2,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Wildside Press

- Kategorie: Fantasy und Science-Fiction

- Sprache: Englisch

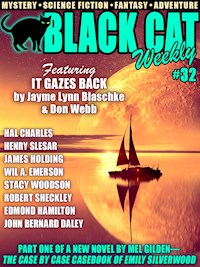

Welcome to Black Cat Weekly #32.

This issue, we have more original stories than ever before. Editors Michael Bracken and Cynthia Ward have brought in new tales by Wil A. Emerson and the writing team of Jayme Lynn Blaschke and Don Webb, and I snagged magazine rights to Mel Gilden’s new novel, The Case by Case Casebook of Emily Silverwood. Mel’s story is a new and thoroughly modern take on the Mary Poppins theme. Wil Emerson has a study on the dynamics of detective partners. And Blachke and Webb’s story (as Cindy Ward put it) “reveals the connections between Nietszche’s abyss, Lovecraft’s god-monsters and non-Euclidean spaces, and Cordwainer Smith’s monsters of subspace.” Wow!

Not to be outdone, Barb Goffman acquired Stacy Woodson’s first story, which won the Ellery Queen’s Mystery Magazine Reader’s Award. And, of course, we have a solve-it-yourself mystery from Hal Charles, a historical adventure novel from Edison Marshall, and a slew of great science fiction stories from such masters as Henry Slesar, and Edmond Hamilson. And a World War II fantasy from Malcolm Edwards.

Here’s the lineup:

Non-Fiction:

“Speaking with Robert Sheckley,” conducted by Darrell Schweitzer [interview]

Mysteries / Suspense / Adventure:

“Insieme,” by Wil A. Emerson [Michael Bracken Presents short story]

“An Eggcellent Equation,” by Hal Charles [solve-it-yourself mystery]

“Paper Caper,” by James Holding [short story]

“Duty, Honor, Hammett,” by Stacy Woodson [Barb Goffman Presents short story]

The Infinite Woman, by Edison Marshall [novel]

Science Fiction & Fantasy:

It Gazes Back,” by Jayme Lynn Blaschke and Don Webb [Cynthia Ward Presents short story]

The Case by Case Casebook of Emily Silverwood, by Mel Gilden [serialized novel]

“Vengeance in Her Bones,” by Malcolm Jameson [short story]

“The Man Who Liked Lions,” by John Bernard Daley [short story]

“A Message from Our Sponsor,” by Henry Slesar [short story]

Crashing Suns, by Edmond Hamilton [novel]

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 1023

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Ähnliche

Table of Contents

COPYRIGHT INFORMATION

THE CAT’S MEOW

TEAM BLACK CAT

INSIEME, by Wil A. Emerson

AN EGGCELLENT EQUATION, by Hal Charles

PAPER CAPER, by James Holding

DUTY, HONOR, HAMMETT, by Stacy Woodson

THE INFINITE WOMAN, by Edison Marshall

BOOK I—India

ONE

TWO

THREE

FOUR

BOOK II—The Novice

FIVE

SIX

SEVEN

EIGHT

NINE

TEN

ELEVEN

TWELVE

THIRTEEN

FOURTEEN

FIFTEEN

SIXTEEN

BOOK III—The Worldly

SEVENTEEN

EIGHTEEN

NINETEEN

TWENTY

TWENTY-ONE

TWENTY-TWO

TWENTY-THREE

TWENTY-FOUR

TWENTY-FIVE

BOOK IV—Krishna the Joyous

TWENTY-SIX

TWENTY-SEVEN

TWENTY-EIGHT

TWENTY-NINE

THIRTY

THIRTY-ONE

THIRTY-TWO

THIRTY-THREE

THIRTY-FOUR

THIRTY-FIVE

THIRTY-SIX

THIRTY-SEVEN

BOOK V—The Dark Mother

THIRTY-EIGHT

THIRTY-NINE

FORTY

FORTY-ONE

FORTY-TWO

FORTY-THREE

FORTY-FOUR

FORTY-FIVE

FORTY-SIX

FORTY-SEVEN

FORTY-EIGHT

SPEAKING WITH ROBERT SHECKLEY, an Interview by Darrell Schweitzer

IT GAZES BACK, by Jayme Lynn Blaschke and Don Webb

THE CASE BY CASE CASEBOOK OF EMILY SILVERWOOD, by Mel Gilden

Case #1: Departures and Arrivals

Case #2: Lost In the Silverwoods

Case #3: Three Doctors

VENGEANCE IN HER BONES, by Malcolm Jameson

THE MAN WHO LIKED LIONS, by John Bernard Daley

A MESSAGE FROM OUR SPONSOR, by Henry Slesar

CRASHING SUNS, by Edmond Hamilton

CHAPTER 1

CHAPTER 2

CHAPTER 3

CHAPTER 4

CHAPTER 5

COPYRIGHT INFORMATION

Copyright © 2022 by Wildside Press LLC.

Published by Wildside Press, LLC.

wildsidepress.com | bcmystery.com

*

“Insieme” is copyright © 2022 by Wil A. Emerson and appears here for the first time.

“An Eggcellent Equation” is copyright © 2022 by Hal Blythe and Charlie Sweet. Reprinted by permission of the authors.

“Paper Caper” is copyright © 1979 by James Holding. Originally published in Alfred Hitchcock’s Mystery Magazine, February 1979. Reprinted by permission of the author’s estate.

“Duty, Honor, Hammett” is copyright © 2018 by Stacy Woodson. Originally published in Ellery Queen Mystery Magazine, Nov/Dec 2018. Reprinted by permission of the author.

“Speaking With Robert Sheckley” is copyright © 1981 by Darrell Schweitzer. Originally published in Science Fiction Review #40, Fall 1981. Reprinted by permission of the author.

“It Gazes Back” is copyright © 2022 by Jayme Lynn Blaschke & Don Webb and appears here for the first time.

The Case by Case Casebook of Emily Silverwood(Part 1 of 4), is copyright © 2022 by Mel Gilden and appears here for the first time.

“The Man Who Liked Lions,” by John Bernard Daley, originally appeared in Infinity Science Fiction, October 1956.

“A Message From Our Sponsor,” by Henry Slesar, originally appeared in Infinity Science Fiction, October 1956.

Crashing Suns, by Edmond Hamilton, originally appeared as a 2-part serial in Weird Tales, August to September 1928.

THE CAT’S MEOW

Welcome to Black Cat Weekly #32.

This issue, we have more original stories than ever before. Editors Michael Bracken and Cynthia Ward have brought in new tales by Wil A. Emerson and the writing team of Jayme Lynn Blaschke and Don Webb, and I snagged magazine rights to Mel Gilden’s new novel, The Case by Case Casebook of Emily Silverwood. Mel’s story is a new and thoroughly modern take on the Mary Poppins theme. Wil Emerson has a study on the dynamics of detective partners. And Blachke and Webb’s story (as Cindy Ward put it) “reveals the connections between Nietszche’s abyss, Lovecraft’s god-monsters and non-Euclidean spaces, and Cordwainer Smith’s monsters of subspace.” Wow!

