2,76 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Black Cat Weekly

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

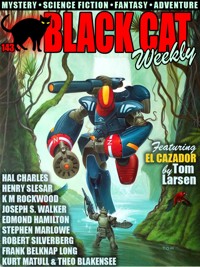

This issue, we have the second of the long-running Dutch series featuring the adventures of Lord Lister (Alias Raffles), as the Robin Hood of England tangles with a jeweler who likes to cheat his customers with fake diamonds and pearls. (This is a new translation and its first appearance in English. We have more coming up.) Plus we have original mysteries by Tom Larsen (thanks to Acquiring Editor Michael Bracken), Joseph S. Walker (thanks to Acquiring Editor Barb Goffman), and K M Rockwood. Plus, of course, a solve-it-yourself puzzler from Hal Charles.

On the science fiction side of things, we have another great lineup, with tales by Stephen Marlow, Henry Slesar, Edmond Hamilton, Frank Belknap Long, and a writer best known for his mysteries, Donald E. Westlake.

Included are:

Mysteries / Suspense / Adventure:

“El Cazador (The Hunter),” by Tom Larsen [Michael Bracken Presents short story]

“New Sheriff in Town,” Hal Charles [Solve-It-Yourself Mystery]

“Sunrise at the Moonshine Palace,” by Joseph S. Walker [Barb Goffman Presents short story]

“Flippin’ Flapjacks,” by K M Rockwood [short story]

“The Punishment of the Jewel Forger,” by Kurt Matull and Theo Blakensee [novelet, Lord Lister (Alias Raffles) #2]

Science Fiction & Fantasy:

“The Passionate Pitchman,” by Stephen Marlow [short story]

“My Robot,” by Henry Slesar [short story]

“The Life-Masters,” by Edmond Hamilton [short story]

“The Red Fetish,” by Frank Belknap Long [short story]

“Meteor Strike!” by Donald E. Westlake [short story]

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 442

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Ähnliche

Table of Contents

COPYRIGHT INFORMATION

THE CAT’S MEOW

TEAM BLACK CAT

NEW SHERIFF IN TOWN, by Hal Charles

EL CAZADOR (The Hunter), by Tom Larsen

SUNRISE AT THE MOONSHINE PALACE, by Joseph S. Walker

FLIPPIN’ FLAPJACKS, by K M Rockwood

THE PUNISHMENT OF THE JEWEL FORGER

CHAPTER ONE

CHAPTER TWO

CHAPTER THREE

CHAPTER FOUR

THE PASSIONATE PITCHMAN, by Stephen Marlowe

MY ROBOT by Henry Slesar

THE LIFE-MASTERS by Edmond Hamilton

THE RED FETISH by Frank Belknap Long

METEOR STRIKE!, by Donald E. Westlake

COPYRIGHT INFORMATION

Copyright © 2024 by Wildside Press LLC.

Published by Black Cat Weekly

blackcatweekly.com

*

“El Cazador” is copyright © 2024 by Tom Larsen and appears here for the first time.

“New Sheriff in Town” is copyright © 2022 by Hal Blythe and Charlie Sweet. Reprinted by permission of the authors.

“Sunrise at the Moonshine Palace” is copyright © 2024 by Joseph S. Walker and appears here for the first time.

“Flippin’ Flapjacks” is copyright © 2024 by K M Rockwood and appears here for the first time.

“The Punishment of the Jewel Forger,” by Kurt Matull and Theo Blakensee was originally published in Dutch as DeStraf van den Juweelenvervalscher in 1910. Translation and expansion copyright © 2024 by John Betancourt.

“The Passionate Pitchman,” by Stephen Marlow, was originally published in Fantastic, October 1956.

“My Robot,” by Henry Slesar, was originally published in Fantastic, February 1957, under the pseudonym “O.H. Leslie.”

“The Life-Masters,” by Edmond Hamilton, was originally published in Weird Tales, January 1930.

“The Red Fetish,” by Frank Belknap Long, was originally published in Weird Tales, January 1930.

“Meteor Strike!” by Donald E. Westlake, originally published in Amazing Stories, November 1961.

THE CAT’S MEOW

Welcome to Black Cat Weekly.

This issue, we have the second of the long-running Dutch series featuring the adventures of Lord Lister (Alias Raffles), as the Robin Hood of England tangles with a jeweler who likes to cheat his customers with fake diamonds and pearls. (This is a new translation and its first appearance in English. We have more coming up.) Plus we have original mysteries by Tom Larsen (thanks to Acquiring Editor Michael Bracken), Joseph S. Walker (thanks to Acquiring Editor Barb Goffman), and K M Rockwood. Plus, of course, a solve-it-yourself puzzler from Hal Charles.

On the science fiction side of things, we have another great lineup, with tales by Stephen Marlow, Henry Slesar, Edmond Hamilton, Frank Belknap Long, and a writer best known for his mysteries, Donald E. Westlake. Enjoy!

Here’s the complete lineup—

Cover art: Tom Miller.

Mysteries / Suspense / Adventure:

“El Cazador (The Hunter),” by Tom Larsen [Michael Bracken Presents short story]

“New Sheriff in Town,” Hal Charles [Solve-It-Yourself Mystery]

“Sunrise at the Moonshine Palace,” by Joseph S. Walker [Barb Goffman Presents short story]

“Flippin’ Flapjacks,” by K M Rockwood [short story]

“The Punishment of the Jewel Forger,” by Kurt Matull and Theo Blakensee [novelet, Lord Lister (Alias Raffles) #2]

Science Fiction & Fantasy:

“The Passionate Pitchman,” by Stephen Marlow [short story]

“My Robot,” by Henry Slesar [short story]

“The Life-Masters,” by Edmond Hamilton [short story]

“The Red Fetish,” by Frank Belknap Long [short story]

“Meteor Strike!” by Donald E. Westlake [short story]

Until next time, happy reading!

