Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Birlinn

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

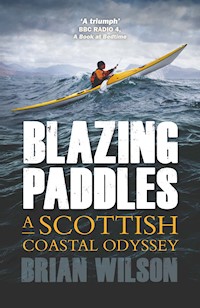

Alone in his kayak, Brian Wilson sets off from the Solway Firth on a 2000-mile odyssey around Scotland's extraordinarily varied coastline of cliffscapes, unspoiled shorelines, treacherous sea passages and beautiful Hebridean islands. Adventure is there aplenty as he battles with whirlpools, heavy seas and hypothermia and survives a close encounter with a killer whale. During the voyage, which finishes on the East Lothian coast at Seacliff, he meets a colourful cast of characters, including the larger-than-life famous shark hunter, Tex Geddes, Dr Stan the cave-dweller and even streaks naked in front of the Princess of Wales. Sometimes harrowing, frequently philosophical, and often hilarious, Blazing Paddles is also a perceptive commentary on the environmental issues which threaten the Scottish coastline and its unique and fragile wildlife.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 432

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2019

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

This one is for Eskimo Nell, with love

This edition published in 2019 byBirlinn LimitedWest Newington House10 Newington RoadEdinburghEH9 1QS

www.birlinn.co.uk

First published in 1988 by The Oxford Illustrated Press; second edition published in 1998 by The Wildland Press; third edition published by Two Ravens Press in 2008.

Copyright © Brian Wilson 1988, 1998, 2008, 2019

The moral right of Brian Wilson to be identified as author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patent Act, 1988.

ISBN 978 178885 202 9

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data. A catalogue record for this book can be obtained from the British Library.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored or transmitted in any other form without the prior written permission of the publishers.

Typeset by Geethik, India.Printed by Clays Ltd, Elcograf, S.p.A

Contents

Introduction to the Fourth Edition

1. ‘Just Add Water’

2. Flotsam, Jetsam and Me

3. Wet, Wet Wet!

4. ‘… Malin, Hebrides, Minches …’

5. Sharks, Midges and Maidens

6. Machair and Traigh

7. Dragons, Elves and Killer Whales

8. Turn Right at Cape Wrath

9. Foul of Eastern Promise

10. Coasting to the Finish

Introduction to the Fourth Edition

This edition of Blazing Paddles marks the passing of three decades since, at the age of 22, I launched a small kayak, hoping to paddle it right around the coast of the country that was, and remains, my home. I didn’t need to be the first, or the fastest; it wasn’t about staking a claim. I simply wanted to travel as a self-contained unit – independent of the land and sea support that often accompanies similar ventures – and to explore and discover the whole Scottish coastline, its people and its wildlife, to make it my own. Travelling alone, by kayak – portable, vulnerable, seaworthy, quiet – seemed to me the best possible way to do this.

The journey itself (1,800 miles in four months) was to become a personal awakening, almost a rite of passage. There were periods of intense physical challenge, moments of sublime peace, emotional highs and lows – fear, loneliness, elation – even days when I thought I might die! And by the end I had become a very different person.

One can’t travel on the sea for four months, living in tents and caves, sleeping on beaches, without developing an acute awareness of the intricate ecology of the sea and shore. And along with that awareness comes a concern about everything which threatens its diversity and health. So it was that submarines, supertankers and sea pollution found their way into the fabric of this story.

I hoped (back in 1985) that wider appreciation of some of the issues involved might encourage more open discussion and help people who love the sea to exert more effective pressure towards its sane and sustainable management. And perhaps, to some extent, it did. Sadly, however, many of the problems that I was beginning to worry about as a young traveller have today become major international environmental concerns. Some, indeed, are approaching catastrophe level.

Scotland is home to more than 40,000 species of marine wildlife. Our coasts and seas host a third of the world’s population of grey seals, a third of all whale and dolphin species, and the highest number of porpoises in Europe. We have the world’s largest colony of northern gannets, the UK’s biggest stronghold of puffins, the most northerly pod of bottlenose dolphins and some of the finest sub-marine habitats in Europe. In addition, Scotland is the best place on the planet to see basking sharks, making us one of Europe’s finest ecotourism destinations. All of which is big business, and a huge stewardship challenge. And all of which is currently facing a range of serious problems.

Fish farms crowd the sheltered bays of the Atlantic seaboard, polluting our tides and sea beds with chemical effluents and infecting wild fish stocks with lice and diseases. Industrial ships dredge the sea bed indiscriminately in pursuit of shellfish, leaving wrecked habitats in their wake. The seabirds which once crowded the great cliffs and skerries are today struggling desperately with pollution, overfishing and the effects of a changing climate. Many of their roosts – once raucous festivals of life – have become lonely, subdued places.

When change and decline are gradual, their impact in the short term is hardly noticeable. A 3 per cent reduction in bird numbers each year may be almost invisible to the casual observer, and many of our seabird sites are remote, and seasonal, seen only by occasional visitors. But the majestic spectacle of a major seabird colony is already gradually becoming a distant memory. All the more tragic, as future generations are unlikely to miss what they never knew.

Globally, seabird populations have dropped by around 70 per cent in the past 60 years. Half of all known seabird species are in decline, with a full third facing possible extinction. There are a billion fewer seabirds now than in 1950, with many species plotted on a population graph trending towards zero by 2060.

In European waters, fulmars are down 40 per cent in the last 30 years, kittiwakes may have lost around double those numbers. Atlantic puffins – those ever-popular sea parrots of the northern seas – are under enormous pressures from climate change. With the disappearance of their feedstocks, their numbers will be down to a fifth of what they once were by the middle of this century, thereby becoming a very rare sight anywhere south of the Orkneys.

