Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Atlantic Books

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

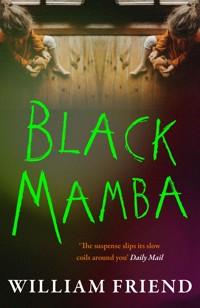

'Great fun... the suspense slips its slow coils around you' Daily Mail Daddy, there's a man in our room... This is the chilling announcement Alfie hears one night, when he wakes in his quiet, suburban house to find his twin daughters at the foot of his bed. It's been nine months since Pippa - their mother - suddenly died and they've been unsettled ever since, so Alfie assumes they've probably had a nightmare. Still, he goes to check to reassure the girls. As expected he finds no man, but in the following days the girls begin to refer to someone called Black Mamba. What seemingly begins as an imaginary friend quickly develops into something darker, more obsessive, potentially violent. Alfie finds himself struggling to cope, and so he turns to Julia - Pippa's twin and a psychotherapist - for help. But as Black Mamba's coils tighten around the girls, Alfie and Julia must contend with their own unspoken sense of loss, their unacknowledged attraction to one another, and the true character of the presence poisoning the twins' minds... A darkling tale of tragedy, hauntings and sexual desire, Black Mamba is a novel of a father's love for his struggling daughters, and a widower's growing love for a woman after his wife's death. With smart, gothicky touches and a large and generous challenge to our assumptions of what and who constitutes a modern family, it explores both the limits we'll go to for our children and the sunken taboos of grief - of how erotics can still exist, and can even be life giving, after suffering loss.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 357

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

First published in hardback in Great Britain in 2022 by

Atlantic Books, an imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd.

Copyright © William Friend, 2022

The moral right of William Friend to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities, is entirely coincidental.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Hardback ISBN: 978 1 83895 655 4

Trade paperback ISBN: 978 1 83895 656 1

EBook ISBN: 978 1 83895 657 8

Printed in Great Britain

Atlantic Books

An Imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd

Ormond House

26–27 Boswell Street

London

WC1N 3JZ

www.atlantic-books.co.uk

For my parents.

One

Alfie

This morning, I heard the name Black Mamba for the first time, and it made me remember some dreams. Not mine; dreams that my daughters had. Visions that splintered their sleep.

It began nine months after the accident. Every night, during the devil’s hour, I’d wake to find the twins standing motionless at the foot of my bed, their faces veiled by the dark.

Daddy, there’s a man in our room.

Those words became familiar, like a choral refrain, and could stir my body whilst my mind, or the better part of it, remained asleep. I’d shift beneath the cold, stiff sheets, flatten my nose against the pillow and sigh. No there isn’t, I’d say. But my arm, half dead with sleep, would lift the duvet all the same and let the girls clamber in, to nestle in the cleft where their mum had once slept.

Naturally, the first night was different. On the first night, the twins’ mere presence at my bedside, sudden and unexpected, sent a shot of adrenaline through me.

‘Daddy, there’s a man in our room.’

The sentence jerked me upright, like the tug of a noose and the floor falling through beneath my feet.

‘A man?’ I said.

‘A man.’

And the girls stood so still, and their voices were so flat and toneless and dead that I could scarcely breathe; yet somehow I gathered the strength to tiptoe out of my room and towards theirs.

‘Stay here,’ I whispered, but they wouldn’t let me leave them, so we shuffled together down the staircase, their tiny hands squeezing mine as we listened. And it was only the silence – the pure, solid hush of night – that began, finally, to calm me. Blood flowed back to my face and neck, and I started to feel like an adult again. Like a father.

‘Are you sure you weren’t dreaming?’

‘It wasn’t a dream. It was real. He was there.’

Into their room we went, and the snap of the electric light instantly illuminated everything, revealing nothing, no one. I flung open the wardrobe doors; lifted the duvet, with its chalk-blue swirls, to search beneath their bed. Unvacuumed carpet and misplaced toys – but no one there.

‘What did he look like?’

‘He . . . he . . .’ Their voices quivered, as feeling returned, and they fumbled for their words. ‘It was dark. We couldn’t see.’

Down another flight, to the ground floor, where we flooded each room with reassuring light. We checked everything: windows, doors, locks. Nothing was open, nothing was smashed. Bewildered, the girls turned to each other, half in search of support, half in suspicion. We retraced our steps.

‘Where did you see him?’ I asked. ‘Show me.’ And, just like that, all synchrony in their words and movements fell apart.

‘He was out here,’ Sylvie said, her finger charting vaguely across the landing. ‘We saw him through the doorway.’

But Cassia jerked her head and cried, ‘No, no, he came into our room!’

