2,73 €

Mehr erfahren.

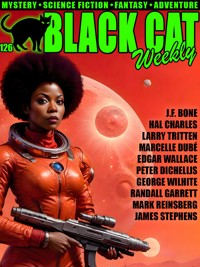

- Herausgeber: Black Cat Weekly

- Kategorie: Fantasy und Science-Fiction

- Sprache: Englisch

This time, we have an original mysteries by George Wilhite (courtesy of Acquiring Editor Michael Bracken) and Peter DiChellis (a locked-room mystery), as well as an original science fiction story by Larry Tritten and me. (It is a posthumous collaboration—Larry passed away in 2011. I acquired his copyrights some years ago and have been working on reprinting his stories, as longtime readers of BCW will realize. One particular story, with a terrible name, just didn’t work. So I rewrote it, retitled it, and am pleased to show it off here. I hope you all enjoy it.) And Acquiring Editor Barb Goffman found a great tale by Marcelle Dubé.

We also have classic novels from British mystery author Edgar Wallace and Irish fantasist James Stephens, plus classic science fiction from Randall Garrett, J.F. Bone, and Mark Reinsberg. Good stuff.

Here’s the complete lineup—

Mysteries / Suspense / Adventure:

“Hanged By the Neck Until…,” by George Wilhite [Michael Bracken Presents short story]

“The Puzzle Palace Perplex,” by Hal Charles [Solve-It-Yourself Mystery]

“Tethered,” by Marcelle Dubé [Barb Goffman Presents short story]

“Behind a Locked Door,”by Peter DiChellis [short story]

The Just Men of Cordova, by Edgar Wallace [novel]

Science Fiction & Fantasy:

“Free-For-All-Way,” by John Betancourt and Larry Tritten [short story]

“Respectfully Mine,” by Randall Garrett [short story]

“The Missionary,” by J. F. Bone [short story]

“The Satellite-Keeper’s Daughter,” by Mark Reinsberg [short story]

The Demi-Gods, by James Stephens [novel]

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 659

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Ähnliche

Table of Contents

COPYRIGHT INFORMATION

THE CAT’S MEOW

TEAM BLACK CAT

HANGED BY THE NECK UNTIL…, by George Wilhite

THE PUZZLE PALACE PERPLEX, by Hal Charles

TETHERED, by Marcelle Dubé

BEHIND A LOCKED DOOR, by Peter DiChellis

THE JUST MEN OF CORDOVA, by Edgar Wallace

CHAPTER 1

CHAPTER 2

CHAPTER 3

CHAPTER 4

CHAPTER 5

CHAPTER 6

CHAPTER 7

CHAPTER 8

CHAPTER 9

CHAPTER 10

CHAPTER 11

CHAPTER 12

CHAPTER 13

CHAPTER 14

CHAPTER 15

CHAPTER 16

CHAPTER 17

FREE-FOR-ALL-WAY, by Larry Tritten and John Betancourt

RESPECTFULLY MINE, by Randall Garrett

THE MISSIONARY, by J.F. BONE

THE SATELLITE-KEEPER’S DAUGHTER, by Mark Reinsberg

THE DEMI-GODS, by James Stephens

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Book I

I

II

III

IV

V

VI

VII

VIII

IX

X

XI

XII

Book II

XIII

XIV

XV

XVI

XVII

XVIII

XIX

Book III

XX

XXI

XXII

XXIII

XXIV

XXV

XXVI

XXVII

Book IV

XXVIII

XXIX

XXX

XXXI

XXXII

XXXIII

XXXIV

XXXV

COPYRIGHT INFORMATION

Copyright © 2023 by Wildside Press LLC.

Published by Wildside Press, LLC.

wildsidepress.com | bcmystery.com

*

“Hanged By the Neck Until…” is copyright © 2024 by George Wilhite and appears here for the first time.

“The Puzzle Palace Perplex” is copyright © 2022 by Hal Blythe and Charlie Sweet. Reprinted by permission of the authors.

“Tethered” is copyright © 2022 by Marcelle Dubé. Originally published in Crime Wave 2: Women of a Certain Age. Reprinted by permission of the author.

“Behind a Locked Door” is copyright © 2024 by Peter DiChellis and appears here for the first time.

The Just Men of Cordova, by Edgar Wallace, was originally published in 1917.

“Free-For-All-Way” is copyright © 2024 by John Betancourt and appears here for the first time.

“Respectfully Mine,” by Randall Garrett, was originally published in Infinity, August 1958.

“The Missionary,” by J. F. Bone, was originally published in Amazing Stories, October 1960.

“The Satellite-Keeper’s Daughter,” by Mark Reinsberg, was originally published in Fantastic Universe, December 1956.

The Demi-Gods, by James Stephens, was originally published in 1914.

THE CAT’S MEOW

Welcome to Black Cat Weekly.

This time, we have original mysteries by George Wilhite (courtesy of Acquiring Editor Michael Bracken) and Peter DiChellis (a locked-room mystery), as well as an original science fiction story by Larry Tritten and me. (It is a posthumous collaboration—Larry passed away in 2011. I acquired his copyrights some years ago and have been working on reprinting his stories, as longtime readers of BCW will realize. One particular story, with a terrible name, just didn’t work. So I rewrote it, retitled it, and am pleased to show it off here. I hope you all enjoy it.) And Acquiring Editor Barb Goffman found a great tale by Marcelle Dubé.

We also have classic novels from British mystery author Edgar Wallace and Irish fantasist James Stephens, plus classic science fiction from Randall Garrett, J.F. Bone, and Mark Reinsberg. Good stuff.

Here’s the complete lineup—

Mysteries / Suspense / Adventure:

“Hanged By the Neck Until…,” by George Wilhite [Michael Bracken Presents short story]

“The Puzzle Palace Perplex,” by Hal Charles [Solve-It-Yourself Mystery]

“Tethered,” by Marcelle Dubé [Barb Goffman Presents short story]

“Behind a Locked Door,”by Peter DiChellis [short story]

The Just Men of Cordova, by Edgar Wallace [novel]

Science Fiction & Fantasy:

“Free-For-All-Way,” by John Betancourt and Larry Tritten [short story]

“Respectfully Mine,” by Randall Garrett [short story]

“The Missionary,” by J. F. Bone [short story]

“The Satellite-Keeper’s Daughter,” by Mark Reinsberg [short story]

The Demi-Gods, by James Stephens [novel]

Until next time, happy reading!