—John Betancourt

Editor, Black Cat Weekly

TEAM BLACK CAT

EDITOR

John Betancourt

ART DIRECTOR

Ron Miller

ASSOCIATE EDITORS

Barb Goffman

Michael Bracken

Paul Di Filippo

Darrell Schweitzer

Cynthia M. Ward

PRODUCTION

Sam Hogan

Enid North

Karl Wurf

NEW SHERIFF IN TOWN,by Hal Charles

State Police Detective Kelly Stone glanced at herself in the mirror. A Stetson, gold vest, two six-guns belted around her waist, and boots a size too small. “I look ridiculous,” she pronounced.

“The entire city council thanks you for stepping in at the last minute to play our chief law enforcement officer in Shadow Valley’s Old West Days Festival,” said her sister and councilwoman. Pinning a star on her vest, Krissy added, “I think you deserve a new name. How about Sheriff Wyette Earp?”

“Very funny, sis. Let’s just get this afternoon over.”

Just as Kelly was ready to step outside the tent headquarters, a breathless Mayor Dan Burnside burst in. “Sheriff…detective…Kelly, there’s been a robbery at the bank. Two cowboys in blue polka-dot masks grabbed all the morning’s receipts. The thieves were spotted running into this park, so I had Deputys Rick Peters and June Manymoons cordon it off.”

“So,” reasoned Krissy, “the thieves now walk among us.”

“You sure it was two males?” Kelly pressed.

“Absolutely positive.”

Opening the tent flap, Kelly started counting. “Roughly fifty people inside the yellow tape. Have Rick ask all the women and children to head for that chuckwagon across the street. Offer them a free drink or something.”

When Mayor Burnside returned, he said simply, “Done.”

Kelly held up an evidence bag with two food-covered, blue polka-dot bandanas. “I found these in a trashcan beneath some tacos. Eventually we can get DNA off them, but the perps might not be in the DNA database.”

“What now, then?” said Krissy.

“We do what Wyatt would have done.”

“You going to shoot somebody like at the OK Corral?” asked Krissy incredulously.

“Interviews. But first, Mayor, you can dismiss old Charlie in his wheelchair, Fred Firth in a walking boot, and Jimmy on crutches. That leaves only twelve men.”

“Just like the number of bullets in your Colt .45s,” said Krissy with a smile.

Kelly first interviewed four men in their sixties or above. Since one used a walker, another a cane, and one obviously limped, she dismissed all four. Mayor Burnside had said the two thieves were running, and it had been a while since any of the senior quartet had moved that quickly.

Removing a bushy white mustache from one of the eight left, the detective recognized Ollie Bradley, the local paper’s editor.

“That gent beside me’s Barry Barnett, my ace reporter,” said Ollie. “He’s been with me all day pestering me to try some kettle corn.”

Barry was actually The Gazette’s only reporter, Kelly thought as she dismissed them. That left six suspects. “How many of you are from Shadow Valley?”

Four hands shot up.

“You guys go stand over there with my super-curious and super-sarcastic sister.”

Ten feet away Krissy raised her hand. “That would be me.”

“Where are you two from?” Kelly said to the remaining men.

“Porter Falls, right down the road,” said the taller.

“Me, too,” said the other.

“You two happen to know each other?” posed the detective.

The two men remained silent.

“In case you didn’t realize,” said Kelly, “I’m not really a sheriff. I’m State Police. Porter Falls is in my jurisdiction, and I know it’s a really small town.”

“I might have seen him around town,” admitted the smaller.

Kelly looked them both over. “You guys notice how you’re different from every other male here today?”

“Cause we’re outta-towners?” said the taller.

“Nope,” said Kelly. “You are the only two men in the park without bandanas.”

“We gave them to some kids,” said the smaller.

“I still think she’s lying,” said the taller, “’cause she’s looking for a pair of thieves, and there are two of us.”

Kelly pulled out her cuffs and snapped one ring over each man’s wrist. “Gentleman, follow me. We’re headed for the jail or as they used to call it, the hoosegow.”

SOLUTION

The taller man noted the detective was looking for a pair of thieves. Since Mayor Burnside had told that information to just Kelly and Krissy in the privacy of the tent, the only way they could know that information was if they were the thieves. The bank money was found at the bottom of the trash can where Kelly discovered the polka-dot bandanas.

The Barb Goffman Presents series showcasesthe best in modern mystery and crime stories,

personally selected by one of the most acclaimed

short stories authors and editors in the mystery

field, Barb Goffman, forBlack Cat Weekly.

EL CAZADOR (The Hunter),by Tom Larsen

ONE

July 1976,Guayaquil, Ecuador

ElCazador—The Hunter—waited. He knew the importance of patience. Not that he was afraid he would alert his target. No! His prey that morning was ancient, arthritic, and half-blind, afflicted with a palsy that left his right leg nearly useless.

Patience was important to build tension. The kill would be even more satisfying due to the wait. He had learned that over time, as he perfected his craft. So, he sat, perched on a mound of garbage at the entrance to a narrow alley between a Chinese restaurant and a television repair shop.

The sound of a truck rumbling along the street startled him. Was it the garbage truck already? Had he dozed off and missed his target? No, it was a military truck. Green-clad soldiers of the ruling junta headed back to base as the nightly curfew ended. The garbage truck was still an hour from arriving to pick up this disgusting mess. Throughout the night, street dogs had rooted through it. They tore open the thick black plastic bags, exposing the contents—clumps of rotting vegetables, mounds of decaying rice and sodden paper napkins.

The Hunter ignored or had become immune to the smell. Perhaps it was that the smell had pervaded his being to such an extent that he was now nothing more than a part of this pile of detritus. The idea made him smile, but not in a pleasant way. His thick rubbery lips drew back from his yellowed teeth. Deep creases, almost like scars, formed in his high fleshy cheekbones.

Trash. His mouth formed the word, but the sound was only in his head. That is what they think of us. The Catholics! The Priests!

The Hunter’s prey that morning was just that—a Catholic priest. The old cleric lived in a monastery up on the hill near ParqueSamanes. Every morning in the pre-dawn hours, he took the bus downtown. Getting off at the central bus station, he walked the final twelve blocks to his destination—the end of Calle 49 SE, on the banks of the Río Guayas at its widest spot before it emptied into the Pacific Ocean.