‘But the door was closed.’

‘Exactly.’

And suddenly they both seemed very tired. I stroked and kissed their heads; strands of their static blonde hair gleamed in the low light.

‘It must have been a dream,’ I said.

‘It wasn’t a dream.’

‘Let’s get you back to bed.’

‘Why can’t we sleep with you?’

The girls’ night visits persisted for several weeks, and I dozed through each one more deeply than the last, until the visits themselves took on a dreamlike quality; until sometimes it was only the girls’ presence the next morning – their tiny bodies curled up next to mine – that reminded me of their appearance in the night, and of what they’d said.

Then the visits stopped, just as they’d begun: suddenly and without explanation. I woke each morning to an empty bed, and the memory of the whole thing started to fade. I never asked the girls if the nightmares had ceased. They must have, or else why had the visits? Nor did I question why they’d begun in the first place, nine long months after the accident. I pushed those thoughts to the back of my mind – assuming it had all meant nothing; assuming it had run its course.

It was only this morning, when Marian came round with jam tarts and tears, and the girls told me about Black Mamba, that I remembered, in a rush, those moonlit serenades from a month ago – the girls’ dead eyes and voices, and the things they’d said, echoing in my head like a leitmotif; strings that keen and tremble long after being touched.

Julia

I’ve come to the house – not because I want to, but because he’s asked me to.

Hart House, No. 4, Allington Square, London: the house where I grew up. I loved it once, as we all did, and part of me still does. My happiest memories are connected to this house, as well as the most frightening, which makes for what people in my profession call a ‘compound emotional response’. In every room, the walls are pale and blank, but they bear, in my mind’s eye, the imprint of a thousand smiles; a palimpsest of all the birthdays I’ve celebrated within them – nearly 100, for no fewer than seven people.

Two of those people are dead now. I see them in the walls here too.

Alfie opens the front door with a soft smile.

Pretty, in a manly sort of way. That’s what I thought of him when we first met, almost a decade ago. Now he’s pretty but damaged, his face lined, his sandy hair mazy and thick. He looks more grizzled than he used to, though not as a result of maturity, but of trauma. I’m not judging. I look dreadful too, or at least assume that I do. I haven’t looked in a mirror properly since the accident.

‘Thanks for coming,’ he says, taking my coat. Still a gentleman, I think, even after all that’s happened.

No – more so, I realise, sadly. He was never like this when Pippa was alive. I’d come to visit, and Alfie wouldn’t so much as look up from the telly. He’d just call out, cheerily, from where he lay on the sofa, one twin tucked beneath each brawny arm, and jut out his cheek for me to kiss. Now I watch him fold my scarf before draping it carefully over the bannister, and his tenderness is hard to bear. We move into the kitchen, and I distract myself by looking at the girls’ latest drawings, pinned to the fridge by magnets.

‘They’re in bed,’ I hear him say. I nod without turning. Sylvie has drawn a whirl of falling petals, with hard black outlines and softly smudged interiors. Cassia has drawn blue crystals, cold and clear. The girls’ names, in the far corners, are calligraphed with letters that put my own crabbed scrawl to shame. I brush my hand reverently across the paper.

It’s dark outside, and cold in the kitchen. I hear the clink of mugs, the flick of the kettle. Alfie’s brewing tea. Normally when we’re together, we drink – really drink – but not tonight. Today is the first of the month, just like the day of the accident. Wine would feel inappropriate, as it often does when you need it most.

I assume he needs it. Maybe that’s just projection. I should try to find out.

‘How are you?’ I ask, keeping my back turned.

‘Fine,’ he answers, speaking into the sink. His voice is flat, unreadable, but I don’t argue. For all I know it might be true, on most days at least. I’m fine most days too. The anguish has finally eased. I know, instinctively, that he’s at his worst when he’s around me, just as I’m at my worst when he invites me to Hart House.

He pours some tea into my favourite mug, black and speckled with stars, and we sit at the table. The stars appear only when the mug is hot; by the time around half have been snuffed out, it’s safe to drink.

‘How are you?’ he parries, eventually, fiddling with the handle of his own mug, which looks tiny next to the span of his palm and fingers. Alfie’s a big man; a smart one, too, and softly spoken.

‘I’m fine, too, I guess. Keeping busy.’

He nods, tightly. There’s something on his mind, something he wants to tell me. This wasn’t a routine invitation; I thought that on the phone this afternoon. Something about his voice – breathless, catching – struck me as off.

‘At the clinic?’

‘Mm,’ I say. ‘Finally seeing a full roster again. More or less.’

