipline, or blasphemy for that matter. Just last week, he asked the Civic Studies teacher whether Jesus Christ existed in the same way that Santa Claus did.’

‘Well, with all due respect Ms Iman, what the hell was Jesus Christ doing in a Civic Studies class at a secular school anyway?’ my father asked.

‘Calm down,’ my mother said, nudging her husband in the ribs.

‘And a month or so ago – tell your father what you said about the Prophet,’ she demanded, addressing me and completely ignoring my father’s question.

‘I asked the Arabic teacher whether, after commanding Mohammad to read, God then smacked him on the back of the head with the Koran, like you did to me with Oliver Twist,’ I said, staring bluntly at my father.

‘In all honesty, son, if Mohammad was anything like you, then God must’ve done, yes,’ he replied.

‘I will not have blasphemy in my office,’ said Ms Iman.19

‘Do you know who I am, Ms Iman?’ My father had just invoked the quintessential Lebanese statement which often preceded an indisputable declaration of war between two mostly rational adults.

It doesn’t matter if you’re a second-rate citizen living from pay cheque to pay cheque, with a modest background, no ancestors to speak of and earning barely enough money to feed your eight hungry children, in Lebanon you will ask this question of anyone who rubs you the wrong way and wait for them to ask you it back.

‘Do you know who I am, Mr Najjar?’

Of course, neither of them knew who the other really was. Neither of them really cared to find out. My mother, suspecting as much, stood up, apologised to Ms Iman, told her that I would be severely punished at home and asked for Mohammad’s mother’s phone number so that she may call her and apologise personally. I don’t know what my mother said, but I never heard from Mohammad or his mother again.

When we got home my parents sent me straight to my room to think about what I’d done. A few minutes later my father opened my bedroom door, walked in, and locked it behind him.

‘Your mother and I agreed that the only way to punish you is this,’ he said, holding his black leather belt in his right hand.

‘But I didn’t,’ I began to object and stopped as soon as I saw my father’s index finger being placed firmly on his lips.

‘Jump and scream,’ he whispered, deliberately missing me and landing hard lashes on the bedsheets.

‘Never be afraid to fight for what you believe in, or defend those with less courage or intellect than yourself,’ my father said, lashing furiously at the bed, ‘but always stop 20short of breaking your opponent’s nose. You know you’ve gone astray – scream – when there’s blood involved.’

‘I’m sorry,’ I said, bouncing as high as I could and screaming over his words.

‘Stop that’s enough, stop,’ my mother implored, banging on the bedroom door.

‘Do not hesitate to blaspheme if religion happens to stand in the way of truth or knowledge, but do not do so intentionally to provoke others,’ he continued, inciting me to shout louder with his left hand, ‘apologise – louder – to those whom you have wronged, but never wait long enough to be told to do it by others. It takes the gloss off of the apology.’

‘Open this door right now or so help me God, I will burst through it,’ my mother shouted.

For a moment, my father stood before me panting and trying to catch his breath; then he unlocked the door, swung it open, and walked past my mother without saying another word.

ALJAHIZ AND MONSIEUR MERMIER

Not too many men are fond of the time their father almost ended their life. It would be a sad tale to tell had my life actually ended, and I, in all likelihood, would not be the one to tell it.

Once, I asked my father if he could give me his copy of The Miserly, a book by the Arab philosopher Aljahiz, which was probably collecting dust somewhere around the house. He gave me a ten thousand lira note instead and told me to go buy my own version before hiding his head behind the An-Nahar Daily. He was looking to see if they had published the article he’d sent in the week before. Such was the chaos which engulfed the house that when my father declared a book lost, no one bothered to look for it.

All I knew about Aljahiz was that his tragic and untimely death had come about when an entire library of his own 22books fell on top of him one night and crushed him to death. It was how we’d all imagined my father would go, looking for a book to read and then suddenly being overwhelmed by a number of them launching themselves at him.