Not to be outdone, Barb Goffman acquired Stacy Woodson’s first story, which won the Ellery Queen’s Mystery Magazine Reader’s Award. And, of course, we have a solve-it-yourself mystery from Hal Charles, a historical adventure novel from Edison Marshall, and a slew of great science fiction stories from such masters as Henry Slesar, and Edmond Hamilson. And a World War II fantasy from Malcolm Edwards.

Here’s the lineup:

Non-Fiction:

“Speaking with Robert Sheckley,” conducted by Darrell Schweitzer [interview]

Mysteries / Suspense / Adventure:

“Insieme,” by Wil A. Emerson [Michael Bracken Presents short story]

“An Eggcellent Equation,” by Hal Charles [solve-it-yourself mystery]

“Paper Caper,” by James Holding [short story]

“Duty, Honor, Hammett,” by Stacy Woodson [Barb Goffman Presents short story]

The Infinite Woman, by Edison Marshall [novel]

Science Fiction & Fantasy:

It Gazes Back,” by Jayme Lynn Blaschke and Don Webb [Cynthia Ward Presents short story]

The Case by Case Casebook of Emily Silverwood, by Mel Gilden [serialized novel]

“Vengeance in Her Bones,” by Malcolm Jameson [short story]

“The Man Who Liked Lions,” by John Bernard Daley [short story]

“A Message from Our Sponsor,” by Henry Slesar [short story]

Crashing Suns, by Edmond Hamilton [novel]

Happy reading!

—John Betancourt

Editor, Black Cat Weekly

TEAM BLACK CAT

EDITOR

John Betancourt

ASSOCIATE EDITORS

Barb Goffman

Michael Bracken

Darrell Schweitzer

Cynthia M. Ward

PRODUCTION

Sam Hogan

Karl Wurf

INSIEME,by Wil A. Emerson

If the color of her bedroom had been pale blue or a subdued yellow, I would not have given its austerity a second thought. The walls, instead, were painted a cool flesh tone. Light enough, like skin, to envision the veins and tendons of the room’s inner core.

Pale colors used to enhance poetic thoughts? I sensed few sonnets had been written here about someone’s personal life.

The color theme played out on the down comforter and pillow slips on her queen size bed. Two dull blond side-tables were topped with clear cylindrical glass lamps. The only whimsical features anywhere in the room were the white snowflake crystals of various sizes that dangled under bland opaque lamp shades. A hint of flare or a subtle show of dispassion? The bed and tables filled the span of the far wall and caught your eye as you walked into the room. The room itself was large enough for comfort, small enough for intimacy.

On the windowless wall to the left, a porcelain or pearl crucifix about ten inches in height hung above a frameless full-length mirror. Surely the religious token was meant to be viewed each time an image appeared in front of the silver glass. Next to it was a large four-drawer chest. Bleached wood with white knobs, the width about six feet across, stood as a stoic, utilitarian piece of furniture. Nothing had been placed on its surface.

On the opposite wall, floor to ceiling, pale beige linen draperies were drawn together. The dense inner fabric felt like tent material. Were those thick, monotone window covers installed to hide the outside clutter, confusion of the world or to contain the secrets of the room’s occupant?

The absence of a view, the unseasonal warm spring day and a brilliant tangerine sky I’d witnessed shortly before entering the luxury apartment caused me to wonder why this woman, who was now quite dead, had intentionally denied herself the daylight. However, it soon became obvious she wasn’t a stranger of the night.

Darkness and shadows. Secrets, sad songs. One could only guess when it had all started. But it no doubt had come to a sadistic, unnatural end.

One would expect by the woman’s age that this should be a bright, spirited sleeping quarter, as welcoming as the entrance to the modern midtown landmark building with its wide glass door, copper and iron chandeliers, and purple and green ceramic pots filled with ferns and day lilies. The opposite here. So monochromic, it felt anemic.

Obviously, the occupant wanted the room extraordinarily stark. The nude-like quality reflected, in my quick review, constraints and restrictions. Devoid of emotion.

The décor, the atmosphere, told a far more eerie story about a dead occupant than what dispatch had reported when they forwarded the information about the homicide of a prosperous young woman who lived on Lexington Avenue. What I now viewed was more than I had anticipated. The location itself was an area of town where young professionals, lawyers, doctors, stock brokers lived. Safe, sophisticated, and expensive.

Is an address a lifestyle statement or does it lend purpose to one’s life?

I sniffed the air. Waited for one identifying, significant, lone aroma to ignite a clue as to the reason why she died here. What were her likes and dislikes? Pleasures, habits. Wine or whiskey, cigarettes or marijuana, chocolate candy or lemon drops. The physical act of two bodies, love’s peak or the solemn act of loneliness absent, also. To assess the chemical variances in the air, I had to disengage my ultra-keen senses and make a consciousness shift to assess the surroundings at another level of awareness.

I flared my nostrils, breathed deeply. The scent of Dove soap from my morning shower drifted in. Degree antiperspirant also seeped through my mental filter. I wore the brand’s unscented variety but still recognized the distinct properties of its formula: paraben, alcohol, and aluminum chloral hydrate. So I closed my eyes, took several deep breaths, held them to a count of thirty and then pushed out stale carbon dioxide to clear my olfactory epithelium and reset my piriform cortex for unusual odors.

With a certainty, a cognizance not to be ignored, the occupant of this room had done nothing to conjure up a rash of emotions for visitors by introducing trigger scents like musk spray or aromatic candles. Nor were there any antibacterial, alcoholic purifiers to cleanse the air.

I wouldn’t confuse myself, though, or make a rash conclusion until I finished my tried and true routine of identifying what moved through the air besides ordinary hydrogen, nitrogen and oxygen. So I counted again, reset my mind and took another full, nostrils-flaring breath. I mentally catalogued blood, its ferrous, metallic aroma, and put it in the insignificant folder of gray matter. Of course, serum from a victim’s wound is a compelling factor but not necessarily an instructive clue as to why or how the victim died. For instance, if gunpowder lingered heavily in the air from a gunshot it, too, would have been filed and then a search for the weapon would begin. But it was obvious a revolver or pistol had not been the weapon of choice.

I didn’t detect any presence of rancid pharmaceuticals or tainted food particles. If potassium or insulin had been administered intravenously, a distinct body odor would have prevailed and revealed the common side effects of those volatile chemical components. So I repeated my exercise, inhaled deeply, counted to thirty, and discovered to my surprise the room had been cleaned recently with nothing more than bicarbonate of soda and acetic acid. No pine solution, bleach, or commercial cleaner.

Plain old household water, vinegar, and baking soda.

This stale environment was indeed absent of recent sexual activity or biochemical encounters. No vapors of life, no atmospheric, gaseous trail of vitality—no colognes, air fresheners, pheromones of lust, or residual semen. Nothing that spoke of vitality. No cheese, no cracker crumbs, no drinking glasses, no ashtrays or plates of forbidden fruit. A slate washed clean of the nuances of life.