After the accident, I couldn’t work for months. I took long-term sick leave, which only made things worse. I needed to work and I needed therapy, but – given my day job – both options felt closed to me. Like a cold, there was no cure; I just had to wait it out. Things are better now, at least a bit. I can work through my pain. I can talk about it. Other people can give me theirs again.

I sip some tea to mask the awkward silence, and burn my tongue. The stars are still shining furiously. I only have myself to blame.

‘Have they called you again?’ I ask. ‘KCL, I mean. About going back.’ Alfie’s worked at universities for as long as I’ve known him.

‘No, no,’ he says quickly. ‘There’s no pressure. Not this year.’ Whatever’s bothering him, then, it isn’t that.

I push my mug to one side, and do what I do with all recalcitrant clients: fight the urge to fill the awkward gaps; use the silence against them.

Eventually, he cracks. ‘Marian was here this morning,’ he says tentatively, and at last I begin to understand his mood. Mum. I touch his wrist and nod, sympathetically. No one could ask for a trickier in-law, even in better circumstances; I love her, but that much even I admit.

There’s more, of course. I see it in his hesitation. Something has happened. Something bad or, at the very least, concerning. But I won’t rush him. He’ll tell me when he’s ready.

We sit in silence, stirring our tea. It’s ten months today since my sister’s death.

Alfie

Julia eyes me across the table. It’s a funny word, eyeing, but that’s what it feels like. It’s something more invasive than looking. Her stone-blue eyes are questing, questioning. She has the look of a poised cat who can swivel her ears towards sound without tilting her head. What does she want from me?

She wants me to carry on talking.

Ah, yes. Marian. This morning.

I gulp some tea – black – and burn my tongue. We only had enough milk for one, something that never happened when Pippa was alive. Or maybe it did, and I just don’t remember, which is even worse.

Where to begin?

With the bell, rousing me from a sticky sleep. I’d been dozing in front of the telly with the girls, marinating in sadness. My sadness, for the girls were no more or less sad than usual. Why should they have been? They didn’t know that today was the first of the month. Or if they did, it meant nothing to them. The sun had still risen in the morning, and I was still the only parent they had left. To them, today was just another day. That’s what I told myself when they asked if they could watch cartoons.

‘Of course we can,’ I said. But then I turned the volume of the telly right down, as if a sick relative were in the room, so they knew that something was wrong. Saying nothing, they snuggled with me and watched the near-silent screen while I dozed and drew comfort from the heat of their small, perfect bodies. I was being selfish, but I couldn’t help it. It was the first of the month, we had nothing to do, and the most important person in the world was dead. It felt wrong that they were running cartoons on TV.

When the bell rang, I didn’t want to answer it. I didn’t want to move, think or talk, and I didn’t care who it was. But it rang again, piercing and insistent, so I swabbed the dribble off my chin, tidied the living room, and then finally answered the door – hopeful that whoever it was would have given up and gone away.

When I realised it was Marian, I only wished I’d waited longer.

Should I tell Julia that? I’m about to, but then reconsider. Julia and Marian have always been close. Not affectionate or tender, perhaps. But close.

I stick to narrating the bald facts. I keep my resentments to myself.

There she stood, breathless on the doorstep, her cheeks pinched and raw in the cold air, her greying hair wild and on end. Wreathed in black furs, she clutched a bulky basket, full of misshapen jam tarts.

‘Grandma’s here,’ I called out weakly to the twins, before deciding that would do for hello. Retreating into the darkness of the hallway, I waited for Marian to follow.

‘Oh Alfie,’ she said, voice wavering as she stepped over the threshold, groping for my hand. It would almost have been moving, had she and Pippa not detested each other quite so nakedly when Pippa was alive.

I led her dutifully into the living room. Before the accident, we’d get the same wistful remark whenever she walked on the mahogany floorboards – This room looked so much better with a carpet – but today we were spared that. Instead, she simply staggered through the doorway and collapsed onto the sofa, exhaling loudly, her limbs jutting out like a wet crow’s feathers. It’s petty, but I was gratified that neither of the twins had responded to my call. Even upon their grandmother’s sharp descent onto the sofa, their eyes remained glued to the television.

‘You don’t mind,’ she said to me breathlessly – a statement, not a question – ‘me stopping by the house.’

The house. That’s what Marian has always called it. Not your house, the house. When Pippa was alive, it didn’t matter. It was Pip’s family home, after all – the house where she and Julia had grown up. But now that she’s gone, it’s starting to sting.