Many visitors who passed by our home on occasion, would take one glance at the piles of books stacked haphazardly around the house and put them down to my father’s insatiable thirst for knowledge. It was not, however, my father’s insatiable thirst for knowledge which cost us valuable house space, it was his insatiable thirst for books. I use the word ‘house’ loosely. Ours was not a house; it was a small apartment on the sixth floor of an old building in Ras Beirut, just off Hamra Street. The location was ideal, but the apartment itself was designed to fit one or two people at most. Certainly, not four people and an entire library.

When Monsieur Mermier, a Frenchman working for the UN, moved into the apartment facing our own on the sixth floor, my father jumped at the opportunity to invite him to our home. The Frenchman, he told me, is the pinnacle of cultured and intellectual men. Of course, he might have said the same thing about Englishmen, were we living next door to an Englishman.

‘Your home is a sanctuary for literature, Monsieur Najjar,’ said Monsieur Mermier, taking a sip of his Turkish coffee.

‘And a dumpster for everyone else,’ my mother added, offering Monsieur Mermier a tray of Arabic sweets and wiping the smile off my father’s face.

Monsieur Mermier suggested that my father should open a publishing house, since he seemed to love nothing more, on this evidence, than the sight of books stacked on top of one another. My father dismissed this without deliberation.23

After my mother went to sleep, my father took out a bottle of Arak, a slightly stronger version of vodka diluted with water to be just as strong, and offered Monsieur Mermier a few shots. They drank to health and Lebanon and success and new friends and peace and old friends and peace and France and Lebanon and Charles de Gaulle and Jacques Chirac and my great-grandfather and good health and Zidane’s footballing skills and success and Barthez’s bald head and Voltaire and Monsieur Mermier’s mother and my grandmother and Lebanon.

Not long into their drinking binge, my father confessed that it was his lifelong dream to run a successful publishing house. And not long after that, it was Monsieur Mermier’s turn to confess that it was his lifelong dream to invest in a publishing house. Neither of which ever materialised.

Despite him getting along well with my father, I was always mildly suspicious of Monsieur Mermier. For instance, he would regularly sit with one thigh resting completely over the other; it was a manner in which I had never seen a man sit before. Most men I knew, including my father, would place one ankle over their knee and sometimes hold it there with their hands. His unusual seating disposition led me to one of two conclusions: either Frenchmen do not have genitals or, more likely, evolution has exclusively granted them the ability to suck their genitals inward, whenever they so choose. Also, he called me ‘le petit prince’ which I did not like.

By the time I was five, I had grown accustomed to leaping over piles of books to get from one room to the other. Later, I stopped leaping and simply walked over the books as if they were part of the floor, infinite little rectangular tiles each with its own design forming some random grand pattern 24which made sense only to my father. During my adolescent years, I developed the much more pronounced technique of kicking through the books and landing them halfway across the apartment.

Two large ‘towering blocks of literature’, as my father often referred to them inspired by Mr Mermier’s comments, stood on either side of the apartment door as you walked in. Occasionally, I would stack the books on the floor over one another in such a way as to emulate a spaceship and pretend I was on my way to the moon. My sister would join in by spreading her little body across the floor and pretending to be a star, with ponytails.

‘Grow up,’ my father would say every time he passed by my spaceship, which is why I never got to the moon before bed.

Beside the kitchen, there was an entire room which no one apart from the members of my family had ever seen. It consisted of nothing but layer upon layer of old books, which presumably my father had once read. It was locked for most of the time anyway and my father carried the key around in his pocket. Whenever my father wished to find a book which he suspected was inside the room, he would hand my five-or-six-year-old sister a flashlight and toss her inside. For the most part, she enjoyed the task until she came across a dead cockroach, or worse, a living one, at which point she would begin to scream and my watchful father would reach across, grab my sister by the shirt and place her on the floor between his legs.