—John Betancourt

Editor, Black Cat Weekly

TEAM BLACK CAT

EDITOR

John Betancourt

ASSOCIATE EDITORS

Barb Goffman

Michael Bracken

Paul Di Filippo

Darrell Schweitzer

Cynthia M. Ward

PRODUCTION

Sam Hogan

Enid North

Karl Wurf

HANGED BY THE NECK UNTIL…,by George Wilhite

They found what was left of Clyde Harper dragging behind his best horse, Spook. Spook had come home to the Bar H, his white sides heaving, his legs full of prickly pear spikes, pulling the body by a catch rope with the loop tight around Clyde’s neck. The cowboy’s body was scraped raw from the West Texas sand, just a few strands of flesh and hair still hanging to mostly bloody meat, prickly pear pads and a few dead post oak branches hanging off him. Even Cookie, the cocinero, had to look away to keep from throwing up, and he’d seen worse back during the war, the straw boss said, when he’d been a doctor for the Confederacy.

Some of the boys thought there was foul play involved, but Luke, the straw boss, reminded them that Clyde was a South Texas cowboy, and they tied their lariats hard and fast down there, not like them Montana and Wyoming boys that dally rope and can let go of whatever they had on their string if they get in a storm. Since most of the cowboys griping were from up that way, they sort of settled down. But Shorty Terwilliger was adamant.

“Clyde weren’t no dude,” he said, trying to get into Luke’s face, but only making it up to his chest. They called him Shorty for a reason. “How the hell would he ever let the loop get around his neck like that?”

Luke allowed as it might seem odd, but that we’d all had storms before.

“Hell, remember when Red, the wrangler, nearly hanged himself with his stampede string when that sharp limb run its way through his hat? And what about Aubrey Samford when he was chasing that steer and his loop hung on a limb and jerked him off his horse, saddle and all? And Swede Swensen had that roped mama cow hook his horse and run back under him? Caught his arm in that loop and damn near took it off when she hit the end of the rope? That’s why he’s a gimp-armed store clerk in town now. We’ve all had freak accidents happen to us.”

Shorty mumbled something and backed off, heading for the bunkhouse. Nobody else moved. Except for Lane Hollister. He’d been riding with Clyde that morning, but had come back to headquarters at noon, saying he’d lost sight of Clyde as he worked his way down a draw a couple of miles west of the big house. Lane stepped up to Luke.

“I was the last man seen him, he was my partner this morning, and I guess I ought to do the buryin’ of him.”

Luke nodded and Lane went to get the shovel out of the barn. A couple of hands followed him to help. Before they reached the barn, the front door of the headquarters burst open and Sally Davidson, the ranch owner’s daughter, flew across the yard between the main house and the barn.

“Clyde?” she asked Luke.

“Sally, you don’t wanna see…” Luke’s voice trailed off as he couldn’t meet Sally’s frantic eyes. He tried to grab her, but she twisted away and threw herself on Clyde’s bloody body, grabbing the loop off his neck and throwing it clear.

As if on signal, Spook shied away from the action, tripped a little, and fell heavily on his side, his breath coming in long, harsh heaves. Cookie and Luke went to the faithful horse’s head, but they both knew those sounds well enough. Clyde’s best horse died not ten feet from his master.

They buried Clyde—and Spook, at Sally’s insistence—on a hill at the back of the ranch where he and Sally had intended to build a house if he’d ever saved enough money for them to marry. Most of the hands eased up to Sally, tried to say something but couldn’t, then turned, heads down, to trudge back to their horses. Lane Hollister, though, stopped beside her, held his head close to hers and whispered into her ear too low for the others to hear. Then he wrapped his arm around her shoulders and eased her toward the buckboard that had carried Clyde’s body to the grave site. He stopped long enough to say something to Sally’s pa, who nodded, then he helped Sally up onto the wagon seat, climbed up on the other side, and clicked the horses into a slow walk to the big house.

Now, Shorty says it was that very night that he first saw the face at the bunkhouse window, but most of us didn’t see it for a week or so. But by the end of the month, we’d all seen it. A ghostly face at the window when we were bedding down in the bunk house, or a shimmery white rider on a white horse if we were out on the range. We all knew who it was. By the end of the winter, six months after Clyde’s death, the ghost had warned us of a stampede, led Farley Smith back to camp after he’d gotten lost in a blizzard, and shown Luke the way to a lost six-year-old boy. No one ever got close enough to see him for sure, but we all knew he was Clyde.

And if we hadn’t, the ghost made sure of it. Clyde had been a heck of a roper and used to do a couple of tricks with the rope when catching mounts from the remuda in the morning. One of them was to send a coil—a circle of rope—up the length of a catch rope after he’d caught a horse around the neck with the loop. Just as the coil got to the horse’s head, a snap of Clyde’s wrist would send the coil up over the nose of the horse, forming a perfect halter. He sometimes did the same thing except that when he threw the loop, the loop would form a figure eight just before it settled over the horse’s head, one circle of it going around the horse’s neck and the other flipping up around its nose—just another way of “throwin’ a halter” on a saddle horse. Almost every sighting of the white rider mentioned something about throwing a coil down the length of the rope. It was Clyde, all right.

Things came to a head just about the time the grass started greenin’ up. Lane went missing on a Saturday morning, and Shorty mentioned it to Luke. As straw boss, he had to go up to the big house to tell Mr. Davidson. He was back a few minutes later, Davidson storming on his heels.

“Boys,” Luke started, “we don’t know where Lane is and…”

“And I think he’s run off with Sally,” the ranch owner said. “I think that snot killed off Clyde because he was Sally’s best friend. Now he’s run off with my daughter, probably against her will…”

Shorty wouldn’t take that.

“Just a minute, sir. First off, Lane and Clyde was best friends, too. Lane wouldn’t kill him. And—just in case you ain’t noticed—Lane and Sally been seeing a lot of each other these past few months. I don’t think there’s any ‘against her will’ going on there.”

Davidson turned his six-foot, four-inch bulk on the little cowpuncher, his face red with rage.

“By God, boy, I say he killed Clyde and I say he’s taken my daughter. You can go straight to hell. You’re fired.”

Spit flew from his lips as he talked. He whirled on the rest of the crew.

“And that goes for any of the rest of you lily-livered bastards who won’t help me hunt him down.”

He’d probably have lost his whole crew right then if Shorty hadn’t acted first.

“No, sir, you’re wrong. I’ll leave. I don’t much like this place no more. But the rest of boys ain’t got no hand in this. Y’all go along and help him find Lane and Sally.”