Chickens coming home to roost. When Marian offered to sell us Hart House, we knew what the trade-off would be, and we could have said no. But with two small children, and jobs that fulfilled us rather than paid well, it was the only way we could afford to live in London. Marian gave us an excellent price and, in exchange, she came round whenever she pleased; made us feel like guests in our own home; criticised every tweak we made to the décor. We never agreed to those terms. Pre-sale, they were all unspoken. But still, we never complained. We’d known what Marian was like when we signed the contract. We never felt we’d been tricked.

If anything, it was the opposite: the guilt was all ours, and it pricked especially when Marian reminded us, always with tears in her eyes, of the reason she’d been forced to sell us her beloved home. Marian had been widowed by the age of forty, and suffered a stroke by the age of fifty, leaving her plagued by headaches, joint pain and chronic fatigue. Both her daughters had flown the nest. When Sue, her sister-in-law, who’d been lonely for years, offered her companionship, Marian felt she’d no choice but to go.

Julia’s mug is cooling at last. She holds it, obscuring a few stubborn stars, and begins to drink in earnest. Not for the first time, I feel an urge to confide in her – to explain how Marian’s refusal to acknowledge that Hart House is no longer hers is starting to sting. When Pippa was alive, I belonged here because she did. But now, every ‘the’ from Marian’s lips makes me feel unwelcome. Like I’m an outsider. Like it’s time for me to pack up and leave.

What would Julia say to that?

She’d reach across the kitchen table and squeeze my hand. She’d tell me I was being silly – paranoid, even.

Yes. But what would she be thinking?

That Hart House was her inheritance. That Pippa and I had got it for a snip. That it wasn’t rightfully mine. That it never would be.

That’s paranoia too, I realise. Julia would never think like that. For one thing, the girls have always loved Hart House – perhaps more than any of us – and I belong wherever they do. All the same, I steady myself, and confide nothing.

Marian – still being ignored by the twins.

‘Well? How are my little angels?’

In my exhaustion I, boringly, did the right thing and thumbed the remote. TV off, the twins gave Marian their full attention. They hugged her, kissed her, and prised the basket of jam tarts expertly from her wrinkly fingers.

‘A bit of help for you, Alfie dear. You must be really struggling.’

I lifted the basket out of the girls’ reach. ‘Thanks. We’re doing fine.’

‘Philippa was such a wonderful cook,’ Marian said.

Yes, I thought, airlifting the tarts to safety, largely because she wasn’t taught by you, and a picture popped into my head of Pippa stifling a smirk that made me want to cry. Pippa always said that her mother had witch-like powers: not only did Marian burn everything she cooked, she had an unnerving ability to make others burn their food too. Sometimes she would turn up unannounced on our doorstep around dinner time, disrupting Pippa’s cooking at the pivotal moment. Other days, she would telephone at breakfast and detain her daughter just long enough that ribbons of black smoke began to unfurl from the toaster, making the twins shriek. Oddly, though, the tarts looked fine. Tempting, even.

‘Susan’s been such a help,’ Marian said, revealing the tarts’ true source, and right on cue her eyes began to fill, her irises blurring in a ghostly, watery hue. ‘Everyone has. Everyone’s been so kind . . .’

‘I’m sure.’

I could almost hear their voices. Poor Marian . . . Her daughter dead so young . . . And after losing Eric too . . . So awful . . . Oh yes, unspeakable . . . Poor Marian . . . Mm, yes, poor Marian . . .

Poor Marian. Black furs and tears were mere residue of the figure she had cut ten months ago, at Pippa’s funeral. Like a mummer playing a character in a morality play – Lamentation, Misery, Without Hope – Marian had shivered and swayed, head to toe in pitch-black cloth. When I tried to give the eulogy, it was drowned beneath the weight of her wails. The church was too small. No one else’s grief could fit.

‘They’re not a meal, mind,’ she continued. ‘They’re a snack. The tarts.’

‘Yes.’

‘My girls are eating full meals, aren’t they?’

The house. My girls. I drew a deep breath, and reminded myself that it was all in my head. ‘Of course they are,’ I said.

‘Of course they are . . .’ Marian murmured the words back to me as if barely conscious of their meaning. She was still breathing unevenly, but she’d fought off the tears and her eyes were once again focused and clear. Silently, her gaze roved across the stacks of books that I had hastily constructed, and lingered on the dust that had been displaced.

‘And the cleaning . . . ?’

‘All in hand,’ I lied. ‘I’m hoovering this afternoon.’

At last she exhaled properly and lay back on the sofa, closing her eyes and nodding in approval.

‘I’ll stick the kettle on,’ I said.

