Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The Lilliput Press

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

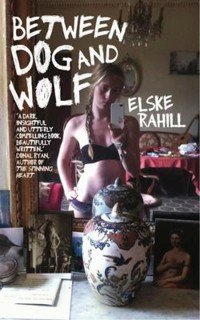

The French call it entre chien et loup . . . Darkly moving, often shocking, this interwoven story follows three college students, desperately searching for a place between the familiar and the strange as they careen towards self- knowledge. Cassandra, volatile and scarred by loss, has been sculpted by the bohemian high life and then discarded. Oisín, a country boy pulsing with sexual aggression, is prone to equal flights of rage and compassion. And you, Helen. Helen, who takes these two fractured lives and dashes them against herself, creating ripples that twist and distort their images of what should be. In this stunning debut novel, each character forces the boundaries of normality, negotiating the chasms of their own violent sexuality and decay.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 459

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2013

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

between dog and wolf

elske rahill

THE LILLIPUT PRESS

DUBLIN

For my sisters, Juliette, Felicienne, and Lydia

One must find the history of what she could not know if one is to try and recognize her. One must find the history of what she cannot narrate, the history of her muteness, if one is to recognize her. This is not to supply the key, to fill the gap, to fill the story, but to find the relevant remnants that form the broken landscape that she is.

Judith Butler, 'Bracha'sEurydice'

prologue

It doesn’t cryat all, your baby. For three days it turns in its glass box, opening and closing its fists. The fingers are pale, furling, strong as the claws of a bird. What comes from your nipples isn’t milk at all. It’s bright orange at first, then bright yellow. You taste it. You finger it into the small mouth, and the round tongue works vigorously. This is more important than the milk, the nurse says. It’s for cleaning the stomach of you; of your blood and your insides. It’s for separating the new body a little farther from your own.

You spend the third night cross-legged on the bed, rocking as the baby suckles, coaxing the milk in, touching your lips to the furred scalp. You can say it now, you think. You can tell it something true, whisper it close to the head that smells like coconuts—

—But this is notfor me to know: the smell of your own flesh that is also not yours; the aloneness of that. The first night in a hospital bed with sterilized sheets, the hours distilled in the night by the baby’s pulse and yours; as banal and momentous as waves crashing on a beach:katchoo,katchoo.The head emerging from you like a battered balloon, fingers like tentacles drinking in the light, the skull-crush opening into a face knowing and stupid like an ancient fetish.

These are your things. I must try to remember that now. It was easy to forget, Helen, with someone both evasive and penetrable, like you. I couldn’t help exploring you, creeping into your eyeball and crouching there, peering out at your world. I couldn’t help delving into your mind, that languageless lagoon, perverting it into narrative. All that I did though – speaking for you, stealing from you, creating and undoing you, I did because I loved you.

one

Helen hadher back to me. She was leaning a hip against the counter, humming, waiting for the kettle to boil. I was still warm from bed and wrapped like an invalid in layers of thermal vests. Helen’s feet were bare. It made me shiver just to see them naked like that: her toes purplish against the chequered floor. The floor must have looked like a chessboard once, but the white squares have yellowed since it was first put down, and the black ones are sun-bleached grey. There is a gap at one corner where the lino has curled up, and dust and stray peas and hairs and bits of tobacco gather under it. The kitchen is shared by six of us. Like the other kitchens on campus it’s tiny, with the drabness, outward cleanliness and inward filth of a place unloved and tended weekly by a professional. Helen bought a fish bowl to liven the place up, but the fish keep dying. There was another dead one there this morning, floating at the top with its fins clamped to its body. Helen mustn’t have noticed yet.

She was wearing a matching pyjama set of brushed cotton with heavy, straight folds at the shoulders and up the legs. She looked clean. I was very aware, suddenly, of the pockets of stink trapped against my body. When I moved a waft of stale body heat was released up and out the neck.

‘NewPJs?’ The sound of my own voice startled me. The words shot out like an accusation:NewPJs? She looked down at her body as though she had forgotten what she was wearing. The pyjamas were cream. Pink moons and stars were printed on the fabric with the words ‘Sleepy Girl’, designed to look like a child’s handwriting, floating about between them. The top buttoned up the front like a shirt, the way all pyjamas used to. It didn’t look right on an adult body. It made her breasts seem heavier than usual.

‘Penneys – seven euro –sucha bargain! They’re socomfyas well!’

I am not used to seeing Helen without make-up. All day her face is an orangey disc with shimmering lids, spider lashes, smiling mouth the colour of bubble gum. In the mornings her eyes are ringed black by the residue and a tan tidemark outlines her jaw. She must have scrubbed well last night, because this morning she had fresh, translucent skin – impossibly white. It made me think of dew. The only clues to her usual mask were the unchanging eyebrows, professionally plucked into sharp little peaks of alarm. Otherwise she looked gentle this morning, peaches-and-cream pretty. I told her she’d get a cold in her bare feet and she shrugged, sliding a big mug of tea across the Formica. She was feeling happy this morning. You can always tell how Helen is feeling at a glance. Her mind was cloudless behind her eyes.

‘You slept late. Late for you, Cass.’

I shrug. Actually, I woke quite early this morning. I watched the ceiling and thought for a long time about getting up. The white paint was splattered with grey blots. It wasn’t the first time I’d noticed them. If I stare at them for too long they begin to move about the ceiling like silver worms. Today it was worse; they merged and parted quickly, rolling into one another and multiplying like mercury maggots. It was so terrifying that I didn’t want to see. I pulled the blankets up over my head. I wanted to shrink back to the dark like a snail. In a neighbouring room someone scrambled into their clothes and clattered away, late for something, and the sounds of the college day started up outside my window. I don’t have a clock but I can count the hours from bed by the morning chats and the yelp of sneakers.