The manner of death had occurred with the aid of a thin, flat, and razor-sharp instrument.

However, there was an odor I distinguished which was nearly as bland as the paint on the wall. This one defining, distinct odor caused my meter to rise. It would help solve the case. Elated, I sighed. To my delight, the odor represented an obvious commercial product used frequently by the public and, more pointedly, I soon discovered, by the deceased.

In this moment of glee, the department Samsung Smartphone vibrated in my pocket. Two options. Pick it up or take the heat for ignoring the call. A few minutes alone wouldn’t make a difference in the resolution of this case.

My partner had a need that I did not share. I’d mutter in Italian, the language I’d set out to learn during the coming year, my dislike for partnerships: “Insieme.”

Working “together” according to protocol often hampered my desire to resolve a case in the manner I wanted.

I backed out of the bedroom, took a few steps in the hall, and then made a complete circle in the middle of the living room I had to shut my eyes because of the startling effect the room had on my senses. A contrast from one room to the other so drastic it momentarily jarred my perception.

Yes, I’d passed through this area into the bedroom earlier but I hadn’t grasped the psychological significance of the sight. Now, after absorbing the pallor of the bedroom and making a methodical sweep, I could study the décor, atmosphere, weightiness of the living area, and make comparisons. My unique way of gathering more pertinent information.

The contrast was a striking contradiction in lifestyle, had a most chilling essence of unhappiness about it, and clutched my soul like a Hallmark sympathy card might have on a grieving widow or widower. How could one make sense of the convoluted dissimilarities?

The front door rattled. Startled, I gasped. Before I could ground myself, Denzel Lewindowski barged through the small foyer. He growled a greeting in his usual manner and then laughed at my reaction.

Lewindowski is regarded as a first class detective but operates in a whirlwind of pandemonium. Size fourteen shoes, arms to his knees, and hands a Yankee catcher would want to transplant. He’s all action, one giant movement. His broad cheeks and bald head lean ahead of his body, as though he’s determined to win the race even if his feet trail far behind. He’s six-four, admits to two-sixty, and can outrun me or any other detective Lewindowski at his game.

If only one time I could accomplish that feat.

Detective Lewindowski and I are a mismatch in the most obvious physical ways. Tall, short. Muscular, lean. Beyond the eye, surreptitiously, instinct is pitted against calculation; cerebral and somewhat compulsive verses plodding with streetwise intimidation. To be honest, Denzel is all collection of facts if you haven’t caught the perpetrator in the act. Slow to make a decision is my synopsis. It’s how he wants to tie facts together that rattles my composure. I identify the root cause and then prove my theory. However, we have narrowed the gap between our methods and mange to work as partners for the common good. We’ve been able to solve various, often hideous crimes. Motive, opportunity, proximity to the murder scene.

A confession works wonders, too. Did I mention there’s a thick layer of brawn that enhances Denzel Lewindowski’s profile and an interrogation skills?

I’m an analyst by nature yet somewhat impulsive. Often a literal concept hits me in the face and I won’t let go of it. Or clairvoyance strikes and I’m not eager to pull back. Besides acquiring Italian as a second language, I’m in the process of learning to abide by the methodical evidence-gathering process.

However, we are in a dead heat as far as solving difficult cases.

The male bonding thing hasn’t happened yet, even though we’ve partnered for nine months. That doesn’t bother me. As I have mentioned, Insieme isn’t my strong suit. Contact between us remains all business. Meals together at any given hour are prompted by the irregularity of the job. Anything more might indicate a need for this partnership.

“You left me high and dry, Partner.” Denzel said with a snarl and rested his meaty shoulder against the wall, inside the mahogany door.

“You were on the can. When I saw the address on the homicide alert, I knew it was only a half block away. I’m only four minutes max ahead of you.” I cut the truth by a few minutes.

“I called. You didn’t pick up. Listen Detective Chadwick Hamilton, I’m the lead here. Got it?”

“My motto: Follow the lead. Certainly glad you found me.” Iced with sarcasm, of course.

“Good thing we’d finished the meal. One damn good burger at Chester’s.” A smile followed.

The day doesn’t hold promise if Lewindowski doesn’t consume a lumberjack-size cheese burger. I prefer Northern Italian cuisine with half a plate of vegetables but never insist on a change in venue because Denzel has seniority and performs well under pressure after he eats a greasy, high-caloric hamburger. Denzel, to his credit, never broods long over our disagreements when he has a full belly. Another character trait we don’t share.

“So the foot officer downstairs filled you in?” I asked.

He nodded, pulled out a tissue and then blew his nose so loud I thought the plaster on the walls would fall off. A crass habit I never encourage by any reaction what-so-ever.

“A long night ahead,” I said. “Haven’t called in the tech guys yet. Gives us a few more minutes before they dust the room with magnetic powder. Did you use the elevator or walk up?” A jab at his ego.

“Walk is for pussies. Ran. All seven floors.” He guessed I’d chosen the stairs. My daily routine to keep my weight at one-fifty.

“So what’s the gig?” he said.

My hand shot out to the left. “Bedroom. One female victim. Nothing’s been touched.” I looked at Denzel’s feet. My intended glare reminded him to contain the debris he’d picked up on the street.

Pissed, his eyes said. He reached in his pocket and pulled out the special-order blue booties. The standard issue was half the size he needed. He gripped his lower lip, waved them at me and bent to pull them over black leather Nikes that looked like umpire shoes but allowed him to move like a running back.

“Okay, Detective Magoo, am I fit to investigate the crime scene?”

He often calls me Magoo, the near-blind, near-dwarf, near-mindless cartoon character who amused him in his youth. The whimsical chap with poor vision triggers a reaction that circulates unconsciously in his mind’s eye. Especially when I get under his skin. So he informs me. He contends it’s harmless, not necessarily derogatory. But it does confirm his aversion to my physical limitations.

Granted, my visual deficits do require refraction lenses. I’m extremely farsighted and solid black frames hold thick lens necessary to balance out distortions.

It doesn’t end there.

Also, my DNA has replicated my mother’s height. Most consider her to be an above-average woman. Five-six. However, for a well-developed, thirty-two-year-old male, it leaves me on the diminutive side. My Fox viewer friends, whom I take with a grain of salt or embrace depending on the subject, state I’m a look-alike for Eric Shawn, media personality and senior correspondent. Half his age, I’m also slight of build, have a rising forehead with thin locks of light brown hair swept from left to right. I consider it a classic look for a man with an IQ of 165 and a burning desire to excel as a New York City detective.

While I’m at it, I should also mention I’ve acquired over the years a neurological sensitivity syndrome. An extreme olfactory meter that works as if I were a human bloodhound. I’ve been tested on several thousand aromas and have not failed a single test. I can’t identify scents underwater or through metal containers like a county sheriff’s favorite lop-eared dog but, I do pick up on more scents than a normal human. While at times it is distressing amongst a crowd of people and in certain public areas, I’ve also been equipped to call to battle a filter system whereas I consciously sort and/or ignore hostile odors at will.