And at that, her eyes flicked open again, and instantly refilled with tears. She clasped the twins close to her. ‘If only she could see you now . . . Philippa, I mean. She’d be so proud of you three. I just know it.’

She hated being called Philippa, and she hated you, I thought.

‘Thanks, Marian,’ I said.

Julia’s tea is finished. Or cold. She’s stopped drinking, at any rate, and her expression is tight and tense, which confuses me. I’ve rambled on about her mother’s visit for a good ten minutes, delicately avoiding full-on criticism, only ever hinting at annoyance. A model of diplomacy, or so I thought. Her face suggests otherwise.

‘What’s wrong?’

‘Nothing,’ she says. ‘It’s just . . .’ She hesitates. ‘I don’t understand, that’s all. Why have you asked me here?’

‘Oh,’ I say. ‘Do I need a reason?’ I must look crestfallen – crushed, even – because she swiftly backpedals.

‘Of course not,’ she says, before lowering her voice, I assume not to wake the girls. ‘I’m sorry. I didn’t mean—’

‘It’s fine.’

She scans my face, foraging for something. ‘It’s just that I know there’s a problem. I could hear it when you called. Don’t sugar-coat it, please. Just tell me.’ Now she looks grim, as though steeling herself. ‘What did she do?’

‘Who? Marian? Oh, God. Nothing at all. It was . . .’ I grasp for the right words. ‘The tarts.’

Julia’s eyebrows jump. ‘The tarts?’

As soon as Marian left, all eyes fell upon them. The twins have only just turned seven and stand a little over four feet tall. The top kitchen shelf, where I’d placed the basket, remains, for now, just out of reach.

‘Daddy?’

‘Yes?’

The twins exchanged a glance, which is all it ever takes to synchronise their speech, and seemingly their thoughts. ‘Can we have one now?’

‘No,’ I said, naturally. It was almost lunchtime. But then I thought about how good they’d been with Marian, and how much I loved them, and how their mum was dead, and I gave in. ‘Well, all right. Just the one.’

‘Each?’

I turned and reached up towards the magic shelf. ‘One each.’

‘One each, and one for Black Mamba.’

And there it was. I’d never heard that name before in my life, and, because my back was turned, I had no clue which girl had said it.

I turned to face them. ‘One for who?’

‘Black Mamba.’ This time the twins spoke together again, in near perfect unison, as they have since they were little. Pippa and I were used to it. Only strangers found it unnerving.

‘What,’ I said slowly, ‘like the snake?’

They nodded and smiled.

‘He’s our friend,’ said Sylvie.

‘You can’t see him,’ said Cassia, ‘because he doesn’t want you to.’

The basket was now in my hands; the girls’ palms extended in my direction. Their demand for an extra tart for their invisible friend hung in the air. I handed them one each. ‘Snakes don’t eat pastry,’ I said firmly, and kissed them on the tops of their heads.

Sylvie seemed satisfied, but Cassia kept her palm outstretched. ‘What do they eat then?’

I sighed. The thought of admitting my ignorance, and shattering the precious illusion of a father’s omniscience, felt impossibly heavy. So I said, ‘All right then,’ thinking again that their mum was dead, and little else mattered. ‘One for Black Mamba.’

Julia

‘Black Mamba?’ The words feel peculiar on my lips. Exotic, yet familiar; strangely fallen out of place.

‘Yes. I looked inside their bags. They’ve been learning about snakes at school. I guess he’s . . . an imaginary friend.’ Alfie speaks slowly. His worry is palpable in every breath, but a hardness is setting in. He’s sitting up straighter in his chair, and his thick arms are tightly folded. It’s my fault – I shouldn’t have been impatient; asking him outright why he’d summoned me here.

Fine, he’s thinking, you didn’t want to come. You don’t want to help. No need to make it quite so obvious.

‘Are you asking me what I think as an auntie?’ I say. ‘Or do you want my professional opinion?’

He shrugs. ‘Either. Both.’

I try not to sigh. It wouldn’t be productive. And besides, maybe he’s right to be annoyed. True, he summoned me – but it was my choice to come. ‘Lots of kids have imaginary friends. It’s a normal part of play.’ I lean forward, squeeze his wrist. ‘I’m sure it’s hard to see them playing again. Isn’t it?’

Silence. And then, stiffly, he nods. He’s not exactly laying his vulnerabilities bare, but he is, at last, showing some ankle.

‘I understand,’ I say, emboldened. ‘I see it all the time. Among parents I work with – bereaved parents. You try so hard to cheer your kids up, to help them bounce back, and when they actually do, it hurts like hell. I get it. I really do.’

‘I’m sure,’ he says, withdrawing his wrist.