I know those noises by heart but they always shock. Their life scratches at the walls, pecking at my quietness to haul me up out of my shell.

‘I have no lectures today,’ Helen said, hoisting herself up onto the counter and kicking her heels against the press. A dimple curled at the edge of her mouth. Her hair is a mass of blonde wisps, barely believable, like the hair of something mythic.

‘I haveabsolutelynothingto do today!’

This seemed to make her proud and she hopped down again, all dimples and light. Why was she so bloody happy?

I smiled, ‘What will we have for breakfast?’

‘Dunno. I feel like Coco Pops. Do you have any? I’m totally addicted to Coco Pops at the moment. I ran out yesterday. I meant to buy more …’

‘No.’

‘Oh well. I don’t know then. I’d love a fry but I’m totally broke. I spent a fortune on Saturday night …’

‘There are eggs. Will I make us some pancakes?’

‘Oh yeah! Cool. I haven’t had pancakes in ages!’

There wasno ground coffee left in the tin, which in any case belongs to Cahill down the hall. Neither of us drinks instant, so we raided Helen’s penny jar, and she put on a coat and flip-flops and went to the snack stand in the computer block. While she was gone I mixed the eggs, sugar and flour into paste with a fork and then slowly, carefully, added the liquid; half milk, half water. The first pancake was a disaster and I had to throw it out. The rest I spread with raspberry jam and sprinkled with hot chocolate powder. They were piled on the plates by the time Helen got back with coffee in cardboard cups.

So we sit on her bed, our backs against the wall and the duvet spread across us lengthways, feet sticking out the end. These rooms were decorated when paisley was either in fashion, or cheap, or both. The sixties it must have been, but I don’t know. I’m no good at that sort of thing. I don’t know what ‘paisley’ means exactly, but I know that it describes this decor: floral print curtains, brown on lighter brown, tinged orange by years of daylight. No-colour walls. Cockroach-colour carpet. The flowers join up like spreading mould. They resemble no flower and all flowers. Helen’s room is bigger than the others. She has a dressing-table strewn with lipsticks and dusty make-up brushes. There are photographs stuck around the mirror in careful disarray. They’re the same sort of pictures she used to put up in boarding school: party scenes of people grabbing each other in elbow hugs, clutching bottles of beer. It’s her way of assuring herself that things go on outside her room, that she has fun. The room always smells like her perfume: a sweet vanilla concoction that comes in a bulbous white bottle.

She has been keeping an orphaned kitten in her room for about a week now. It mews until she lifts it onto the bed where it topples about clumsily and its tiny claws catch in the blanket, making quick, painful nicks with every move. It’s a miserable little thing. It trembles constantly. When you hold it you can feel its skeleton through the loose, blubbery skin.

Helen still hasn’t put on socks. We laugh about one of our lecturers – ‘the woman-hating, youth-crushing cat-man’, Helen calls him – who looks like a giant, bald cat, the inbred kind; pink with big ears and a pixie face. Siamese or Pekinese, Helen says they’re called. He enjoys telling us that all personal morals are a social construct. He enjoys our dismay.

‘… very juvenile for a middle-aged man.’

‘Yes but for acat…’

We guffaw like little boys and let the hot raspberry jam trickle between our fingers and plop in sticky drops onto the plates and duvet. It is only with Helen that I get like this – giddy, laughing at things that aren’t witty, nearly dribbling with stupid, clumsy laughter.

The kitten’s tail sticks up straight, quivering. Its cry is sickly and hopeless. It is very young and might not live without its mother. We can hear Cahill, the Irish language student, banging the kettle and cursing me in the kitchen. He has seen the pancake in the bin. I wrapped it in newspaper and everything, but he must have spotted it somehow. He is well brought up, raised on some Irish-speaking island, and enjoys a good earnest rant about wasting food. I often think he puts on rubber gloves and trawls through the bin, searching for evidence of my wastefulness.

He marches down the hallway and bangs on my bedroom door.

‘Cassandra?’

We pull Helen’s duvet up to our mouths to stifle the giggles.

‘He’s a total nut,’ Helen mouths, raising her eyebrows, curling her dimples.

‘Cassandra? Cassandra? Did you make pancakes?’

‘How does he know it was me?’ I whisper. For some reason this makes Helen laugh more.

‘Shhh. Sh. He’ll hear you!’

Then he’s back to the kitchen, muttering to himself as his porridge simmers.

Helen is still in hysterics, biting the duvet, tears starting in her eyes, but I don’t feel like laughing any more and it annoys me that she does.

‘Are you ever totally happy Helen?’

Before it’s out of my mouth I am embarrassed. The question hangs there. I’m not even sure what I mean. It seemed, for a moment, as though that’s what it was all about; our laughing, our eating pancakes for breakfast, that it was all about saying, ‘I amtotallyhappy.’ I got it wrong though. I can see that now. She giggles, her head thrown back in dismissal.

‘Cassy, what are you like? It’s too early for all that stuff. Drink your coffee!’

She tongues the jam out from in between her fingers and wipes her hand on the duvet. I think of the smell of dried spit. Like public phones. Like blow job.

My question must have ruined her mood because she decides to go to the library for the afternoon. At least I won’t miss that lecture now. I’ll make it up to her. We’ll go out tonight and I will be positive and fun and light-hearted. I can be like that sometimes. We’ll pick up some good-looking men, laugh at tired jokes, flirt all night and leave them at the taxi rank.

Oisín triedto re-button the three plastic poppers of his duvet cover where they had come undone during the night. Then he gave up because the duvet had twisted itself up inside and bundled to the bottom and the whole thing had to be redone.

The sight of her had affected him last night. She stayed with him like a sum or a crossword clue.