These are declines for which we are responsible. Human overfishing has much to answer for. (Research has shown that if fishing boats take any more than two-thirds of the available fish stocks, the seabirds begin to die.) But there are many other factors at work here.

Massive numbers of seabirds are destroyed ‘accidentally’ by fishing gear. Even after it is discarded or lost, it can continue to ‘ghost fish’, catching and killing birds, fish and mammals for many years. Pollution of the seas – oils, metals, plastics, PCBs and other toxins from human activities – takes a constant and devastating toll on seabirds. As do the disturbance and destruction of habitat, the introduction of predators to bird breeding sites, and the ongoing effects of climate change and ocean acidification.

All over the world, measures are being taken in an attempt to avert seabird decline. Projects to eradicate alien ground predators (rats, mink, hedgehogs), especially on islands, have been very effective. There have been schemes and initiatives to reduce accidental by-catch and to limit the shooting of seabirds. But at current levels of intervention seabirds continue to tumble towards the abyss. There is no time left for complacency – for blaming the seabird losses on normal oscillations in the ocean ecosystems. Seabird decline is a visible sign that the entire web of marine life may be in jeopardy. Much more must be done, and urgently. Crucially, we must acknowledge that the rate at which we are changing the atmosphere and the oceans – their temperature, acidity and cleanliness, use and management – needs to be brought under tighter control.

The bountiful mounds of driftwood and wooden fishboxes, which once comfortably fuelled and furnished the camp spots of a coastal nomad, no longer wash up on our western beaches, having been superseded by generations of polystyrene and bright indestructible plastics. From the elemental sea-salts to the bellies of the greatest whales, particles of plastic now pervade the entire marine ecosystem.

Plastic pollution, of course, is neither a recent, nor just a Scottish problem. Plastics have been found in all the oceans – from the poles to the tropics – and even in the deepest oceanic trenches. Phenomena such as the ‘great pacific garbage patch’ have become infamous. With an estimated 12 million tonnes of plastic getting into the world’s oceans every year, the issue is at last creating international headlines and entering human awareness worldwide. Impacts of plastic in our ecosystems range from unsightly littering of our coastlines, through entanglement and physical harm to wildlife, down to insidious, far-reaching, long-term damage to habitats, food chains and human health. It has been estimated that by 2050 there will be more plastics than fish in the world’s oceans.

Recent media coverage (most notably David Attenborough’s excellent Blue Planet 2) has fed into a growing public backlash against wasteful use of plastics. Beach-cleans and plastic removal are enormously important initiatives, both in terms of clean-up and in raising awareness. But, in the absence of a miraculous technological solution, ocean-borne plastics are going to be a fact of life for the foreseeable future and much remains to be done. The flow of plastics into the oceans needs to be stemmed at source.

All can contribute to tackling this crisis – governments, drinks companies, the cosmetics industry – but it is up to us, consumers and voters, to demand it loudly, and then we must actively support the changes.

Of course, not all is gloom and disaster; much of what I enjoyed in 1985 continues unchanged. The Scottish coastline remains one of the most magical, unspoiled places in the world for relaxation and discovery, exploration and adventure. And there exists today a growing awareness of the need to protect the precious natural richness around us. The great swell-waves still pile in upon our shores from the wide Atlantic; strong tides scour and swish through the island narrows; impressive numbers of plucky seabirds still return to their rocky outposts each spring; and the flowers of summer still crowd the Hebridean machair-lands.

Blazing Paddles was a lone foray into less-travelled areas, both geographically and personally. But the very concepts of solitude and wilderness – which lie at the heart of the journey – are themselves changing quickly: a tsunami of miniaturised digital technology has, in the intervening years, transformed adventure travel. True solitude dissolves when we choose to carry a reliable means of contacting (or being contacted by) the outside world. And the idea of wilderness recedes in direct proportion to the quantity of technical bling we choose to bring with us in pursuit of it.

‘The past is a foreign country. They do things differently there,’ wrote L.P. Hartley. But as Blazing Paddles relaunches, in its fourth edition, I like to think of it reaching out to a new generation of coastal adventurers, and also continuing to touch the hearts of those who care about the salty places where land and sea combine. It’s probably best enjoyed with a generous dram, on a beach, by a driftwood fire, possibly as a narrative record of a time which is rapidly passing, but, above all, it is a portrait of a young man’s first low-tech voyage of discovery, floating boldly alone among the seabirds and fishboxes of a very special country.

For further information, campaigns and lobbying, support:

Ellen MacArthur Foundation –

www.ellenmacarthurfoundation.org

Greenpeace – www.greenpeace.org.uk

Marine Conservation Society – www.mcsuk.org

Friends of the Earth – www.friendsoftheearth.uk

John Muir Trust – www.johnmuirtrust.org

Sea Change – http://seachangewesterross.co.uk/about-us/

The Scottish Salmon Company – www.scottishsalmon.com

Brian WilsonUllapool, 2019

1

‘Just Add Water’

‘Two thousand miles at sea in that? Dae ye think I came up the Clyde in a banana boat?’ said the cynical Glaswegian, not quite convinced by my attempts at an explanation. It’s one of the most picturesque phrases in ‘the patter’, referring to the naïve and city-stunned crews of early trading boats, but its origins are lost somewhere in the hazy history of Clydeside. And yet in April 1985, beneath Glasgow’s Victoria Bridge, it was inadvertently given a new life and meaning. For my kayak Natural Crunch, billed by Radio Scotland as ‘a modern marine anomaly’, was indeed a ‘banana boat’; a kayak of bright yellow fibreglass whose pointed ends curled gracefully upwards in a fair approximation of Eskimo nautical engineering, and bearing exact resemblance to a great banana. With a ceremonial push it was launched, along with its bewildered Aberdonian cargo, into the Clyde.