He passed a meaningful look to Luke, who nodded. The straw boss understood that it might take the whole bunch of cowboys to contain Davidson if he did find Lane with his daughter. Shorty’s packing took only seconds. He grabbed his war-bag, slung his leggins over his shoulder, and headed for the ketch pen. By the time Davidson had stomped back up the hill to the big house, Shorty had saddled the sorrel mare he’d bought the previous spring and was headed down the road toward town.

He’d only gone about a quarter mile when he turned and cantered back to the bunkhouse as Luke and the hands were stepping out onto the porch, buckling on chaps and old gun belts pulled from war-bags and from under mattresses.

“It’s Lane, boss. Him and Miss Sally are riding up the road from town, all happy and smiling and holding hands. If you want, me and the boys can go meet them and escort them back here.”

Luke saw the wisdom in Shorty’s plan. It would be hard for Davidson to do anything, no matter what his rage, with the whole crew surrounding the couple. He nodded and the boys mounted up to follow Shorty.

The confrontation went better than Shorty had expected. Davidson ranted, but Sally blindsided him when she told him she and Lane had gone to town that morning to get married. She held up the license, signed all legal by the judge.

Davidson huffed and bellowed and clenched and unclenched his fists, but finally he seemed to get control of himself. He pasted a weak smile on his face, hugged his daughter, and said that, of course, this called for a celebration. Then he stalked off toward the house, hollering for Rosa, the cook at the big house, to come a running and motioning for Cookie to follow him. A half hour later, Cookie came back down to tell everyone to head for the big house at sundown for a wedding celebration.

Luke gave the hands the rest of the day off to get ready for the festivities. They drug out the washtub, set it up behind the bunkhouse, and took turns passing the water kettle through the window for a continuous supply of lukewarm bath water. By sundown, they were as shined up as best they’d get, and all eight of them, including Luke and Shorty, headed for the tables set up on the lawn of the house. Davidson had sent Rosa’s four pre-teen sons out on horseback earlier in the afternoon to invite neighbors and friends, who were now straggling in on buggies, wagons, and horseback.

Cookie’s chili went over big, a chill having sprung up as the sun set. Off in the distance, undersides illuminated a brilliant pink, gray storm clouds threatened a possible last-of-spring cold front, maybe a full-blown blue norther. But it wasn’t advancing rapidly and had no effect on the feast, other than to force folks closer to the fire and back to the cooking pots for more hot food. Rosa’s sopapillas and flan with tequila sauce complemented Cookie’s thick, black coffee, although more tequila seemed to find its way into the coffee than it did into the sauce.

It was the wee hours of the morning before things died down and folks, in small groups, started out for home as the storm began to move in. When the last small knot of nearby neighbors left, Davidson drooped his arm around Lane’s shoulders and maneuvered him away from the group of Bar H hands.

Despite the convivial atmosphere, Luke and Shorty shared a glance, split up, and followed the pair as they walked around the corner of the house and toward the corral. They seemed to be in earnest conversation although Luke and Shorty couldn’t hear a word as the blue norther arrived, a chilly wind whipping the conversation away the opposite direction. Davidson gestured widely to indicate the ranch that surrounded them, Lane nodding and taking an occasional sip of the Kentucky bourbon Davidson had supplied him. Lane was a little more than drunk. Davidson showed no signs of insobriety other than an occasional slurred word. Shorty had noticed that the rancher had held a glass of bourbon all night long but hadn’t drunk much of it. The short man’s senses were on alert as the ranch owner and the cowboy turned a corner into the teeth of the escalating wind, the words of the conversation now perfectly clear.

Suddenly, Lane whirled toward Davidson, knocking the bigger man’s arm off his shoulder.

“I don’t think so,” he said, the words spilling out sloppy and hard to understand. “You won’t be able to have it annulled. We’re in love and we’re married. Gonna stay that way, too.”

Davidson dropped all pretense and his bourbon glass, reached into his coat, and pulled out a Colt double-action Lightning. He pointed it at the cowboy.

“You’ll do what I say, boy, or you’ll end up like your friend, Clyde. This is a big ranch. Lots of places to bury a body that won’t ever show up. Hell, if Clyde’s damned horse had kept going in the direction I spooked him toward, his body would have never come back here. Sally would have thought he’d run off, and some hands on some ranch a long way from here would have found a poor cowboy who’d just met a horrible fate. Never figured that pony would make it all the way back here before he died.”

Lane stumbled backward a step.

“You mean…ou?”

Davidson smirked.

“Hell, yeah. I wasn’t going to have my daughter marry some dirt-poor cowboy. Now she went and done that anyway. Best I can do is stop it before it goes any farther. Head for that corral.”

Davidson had motioned with his head to his own personal stable and corral behind the big house. He kept his own high-bred stock there. Lane looked at the pistol and walked in front of the rancher without a word. But the big man couldn’t keep quiet. Even if he had, the strong north wind of the blue norther flung every word he said to Lane back to his two friends following in the shadows, waiting for a chance to intervene.

“Yep, got a little wedding present for my new son-in-law. Nice stud horse for him and his bride to start a herd with. A little wild, but from good stock.”

Lane’s back stiffened as they drew close to the corral. Luke and Shorty trailed along, keeping to cover, wondering what the rancher had in mind. Davidson reached up and untied a fat, soft cotton training rein from the fence as they stepped into the corral. The other end was tied to the halter of a long, hot-blooded black stud that pranced at the end of the rope. The rancher motioned with the gun toward a fancy, new silver-mounted saddle on the top rail of the corral.

“Heck, I even decided to give my daughter’s new husband the fancy saddle I just bought to go with the black. Of course, in his drunken excitement, my son-in-law had to try to ride him, being a top hand and all. Go ahead and saddle him, Lane. Take a ride on your new horse.”

Lane pulled the saddle down automatically, hung the off stirrup on the horn, and eased it down on the black horse’s back. The horse skittered and shifted but the big rancher took a dally around the snubbing post in the middle of the corral, pulling the bronc up tight. Lane got the saddle on and cinched up. Davidson motioned for the cowboy to mount up.

As they stepped up to the bronc, Davidson raised the gun above his head to bring it down on Lane’s skull. At the same instant, Shorty and Luke decided to break from cover, knowing that shouts to distract the rancher would never reach him in a gale like this. There was no way they would reach him in time.

“But drunk like that, well…you know how accidents happen,” Davidson said as he started to bring the gun barrel down on Lane’s head.

But before it could reach the cowboy’s skull, a white form materialized out of nowhere, jerked the rein away from the rancher, and sent it flying toward the descending gun. With the dexterity of supple bullwhip, the rope wrapped around the hand and jerked it skyward, the gun discharging harmlessly into the air above Lane’s head. Lane dropped to the ground and turned in time to see the ghostly apparition send a coil of white rope down the length of the long cotton rein, unwrapping the rope from the hand.