He had been coming home early from a party, tired, with a weight in his belly. He was a little too drunk to concentrate on his book and he tried to stare out at the wet, black road and the January darkness. When she stepped onto the bus with an air of summer and light about her he felt okay again. Suddenly he didn’t mind just sitting on the bus, doing nothing. Looking at her made him feel like he wasdoingsomething. He watched her put on lip gloss for no one and blink at the rain. He knew her name, Helen, although he couldn’t remember how he knew it. He didn’t say hello. He wasn’t sure whether they were supposed to recognize each other. He had nothing interesting to say anyway.

Keeping his body under the blanket, Oisín reached an arm out into the cold air and patted around the patch of floor beside his bed, feeling for his laptop. He had left it open. Grabbing the base, he heaved it up off the carpet and plonked it onto his knees. It was still on standby, hot like a hurt limb and buzzing weakly with the effort of staying alive all night. He tapped the mouse pad and it sighed, flicking the screensaver on: a picture of Kirsten Dunst wearing a pink crop top, her dimples neat as the little dent of her navel – a still from a film he hadn’t seen. Then he clicked on the internet icon and waited for the page to load.

He logged in to his email account. There were no new messages, so he browsed through his old ones and found the link he was looking for in a message from his friend, Aengus: http//www.xxccklolly//grl2grl. The link turned blue when he moved the arrow over it. He clicked and waited. A picture of two identical girls flashed up: outstretched tongues touching, hands on each other’s breasts, semen splattered on their faces and in the briny tangles of their hair. He liked when his mates from home emailed these links. It was easy to just click and not have to feel like a pervert searching for porn. You didn’t have to pay unless you wanted a video.

At home in Tipperary he hung around with the lads. They were very different from the guys in college. They sat together in silence mostly, but they understood each other, Oisín thought. When they spoke it was without eye contact. It was loud and followed by an expletive or a guffaw. They talked about what band was ‘fuckin’ crackin’ or who was doing the local ‘fox’. Occasionally they went to gigs or to the cinema together in small groups. They were all employed, after many years of resistance, in low-ranking office jobs or serving meals-on-wheels to the elderly. They were living at home as they plodded into their thirties. One of them, Aengus, had a girlfriend.

The youngest of the lads, and the only one to go to college, Oisín had long ago vowed in a wordless part of himself not to become a snob, to never consider the lads anything less than he had when they had offered the only possibility of a social life. Whenever he was really down one of them was sure to suggest a trip away. Oisín thought of these holidays as a chance to let off steam, as though there was an uncomfortable burning in him that had to be vented abroad. He usually had fun and came back refreshed, his mind clearer. The last holiday was in Amsterdam, getting so high that they kept losing their way back to the hostel, and watching live sex shows starring mysterious-looking immigrant girls.

He was surprised to discover what ‘live sex show’ really meant. The first time they went Kevin had organized the tickets. He was good at that sort of thing, and often said that if it wasn’t for him the lads would never do anything but sit on the couch all day and night, wanking and drinking beer.

‘If it wasn’t for me, fuckin’ Denis would still be a fuckin’ virgin! Wouldn’t ’cha Denny?’

‘Go ’way to fuck,’ said Denis, looking into his pint, searching for something better to say. Kevin was tall with a strong jaw. He had the best score record. If the lads were picking up women he always got the pretty one. The girl’s friend went to Aengus, or sometimes Oisín, and the rest of the lads had to peel off and find their own birds.

Kev was the one who had suggested the holiday in the first place, booked the hostel, collected the money. He was in charge. He bought the tickets to the sex show without asking anyone else. With half-hearted protests of ‘fucking rip-off’, the lads had each given him their fifty-five euro and followed him to a small brick building in the red-light district. It looked like an abandoned house. The front door was not locked. It opened inwards. Beyond the door, the building expanded like a magic wardrobe. They were in a circular lobby with a high ceiling and corridors leading off it in five directions. These corridors might lead to anywhere, thought Oisín, to more lobbies with more corridors. The building might go on and on indefinitely.

The guys waited in the lobby, kicking the carpet, trying to make jokes but too giddy to think of any. Denny, stooped and balding at the age of thirty-one, wearing a T-shirt that said ‘I fucked your girlfriend’, told Oisín about that time they had stolen the pint glasses from Nancy’s bar.

‘And Kev’s face! Man i’ was d’ funniest thing ever!’

Oisín felt sorry for Denny. He couldn’t help it. All of Denny’s stories were about ‘d’funniest thing ever’, and he had told the story of the stolen pint glasses four times since the airport yesterday. Oisín had never allowed himself pity for any of the lads before, and it felt like treachery. He didn’t know which was kinder: to slag Denny off or to laugh along. Without deciding to, he let out a deep, open-mouthed laugh that reverberated too much in the stripped room, shocking even himself. Kevin and Aengus looked at him, and then back down at their shoes. They scuffed at the worn carpet. Oisín yawned and looked at the ceiling. There was gold paint flaking off the plaster cornice.

At last a skinny usher arrived, took their tickets, told them all to follow him, and proceeded down one of the corridors. The men walked behind him in silence, falling into single file, lead by the glow of the usher’s torch down a long, low passageway. Oisín felt as though they were tunnelling down under the earth. They passed closed doors. There was felt on the walls. Oisín ran his fingers along it until the tips began to burn. His throat hurt.

They arrived in a dim room with no windows. Before leaving, the usher pointed to a small built-in bar in the corner, where an Asian girl in a trim three-piece suit offered them a choice of complementary beer or vodka.

‘Check out the cutie Korean!’ Oisín had whispered to Kev, but Kev was busy checking her out already. A red velvet curtain, rough with dust, spanned the width of the room, dividing it almost in half. Oisín thought it would pull back and reveal a large screen. He expected a gigantic woman with heaving breasts groaning and glowing out from the wall. Then music began from somewhere. It was slow electronic music, and it made him think of how the world sounds when you dunk your head under in the bath.