I consider these attributes to be an advantage for a junior detective who aspires to run the entire organization in perhaps ten years.

However, with wisdom and wit to guide me, I realize my goal may not be attained as soon as I’d like. Lewindowski has seniority and has acquired, through practice and cunning, useful, unsophisticated lie detector skills.

Nothing but the truth if questioned by him. He reads eyes and facial lines better than an overpaid PhD with a ten-thousand-dollar machine.

This is but one quality that keeps him on top of the promotion list.

He also has many supporters who admire his bravado-like leadership skills. First at work, last to leave. Well-detailed reports written and delivered on time. Covers your back no matter the situation. Knows the laws. Subscribes to most. Drinks everyone under the table.

Whether he likes me or not, or whether I make Captain or not even if Lewindowski makes the grade before me, I’m confident this job, as a member on the most important blue force in the country, will be mine for a very long time.

No other detective has my innate physical, i.e., nasal, and intellectual skills.

An opinion of mine that keeps us at odds most frequently, though, is my belief detective work is more about gray matter, neurons, synapses, and logical sensitivities than long hours, grit, and paper work. One doesn’t need to go over and over again the same information to draw a conclusion. It is or it isn’t. Denzel does not embrace this philosophy.

So why doesn’t he request a change of partner? A taller, near-sighted, thin-membran-nosed partner might suit him well for routine police work but he or she won’t do anything to advance Denzel’s career. Which explains why I believe at some future date Detective Lewindowski must adopt my viewpoint that the world isn’t all about inches and pounds, muscle mass, or sinew.

Or I’ll make sure he has to find another partner.

“Holy Shit, Hamilton,” Lewindowski calls out from the bedroom where the deceased took her last breath, “This looks like a photo shoot for Crime Magazine. Propped and posed. A scene out of a movie?”

I couldn’t disagree. Nor would I comment.

When he came back into the main area he shook his head as he gazed at the room. “Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs live here?”

“I haven’t looked behind closed doors. She’s alone—I think.”

My head and eyes went to the opposite end of the room. A short hallway in view and then two other doors. One open, one closed. “The officer outside said the rooms have all been cleared.”

As if on cue, Denzel turned left and I did likewise. A small but upgraded, stainless steel kitchen to the left. I backed him up. Closed door, a large closet with a washer and dryer. Next room, a small den, desk of light wood substance, one chair, floor lamp of a metal, silver substance. Nothing tangible on the surfaces. Auxiliary rooms clear.

Back in the living room we made a full circle to take in the accouterments, ornamentations. In contrast to the stark bedroom, color popped out everywhere. Red, green, blue, orange, purple. Two long, striped couches faced each other. One so neon green it hurt my eyes. The other a burning orange. A dozen or more pillows of different shapes and sizes were arranged in an orderly fashion on each couch. Flowers, plaids, stripes, dots, geometric blocks, herringbone weaves.

On the floor, arranged in clusters like toy soldiers but less threatening, were clay and ceramic models of squirrels, raccoons, beavers, chipmunks, rabbits, fox and fawn—everywhere. Not tossed or randomly placed but in a particular order. I sensed none of the animal’s postures were selected for their frivolous nature. Each had a purpose in this most unusual setting.

How did I know this to be true?

Paired. But foxes with fawns, raccoons with possums, chipmunks with squirrels, multiple rabbits and ground hogs. Habitats compatible but not dependent. Environmentally friendly.

All the animals faced the bedroom door.

There were also matched couples. Two rabbits at the end of one sofa, pairs of chipmunks and squirrels under the coffee table. A yellow-tinted Plexiglas table served as a cover for raised heads and snarly smiles. Each creature had squinting dark eyes and pronounced teeth, lips curled in a sneer. Not a cheerful bunch. Not the Alice in Wonderland crowd. Disney on steroids.

Judgmental little bastards, I thought.

Denzel said, “Shit, who set this up?”

“Oh, not necessarily a set up. A lifestyle. Preparation for Noah and the Ark. Perhaps it represents a conflict of interest.”

“Is that a guess or do you know for a fact?”

“No, I’ve never met the deceased to discuss her love for nature or a fear of forty days of rain, but the trappings are indicative of an individual with a cognitive personality disorder. Associative disorder, perhaps. Psychoses are usually multifaceted. Stems from early childhood anxieties. A child of innocence at odds with the whore in the bedroom. The playmates she chooses, as you can see by their sneers, are quite critical. Throw a god-fearing complex into the mix and it suggests she’s prepared the ship if it ever needs to sail. However, she hasn’t appeased her onlookers.”

“Do you have a degree in fiction writing or are you a certified, professional cop? Certainly not a psychologist.”

Some questions are better left unanswered.

“My guess is she’s in her late twenties, childless, and has a long history of sexual promiscuity. A parent who hovers. A demanding figure of influence. If she had been born male, he would have killed his mother by now.”

“Holy shit, where did that all come from?” Denzel slaps his head as he always does when he feels left out. “What am I missing?”

“The order of chaos.”

“Chaos? Well, it looks like a well thought-out, organized murder to me. Some crazy bastard killed this woman. A jealous lover? A John that didn’t want to pay for her cookies? Definitely in a rage, a mad man.”

I had to correct him. “Rage isn’t neat and tidy. What you see is a woman lying on the bed in a perfectly arranged manner. Spread eagle. Golden hair splayed across the pillow. In a virginal white nightgown. The wounds are linear. Straight and to the point. Neck filleted to the jugular. Lower abdomen pierced with a sharp instrument. A symbolic gesture to be sure.”

“A horrible way to die.”

“Obviously she died quickly. My instinct says this is an act of atonement. Old Hebrew style. A sacrifice. I’ll leave it at that. The color of death speaks for itself.”

“Only color in her bedroom is from blood splatter.”

“Yes, red. Red, the color of martyrs. Les Miserable comes to mind. Red the color of angry men? Let’s check her phone lists and the security camera downstairs. I don’t think we’ll have to go far to solve this hideous crime. Even though the victim participated, I believe someone sacrificed this sad, lonely woman for their own new dawn.”

“A new dawn? What? Okay,” he waved me off, “I’m all for checking out videos and Verizon calls but where did you get the hairbrain notion that this is a sacrificial murder?”

“Nothing’s been disturbed in the room. It’s a perfect set up. The victim submitted to a ritual. It appears on first glance to maybe be a sacrament. An offering. I’d venture a guess we’ll find a diary in one of those drawers. Full of confessions about a sordid sex life. And written for the parent who bore the shame of her lifestyle.”

Lewindowski looked at me skeptically. His eyes drawn tight, lips pursed.

The next forty-eight hours were tedious and yet remarkably productive. Lewindowski had found a black book hidden in a pocket sown under the mattress and relentlessly grilled a dozen regular customers on Felicity Marie Blakely’s client list. He barged into offices unannounced, interrupted a group during their splendid lunch at Capital Grill and knocked on a homeowner’s door who happened to be a city councilman.

