2,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Wildside Press

- Kategorie: Fantasy und Science-Fiction

- Sprache: Englisch

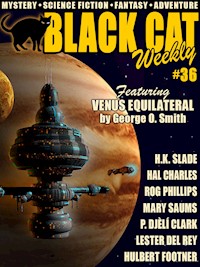

Welcome to Black Cat Weekly #36.

We have another great issue featuring not one, but two full-length books—George O. Smith’s classic collection of linked science fiction stories, Venus Equilateral, and Hulbert Footner’s mystery, Officer!

As always, our acquiring editors have cooked up some delights. From Michael Bracken comes an original police procedural from H.K. Slade, “A Body at the Dam.” Barb Goffman has unearthed “Run Don’t Run,” by Mary Saums, which I know you’ll enjoy. And Cynthia Ward brings us “Shattering the Spear,” by P. Djèlí Clark, a heroic fantasy story—we need more of these in BCW!

Topping things off, we have another solve-it-yourself mystery from Hal Charles, plus classic reprints by Rog Phillips (Vampires!), Lester del Rey (Superstitions in Space!), and Percy James Brebner (Kidnapping! Secret Agents!) All told, lots of terrific reading.

Here’s the lineup:

Mysteries / Suspense / Adventure:

“A Body at the Dam,” by H.K. Slade [Michael Bracken Presents short story]

“A Present from the Past,” by Hal Charles [solve-it-yourself mystery]

“Run Don’t Run,” by Mary Saums [Barb Goffman Presents short story]

“The Missing Signorina,” by Percy James Brebner [short story]

Officer! by Hulbert Footner [novel]

Science Fiction & Fantasy:

“Shattering the Spear,” by P. Djèlí Clark [Cynthia Ward Presents short story]

“Superstition,” by Lester del Rey [short story]

“A Vial of Immortality,” by Rog Phillips [short story]

Venus Equilateral, by George O. Smith [novel]

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 1270

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Ähnliche

Table of Contents

COPYRIGHT INFORMATION

THE CAT’S MEOW

TEAM BLACK CAT

A BODY AT THE DAM, by H.K. Slade

A PRESENT FROM THE PAST, by Hal Charles

RUN DON’T RUN, by Mary Saums

THE MISSING SIGNORINA, by Percy James Brebner

OFFICER! by Hulbert Footner

INTRODUCTION

CHAPTER I

CHAPTER II

CHAPTER III

CHAPTER IV

CHAPTER V

CHAPTER VI

CHAPTER VII

CHAPTER VIII

CHAPTER IX

CHAPTER X

CHAPTER XI

CHAPTER XII

CHAPTER XIII

CHAPTER XIV

CHAPTER XV

CHAPTER XVI

CHAPTER XVII

CHAPTER XVIII

CHAPTER XIX

CHAPTER XX

CHAPTER XXI

SHATTERING THE SPEAR, by P. Djèlí Clark

SUPERSTITION, by Lester del Rey

A VIAL OF IMMORTALITY, by Rog Phillips

VENUS EQUILATERAL, by George O. Smith

INTRODUCTION, by John W. Campbell, Jr.

QRM—INTERPLANETARY

INTERLUDE

CALLING THE EMPRESS

INTERLUDE

RECOIL

INTERLUDE

OFF THE BEAM

INTERLUDE

THE LONG WAY

INTERLUDE

BEAM PIRATE

INTERLUDE

FIRING LINE

INTERLUDE

SPECIAL DELIVERY

INTERLUDE

PANDORA’S MILLIONS

INTERLUDE

MAD HOLIDAY

COPYRIGHT INFORMATION

Copyright © 2022 by Wildside Press LLC.

Published by Wildside Press, LLC.

wildsidepress.com | bcmystery.com

*

“A Body at the Dam” is copyright © 2022 by H.K. Slade. It is an original publication of Black Cat Weekly and appears here for the first time.

“A Present from the Past” is copyright © 2022 by Hal Blythe and Charlie Sweet. Reprinted by permission of the authors.

“The Missing Signorina,” by Percy James Brebner, was originally published in All-Story Weekly, July 27, 1918.

“Run Don’t Run” is copyright © 2010 by Mary Saums. Originally published in Delta Blues. Reprinted by permission of the author.

Officer! by Hulbert Footner originally appeared in 1924.

“Shattering the Spear” is copyright © 2011 by P. Djèlí Clark. It was originally published in Heroic Fantasy Quarterly, January 2011. Reprinted by permission of the author.

“Superstition” is copyright © 1954, renewed 1982 by Lester del Rey. Originally published in Astounding, August 1954. Reprinted by permission of the author’s estate.

“A Vial of Immortality,” by Rog Phillips, was originally published in Amazing Stories, Jan. 1950.

Venus Equilateral, by George O. Smith, is copyright 1942, 1943, 1944, 1945 by Street and Smith for Astounding Science Fiction.

THE CAT’S MEOW

Welcome to Black Cat Weekly #36.

We have another great issue featuring not one, but two full-length books—George O. Smith’s classic collection of linked science fiction stories, Venus Equilateral, and Hulbert Footner’s mystery, Officer!

As always, our acquiring editors have cooked up some delights. From Michael Bracken comes an original police procedural from H.K. Slade, “A Body at the Dam.” Barb Goffman has unearthed “Run Don’t Run,” by Mary Saums, which I know you’ll enjoy. And Cynthia Ward brings us “Shattering the Spear,” by P. Djèlí Clark, a heroic fantasy story—we need more of these in BCW!

Topping things off, we have another solve-it-yourself mystery from Hal Charles, plus classic reprints by Rog Phillips (Vampires!), Lester del Rey (Superstitions in Space!), and Percy James Brebner (Kidnapping! Secret Agents!) All told, lots of terrific reading.