The aged priest had dedicated his final years to ministering to those who inhabited the area. Sailors and fishermen too old to ply their trade, alcoholics, drug addicts, sneak thieves, and prostitutes made up his flock. The few people who knew of his work praised Father Diego Salamanca for his kindness and dedication to Christian principals.

The Hunter knew better. Salamanca was no different than the rest of them. He offered food, shelter, even salvation. But at what cost? To receive this charity, the supplicant had to pledge allegiance to the priest’s god. The priest would say that the poor fool had only to accept his god, but the Hunter knew better on that score too.

* * * *

Rats! They swarmed over The Hunter’s outstretched legs. He remained motionless, but inwardly he seethed. It wasn’t the thought of the disgusting, disease-carrying creatures with black souls touching his body that angered him so. It was their very existence in his homeland that enraged him. There had been no rats in Ecuador—in all South America—until the arrival of the Spaniards in the Sixteenth Century.

Sure, there were tiny mice-like creatures in the tropical forests, but nothing like these spitting, beady-eyed devils. They had stowed away on the sailing ships that arrived periodically in the harbor, and left a few weeks later, laden with massive amounts of gold.

The rats brought disease, but it was the Plague of Catholicism that destroyed the people’s will and enslaved them as surely as the heaviest iron chains.

* * * *

Thud! Scrape! Plop! The soundalerted The Hunter. It was the old priest. The muffled thud of his cane, a gnarled Ceibo limb, followed by the scraping sound of the man’s useless right leg being dragged across the pavement, followed by the heavy plop of his sandal-clad left foot, echoed through the stillness.

Tonight, was the night. The last night before the full moon. The moon itself was hidden by the thick coastal fog, but The Hunter, having spent his entire life in the countryside outside of Saraguro, felt the phases of the moon in his soul.

He scrambled to his feet and crossed the wide sidewalk that looked to have recently been hit by a barrage of mortar shells, and stepped from behind the concrete column that supported the overhanging second story of the building. When he entered the street, he found himself face-to-face with Father Diego Salamanca.

The priest halted in mid-step and almost fell to the ground. He squinted his eyes, attempting to bring this odd-looking individual into focus. The Hunter was dressed all in black. In the manner of dress of his people, his pant legs extended only to mid-calf and the sleeves of his black poncho ended midway between his elbows and his wrist. For everyday wear, his outfit would include a white shirt and a sort of bowler hat. His long hair would be tied back in a single braid.

But tonight, he was The Hunter, not some ignorant campesino. He wore no shirt or hat, his clothes were ragged and filthy, and he let his greasy black hair fall where it may, partially obscuring his face.

“You are Diego Salamanca?”

TWO

“I am Father Salamanca,” the priest said, his voice raspy from disuse.

“Then you must answer for your sins!”

“What?” The priest didn’t understand. “I confess my sins every day,” he said, his voice a little stronger now.

“I didn’t say confess your sins. Anyone can do that.” The Hunter moved closer, bringing his stench along with him. “I said to answer for your sins. The sins of the church.”

“The sins of the church?” Salamanca recoiled at the idea. “Oh, no, son, you see—”

“I am not your son!” The Hunter’s thunderous voice echoed off the concrete buildings.

“But you see; don’t you? The church is an instrument of God. As such She is incapable of sin.”

“Incapable of sin?” The Hunter’s voice rose in volume as well as pitch, until it was more a shriek than a statement. “What about the hundreds of thousands of the Indigenous that you enslaved, forcing them to abandon the old ways and to accept your religion. And slaughtered them if they refused.”

Puzzled, Salamanca replied, “They were given the opportunity to embrace the word of God—the One True Word. Surely you can see that.” The priest smiled for the first time, believing himself to be on firm moral footing. Surely that would satisfy this strange man. His smile faded when The Hunter’s long dirt-stained fingers closed around his neck.

“I will give you one more chance. More than you deserve.” The Hunter took a step back but kept his hands where they were. “Answer for your sins, Diego Salamanca. And for the sins of your church.”

Salamanca slowly shook his head side to side. “I am afraid I cannot do that. As I said—”

The sound that escaped The Hunter’s lips could have been a sigh, or it could have been a grunt of despair. Salamanca would never know because at the same time, he felt the hands tightening around his throat and the filthy fingernails digging into his flesh.

The Hunter threw back his head and sent a silent howl toward the sky, which had now begun to lighten in the east. His body trembled for a few seconds and then he heaved an enormous sigh, his triumph fading away to sadness.

“All you had to do,” he said, “was to admit the harm that you and your church have done.” He released his grip and the old priest slumped to the pavement, his face a hideous mask of pain and astonishment.

THREE

Newly promoted CaptainJuan Ortega was in a foul mood. Those who served with him in Ecuador’s policíanacional would say that was the big man’s default setting. He had only agreed to the one-week training session at the FBI’s South Florida field office so that his wife Teresa could visit her sister. And shop. Teresa loved to shop in Miami. In Ecuador you can buy a multitude of things cheaply, but they wear out or fall apart quickly. Or you can buy good quality products and pay an exorbitant price, because of the tax the government puts on foreign goods. In Miami, thanks to America ingenuity, you could get good quality at affordable prices.

Ortega wasn’t seeing any of that American ingenuity on display in the cramped windowless conference room in which he found himself. The speaker, a stout man wearing khaki slacks and a plaid jacket, gave his spiel in English and a young dark-haired woman translated what he had said for the assembled group—police officers from Mexico, Argentina, Ecuador, and Colombia.

“The study of serial killers is in its infancy,” the speaker said, with more enthusiasm than the statement seemed to warrant. He adjusted his tie and brushed his hand over his blond brush cut. “In fact, my partner and I only recently came up with the term.” He indicated a slight brown-haired man in the front row who wore his hair long with mutton-chop sideburns. He appeared to have bought his suit in the kid’s section.

A hand shot up from the Mexican contingent and the instructor turned his attention in that direction.

