Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Arc Publications

- Kategorie: Poesie und Drama

- Sprache: Englisch

Jan Baeke, the award-winning Dutch poet, has, in Greater than the Facts (Groter dan de feiten, 2007), created an intriguing filmic world in which tensions are rife and nothing is quite as it seems. It is a world whose elements keep recurring, coalescing little by little into dreamlike leitmotifs – a bus journey, a hotel room, dogs, cigarettes, fire, a blind man, a canary, a man and a woman in love. And love, however fragile it may be, is a major theme of this collection, for "where there's fire, there's warmth for two". Antoinette Fawcett's poetically sensitive translation gives a clear sense of Baeke's style and poetic drive, and enables the English-speaking reader to explore in full this key collection in Baeke's œuvre.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 107

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2020

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

BIGGER THAN THE FACTS

Published by Arc Publications,

Nanholme Mill, Shaw Wood Road

Todmorden OL14 6DA, UK

www.arcpublications.co.uk

Copyright: © Jan Baeke, 2007 Originally published by Uitgeverij De Bezige Bij, Amsterdam

Translation copyright © Antoinette Fawcett, 2020

Translator’s Preface copyright © Antoinette Fawcett, 2020

Introduction copyright © Francis R. Jones, 2020

Copyright in the present edition © Arc Publications, 2020

978 1911469 57 5 (pbk)

978 1911469 58 2 (hbk)

978 9911469 59 9 (ebk)

Design by Tony Ward

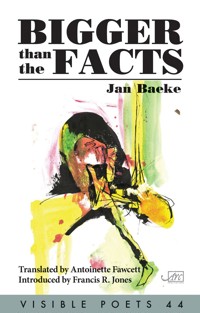

Cover picture from an original painting by Marcus Ward, by permission of the artist

Printed by PrintondemandWorldwide.co.uk in Peterborough, UK

This book is in copyright. Subject to statutory exception and to provision of relevant collective licensing agreements, no reproduction of any part of this book may take place without the written permission of Arc Publications.

This book was published with the support of the Dutch Foundation for Literature

‘Visible Poets' Translation Series

Series Editor: Jean Boase-Beier

for Marrigje / voor Marrigje

CONTENTS

Translator's Preface /

Introduction – Writing a Different Story: Bigger Than The Facts and Its Translation /

Only the Beginning Counts (nos. 1-10) /

Alleen het begin telt

Summer's Way (nos. 1-13) /

De kant van de zomer

What Couldn't Be Otherwise (nos. 1-13) /

Wat niet anders kon

The Dogs (nos. 1-13) /

De honden

I Invented Him (nos. 1-13) /

Ik heb hem bedacht

Acknowledgements /

Biographical Notes /

TRANSLATOR’S PREFACE

Since I first learned how to read, reading has been a form of adventure for me, taking me into the unknown and making unexpected things happen. Every new written word I recognized in my early childhood lit the world in a little explosion of emotion that means I still remember when I first saw and sensed that word. The reading of the text fixed the word in my memory much as a photographic fixer stabilizes an image, while all the emotions and actions that went with that first exposure to a specific written word remain part of that word’s aura forever.

This earliest form of reading was arguably rooted more in laborious decipherment and delighted recognition than in reading as I now experience it, but I believe that all true and attentive reading is indeed a form of adventure: a venture into a different way of seeing the world; a making the familiar unfamiliar again; an introduction to something totally new and unexpected; or a facing-up to one’s own deepest fears, prejudices and anxieties.

What I felt in my earliest excursions into written English I also experienced in Dutch. I was a child of four in a Dutch kindergarten where the poems and songs I learned introduced me to talking chickens, skating bears and singing hedgehogs. The short time I spent there was my only form of Dutch education, but that experience of learning to read in my second language stayed with me ever afterwards. If anything, the experience of reading my first words in Dutch was even more of an adventure than my early excursions into the English written word; certainly this writing gave more promise of the strangeness, mystery and musicality of the world and marked my first independent ventures into poetry, song and story.

But that world of wonders was soon closed to me, when English became the only language of my schooling and my mother no longer spoke to her children in pure Dutch, but in my father’s tongue or in a mixture of Dutch and English. A series of English boarding schools, a strict Catholic education, the English horror of bilingualism, all led to a lack of development in what had at first been a language that was as natural to me as English. The Netherlands became for me the land from which I had been exiled and, in spite of occasional family visits, its language, customs and culture existed behind the locked gates of memory and longing.

Once I was an adult I did everything I could to re-enter the lost country and re-find the hidden language. I made my own study of the language and literature; I visited the country often, and even lived and worked there for several years; I chatted and conversed in Dutch, and most importantly, perhaps, looked for books in Dutch and Flemish bookshops that would engage me and give me the energy and motivation to continue my quest to find words and poems and stories that would continue to create those little explosions in my mind.

In December 2015, I was in the Netherlands for a few days to attend a translation workshop and to make a ritual visit to a good bookshop. As I searched the poetry shelves for something to re-ignite my passion for the language, and to chime with my sense of its mystery and adventure, I chanced upon a little book, the size and shape of an A5 diary. It had a bold, stylized cover from which a larger-than-life canary stared sidelong at me, with a quiet air of challenge or warning. This book was the book I would spend almost the next four years reading, thinking about, worrying at, discussing, translating, and re-translating. It was Jan Baeke’s Groter dan de feiten, the book you now hold in your hands or see on a screen as Bigger than the Facts, its English offspring and conversation partner, or perhaps better said, its companion.