The curtain screeched back, wavering gracelessly and his eyes fixed immediately on the wall behind it, thirsty for the image. There was no screen. The back wall was made of fat bricks painted a thick, glossy black. He thought briefly: ‘That’s varnish paint. That’s not for walls.’ His eyes scanned down to where the performers were positioned on the maroon carpet: a man sitting on a wooden chair, his penis almost erect, a too-young girl on her knees beside him, kneading the pink blossom of his foreskin. The scene looked shabby after Oisín’s vision of monstrous breasts.

The lads walked back through the red-light district afterwards, making noise but not having conversations, hunching their shoulders, taking up space and elbowing each other when they passed a good-looking prostitute.

They were not very friendly girls. They sat on high stools, looking glum and texting on their phones. The lads mustn’t have looked like potential customers. If you showed interest though, they smiled and looked down at their own bodies as though to say ‘You want?’ Denis was gone when they reached their hostel. He appeared two hours later, claiming to have lost his way, but smirking to show that it wasn’t true. Kev slapped the back of Denny’s head, ‘Denny you poor bugger!’

‘Bugger and more,’ said Denny, ‘I’m telling ye, man! You ever get a bird like the one I just had, get back to me then!’ Oisín envied his balls. He wouldn’t have been able to do it. He would have got too excited or something.

Later, when they were alone, he asked Denny what she had been like. He told him the girls liked Irish guys. ‘They love us. Hate English lads. The English lads abuse them an’ all. Hurt them. We just ask for a bit of head and a poke. And we’re good looking. That’s what she said. Not like them English. She liked me. She likes blue eyes. Told her she was a good girl. She was a good girl …’

The lads went to a handful of sex shows after that, until they ran out of money and their week in Amsterdam was up. The last show was in the same place, but it was a different performance. The tickets said ‘Ying and Yang’.

The girls were different colours: one brown and one very white. She could have been albino if it wasn’t for the flat blue eyes. They were smiling as they licked each other, and made sounds as though they were coming. They locked eyes with each of the lads in turn as they did it, and whichever guy they were looking at said ‘Whoa baby!’ or ‘Oh yeah!Do it for Daddy!’ and things like that. Oisín hoped they wouldn’t look at him; he wouldn’t know what to say. He was semi-hard and he didn’t want it to go away but he didn’t want to get any harder either. The girls removed each other’s bras. They were flimsy, transparent things with sequins sewn onto them. The pale one had pink hair and a sequined cherry on her thong, right at the top of her ass crack. She looked him in the eye and smiled.I’m beautiful,her eyes said, but they were lying. Her eyes were jaded. She lifted her chin and nudged her lips at him, ran her tongue over her teeth:I want to lick you. She wanted him to believe that, but it wasn’t true either. There were thick red lines on her breasts.

He was getting harder despite this; a warm thrill tumbling down his spine, up through his testicles. His beer bottle was cool against his fingers, but it couldn’t soothe him. His hands were slippery. He didn’t want to look at the others to see if they were the same, and he knew they weren’t looking at him. It was a matter of respect between the lads.

He stared at the black wall. It had been painted quickly. Glossy bubbles had hardened in the valleys between the bricks. He concentrated on that and the cold glass in his grip until his erection eased.

When he looked back at the girls the dark one was bending over, groaning, while the other one held the lips open, splaying the shock of pink folds, and flicked her tongue inside. He had never had sex with a black woman. His cum would look like milk on her skin.

Pink inside. That surprised him. He would have thought purple-brown. The lovely ache in his groin made him want to keel over. He felt something terrible might happen if he didn’t reach down and grasp his cock: his whole pelvis might implode. That wordcock.He wanted the one with the pink hair to say it,cock.She might not speak English. He would teach her that word, she would look at his lips and repeat after him. ‘Cock,’she would say, the clean tongue flashing behind clean teeth, and she would laugh. Then she slipped her littlest finger into the eye of the black girl’s asshole. Usually in porn he liked that. Usually this was the moment he would go faster and faster. Something wasn’t nice though, or something was too nice. Something wasn’t working for him. It was to do with the way she moved her clean fingers with the glued-on nails; a child playing an instrument. Competent. The nails were pink like her hair.

‘Wahayhay!’ Aengus had said. ‘Oh baby, yeah!’

She was looking at Oisín. He tried to say it too, ‘Way – yeah, come on baby!’but when he opened his mouth the sound didn’t come – only a breath without voice. He felt nauseated. Too much dope, maybe? Too much drink? His mind was moving in all the wrong directions and he couldn’t focus.

‘Oisín’s smitten – oooh! Hey Pinkie! Oisín lurves you – Ha ha!’

‘He wants you to give him one backstage – don’t you Oisín? Whatd’ya say Pinkie?’

Kevin reached out to touch her bum. Her eyes flashed. The wiry, jaundiced bodyguard stretched out an arm, restraining him gently and easily. Kevin backed away, palms up in surrender.

‘Ah no – I’m only messin’ baby! It’s just you’re a lovely looking girl you know that? Nah, you’re sound-out baby, I’m only messin’ with ya. You’re sound-out, so you are.’

If they had known what Oisín was really thinking they would have called him a pussy, a college boy pussy! Pinkie didn’t really want to saycock.She wanted him to think she did though, and that made it worse. That made him hate her.

Aengus and Kevin were both staring at him now. Any moment they would realize what was wrong. They would know he was a pussy college boy, too good for them, not one of the lads any more at all.

He thought ‘Pussy,’ but not in a sexy way. ‘Bitch,’ he thought. Then he thought the word ‘Man’ – ‘Man. Man. Man.’ He took a swig of beer and swished it about, wetting his cheeks and palate. He sucked a breath and the air felt cold against his teeth.