“What defines a serial killer?” the Mexican cop said, using flawless English.

“Excellent question!” The instructor smiled, the questioner beamed, and Ortega’s frown deepened.

“The term ‘serial killings’ refers to a series of three or more killings, having common characteristics such as to suggest the reasonable possibility that the crimes were committed by the same perpetrator or perpetrators.”

Ortega caught a few of the words in English but waited for the translator to finish her job. The captain’s voice had been described as ‘a lion’s roar,’ and ‘the croak of a bullfrog,’ among others. One thing was certain. Captain Ortega would be heard.

“Then if a perpetrator, or perpetrators,” Ortega said without raising his hand, “rob a bank or a store, and kill three people. That is a serial killing?”

The instructor waited for the translation, then he smiled in a way that Ortega found condescending.

“No,” he said. “Not at all. Now, if they managed to kill four persons.” He held up four stubby fingers to emphasize the point. “That would be considered a mass murder.” Again, he waited for the translator to finish before continuing. “Do you understand?”

The instructor was already preparing to move on to the next part of his presentation, but Ortega’s foghorn voice boomed out once more.

“I understand,” he said, “that there are no serial killers in Ecuador.”

FOUR

Captain Ortega sat at a table in the hotel restaurant, sipping red wine and enjoying the solitude. Soon enough Teresa and her sister Diana would meet him for dinner, after a day spent laying waste to the shops and boutiques of Miami.

I can only hope, Ortega thought, that Diana doesn’t bring along her husband. Roberto Monsalves was a boor of the highest order. He had escaped Cuba in 1969, surviving for two weeks clinging to a capsized rowboat. He now owned a chain of seven optical stores in Little Havana.

“Come to Miami, Juanito,” he would say after a bottle or two of the good Chilean red that he favored. “I’ll set you up in one of my stores. Assistant manager at first, but…” His wink was truly grotesque, made more offensive by the way he presumed to use Ortega’s nickname, the name that he allowed only his wife to use. Ortega despised the man.

“I am a detective in the national police!” he said one time. When Monsalves laughed and dismissed the idea with a wave of his hand, only Teresa’s firm hand on his forearm kept Ortega from launching himself across the table at him.

* * * *

Ortega unconsciously opened and closed his hands on the table in front of him as he imagined them closing around the throat of his overbearing brother-in-law. He drained half the wine in his glass in one pull. In doing so he noticed his superior officer striding across the room in his direction.

Ortega wasn’t sure if he disliked this man more or less than he did his brother-in-law. Either way it was a close contest. He dipped his head slightly, in hopes that the commander would pass him by without noticing. But he couldn’t hold it for long. Juan Ortega lowers his head for no man! When he looked up, Federico Garcia, the regional commander for Zone Six of the policíanacional, was pulling out the chair directly opposite him.

Captain Ortega was big for an ecuatoriano, nearly six feet tall and weighing nearly eighty kilos. In fact, he had been a standout in the goal for his hometown youth soccer team—LosTigresdeCuenca. A devastating knee injury at nineteen crushed any hopes for a professional career, but he had done all right for himself. After serving his compulsory two years in the military, he returned to Cuenca, married his high school sweetheart, and began his career with the national police. Now at thirty-eight he was the youngest man ever to be granted captain’s bars.

* * * *

“Wasn’t that presentation enlightening, Lieutenant?”

“Captain,” Ortega said. Instinctively he touched his shoulders where the double gold bars would be if he were in uniform. “I’m a captain now. Remember?”

“Yes, yes. Of course, I remember. I pinned the bars on you myself. One of my first acts as commander,”

Ortega grunted and Garcia assumed, incorrectly, that his insulting lapse in memory had been forgotten. Juan Ortega never forgot. Still, the captain was a political animal, and this scrawny little pendejo held the key to his future with the force. He twisted his face into what might pass for a smile.

“What did you find particularly enlightening, comandante?”

“Why, the part where he said that all serial killers either take something from their victims—a trophy—or they leave something behind.”

“Why would they do that? Leave something behind. Wouldn’t that be a clue?”

Garcia narrowed his eyes and stared at Ortega across the table. Was this some of the so-called humor the big slob was famous for?Or was it mockery? That seemed more likely. Well, he would deal with that later. Right now, he was too excited by what he had learned.

“Don’t you see?” he said. “The killer wants to be caught.”

Once again, the commander’s assumption was incorrect. Ortega wasn’t attempting humor, nor was he mocking his superior officer. In fact, he had tuned out the rest of the agent’s lecture and had no idea what his boss was talking about.

“He wants to get caught. The killer.”

“Exactly! The killer is driven to kill, but subconsciously he wants to be punished for his sins.”

“That makes no sense.” Ortega said. “I have arrested thirty-five murderers in my career. The most of any detective in Cuenca, by the way. and—”

“What about the one you didn’t arrest?” Garcia’s sly smile and the way he hunched over made Ortega think of a small grey mouse. But the commander’s taunt hit home all the same. He had been unable to lay hands on the killer of the priest found dead on the steps of the Santa Rosa Cathedral two years earlier. The case was baffling. There were no witnesses, and seemingly no motive. What reason could anyone have for murdering a kindly middle-aged priest who appeared to be loved by all?

Ortega had worked the case in his usual manner; full-on twenty-four hours a day. He interviewed everyone from the bishop down to the old man who swept out the church. But even a high-profile case like this one eventually goes cold. Ortega moved on, and his co-workers quickly learned not to bring it up in the big man’s presence. But here was elcomandante himself, raising the dead, so to speak.

Ortega peered across the table with his little rat eyes behind thick, black-framed glasses, trying to gauge the captain’s reaction. Where Ortega was big and muscular, just starting to go to fat, the commander was small and skinny, even by Ecuadorian standards. His suit, purchased at one of Cuenca’s higher end clothiers, probably cost twice as much as the one Ortega wore, but looked as if it had been tailored for someone else. Ortega’s, made to order by a wizened old tailor who owed the captain more than he could ever repay, molded around his body like a second skin.