There’s nothing I can say to that. I know he’s still angry with me for ducking out on him when Pippa died. After the accident, Alfie had wanted me to counsel the girls, and Mum badgered me on his behalf whenever I saw her. You’re a family therapist, for heaven’s sake. You’ve helped hundreds of kids. Why not your own flesh and blood?

I just couldn’t. It wasn’t about ethics, or my own well-being. Even when I was steady enough to start seeing clients again, I refused to treat my nieces. I needed to hold them, and Alfie – and Hart House – at arm’s length. Mum’s never understood, and I’ve never explained it. How could I? Where would I begin?

Alfie rubs his face and sighs, his body loosening. ‘I’m sorry,’ he says at last. ‘It’s just not like them. They’ve never . . .’

‘What? Had an imaginary friend?’

He pauses, then says decisively, ‘Yes.’

I shouldn’t have jumped in. He was going to say something else. The golden rule with clients is to let them speak; force them to find their own words.

‘Not once, ever,’ he continues. ‘It’s not like them.’

I feel myself frown. There must be something else that’s upset him. ‘They used to play make-believe, though, didn’t they? When they were younger.’

‘You know they did.’ His tone isn’t angry, as such. Just cold. ‘Before Pippa died.’

Ah, I think. Is that it?

Pippa.

My sister always loved playing make-believe. When she had kids, it made her a natural with them. I close my eyes, and a series of memories – still images – whirr before me, like frames on one of Dad’s old photo reels.

Click. There’s Pippa and the twins, crouched in the courtyard behind the house, playing shopkeepers. The girls are tiny, maybe two or three. Their blonde hair, in coils, sits like icing on the tops of their heads, and their tiny pink fingers are a blur – frozen in a flurry of movement, busily dishing out rubber vegetables in exchange for plastic coins.

Click. The girls are older now, four or five maybe, and their hair has darkened, becoming wild and unbrushed – and there’s Pippa, smiling at them, lying in Peter’s Park, her own hair blending with the long grass. Bright streaks of paint adorn all three of their faces; I remember that because Pippa painted my face too. We were playing Queens of the Amazon, warrior princesses, leaders of tribes.

Click. Now the girls are older still, six or thereabouts, and they’re indoors, in the kitchen where Alfie and I are sitting at this very moment. A stuffed toy is lying on the kitchen table, a white polar bear, and the girls are wearing thick winter coats, fur-lined, with the hoods up. Pippa has a bowl of water in her hands, and a damp cloth. They’re scientists – I remember suddenly – scientists on an expedition to the Arctic, tending to an injured bear.

I’m close to tears as the camera in my mind’s eye whirrs again. I know what the final image will be: the last game of make-believe that Pippa ever played, just moments before the accident. I want to see it. I don’t want to see it. I want to see it.

Click.

‘Auntie Julia?’

My eyes snap open and I hear feet on the stairs. Sorry, I mouth to Alfie, and he shrugs. I was right: my voice did wake the girls.

We rise abruptly, our chairs scraping against the kitchen floor. Sylvie and Cassia rush in, still wearing their pyjamas: matching onesies, already too small for them. Blue cotton, dotted with gambolling lambs; a present from my mother at Christmas.

‘Auntie Julia!’

We cuddle, and I feel the lingering warmth from their beds. The girls seem bigger than when I hugged them last, and the predictable guilt envelops me. Still, it’s a wonderful hug.

Sylvie pulls away first. ‘What are you doing here?’

Her face looks different too. Some of her freckles have faded, and a little puppy fat has been shed, sharpening her cheeks. Aside from their blonde hair, the girls have never much resembled Alfie, but the more they mature, the more they look like their mum; the more they look like me.

‘I’ve come to see your dad.’

Sylvie tosses her hair, harrumphs. ‘Him? But what about us?’

‘We’ve missed you.’ Cassia’s voice is gentle. She doesn’t let go of me, but she loosens her grip, and tilts back her head until her clear blue eyes meet mine. When the twins were tiny, and Sylvie would cry incessantly – always wriggling; her little body forever becoming too hot and itchy – Cassia was Pippa’s salvation. She was so placid, so quiet and still. Even after the terrible twos were over and Sylvie mellowed, those reputations stuck. Cassia was the calm one, Pippa’s rock; Sylvie was the handful Alfie indulged. I’ve always tried to treat them equally.

‘I’m sorry. I was going to check on you. I promise.’ A little reluctantly, Cassia allows me to prise myself free from her embrace. I take both girls firmly by the hand. ‘Come on. Let’s get you back to bed.’