‘Wooooaaah – come on Pinkie! Give it to her! Oh that’s right, yeah, that’s right like that. Oh yeah!’

Relief. He really meant it – she was hot, hot,HOT! He was one of the lads again. No one had even noticed him transgress. He shouted louder.

‘Woooaaah baby! Good girl …’

The lads didn’t speak after the performers finished. They had a drink – paying for it this time – and went back to the hostel. The barman at the hostel stayed on late into the night. When the lads were the only remaining customers, he served them something like hash, only it was black and squidgy and could be kneaded between fingers and rolled into a worm shape that lay neatly beside the tobacco. That night, his head on the damp hostel pillow, forcing his mind to wade through speech, Oisín asked Denny if he had liked the show.

‘It was hot,’ he said, but confessed that he preferred the private sex shows he had been to last time he was in ’Dam. They were less embarrassing. You sat in a booth in the dark, he told Oisín, not even the performers could see you, and there were clean tissues provided to wipe up your cum. He took Oisín to one the next day. He was right, they were less embarrassing.

Sitting up in bed, Oisín kept his hand pulsing on the mouse. A blonde with pigtails, a huge red lollipop entering her open mouth, gazed out from the screen. Her school shirt was torn open to reveal weighty breasts: large nipples as red as the sweet. Another girl licked the lollipop too. She was facing away from the camera. Her white knickers said ‘Princess’ on the bum. They weren’t really schoolgirls so it was okay. They weren’t really that young. Not with tits like that! Oisín reached into his jocks with one hand and kept clicking with the other.

That night after the ‘Ying and Yang’ show, he hadn’t been able to sleep. Denny had snored heavily in the bunk below him. Every time Oisín closed his eyes he’d seen that bodyguard, the gentle, firm way he had eased Kevin back. The long neck had held up a shrunken face, a glassy-eyed expression that never changed. He looked like a meerkat, Oisín thought. His arm wasn’t very thick but it was strong, and Oisín could see the ligaments and veins all twirled together and moving slightly under the yellow skin.

Sometimes at these moments – Oisín’s hand moving vigorously, the delicious warmth twinging higher and higher, pounding towards release – that bodyguard would stalk into his room and run a chilly finger down his spine. That blunted his arousal. It was the girl-on-girl action that had reminded him. He clicked his way to the deep throat pictures. ‘Gagging Bitches’, said the link. Then there was a description of the site:

You know what we say to foreplay? We say FuckOFF! We take hot young cunts and fuck their little faces until they’re gagging and their mascara runs. Then we fuck up all their other holes. She may weep all she likes. Stopping ain’t our style …

There were twelve options: girls’ names with thirty-second teasers. There was a picture of a blonde woman in a pencil skirt and a white blouse. She was wearing librarian glasses and chewing a biro: ‘Joan from downstairs,’ it said. ‘Let’s begin by smashing those specs. Watch us turn the secretary from hot whore to cumbucket. See love tunnel turn to train wreck while three men fuck her till she weeps …’ Under the name ‘Helen’ it said ‘This dumb whore thought vomiting would get her off the hook … but there’s more than one way to fuck a kitty.’ The picture was of a girl in red lacy underwear with a vice fixed to her jaw. She was cute as a doll. She had small, round breasts hugged proudly by the lacy red cups, cartoon-yellow hair in a high ponytail, and slutty silver eyeshadow. There was a penis in her mouth, and a man’s hands holding the handles of the contraption. There was semen on her stiff, black eyelashes.

While he waited for the teaser to load, Oisín tried to think of the real Helen, the girl from last night, but she kept eluding him. The video failed to load so he scrolled down for another. The deep throat album had been updated since last time. There were more Asian girls now. Their slender necks bulged like a snake that has swallowed its prey. Oisín liked the Asian girls – they were so neat. Their red-lined lips and pink cat’s tongues looked sophisticated against the slop of shaved testicles.

Aengus sent the best free porn links. His taste was the same as Oisín’s: really sexy girls, definitely no airbrushing. Like Oisín, he wasn’t into gross stuff. He preferred the girls with natural tits touching themselves and licking their nipples, drinking shot glasses of semen or popping beads up their bums and things like that, not the really mad shit.

As for shit – not into that at all. None of the lads were – except maybe Kevin.

Kevin had once sent him a mobile phone video of a fifteen-year-old being fucked in an alley by three different guys. It was rape. It was on the news and the boys had to go to juvenile prison. You couldn’t really see much. One of the guys had recorded it and sent it to someone whose brother sent it to Kevin. That’s how they got caught, by sending the video around. The girl hadn’t told on them. Oisín didn’t know the girl, but he recognized the uniform. She was heavy with white breasts. He had deleted the message.

Cleaning up with a piece of toilet roll, Oisín remembered about changing the sheets and decided he’d do it later. He noticed that his cum was clear this morning. It was strung together like snot. After taking a shower he made some coffee in his kitchenette, stirring the granules languidly until they were completely dissolved.

Cassandra isin the shower when you leave. She hears you and roars, ‘Bye Helen!’

With that simple phrase, ‘Bye Helen’, Cassandra makes you feel accused, as though you have betrayed her by leaving, as though you were sneaking off. This is a talent that Cassandra possesses.

You walk into the library and then out again the other side. You head up Grafton Street and down again and all the way to the quays. It’s one of those dull, dank days when the cold is in your bones and your face feels too exposed. The river has risen with the rain. It has swallowed the strings of decomposing apple butts and faded crisp packets that are usually visible over the water line, dried to the cement walls of the Liffey.