‘They’re harmless, Fara. They’re even smaller than you are,’ my father would say, before taking out a can of Bygone and emptying it inside the room.25

I pushed the door open one Tuesday afternoon, having just returned from school, and found my father attempting to slowly pull a single book out from underneath one of his two ‘towering blocks of literature’. The house was unusually empty as my mother and sister were not yet home. He ordered me to stand beneath one of them and support its weight while he made an attempt to withdraw the book. The moment he tugged forcefully at the book, perhaps out of frustration, both columns came tumbling over my head. Though we lived in a small apartment, the ceiling was undoubtedly high, and had one of the heavier hardcover volumes of Encyclopedia Americana fallen on my head, some serious injury might have resulted to my skull. None of them did. I would later survive two full-fledged wars and one tiny one which would last four whole days, but I consider this incident to be the most life-threatening, near-death experience I’ve ever been involved in.

I leaped and screamed and swore and cursed and was excused for all I’d done when my father saw that the books had landed on the floor and not on my head. He clutched my shoulder with one hand and kissed the top of my head twice.

‘Not a word of this to your mother,’ he said, as we picked the books up and began to stack them into two perfectly aligned columns.

THE OLDSMOBILE

Ours was an aging, white, second-hand American-made car called Barney. The night my father bought it from Payless Car Rental, he took me by the arm and told me all about how he intended to take us for a ride around Beirut in the morning. The next day, he gathered us around him, rubbed his hands together and presented us with the keys to the 1988 Oldsmobile.

My mother muttered something, put out her cigarette and left the room.

The car had been christened Barney by my sister who, having not yet seen the car, decided that it deserved a name.

My father’s choice of cars had been notoriously unpopular. His tendency to buy used cars and, in this instance, overused cars resulted not only in regular visits to the overjoyed mechanic but also the occasional car accident 27and the increasingly frequent exchange of sharp words between my mother and father. For the most part, they pretended that we could not hear them in the back and, for the most part, we were glad to pretend that we could not. My sister, who at five was not as keen an observer of our silent agreement with our parents, would now and then stick her head in between the front seats in order to adjust the air conditioning or the radio, at which point my parents would briefly fall silent. They would resume only after the last of my sister’s ponytail had withdrawn itself.

The neighbours did not like our car because it was too big and it took up too much parking space. My mother did not like it because it was white and would get dirty far too easily, and because my father had bought it without first discussing the matter with her. My sister did not like it because it was infested with little cockroaches that would, frequently, climb up her own little legs, and because it seemed to trigger an argument between my mother and father every time they set foot inside. My grandfather did not like it because the only thing worse than an American-made car is a second-hand American-made car and because he had explicitly advised my father not to buy this second-hand American-made car. My father, and the mechanic, were very fond of it.

Whenever my father was asked what he’d seen in this overgrown excuse for a car, he would inevitably ramble on about luxury.

‘It’s like driving a limousine,’ my father would say, until my grandfather informed him that driving your own limousine was very much missing the point of owning one.

It was not long before my father came to view the car as an extension to our home. Soon my sister and I found ourselves 28sharing the back seat with all manner of paperback and hardcover books each seemingly intent on making it their own with little regard for leg space. The greyish cloth which had served to cover the inner ceiling of the car did so only half-heartedly, creating something of an air pocket between itself and the ceiling, and now hung low enough to scrape the head of almost anyone insisting upon sitting fully upright. The remaining side-view mirror was soon knocked off by a speeding motorcyclist and the rear-view mirror by my father’s angry swipe at it. Driving Barney, as a result, involved an active effort on my sister’s part, who would sit on top of a stack of books, with her back to my father, and inform him of oncoming cars when the occasion called for it. During the months of the winter, water from the rain would find its way through the cracks and seep into the seats. The smell of wet, crumpled old newspapers, which we often placed between ourselves and the damp seats, coupled with that of the seats themselves, and the equally damp books, became a constant over the brief but full life of Barney the car.