Here’s the lineup:

Mysteries / Suspense / Adventure:

“A Body at the Dam,” by H.K. Slade [Michael Bracken Presents short story]

“A Present from the Past,” by Hal Charles [solve-it-yourself mystery]

“Run Don’t Run,” by Mary Saums [Barb Goffman Presents short story]

“The Missing Signorina,” by Percy James Brebner [short story]

Officer! by Hulbert Footner [novel]

Science Fiction & Fantasy:

“Shattering the Spear,” by P. Djèlí Clark [Cynthia Ward Presents short story]

“Superstition,” by Lester del Rey [short story]

“A Vial of Immortality,” by Rog Phillips [short story]

Venus Equilateral, by George O. Smith [novel]

—John Betancourt

Editor, Black Cat Weekly

TEAM BLACK CAT

EDITOR

John Betancourt

ASSOCIATE EDITORS

Barb Goffman

Michael Bracken

Darrell Schweitzer

Cynthia M. Ward

PRODUCTION

Sam Hogan

Karl Wurf

A BODY AT THE DAM,by H.K. Slade

An unbroken overcast held in the morning’s heat, the charcoal clouds like a weighted blanket. Friday Hampton could smell the coming storm. She rolled up the sleeves on her uniform. By all rights, she should have been wearing the heavy coat tucked away in the trunk of her patrol car, but a winter heat wave had descended on North Carolina the day after Christmas. Now, she had to deal with seventy-degree temperatures in December. The unseasonable weather hadn’t kept the leaves on the oaks and the maples, though. Between the sky, the fallen leaves, and the dead grass, it was a world of muted browns and grays.

“Officer?” a woman shouted from across the empty parking lot. “We’re the ones that called!” The muffled rush of water spilling through the nearby dam all but drowned her out.

The woman had the raw, waxy skin of someone who’d used cheap soap her whole life. She led a small boy, five or six-years-old, by the hand. Iron-on patches covered the holes in the boy’s jeans, but the frays in the denim had been carefully trimmed away so that the patches were hardly noticeable.

There were no cars in the parking lot other than Friday’s cruiser. She thought about the trailer park she’d passed on the way up to Tensdale Dam, the only homes in easy walking distance for a kid that age. She wouldn’t have been surprised if this woman’s single-wide was the nicest in the neighborhood.

“How can I help you, ma’am?” Friday asked once the woman was close enough for conversation. “The call notes I got were a little confusing. You found a suspicious item in the river?”

The woman shook her head. “It won’t me. My boy was playing on them rocks and saw something. Henry, tell the lady officer what you saw.”

The boy hung his head low enough that his long bangs covered his eyes. His mother gave his hand a firm but encouraging tug. “Go on, now,” she ordered, but the boy turned and buried his face in her pantleg.

The woman’s thin lips drew into a grim line, but her eyes went soft and she lovingly patted her son on the head.

Friday knelt down. Already short, the gesture easily brought her to the boy’s eye level. “Henry?” she said and fished in her shirt pocket for the talisman that charmed all children of Henry’s age. “My name’s Officer Hampton. I need some help. Can you help me?”

Reluctantly, still clutching his mother’s leg, the boy rotated to look at Friday.

Friday lacked the high cheekbones and thin eyebrows that turned heads in town, and that never bothered her one bit. What she did have was a smile that put old ladies at ease and got young drunks to do what she asked, which was far more useful in her line of work. She gave one of those smiles to little Henry.

“I know you might be scared, but I think I’ve got a fix for that.” Friday produced a small, metallic sticker from her shirt pocket and made a show of presenting it for the boy to inspect. “This is a badge just like mine. You can’t get one anywhere else except from a police officer. By giving it to you, I’m making you my junior officer. What do you say? Think you’re up for it?”

The boy slowly released his mom’s leg and nodded. Friday extended the badge sticker another inch. After receiving mom’s nod of permission, Henry presented his chest. Friday peeled the sticker and, with great ceremony, placed it on the left side of his chest exactly where she wore her own badge.

Henry beamed. He lifted his chin and the bangs fell away like parting curtains to reveal a set of bright blue eyes. Mom’s lips decompressed and she gave Friday a tight smile equal parts approval and appreciation.

Friday stayed at Henry’s level. “Now that you’re a junior officer, you can’t get in trouble if maybe you went somewhere you weren’t supposed to go or saw something you weren’t supposed to see. Can you help me out and tell me what’s going on?”

“Uhm, I was playing,” Henry began. “I went down the hill a ways and up to the water. There’s, uhm, a trail there? I was walking and playing explorer and there was this space up under the trees. I thought it was a bag of trash, but, uhm, it won’t that. It was a man, and he had blood and stuff on his head.”

Little Henry, with all the earnestness his new position could hope to inspire, pointed to his own temple. “I thought he might could be sleeping, so I poked at him, but he didn’t move. Then I ran back and told momma.”

Patting the boy on the shoulder, Friday rose to her feet. “You did good, Henry. Really good. I’m here now, so I’m going to go see if I can help him. You say he’s down the river?”

“Yes, ma’am,” he said, nodding so hard his chin practically bounced off his chest. “You got to crawl down the rocks and walk a good ways until you see a little crick, then you keep going.”

Henry made an effort to lead the way, but mom put a restraining hand on his collar, and the boy immediately acquiesced.

“I was up here on the walk by the dam, Officer,” the woman said as if admitting to a failing. “I was watching, I swear on a stack of bibles, but the river takes a bend down the way. I couldn’t see him ’til he came running back.”

“I’m sure it’s nothing to worry about, ma’am,” Friday assured her. “Henry did a good job letting you know, though, right?”

“He sure did. He’s a good boy.”

Friday took out a pen and her notepad. “Henry, I’m going to get your mom’s phone number and let you two go on about your day. I’ll call you if I need anything. Don’t go arresting the kids in the neighborhood, though, okay? Wait for backup.”

“Yes, Ms. Officer,” he said and thrust his shoulders so far back that Friday thought his chest might pop out of his shirt.

With mother and son on their way, Friday started the long trek down to the river. The ground beneath her boots was soft, every step embedding more dead grass in the mud.

She keyed up her shoulder mic as she walked. “Charlie Three-Twelve to dispatch.”

Her police radio crackled. “Go ahead, Three-Twelve.”

“Can you get EMS en route to my location? I’m in the park at the base of the Tensdale Dam on the river side. I might have a possible injured subject.”

The ensuing delay in the response was neither a surprise nor a comfort. Everyone was short-staffed these days, even the emergency call center. Friday understood, but no one dangling at the end of a rope liked to be reminded how thin the line was.

“Ten-four, Three-Twelve,” the reply came back. “Be advised that EMS is on diversion due to holiday staffing. Holkum County has the nearest available wagon. ETA of forty-five minutes. We can dispatch Fire until a closer unit frees up?”

Friday thought about how that would go. The week between Christmas and New Year’s was a boom time for first responders. If Fire got called out, the men and women in the fancy raincoats had to bring the whole engine and half a station even if it was for a stubbed toe. Friday didn’t want to be responsible for tying up that many resources for what was most likely just a homeless guy trying to have a peaceful nap out of sight of the public. If it turned out the guy was hurt, two minutes wasn’t going to matter in the grand scheme of things.

“Ten-twenty-two, dispatch. Let me get out there and see what I got before I cause a ruckus.”