Lane and Shorty both recognized the signature rope trick.

“Clyde,” they both hollered together, the sound lost in the shrieking wind.

Again, the ghost sent the soft cotton rope flying toward the dazed and wide-eyed Davidson. As the coil of rope got close to the rancher’s head, it twisted on itself, forming a figure eight before the two circles closed around the big man’s throat in a hitch, just like the one used by hard-and-fast ropers. The rancher grabbed the rope, but before he could unknot it, the ghost stepped to the head of the black bronc and, with a banshee’s yell, spooked the hot-blooded animal. As the horse leaped away, the rein tightened on Davidson’s neck and jerked him backward with an audible snap. There was one last look of complete disbelief in the big man’s eyes before the blank look of death took over. His body fell soundlessly to the sand of the corral and the rope fell away from his broken neck.

The ghostly form picked up the cotton rein, walked its length to stand by the head of the snorting, frightened horse, then appeared to whisper in its ear. The horse immediately stopped moving, feet spread as far apart as possible, eyes white, ears back. Again the form seemed to whisper in the bronc’s ear, and all tension went out of the animal. It regained its feet, stood squarely, and relaxed its neck, eyes returning to normal and ears pointing toward the ghost. The form moved toward Lane, who was scrambling to his feet near the gate.

The ghost extended the rein toward the young cowboy. Lane reached out tentatively to take it, his hand brushing the ghostly hand in the process. At the touch, the white form brightened almost as white as a lightning burst, then exploded in a shower of misty drops, at the same time as a burst of real lightning broke through the howling wind and raindrops the size of strawberries, cold and stinging from the upper levels of the atmosphere, pummeled the cowboys like watery bullets. Despite the sudden commotion of sound, light, and driven raindrops, the black stallion stood as gentle and meek as a big black puppy full of mother’s milk and waiting for a nap.

The three cowboys didn’t say a word, just looked at each other, then back at the dead body in the corral. Finally, Lane turned to head back to the big house, only to find Sally standing, soaked, three foot in front of him.

“Sally,” he stammered, “I...”

She shook her head at him.

“I heard it all. I saw it. Clyde...”

He threw his arms around her, and she grabbed him back. Despite the cold, the new owners of the Bar H seemed quite warm enough, and off on a ridge a mile away, a ghostly white rider headed toward the next morning’s sunrise.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

A former rodeo cowboy, clown, and bullfighter, George Wilhite is also a former journalist, associate professor, and English department chair. He was an editor of Rodeo News and publisher of Texas Rodeo magazines. He is currently an active member of Mystery Writers of America and a past member of Western Writers of America. Currently, George is a full-time English instructor at Baylor University, where he is also the faculty sponsor of the Writing Guild.

THE PUZZLE PALACE PERPLEX,by Hal Charles

Frida Ford’s heart jumped when she walked into her late Uncle Angus’ boat house and saw who was waiting. Uncle Angus had been the epitome of the fun-loving uncle, always referring to the boathouse as “The Puzzle Palace.” Because he had never married, he had accepted his sister’s kids—Frida, Faith, and Felicia—as his own, inviting Frida’s mother and her three daughters up to the lake most summer weekends to sail, water ski, canoe, swim, but mostly to solve the little mysteries he created. In so doing Uncle Angus had taken the place of Frida’s father, who had died when she was four.

But now Uncle Angus’ death was even more real than at his funeral the previous week. Waiting for her in The Puzzle Palace were her mother, two sisters, and a man she recognized as Angus’ best friend and attorney, Wiley Childs.

“Welcome, Frida,” said the lawyer. “Don’t be upset, but the reading of the will had to come, and Angus insisted on the manner of presentation. My job is to uphold his wishes.”

Wiping away a tear, Frida hugged her mother and two sisters. “I remember some writer saying, ‘There are some things best not thought of,’ but I’m as ready as I’ll ever be.”

“As we all are, dear,” said her mother.

They sat at the black metal table where over their advancing years Angus had fed them grilled food and drinks ranging from Kool-Aid to a cool one and made them learn the parts of a boat.

“Angus’ will is a bit unusual, I have to admit,” announced lawyer Childs as he opened his briefcase.

Frida found herself glancing around the boathouse, noticing all the things Uncle Mort had built over the years. The shiplap-faced bar resembling a powerboat’s aft, the wired canoe hanging above from whose cross-braces dangled three lit chandeliers, the rowboat the three sisters had named the FRI-FA-FEL, even the sailboat where she had won many a Sunday race.

“As you know, your Uncle Angus served for years as a creative writing instructor at the local community college,” continued the lawyer, “so it should come as no surprise that this prelude to his will is composed in the form of a poem.”

“Do we need to accompany your reading with bongo drums?” said her mother.

“Or with a rapper forwarding and reversing a record?” said Faith.

Tuning out the duo’s attempt to break the tension with some humor, Childs cleared his throat and began:

“My stated goal is to thwart.

Don’t become a worrywart.

So drink slowly, don’t guzzle.

The answer to my puzzle

Lights up my last day of sport.”

Immediately, Felicia began to search the bar Uncle Angus had built, arguing, “‘Drink’ … ‘guzzle.’ The answer has to be in his bar.”

The attorney cleared his throat again. “I don’t believe I have explained all the rules. First, you are looking for the actual will, and second, whichever niece finds the will receives half his estate while the other two each partake only of a quarter of the total.”

Faith hurried over to the sailboat sitting on two sawhorses. “Remember how often this boat provided a ‘day of sport,’ a Sunday actually?”

Wiley Childs addressed the mother. “Angus wanted me to assure you he did not forget you, but rather realized your late husband provided you with more than ample resources.”

“I know that,” she said with a smile of remembrance. “I also know that nothing made my brother happier than devising opportunities to test my daughters’ minds.”

Recalling the happiness on her uncle’s face when he concocted especially challenging opportunities—puzzles, word games, crosswords—Frida became quite pensive. Uncle Angus’ prime rule in all his games in The Puzzle Palace had been, “Play fair!” Therefore, even his last seemingly silly limerick must make perfect sense.

Then Frida saw the light, the literal chandeliers dangling from the canoe, and immediately she knew where her uncle had hidden his will.

SOLUTION

For the chandeliers to be lit, wires had to run through the canoe’s hollow cross-braces, which Frida recalled were technically known as a “thwart,” her uncle’s “stated goal” in his poem and a word-play. When she located the will rolled up in the middle thwart, Frida re-divided her uncle’s estate equally among his three nieces.

