18,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Hamad Bin Khalifa University Press

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

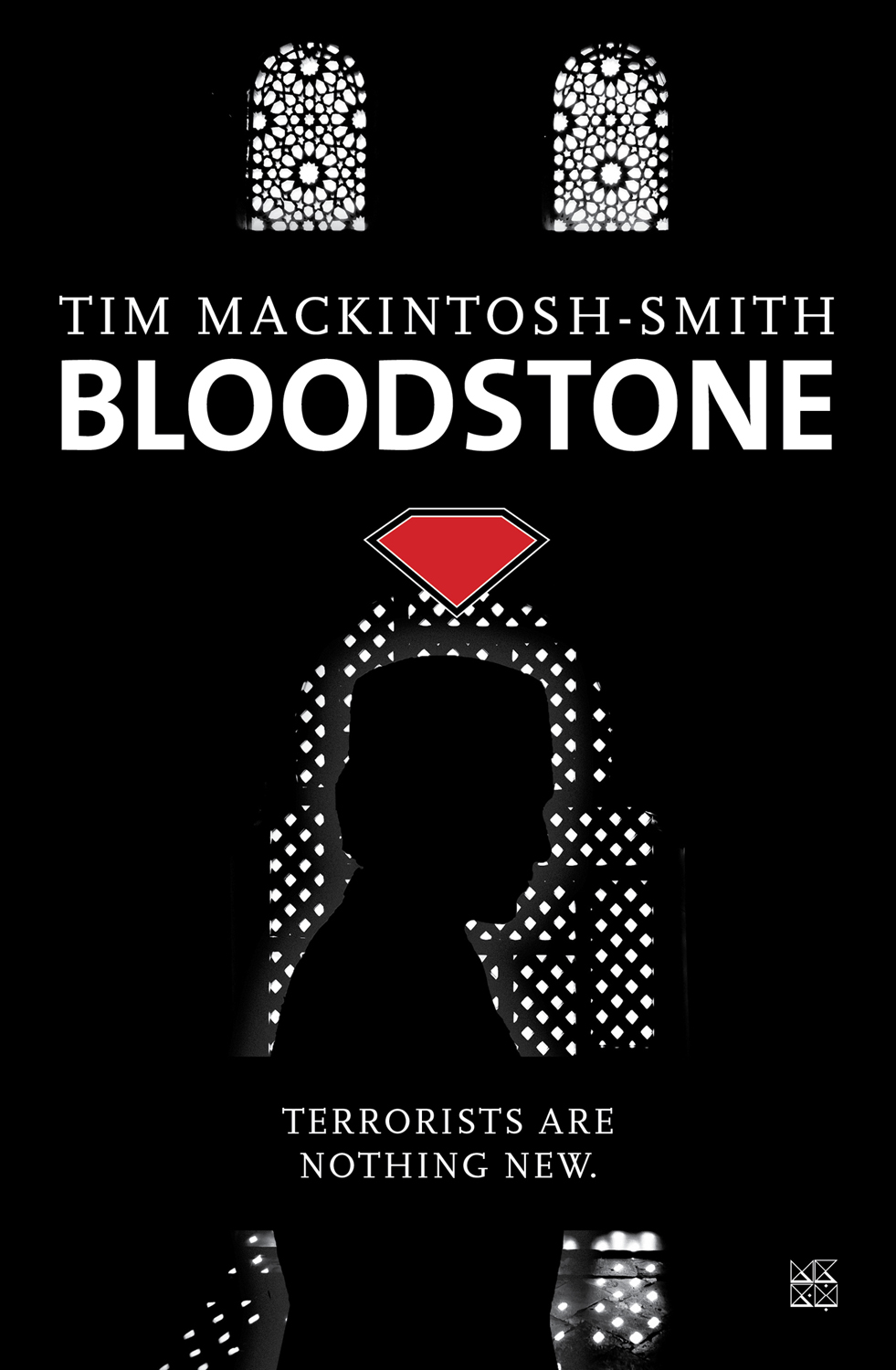

1368: Granada is under threat from violent extremists. Abu Abdallah, the penniless globetrotter and his West African slave, Sinan, arrive to find the labyrinthine palace-citadel, the Alhambra, nearing its triumphant completion. Inexplicable events and baffling mysteries lie in wait at every turn and threaten to ruin forever the delicate balance of Muslim- Christian power in Spain.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2020

Ähnliche

BLOODSTONE

Hamad bin Khalifa University PressP O Box 5825Doha, Qatar

books.hbkupress.com

Copyright © Tim Mackintosh-Smith, 2017All rights reserved.