Quarried stone lined the steep banks of the Shattuck River beneath the dam, the jagged rocks slick with the morning’s misting. Spindly dead trees littered the rock field, the victims of floods, insects, or the overzealous application of herbicides. Friday maneuvered down the face of the slope, cutting parallel to the waterline and balancing with her hands in hopes of avoiding a spill. That was the last thing she needed. It would take the firefighters half an hour to rescue her and another hour to stop laughing about it.

Little Henry’s path was easy enough to see. Even with the dampness in the air, the narrow strip of muddy riverbank preserved his tiny shoeprints. There were other prints beneath his, more than Friday would have expected to find in such an isolated spot given the holiday and the gloomy weather. They most likely belonged to the homeless man she was going to check on. Friday stepped wide to preserve the shoe impressions out of habit, but the rocks proved treacherous, and she soon conceded the cause.

A hundred yards downriver, the slope gave way to flat woods that ran right to the edge of the Shattuck. A low fog clung to the water, tendrils of white mist spilling over the riverbank and into the woods. It didn’t take long to find the little creek Henry had mentioned, nothing more than a brownish-red trickle of water flowing from the underbrush.

Friday had to duck under a low branch and balance on a deadfall to keep going. Her gear caught on the thorny vines and hampered her progress, but the effort brought her to a little cove tucked out of view from everywhere but the river. Someone had lugged enough rocks from the dam to make a little fire pit, but that had been the extent of their industriousness; they hadn’t packed out a single bit of garbage. Beer cans and food wrappers littered the clearing. A filthy sleeping bag lay stretched out before the soot and charred logs in the firepit. A white plastic grocery bag hung from a branch, limp in the stifling stillness of the day.

There was so much junk, in fact, that at first Friday didn’t see the body.

Her initial thought was that the man in question had just gotten up and walked away, and wouldn’t that make her life easier? A less motivated officer might have turned around and called it a day, but the late Detective Tony Hampton didn’t raise any lazy daughters. Friday made a systematic and thorough search of the cove, just like she’d been trained to do, and found the man tucked among the washed-out root system of an old cottonwood tree.

“Trinton Police,” she announced in her no-nonsense voice, “You all right, sir?”

The man lay as still as anything else on the river. He was turned away from her, lying on his side, arms and legs twined in the roots in a way that could not possibly be comfortable. Friday crept forward and placed a hand on his leg, her gun half out of its holster.

Death. There was no putting into words how it felt, the difference between touching a person and a corpse. The sense came with time. Time and unenviable experience. Some of the old cops, the twenty-year guys, could tell from across a room. Five years into the job, Friday still needed to touch to be sure, but sure she was; the man had no more cares in this world.

White male, hundred and forty pounds, late-thirties at the time of his death. Hands calloused and emaciated, fingernails long and caked with grime. It had been a week since he’d seen a razor, longer than that since he’d had a bath. Exposure, malnutrition, alcoholic hepatitis: any number of things could have killed the man, but Friday would have put her money on the blow that had caved in the side of his skull right at the temple.

“Dispatch, Charlie Three-Twelve. Upgrade my call to a one-oh-three. Go ahead and call out the techs. I’m going to be about a hundred and fifty yards downriver from my patrol car. Have them call me when they get here and I’ll walk them in.”

“Ten-four, Three-Twelve. Be advised, Crime Scene is tied up on that home invasion in the Bellview District. I’ll get them to you when I can get them to you. We’re having to call in a detective to respond. Expect an extended response time.”

“I always do,” Friday said without keying up the mic. She debated about heading back to her patrol car to get crime scene tape, but there was no sense in it. No one was going to stumble across this body without her seeing them.

She studied the wound as much to educate herself as to pass the time. The blood was still wet, so she couldn’t be sure, but it looked like the wound was squared off. She didn’t know how the damp conditions effected coagulation, so she couldn’t even make a guess at the time frame. There were other things she could do, but she’d gotten her hand slapped once for messing with a crime scene. The detectives could be persnickety like that, and she was just a lowly patrol officer. Better to let the detectives handle it. She checked her watch. Almost noon. They might even get there before sunset.

Friday looked around for a place to sit. She was going to be there a while, but every bit of garbage, every muddy shoeprint was potential evidence of a murder. Maybe if she backtracked to the deadfall—

Something wet splattered on the back of Friday’s neck.

“Just perfect,” she said and reached to wipe away what she was fairly certain was bird poop. When she checked, though, it was just water. Rain. Not only was she going to have to stand around for hours guarding a corpse, but she’d have to do it soaked.

That’s when it hit her that the rain would wash away more than her good mood. Even if they left at that very moment, the crime scene techs would arrive to find every bit of evidence washed down the Shattuck.

Concentric ripples appeared on the stretches of river not covered in fog. The storm was coming fast. Friday didn’t even have time to run back to her car for a tarp. In five minutes, the chances of solving this homicide would drop off the edge of a cliff.

* * * *

Rain slapped at the window, and a heavy gust sent the last sweetgum balls of the year skittering across the roof. The racket startled Ambrose Broyhill so badly, he nearly fell out of his recliner. He stroked his upper lip with his knuckles, smoothing his burly mustache and soothing his irritation at having his mid-day nap interrupted.

It’s not like I have anything keeping me from making a second go at it.

He was about to do just that when a pitiful whimper cut through the sounds of the storm. Ambrose hefted his great bulk out of the plush chair, slid his feet into a pair of well-worn slippers, and shuffled down the hall to his bedroom.

Lilo the pit-bull lay curled into a tight ball on top of a comforter that had spilled off the bed. The poor pup was trembling. With a grunt of effort and only a single pop of his left knee, Ambrose lowered himself to the floor and gently patted the dog’s muscled haunch. Lilo raised his massive, blocky head, his eyes turning up to Ambrose.

“It’s okay, boy,” he said. “It’s just a storm. We’re safe in here. You’re always safe with me.”

That was the thing about rescued dogs and old cops; everyone was scared of them, but all they really needed was a little TLC. Gradually, Lilo’s trembling lessened. Bit by bit, the dog scooted closer and closer until he had his big head on Ambrose’s lap. He was almost asleep when the phone rang.

“Hello?” Ambrose said as he stroked Lilo’s ears and whispered calming words to the big dog.

“It’s Friday Hampton, sir,” the voice on the phone said. “I need some help, Detective, and I need it now.”

Ambrose smiled. He had a soft spot for his old partner’s daughter. “That’s retired detective, Friday. Ambrose to you.”