The Barb Goffman Presents series showcasesthe best in modern mystery and crime stories,

personally selected by one of the most acclaimed

short stories authors and editors in the mystery

field, Barb Goffman, forBlack Cat Weekly.

TETHERED,by Marcelle Dubé

Esther sat on the bench beneath the blood-red maple tree and rested her oak walking stick across her lap. If Beryl showed up, Esther would move the walking stick. Otherwise, she didn’t really want anyone else sitting there.

It was after lunch, and there were children in the park today. Young ones, mostly. She watched them with their mothers or fathers and tried to guess which ones would be in kindergarten or pre-kindergarten. They probably went to school in the mornings only.

Even after being retired from teaching for fifteen years, she missed having young ones around. They had filled her days with life and laughter. And some tears.

She wrapped her overlarge cardigan more tightly around herself. Still only September, but there was a chill in the air and the leaves were ready to shiver down. The park itself was a riot of ferns and late-blooming wildflowers carpeting the ground between sentinel trees.

The bench had been there for over forty years, but she had been coming to this spot for much, much longer. It sat under a maple that had been old when she was young, and gave her a good view of most of the gravel paths snaking through the park. Volunteers took care of the park, though as far as Esther could tell, that care consisted mostly of picking up windblown trash and the odd used condom or syringe.

From dawn to dusk, the park belonged to the day people: kids taking shortcuts, parents and children, old people. But when day fled, the night people came out. The prostitutes, the homeless, the drug dealers.

There were other benches hidden among the trees, but this bench gave her the best view of the spot where Jimmy Bates had died. There, behind one of the six-floor apartment buildings that surrounded the park like some strange, modern-day Stonehenge. Maybe Jimmy had been a sacrifice.

In those days, the park had been undeveloped forest surrounded by new apartment buildings. She and her parents had moved in when she was a baby, and growing up all her friends had been Black like her. Over the years, the population had changed, and today she saw Latino and White, Puerto Rican and Filipino.

After Jimmy died—dead, dead, dead at fifteen—the city bought the undeveloped land and turned it into a park, named for him. As if that made any difference.

His blood still seeped into the ground, even after all these years.

“For Pete’s sake, Esther.”

Esther glanced at Beryl, sitting next to her on the bench, and moved the walking stick. Beryl always appeared when Esther was preoccupied. Today she looked in her midforties, with her dyed brown hair slicked back in a chignon. She’d started dyeing it the day she found her first gray hair. She wore high-waisted jeans and a long-sleeved white shirt with a mandarin collar that buttoned along one shoulder. It was tucked in her jeans, showing off her waist, which was still trim back then.

Esther glanced quickly down at herself, but she was still wearing her sweater over her elderly body.

“What’s the matter now?” she grumbled at her friend.

Beryl took a deep breath and expelled it on a gust. “Everything!” She waved in the direction of Jimmy’s body, so still, so red. “Let it go, why don’t you?”

Esther looked back at Jimmy, but he was gone, replaced by bright red and yellow Icelandic poppies waving their blowsy heads below the pine tree. She blinked and the poppies went back to being naked and dormant.

“It was seventy years ago, you know,” continued Beryl more quietly.

“They never caught him,” murmured Esther.

“Because you never spoke up.”

The muscles of Esther’s chest constricted and, for a moment, she had trouble breathing.

“I was afraid,” she said finally.

Out of the corner of her eye, she saw Beryl nod.

“And you’ve been afraid ever since.”

* * * *

With so many trees bare of leaves, the park was beginning to look naked. Esther wore her heavy wool pants and her duffle coat, with a scarf wrapped around her neck. She felt like a scarecrow dressed up in a field.

“It’s almost my birthday, you know.”

Esther looked around at Beryl. Today, her friend wore her dyed hair à la Farrah Fawcett. Esther’s own hair was completely gray and cropped close to her skull. Beryl looked to be in her thirties and wore bell-bottom jeans and a yellow blouse with a deep V-neck and ruffles down the front.

“I know,” said Esther. Their birthdays had been within days of each other. “You would have been eighty-one. Still older than me.” She glanced surreptitiously down at herself. She still wore the duffle coat. Still herself.

Beryl frowned. “You’re not far behind me.”

Esther grinned. “Eighty.”

“And I was eighty when I died, so there you go.”

There you go, thought Esther. It was dinnertime and the light was fading, but there were still people in the park. A mother pushing a baby carriage—one of those fancy three-wheeled jobs that you could jog behind—and a couple of boys. The boys sat at the only picnic table, at the far end of the park, near Jimmy’s pine. She had seen them before. One youngster, maybe sixteen, with cropped black hair and the other one with red dreadlocks, of all things. He looked about twenty. They were deep in conversation, with the redheaded boy sitting on the table above the other boy.

Jimmy lay where he had died, a bloody corpse that no one ever saw.

“You’ve wasted your whole life obsessing over that boy,” grumped Beryl. “You should have moved away from this damned place.”

Esther could have moved away, but even after her parents died, she stayed in the apartment where she had grown up. Tethered to the place. To Jimmy.

“I was comfortable here.” She shrugged.

Beryl grunted in frustration, a sound she would never have made in life.

“You could have married, had your own children instead of being an auntie to mine.”

Esther glanced at her friend. “How could I marry? You stole the only man I ever loved.”

Beryl stared at her for a moment, and then they both burst out laughing.

The young mum looked around at Esther, and then changed direction, walking quickly away from her.

Esther had dated Jonas first and they had liked each other, but there was never anything serious between them. The moment she introduced him to Beryl, she saw how naturally they fit together, despite the fact that Jonas was Black and Beryl White. She had been Beryl’s maid of honor.

The young black-haired boy got up suddenly and walked away from the other boy, straight to the back door of the nearest monolithic apartment building.

With a sigh, Esther stood, using her sturdy walking stick to balance herself. The wind picked up, swirling the red, red leaves around on the ground.

“Esther,” said Beryl.

She turned to look at her friend.

“Happy birthday,” said Beryl.

* * * *

The rains had been relentless for days. Esther had avoided the park, preferring to stay inside her little fortress of an apartment.

She used to do better in the fall than in the spring or summer. She would never see Jimmy in the fall. He had died on a hot summer day, his blood seeping into the weedy soil like an obscene fertilizer.

But lately, she saw him all the time.