You buy cat litter at the pet shop on the quays, then walk to Dunnes Stores for granary bread, hummus, and washing-up liquid for the kitchen. Then, feeling bored and careless, a tub of chocolate cornflake squares and some ready-made raspberry jelly from Marks & Spencer’s that you consume in your room, stroking the kitten and reading the same page ofAs You Like Itfour times, each time forgetting to pay attention.

I’ll gofor a walk before that lecture. While Helen’s getting dressed I take a thorough shower, exfoliating with an expensive body scrub prescribed by the make-up artist on my last modelling gig. The packet says it contains ‘peach-stone extract’, and ‘organic walnut’. There are words like ‘sensual’ and ‘indulgent’ written across the lid, but it’s unpleasant stuff really: pink, peach-smelling goo with orange grains in it. These grains represent either the peach-stone extract or the organic walnut bits. It says to use a loofah, but I only have a sponge. There are instructions on which lathering methods to use for maximum exfoliating effect. The whole project is extremely tedious and I don’t think I’ll have the willpower to repeat it daily, whatever the make-up artist says.

I can hear Helen’s door click shut. She passes the showers without saying goodbye and starts down the stairs. I call, ‘Bye Helen!’ It makes me feel stupid and needy, shouting after her like that.

After making the effort to exfoliate I decide to go the whole hog and put on make-up as well; evening out my skin tone and brushing on some too-black mascara. This makes my eyes look larger and darker than they already are, which is complemented by the black of my bobbed hair. The effect I am going for is big smudges of eyes framed by a glossy black ball at the top of my neck. The bob is a bit ‘two seasons ago’ – Helen told me that – but if I blow-dry my hair this look works well for me. Otherwise it sticks up and out as though someone has knifed it off in clumps and I look like a crazy person. When I look like this, men don’t evaluate my bum and the ladies in Brown Thomas do not offer me perfume samples. On those days I wear tracksuit bottoms. I sit in the park and no one sees me.

I change my mind about wearing jeans, and put on boots and a skirt instead.

Nothing has happened today but it’s already the afternoon. The days just slip off in college; it’s the sparse timetables, the hanging about. Helen’s lazy, happy mood has rubbed off on me. I like the softness of the afternoon air and the pain of the cobblestones through my shoes. I even like the sound of someone playing with a guitar in his room; a vain boy’s hope to be heard. What a sin to have ever been sad. I will give everything in my purse to the homeless man at the Nassau Street entrance and, having done all I can, let him drift softly out of mind. This is the best way to live. This is the only way to be happy, and sane, and good.

He is not there today. Next time, then.

Grafton Street is full of strangers. You can lose yourself in all their bustle, all their purposes, all their loves and the little pet hates, all their self-importance.

A stout refugee woman tugs at my sleeve. She is my age with proud features around her snarl. Her baby is swaddled in a filthy tiger-print shawl. It has an ancient, knowing face and its nostrils are sealed with snot. She pushes it at me so that its face is inches from mine, and we blink dumbly at one another. Its mother pulls it away again, irritated.

‘Please lady.’

I am not a lady. She pouts and asks again, and there’s something not right about it. Her hands are cupped with embarrassing servility. I give her a euro and feel worse than if I had ignored her. I’m saving my money for the homeless man. He might be there when I get back.

I try to recover that happiness, the feeling I had when I first set out for this walk. I should be able to do that, to carry a mood with me. I should not be so easily shaken. I try to love the crowds, the smiles of strangers and the buskers’ music, the crumbling, bitter old man muttering to himself as he skulks along the wall. He growls, jabbing his elbow into me spitefully as he passes, running his other hand against my hip, his flaking grey heart desperate for the bulk and warmth of another life. The impact shocks. It makes me ashamed of my youth and my strength. I do not want to carry the weight of his loneliness. He smells of unwashed clothes, of packed dead skin.

What should I do to appease him? Too late, he’s gone. He’s crazy. There is nothing I can do for him. When there is nothing you can do, walk away and don’t look back. Leave it in a bundle on someone’s doorstep.

I sit by a window in Bewley’s and stare down at the busy street, eating a chocolate doughnut made of something I can’t identify. It is not chocolate on the top, that’s for sure. It’s chocolate flavour. I need to calm myself, slow my pulse, take stock.

Must head back for the lecture.

The homeless man still isn’t there.

I wish I wasn’t so early. The hall is occupied and everyone is waiting around in chatting clusters. I strike up a conversation with a few girls from my tutorial group.

‘Do you know who’s giving the lecture?’

‘No, I hope it’s Dave again, fantastic isn’t he?’

‘He’s funny, yeah.’

Dave.I don’t know which one that is.

‘I had him for tutorials last term and oh my God, he issoomuch fun …’

Cassandra isgone when you get back. She must have a lecture.

Sitting on your bed, your legs crossed, resting your fingers on a small cushion someone gave you with ‘Helen’ embroidered on it, you paint your nails with the ‘Cherry Bomb’ polish you bought yesterday. It’s that new one-coat-only rapid-dry stuff that only takes a minute, but you blow on it anyway out of habit. You hold your hands out before you the way you do, fingers splayed, wrists bent back like the spine of a ballerina, head cocked like a parody of girlishness, lips puckered in concentration, while the first coat hardens. Then you apply a second layer, then a third, shrugging away your curls when they fall over your eyes.

There area few seats in the back row of the lecture hall that aren’t lit by the orangey light. Sitting here I feel hidden. It’s a professor I haven’t seen before. Old. Twenty minutes into the lecture and already we know that he is separated after thirty years of marriage, that we are lucky in our innocent belief in love, that we cannot understand this poetry as we have not yet experienced the disillusionment of failed love.

A strange word: love. A fool’s word everyone wants to trust, even this poor, broken-hearted, obsessive old sod, dismantling his like a public autopsy. He spits his words like bile as we watch and listen and scribble notes. A caged gorilla flinging his shit at spectators. He hasn’t shaved.