“We can argue etiquette all you want tomorrow, but right now I got a situation and I need a detective.” Her tone brooked no argument. Ambrose sat up a little.

“Tell me what you’ve got.”

Friday’s voice went distant. She must have switched to speaker. She shifted into the near-shout of someone wanting to ensure that they were heard and not interrupted. “I’m out on the Shattuck up by Tensdale Dam. I’ve got a body out in the open, a ton of perishable evidence, and a hell of a storm about to wash over my crime scene like it was biblical times. The cavalry is an hour away. I’m out here by my lonesome until then.”

Ambrose shifted the phone to his other ear and closed his eyes to focus. In spite of his retirement status or perhaps because of it, his pulse quickened as parts of his brain that he’d consigned to storage came online. “Okay. You know how to work the scene. Tell me what you have.”

“I’m in a little clearing. One way in, a two-foot-wide strip of mud on the riverbank. That’s unless you count an amphibious landing, but no sign of a boat pulling up. The decedent looks indigent. Blunt force trauma to the left temple. It’s a weird wound. There’s a square edge to it where the skin broke. Blood’s still wet.”

“Did you take pictures already?”

“No city cell phones for lowly patrol officers. This is my personal phone, and the new IA major made it a firing offense to have pictures of a dead body on a personal phone.”

Not for the first time, Ambrose marveled at how much police work had changed. As dedicated a cop as Friday was, he couldn’t ask her to destroy her career. “Gotcha. Signs of a struggle?”

“He’s covered in dirt, but I can’t tell how much of that is from the attack and how much from the lifestyle. He’s face down, so I can’t see a heck of a lot without moving the body.”

Ambrose nodded his understanding for the benefit of no one. Outside his window, an angry gust drove a sheet of rain against the side of the house. The windchimes on the back patio rang and rattled madly. “I know the protocol,” he said, “but there isn’t time to do things properly. That storm is rolling through here right now, and it’ll obliterate everything when it gets to you. You’re going to be the only one to see the evidence, so let’s get you in there seeing as much as you can.”

Things went quiet on the line as Friday set the phone down to work. Ambrose should have known there would be no hesitation. The girl was squared away.

Her old man would be proud.

“Massive defensive wounds,” she shouted after a few moments. “The left forearm is pulp. No rigor or livor mortis that I can see without cutting all his clothes off. His cell phone’s still in his pocket. So’s his knife and a lighter. Maybe three dollars in change.”

Robbery was unlikely. In Ambrose’s experience, that was hardly ever the motivation when the homeless were involved. Jealousy, sometimes, but most often, it was good old-fashioned anger. “What’s around? Anything unusual?”

“Plenty.” Friday chuckled, the mirthless laugh of someone overwhelmed, on the cusp of giving up. “It’s like a freaking a yard sale out here.”

She’s a good kid, a damned good cop, but this is a no-win scenario and she knows it. She’s out of her depth, but she had the presence of mind to call you, Ambrose.

He put his hand on Lilo’s ribs, felt the dog’s slow, even breath, and let some of that serenity into his voice. “Tell me what you’re looking at, Friday. Systematic and thorough, remember?”

“Okay, okay. There’s a firepit. It’s warm, but not hot. Probably from last night. Junk food wrappers. Chips, cookies, Slim Jims. Things you can shoplift. Some beer cans, a couple of glass bottles. Empty cigarette packs.”

Ambrose could see it in his mind’s eye. Easy enough. It sounded like every homeless camp he’d been to in his thirty years. The solution would be in the details, though. “Tell me about the cans and bottles.”

“The cans are a mixed batch. PBR and Bud. A couple crushed Modelos, but they look old. The bottles…one’s Wild Irish Rose. Mostly empty. Looks like a twenty-two of something…Olde English maybe? Been here long enough to have spiders in it. And a Mike’s Hard Lemonade? A six of them.” There was a thud on the line, probably Friday moving the phone. “One’s in the pack, still cold.”

Interesting. That changes things.

“Look around,” he told her. “See any condoms or drugs or a clean blanket?”

Another pause. Ambrose could hear Friday sifting through junk, bottles clinking together, aluminum cans bouncing off rocks. “Yeah, I found the end to a box of Trojans. It’s wet, but not dirty. Got to be new. How’d you know?”

It was all starting to come into focus. “Who drinks Mike’s Lemonade?”

“Sorority girls?”

Ambrose smiled beneath his mustache, far too seasoned and composed to laugh aloud in such a tense situation. “You think the ladies of Kappa Delta were touring the homeless camps this morning and things got out of hand?”

“Fair point,” Friday acknowledged.

Working down a list that had become almost subliminal after so many murder investigations, Ambrose thought about what he’d want to know if he were assigned to the case.

“Is the weapon there? Maybe a piece of angle iron, or a crowbar? Something heavy with an edge.”

“Nothing,” Friday said quickly, and there was a fresh touch of panic in her voice. “Oh shit. Here comes the rain.”

What are we missing? What do we need?

“Footprints, Friday,” Ambrose urged. “In the mud. Quick, before they wash out.”

Static filled the line, and it took him a moment to realize it wasn’t a dropped call but the roar of heavy rain.

“Mine,” Friday said, now truly shouting. “The boy who found the body. The vic’s work boots. Beneath that…looks like…flat tennis shoes. Vans, maybe?”

Time was running out. Ambrose could hear the downpour picking up. “Don’t worry about that now. Are all the prints coming and going?”

“The boy’s…yeah, going both ways. Spread out where he was running back to mom. The vic’s boots are both ways, too. Bottom layer of the prints, looks like. He must have left before everybody got here. No, there’s one on top of the Vans. Shit. It’s washed out now. I’m sure of it, though. The victim must have left and come back.”

“The Vans, are there any leading back to the park?”

Friday was smart, and if Ambrose’s suspicions were right, that was going to be a problem. If she put the pieces together too quickly, she was going to do something stupid. Sensing his worry, Lilo whined softly.

“It’s coming down in buckets. Everything’s flooding. I can’t…no, the Vans are all heading away from the dam. Shit. Detective, the lake’s pretty much topped off. If they open the spillway—”

Ambrose cut her off. Friday’s thought process was a train barreling towards a washed-out bridge. He had to get ahead of it. “Officer Hampton, listen to me. I want you to get back to your patrol car and wait for back up. Promise me you’ll—”

“I got to go,” she blurted, and the line went dead.

Ambrose stared at his phone, his mouth still open from trying to head off this exact outcome. Lilo lifted his head, his ears pinned back with concern.

“Damn it, boy. She figured it out.”