No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publishers.

No responsibility for loss caused to any individual or organization acting on or refraining from action as a result of the material in this publication can be accepted by HBKU Press or the author.

TPB: 9789927118562

eBook: 9789927118579

Typeset by York Publishing Solutions Pvt. Ltd., Noida, IndiaPrinted and bound in Doha, Qatar byAl Jazeera Printing Press Co. L.L.C.

To find out more about our authors and books, visitbooks.hbkupress.comfor extracts, author interviews, upcoming events,and to sign up for our newsletter.

Qatar National Library Cataloging-in-Publication (CIP)

Mackintosh-Smith, Tim, author.

Bloodstone / Tim Mackintosh-Smith. - Doha : Hamad Bin Khalifa University Press, 2017.

Pages ; cm

ISBN : 978-9927-118-55-5

1. Terrorists - Fiction. II Title.

PR6061.A724 B56 2017

823.914 - dc 23

For Abdulwahhab, Ashwaq, Shayma’, Muhammad, Shadha, Ruqayyah, Ghayda’ and Umm Muhammad who heard this story first

Contents

Main Characters

ix

Prologue

xi

Chapter 1

1

Chapter 2

7

Chapter 3

11

Chapter 4

23

Chapter 5

27

Chapter 6

33

Chapter 7

41

Chapter 8

45

Chapter 9

59

Chapter 10

65

Chapter 11

73

Chapter 12

83

Chapter 13

91

Chapter 14

99

Chapter 15

111

Chapter 16

117

Chapter 17

137

Chapter 18

143

Chapter 19

151

Chapter 20

157

Chapter 21

163

Chapter 22

167

Chapter 23

177

Chapter 24

185

Chapter 25

191

Chapter 26

193

Chapter 27

199

Chapter 28

205

Chapter 29

213

Chapter 30

223

Chapter 31

231

Chapter 32

239

Chapter 33

247

Chapter 34

253

Appendix: Arabic and Spanish Place-names

269

Afterword

271

Main Characters

The Travellers

Sinan, slave of Abu Abdallah

Abu Abdallah Ibn Battutah of Tangier, former judge and globetrotter

In Seville

‘El Bermejo’, properly Muhammad son of Isma’il, Sultan Muhammad VI of Granada (by usurpation)

Don Pedro, King of Castile, known as ‘the Cruel’ or ‘the Just’

Abraham Ibn Zarzar, physician and confidant of Don Pedro

Solomon of Seville, dealer in gemstones

Cristóbal the Moor, goldsmith of Seville

In Granada

Lisan al-Din Ibn al-Khatib, Grand Vizier of Granada

Ali the Alchemist, scientist and libertine

Lubna, qaynah (female singing slave) and concubine of Ali the Alchemist

Sergeant Hamid of the Mamluk guard

Ibn Zamrak, Sultanic Secretary to the Sultan of Granada

Zayd, Clerk of Works in the Alhambra

Umm Ahmad, a decayed old woman

The Chief of the Night, head of the Granada constabulary

Sultan Muhammad son of Yusuf, Sultan Muhammad V of Granada

The Lions

Layth, leader of the Lions (a group of conspirators)

Dirgham

Hattam

Sarim

Haydar

Jassas

Prologue

By the ruins of Itálica, Seville, 29 Jumada ’l-Thani 763 (25 April 1362) He knew he was going to die. Here. Now. The Christian, his killer, was behind him.

He rode on, staring into the shimmering emptiness ahead, counting out his life in heartbeats. The only sounds in the rising morning heat were the creak of harness leathers and the hoof-falls, muffled in dust, of his mount. If it could be called that: a donkey, for a Sultan! He smiled his last smile. At least this cloak of scarlet was a fitting funeral pall for him, for Muhammad son of Isma’il, Sultan of Granada, Commander of the Muslims.

His killer, the young king, called him ‘El Bermejo’– the Red One. Red cloak, red hair, red beard. And in the pouch about his neck was something redder than the rest, redder than the blood that would soon be shed. He felt it, cold and insistent, knocking at his breast.

A question came: who would wash him, pray over him, bury him?

No one. He’d be hacked up, hung up, a warning.