The girls nod, chewing at the ends of their wispy blonde hair. I look at them closely, but nothing about their expressions or behaviour seems unusual, nothing that helps me understand their dad’s concern. I walk them back up the stairs and Alfie trails us, like a shadow – big and awkward, not fitting in with the three of us; not seeming to want to. I hear his soft breathing behind me and my arm hairs rise like spindles.

Hart House is big enough for the twins to each have a room of their own, but they’ve always shared, and they say they always will. Their bedroom is on the first floor; it’s the one I shared with my twin, when we were little.

Pippa. It’s pointless to compare my grief with Alfie’s, but it is different. The bond between twins isn’t a myth, and losing mine is a layer of pain he cannot see. I open the bedroom door and my gaze is drawn, instantly, to the wide window and the view outside – unchanged since the day I left it. Peter’s Park is dense with trees, which, from this height, crowd out the flowers from view: sycamores and weighty magnolias and, just in sight, at the park’s far edge, the red horse chestnuts, beneath which Pippa fell ill. I tread hastily towards the window, which I note, with momentary surprise, has been left ajar. Moonlight is pouring in; the treetops are swaying in the night breeze. I glance at the twins.

‘Did you open this?’

They shake their heads, watching me silently as I pull it to, and draw the curtains. Then I usher the girls back into bed and pull the covers to their chins. The blue swirls of the duvet undulate as they snuggle and nest. Alfie sits on one side of the bed, I on the other. Tucking them in doesn’t feel strange; I’ve done it before, a thousand times. When they were tiny, I was babysitter-in-chief. The girls would come to stay with me and Mum, when I still lived here with her; they’d fall asleep in this very room. But tucking them in with Alfie, in my sister’s place . . . I kiss my nieces on the tops of their heads. Their hair smells different too. Once it had the scent of crushed flowers; now it smells of cheap shampoo. Alfie’s not hard up, just lacking in knowledge, so this is another casualty of the accident, albeit a minor one. I’m sure the girls haven’t even noticed.

They share a double bed, the same one I shared with Pippa when we were small. Just as they’ve never wanted separate rooms, they’ve never wanted singles. I switch on the side lamp, illuminating the girls’ faces in soft amber light, filtered through the cloth of the lampshade. It makes their hair look dark and bright at once – like cords of black and gold, threaded together – and the walls of the bedroom, which are plastered with the girls’ drawings and sketches, are tinged in a gentle orange glow, as though the four of us are huddled in a fire-lit cave, primitive etchings surrounding us like we’re a stone-age family.

I should wait till tomorrow to question them. When the conditions are better; when we’re all less tired. But the window being open has unnerved me, and Alfie, judging by his shallow breath, is still on edge – so I smooth the covers down over their bodies and smile, implacably. Game face on: firm auntie and shrink, melded into one.

‘So,’ I say. ‘Your dad tells me you’ve made a friend.’ The twins’ eyes are inscrutable. I broaden my smile and continue. ‘Black Mamba. Tell me about him.’

They glance at each other. To confer, the twins never need to speak. A look is always enough. Even when they were very young, decisions about what toys to play with, which children to sit with, whether to stay in a room or leave it, whether to comply with a demand or resist, could all be made through a momentary locking of eyes.

‘What do you want to know?’ they answer in unison.

‘Well, he’s a snake, yes? A hissing, slithering snake.’

They smile and nod, enjoying my playfulness.

I furrow my brow, exaggeratedly, and endeavour to keep my tone mild. ‘Can he talk?’

‘He can talk to us,’ Sylvie says swiftly. ‘He can talk without moving his lips.’

‘He sounds clever. And how did he get into the house?’

Sylvie blinks, seemingly uncertain. She turns to her sister.

‘Why, through the door, of course,’ Cassia says quietly. Her mouth is twitching slightly, as though she’s tickled by her own private joke.

‘Not through the window?’

‘Of course not,’ she says, still smirking.

‘Of course not,’ I repeat. ‘Silly me. He sounds amazing. Although . . .’ I shake my head, screwing up my face, as though suddenly wracked with concern.

‘What? What?’

‘Well, he is a snake, isn’t he? And snakes can be scary. Aren’t you scared of him?’

Without hesitation, they shake their heads. ‘We like him. And he likes us. He wants to stay.’

‘Oh, so he’s here now?’

‘Yes.’

‘But it’s bedtime. Don’t you think it’s time for him to leave?’

They turn to Alfie. ‘Can’t he stay, Daddy?’ Perhaps it’s my imagination, but I think I hear a change in Sylvie’s voice – suddenly it’s more high-pitched, more babyish. The problem is never that a parent has a favourite; it’s that their children know it.