* * * *

Friday stood on a riverbank that was rapidly becoming indistinguishable from the river itself. The pounding rain drenched her to the skin. She had to hood her eyes with one hand just to keep them open. Her other hand held her SIG 226.

She looked up the creek. Water poured in a torrent from the little ditch, washing loose branches and other debris out into the wide Shattuck River. The footprints were long gone now, but she remembered. They told the story. Fighting against the wind and the suck of the deepening mud on her boots, Friday slogged up the creek into the dense, dark woods.

Maybe she would have gotten there without Detective Broyhill. Maybe she had everything she needed to figure out the murder on her own. Then again, maybe not. The cove had been a perfect out-of-the-way place. Hardly anyone ever came up to the dam at this time of the year. It was too ugly, too drab. Spring was a different story, but in winter, the only reason to come there was to get away from something.

A homeless man wanting a quiet spot to build a fire and hide from the scrutiny of polite society? All he’d need would be a few beers and some non-perishable food, and the cove provided everything else. A pair of teenage lovers, off from school and looking for a spot to slip away from the folk’s trailer for a frantic bit of affection? Well, the cove would work just fine for that, too.

The problem only came when the two mixed.

The creek was a straight shot, no curves or bends. Probably engineered that way. Friday’s shorter stature became an asset as she ducked under fallen logs and overgrown bushes. She spared a thought to hope the warmer weather hadn’t thrown nature’s cycle off enough that she had to worry about snakes. The creek was the perfect environment for water moccasins, and she already had enough on her plate.

As Friday moved deeper into the woods, the trees transitioned from broadleaf to conifer. The dense pine needle canopy cut the force of the storm considerably, but it also blocked what little daylight there was and left the forest floor in near darkness. Friday had a flashlight that she knew from experience would work even underwater, but the light would give her away to anyone hiding in woods.

There were no good choices. See where she was going or be seen coming from where she was? Having already thrown caution to the wind, Friday elected for stealth over safety. At least she had the advantage of knowing where her quarry was heading.

The creek led back to a steel culvert that ran under a fence separating the woods from the nearby trailer park. Friday had once recovered a stolen dirt bike from there, and she knew it would be choked with leaves and garbage, at least until the storm cleaned it out. Anyone running from the river would have to go around or shelter on this side of the fence. She was counting on the latter. It was the only way she was going to catch the murderer.

Up to her knees in water, Friday found the most likely path out of the creek. She holstered her weapon and, grabbing roots and rocks for leverage, scrambled up the bank to the relatively dry pine needle carpet of the forest floor.

She spit rainwater from her mouth and keyed up her shoulder mic. “Dispatch, this is Three-Twelve. I’ve got a location change.”

“Go ahead with your nature change, Three-Twelve.”

“I’m back in the woods west of the Shattuck. Can you have responding units head to the trailer park off the access road? Go ahead and detain anyone out in this weather, especially teenagers.”

“Copy, Three-Twelve. Nearest unit shows an ETA of eighteen minutes. Do you need me to expedite?”

A young man emerged from the lee of a thick stand of firs only a stride or two away. He stood a foot taller than Friday, all sinew and muscle, and held a 2x2 length of lumber like a war club. Behind him, a teenage girl peeked out from the trees. The rain had plastered her bleached hair against her face, and her makeup ran down her cheeks and left her looking like a drowned racoon.

“Yeah, dispatch,” Friday said with overexaggerated calm, “go ahead and expedite.”

The boy hefted the board and took a step forward. He shivered. His eyes, red nearly to the point of glowing, were nonetheless resolute.

Friday’s gun came out in a blur. “Slow your roll,” she commanded. The mousy girl shrieked, clutching her sodden T-shirt. The boy stopped.

The board in the boy’s hands beaded water like pressure-treated lumber. It had a fresh cut to one end, a sharp edge that might still have a bit of blood and skin in the grain. Friday couldn’t be sure without a closer examination.

Friday played the hand she’d been dealt. She did not want to shoot this kid, but neither did she want to end up another body on the banks of the Shattuck.

“This doesn’t have to go like you’re thinking it has to go,” she said, her gun never wavering. “I think I know what happened. I can help you.”

“You don’t know shit,” the boy said and bounced the board on his palm. Friday could see him building up enough courage to charge. It was bad. He wasn’t just violent, he was stupid.

“You just went down to the river to get some time with your girlfriend, right?” Friday suggested. “Some peace and quiet away from all the little brothers and sisters running around the trailer? Nothing wrong with that. Hell, I’m not the make-out police. But then some crazy old drunk stumbled up on you two. Probably scared the hell out of you right?”

“I ain’t scared of nothing,”

Friday extended her non-dominant hand, palm opening in a calming gesture. “Now’s your chance to show everyone how smart you are. Set the board in the dirt, and the three of us are going to walk out of here together. We’ll get us some dry clothes and you can tell me all about what happened over a Big Mac. Or not. Maybe you want to talk to your free lawyer and let them sort it out for you. That’s what I’d do, but it’s your choice. If you take another step, though, you don’t get any more choices.”

He thought about it, chewed on the decision like a pip. The kid was skinny enough that Friday saw the ripple of tension in his arm muscles as he made his choice. The wrong choice.

“Gavin!” the mousy girl shrieked.

It was enough to snap the kid out of it. His narrow eyes relaxed, then drooped. Similarly, the tension drained from his arms, first from his shoulders, then his forearms, then his hands. The board dropped from his limp fingers, falling to the ground next to his muddy Vans.

* * * *

Ambrose paced his bedroom, holding his phone away from his ear so that he could yell into it more effectively.

“Bullshit, Barb,” he thundered along with the storm. “I don’t care how short-staffed you are. You’ve got an officer alone in the woods with a murderer. You’re the watch commander. Find a way to get someone there ten minutes ago!”

Lilo, who never barked, growled low and menacingly, adding his voice to the argument in the only way he knew how. Ambrose gave the big dog a pat, grateful for the show of solidarity.

“I hear you, Detective,” the young captain protested, “but I’ve got people on the way. I don’t know what else you want me to do.”

Ambrose bit his knuckle, fully aware that he could only push so far. He’d known now-Captain Barbara Rice when she was a recruit, been her training officer at one point, but there was a limit to her indulgence, and he was right up against it. Still, if the choice was between burning bridges and wondering if he could have done more to save his old partner’s daughter, there really wasn’t a choice.

“Listen,” he started, but his phone beeped with an incoming text message. He let Barb go so he could check it.

Ambrose’s stomach finally stopped percolating. It was from Friday.