Thirty feet above, on the wooden decks of the RNR clubship SVCarrick, reporters, TV cameras and radiomen fussed and jostled for a view; as far as they were concerned this was the start of a long sea journey around Scotland in the eighteen-foot kayak.

Down at water level an old friend, who had become my self-appointed ‘manager’ since hearing that a free bar and buffet were on offer, wobbled precariously in a slowly sinking clinker boat, bailing out frantically with one hand and directing me with the other towards a photographic rendezvous in mid-Clyde.

With a flick of the paddle I sent the slender kayak out across the water and swept a wide arc round towards a tiny orange dinghy drifting, apparently, out of control. The dinghy held three overweight photographers in immaculate suits and carrying neckloads of cameras; like stuffed cuckoos in a waterlogged nest they drifted and spun further and faster downriver as they attempted to master the use of the tiny plastic oars. I approached within camera range and paddled in for the first picture, but the dinghy rotated in the wind so that each had to crane and twist to avoid filling the frame with the others’ ears and balding heads. A second approach and all was well until a mistimed pull on an oar sent their vessel and their lenses spinning out on a 180-degree span of Clydeside. The offending oar floated over towards me and curses echoed over the water like a scene from Jerome K. Jerome’s Three Men in a Boat – and it’s little surprise that next morning’s papers displayed my widest camera grin, for it was all I could do to avoid laughing myself into total capsize.

Meanwhile, in the bar of the Carrick, serious journalistic speculation was in progress. Some tipsy representatives of the less reputable press were putting my girlfriend Pippa’s mind at rest by explaining that they were only interested in the journey if I was to have an affair with royalty or get a seal pregnant en route, and suggesting what fun they would have with the ominous name Natural Crunch when the expedition hit disaster.

My brother, dressed to pass as a pressman, sat with glass in hand, looking suitably replete, in one corner, and sure enough by the time I arrived the buffet had long since been demolished. Drunken reporters gobbled and quaffed wherever I looked, while I was nudged into a prominent position, decked in sponsors’ regalia, and bombarded with questions from a magicube-flashing throng obviously anxious to get the interview on tape and renew intimate professional contact with the bar.

‘What do you think of Jimmy MacGregor calling you “a mad heidbanger”?’ … ‘How can you go “round Scotland” when it’s not an island?’ One misguided soul even congratulated me on ‘winning the Round Britain Yacht Race’!

To a string of questions which lacked any trace of perception of what my journey was to be about, I gave polite and inane answers which were printed next morning word for word. Being the focus of such concentrated attention seemed to bear little relation to the lonely adventure that I was about to embark upon. But accepting sponsorship is never a ‘something for nothing’ situation and, of course, it could have been so much worse. I had firmly refused the earlier photocall requests to pose, one foot on the kayak like a hunter with a slain crocodile, wearing lifejacket, wetsuit and kilt, and to the accompaniment of a piper on the clifftop! The day at the Carrick was a compromise, a chance to fulfil an obligation to my major sponsors, Fox’s, and to publicise the Third World charity Intermediate Technology, for whom the expedition was to raise funds, without prostituting the ultimate privacy of the expedition. Fox’s had understood this; the expedition was still ‘mine’ and the true launch, the following day near Dumfries, would be a private affair untainted by media presence.

In the brief moments of quiet allowed to me as I stripped off the promotion gear in a back room, I thought of the questions that had remained unasked and of what, for me, were the real purposes, reasons and expectations of the journey.

* * *

Long before the age of fourteen, when I floated my first patched battleship of a canoe down the river with a pair of rusty pram wheels strapped on behind to haul it home again, the idea of self-propelled travel by water had me utterly seduced. Why struggle up and down hills with blistered feet and a 60-lb backpack wearing lumps out of your shoulders, or slog along twisted roads with a loaded bike, when you could pack twice as much gear into a kayak, let the water take the strain, and use the current or tide to your advantage?

Throw in a paddle and a sprinkling of basic techniques and you become a master of a craft which makes no noise, gobbles no fuel, leaves no waste, and whose lightness and shallow draught allow it to travel in waters often too treacherous for larger vessels.

Wearing the kayak tightly like a garment, one sits below water level, separated only by a thin shell of fibreglass from the great sweep of the tides and every smaller movement of the sea. But although fragile in appearance, the kayak well-handled is one of the most seaworthy boats in the world. Its manoeuvrability is unrivalled; a whole range of movements is executed from the hips and knees alone. And with skilled use of the paddle the capsized kayak is righted again in seconds.

As an undergraduate in Edinburgh in 1980 I began my first course in sea canoeing. Wednesday afternoons were spent floundering in the freezing surf of the Firth of Forth or paddling nervously out to the Bass Rock, learning the basics but always with bigger things in mind.

Steadily I accumulated the basic skills, learned to calculate and predict the complicated movements of Scotland’s tides, to navigate using map and compass, to Eskimo-roll a capsized kayak and, most importantly, to appreciate my own strengths and weaknesses. Each summer a small group of us headed west for ten days’ kayaking and camping among the islands, making sense of all those Wednesday afternoons and of my little-boy’s belief that it was possible to travel independently and self-sufficiently, by water.