‘Any questions?’

‘Well, why is the poet so respected? What is the point in literature, if only those who have experienced the events described can empathize? Is empathy all it is? What do we learn?’

I bore myself when I start like this. It is my argument against everything: ‘Isn’t it just self indulgence for the middle classes/for the upper classes/for the colonized/for the women? What isachieved?’

I shouldn’t have started. He cares about this dead writer. He cares about this poem. God, let him have it if it matters to him. Let him be right. His wife left him, he stinks. I can smell it all the way back here. It’s that rotten-love-carcass smell that makes humanity revolting. He has mustard-like gunk clotting his eyelashes, and no one will love him ever again. I bet he hates our rosy cheeks and our reverence. I bet sometimes he wakes up and wants the dark back.

The girl next to me, Alice, twists a rope of hair around her fingers, nodding.

‘Good point actually.’

He glares at me. ‘It used to be harder to get into this course. Before the points system. We knew the kind of minds we were to deal with. Not any more. It was about culture then. Culture. Not Leaving Certs. Notpoints.’

Helen told me it’s actually worse than that – not only did his wife leave him, she left him for another man, a younger and more successful academic. ‘And,’ she told me, ‘this academic lectures at Cambridge. The wife and kids go and live with him. Then the guy – the guy who stole his wife and lectures at Cambridge, whose book on Chaucer was published this year – has an affair with the sixteen-year-old daughter and gets her pregnant.’

He shuffles his papers. His fingers are trembling. He’s a drinker, this lecturer. If you go up close you can smell it off him. What sort of knowledge will we inherit from this elder?

He begins to explain again,

‘You cannot understand. How can you possibly understand what Chaucer means, he who lost his children, who lost … who lost … everything … in a fire …’

Poor lonely old sod passing us this world like a poisoned gift: a feast of our grandmothers and our own little children, shoulder blades and eyelids and all. Our test-tube embryos served up like caviar.

I resolved to go to the library after the lecture, so I resist the temptation to go home and see if Helen’s back. I wish I had removed that dead fish though. I hate to think of her noticing it alone, lifting it out with her fingers, handling the weight and the cold of that little corpse. I keep seeing his round sunken eye and the stiff curve of his body lying just below the surface of the water.

My student card does not swipe me in like it’s supposed to. Instead I have to show it to the smug man at the desk, who pretends to scrutinize it. Then he faces the other way and holds two outstretched fingers towards me, the card slotted between forefinger and index. His arm is too high, and I have to reach up on my toes to snatch it back. Pushing a button under his desk, he releases the swing bar so that I can pass through. I want to say ‘thanks’, but only my lips move. A pain catches where the sound should be. That happens to me sometimes.

The library is simmering with synthetic light and that hostile purr computers give off. There are a lot of computers in the library. They are dotted about in pairs, stuck back-to-back and perched on metal stands that make me think of spaceships. Everybody moves about in silence, tapping at computers, turning pages, scribbling in feathery sounds with soft felt-tips, or biros that dent the paper. I walk through desks of students, computers, bookshelves, forgetting what I’m looking for. I feel loud. My shoes are making a clack-clack sound and I don’t know what to do with my hands. I have no pockets, so I just hang them both on the shoulder strap of my bag, but that doesn’t feel natural. I don’t know why I wear heels. I am too tall as it is.

Occasionally someone at a desk lifts their head as I pass, clocks me, and returns to their work. I try to wear an expression of urgency – I need to think of a dissertation topic, and then I need to find books on it. This is not the right section of the library though. The dissertation has to be on Victorian literature, and this is the theatre section.

I hate this quiet crowding. The huge building is packed: every wide, low-ceilinged room is lined with books and periodicals and computers, and then filled with people. All these people filling the space have words, sentences, stories running in their heads. There are so many different lives racing on in here and no one speaks. Their silence is a smouldering of voices – like fire under a blanket.

My chest contracts and my eyes pulse. The people walking around the library look hazy; anything I try to focus on blurs and sways. If I am not careful I will forget how to breathe and my eyes will fog over. This is another thing that happens to me sometimes.

I make for the bathroom where it reeks of antiseptic and the kind of sewage smell you can’t clean away. I dart into a vacated cubicle, bolt the door, and sit on the closed seat, shut in with that nostril-burning contradiction of bacteria and chemicals. Head between my knees, knuckles pressed into my eye sockets, I concentrate on breathing until the blood stops fizzing in my veins.

I focus on the interior of the cubicle. In front of me the door frame: white, with a black sliding lock. To my right the blue sanitary disposal unit, pregnant with knowledge of its festering contents. The scrawls on the toilet-roll holder clamour for advice:

Swallow or Spit?

I can’t poo!

I’m in love with a married man, I know he loves me but he doesn’t want to hurt his wife or kids – should I stay with him? Don’t know what to do.

Three girls, in contrasting shades, have given her advice.

The next question is written in luminous pink felt-tip. The writing is curly, the ‘i’s dotted with halos.

23 and a virgin – weird?

The first reply tells her she is ugly. The second that her first advisor is a slut and that the virgin is right:

Not at all! I waited for the right person and so happy I did!

Someone else has responded to this advice:

Well so did I but it turns out he’s shagged half of college and gave me two differentSTDs! Sex doesn’t mean shit to men don’t fool yourself love! Lose it to a vibrator!

There is a maxim beside it in different handwriting:

Virginity is like a balloon! One prick and it’s gone!

I use my eyeliner to write on the door:

It is time to forget. The House of Atreus is better left vacant. Let the wind howl through its openings. Let worms devour the bloody carpet. It is time to forget.