She read or listened to the radio while waiting for the world’s tears to dry up. She had been an only child, and whatever cousins she’d had were dispersed throughout the country. The few friends she’d had had drifted away long ago, disturbed by her need to stay in the apartment of her youth. Her need to stay near Jimmy. All those friends were long gone now, lost to death or dementia. Only Beryl remained, and she was as much a figment of Esther’s imagination as Jimmy was.

Although at times they felt more real to her than the people she saw in the park.

These days, there wasn’t much to fill her days except for housework and baking, but there was no one to share the baking with. And she’d never been one for sweets.

Jimmy had liked sweets, and he’d had the cavities to prove it. He’d been kind to nine-year-old Esther, always saving a candy cigarette for her. She hadn’t had the heart to tell him she didn’t really like them.

When the sun finally came out, she dressed warmly and gingerly descended the two flights of stairs to the back door of her apartment building, emerging into a cold, damp world where the setting sun glinted off anything wet.

Beads of water dotted her bench so she kept going, leaning on her walking stick. The humidity made her knee ache. At least she was thin. Well, gaunt maybe. There wasn’t much weight on her joints.

Raised voices caught her attention, and she glanced toward the picnic table. The poppies nodded their seed pods under the weight of rain drops.

The same boys stood next to the picnic table, arguing. She’d seen them on and off all summer, usually just after sunset and before the night creatures came out. They seemed to be in business together, and she could guess at the kind of business.

Then the picnic table disappeared, and Jimmy stood where it had been. He was gesticulating frantically at Sammy Wildman, who was at least ten years older than Jimmy. She had watched throughout the summer as every night Sammy gave Jimmy a package and Jimmy stuck it in his pocket and ambled away.

Over the summer, however, Jimmy changed. He no longer saved candy cigarettes for her—he barely even spoke to her. So she began to follow him, remaining hidden, and saw him take things from the package and slip them to people he met on the street. They always gave him money in exchange. Then, when there was nothing left of the package, he would return to the trees behind the apartment buildings and hand Sammy the money. Sammy would then peel off a few bills for Jimmy.

But Jimmy seemed to grow more and more reluctant as the summer wore on. One day, Esther approached as close as she dared, hiding behind a tree and clumps of tall grasses, to listen to the argument. Jimmy wanted to stop taking the packages, but Sammy insisted he continue.

Esther stopped walking and stared now, her stomach roiling, knowing what was coming.

Jimmy refused to take the package and pushed Sammy away when he insisted. Sammy slapped Jimmy hard, and suddenly they were on the ground, pummeling each other. Then there was a knife in Sammy’s hand, and he plunged it in Jimmy’s stomach, twisting it upward. Jimmy screamed and curled into himself, blood gushing out of his middle.

Esther clapped a hand over her mouth to keep her screams inside and watched Sammy run, taking his knife with him.

“Something here interesting to you, lady?”

She blinked and Jimmy and Sammy disappeared, replaced by the picnic table. In front of her stood a young man with red dreadlocks. For a moment, she had no idea who he was. Then she realized it was the young man she’d been seeing for months. Behind him, the black-haired boy hovered uncertainly. His eyes seemed to be trying to tell her something.

She turned back to Dreadlocks.

“No, I can’t say there is.” She turned and walked slowly back toward her apartment.

* * * *

“Stay away from them,” said Beryl. Today she was in her twenties, a few years older than when they first met.

Esther sighed and clutched the walking stick more tightly. Stay away from them.

The two boys, Dreadlocks and the younger boy, were back at the picnic table. Dreadlocks sat in his customary place above the other boy and plucked something from his jacket pocket. She couldn’t make out what it was, but she could imagine. He handed it to the boy, who seemed reluctant to take it.

“It’s happening again,” she whispered.

“Then call the police,” said Beryl sharply. “You’re an old woman. You have no business involving yourself in this.”

Esther glanced at Beryl, at her stylish—for then—cut, her black ski pants and lambswool-lined red boots, her camel hair car coat, her red woolen headband, and felt the frustration rise up in herself.

“And do you think they’ll still be here when the police arrive?” she asked. “Do you think they’ll just wait around with the drugs in their pockets? Please.” She turned her shoulder to her oldest friend and studied the two across the park.

She was being unfair and she knew it. Beryl had always been there for her, the sister she’d never had. Just as Esther had always been there for Beryl. They had only ever wanted what was best for each other.

And then she was nine again, hiding behind a tree bigger than herself, shaking in fear that Sammy Wildman would see her, hear her, smell her. But he didn’t. He ran out of the park without ever looking back, leaving Jimmy to bleed his life out on the thirsty soil.

She peered around the tree and saw him lying so still. So silent.

The horror of it overwhelmed her, and she ran back home, never to speak of it. Not to her parents. Not even to Beryl. But in death, apparently, Beryl had learned her secret and now wouldn’t let go.

* * * *

Esther knew which building was the boy’s, and since she never saw him leave through the back door, she reasoned he must leave out the front. She made her way past the side parking lot to the front of his building as fast as her knee would allow, her shoes growing damp in the wet grass. She was grateful for the scarf that kept the wind from sneaking down the back of her collar.

The front of the buildings faced the street, where streetlights reflected wetly on old cars parked like tired nags along the curb. Elms lined the cracked sidewalks, but these were younger trees, barely as old as the buildings. It being suppertime, and cold, most people were inside.

She looked around, but she was too late. The boy was walking swiftly away from her, having entered the building from the back and exited out the front in the time it took her to hobble around the side.

Those two always met at the same time, in the gloaming. Tomorrow, she would wait for him out front, warn him before those long legs could take him away.

* * * *

“You’re planning something, aren’t you?” asked Beryl.

The bench felt particularly hard this morning, as if there was no longer any flesh on her bones to protect her from the world. Jimmy no longer had flesh on his bones. Maybe she was dead too.

She could have gone to him, held his hand as he died. Told the police what she had seen. Made sure Sammy paid for what he’d done.

“I’m not going away, you know.”

Esther sighed and turned to look at her friend…and burst out laughing. Beryl was nineteen and wore bright-yellow hot pants with a matching short-waisted jacket over a neon-pink tank top. And white knee-high, high-heeled boots.

“My word, but we looked ridiculous!”

Beryl grinned. “But sexy.”

Esther sobered and eyed her friend. “That’s what you wore when we first met.”

Beryl nodded.

“At Lorelei Lang’s party,” Esther said. “You were there with Tommy G.” She sighed again, this time from nostalgia. “That was such a long time ago.”

“And I’ve been your friend all that time,” said Beryl gently.

Esther glanced around the park, but it was empty. Not only was it very early—the sun was barely up—but all the leaves were down and there was ice in the puddles leftover from last night’s rain.