Long days of paddling among idyllic scenery, Hebridean beaches and island campsites began to work in me to create a strong addiction to the Scottish coast and to the freedom afforded by the wandering sea-kayak. But ten days were never long enough and each year, as my experience grew, my resolve strengthened to launch a larger expedition, perhaps of several weeks’ duration.

Back in Edinburgh, Plato, Wittgenstein and Nietzsche shared bookshelf and mind-space with Gavin Maxwell, Neil Gunn and Frank Fraser Darling, and in idle moments the dream evolved until in 1984 I envisaged doing an extended voyage, combining the experiences of several shorter forays, and seeing the Scottish seascapes throughout a range of seasons and conditions. Between bouts of study for final exams in philosophy I took mental refuge in building the journey upon the most adventurous ideas I could conceive. Why not paddle from border to border around the entire coast of Scotland? By including the Outer Hebridean Islands I could increase the distance of the trip to over 1,800 miles, almost equivalent to the entire distance around mainland Britain. Deeply scarred and pitted with sea lochs and host to isolated island groups, the Scottish coastline is literally thousands of miles of bewildering variety in seascape, wildlife and human tradition. Within its compass fall some of the wildest of unspoiled beaches, the grandest of cliffscapes and the most notorious sea passages in all Europe: the Dorus Mor, the whirlpool at Corryvreckan, the Butt of Lewis and the Pentland Firth, and coastal obstacles such as the great headlands at Mull of Galloway, Ardnamurchan and Cape Wrath, all increasing in severity as I passed, clockwise, around the coast. Of course, it would have to be done clockwise, sunwise. In keeping with Celtic mythology, deeds done ‘widdershins’ always ended in disaster. And I could do it alone! All supplies and equipment could be carried in the kayak with no need for land or sea support and virtually no restrictions on destination.

The final concept was of a highly improbable, self-sufficient, solo circumnavigation of the Scottish coast and Hebridean Islands. And at last I was satisfied, for I had created what I believed to be the very paradigm of independence and adventure, the sort of dream one could suck dry for a lifetime. But I had exams to sit and a job to find. I had no money and didn’t even own a kayak! There were plenty of excuses for copping out.

And so months went by in which I added nothing to the dream. I passed my finals and life became real. I taught canoeing and archery in Edinburgh, cycled through France with Pippa, dried hops in Kent and worked at tree surgery in Aberdeen. But as 1984 drew to a close I found myself unemployed and with no real desire to follow friends into mortgages, marriages and secure jobs in the city. The current of life had veered off and left me in a stagnant backwater. I was sinking fast into one of those ruts that dominates one’s character and crushes all motivation, and which is the biggest danger of unemployment. I had neither the awareness to see what was happening nor the power to reverse it until one morning Pippa put her arms around me and with sad eyes said, ‘Brian, you’re becoming depressed, stagnant and cynical. It’s time for you to DO something.’

And it was as though the elf queen had whispered in the ear of a Hobbit for, with the force of sudden revelation, I knew that she was right. Unmarried, unmortgaged and healthy, I was to all intents and purposes as free as ever I would be; and yes, of course, there was a dream to realise. Suddenly, through the love of someone who understood me, the dream was rekindled and I began to throw all my energy into bringing it into being, never stopping to consider whether the aims of that dream were really possible, or to doubt my ability to achieve them.

And so began the long months of preparation that lie behind any expedition. The route had to be decided, maps acquired, distances and timings estimated as accurately as possible. What sort of food should I carry? How much would I need? What would that weigh? Essential canoeing, camping and safety equipment would have to be decided on and purchased. A sea-going canoe would be useful.

What would all this cost? And, most importantly, how the hell was I going to pay for it?

There would be physical preparation too, but at least I was fit. I had won the Scottish Universities ‘Superstars’ contest and taken my second British Universities Judo title earlier in the year. After several months of outdoor employment I had at least a sound basis upon which to build the expedition training.

Before Christmas, using the little money I’d saved, I bought a damaged Nordkapp HM sea kayak and channelled more money into its repair. It was a boat I knew and respected for its seaworthiness and storage capacity. Perhaps not as stable nor as manoeuvrable as some boats, nevertheless it ‘tracked’ well in a rough sea, was fast, sturdy and light.

An initial run of begging letters to equipment and food manufacturers, in my most humble and persuasive prose, brought an almost unanimous response of ‘Dear John’s, ‘sorry’s, and ‘no’s. I was an unknown quantity in the expedition world – not a household name like Bonnington, Fiennes or Clare Francis – and had no leverage with potential sponsor companies. I began to realise that for newspapers and magazines I had to make the expedition sound as hare-brained and spectacular as I dared; for potential sponsors it had to sound exciting but well planned and safe.

So a second draft met with some limited success. Each morning I waited for the post to discover what new package, pledge or promise had arrived to improve the prospects of the trip, and as parcels and letters of encouragement started to flow I began to feel, at last, that I had a real expedition in the offing.

Canoe-equipment manufacturers Harishok and Wildwater sent their blessings along with vital equipment items. Lendal products donated a collapsible spare paddle to be carried in case of emergency and, for performance testing, Timex sent an indestructible waterproof watch with an alarm which played ‘Love Me Tender’ by Elvis.

Damart thoughtfully provided two sets of thermal underwear and Mary Buchanan of Slioch Outdoor Equipment asked for a shockingly intimate set of personal measurements in order to fashion a pair of thermal trousers. The result was without doubt the most fantastic, fleece-lined, curve-hugging garment I’ve ever possessed!