A lark cried falling far and high through the sky above the plain. Then, at last, it came, the hard dry drum of hooves. He turned to face it.

Death hit him in the breastbone at the point of King Pedro’s lance.

There was no pain. Just everything splintering, and the spring sky somersaulting.

Pedro’s face in the blue, ice-blue eyes smiling down. ‘So, No one wins but Allah, eh, Bermejo? Isn’t that the family motto?’ The young king laughed and kicked him in the head.

‘So . . . much . . . ’ he heard a voice say, ‘for Christian . . .chivalry.’ The voice was his own. There was still no pain, but he knew he was going.

‘Oh, and I’ll have this, too,’ Pedro said, still smiling, reaching down to rip the bloody pouch from his neck. ‘Payment. For screwing me up with Aragón.’

He saw Pedro take the stone out of the dripping pouch and turn it round and round against the blue: distillation of crimson, redder than anything in creation. He opened his mouth to tell him it was cursed. He wanted to die with Pedro’s fear in his eyes, not Pedro’s smile. But the words wouldn’t come.

It didn’t matter. Pedro would find out about the Ruby in time. Just as he himself had, and those before him.

Then everything went red and he knew no more, not even when they came and finished him off.

Chapter 1

The Alhambra, Granada, 22 Safar 770 (5 October 1368)

The three men climbed in silence. Looking up, Sinan saw bastions and battlements leaping skyward through the forenoon light. The road rose, and he realized that the towers sprang from a ruddy cliff of wall that seemed to have no end. He thought of the storytellers back home across the Strait, and of their fabled City of Brass. This was no less fabulous: a citadel of iron, bearing down on the brow of the hill like a rusted crown. He wondered what lay inside.

‘Master,’ Sinan whispered at last to the small man by his side, ‘will your friend make you a vizier?’ He looked at the figure lumbering ahead of them, just out of earshot.

‘He’d better,’ Abu Abdallah replied under his breath. ‘By God’s grace, you know as well as I do, Sinan, how bad things are.’ The lines on his gallnut face creased into a frown. ‘Short of stumbling across a crock of Gothic gold, a vizier’s salary is our only hope of ever paying off the debts.’

And, Abu Abdallah thought, peering beadily up at the fortress-palace like a squirrel surveying an unharvested wood, there were the other perks of high office: titles, robes, estates, embassies to far lands . . . social heights his modest Moroccan forebears could never have dreamed of climbing. Abu Abdallah’s name already appeared, grafted on by marriage, in the dynastic family trees of Coromandel and the Maldives. In the old globetrotting days, before his luck deserted him, he had married royal wives, and divorced them; he had played chess with sultans, and beaten them; he had dabbled in the more dangerous games of coup and counter-coup, and kept his head while all around him were losing theirs. A vizierate at Granada– a seat in the Sultan’s ministerial cabinet–wouldn’t just pay off his debts. It would be the resurrection of his career, his life and, almost literally, of his body . . . It had quite slipped his mind, until he’d turned up unannounced the day before and seen the shock on his old friend’s face, that he was, after all, not meant to be here. Or indeed anywhere on earth.

Yes: I will rise again, Abu Abdallah said to himself with a smile. And the image brought to mind one of the other perks of the high life . . . a stream of women flowed across his memory – Greeks, Turks, Mongols, Tamils, Marathas, fair, dusky, cool, musky, slave-concubines of so many remembered beds. Strange, he thought: I was born just across the Strait, in sight of Spain, and I’ve never had a Spanish girl. Everything but.

‘And, master,’ Sinan said, breaking into his reflections, ‘when you do become a vizier, you will remember your promise, won’t you?’

‘What? Oh, that . . . Sinan, who else but you could be my Secret Secretary?’

Who else indeed? Sinan might have been Abu Abdallah’s slave, but it was he who was the real master of the old man’s life; he who had saved that life, back in the bloody chaos of Fez in ’sixty-two . . .

They followed their host round another bend in the road and were confronted by a great gateway. Sinan stared up at it, and a shock ran down his spine.

At first sight it might have been part of the architecture, a decorative cresting on the summit of the gate. But no; they were heads. Human heads. And they were attached not to bodies, but to poles.

Lisan al-Din, Grand Vizier of Granada, looked up at them and cleared his throat. ‘May God Almighty damn this skull,’ he intoned,

‘that Satan’s skill

Inspired with every form of foul skulduggery!

May it inspire within the mouths and minds of men

No mite of mercy, and no mote of memory!’