* * * *

“That’s right,” Garcia said. “I forgot. You don’t think there are any serial killers in Ecuador.”

“No, I don’t,” Ortega responded. “Ecuatorianos are not that complicated. They kill for three reasons—love, hate, or money.” It occurred to him that the commander had taken his pronouncement during the lecture as something of a personal insult. He wanted desperately for there to be serial killers in Ecuador, specifically in Cuenca, for no other reason that it would look good on his—the commander’s—resume. But the idea that whoever had killed the priest was a serial killer? That was ludicrous.

“With all due respect, SeñorComandante—”

“You say that a lot, you know,” Garcia interrupted.

“Say what, Sir?”

“Whenever you say, ‘With all due respect,’ I know that what follows will be most disrespectful.”

“Well, Sir, be that as it may, I—”

“Juanito!” The booming voice of Ortega’s brother-in-law silenced all conversation in the small restaurant. And there he was, striding toward the table with his hand outstretched, oblivious to the annoyed stares and grumbled complaints in his wake. Teresa and Diana followed.

“I won’t keep you.” The commander stood up from the table. “I see you have company.” He leaned in toward Ortega, his face maddeningly calm and his voice barely above a whisper. “When we get back to Cuenca, you will re-open the priest murder case, and you will stay with it until it is solved.”

“But Sir. I have other cases.”

“No! You don’t.” Garcia held up a bony index finger. “You have one case!” He started to leave but turned back to the table. “You would be well advised to pay attention tomorrow to the second half of the lecture.”

Now Garcia did leave, but as Ortega half-heartedly greeted his guests, he saw him standing in line to pay his bill. He was looking back in Ortega’s direction, a puzzled look on his face.

What is he thinking? Ortega wondered.

* * * *

This is what Garcia was thinking: Thirty-five solved murders. That was Ortega’s record. In seven years as a detective. An average of five per year. The second-best detective had solved four murders in ten years.

The commander knew well that on average there would be eight murders a year in Cuenca. Fifty-six murders in seven years, and Ortega had single-handedly solved thirty-five of them. That was impressive, and Garcia looked forward to using the captain’s talents to bolster his own statistics for years to come. That was, in part, why he had lobbied for the job.

But once he got to know him, something troubled Garcia about his star detective, and now he realized what it was. Ortega only looks at his murder cases as numbers to be entered in a ledger. When he solved one, he entered a figurative checkmark in the ledger, and he moved on. He didn’t care about the victims, about bringing closure or justice to the victim’s families. Another, more troubling notion followed like Summer follows Spring. If Ortega doesn’t care about the victims, only about the result, who is to say that he worries at all if he found the real guilty party. If questioned, Ortega would say with a smirk, “Well, they were guilty of something.” Captain Ortega would bear watching in the future. And Federico Garcia was just the man for the job. Nodding to himself, the commander stepped up to pay his bill.

FIVE

“Veinte-quatro. ¡Lallave!”

The night clerk at the Posada La Perla on Calle Martin Aviles was startled awake, not so much by the words, but by a feeling of dread. The feeling manifested itself as a filthy individual of medium height, dressed in black and smelling like that time the sewer plant backed up into the river.

“Twenty-four, twenty-four.” The key was right there in the box where it should have been, but the clerk feigned confusion to give himself time to think. Was this stinking creature the same man who checked in five nights previously? The well-mannered, neatly dressed Saraguran.

From long experience, the clerk knew that the owner of the inn would react harshly if he called him at this early hour. He laid the key on the desk. When The Hunter picked it up and headed off to his room, the clerk retrieved the bottle of disinfectant from a lower shelf and sprayed it liberally all throughout his domain.

* * * *

The Hunter entered his room on the second floor and immediately headed to the tiny bathroom, where he twisted the knob to turn on the shower. At first a few rusty drops were all that emerged from the mineral-encrusted showerhead, but finally the water flowed clear.

The Hunter carefully removed his sturdy black brogues. He flicked a piece of lettuce and a few strands of noodles—detritus from the night’s stakeout—into the toilet. The rest of his clothes he shed hastily and stuffed into a big black garbage bag that he had brought with him for just that purpose.

Like most budget-friendly hotels in Ecuador, the Posada La Perla offered only cold-water showers. The Hunter stepped under the frigid stream without flinching. He watched as the blackened water swirled around his feet before disappearing down the drain. Four nights he had wallowed in filth, waiting for the right moment to approach Diego Salamanca.

He tore open the small plastic wrapper containing the single thin square of soap that the inn provided. First, he scrubbed his long hair, watching as the black water at his feet turned sudsy and finally clear. He scoured every inch of his body, until the water again ran clear, and his brown skin glowed with a reddish hue. He stood motionless beneath the frigid water until the stream slowed, and finally diminished to a trickle as the other hotel guests woke up and started their morning ablutions.

The Hunter dried himself with the stiff hotel towel and opened the small valise that he had brought with him. He upended the contents of the bag onto his bed—clean socks and underwear, black calf-length pants, white shirt, and the thin black poncho. He dressed, then sat down on the bed and cleaned his shoes with a thin towel.

Crossing the small room, he stood in front of the mirror and expertly tied back his long hair into the single braid that was traditional among the men of his village.

The Hunter took his black hat from the upper drawer of the dresser, examined it for any dust or loose threads, and placed it firmly atop his head.

Before he left, he opened the small window, the only one in the room, and the black bag with his filthy clothes joined the rest of the trash at the bottom of the air shaft.

SIX

Captain Ortega sat at his desk, savoring the cool airy feeling of the office after five days in South Florida, where the air was so thick with humidity that he thought he might drown. His hometown of Cuenca had changed during the thirty-eight years of his life, and not for the better, if you asked him. But the sweet fresh air at 8,500 feet elevation in the Andes never changed and never disappointed.

A cup of instant coffee with hot milk and a plate of chocolate galletas sat in front of him. He was bringing the cup to his mouth after swallowing one of the cookies whole when a slim female officer in a tight-fitting uniform approached his desk. Ortega let his eyes wander all over the patrullera. She responded with a steely-eyed glare.