Alibi of each confirmed and what followed were pleadings for privacy. A gentleman who sat on the bench of the Federal court in our illustrious city, had a handkerchief to his sweating brow when he asked for special dispensation. He was most persuasive with his level of influence. After he dropped the commissioner’s name a few times, I did explain our job had more to do with solving a murder than protecting reputations. But I saw no reason to release this telling list of notable clients to a zealous newspaper reporter who had inadvertently heard the victim was a well-paid lady of the night. Her death would sell papers. Who’s the offender?

Yet a deeper question haunted me. Whose shame was behind the death?

When Jonathon Spurgeon Blakely, father of the victim, agreed to meet with us to discuss the brick wall we’d hit, Lewindowski, to show his compassion, draped one beefy arm around the downtrodden man whose lips quivered and hands shook. As Blakely clutched his own small, tattered black book, I knew it had been read often. And about that very time, I surmised it contained the answer to how Felicity Marie Blakely died.

A father laments even if he’s a man of the cloth. No matter how arduous it is to retain an upper crust about one’s respectable self, hold a jaw tight, this man’s grim hollow eyes and narrow lips conveyed a message all of its own. It’s difficult to interview a bereaved father.

“So when did you last speak with your daughter, Reverend Blakely?” I asked but was quite sure of the answer.

“Months ago. We were not on friendly terms. I’m sorry to say, she had lost her way. I’ve continued to pray for her.”

Lewindowski struck a pose, his shoulders rose and his eyes widened as if the sun broke through in the windowless room. He sighed. “We understand this is difficult. You, a minister. A daughter—with her kind of lifestyle. Did she have enemies? Ex-husband, maybe?”

“Thank God, she never married,” the sad father said.

“And, Reverend Blakely, when was the last time you saw your daughter?” I asked.

“Well, young man, I told you.” He gripped his bible tightly. “We have not spoken for quite some time.”

“Forgive me, my recollection sometimes falters,” I said. “Didn’t you say you’d not spoken to her for months? Perhaps you saw her and didn’t speak. Perhaps on this last, well thought-out encounter with your daughter, you were silent. On a mission. One intentional, short ceremony. A well-planned ritual. The last for unlucky Felicity.”

I’d got right to the point. Would the tactic succeed or fail?

Lewindowski eyed me suspiciously. Blakely sat back in his chair. Although these two men were worlds apart, they were equally stymied by my sudden declaration.

“Righteousness or revenge?” I demanded.

Evidence. Facts. That’s what Lewindowski expected. The moment the Reverend walked into our interrogation room, I smelled the lingering essence of his daughter’s trademark ointment. Paraffinic residual oil. Crystalline and liquid hydrocarbon. A substance than can linger for days. In fact, I knew we could even trace the pharmaceutical company that made the compound. Her brand on his hands. While most detectives would not be aware of the elements of the popular lubricant, it is catalogued in my sensory memory under benign compounds.

“Perhaps you’ll be so kind as to allow us to swab your hands. A simple process. No pain involved,” I said.

Reverend Jonathan Spurgeon Blakely’s smug look turned sour. Eyes tight, lips in one thin line.

“Just what do you think you will gain by pressing for this information? My daughter, a Jezebel, had no shame. I prayed for years for her to repent. Throw her out the window, to be eaten by stray dogs? God would have condemned me.”

“Prayers work wonders,” said Catholic Lewindowski, still trying to piece my summation together.

“And then, she called three days ago. A miraculous transformation. She wanted to give herself to the Lord. I listened to her pleas.”

“Are you trying to mislead me? You asked what would we gain? We will gain evidence that you killed your daughter.” My eyes never left his cold, emotionless glare.

“Surely you’re not accusing this respected minister of murder,” Good cop Lewindowski said.

“No, I’d only accuse a cold blooded killer,” Bad cop responded.

We waited. Two detectives. Unique skills. Determination: first page in the Handbook for Justice.

“I wanted her to be happy, be successful. Felicity, named after the saint of ancient Rome. I taught her to seek great things for herself. Marie, a sacred name. I taught her to pray every day. Live a sinless life. If only she had stayed pure after her baptism.”

“Felicity died from multiple wounds, to her throat and abdomen.” I said with little compassion. I shook my head. The idea so preposterous.

He blinked, raised his head. “Thank God, her mother passed to heaven before our daughter wed the devil. It saved my wife endless shame.”

“You killed your daughter,” Lewindowski spoke with a parishioner’s heart.

“Finally, after all these years, Felicity agreed to cleanse her soul. It was a Eucharistic ritual. Nothing more. There was no sin.”

“You conducted the ceremony?” I asked. “Figliadibabbo. Inseime.”

“I prayed for God to show her the way. And then we prayed together.” Anger formed in his steel eyes. “I had waited so long. My prayers gone unanswered but I did not murder my daughter.”

“Patience is a virtue, Reverend Blakely. And sometimes God answers with a no.” Denzel spoke. His tone reflected reconciliation.

“Aver voce in capitolo,” I said in my usual gritty tone. This seldom used Italian phrase fit the somber occasion. A man that wanted control of a matter should never be taken lightly.

“I couldn’t let her end up in hell,” said the shallow man. “Yes, she finally welcomed the light—after years of moral decay. My last sermon got through to her. An eternal life full of grace and beauty awaited her. Then we worked to eradicate every essence of the terrible activities that took place in her hell hole.”

I surmised he meant they’d cleaned her bedroom, took away her devices that aided her income, with his holy water combination of distilled water, baking soda, and vinegar.

“In a dark moment, she realized the past would always haunt her. Her soul would never be clean unless she offered herself to God.”

“Your sermon or brain washing? Damn it, how could you miss the message in your bible about vengeance?” asked my partner.

Denzel shared later that he suspected the minister had played a role in his daughter’s death when my first question caused a rush of autonomic reflexes on the face of the ruthless man. Pearls of perspiration rolled down the minister’s forehead. His lips turned pale and those heartless eyes flared with specks of red.

Denzel knew, but didn’t want to believe. Denzel has two daughters of his own.

Of course, it took more than Denzel’s unique intuition and my superior mental attributes to prove our case. Facts are also required by the District Attorney’s office.

Reverend Blakely had little fear, with his rule book clutched in his hand and self-assurance strong he would be protected by his belief, he consented to the laboratory test. The lab tech told me the results would be available in less than an hour when I relayed what I knew would be found amongst the obvious skin cells.

If you know what you are looking for, it can be found.

Self-confidence reigned and the results of the finger swab proved my nose was, indeed, accurate. The compound used frequently by the reverend’s daughter, the woman of the night, is so benign one hardly thinks to scrub it away.

Vaseline. Pure, one-hundred percent Vaseline. Found in many bathroom cupboards but to a lesser extent than what Felicity routinely used.

One could argue that her father picked up the residue in her apartment on a visit. We had no weapon and he’d escaped detection on the video cameras. We had to add another hour to the inquisition and his story didn’t change. She had performed the ritual, he said.

“Murder by any other name is nevertheless deadly. No matter the intention, whether draped in one’s core religion or driven by violent intent, the perpetrator must abide by civil laws or pay the piper,” Denzel said and then leaned across the table with his broad hands spread out.