He folded his arms, resplendent in embroidered sleeves, over a brocade-hung paunch. The words hung heavy in the forenoon air. ‘Though I say so myself, that second couplet in particular is rather good, is it not.’

It was not a question. Abu Abdallah, much smaller and less splendid in his hooded travelling burnous, said nothing. He carried on squinting up at the row of heads. Their long-dead grins added a frivolous note to the severe stonework of the Alhambra’s main gate. One of the heads had fallen askew; it seemed to be cocking a snook at the world of the living.

‘I composed the verses apropos of the head in the middle,’ Lisan al-Din said. ‘The head of . . . El Bermejo.’ Silently, Sinan mouthed the alien syllables: El Bermejo. ‘It’s way past its best, I admit,’ the Grand Vizier continued. ‘Been up there more than six years, pecked by the ravens and tanned by the elements. But it still does the job. Puts the rebels off.’

‘May I ask a question, sir?’

Lisan al-Din turned in surprise at the sound of the words, uttered in beautiful Arabic, as if wondering where they had come from. It was the third member of the group who had spoken. The slave. But slaves didn’t speak . . . The Grand Vizier’s eyes, hooded and shadowed by chronic insomnia, opened wider than they had for a long time.

Sinan took this as a sign of permission. ‘Was he a Christian, sir? I mean, the former owner of the middle head? I can see some traces of a red beard. And his name sounds Spanish: El Bermejo.’

Lisan al-Din studied the slave. Like his master, the young man was still dressed in a traveller’s burnous. If he had noticed anything else about him, it was only the disturbing fact – uncommon, almost unknown, in Granada since the events of fourteen years before – that he was black. Now he saw a face.

He had seen plenty of Blacks during his years of exile in Morocco; must have seen this one, if he was in his friend Abu Abdallah’s household that far back. But he had never actually looked at a Black. What he saw here took him aback: the features were as surprising, as perfect, as beautiful, as the man’s Arabic. Planes of complex darkness, framed by darker beard that softened hard diagonals of cheekbone. Skin cool as jasper, warm as Egyptian velvet. And the eyes – liquid shot with light and dark. The slave might have been half his age, if that; but the eyes seemed to regard him from a distance of time as vast and unknowable as that continent of his across the Strait, beyond the desert. For a moment Lisan al-Din, Grand Vizier of Granada, literary prodigy of the age, was lost.

The call of a guard up on the battlements brought him back. ‘Sharp eyes he’s got, this boy of yours,’ he said to Abu Abdallah.

Abu Abdallah grinned. ‘Sharp eyes, sharp brain. Sharp name, too, ha ha!’

‘My name is Sinan, sir,’ the slave said. ‘Spearhead . . . sorry, sir. You of all people need no explanation.’ Abu Abdallah twinkled and nodded, as one would to a clever son who has said the right thing. ‘But if I’m not mistaken,’ Sinan went on, looking back at the head on the gate, ‘the redness of the beard is unnatural. It is the result of dyeing with henna. Which suggests that, despite his foreign name, its owner was probably a Muslim.’

‘Goodness,’ Lisan al-Din exclaimed. ‘I see what you mean. Amazing perspicacity, especially for a Black. Where did you pick him up?’

‘On a bend in the Niger, past Timbuktu,’ Abu Abdallah said. ‘He was knee-high to a locust at the time, weren’t you Sinan? A hospitality gift, he was, from the viceroy of the Mansa, or Emperor, of Mali.’

‘Only you, my old friend, only you . . . ’ the Grand Vizier said, shaking his heavy head. ‘Most people would have said in the slave market in Fez.’

‘Yes,’ said Abu Abdallah, suddenly solemn. ‘Only me.’

Again, Lisan al-Din was lost for words. In the seven years since he’d last seen him, he’d forgotten the extent of his friend’s magnificent singularity. And has it really been seven years? he asked himself. Abu Abdallah doesn’t look a day older . . . ‘Hmm. Well. In response to Master Sinan’s hypothesis, I can inform him that the . . . thing up on the gate was indeed a Muslim. Or rather, in theory a Muslim, but in deed a worshipper of the devil. I cannot bring myself to utter his real name, so I refer to him by the name the Christians gave him – El Bermejo, the Red One, so called from the inordinate use of henna which you remarked upon, Sinan. You may also be surprised to learn that he was, for a time, the usurping self-styled Sultan of this blessed land.’