Ortega sighed. Yet another way that things in his world were changing. “What is it, Peréz?” he said around a mouthful of crumbs.

“ElComandante wants to see you.” Peréz couldn’t help but smile. She knew, everyone in the office knew, that whenever Ortega was summoned to the commander’s office, it wasn’t likely to be to receive a pat on the back for a job well done. Garcia was primarily an administrator, not a cop. He kept all his troops at arm’s length unless he thought they needed a dressing down. In an informal tally kept by Lieutenant Chavez, Garcia’s right-hand man, Captain Ortega was far and away the most frequent visitor to the commander’s office.

* * * *

The commander was unusually animated this morning, which immediately put Ortega on high alert. Garcia even got up from his chair to welcome him, and Ortega noticed that someone had brought out the chair that was saved for special visitors—higher-ups and city officials, not his subordinates.

“Good morning, Juan. I trust you had a comfortable trip back home last night.”

“Yes, Sir.” If you liked leaving Miami at midnight, arriving in Guayaquil at four in the morning, and enduring a harrowing four-hour bus trip through the mountains, then the trip was just fine. “Thank you, Sir.”

Garcia studied his subordinate for a few seconds, trying to remember the last time Ortega had addressed him with such respect. But his mood was too upbeat to dwell on that too long.

“Sit. Sit.” Garcia indicated the guest chair, which was upholstered in a dark green material over a thick slab of foam.

Ortega sank into the chair carefully as if afraid it might collapse or swallow him like one of those flowers in the Amazon that ate insects.

“I assume you took my suggestion and paid stricter attention to the FBI speaker after our little talk.”

“Suggestion?” Ortega had exhausted his stockpile of ‘Sirs’ for one day. “I took it as an order.”

“Yes, and well you should have.”

Ortega’s lips curled in the beginning of a smile, but he damped it down. Garcia was so comical when he tried to be stern.

“As we discussed in Miami, you will re-open the case of the priest who was murdered near the cathedral last year.”

“And as we discussed, Sir!”Ortega bit down hard on the last word, making it plain that it was not a term of respect. “I have a number of open cases that require all my attention.”

“Chavez!” Garcia didn’t raise his voice, but there was no doubt it was a command. The Lieutenant hurtled into the room as if shot from a cannon. Most likely lurking outside the door!

“Go ahead, Lieutenant.” Garcia extended his hand palm up, and Chavez snapped to attention. Ortega listened, inwardly seething while his cases were reassigned—given away—to lesser detectives.

“So!” Ortega stood up so abruptly that Chavez flinched. “Once I solve this murder, then I am free to resume my duties?”

“With restrictions, of course.”

Ortega stomped out of the room.

* * * *

Chavez spoke into the silence left by the big man’s departure. “Will there be anything else, Sir?”

“Yes, Lieutenant. Get that goddamn chair out of here.”

SEVEN

Only The Hunter thought of himself by that name. To the rest of the world, he was known as Abel Fernando Sarango Quispe—Ñano to his parents, Papi to his four children and, to his wife, simply Abe (pronounced Ah-bay).

It took an hour to walk from the posada to the main Guayaquil bus station, where he boarded a blue and white Flota Azuay bus to his home near Saraguro. The six-hour trip took him from the sweltering flatlands, through the ElCajas mountains to Cuenca, and then south on the E35, through Loja Province and finally to the town of Saraguro. With each passing kilometer, The Hunter receded, and Abe came to the fore. He spent the first half of the trip poring over the quechua dictionary. The harsh K sounds and the sibilant whuhs were still foreign to his ears, but he soldiered on, visualizing what the words represented, rather than relying on the clumsy Spanish translations. He knew that he needed to master the ancient language of his people if he was ever to fully understand them and himself.

Like all his classmates at the Catholic school, Abe had learned the passage: Acts 9:18. The scales fell from Saul’s eyes, he saw the truth, and accepted the One True God. He had learned the passage, yes, but it meant nothing to him. It was only the previous year that he stumbled upon a group of elderly Saraguran men who studied the old ways, the way their people had lived for centuries if not millennia. That was the moment when the scales fell from his eyes.

As he learned about the way people lived in harmony with the gods, rather than under the thumb of the Catholic god, he became increasingly angry. He was smart enough to conceal his anger even now after Mama Quilla, the moon mother, had spoken directly to him, and assigned him his sacred mission.

* * * *

There are faster ways to make this trip, but they are, of course, more expensive. The amount Abe earned weaving woolen ponchos and blankets for sale at the local markets was barely enough to feed his growing family. And since he had become obsessed with the study and preservation of the Quechua language and customs, he rarely worked the looms anymore, leaving his wife and the three older children to work long hours. Even Panchito, the three-year-old, was kept busy gathering up the short pieces of yarn that were cut off and fell to the dirt floor of their house. Maria, his wife, would sort them by color and find ingenious ways to incorporate these scraps into her work. Nothing went to waste in the Quispe household.

If the family objected to the increased workload required from them so that he could spend his days on scholarly pursuits, none of those complaints reached his ears. But when the hunting trips started, when he might be gone for a week or ten days, Maria finally objected.

“Abe,” she said when she saw him rooting through the small cedar box where they kept the family money, pulling out wads of paper sucres and handfuls of thin gold coins. “Today is market day. You haven’t left me enough for vegetables, much less a piece of mutton.”

“Meat is toxic to our children’s system, you know. And you should grow your own vegetables.”

Maria’s brow creased. Who was this man, whom she had known since childhood, but now didn’t recognize at all? “But, Abe,” she said, “our people have eaten the flesh of animals throughout our existence. And the ground here is too rocky to grow much. You know that.”

Maria knew that she was courting danger by talking back to her husband, but when it came to feeding her children, she couldn’t stop herself. She stiffened her body, but the blow to her stomach came so swiftly and with such force that she collapsed on the dirt floor, gasping for breath.

Abe picked up his black hat and placed it on his head. He checked the fit in the small mirror and went out the door. The transformation to The Hunter began again.