“I know you have, Beryl.” She snugged her coat and scarf closer to herself.

“Then please listen to me, and let this go,” said Beryl.

As if drawn against her will, Esther turned her gaze to the dead poppies under the pine tree by the picnic table. Jimmy and Sammy were re-enacting their last argument. She closed her eyes, knowing how it would end.

“Esther...” Something in Beryl’s voice made Esther open her eyes.

Jimmy and Sammy Wildman were gone. In their place stood the black-haired boy and Dreadlocks. The expression on Dreadlocks’s face drove Esther to her feet, her walking stick clutched in both hands.

He pushed a finger into the boy’s chest, but the boy just shook his head and turned away, raising his hands as if to say he was shut of it.

The blade of the knife caught the sun as Dreadlocks raised his fist. Esther screamed, but it wasn’t the boy who turned to look at her. It was Jimmy. Too late, Sammy’s blade found Jimmy’s stomach, and he crumpled to the ground.

She blinked away the tears of horror to find all the boys gone. It was her imagination. Just her imagination. She swallowed back her screams.

“You see?” said Beryl softly. “It wouldn’t have made any difference if you had warned him. He still would have died. And you would have died too.”

* * * *

Maybe she had waited too long.

Esther stood in the shadows at the corner of the boy’s apartment building, where the streetlight couldn’t reach. Night had swooped in like some fell beast, and still the younger boy hadn’t emerged. Was he already lying dead on the ground, his blood feeding the greedy poppies?

Someone rode by on a bicycle, unaware of her presence. She glanced quickly around the street, but there was no sign of Dreadlocks either. What if he waylaid the boy before she could warn him? What if he saw her waiting for the boy and hurt her?

The hard cold seeped in from all sides. Trying to stay out of the wind, she huddled against the corner of the building, watching the entrance to the building with its dim overhead light. Even with gloves on, her fingers were growing numb.

Then a movement caught her eye, and she turned away from the entrance of the building to watch a figure stride confidently down the sidewalk toward the building’s front door.

It was the boy. He was darkness on darkness. Dark hoodie, dark jacket, dark pants. As he passed under the overhead light, he pushed the hood off his head, and she saw that her eyes had betrayed her. She had underestimated his age. He was definitely in his twenties. Without hesitation, he pulled the door open and disappeared inside.

“Damn,” whispered Esther. She had let him walk right by her without even trying to warn him.

At least he was still alive.

She pushed away from the building and hurried around to the back. The smell of rotting leaves struck her as she left the safety of the brick wall to enter the park proper. There were light standards interspersed throughout the park, but not enough to keep the night creatures away. As she hurried toward the picnic table, she grew aware of dim figures on other paths.

Maybe she should have listened to Beryl.

But she was here now. Her foot skittered on a patch of black ice, and only her walking stick saved her from a bad fall. Then the path curved, and the picnic table came into view.

Dreadlocks was there already, sitting in his normal place, and the boy—the man, really—strode up to him. Esther eased herself behind a tree and strained to hear their low voices. They were both turned away from her so she hurried to a closer tree.

“If you don’t listen to me, Steve, you’ll be sorry,” said the boy to Dreadlocks.

Esther risked a glance to make sure of who was talking. The tone of voice confused her. But it was the black-haired boy. Man. He stood looking at Dreadlocks, fists on his hips, chin thrust out belligerently.

“Look, Tyler,” said Dreadlocks, sliding off the picnic table to face him. “I told you the last time. I ain’t doing this no more. I don’t care what you say.”

“How about now?” asked Tyler, pulling a gun out of his coat pocket. “Do you care now?”

And Esther realized she had been trying to warn the wrong boy.

“Whoa!” Steve raised his hands and backed up a step.

“Yeah, that’s right, Steve,” said Tyler. “Are you going to do it now?”

Esther took a deep breath and squared her narrow shoulders. When next she looked, Jimmy was standing beside Tyler, whole, young, a beautiful Black boy with his entire life ahead of him. He watched her intently.

Stepping away, Esther whacked her walking stick against the bole of the maple tree. It resounded like a clap of thunder. Tyler jumped and whirled, waving the gun wildly until his frantic gaze finally landed on Esther. He stared at her for a moment, then scowled.

“Get out of here, old woman,” he said fiercely. “You don’t got no business here.”

“You have no business here,” corrected Esther.

“What?” Now Tyler’s attention was fully on her. She arched an eyebrow at him, aware that Dreadlocks was slowly sidling away from them.

Just keep on moving, she prayed, her gaze fixed on the man with the gun.

“Bad grammar,” said Esther briskly. “‘Don’t got no’ is not grammatical.”

Tyler cocked his head, watching as she stepped closer to him. Finally he remembered his gun and raised it, aiming directly at her. Out of the corner of her eye, she saw Jimmy nod at her.

“Listen, lady,” said Tyler angrily. “You don’t got no business here. Go home before you get hurt.”

Dreadlocks was now among the trees, another shadow in the night. She hoped he would call the police, but she knew better. Nobody would call.

“I’m not going anywhere until you give me that gun, young man,” she said in her best schoolteacher voice.

He laughed and waved the pistol. “Get this,” he said, glancing over his shoulder as if to include Dreadlocks in the joke. Only then did he notice that the other man was gone. He turned a face full of fury back to Esther, but she had crept closer and now swung her walking stick as hard as she could against his wrist.

To Esther’s alarm, his finger spasmed on the trigger, and the gun fired. They both jumped, and the weapon dropped to the hard ground. He scrambled to pick it up with his good hand, and Esther swung the knobby end of the walking stick at his head. He saw it coming and ducked—not that it would have done serious damage had it landed. He stood for a moment, uncertain, half angry, half bewildered. She stared at him fiercely, holding the walking stick in both hands, ready to pounce.

She saw the war in him: attack or run. In the end, with a bemused look on his face, he turned and ran. Esther bent down, mindful of her knee, and picked up the gun. It felt cold and heavy. It was a revolver—she could tell because there was a cylinder—but that was the end of her knowledge of guns.

“Lady,” said a man’s voice behind her, “you’ve got a death wish.”

Esther turned to face the newcomer. One of the homeless ones, unshaven, older than he should be, wearing every bit of clothing he owned. He stayed at a respectful distance.

Esther took a deep, trembling breath and tucked the gun into her coat pocket.

“This is my friend’s park,” she said softly. “I don’t want any more crap here.”

* * * *

She debated long and hard, but in the end, she called the police. They came and searched the park, found the bullet, took her description of Tyler and Steve, and accepted the revolver from her. She wondered if she would ever hear if they found the two boys. Young men. Maybe. If they needed her to testify.