‘The Sultan? How . . . how come, sir?’ Sinan said. Abu Abdallah was pleased his slave had asked. He knew the beginning of the story well: he had heard it from Lisan al-Din’s own mouth during the Grand Vizier’s exile in Morocco. But of its ending, no more than rumours had reached that godforsaken Moroccan province where he himself had spent the last years in virtual exile.

‘Oh, the usual reason,’ Lisan al-Din said. ‘Greed. For money. For power. For all the glittering baubles power and money bring.’ The noon prayer call sounded, at first distant from the plain below, then closer, from the walls above. Sinan looked up at the mighty citadel. ‘Yes, Master Sinan. Greed. For titles, robes . . . concubines.’ He glanced at Abu Abdallah, who was fiddling with the tassel of his burnous. ‘Perhaps, above all, greed for a stone: the Great Ruby.’

A question began to form on Sinan’s lips, but the Grand Vizier turned away and led them onward up the road, towards the gate’s dark mouth.

‘When I was serving the Sultan of Delhi as Malikite judge of his capital,’ Abu Abdallah said as they approached the gaping portal, ‘he used to have a whole avenue of corpses, hung, drawn, quartered, halved, filleted, whatever cut you wanted, lining the entrance to his palace. Uggh. They used to spook the horses.’

‘So you have told me,’ Lisan al-Din replied over his shoulder. ‘On several occasions. You have also told me how you nearly became one of those corpses yourself.’ The Grand Vizier smiled one of his rare and gloomy smiles as he pictured Abu Abdallah’s scrawny body dangling in the Indian sun, the grin twinkling even in death . . . His own smile vanished. That image of his friend, dead, had reminded him of the extraordinary question he had to ask. For Abu Abdallah, who had made a career out of wheedling favours, had now, it seemed, wheedled the greatest favour of them all – from Time itself.

But for now the question would have to keep, until they reached somewhere private; somewhere more congenial to the imparting of shocks. And shocks there would be . . . Lisan al-Din glanced warily at his friend; Abu Abdallah grinned back, a skeleton on the loose from his own cupboard. They crossed the shadow-line of the gate, into the dark.

Chapter 2

Across the valley from the Alhambra, the noon call to prayer sounded through the alleyways of al-Bayyazin. Its thin spirals of sound wound into the deepest corners of the hillside suburb. Ali the Alchemist did not hear it. For him, it was a sort of involuntary noise that the city emitted at regular intervals. It had been many years since he had answered that call.

But he heard the knock on his street door. It sounded through his courtyard, waking for a moment the long grey tabby cat that dozed in a patch of autumn sun, and it sounded in the rooms that opened off the yard. In one of these Ali sat hunched over his work, flecked by dusty light from the lattice that looked on to the street and surrounded by cauldrons and braziers, crucibles and mortars, alembics and albarellos. The knock sounded right inside his head. ‘Damn,’ he murmured. ‘Who is it now?’

Then he remembered that he had invited a few old friends to lunch – a lunch he knew would turn into an all-afternoon booze-up. They drank like drains, this lot. How many jars of Malaga wine would they empty this time? And then – damn again! – the coppersmith was due with the new apparatus, after the afternoon prayer. He needed paying. They hadn’t settled on a price, but Ali knew it would be high. ‘It’s a one-off, your honour,’ the man had said, slowly shaking his head. ‘Never made anything like it in my life.’ He certainly hadn’t. Thank God Layth would come tonight with more funds.

Layth. He rolled the name round his mouth, like a shot of arsenic. He loathed Layth, loathed the sight of those green zealot’s eyes, that beard that didn’t look quite real on a face that had stayed too pretty too long. At least he knew Layth loathed him too. And, thank Heaven, he hardly ever came; apart from anything else, that made it all much safer. When he did come, it was always under cover of night. I’ve never seen Layth by daylight, Ali suddenly thought; maybe he’s a ghoul, not a son of Adam. And he would never come further than the lobby. To Layth’s sanctimonious nostrils Ali’s house stank of scandal and of wine, the mother of mortal sins, and he always fled it like a raped nun.

And yet neither could do without the other. Layth needed Ali’s brains. Ali needed Layth’s cash.

He heard loud drinkers’ voices going through the courtyard to the guest room. Oh, they were OK. They were fun. They kept the mental flab of middle age in trim . . . carefully, he added the last measure of white powder to the liquid in the beaker . . . He’d go and join them, have a bite and a few cups – not too many, not with the work he was doing – then leave his guests in Lubna’s capable hands.