Alfie doesn’t answer, so I switch off the side light and kiss the girls one last time. ‘Good night, angels.’

He leans in and kisses them too. ‘Nighty night.’

We head towards the door.

‘Please, Daddy,’ Sylvie wheedles in the dark. ‘Can he stay? Just for a bit. Like a sleepover, with a friend.’

That’s it, I think instantly. That’s what I’ve been missing. The source of Alfie’s unease.

‘Of course,’ he whispers back. ‘A friend of yours is a friend of mine. He can stay as long as you like.’ He reaches forward to close the door. ‘Sweet dreams.’

As soon as it’s shut, I say it aloud: ‘It’s not the fact that he’s imaginary, is it? It’s the fact that he’s a friend.’

Alfie laughs hollowly and nods. ‘Stupid, isn’t it?’

The girls have never had friends, not really. They’re rarely invited to birthday parties or sleepovers. They’ve always been insular, uninterested in anyone except each other. Whilst Pippa and I yearned, from an early age, for a life outside the walls of Hart House – a life beyond each other – Sylvie and Cassia have never seemed to have that need. Pippa loved them more than anything, and they loved her too, of course, but they always loved each other more.

‘It’s who they are, Jewel,’ she used to say, dreamily, if I ever queried it. ‘They’re more alike than you and I ever were. They’re like two halves of one whole. They’re two people and one person at once.’

And now they have a friend.

‘Did I do the right thing?’

We’re retreating down the stairs now, quietly – I more quietly than him. After all these years, I still remember every board that creaks.

‘About what?’

‘Black Mamba. Was I right to say that he could stay? Should I be playing along?’ I reach the bottom, and turn to find Alfie at a halt, three steps up, one arm resting on the bannister.

‘Sure. I see no harm in it.’

With his free arm, he runs his fingers through his sandy hair. ‘What do snakes eat, anyway?’

‘They’re carnivorous. Small mammals, that kind of thing.’ I fetch my bag from the kitchen, then return to the hallway for the rest of my things. ‘Thanks for the tea,’ I say, shrugging on my coat.

He’s still by the bannister, but staring at the walls now, deep in thought, only dimly aware that I’m still present. I put on my scarf. I know we won’t see each other again for a while, a few weeks at least. We’re always at our worst around each other. Maybe we won’t see each other again until next month. Until the first.

‘Are you leaving?’ Suddenly, he’s out of his reverie, and there’s an urgency in his voice that perturbs me. ‘There’s one more thing.’

I’ve already turned to go.

‘It’s probably nothing.’

Somehow – I don’t quite know how – I sense what he’s going to say.

‘This isn’t the first strange thing they’ve said. About a month ago, they went through a phase of having nightmares.’

‘Nightmares?’ The adrenaline heightens my voice, but I keep it steady, just about.

‘Yes.’ There’s a long, sick silence. ‘They said there was a man in their room.’

And there it is.

‘I’m sure you’re right – it’s nothing,’ I say. ‘I have to go.’

‘Julia?’ Alfie’s voice rises, in confusion and concern – but I’m already gone, out of the front door and into the cold night air. The door slams shut behind me, echoing through the square. I rush towards my car, mind reeling. I’m never coming back, I think, though I know I’m coming back. I have to now.

I open the car door and fall inside. It’s colder outside, but the cold inside feels worse: clammy and still. ‘Oh God,’ I moan, leaning forward onto the steering wheel. ‘Oh God, oh God.’

It’s happening again.

Two

Alfie

We were happy here once, and the twins were happiest of all. Even from the youngest age, they adored Hart House. ‘It’s special,’ they’d insist, and we never demurred.

Every floor of Hart House is slender and pinched, its rooms all squashed together, but the building itself is tall, impossibly tall, with a winding staircase driven through its centre like a screw in a press. The house is crowned by a tiny attic and a terrace, and the master bedroom, on the top floor, has a skylight, through which Pippa and I would watch clouds drift by, or count the stars, or, during summer, lie in wait for a plane to bisect the brilliant blue. When the girls were out with Marian or Julia, we’d pull ourselves up through it and sit on the terrace. On hot days, we’d drink cold beer, and sometimes I’d stand, knees shaking, and lean against the baking tiles of the attic roof, to take in the view: Peter’s Park, lounging before us like a paradise, and around it, endless rings of houses, stretching all the way to the city skyline.

‘It’s beautiful,’ I’d say. ‘Come, look.’ But Pippa never would; she couldn’t bear to touch the attic roof. So what if she hadn’t seen with her own eyes what happened in there? She knew.