Aberdeen companies BPI, Marconi and Arthur Duthie raised the safety margin of the trip by providing an emergency radio-beacon and hand-held radio on loan, and a veritable arsenal of assorted distress flares.

‘What’s in a name?’ I thought, as I accepted a wetsuit and yet more flares from Aberdeen’s Sub-Sea Services, and agreed to display their stickers, without superstition, on a prominent part of the kayak.

As the equipment list shrank, my room began to resemble Everest Base Camp. Robertsons of Stromness sent fifty bars of Orkney Fudge with best wishes, and Jordans Wholefoods pledged 500 Original Crunchy bars in three flavours. Things were looking good, there were still maps to be bought, more equipment to be found and a balanced diet for five months to be provided.

Food would be an expensive problem. Hundreds of letters requesting financial assistance had already drawn a total blank; the price of stamps alone would have accounted for a week’s good eating. I had to find a source of income, fast.

During January and February I took a job as a night security guard for an oil company office. This gave me time during daylight hours to train, while at night ‘on the job’ I researched and digested everything I could find concerning the Scottish sea, coast and islands. After two weeks I could afford the forty-one OS maps (1:50,000 scale) which cover the coast of Scotland.

I raised my daily running distance to five miles carrying two 3-lb weights, swam half a mile daily and cycled eight miles each way to work. Now the nights consisted of plotting chart information about tidal anomalies and coastal hazards onto OS maps and taking page after page of detailed notes for future reference. I struggled to make myself master of a specialist combination of skills, studying navigation, finalising routes and logistics, translating Gaelic place-names, reading up on first aid and meteorology. Each week I stepped up my training; I began aerobic popmobility and practised, in the kayak, deep-water self-rescue techniques I had seen in a book. But on the morning the company boss arrived early to find his ‘security’ man flaked out and snoring in the executive swivel-chair, surrounded by maps, compasses and bandages, my expedition income came to an abrupt end and the problem of funding again loomed large.

I began to consider the possibility of ‘living off the land’ to a certain extent in order to cut food costs. I had experimented with ‘wild food’ before and began frantically reading anything I could get hold of. Encouraged by Richard Mabey’s comments: ‘The most complicated and intimate relationship which most of us can have with the natural environment is to eat it … to personally follow this relationship through, from the search to the cooking pot, is a more practical lesson than most in the economics of the natural world,’ I began to believe that the economics of the natural world were at least more optimistic than the economics of my world.

In teaching archery I had become fairly accurate with an arrow; could I bring down the occasional rabbit? I could drag a darrow-hook for fish, patrol the ebb shore for shellfish, boil seaweeds, fry silverweed and samphire; the possibilities seemed endless. The only problem would be finding time for canoeing! Despite the latest sponsorship donation – vitamin pills from Sanatogen – I had to admit to clutching at straws, but I wasn’t going to give up the journey at this stage.

In mid-February I began canoe training, doing twenty-fivemile trips in the Nordkapp and, on camping weekends, cavorting around in the surf at Cruden Bay, north of Aberdeen. The North Sea in February is a cruel place and at the end of a day I’d be unable to button my shirt or zip my fly for cold numb hands, but I was happy. My reactions were improving – I could handle ten-foot surf now easily, and the kayak performed well; the repair was strong. New equipment was given a thorough testing. Stamina was good, strength still growing, but most of all those weekends took my mind off the details and financial problems of the expedition.

* * *

1985 was the year in which distended Ethiopian stomachs glared from every TV set as the developed world at last began to feel uncomfortable at its own complacency. The disasters of drought and famine, and the dramatic pictures which they created, were the climax stages of the polarising trends of an even greater disaster, modern international economics. The fast-living, short-sighted production and consumption patterns of the wealthy lead to the ever-greater dependence and alienation of the impoverished and to the ecological rape of the planet. ‘The rich get richer and the poor get poorer’, but it had long been foreseen by many experts whose advice had gone unheeded. Among them was Dr E.F. Schumacher, an economic consultant to the United Nations and author of the influential Small is Beautiful.

The need for emergency famine relief was undeniable, and it became imperative to me to link my expedition to some form of Third World aid. But I was already painfully aware that disaster relief is but an inadequate dressing, applied in panic to a badly infected wound. Schumacher had pointed out, in simple terms for us non-economists, that famine, poverty and environmental destruction will never disappear until the roots of the problems are tackled in an appropriate way. The people of the rural Third World must be given the means, the know-how and the low-cost, small-scale technologies that will enable them ultimately to work themselves out of the vicious circles of poverty and aid, disaster and relief.

Thankfully today many charities have reorientated their aid programmes to acknowledge the importance of long-term development in the Third World, but in 1985 I knew of only one charity pioneering work in this area. Founded in 1965 by Schumacher, the Intermediate Technology Development Group (I.T.) were adapting and developing low-cost tools and methods which could be used in rural areas to cultivate, store and process food, pump and distribute water, construct better homes and to safeguard the fragile environment. By its very nature, the work of I.T. was cutting the bonds of economic dependence and setting rural communities back on their feet.

The principle is often summed up with the adage, ‘If you give a man a fish, you help him for a day; if you teach a man to fish you help him for a lifetime.’ The trouble is that he is dependent, for replacement equipment, on your alien technology and skills. But if you can teach him to make and maintain his own fishing tackle, cheaply and efficiently, you will have helped him to become self-supporting and independent. This, ultimately, is what I.T. is about. On 28 February I travelled to the I.T. offices in London to offer my journey as a fundraising venture.