Lubna could cope with anything. They still talked about the sparring match she’d had with the blind poet of al-Mudawwar. He’d tried to grope her, pretending to feel his way, and she’d hit back with words: ‘Filthy old man! But what can you expect from someone brought up in al-Mudawwar with the billy-goats, where they think that piss is perfume and shit is sugar-candy?’

‘What woman’s voice is this?’ the blind man had asked, feigning surprise.

‘The voice of an old hag – like your mother,’ Lubna hit back.

He’d turned his verses on her, but she’d repaid him in kind – and got the better of him. How did it go, Lubna’s famous response?

‘You goad me with your virile rhetoric,

Because I’m of the sex that’s fair and tender.

Beware, blind one, my poems have a prick,

For unlike me they’re masculine in gender!’

Off the top of her head, it was. For a while, all Granada was quoting the brilliant riposte of Ali the Alchemist’s singing-girl.

It was, therefore, no surprise that Ali’s boozing, versifying friends were under Lubna’s spell – and not only the spell of her words. She must have been all of thirty by now; but she had borne Ali no children, and her body was still firm and taut from the girlhood years of herding on the high sierras, before her capture. Her voice, too, still had the rough and sexy edges of her Spanish mother-tongue . . . here it was, calling him now . . . Yes, they were all under Lubna’s spell; yet Ali felt no jealousy. Lubna was his slave, his qaynah, his singing-girl, but the possession was mutual. She was his, in legal terms. He was hers in every other sense of possession, every sense that was meant by love.

She loved him fiercely back, this girl stolen from a mountainside. But the fierceness was shot through with sadness. Sadness that she had given him no children. And the darker sadness that haunted the happiest slave.

‘ . . . Ali! Come at once and deal with this bunch of ne’er-do-wells! Skulking in that stinking den of yours . . . ’ She was almost at the door. At the last moment, he remembered the couscous sieve – the latest in a series that he had ‘borrowed’ from the kitchen and gone on to ruin with his new process – and tried to hide it.

Too late. Lubna stood there, light and dark. Dark from the shadowed doorway; dark eyebrows and dark peak of hairline framing a frown. But the darkness could not veil the light in her face, her voice. Ali drank her in, sight and sound, with a thirst that he knew would never be sated. Lubna. White-as-milk. And that was only the half of her.

She saw him try to hide the sieve and smiled through her frown. Dark lips, bright teeth – Like silver, the song went, at the bottom of a well.

Chapter 3

Inside the gateway there was a clatter of arms as the guards saluted the Grand Vizier and his guest – then a silence, as they eyed the slave. Sinan had already found the looks more penetrating here in Granada than they ever were back in Morocco. There was a barbed edge of hatred to them. He ignored them and looked up at another massive archway, and a half-seen inscription – of welcome, or warning? He couldn’t make it out – and then the gloom swallowed them. They doglegged upwards through the darkness, then emerged into day again, inside the Alhambra.

Into day; but Sinan felt that the light here, within the walls, had a distinct quality, a shade of darkness felt rather than seen. It was almost as if they had come to another country, islanded by the great red walls, with its own sky. And its own population: there were functionaries in embroidered robes and caps, younger and less exalted versions of Lisan al-Din, purposefully shuttling across the forecourt; there was a small knot of religious scholars or judges, distinguished by their nodding turbans, awaiting entrance into some inner sanctum; and, stationed at intervals round the periphery, soldiers whom Sinan knew from their dress and complexions to belong to the sultan’s elite Mamluk guard – mamluks, slaves like himself, but captured in the Christian territories then converted to Islam and a culture of fervent militarism. He could feel several dozen pairs of eyes on him.

One of the functionaries, a scribe with a bronze pencase in his waist sash, came and drew Lisan al-Din aside. ‘You must excuse me,’ the Grand Vizier said to Abu Abdallah after a short whispered exchange. ‘I am summoned. But I will be back shortly to show you round. Not the full tour, I’m afraid, as His Presence the Sultan is in residence. I have some interesting sights to show you, however, which will more than make up for the ones you may not see. Meanwhile, I’ll get someone to take you up the Watchtower. We always start there with our . . . more distinguished visitors.’