I look at the words scrawled there in black charcoal and I can see they look like ravings. I use toilet paper to smear them out. At the sink I watch the water run over my hands. They’re the kind of taps that you don’t have to switch off, which I prefer because there seems little point in cleaning your hands if you’re just going to touch the dirty tap again. They always run out too soon. I press the tap three times, using the upper side of my wrists instead of my fingers. I like when my hands become so cold it feels like they’re dead.

There’s a harsh, ultraviolet light in here designed to prevent you from shooting heroin on the loo. It stops you from seeing your veins. It also makes your face look like somebody else’s; like you in a different world, under water, or on the moon. You in negative. It shows every pore of your skin. My reflection stares over the sink like a stranger. The nose is too big. Severe cheekbones jut in a way that gets me modelling jobs. They are unattractive. They make my face look like a man’s.

I smile at the reflection, smooth some lipstick thickly onto my mouth, and step back into the library.

Between the toilets and the steps up to the Ussher Library there’s an undefined area with computers and benches, no desks or books. It’s supposed to be part of the library but when there are no supervisors around students talk and make phone calls here. A girl with a small, lopsided jaw is sitting on the bench talking on her mobile. From looking at her I can guess she is a Business Studies student or something like that: streaky fake tan, pastel knits, tight jeans. She scribbles on her foolscap as she speaks.

‘No Mom. No, I’m not going out tonight, Itoldyou. ’Kay. Ya. ’Kay. Will someone collect me from the Luas? I don’t have the car. ’Kay … Oh Mom? We didn’t have to go to lectures today cause – am – a girl died. Ya I know. I know – hardly bodes well for me does it? Like if some people are actually killing themselves already like – and exams haven’t even started!SUCHa high-pressure course. I know, what a week! Yeah. Oh, she jumped out a window. I dunno, I dunno. Maybe. Ya – I know. It’s so sad isn’t it? Not really, like I knew her to see … I think she had problems. Ya, ya … ya, ’kay. I’ll call you when I’m on the Luas. Bye! Bye. Bye-bye-bye …’

I remember what I came in for. I’m looking for a book of critical analyses ofAlice’s Adventures in Wonderland, hoping it will give me a dissertation idea. I look up the index number on the computer, write it on my hand and try to locate it on the shelves, mouthing the alphabet as I run my finger along the combinations of letters and numbers sellotaped to the book spines. I have located the space whereARTS8287TH L5 should be, but in its place is a pale blue cloth-bound book calledThe Victorians and The Cult of The Little Girl. It’s bound to have something onAlice in Wonderland. Bunny holes and all that … In any case it will have to do. I take it to an empty desk and sit down.

The cover feels pleasant: sack-cloth texture greased by decades of touch. I run my palm over it and then over it again before I open it. The pages are the colour of tea stains. A tiny insect, the kind that is not hatched from an egg, but born from darkness or rotting fruit, uncurls itself in the crease of the spine, and moves slowly, sleepily over the word ‘truths’. The tiny life has all the magnetism of something secret, primordial, significant in a way that I will never understand. Then it unfolds its wings and pings off the page. That shocks me. I didn’t imagine it having wings.

The girl beside me is left-handed. Her elbow prods mine and we both make a lethargic gesture of apology.

There’s no fresh air in here, it’s all been used already: inhaled and exhaled through noses and mouths; then sucked in and spewed back out by the humming air conditioner. That means the oxygen must be quite low by now, so everyone is drowsy. I am breathing someone’s cough, someone’s sigh, someone’s silent fart, blended and filtered by the machine. In London the water is sterilized sewage. There isn’t the silence here to think. Strangled words whoosh about –Afro-American Literature and Female Identity … Swallow or Spit? … Saussure and Truth … I’m in love … Salmon Rushdie and the West … Yeats and Apocalypse …SUCHa high-pressure course … What should I do? … The Big House in Anglo-Irish Literature … What should I do? What should I do? What should I do?

After the‘Renaissance Drama’ lecture, Oisín had a few pints in the Buttery with some of his class. A slim redhead with a push-up bra laughed at his comments on the chirpy, round little lecturer, though he knew himself that his observations were not particularly funny. When she giggled her gums showed. Oisín was encouraged: ‘I thought he was going to topple over, the way he kept swaying on his heels!’

Her lips shrank back like melting wax, exposing gums and teeth, and a high trill rolled out. It kept going long after it should have. Maybe he was in there. ‘I rooted a ginger’; that’d be the subject title when he mailed the lads about it.

Sharon from film studies was there too, at the other side of the bar. She didn’t see him. He had what might be a date with her tonight. He was suddenly a little panicked and didn’t want her to see him. He would be embarrassed. She might notice his dandruff and change her mind about coming over tonight. There was a short Indian boy talking at her energetically, but Sharon gazed about the dark bar.

The skin beneath Sharon’s eyes sank in brown folds like an old man’s. Her hair was cropped along the jaw line, with a straight fringe that hung over her eyebrows. It was a frank, plain face, but not repulsive.

Oisín liked Sharon, he didn’t know her very well but he knew he could sleep with her and that made him defensive about her ugliness. He didn’t want her to be seen that way. He wanted to grant her beauty. It was something about the gape of those unbeautiful eyes, like a vacuum that sucked you warmly in.

Sharon was long-bodied with no waist and strong, wide-set shoulders. She wore dollar scarves. The Indian boy didn’t notice that she wasn’t listening. He looked like he was talking about maths or something. He wasn’t looking at her any more. Instead his gaze was fixed on his own hands as he explained something with them, drawing lines and circles and then chopping them to pieces with a downward swoop of the hand. She put her hand on his arm, told him something gravely. The boy raised his eyebrows as though surprised or impressed. They waved at each other as she rushed out of the Buttery. She hadn’t seen Oisín.

Indian men treated girls like Sharon as though they were boys. That was something Oisín had noticed. There was one in his ‘Tragic Patterns in Greek Theatre’