The canary on the cover was the lure into this particular adventure, but the words that flew out of the book and into my mind were what induced me to embark on the translation project. They were both clear and peculiar. I could understand them in their often naked simplicity (stars and coldness, dogs and canaries, cigarettes and smoke and fire), but their relationship to each other was not always obvious. The poems were full of surprises and puzzling statements, which were not annoying or irritating, as unmotivated surrealism may sometimes seem. They formed a kind of hyper-reality which managed to say something important about being human “in times of fire and fighting back” (‘Summer’s Way: 2’). They suggested to me that it would be worth embarking on a translation journey that would investigate, interrogate and travel with the whole text, the complete work of art that its poet, Jan Baeke, had created.

It became an essential mantra to me at an early stage in this project that if I were to be able to give the text the reading it deserved, it would have to be translated in its entirety. The translation journey would have to explore every element, every feature and incident of the world evoked by the poet and not merely come to a standstill inside an individual poem. That meant that I had to accept the frustration of disorientation, of not knowing and not understanding, just as much as the joy and delight of those readings and subsequent translations that made sense to me from the start.

As the translations began to take shape I recognized more and more the unity of Groter dan de feiten and felt not only that it had to be explored in its entirety through the act of translation, but that if it were to be published in English it also had to be published as a single work. All the individual poems cast light on each other. The images, situations and characters recur and gain weight and complexity as the work unfolds. It seemed to me, therefore, that it would be an injustice to the shape of the piece as a whole, to its manifold scenes and images, to make selections from it and then to balance those selections with poems from Jan Baeke’s other books. That would be like making a translated selection from Eliot’s The Waste Land, ‘Death by Water’, for example, and butting that up against ‘The Naming of Cats’, ‘The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock’ and other favourite Eliot poems, with the intention of covering as much of the oeuvre as possible. There is a place for that kind of representative selection, but in this case I felt that the book deserved a translation that would allow the English-speaking reader to make a journey of discovery within it that would parallel the journeys taken by its often admiring but sometimes baffled first Dutch readers.

Groter dan de feiten (2007) was Baeke’s fourth book of poems and perhaps the first in which he discovered a way to make a unified work of art through a complete book-length sequence of poems. It was and remains an important key to his work as a whole and as such has not lost its relevance in the intervening years. It tells a story and has characters – at least two – who enact that story in voices that are not the poet’s own, but behind which the poet’s mind is working. It is not clear who the characters exactly are, what the setting for the story is (perhaps vaguely southern European or Mediterranean), and in what period of time it is set. That there is a male voice and a female voice gradually becomes apparent, as does the historical range and cultural allusiveness of the five-part sequence. As a reader, my skin prickled and the back of my head tingled when I thought I recognized some of those allusions: to myths and stories, to beliefs and sacred books or practices, to films and art and philosophy, to actual facts, sometimes hard to face, and to the ambiguous nature of what it means to be human: to suffer and to deal out suffering; to love, to give love, and to accept it.

As a translator I did not want to pin the English-speaking reader down to a single interpretation. I wanted the reader of these translations to look with an open mind at the poems, to look coolly at the images as they play out in this sequence, to look obliquely at an often dark reality through details that are “bigger than the facts” (‘What Couldn't be Otherwise: 12’). “Looking,” as the epigraph poem tells us, “is the most miraculous child of darkness”. Or: “I thought that looking was the most important” (‘Summer's Way: 6’); or again, in the same poem: “You have to look during the pounding and the praising”. If you look properly, even, or perhaps especially, through the lens of a post-modernist, fragmentary, everyday epic, you may recognize that you are implicated in our histories of suffering, just as you also have the potential to be uplifted, given meaning, by little acts of love and significance, “emergency thoughts” that “go to the heart” and then “jump” (‘The Dogs: 13’).

To retain those ambiguities, which are expressed in a clear and pure language, in poems that ask questions but do not directly answer them, was extremely difficult. It was important for me not to close off multiple interpretations, yet the act of choosing to translate a particular word in a particular fashion does inevitably shut out certain possible meanings or implications. Should the Dutch word “wonderlijk” in the epigraph poem be interpreted as “miraculous”, “marvellous”, “wonderful”, or as “strange”, “peculiar”, or “weird”, for example? These are all possible translations and whatever choice is made in English, the English-speaking reader will be pushed in a particular direction. Perhaps I decided to choose “miraculous” because of my own adventures in the Dutch language, my own ventures and adventures in life; but I also felt that the word vibrated best with the layers of allusion in the sequence as a whole.

When we translate literature we translate as people, as human beings, with bodies and feelings, with our own histories and idiosyncrasies, and this is especially true when we translate poetry, which through its sounds and rhythms works on our emotions and our bodies. The sounds and rhythms of Dutch and English are not the same as each other, but because the two languages are quite closely related it is possible, even with free verse, to try and achieve some approximation of the original form: the balance of long lines against shorter lines; the placing of certain words at the end or at the start of a line; the surprise or reversal of expectation that a particular enjambement may create. At the same time, however, as wanting to do justice to the manner in which the Dutch poems are expressed – their tone, their sound, their feeling – it seemed essential to me to do so in a way that would resonate in English. The words of the translations were tested and re-tested on the tongue until voices emerged that spoke to me in English as I had heard the Dutch voices speaking to me in Dutch. It is not only “looking” that is “important”, but hearing too, especially where poetry is concerned.