I had nothing more to contribute and left the room.

* * * *

When Lewindowski called me back into the interrogation room, I gave my esteemed partner a deferential bow. Persistence and polished interrogation skills had led to a confession. Signed by the man who still wore a righteous smug on his face.

We almost high-fived in the hall moments later. A stretch of the imagination as I leapt into the air.

We were called into the Commissioner’s office the next day. Commissioner Beckett reminded me of a man for all seasons. He’s straight-backed, maybe five-eleven, slim, red hair stiff like a Brillo pad and has pink cheeks. Married, seven kids. He plays the drums and reads voraciously. His brood, I’ve been told, have few boundaries at home. Chaos runs amuck but they all play string instruments. Hope for the future. How he has time to juggle two lives remains a mystery.

He offered his clean hand. A firm grip conveyed a job-well-done. No frills on this job. He’s a man of few words but his messages keep the walls of this century-old building standing. Follow the rules, no elaborate displays. It’s all about the team. There’s no room for grandstanders. The distinguished leader didn’t invite the mayor to his lone-man, five-minute press conference where he highlighted the department’s record of solving difficult cases. Lewindowski and I accepted his congratulations with grace. All in a day’s work the general tone.

The following day, after a variety of follow-up tasks were completed, Lewindowski suggested we alter our meal choice. He drove our sedan in the opposite direction of his favorite diner. When he stopped in front of Abbocato’s, a five-star restaurant on Hudson Drive, my eyebrows nearly touched my hairline. The day had ended well.

“By the way,” he said as he sipped a dark red semi-sweet wine, “what the hell was that Etalian you spoke to the preacher man all about?”

His question caught me by surprise. I thought he hardly took notice of my alternative mode of communicating a declarative point.

I paused, surveyed the elegant dining facility. Earth-tone stucco walls, vineyards on canvas, white tablecloths, fine silk draperies of red and gold surrounded us. More beauty found in the aromas. Few saturated fats, no artificial preservatives. Fresh garlic, fennel, arugula with its hickory tinge, fresh semolina noodles, and my favorite Parmigiano-Reggiano. And then, I happily filtered out the few other mundane odors carried in by the public.

Denzel remained patient as he waited for my reply.

“Well,” I said as I savored the taste of my dry red Tommasi Amarone, “don’t we all like to ‘have a say’ in the matter? The father, babbo, couldn’t resist dominating his daughter’s, figlia’s life.”

At that point I knew my partner had arranged this dinner as a peace offering. An acknowledgement of my contribution to the investigation. “Aver voce in capitolo.”

“Aver voce in capitol,” I said with a smile. “A say in the matter.” It would now be necessary to forego the other phrase I’d used as a play on words, my form of resentment. Insieme. Together.

This hideous crime would not have reached a satisfactory outcome without Denzel’s doggedly nature. Lewindowski and I were a team. Intellectual acuity recognized. Persistence, instinctive guile equally important. Yes, I would give up my haughty superiority; more than willing to work “together.”

“Allanostra salute,” I said with a grin and raised my glass to my partner.

AN EGGCELLENT EQUATION,by Hal Charles

Peeking around the corner to see her grandmother opening the refrigerator door, Julie realized how much she loved visiting her “Gram,” especially on Easter mornings. “What’cha you doing, Gram?”

The tall, slim woman looked up with a smile as she placed a Styrofoam carton on a top rack. “Oh, just putting away some eggs I didn’t dye for today’s community egg hunt.”

A retired high school math teacher, Julie’s grandmother volunteered for community events throughout the year, but the egg hunt was her favorite.

As long as she could remember, Julie had loved egg hunts too, but the ones she had at her grandmother’s on Easter were unique. Gram’s only grandchild, Julie enjoyed a special place in her grandmother’s heart, and every Easter Gram dreamed up a “hunt” in which she hid a beautiful porcelain egg passed down in her family and supplied Julie with clues to its location. The hollow egg always contained a special Easter gift for Julie.

“O.K., Gram,” Julie said excitedly, “where are the clues?”

Gram pointed to a slip of paper on the kitchen table. “This year’s hunt is challenging, but I have confidence in you.”

Julie scooped up the paper and read the hand-printed message: MATH CAN BE COOL; JUST REMEMBER MY AGE. How many times over the years had Gram uttered her favorite expression, “Math can be cool,” as she tried to pass on her love for numbers to her granddaughter?

The wheels in Julie’s head started to turn. Her grandmother had celebrated her 75th birthday a few weeks earlier, so Julie tried to think of possible associations with the number 75. Every year Gram’s clues became a little more difficult, but that was the fun of the hunt.

Remembering that one of her grandmother’s favorite pastimes was playing bingo at the community center, Julie said, “Didn’t you tell me that a standard bingo game contained 75 balls from which to choose?”

“That’s correct, dear, but I don’t have a blower or cage around the house, so you’ll not find your egg nestled among a bunch of bingo balls. Think again.”

Julie pursed her lips. “Mom was born in 1975. Do you have any—”

“We don’t have much time before we have to head out for the park, so I’ll tell you the clue has nothing to do with your mother’s birth.”

Julie’s mind was doing flip-flops as she tried to come up with a solution involving 75 in some way. Could it have something to do with the year of Gram’s birth 75 years earlier? Perhaps it involved a location 75 miles from their town. Or…

“Don’t forget there are two parts to the clue,” Gram said, obviously enjoying her granddaughter’s quandary.

“Wait a second,” said Julie, a light seemingly flashing before her. “75 and math.” She raced over to the bookcase in the living room and excitedly pulled a book from the shelf.

Noticing the smile on her grandmother’s face, Julie flipped through the pages of Enjoying Numbers, the colorful book Gram had used to introduce her five-year-old granddaughter to math, till she came to page 75. In bold letters across the top of the page she read, “Addition.” That was just the information she needed.

“This year’s clue was more challenging all right, Gram, but I think I’ve ‘cracked’ it,” Julie said with a laugh. “If I add 7 plus 5, I get 12, a dozen.”

“So,” said Gram, her smile widening, “where will we find the egg?”

“Math really is cool,” said Julie, heading for the kitchen.

Where did Julie find the special Easter egg?

Solution

Julie remembered her grandmother placing the carton of eggs in the refrigerator where they would stay cool. Sure enough, one of the eggs was porcelain, and inside, Julie found Gram’s beautiful cameo ring that she had admired for years. How could Gram possibly top this year’s Easter surprise?

PAPER CAPER,by James Holding

Howard Slack had long since given up any hope of becoming a second Philip Marlowe or Sam Spade. As far as he was concerned, the private detective business was strictly a bummer. After eking out a bare living at it for twenty years, his clients usually petty criminals and their women, his detective work the gathering of unsavory evidence to be used for blackmail or divorce, he had no illusions left.

Nevertheless, when Doris Lasswell walked into his shabby office, he rose from his swivel chair, bowed across his desk toward her and said politely, “Can I help you, Miss?” He was desperate for business.