EIGHT

The restaurant area of the Café Eucalyptus on Avenida Presidente Borrero in downtown Cuenca was an afterthought. It only existed because provincial law required food to be available wherever alcohol is sold. “Available” is the operative word here. By accident, or more likely by design, the chefs at Café Eucalyptus routinely produced the most tasteless, unappetizing dishes in the city.

The bar was another thing entirely. Beers from Germany and Czechoslovakia, and top-shelf liquors from the United States, found their way around the government’s draconian taxes on foreign spirits. From Perú, they came hidden among truckloads of cherries and blueberries, from Colombia in the luggage compartments of international buses. Jack Daniel’s Bourbon, J&B Scotch, and Smirnoff Vodka stood side by side on the shelves with locally distilled Zhumir and Ron Viejo.

Attorneys, doctors, businessmen, and politicians numbered among the patrons who drank at the bar, delighted at the chance to tweak the collective noses of the government they interacted with every day, or in many cases were employed by. Lesser citizens of the city were kept away through an informal embargo enforced by liveried waiters and tuxedo-clad bartenders.

Juan Ortega drank Black & White Scotch, distilled in Quito, Ecuador’s capital city, because he liked the taste. He could easily afford the more expensive liquor because no matter what he drank, the drinks were free. The owners happily paid the price for Ortega’s interference on their behalf. No other policeman, from the lowest patrolman to the commander himself ever set foot in the Eucalyptus.

So, there was quite a stir when Lieutenant Chavez attempted to gain entry at eleven that morning, an hour after Ortega had stormed out of the commander’s office. Chavez was carrying a cardboard file box. A piece of orange tape across the top indicated that the contents were related to a major crime. A piece of blue tape down one side defined the case as being “closed pending further information.”

Ortega sighed and slid off his stool. “I’ve got it, Felipe,” he called to the dayshift bartender.

“Elcomandante says,” Chavez began. The rest of the sentence was lost when Ortega grabbed the box and shut the door in Chavez’s face.

NINE

Abe/The Hunter stood beside the E45 Highway on the border of Morona Santiago Province, with his hand extended out and downward. A Chinese-built Sinotruk carrying diesel fuel began to stop twenty meters before him and finally ground to a halt ten meters past. A pudgy brown arm extended from the driver’s side of the cab and waved him forward. The Hunter picked up his small pack and ran to catch up. The driver, a heavyset man with one drooping eye and a bulbous nose, dressed in grease-stained khaki pants and a faded red T-shirt, was grateful for the company.

“I been on the road for seventeen hours,” he said. “Started out in Quevedo last night. You can help me stay awake. Sí?”

“How will I do that?”

“You can talk to me.”

Abe hesitated. Although he was by nature a friendly if reserved man, he was edging closer to the persona of The Hunter the further he travelled from his home village.

“Okay,” he said finally.

“How far you go?” The driver’s smile showed a few missing teeth. The ones remaining were a pale ochre color.

“Misahualli.”

“Ah, LosMonos.” The driver grunted and made ape-like noises, taking both hands from the wheel to mimic the movements of an excited monkey. The small town at the confluence of the Misahualli and Napo Rivers was a well-known tourist stop for Ecuadorians and foreigners alike. The chief attraction was the large troop of Capuchin monkeys. Driven from their homes by overhunting and deforestation, the troop took over the town. They performed for tourists, begged for treats, and stole anything shiny. Watches, rings, sunglasses, even cameras were fair game.

* * * *

The Hunter was headed to the tiny village of Musuya, another ten kilometers up the Napo River, and deeper into the Jungle, but the driver didn’t need to know that. The Hunter was always careful in his travels. Night had fallen by the time he got out of the truck at Misahualli. He bade the driver goodbye, said a brief prayer to Mama Quilla, and headed for the dock.

Having secured a ride upriver for the morning, he found a spot in some bushes at the edge of the sandy beach. He took a small piece of kapok wood and a ten-centimeter clasp knife from his pack and began carving.

In less than an hour, he had formed the outline of the sun and moon, just like all the rest he had carved. He took a completed figurine from his pocket, the one that he would leave in the outstretched hand of the Jesuit priest. He ran his thumb and forefinger over the amulet, feeling the power of it entering his body. It wasn’t a surge that he felt, but more like a calming embrace of a lover.

When the warm feeling was suddenly replaced by an icy coldness, The Hunter knew it was Mama Quilla bringing him back to reality. He held the finished object up next to the unfinished one—his reason for bringing it out in the first place. To his satisfaction, he found that he had fashioned an exact duplicate. He only needed to smooth the edges and stain it black, and it would be perfect.

The Hunter took a small canvas bag from his pack, placed the unfinished amulet inside and filled the bag with a handful of beach sand. It would take hours of squeezing and rubbing the bag to knock down all the rough edges and prepare it for staining with charcoal and animal fat. He didn’t care. His next kill was still two days away, and he didn’t need much sleep.

TEN

Ortega took the evidence box to a table in the farthest corner of the room. He knew what was in it even before reading the label: Fra. JorgéJaramillo, Fallecido 05 April 1974.

The box was light. Of course, it was. It was his case. His fellow detectives would produce kilos of paperwork filling multiple boxes for the simplest of cases. Capitán Juan Ortega had his own system—relying heavily on confidential informants, hunches, and interrogations that bordered on, and occasionally crossed over to, brutality.

Ortega dumped the contents of the box onto the mahogany table and began to sift through it. A statement from the nun who found the body on the sidewalk outside la Iglesia San José, on her way to morning prayers. DINASED’s report that death had likely been due to strangulation. Ortega snorted as he read the date on the document; 03 Junio 1974. Nearly two months to confirm what Ortega already knew.

He pulled from the box a handful of Polaroid photos. The cheap rubber band that once held them had long since crumbled with age. He smiled as he remembered the young gung-ho patrolman who had taken the pictures, tripping twice on the curb in his excitement. But he had to admit that the kid had done a good job. The first photo showed the front steps of the church, the second, the open metal gate that led to the narrow flagstone sidewalk alongside the church, where the body had been found. Next came a series of three photos of the body in situ—the first one a full-body shot, the second a closeup of the old priest’s face, eyes open wide in surprise.