Every Sunday my father would pack us all, my mother, my sister, myself and the damp literature, into the car and drive us to his father’s house. On the way there, to distract us from the challenges of the car ride, my father would tell us stories about Bilyasho, which is Italian for ‘clown’ and is spelt: pagliaccio. Bilyasho was a character who also featured heavily in the bedtime stories my father used to tell us. Bilyasho would get himself into all sorts of trouble, and then get himself out of it by some happenstance. He never meant anyone any harm, but he always brought it upon those closest to him. All the other characters admonished Bilyasho at the end of each story but then they forgave him and laughed about his latest misdemeanour.29

My grandmother would welcome us with a smile and open arms. My grandfather with a nod. He had lost most of his hair and teeth. What little hair he did have, he would make sure to dye brown which he, to my grandmother’s amusement, insisted was his original hair colour; a habit which my father picked up in his later years. His remaining teeth too were brown. His penchant for smoking over more years than he cared to count ensured that they would remain so. My grandfather’s smiles were as sparse as his teeth and neither was a sight which I ever got used to seeing.

According to my father, the only time my grandfather is supposed to have smiled, prior to that Sunday, was when he won the lottery. My grandmother neither affirms nor denies this; nor does she claim to have seen him smile on their wedding day or on the birth of any of his ten children, especially the last one. Whenever I asked my father where all the lottery money had gone, he would shrug his shoulders and tell me to ask my grandfather. I never did.

My grandfather tells the story of how he woke up one morning with his old license plate number ingrained in his mind, how he wrote it down so as not to forget it, how he went around Beirut looking for the ticket with that same number, how he couldn’t find it, how he could not find it, how he wished he could, how he sat down at Wimpy Café on Hamra Street for a cup of lemonade with mint, how he settled for a ticket with a single digit off, how he called on Abou Talal to help carry the briefcase full of cash across Ras Beirut, how Abou Talal had advised him against withdrawing the money all at once, how he ignored him, how hot it was that day, how you could tell because of the 30large sweat stain across Abou Talal’s shirt, how humid, how like Beirut in the summer.

My father tells the story of how his father took him, the eldest, by the arm and told him all about the lottery ticket and his plan to return with a briefcase full of cash, and Abou Talal, how he was instructed not to tell anyone, how he ignored his father’s instructions at the earliest opportunity and assembled all three of his brothers and all four of his sisters and his mother, how his father opened the door to find them all awaiting his arrival, how Abou Talal wiped his forehead and how my grandfather smiled.

‘Where did all the lottery money go?’ asked my sister one Sunday, looking up at my grandfather, as my parents and I made our way past the odd collection of twenty or so assorted relatives standing up to greet us.

My grandfather smiled. My father did too. Everyone else let out a nervous laugh, or pretended not to have heard.

When he first won the lottery, An-Nahar supposedly ran an article calling him ‘the man who won whilst the nation lost’. It was the early seventies and Lebanon was on the verge of a civil war that would last for fifteen years. In that time period, my grandfather Adam travelled the world, sometimes disappearing for weeks and months on end but always returning home to his war-torn country, his faithful wife and his steadily increasing number of children. Once, after a particularly long absence, my father asked him why he’d taken so long to come back.

‘Traffic,’ answered Grandfather Adam, then he threw my young father the keys to his new Mercedes-Benz. He had driven it all the way from Frankfurt.31

In the years after the war, when Grandfather Adam’s lottery money had almost run out, he arranged to go on the holy Islamic pilgrimage to Mecca, referred to as Hajj. He had, thus far, not been particularly renowned for his religiosity; his casual approach to alcohol, bacon and extramarital sex being some of several reasons why he was not. Grandfather Adam never divulged his motives behind that trip, or any other. My father mused, years later at the funeral, that it was a result of some misplaced urge to express gratitude to someone for those fifteen or so years of joy. It was not lost on my father that gambling too, of which the lottery is a variation, is forbidden in Islam.

Upon returning from Hajj with a black eye, my grandfather is said to have serenaded everyone who had come to congratulate him on a successful pilgrimage with the tale of how he had been involved in a fight at the Stoning of the Devil ritual. A man had stoned him instead of the devil and he had stoned back. It was one of those rare occasions in which he had opened up about his travels at all.