Abu Abdallah inclined his head at the compliment. Before leaving them, Lisan al-Din spoke to the scribe, who spoke to a lesser official, who spoke to a Mamluk sergeant with a crooked nose, who spoke to a lesser Mamluk, who marched through another gate. Sinan had the impression of being in some elaborate colony of insects, a pyramid of multiple hierarchies and concentric walls, ever more impenetrable. He wondered if he would ever get to see the man, the Presence, at the centre of everything. He also felt uncomfortable, smothered by stares and by the sheer density of it all.

A few minutes, later his claustrophobia was blown away. An officer led them through the inner gate, across a bridge over a small ravine, along a narrow street that passed between the Mamluks’ barracks, up a wide dark staircase – and on to what Sinan could only think of as the prow of a ship sailing through the sky.

‘Glory to the Creator!’ Abu Abdallah exclaimed, panting from the climb as he looked over the parapet. Above him the red standard of the Nasrids, the dynasty founded, like this tower, by the sultan’s ancestor five generations before, flapped a brisk tattoo in the breeze. Sinan joined his master and tried to take in the view.

To the east the great outer wall of the Alhambra curved round – the hull of the ship – reinforced by the stark square bastions. Immediately beneath this, to the north, wooded green waves of hillside rolled and plunged down to a deep cramped valley. Beyond the valley rose another steep roller of hill, its lower levels covered by a tightly-packed, tumbling flotsam of houses, its treeless crests burnt yellow by a long hot summer. The upper end of the valley was enclosed by more sere peaks and by the serpentine line of the outer city wall. On the near side of the wall, on a steeply terraced slope, Sinan could just make out the regular piles of stones that marked a cemetery.

He turned – and gasped. Before him, to the west and south, beyond a foreground of city punctuated by the exclamation marks of minarets, lay a plain. At first it seemed as vast and as infinitely green as the Encompassing Ocean, but then Sinan saw that it was dotted with farmsteads and mansions and framed by a far shoreline of hills. Further to the south-east, the hills swung in and swelled into jagged mountains, backlit and glowering and even now, in early autumn, streaked with last winter’s snow. He tried to take the view in, and couldn’t: it was too big, too strange. It all had the vivid unreality of a landscape seen in a dream.

‘So what do you think of that, my boy?’ Abu Abdallah said, softly. ‘I said you’d see some fine sights when you took to the road with me.’

Sinan had no answer. They stood there for minutes on end, silenced by the panorama before them; even Abu Abdallah – who, as the cook-slave back home once said, uncharitably, but with some truth, made a noise even when he wasn’t making a sound.

At length Abu Abdallah spoke. ‘He’s a fine fellow, Lisan al-Din. Historian, poet, orator, biographer, calligrapher. You name it, he does it, with style. Lisan al-Din, “the Tongue of Religion” . . . Hah, no one ever remembers my honorific – Shams al-Din, “the Sun of Religion”; but then, we “Suns” are two a penny. Lisan is the one and only, the silver tongue with the golden pen . . . unlike your old master, who was blessed with a tongue like a banana skin and a pen that ties itself in knots. The gift of the gaffe, that’s what I’ve got, Sinan.’ The silence cut in again, but only for a moment. ‘Not that it matters, of course, when one is universally acclaimed as the world’s greatest traveller. But to be a stylist and a statesman like Lisan is something of an achievement too. Although . . . ’Abu Abdallah turned to Sinan and lowered his voice ‘ . . . between you, me and the flagpole, he’s a bit pleased with himself.’

Sinan thought of pots and kettles, and had to look down to hide his smile. ‘But then who wouldn’t be, running this lot?’ He spread his arms to take in the Alhambra, the plain, the mountains. ‘The sultan merely reigns. Lisan al-Din’s the one in charge.’

The breeze suddenly dropped; the red standard of the Nasrid dynasty wilted and fell silent. ‘Master,’ Sinan said, ‘will he really make you a vizier?’

Abu Abdallah drew himself up to his full, diminutive height. ‘Undoubtedly, by the grace of God. And if not Lisan al-Din, then . . . someone else. Sometime soon.’ He looked at the distant hills, his billy-goat beard jutting over the battlements. ‘I may be getting on in years, but one’s as young as one feels. And one’s credentials are impeccable: Malikite Judge of Delhi, Ambassador Plenipotentiary to China on behalf of the Sultan of Hind and Sind, Chief Justice of the Maldivian Archipelago, brother-in-law to the Sultan of Coromandel . . . ’

Sinan’s mind glazed over until the familiar litany was finished. ‘And master, when you do become a vizier, you won’t forget your promise, will you? I mean, to appoint me . . . ’

‘ . . . my Secret Secretary?’ Abu Abdallah said, completing the equally familiar question. ‘Sinan, how many times have I told you? No one else on earth could fill that position.’