‘Oh, no, no, NOOO! Not another maniac!’ said Steve Bonnist, I.T.’s long-suffering press officer. A seasoned sufferer of many expeditions, Steve has Run the Himalayas, Cycled up Kilimanjaro and Reached the ‘Centre of the Earth’ in the amazing publicity and fundraising company of the unstoppable Crane family; he has climbed 227 Scottish mountains in one winter and won the Three Peaks Yacht Race … all from the confines of a crowded office in Covent Garden! I hesitate to say ‘comfort’, for Steve’s job of media-hassling, sponsorship-co-ordinating and press-release-writing on behalf of an increasingly influential charity, makes high mountains and heavy seas pale into insignificance.

‘You can’t do this to me,’ said Steve, careworn and weary from the paperwork for Bicycles up Kilimanjaro, but the outrageous schemes of the Cranes had already numbed his better judgement and – despite some initial cynicism – I was soon welcomed aboard the I.T. bandwagon and given the chance to make my journey work for others.

I.T., whose full name would be more suitable to a computer software firm, lacked the emotive appeal of other relief charities. Greater public awareness of the importance of their unique approach to aid and development was therefore, to my mind, their most urgent need. I returned from London convinced that the I.T. linkup was the most worthwhile contribution I could make to Third World aid, and from that point on publicity and media exposure of the aims and methods of Intermediate Technology became an integral part of my plan.

That evening I sat alone in a railway station with a ticket to Aberdeen, drinking tea and enjoying a biscuit. Without really thinking, I turned the wrapper over and scribbled a quick request to the manufacturer for a supply of biscuits. Had I guessed the results of that scruffy note and second-class stamp I’d have probably choked on the biscuit. But when the manufacturers, Fox’s, answered my letter, it was not just with an offer of biscuits, but with a proposal to underwrite the whole financial deficit of the expedition.

Fox’s, in the process of launching a new health-bar biscuit, wanted an adventurous profile for their product. They had also recently been involved in baking the emergency high-energy biscuits for distribution in Ethiopia by Oxfam and other aid groups, and as such they were wholly behind me in any fundraising and publicity for I.T. And so, for the tidy sum of £700, a dowdy kayak became the highly decorated Natural Crunch, a showground of coloured publicity stickers and an evangelical mission for Intermediate Technology.

Suddenly, with money available, it was time to think of what sort of food to take. Packed space and weight were now the main variables. Fox’s had pledged 500 Natural Crunch bars which, along with the Jordans supply and the Orkney Fudge donation, would see me okay for snacks. But there were main meals to consider. A high-energy, nutritious diet would be immensely important to the expedition’s success, but space in the kayak was limited.

I estimated that, carrying a few canned items, some cereals, soups, crispbreads and a wide selection of dehydrated and freeze-dried meals, I could pack up to one month’s supply at a time in the kayak. I ordered Raven dried products in bulk at a reduced price and made up monthly supply boxes, portioning the food and other equipment out evenly. These boxes – which also contained stove fuel, camera film, paperback books, radio and torch batteries, a change of clothes and the appropriate maps, tide-tables and extra equipment – were sent ahead to my estimated positions for the end of each month of the trip: Oban, Uig (Skye), Ullapool and Thurso.

With the supply boxes packed and consigned to their various destinations I was at last ready to launch, fully prepared, fully fit and self-sufficient for one month at a time. And as I packed the final box with the supplies for the initial stage of the journey, the simple instructions on the dehydrated ration packs seemed to underline my readiness with a peculiar relevance. Over and over again they said ‘JUST ADD WATER’.

2

Flotsam, Jetsam and Me

Smiling nervously, I squeezed into the tiny cockpit. Hours of careful packing, and I’d almost forgotten to leave room for me. Never before had I carried supplies for more than a two-week trip, and even then the load had always been shared out among the members of a group. Now I was carrying equipment for a journey which would span three seasons, and I was carrying food for a month at a time. The edible contents of the kayak had to last until I reached Oban, and my next supply box, approximately 300 miles away by sea. The price of the self-contained travelling unit was that it all had to be carried by me.

This first attempt to pack, despite what I considered ruthless editing of the final equipment list, had been utter chaos. With front and rear decks loaded in unorthodox fashion and all the items which stubbornly resisted my attempts to jam them into the waterproof holds below decks, the final result looked more like a pack-mule or a double-decker bus than the sleek business-like craft I’d been so proud of. At 400 lb it was well beyond the manhandling capabilities of the strongest individual. What if it won’t float? I fretted; the only buoyancy in the kayak was the space between packed items, sealed by the watertight bulkheads fore and aft, and there was precious little of that.

At the edge of the incoming tide on the ripple-ridden Mersehead Sands, I jammed a final four waterproofed packages – along with an old ammunition canister used to hold my camera tightly between my legs – pulled the spray cover over the cockpit coaming and tried not to think of what would happen in the event of a capsize. Would it roll? Could I free my legs in time to get out?

In stark contrast to the sunny Glasgow press launch, the real journey began, as it was most likely to continue, alone beneath an overcast sky. Pippa had gone, unable at the last moment to watch me paddle away from her. To my left the disused, unpainted lighthouse at Southerness – one of the oldest in Scotland and built in 1748 to aid sea trade with Ireland and the New World – was my sole onlooker; it felt strangely appropriate.