‘Where?’ my sister asked again, still staring at him.

‘Everywhere,’ my grandfather said, leaning over to the sound of a much quieter room.

He placed both his hands on my sister’s shoulders and told her – for what must have been the ninety-second time – the story of how he woke up one morning with his old license plate number ingrained in his mind, how he wrote it down so as not to forget it, how he went around Beirut looking for the ticket with that same number, how he couldn’t find it, how he wished he could, how he could not find it, how he wished he could, how he sat down at Wimpy Café on Hamra Street for a cup of lemonade with mint, 32how he settled for a ticket with a single digit off, how he called on Abou Talal to help carry the briefcase full of cash across Ras Beirut, how Abou Talal had advised him against withdrawing the money all at once, how he ignored him, how hot it was that day, how he could tell because of the large sweat stain across Abou Talal’s shirt, how humid, how like Beirut in the summer.

‘And then?’

And then he told her about how, on his way back with Abou Talal, he had been ambushed by two Christian militiamen who demanded the briefcase, how he had been forced to fling the briefcase as far and as high as he could while he held them off, how the briefcase had burst open in the air, how random people on the street had danced to the tune of paper falling from the sky and how, for a brief moment, it was raining liras on Hamra Street.

When the story was over my grandmother had her head in her hands and my mother was standing over my sister with an arm around her. My father looked at me and shrugged his shoulders. These were fabrications, he knew. But he would not stop my grandfather in full flow.

‘Go into the bedroom, and let the adults talk,’ my father said, ‘all of you.’

He meant the kids. Including myself, my sister and twelve or so of my forty-two cousins who happened to be present on the day, no doubt also dragged to the congregation by their parents. The teenagers hung out in one corner of my father’s old bedroom, and mostly ignored us. The twenty-somethings were not really kids but they too were happy to vacate the living room upon my father’s command. They lingered by the door. Looking back, I sometimes think it 33was a consciously symbolic gesture, an affirmation of their status as those to whom adulthood was just beyond the threshold of my father’s old bedroom door. But we were kids and I suspect that it was more an expression of their dominion over the younger ones: us. They kept peering into the bedroom and rarely poked their head outside to see if the atmosphere was ripe for an induction into adulthood. Only the toddlers ignored my father, mostly because they could not understand him, or anyone for that matter, but also because there were no consequences to their actions. They picked their noses or made funny little noises, they clapped their hands together or cried or crawled around on the ground between this uncle’s legs or past that aunt’s pointy heels.

The rest of us occupied the bed. We were the youngest of the bunch in my father’s old bedroom, but we were the loudest and most comfortable around a bed. This subgroup of cousins included my Aunt Sonia’s two younger girls, Yara and Lara, and my Uncle Gamal’s eldest daughter, Ferial. We were all about the same age, apart from my sister.

Yara crawled towards the centre of the bed. She craned her neck, surveying the room with caution before leaning in my direction.

‘You know that it’s made-up nonsense, don’t you?’ said Yara.

‘They’re stories,’ said Lara, above her sister’s shoulder, ‘he spent all the money on alcohol and traveling around the world. He wasn’t robbed. It never rained Liras on Hamra Street.’

‘I don’t believe you,’ said my sister, who sat so close to the edge of the bed that when she spoke the sheer force of her words almost knocked her onto the floor.34

‘Suit yourself,’ said Yara, ‘I’m telling you the truth. He did not come back permanently until he was an old man.’

‘Some say he even stole the money. Him and Abu Talal,’ said Lara. ‘Think about it. How many people actually win the lottery? What are the odds?’

‘You’re liars,’ said my sister, ‘both of you. And you’re going to hell because that is where liars belong.’

‘You know your mother is going to hell, right?’ scoffed Yara.

‘She means that in the best possible way,’ said Lara.

‘Of course,’ said Yara.