“Two in custody. Tell you about it over coffee soon. Thanks for the help detective.”

Lilo sat at his feet, his giant head cocked to one side. Ambrose put the phone down on the dresser. His knees gave out and he dropped his substantial backside on the end of the bed so hard that he bounced slightly.

“See, boy? Nothing to worry about.”

They both ignored the wetness on his cheeks.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

H.K. Slade is a writer specializing in police procedurals set in eastern North Carolina. You can find some of his previously published works in Mystery Weekly, Everyday Fiction, The Yard, and Black Cat Mystery Magazine as well as on his own website: hkslade.com.

A PRESENT FROM THE PAST,by Hal Charles

No matter her age, Cass always loved her grandmother and grandfather’s creative birthday parties. Today, as Cass stepped into the front room of their rustic farmhouse, she felt she had passed through a time portal. The room was filled with the sweet smell of incense along with the unmistakable notes from a sitar.

Cass’ grandparents were a little different from those of her friends. While both of them held advanced degrees—her granddad in English, her grandmother in physics—they had chosen a hippie, back-to-nature lifestyle. Her earliest memories of the farm were of listening to British Invasion records and learning to tie-dye t-shirts.

And, of course, there were the stories. Her grandmother’s face always lit up when she showed the pictures of her and “the girls” screaming their heads off at the famous Beatles performance at Shea Stadium in 1965 while her granddad’s favorite tales involved their epic journey to Woodstock in the psychedelic VW that still sat in the barn out back.

Cass waded through the crowd of total strangers engaged in animated conversations. Over the years, her grandparents had entertained themselves—and her—with games designed to “exercise” her mind.

“Finally,” said her grandmother, emerging from the strangers, “the birthday girl has arrived.”

“Grandmother,” said Cass, “what’s going on?”

The older woman smiled. “Granddad will get home a little later, but I thought we’d better get started.”

“Started with what?” Cass said, tilting her head.

“The game, of course.”

“Who are all these people?” said Cass.

“Oh, they’re part of the game. In the next few minutes you’ll meet several people. Your mission, should you choose to accept it,” said her grandmother with a titter, “is to determine what they have in common.”

Suddenly, a tall woman with exceedingly short hair approached them seemingly in a hurry. “Martha,” she said to Cass’ grandmother, “I promised John I’d be back home as soon as I got him everything he needed from the grocery.”

“Cass, darling,” said Martha, “this is Sally Jenkins from my book club, and—”

“I’d like to have some fun tonight,” interrupted Sally, “but I have to head out.” With that, she disappeared into the swirl of people.

“That was quick,” said Cass as she noticed a heavyset man moving in their direction.

Catching her granddaughter’s eye, Martha said, “Let me introduce Maxwell Carrington. He’s in line to start construction on the new civic center downtown.”

“You can call me Max,” said the mustached man. “I’m afraid we have a few more details to hammer out before any building can begin.”

“He’s just being modest,” said Martha, grabbing the hand of a bright-eyed young woman to their right. “Lucy, I’d like you to meet my granddaughter, Cass.”

Cass nodded.

“Lucy just opened the new jewelry store over on Collins Street.”

When the young woman noticed Cass admiring the rings she wore, she said, “You know what they say about diamonds being a girl’s best friend.”

Cass’ mind was spinning as she tried to find some pattern that would pull these people together. Perhaps the common factor was their newness to town or that they were all in business.

Before she could say anything, a serious looking woman in a dark uniform appeared.

“Rita Thompson,” said Martha, “you must have come straight from work.”

The woman nodded.

“Rita works with the transit authority,” said Martha.

“Sorry I’m a little late,” said the woman. “Some joker mowed down half a block of parking meters on Main. Been working those streets for ten years and never saw such a mess.”

Well, thought Cass, there went her first two possible solutions. Even with all the noise, she had to focus.

Just then she spotted a frail woman sitting by herself toward the back of the room. “Who’s that?”

Martha’s face grew dour. “That’s Eleanor. She volunteers at our church. Pretty lonely lady, I’m afraid.”

Hearing her last words, Cass smiled. “Grandmother, you better put on Shirley Ellis’ ’Name Game’ because I’ve got this puzzle figured out.”

Solution

When her grandmother described Eleanor as a lonely person working at church, everything came together: a long, tall Sally wanting to have some fun; Maxwell hammering out details; bright-eyed Lucy with diamonds; and Rita patrolling the parking meters. They all had first names from Beatles songs. When Cass’ granddad arrived, he brought her birthday present: a box set of the Fab Four’s greatest hits.

RUN DON’T RUN,by Mary Saums

The Barb Goffman Presents series showcasesthe best in modern mystery and crime stories,

personally selected by one of the most acclaimedshort stories authors and editors in the mysteryfield, Barb Goffman, for Black Cat Weekly.

The replay’s always the same. An old man, skinny dude, hugs the corner of a building ahead. He steps from darkness into the low light of a closed store’s window. He carries a brown bag. His tweed hat and suit jacket shine from wear. His stiff shuffle does not hurry, does not lag.

His eyes lie. They’re good at it. At his age, it comes natural. They stare straight ahead, do not blink. They pretend not to see me, that everything is fine, that there’s no hurry, that he sees nothing. I understood this part but not the whole lie, hidden well by a master but so obvious to me now.

Traffic stills in my memory as his soft footsteps fade in the distance behind me. A long beat of thicker quiet hangs in the night, a hesitation, just before a click, ahead and to my left. I see an arm in slow motion coming out straight from behind a car, swiveling to point and squeeze, the barrel flash, the hit like a grizzly knocking me down and sitting on my chest, suffocating, pressing me into the asphalt like it was water, great claws ripping into my heart, drowning me, pushing a lost memory to the surface. Then cold, then darkness. I thought I was gone.

I came back gradually to lights and sounds. Not the light of heaven or songs of angels welcoming me to my reward. Painful fluorescents overhead stung my eyes. Sirens and ambulance shrieks. Yelling, car horns, garbage trucks. Chicago.

Louder and closer was the fool yammering of my partner, Detective George Ehrman, talking about the good food in the cafeteria, for Christ sakes, about how he’d been at the hospital every minute he wasn’t on duty. At this, my eyes adjusted enough to see that the nurse standing on the other side of my bed was white. She came into focus as she leaned closer. Young and pretty. Her expression, eyes widening, lips tightening with patience, confirmed what George said, that he’d been a constant annoyance.

My mouth must have twitched. She smiled back at me and said, “You’re at Saint Joseph, Mr. Crosby. You’re going to be fine. Rest.”