The Solway at low water is a vast expanse of mudflats and quicksands across which it is possible, with local knowledge, to walk or ride from England to Scotland. But the incoming tides, known as the ‘White Steeds of Solway,’ are rapid and fierce, reaching speeds of 8 knots, and can be heard approaching by shore dwellers twenty miles distant. The race is fast enough to overtake a galloping horse, and many were the travellers drowned in the ‘Sulwath’ on a mistimed return from the Cumberland fairs.

Within minutes of sealing the cockpit there was water all around me. Small waves parted across the kayak’s bow and sped shoreward; but the boat sat unmoved, only sinking lower into the softening Solway sand.

Now the waves were lapping over the foredeck, and still there was no response from the heavy boat. This was worrying; if it was to carry me across 1,800 miles it would be reassuring to feel it float! One of the publicity stickers, ‘S.S.S.: Sub Sea Services,’ winked at me wickedly.

I pushed downward with both hands but met nothing solid, leant heavily on the paddle and tried to punt forward; a creak from the fibreglass but no movement. Thinking of the Solway horsemen I began to sweat beneath thermal layers. Oozing mud had already engulfed half the kayak and held it fast while the waves grew, breaking now in my lap. I knew I had to struggle free soon or abandon the boat and wade for shore, so I gripped with my knees and started the sideways rocking motion of a bored child. At last, a movement! With a slurp, the sand and mud released their grip. Just as the kayak began to rock freely, one big wave crashed hard on my chest and the kayak bow surged upward in response. I twisted round and pushed with the paddle to free the stern as the wave passed beneath. And then we were afloat. The inertia of the loaded boat was appalling and I felt the bottom bump sand twice more, but there were four months of determined training behind each solid paddle stroke and nothing was going to hold me now. Never had the kayak felt so heavy; never had it sat so low in the water – but, my God, it floated! And what’s more, I was making progress: already beyond the wave-break line and heading west; my journey had begun.

The steady rhythm of paddling, the gentle dripping of water as each blade lifted clear of the sea, the co-ordinated, economical use of the whole body to push the simple craft through the waves, the unusual qualities of light for which the Solway is famous, all helped to erase, for the moment, any worries I had about the overloaded boat.

Clocking miles westward along this coastline of smugglers’ caves and low cliffs was what I had yearned for; months of planning and preparation, the stress of publicity, the sweat of intensive training and the obligations of sponsorship disappeared behind me. I was alone, the sea was mine, and ahead … well, who could tell?

On the first full day I rose at 5.45 a.m. to catch the weather forecast and the best of the tide. Wind dropping, skies brightening and a full Solway tide in my favour, it looked like a good day for progress. I reckoned on an average paddling speed of 4 knots (which may not seem much, but a steady 3 knots would carry you round the world in a year) and, with six hours of tide assistance, a daily distance of twenty-five to thirty miles. However, this estimate was unreasonably proposed under the crazy assumption of meeting ‘average’ weather and wind conditions, and seconded in the light of a good sleep and an early start. With a few days’ experience of the local weather pattern I became accustomed to scaling down those estimates considerably; but it was a pattern ‘local’ not so much to Galloway as to ME and was to remain with me for most of the four-month trip.

There was much to learn about managing this world of tides to best advantage. You can’t efficiently paddle against a strong tidal stream, so that these great longshore movements largely dictated the times and rates of travel. Times of high and low water also played a major part in the cosmic equation, and often I learnt the hard way. Hauled out on a rough shore for lunch, I beached the kayak between dog-sized boulders and went on foot to explore a cave. Half an hour later the rapidly ebbing tide had left the boat stranded ten metres from the water’s edge. It took me over an hour to haul and drag it – and not without damage – across the large boulders which were steadily being uncovered by the retreating tide.

Afternoon progress too was halted. This time by the red flag of a tank and artillery testing range which, for two hours at a time, renders Mullock Bay an unpleasant place to be in a small boat. Rather than defy the flag, I hauled ashore and wandered up to the look-out tower, hoping for a cup of tea. The ‘look-out’ jerked to attention as I entered, but soon dozed off again once he realised that I was not a superior officer. Regular shell blasts shook the tower on its wooden stilts, but the sun streamed in through the open window and very soon I too was nodding off. By the 4 p.m. cease-fire, the last thing I felt like was taking to the water again and paddling the remaining ten miles to Kirkcudbright, but I had to get beyond the firing range while the flags were down.

The best of the day’s weather had now been replaced by a strengthening wind, all along the rough coastline the sea had developed an irregular angry-looking ‘chop’. I splashed my face with water, slipped into the kayak, and launched with a push from the rocks. Immediately, I was sprayed with the shredded spume of waves which broke on the deck. Riled, I stepped up the pace, putting an extra push behind every stroke and leaning aggressively into the headwind, but my drowsy afternoon had left me short of energy and I was tiring fast. By the time I reached Gypsy Point the sea was dangerous and difficult with a Force 7 wind opposing a 3-knot tide and the MOD, concerned about deteriorating conditions, sent the Range Safety Launch out from Ross Bay to check on my progress.