‘No, I don’t,’ I replied, ‘who said?’

‘Your mother is going to hell,’ said my sister, which is what I should have said.

‘Our mother says so, and everyone agrees,’ said Yara.

She ignored my sister because she was small and even though we were all sat on the same bed, she could easily be pushed off, and the conversation carried on without her input.

‘Why?’

‘She’s a Christian,’ Lara whispered, presumably so as not to unintentionally spread Christianity around the room.

‘I doubt it,’ I said.

‘No it’s true, I swear,’ said Yara, ‘she is a Christian.’

‘I know that. I meant I doubt that she would be sent to live in hell.’

‘You’re not sent to live in hell,’ said Lara, leaning forward and pushing her fringe back, ‘you have to die to go to hell.’

‘Why would anyone want to do that?’ asked my sister.

‘That’s a long way away,’ I said, also ignoring my sister’s words.

‘That’s what you say now,’ said Yara, ‘but life passes by in the blink of an eye.’

‘Who said?’ 35

‘My mother.’

‘Ferial agrees, don’t you Ferial?’ asked Yara.

‘It does,’ said Ferial.

Ferial was a shy girl who wore glasses and the frizzy, wild hair which so distinguished my sister, but with less character and more poise.

‘No, I meant about their mother going to hell.’

‘I am not sure about that. I mean, I don’t mean to be rude, but have you asked anyone else apart from your mother about this?’

‘It says so in the Koran,’ said Lara.

She and Yara exchanged brief glances. One of them nodded to the other.

‘Shut up. Tell them to shut up,’ said my sister, glaring at me, ‘why haven’t you told them to shut up yet?’

‘It says in the Koran that our mother is going to hell?’ I asked.

‘Not exactly.’

‘It’s implied,’ says the other one.

My sister jumped up onto the bed, now barefoot, and formed the letter ‘C’ between her thumb and index finger. She swung her hand from Yara to Lara and back again. At first, I thought that she had meant to form a hook with her index finger but had simply forgotten, or failed, to tuck her thumb in. But she hadn’t.

‘Whatever you say goes back to you,’ she said, waving the ‘C’ claw in their faces.

‘That’s ridiculous,’ said Yara or Lara.

‘Yes, look,’ said my sister, illustrating the dynamics of the gesture, ‘It flows like water under my finger then slides out my thumb and back onto you.’

‘Shut up, and sit down,’ said Lara or Yara.36

‘No,’ shouted my sister, attracting the attention of the older cousins, ‘you’re ridiculous and you shut up and your mother is going to hell. That’s how it works.’

There was audible tension in the room because now that the adults were invoked, they were bound to make an appearance at some point which would not end well for anyone caught in a compromising position in that instant.

‘That’s not how it works,’ said Yara, her voice now also raised.

‘It says so in the Koran.’

‘It does not.’

‘Tell your sister to shut up and sit down,’ said Lara.

They were both standing on the bed now, in their matching bright red shoes. Yara pushed my sister off the bed. And I stood up and pushed Yara off the bed, and then Lara for good measure. I spotted Ferial silently edging herself towards the corner of the bed and gave her a slight shove too. I felt a large hand on my shoulder. I spun around and felt the knuckles of a fist connect with my face and a throbbing below my left eye which is unusual because usually you do not feel the throbbing until after the adrenaline wears off but I did. It was Yara and Lara’s older teenage brother, Omar, who had intervened to put an end to the commotion.

‘Didn’t your mother teach you not to hit girls?’ asked Omar.

I thought about trying a funny retort to do with her being too busy planning her journey to hell, but I could not formulate the sentence fast enough – I could not decide if she was booking accommodation or already packing – and my eye was throbbing, so I just lay on the floor and avoided making eye contact. Which was also what I did when my 37father burst into his old room to find me sprawled there with my hands pressed against my eye.

‘Jesus-Mohammad-Christ,’ said my father.

He pinched the bridge of his nose then walked out without asking any questions. He muttered something to my sister about putting her shoes on.