Even then, as early as that, the plan was in my head. Every word George spoke, going on about how lucky I was, how the bullet grazed a rib, nothing else, about the time he got shot and his life passed before his eyes. All of it made things clearer, more sure in my mind.

“Like a reel of film,” he said. “Everybody I ever knew, special days, days when nothing happened, all three-D and in color, the whole thing. You know the weird part? This feeling, like God was telling me everything was all right. No fire and brimstone over not going to confession. I’d had a good life. No regrets. I was ready to go. Anything like that happen to you?”

I managed to croak out a few words. “No, man. Nothing like that.”

He talked nonstop. I pushed my thoughts away for later. I persuaded him to go home, that I was fine.

The hospital noises in the hall became more familiar and more hushed. I slept hard and woke up in the dark. The nurse came in to change the IV bag. Then I was left alone in the quiet to consider.

When I’d thought I was about to die, there’d been no movie. No feeling that it was all good, that I could go into the great beyond happy. George said he’d had no regrets. Regrets were about all I had. They hit me as I lay in that hospital bed like a second bullet. The force slapped my insides awake, like my soul had been in hibernation. I saw the whole of my life in one strange scene from thirteen years earlier.

I was eighteen, just out of high school, with a bus ticket out of Mississippi in my pocket. I had cousins living in Chicago who said they could get me a job and I could stay with them until I was on my feet. I told my father the night before I was going to leave. He didn’t have much to say.

The next morning before I went to the station, I walked down to the riverbank to tell him goodbye. He hung out there every day with a bunch of other old sots who pretended to fish. I stood next to him a while, neither of us saying anything, just watching the corks bob in the water, before he told his buddies.

“My boy here is leaving.” He put his hand on my shoulder. A couple of the fishermen turned and said, “That right?” and “Whereabouts you going?”

I said, “Chicago,” and while some made friendly comments, one old man turned toward me in his ratty lawn chair and fixed me with a hard stare.

“Lots of dust up there. Lots of wind. And a whole lotta concrete.” He moved his fishing pole to his left hand and reached down with his right. His fingers dug into the ground and came up with a ball of red-and-black soil. “It’s a cold, cold place.” He looked up and held his hand out toward me. “This is who you are, young son. Don’t forget.”

Crazy old drunk, I thought. And I did forget. The city’s excitement pulled me in from the first minute I stepped off the bus.

Five years later, I was a rookie in the police department. Got married but it didn’t last. I loved my job. Thought it would be enough. It wasn’t. Earlier brushes with death in the line of duty had not deterred me. This time, I realized I was not immortal. Even my love of the city was about gone. As I lay in the hospital, that bony fist of dirt, the pungent smell of fish and the river and the past kept rising up before me.

The day I was released from the hospital, George waited outside the exit doors when the attendant rolled my wheelchair to the curb. A good breeze from the lake pushed us along to his car. Jackhammers in the parking lot make it hard to hear each other. We drove past a construction site where the high keen of cutting metal sliced through the air. I looked up to rusted trestles. The el screeched by me one last time.

* * * *

A different metal-on-metal scratching twanged in the breeze and blew into my car on the way to the river. It was the healing kind, a sweet sound that made me grin as I drove through the countryside. It moved and slid around, sorrowful and jubilant, went through my chest and wrapped around me like it was part of the sunlight, or maybe the midday heat was making it wave up out of the fields before it floated down and out over the Pearl River.

I’d settled into small-town life again. I took a sandwich every day for lunch and drove out to a picnic spot past Jester Dupree’s land, hearing him playing slide on one of his guitars he’d made from scraps. Neither he nor his house could be seen from the main road. It made no difference. His improvisations carried for miles here, where the terrain was flat. The locals could picture him easily. Didn’t need to see him to know he was sitting under his tree. Didn’t need to see his big hands, gnarled from old age and six or seven decades of farm work, somehow became young again when he played.

This particular day, six years after I left Chicago, he wasn’t in top form. He kept starting and stopping and missing notes. The tunes sounded like he was aggravated with himself or that his mind was on something else. Didn’t matter to me. His playing eased the job I had to do. After I had my lunch, I’d be on my way down the road to serve a warrant.

I’d joined the sheriff’s department when I came back to Mississippi, still in Allmon County, where I was raised. Now I lived in Solley, the county seat. A few years after I moved home, when the old sheriff died, I filled in and then got the job in the next election.

When the music stopped, I sat a little longer at the picnic table in the shade. Then I gathered my trash, got into the patrol car, and drove east about a mile to a rental house on the water.

I wasn’t looking forward to confronting the man I came to see. As much as I hated the thought, Terrell Long was probably here in Mississippi because of me.

I knew Terrell in Chicago. Not friends. I busted him for peddling dope a dozen or more times from a juvie on up. He was the kind of kid who lied every time he opened his mouth. Was known to cheat people who helped him. Fought and argued for no reason.

In spite of these things, Terrell had a certain charm that made me want to believe he had potential. He was still a screwup, still had a mean streak when he got drunk, but he was one who might make something of himself one day, legally, if he could just get his shit together and grow up.

I hadn’t given him a thought in years when he showed up a few days earlier in Solley at my office. There he was, in the middle of August, wearing a yellow polyester shirt and yellow plaid pants and sweating like a hog. I watched him through the window, stretching out of the car, looking as out of place as an alien from Mars. He appraised the surrounding buildings with a disapproving eye before doing a city strut down the sidewalk and into the building.

He leaned into the frame of my office door, fanned himself with a thin-brimmed summer hat, smiling like he’d hit the lottery.

“Well, well. Sheriff. How ’bout that.” He was a man now, probably twenty-seven if I figured right, but still looked like an undernourished kid.

“Terrell. You’re a long way from home.”

“On vacation. Actually, I’m on my way to New Orleans. Got a new place down there. Thought I’d take a side trip to see your domain.” He looked around the walls, nodding. “Nice. Looks like you’re staying. Hard to believe.”

“How did you know I was here?”

“Oh, you know me. I always keep up with people.”

We walked outside together. He wiped a handkerchief across his brow and put his hat on. He said he had gone straight. I didn’t ask for specifics. I tried to ignore the hint of worry in the back of my mind. I wished him luck.

When I saw him walking downtown two days later, I knew he hadn’t changed. Can’t say I was altogether surprised. He said he liked it here, enough to maybe buy a place nearby. Said he decided to stay in town a while to check things out.

The next day, I got a phone call from my ex-partner, George, in Chicago.