The third photo caught Ortega’s attention, though he had dismissed it at the time. While the priest’s right arm and both legs were splayed at odd angles, consistent with an unexpected fall, his left arm was perfectly straight and lay at a slight angle from the body. In the open hand lay a small object, no more than five or six centimeters in diameter. It seemed to be a small perfectly round disc setting on a crescent-shaped base. A series of lines and marks had been carved into the face.

No one at the church knew what it was or remembered seeing the priest with it. Most assumed it was some version of the prayer beads they all carried, something that the priest would rub his fingers over while reciting the liturgy.

Although Ortega gave it little notice at the time, the object had found its way into the evidence box. He picked it up and held it in his hand. The object was carved from some kind of wood that Ortega couldn’t identify, and he remembered being impressed by the craftsmanship. It was smooth to the touch, and the lines and markings were consistent in their depth and width. Looking back at the scene from his current vantage point, Ortega could see what he missed the first time.

¡Maldición! I must have been blind. The killer had obviously staged the scene. By extending the priest’s arm out straight he was drawing attention to this piece of wood. Why? He stared at the small piece of wood in his hand for a long time, as if waiting for it to identify itself to him. Then he slipped it into the breast pocket of his shirt. He didn’t know what it was, but he knew someone who would.

ELEVEN

Captain Ortega was about to get up and go in search of Kelbert Bertone, but another commotion at the entrance to the bar caught his attention. A tourist, no doubt, wanting to know why they couldn’t come in and have lunch. The locals knew better. Ortega sighed and heaved himself to his feet. Was there no rest for him, ever?

He was halfway to the door when it flew open, and a river of officialdom poured through the opening. Three patrol sergeants in their starched and creased olive drab uniforms were followed by a pair of junior members of the detective squad in their cheap ill-fitting suits. Two men wearing blue coveralls with the Ecuadorian escudo on their chest followed, each pushing a hand truck before him.

Ortega stopped in his tracks. “What is going on here?” he roared. When the next two men came through the door, he found himself not only motionless but speechless.

Elcomandante, FedericoGarcia was accompanied by a slight, thin-faced individual in a blue serge suit. Julio Castro! The head of the city’s Bureau of Excise Tax Compliance avoided looking in Ortega’s direction, as well he should have. Ortega himself had facilitated ongoing payments from the owner of The Eucalyptus to Castro.

The door from the kitchen opened slightly and a stern grey-haired individual poked his head out. Juan Neira, one of the city’s most prominent attorneys, was the owner of the bar. The name on the title, however, was Oswaldo Pena, a taxi-driver from the Ricuarte Sector of Cuenca. Pena allowed his name to be used in lieu of payment to Neira for getting him off on two drunk driving charges in less than a month.

Ortega caught Neira’s eye and gave him a barely perceptible shake of the head. The attorney nodded and withdrew back into the kitchen. The two men with hand trucks veered off and headed to the small storage room to the left of the bar. They returned in a few minutes with cases of liquor bearing poorly faked Ecuadorian tax stamps. There had been no reason to try to duplicate the real stamps. The bar was under the protection of Capitán Juan Ortega, and that was good enough.

Apparently, not anymore. Ortega caught a smug look on Commander Garcia’s face, but more distressing to him was the look of betrayal on the faces of the staff. The only sympathetic reaction he saw was from Ortega’s second in command. Chavez lifted his shoulders and contorted his face as if to say, “I had nothing to do with this.”

Ortega had long dismissed Lieutenant Javier Chavez merely as Ortega’s lackey, doing whatever it took, enduring whatever humiliation that would allow him to advance through the ranks the quickest. Now he saw intelligence and more importantly an openness, an awareness of his surroundings. Might make a decent detective, he thought. Too bad he’s hitched his wagon to Garcia’s narrow ass.

Ortega piled the scattered papers back into the evidence box, indicating that Chavez was to retrieve the box when everything died down. Receiving a nodded confirmation from the lieutenant, he turned and left the bar through a side door.

As he stepped onto the street, Ortega’s hand went to the breast pocket of his shirt, confirming that the small wooden object was still there.

TWELVE

At dawn, The Hunter boarded the long fiberglass canoe and took a seat near the bow. He was dressed now as a tourist—grey slacks and a blue-and white checked shirt. His long hair was piled up beneath a canvas fisherman’s hat with a wide brim. He regretted the act of stealing the camera that hung around his neck, but it added a touch of reality that complemented his disguise. And he certainly couldn’t afford such an expensive machine.

The transformation was beginning to speed up now. Despite his outwardly casual demeanor, he found himself receding further from the persona of the simple campesinoand becoming The Hunter—the dark avenger.

The Río Napo ran deep and muddy this time of year. Water the color of cappuccino flowed swiftly by, just centimeters below the gunwales of the shallow boat. What would it be like, The Hunter wondered, to just let himself go, disappear beneath the water, and give up this insane quest.

* * * *

The canoe pulled up to the concrete dock at Musuya. The Hunter brushed by the young Shuar maidens who greeted the crowd, trying to draw the people to the various exhibits in thatched roof huts along the dirt trail that led to the town itself. Chontacuro grubs, a protein staple of the Amazon, twitched in agony as they were roasted live over hardwood coals, to the tittering delight of the tourists. The townspeople sold feathered headdresses, poor imitations of the people’s traditional headwear. A muscular young man took pictures of smiling, and in some cases, terrified visitors with a six-foot boa wrapped around their shoulders.

The Hunter despised … no … he pitied these once proud warriors. They had never been defeated by the Incas, nor the Spaniards. Time though, and the relentless march of progress had reduced them to this debasing sideshow of existence.

He was once like them, creating cheap replicas of the traditional Saraguran amulets, for sale to tourists. Then he discovered the Quechua language, the language of his people, nearly eradicated by the conquistadores,