The girl was maybe fifteen years old, Slack guessed. And she looked not at all like a potential client. More like a typical sloppy high-school kid with her faded blue jeans, dirty T-shirt, thong sandals, long mouse-colored hair, aggressive chin, and uncertain expression. A typical high-school girl except for one thing: she had a black eye—a beauty, just reaching yellow-and-purple maturity. Definitely not a potential client. But since one of the few things Slack had learned for sure during his sleazy career was that appearances are usually deceptive, he continued to smile warmly at her until Doris said. “Are you Mr. Slack?” She jerked a thumb over her shoulder at the chipped lettering of his name on the office door.

“I’m Slack, yes. What can I do for you?”

She hesitated. “I’m not sure you can do anything for me.”

“Neither am I,” Slack said, “until you tell me what your problem is. And whether you can pay me for my help. You have any money?”

She shook her head.

Slack sighed. He sat down in his swivel chair and gestured wearily toward the door. “No freebies here, Miss. I’m sorry.”

She didn’t move.

Slack said, “Do you understand what I’m saying? You got no money, you get no detective. So out. I’m a busy man.”

The girl came to a decision of some sort. She swallowed and said, “I think you’ll be interested in what I can tell you, Mr. Slack. Even if I have no money to pay you with—yet.” She added the last word softly.

Slack felt a small spark of interest begin to glow. “Sit down then. And tell me who you are. And what you think I’ll be so interested in.”

“I’m Doris Lasswell.” She sank bonelessly into the straight chair on the other side of Slack’s desk. “And I think I know something about a local crime.” When Slack didn’t respond, she went on. “If you’re a detective, you’re supposed to be interested in crimes.”

“That’s right,” said Slack. “But if you already know about this crime, whatever it is, you don’t need a private detective, kid. Go tell the cops about it, not me. I’ve got a living to make.”

“I don’t want to tell the police.”

“Why not?”

“Because if I told the police they wouldn’t help me with my problem. But if I tell you maybe you will.”

“What’s that mean?”

She swallowed again and gazed rather desperately around his cramped, undusted office. Then she said in a small voice, “Maybe I better tell you about my problem first.”

“I can see your problem from here,” Slack said. “Your boyfriend give you that beautiful shiner?”

She ran a finger tenderly over the swollen discolored flesh around her eye. Her lips pulled down. “Not my boyfriend, no. I don’t have one. My father.”

“Your father? Well, well.”

“He’s not—not nice to me. Mr. Slack. Not like he used to be. Not like a father at all, really. He has a few drinks down at Casey’s Tavern, and—and usually ends up doing something like this to me.” She touched her eye again.

“Why?” Slack asked without much interest.

Doris scraped her sandal over the thin place in the rug at her feet. “Well, my mother left us a year ago, and my father was surprised and mad—he still is—and I suppose he tried to take it out on me, you know? Anyway, I’ve got to get away from him. Mr. Slack. As far as I can. I can’t stand living with him anymore, he’s really impossible.” She broke off miserably.

“Never mind,” Slack said. “So you want to get away from your old man because he beats you. I can understand that. Now what’s this crime you’d rather tell me about than the cops?”

“I think it could involve a lot of money,” Doris said slowly, “for someone. A lot of money, Mr. Slack. But if I told the police about it, nobody would get any of the money, do you see? So I thought I’d tell you and maybe—” She let the sentence trail off.

“You thought I might latch onto this money and give you enough of it to get away from your father, is that it?”

“Oh, yes,” Doris breathed. “That’s it, Mr. Slack. Exactly. Would you?”

Slack leaned back in his chair. He was impressed despite himself by the girl’s earnestness. Yet there had to be a joker in her story somewhere. For this ugly beat-up teenager couldn’t possibly know any secret information about a lot of loose money, could she?

“I can’t promise anything, Doris,” Slack said carefully, “till I know a little more about the setup.”

Her battered face showed relief. “That means you’ll help me?”

“Maybe. Tell me about the money.”

“Well,” she said, “my father and I live in Fernwood Mobile Home Park south of town. Do you know where that is?”

“Sure. Out past the phosphate plant across from an A&P store.”

She nodded. “That’s where my father works, the phosphate plant. Anyway, our next-door neighbor in Fernwood Park is an old retired man named Landry. He has one of those huge double-size trailers that take up two whole lots and have almost as much room in them as a regular house, you know?”

“Never mind about the trailer,” Slack said.

“But that’s where I saw the crime, Mr. Slack. So I have to tell you about it.”

Slack sighed. “O.K., tell me about it.”

“Well, Mr. Landry lives in half of his trailer and uses the other half as a sort of office and laboratory. He was a chemist for a paper company before be retired, and he still likes to fool around with experiments and things, he says. Anyway, he’s been real nice to me the few times I’ve talked to him. He’s only lived there for six months or so.” She paused. “When I do my homework after school, I sit beside a window in our trailer that faces the window in Mr. Landry’s laboratory. His window’s usually closed and has thick curtains inside, but last Thursday it was very hot, and Mr. Landry’s window was open and the curtains inside were apart a little way and I could see in.”

“What did you see?”

“Mr. Landry was in there, running some kind of a machine.”

“A machine?”

“Yes, a paper-cutting machine, I guess, with a little spout on top that kept dripping all the time. Anyway, Mr. Landry was cutting up a long narrow roll of paper with his machine into little pieces about an inch square, or maybe two inches. Then, every once in a while, the machine would gather up a bunch of the little squares and stick them together somehow, like in pads, you know?”

Slack was bored. He said impatiently, “This is a crime? For a retired paper maker to be making his own memo pads?”

Doris nodded vigorously. “Wait. After Mr. Landry finished making up a lot of the little pads, there was one square of paper left over. And Mr. Landry picked it up and held it out in front of him, like he was proposing a toast or something, and then he laughed out loud and said, ‘Here’s to the machine that will make me rich. Time for a little celebration, Landry, don’t you think?’”

Slack looked puzzled. “So he’s doped out some kind of machine. That’s no crime.”

Doris rushed on. “But listen. Do you know what Mr. Landry did to celebrate his new machine?”

Slack shook his head. “What?”

“He ate that little square of paper! He put it in his mouth and chewed it up and swallowed it! I saw him!”

Slack froze.

Gravely, Doris nodded. “I’ve seen it at school,” she offered by way of explanation. “Some of the kids do it.”

Slack drew a deep breath. After a moment he said quietly, “How many other people have you told about this, Doris?”

“Nobody but you.”

“Are you sure?”

“Of course I’m sure.”

“Then who sent you to me?”

“Nobody. I just decided for myself, because of what I heard about you.”

“What was that?”

“That you’re crooked. That you falsify reports to clients. That you’re connected with the dope traffic. That you’d sell your own grandmother for money!” Doris looked him in the eye.

Slack frowned. “Where did you hear that?”

“One of my father’s friends is a deputy sheriff. He came to our trailer last night to have supper with my father. While they were drinking beer I was cooking their hamburgers in the kitchen, and I heard my father ask him about who would be a good private detective to hire to try to trace my mother and make her come home.”