She slept in, exhausted, and had peaceful dreams involving Jimmy and candy cigarettes. It was close to noon by the time she made her way to the bench. The sun was warm on her face, and she loosened her scarf. There seemed to be more people around, not just young parents with their kids but older people too. They all met her eye and nodded.

“You’re a hero, you know,” said Beryl.

Esther looked around to find her friend sitting next to her. Today, she looked like she had when Esther last saw her. Old. Frail. Rheumy-eyed. But with her hair still dyed and in a spiky cut, like a ragged halo. She wore a plaid cardigan over a bright-red turtleneck.

“A hero would have kept Jimmy from getting killed.”

Beryl glanced around. “Do you see him anywhere?”

Esther looked at the dead poppies under the pine tree. No sign of Jimmy or Sam Wildman.

“I think the debt’s been paid,” said Beryl softly.

A weight Esther hadn’t known she was carrying slipped from her shoulders. For the first time in seventy years, she felt light.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Marcelle Dubé writes mystery and speculative fiction novels and short stories, which are featured in anthologies and magazines, including Alfred Hitchcock’s Mystery Magazine, Mystery Magazine, and On Spec Magazine. She received a Derringer nomination for this story. Her work has also been short-listed for the Crime Writers of Canada Award of Excellence, which she won in 2021. Find out more at marcellemdube.com.

BEHIND A LOCKED DOOR,by Peter DiChellis

“Let’s go over your story one more time,” Detective Sofia Cortega instructed the dead man’s twenty-four-year-old stepson. “Just to make sure I have everything right.”

“Again? Of course,” Jared told her. “As I said, I heard sounds of brutal fighting coming from inside my stepfather’s TV room. Crashing and banging and my stepfather grunting and growling like a wounded animal.”

“And the door to the room was locked?” Cortega asked.

“Locked tight.”

Cortega continued. “And when you used your key to unlock the door, a security chain was attached from the inside, so the door would only open a few inches. You peeked through the opening and saw your stepfather lying on the floor, covered in blood. You kicked down the door, which broke the security chain, and you went in.”

The detective paused and consulted her notebook. “You found the room in shambles, but nobody was inside with your stepfather, nobody who could have attacked him?”

“That’s right. But like I told you, two other people went into the room with me,” Jared said. “My stepfather’s nurse caregiver and his sports agent.”

He pointed toward the room’s open doorway and went on. “We all heard the violent brawling. We all went in the room together and saw my stepfather’s dead body on the floor. None of us saw anyone else in the room. It was as though an invisible killer beat my stepfather to death behind a locked door. I tried to revive him but it was too late. That’s when I called 911.”

Suspicious, Cortega took aim at a nagging detail. “Security chains are usually installed on a home’s exterior doors, like a front entrance or back door. Not on a door inside the house, like a TV room. Nothing you said makes sense.”

“Everything I told you is true. And for your information, my stepfather locked his TV room door and attached the security chain for about an hour every night. I think he was watching his old football highlight films and reading past news clippings about himself, reliving his glory days. I guess he felt embarrassed.”

Cortega excused herself to confer with her junior partner Detective Brennan Druckett. Detective Cortega, tall and lean with the bearing of a crack military cadet and the analytic skills of a science professor, towered over the young Druckett, a freckled, redheaded man built like a beer keg.

“Must’ve been a tough confrontation,” Druckett said. “All the room’s furniture is overturned or broken. I guess a pro football legend like Terry ‘Two-Ton’ Tudon doesn’t go down without a fight.”

“Preliminary conclusions?” Cortega asked.

“The evidence says the killer was big and strong, like Tudon. The murder weapon was a heavy wooden chair. I figure the killer swung it by the chair legs and smashed Tudon over the head, hard. Fractured his skull. Blood all over the chair back. Maybe a vengeful player ‘Two-Ton’ hurt during his football days wanted payback. A savage fight to the death.”

“Fingerprints on the chair legs?” Cortega asked.

“Nothing. Maybe the killer wore gloves.”

“And how did the killer exit the room, leaving the door locked and the security chain attached from the inside?”

Druckett dropped his voice to a whisper. “That’s the mystery. There’s no other door and the key to the locked door was in Tudon’s pocket. And all the windows are latched shut from the inside.”

The junior detective held up his hands, as though surrendering. “No chimneys, trapdoors, or secret passageways. No escape routes or hidey-holes anywhere. No way out except through the one door and that door was locked and chained. The evidence says a 300-pound former pro football player was bludgeoned to death inside a locked room by an enormous and powerful killer who disappeared into thin air after witnesses outside the room heard sounds of fighting and knocked on the door.”

“You don’t believe that,” Cortega said.

Druckett shook his head. “I believe we need to find more evidence.”

“Let’s do it.”

The detectives moved on to question two other people who were in Tudon’s home that night, the victim’s nurse caretaker Kaitlyn and his sports agent, Andre. They started with Andre, a gigantic man with a weightlifter’s bulky physique.

“Sports agents on TV look like wimpy lawyers,” the young Druckett said. “You look more like a ballplayer.”

“College ball,” Andre said. “Even played a couple of games against Terry ‘Two-Ton’ back in the day. But I missed my shot at a pro career because of an injury, so I became a sports agent instead.”

“What did you see and hear, before and after entering Tudon’s TV room?” Cortega asked.

“At first I heard loud noises coming from inside the room. Then I saw Jared pounding on the door. Kaitlyn stood right behind him. I saw Jared unlock the door, but the inside chain stopped him from opening it all the way. He kicked the door open and ran into the room. Kaitlyn and I followed him. The room looked a mess. Terry was on the floor. Blood was everywhere. It even got on my shoes and trousers somehow. Nobody was in the room except us.”

“Anything else?” Cortega continued.

“Yes. Cold as it sounds, I saw two greedy slackers whose freeloading just ended.”

“Meaning?”

“I came to Terry’s home tonight to meet with him about his endorsement contracts,” Andre said. “His most lucrative ones expire soon and although Terry wasn’t in bad shape yet, it’s unlikely the sponsors would renew. Everyone recognized his health was going downhill fast.”

The sports agent’s voice hardened. “Without the money from those endorsements, Terry would need every penny he owned just to cover his day-to-day living expenses. So Jared would lose his cushy allowance and inheritance, and Kaitlyn would lose her overpaid job and generous tips. As Terry’s agent, I told him again and again those two were leeches. Maybe he finally set them straight and one of them was angry enough to kill him.”

“Which endorsements was ‘Two-Ton’ losing?” the young Druckett cut in.