I watched the powerful launch heave its bulk towards me through the churning sea and wished I could free my hands to photograph it – but they were fully occupied wielding the paddle to steady the random bucking of the kayak, whose previous inertia meant little to that breaking sea. All I could manage was a wave of reassurance and ‘Thanks’ before rounding Gypsy Point and gaining the more sheltered conditions of Kirkcudbright Bay. It was 8 p.m., and the four-hour strain of Gypsy had left me positively knackered. Cold and tired, by the time I’d crossed the bay all I wanted was to pitch tent, eat and sleep. But with dehydrated rations, before I could eat I had to find water. I thought I had hit the jackpot by camping near a small public-toilet block, but found it securely locked. High in the wall a small window was open, so I shinned up a drainpipe and squeezed my tired limbs through the tiny space, dropping head-first to the floor below. I washed the salt from my face and filled my water container in luxury from the chrome tap, but it was a further half-hour before I could summon the strength to climb back out! ‘Just’ add water, indeed!

Once I had rustled up a meal, changed into dry clothes and pitched the tent, I was more than ready just to flake out and sleep until morning brought a new tide and the need to face the sea again. But according to the regime of expedition flexi-time this was ‘administrator’s hour’; forward plans had to be made, maps studied, tidal movements calculated and the daily log written before the events of the day drifted off on the ebbing tide of consciousness.

Relaxed and dry, this was also the time for reflection, problem-solving, and assessing the chances of the expedition. I had underestimated the almost miraculous ability of salt water to penetrate supposedly watertight packing and, despite wrapping it in bags, bin liners and cases, much of my gear had become sodden in the rough passage off Gypsy Point. ‘Must be more careful!’ reads my log after I discovered that my vital West Coast Pilot book had got damp. I relayed a message of my position and tomorrow’s plan by radio, via a passing fishing boat, to Ramsay coastguard on the Isle of Man. I carried a Marconi CoastStar hand-held radio in a waterproof case, but the case had developed a crack and the radio too would have to be carefully stowed in poly bags within the hatches of the kayak. This wasn’t an ideal solution, since it would take up valuable space and be unreachable from the cockpit.

‘Have I done too much today?’ was the next log entry. I had covered only perhaps twenty miles in a long day, but had pushed myself hard in heavy seas for four of those hours in a wind stronger than I’d ever paddled in before.

I made a mental note to take it easier tomorrow, but the seeds of doubt, once sown, sprout quickly.

Could I continue with long, hard days followed by lonely nights for a four-month period, without home and comfort, without Pip? Solo canoeing was as yet new and strange to me. There was no one to discuss the fear, the exhaustion, with, no one to share the planning decisions, no one to relax and forget with and no one else to blame when it went wrong. Apart from football, I had never met a physical challenge that I hadn’t, with effort, been able to transcend, but this was another story, a genuine unknown. Among other things it would become a journey into ME, and I wasn’t at all sure I wanted to go there! For the first time the scale of what I had undertaken began to dawn on me – almost 2,000 miles of dangerous sea and a real possibility of drowning – but how could I back out now? With publicity, sponsorship and the charity involvement, to abandon the trip would require a damn good excuse. For a brief moment I considered smashing the canoe irreparably or injuring myself, and wished I hadn’t started at all: I felt helpless, trapped and entirely to blame. This spirit of mutiny was to surface occasionally throughout the trip as a dissenting faction within a basically contented, often euphoric expedition soul. But already I had the germ of the ability to cope with it for on the same page of the log is a reminder that I must ‘try to see this attitude as a part of tiredness, weather and a reaction to previous months of tension and stress’. After all I had only been at sea for two days! Nevertheless, I felt very alone.

Waiting for the tide to turn, I hitched a lift into Kirkcudbright where, flicking idly through the paper, I was stunned by the main picture on page 3. Not what you’d expect, perhaps, from the reputable local weekly, but the picture was in fact of Yours Truly! The publicity machine was working its way ahead of me. Time to move on, I thought, as I jogged back to the bay ready for a good day’s paddling. A Force 6 wind was forecast and it looked like being another day of limited mileage. But I was less preoccupied with the weather than with the story of a sea mystery still claiming hot columns in the local press and creating hot gossip in the pubs, for I was about to enter the ‘Manx Triangle’. Only two months earlier the Kirkcudbright boat Mhairi L, fishing for scallops in calm conditions and in familiar waters near the Isle of Man, had sunk with the loss of five lives. It was a tragedy which had stunned the community, for no ordinary explanation seemed to account adequately for the boat’s disappearance; lack of any radio communication or distress flares suggested that she went down very suddenly and without warning – a strange occurrence under fair conditions.

The talk in the pubs, where the boat and its men were known, was that she must have been pulled under by something very large moving very fast, and in Whitehall there were allegations that the American nuclear-powered submarine – the USS Nathanael Greene – was responsible. It had been seen returning to its Holyloch base under cover of darkness, damaged (missing one propeller), and it was alleged that its crew had been immediately sent back to USA.

The Ministry of Defence, however, stated that there were no submarines operating on that day and that the Irish Sea was not used for submarine manoeuvres as it was too shallow.

The official explanation was that the Mhairi L must have snagged and been pulled under by an undersea telephone cable serving the Isle of Man. Scallop boats drag an iron dredge along the sea bed to unearth scallops which are then caught in a trailing net, and a video film taken by naval divers showed that that the telephone cable was indeed looped over this dredge.

However, local unrest and continued speculation seemed justified, for the official explanation was far from watertight. British Telecom at first denied that there were any cables in that area, although they later changed their story. Local people who saw the naval video claim that the cable seemed far too tightly tangled in the nets of the boat, and the Navy can hardly be counted a disinterested party in the inquiry. Furthermore, it is hard to understand how local men, trawling in a known area, could snag on a chart-indicated cable and, even then, how the cable could pull the boat under so suddenly and without warning.

But perhaps the most sinister aspect of all was that the wreck of the Mhairi L