“Let me guess,” I said before he told me his reason for calling. “Terrell Long is in trouble, and you think he might be headed my way.”

A pause. “You’ve seen him.”

“Yep.”

“It’s worse than that. He’s playing Little Eddie.”

I spun my chair around, put my legs up on the desk, leaned back, and rubbed my eyes. Little Eddie Burton, son of Big Eddie and heir to his drug numbers and prostitution empire, got his MBA and joined the family business, one that grew considerably as Little Eddie was given more control. This wasn’t totally due to his business skills. He showed early talent in areas usually reserved for the old man’s lieutenants. He got a quick reputation for being as ruthless and intimidating as the best of them. He was linked to a dozen or more murders in the Chicago area. We never got a conviction on him. Too slick.

I had a hard time believing George. “How is this possible? Terrell’s never been anything but small-time.”

“All I know for sure,” George said, “is Little Eddie’s pissed enough to come for Terrell himself. The word inside is that he and two of his goons left this morning. They know he’s there. So be careful, my friend.”

“Yeah. Thanks, George.”

After I hung up, I wished I had asked how they knew he was in town. Had Terrell called Little Eddie from here? More likely, Terrell got drunk and talked too much, as usual, about his plans before he left.

I tried to warn him. I drove on out to the rental house where he was staying. He wasn’t there. I went back after work, and again around nine that night. I stopped in at the local clubs and asked around.

When he wasn’t at Brace’s, the last one, I thought, hoped, he’d left town already. He might be in New Orleans by now. With any luck, Little Eddie and his boys had skipped on out of Solley altogether. I sat at the bar and ordered a beer.

“That’s right. Sit down and relax,” Charlie Brace said. “They’re gonna start the next set in a minute.” Charlie always hired good musicians on the weekends. He used to be a bandleader himself in the old days, booking gigs and playing bass in jazz and blues bands around the South. He sure had some stories.

He told me a little about the band there that night, pointed to the stage and said, “You see the drummer? His great-granddaddy gave me my first job. He was a strange bird. Always had the best working for him though. Said he never hired a man just because he was a good player, but he had to walk right too. Wouldn’t decide on him until after the audition and had time to watch him walk away. It’s true. I saw him do it many a time.”

“You mean, like, to see if they were drunks?”

Charlie shook his head. “I don’t think so. He never would say what he was looking for. Just said he could see who they were. He was a smart guy. Had big crowds everywhere we went. Smart, but a little strange. Eccentric, I guess you’d say.”

I stayed until the band finished their last number. Early next morning, I had a meeting at the courthouse and didn’t get back to my office until about ten o’clock. A woman was inside waiting on me. She had a black eye and bruises on her arms. She filed a report claiming Terrell Long was the man who hit her. I made a few calls before getting the warrant, but I believed her. This was the business I dreaded, what brought me out past Jester’s land that day, to bring Terrell to jail.

This time, his car was there. I glanced inside it, saw nothing unusual, on the way to the porch. The screen door was closed, but the wooden one stood open. Through the screen, I saw an overturned chair in the front room.

I knocked and called his name. Nothing. I stepped inside, saw a broken vase on the floor, walked through, checking rooms, all trashed. In the kitchen, some red splatters, surely blood, dotted the sink and counter.

I went out the back door, circled, and returned to his car. That’s when I noticed the tracks of a heavier, wider vehicle. It had pulled in and backed out after Terrell came home. From over the fields, I heard Jester’s guitar again, the tune moving in a disjointed, raggedy way, like he was distracted again.

Or somebody was with him.

Jester had seen a lot in his years, but he was still a shy man. People made him nervous. He could play at Brace’s with the other old-timers, but that was because he got lost in their company and what they played. One-on-one, he messed up.

I ran to my vehicle and got the dispatcher on the line as I drove. A few minutes later, I turned onto the dirt drive to Jester’s secluded house. I passed a windbreak of a double row of pines set into an upward slope. Just beyond that, his house came into view. My heart sank upon seeing a new four-wheel-drive SUV, parked in the grass and pointed outward toward the main road, as if for a quick getaway.

The one-story farmhouse had a tin roof and wide front porch. Makeshift tables scattered around the side yard held all sorts of machine parts with lawn mowers and other household appliances in various states of repair. Behind them, the barn and sheds looked as weathered as if they’d stood there a hundred years.

Jester looked about that old himself. He wore overalls and a T-shirt like he always did. He sat in a cane-back chair in his usual spot, in the front yard under an oak that gave a wide ring of shade. Next to him, he’d set up a table full of small tools, wire, and bits of metal. A bucket of ice, a spit can, and a smooth-coated mutt sat nearby on the ground. A primitive replica of a National guitar leaned against the table.

It was a work of art. Not just the homemade guitar, the whole picture. The lines of history in Jester’s face alone told their own story. The surroundings told another, of contrasts between the peace of an old man and his home and the threat leaning toward him, Little Eddie, smiling, all innocence. I watched him as I approached, watched him rest the wire cutters he held down on the table and then turn his palms upward as if he had nothing to hide.

“Afternoon, Sheriff,” Jester said.

I crossed to him, shook his hand. Little Eddie either didn’t recognize me or pretended he didn’t. His smile dimmed a fraction when I held my hand out to him as well, but he took it. Two broad-backed henchmen walked toward us from the side yard. They looked like feds out of their element, wearing jackets on a hot day out in the sticks of Mississippi. After a look from their boss, they smiled like gargoyles and stepped farther away from the shorter, slimmer guy with a bloodied lip who walked between them. Terrell.

“Sorry to interrupt while you have company,” I said.

“They’re not company,” Jester said. “Strangers. Real-estate people.”

Little Eddie and his gargoyles grinned wider.

“I didn’t realize you were thinking about selling,” I said.

“I’m not,” Jester said. “They just think they can outfox an old man and take his land for nothing like I ain’t got any sense.”

“Whoa, now, Mr. Dupree,” Little Eddie said. “That is not the case. I’m here to do the opposite. I like your place for myself, not for resale or making money off you. I got plenty of money. What I want is for you to afford to live wherever you want in luxury. An old brother such as yourself deserves that after all you’ve been through. Think about it. If you could live anywhere, anywhere at all, where would you go?”

Jester looked up into the oak branches. “I used to want to live in the mountains. There was a TV show about Colorado. I went out there. It was beautiful, in its own way. I rode all over. But it was empty. Like a shell. Pretty colors. No soul. My place suits me better. Good fishing right here. Ain’t that right, Sheriff?” He picked up his guitar again and started plinking around.

“Pretty good,” I said.