“Oh,” said Slack sarcastically. “I get it. This smart-aleck deputy recommended me, I suppose. Because I’m crooked and falsify reports and so on?”

Doris regarded him out of her good eye. “No, Mr. Slack,” she said. “The deputy told my father any private detective in the yellow pages would be fine except you. Because you’re crooked and falsify.”

Slack held up his hand. “Please.”

“You believe me, don’t you? I thought that if the deputy was right, that you’d do anything for money, you might be willing to help me if I told you about Mr. Landry.”

For a full minute, Slack sat silent. Then he gave Doris a bitter smile. “I’ll check out your story, and if you’re handing it to me straight I’ll try to help you work it out so you’ll have enough bread to split from your old man. But if I do, you’ll have to help me.”

Doris leaned forward eagerly. “Oh, I will!” she said. “I will! Tell me how.”

Slack told her.

* * * *

That was Tuesday. On Friday night, Slack made a long-distance telephone call to New Orleans. “Is Mr. Prince there?” he asked the man who answered the phone. Prince was a former client.

When Prince said hello, Slack said, “Hiya, Hon. This is Howard Slack.”

“Slack? The peeper?”

“Right.”

“What do you want?” It was not a cordial greeting.

“I’d like to ask you a couple of questions, Ron. O.K.?”

“It’s your nickel.”

“LSD,” Slack said. “Is there still a market for it? Or did it go down the tube with the hippies?”

“Are you kidding? Listen, I could sell tapioca pudding at ten bucks an ounce if there was a high in it. Sure there’s still a market for LSD. Especially on the Coast. Why? You got some to sell?”

“Well, I could have,” Slack answered cautiously. “Packaged in individual doses, neat and convenient.”

“What do you mean, packaged?”

“Little squares of paper for each dose, bound into pads of a hundred sheets.”

“Neat, all right.” Prince laughed. “That way, we could distribute it through stationery stores and Woolworth’s if we wanted to. How much of it do you have a line on?”

“I’m not sure yet. But a hell of a lot.”

“And you want to know if I’ll take it off your hands, right?”

“Right. And at what price.”

Slack held his breath until Prince replied, “Depends on the quality, quantity, and how greedy you are.”

“The quality’s absolutely first class,” Slack said at once. With Doris Lasswell acting as lookout while Landry was shopping two days before, Slack had let himself into Landry’s trailer with a skeleton key and appropriated one of the pads of paper squares that he had found packed into two large suitcases in Landry’s laboratory closet. Had Landry packed them up that way for shipment or delivery? Slack didn’t know. But he’d tested the stuff himself—eaten one of the squares from his stolen pad—and had been rewarded with a trip so good that he’d never forget it.

Prince was saying, “How do you know the quality’s all that good?”

“I tested it myself, Ron. It’s that good, believe me. Super.”

“Since when are you an acid head?”

“Since never. Except for experiments years ago—and this one test.” He waited. “Ron?”

“Yeah?”

“How much does a dose go for on the street?”

“Since inflation,” Prince said, “about three or four bucks.”

Slack felt a surge of exultation. There were a couple of thousand pads in Landry’s suitcases. With a hundred doses to a pad, at four dollars a dose…

Prince said, “But a buck, a buck and a half, is tops for your cut, Slack. I need something and my distributors need something. We do all the work.”

“Sure,” said Slack, “sure, I understand that.” It was still a lot of money.

“So when do you figure to make delivery?” Prince asked.

“Give me a week, O.K.? I’ll bring it to you myself.”

“O.K., peeper.” Prince hung up.

* * * *

On Sunday night, just as it was getting dark, Doris called Slack at his run-down efficiency apartment on the South Side. She said, “Mr. Slack? He’s going to the movies tonight.”

“Landry?”

“Yes. The nine o’clock show at the Orpheum.”

“How do you know?”

“He told me.”

“How come?”

“After dinner tonight, when my father went off to Casey’s, I looked over and saw Mr. Landry sitting in a chair behind his trailer. He has a little terrace back there, you know? And he looked pretty lonesome. So I took him over a piece of the chocolate cake I made yesterday and hung around while he ate it. He told me he was going to the movies later to see some science-fiction thing at the Orpheum.”

“Did he say the nine o’clock show? You’re sure?”

“Of course I’m sure. You told me to watch him and let you know when you could—”

“Yes, and you’ve done great, Doris. He won’t get out of the theater until after eleven, which gives us plenty of time. So tonight’s the night. As soon as I fill up with gas, I’ll meet you in the A&P parking lot across from your place. O.K.?”

Her voice was shrill with excitement. “It certainly is O.K.! I can hardly wait!”

“About half an hour then,” he said. Then, amused, “You got your trunks all packed to make your getaway from your old man?”

“I’ve had my stuff packed for three days,” Doris replied seriously. “Only it’s not in trunks, just a backpack.” She was silent for a few seconds, then said with fervor before she hung up, “Oh, Mr. Slack, I hope I never see my father again after tonight!”

“You won’t, baby, you won’t,” Slack murmured, staring thoughtfully at the wall. He hadn’t quite decided yet what he’d do about Doris. A teenaged witness with a big mouth wasn’t the safest thing to have running free on your backtrail. But first things first, he thought.

* * * *

The A&P parking area across from Fern wood Mobile Home Park was dark and deserted on Sunday nights. Slack turned off his headlights as he eased into the lot, reversed his car, and pointed it at the exit ramp before he climbed out and acknowledged Doris’s presence. She was seated on the low stone coping that surrounded the lot, her backpack in the shadow at her feet.

She jumped up as he approached her. “Mr. Landry left his house right after I talked to you on the phone,” she told him in a conspiratorial whisper.

“Good,” said Slack. “Now listen, Doris. I’m going into Landry’s to get those suitcases of LSD—it’ll take me two trips they’re so damn heavy, but the whole operation shouldn’t take more than ten or fifteen minutes before we’re on our way to New Orleans. Here.” He handed her his car keys. “Have the car trunk open when I get back with the first load, and put your own stuff in the back seat with my bag. O.K.?”

“O.K. But please hurry!”

Slack crossed the road quietly and disappeared inside the gates of Fernwood Park.

* * * *

Exactly eight minutes later he drove his second-hand Chevrolet out of the A&P lot with two suitcases full of LSD in the trunk and a shivering Doris Lasswell in the passenger seat beside him. “No need to be scared, kid,” he said. “I told you it would be a breeze.”

“I’m not scared,” Doris said. “I’m terribly happy and excited, that’s all. Aren’t you?”

“Yeah, I guess I am at that.” Slack shook his head in disbelief, but his voice held a thread of triumph. “How about us for a couple of operators, Doris? It only takes us a lousy little ten minutes to solve the biggest problems we got. Ten minutes for you to get loose from your old man, ten minutes for me to get rich.” He rolled the word on his tongue in the manner of a man tasting a vintage wine. He drove sedately across town at a speed slightly below the posted limit. The Sunday-night traffic was light. After several miles, he turned onto the interstate highway.