The wind rose again. Sinan could see a dark army of clouds appearing over the far rim of hills, the vanguard of storms. For the first time this year, he shivered.

The Mamluk with the crooked nose led them back across the forecourt. Lisan al-Din was waiting for them by a doorway. It was an undistinguished doorway in a discreet façade. But Sinan felt that something momentous lay within.

He followed the Grand Vizier and Abu Abdallah along shadowed passages and through low chambers – in all of which he could sense, rather than see, the eyes of Mamluk guards – until they entered a large room. Its full dimensions were at first invisible in the latticed light. But as his eyes adjusted, Sinan made out the dancing patterns and colours of tile mosaic on the walls, and slender marble columns burgeoning into carved and painted capitals that supported a coffered wooden ceiling, richly inlaid. The ceiling seemed to bear down on them, like the lid of an elaborate jewel-box; or coffin. Sinan thought of those caverns, haunts of thieves and jinn, that he’d heard the storytellers describing back in the market in Fez – dark, glittering, dangerous.

‘The Chamber of Counsel,’ Lisan al-Din said. ‘We must come back when His Presence is sitting in public audience and the shutters are open. In his blessed wisdom he greatly beautified it a few years ago. But much of what you see now was the work of his late father, Sultan Yusuf, of sacred memory, who as you will have heard was murdered while at prayer – ’

‘ – by the hand of a black slave.’ The words came from a shadowed corner, soft, insinuating, enunciated. They were followed by a face – that of a tall thin man in a robe almost as stately as Lisan al-Din’s. The face was angular and pallid; it had a sheen of sweat, or oil. The nostrils flared and twitched, as if scenting decay. The eyes were fixed on Sinan. For the second time, the slave shivered.

‘Yes. Absolutely,’ Lisan al-Din said with deliberate flatness. ‘Allow me to introduce my esteemed colleague Ibn Zamrak, the Sultanic Secretary.’ The newcomer nodded almost imperceptibly. ‘And this is my most honoured friend and guest, Abu Abdallah Ibn Battutah of Tangier, the renowned traveller. No mortal man has seen so much of God’s earth, as you are doubtless aware . . . ’ If the Sultanic Secretary was aware, he showed no sign. So Lisan al-Din continued, reciting his friend’s achievements with quiet but pointed pride: ‘Abu Abdallah devoted thirty years to seeing strange lands, to witnessing the wonders and marvels of creation, to seeking the bounty of sultans and the blessing of saints, from the far west of the Land of the Blacks to the easternmost capes of China. He has trodden both ends of the earth; he has sailed upon the Circumambient Ocean. And few men have suffered so many vicissitudes as he – shipwreck, kidnap, piracy, war, deadly illness, the spells of sorcerers, the wrath of tyrants – and lived to tell the tale. And, for that matter, to write it down. In short, one might say that Abu Abdallah is the embodiment, in our age, of the immort–’ he stopped short; then cleared his throat and continued ‘ – of the immortal Khadir.’

There was a silence. In it, Abu Abdallah, eyes downcast with at least a modicum of modesty, contemplated the compliments; Lisan al-Din contemplated his friend – and his own unintentionally disturbing comparison: al-Khadir, the great traveller of Islamic legend, was one of a handful of humans who had been granted earthly immortality. Abu Abdallah, like al-Khadir, had defied distance. Had he also defied death?

At last, and with evident reluctance, Ibn Zamrak extended a pale and bony hand across the silence. ‘I have indeed heard of you, sir, and of your vicissitudes . . . or should one say, escapades?’ There was no warmth in his words, and even less in his handshake. Nor did he attempt to conceal the small cloth which he drew from his sleeve and with which he carefully wiped his shaken hand; as he did so, Sinan noticed a distinct and unaccountable smell – of vinegar. The Sultanic Secretary then turned to Lisan al-Din and spoke in a low but audible voice. ‘I urge you most strongly to keep an eye on that Clerk of Works. Time is running out. Money has run out – he’s way over budget. In fact, he’s so much over that I can’t think where the excess has gone, except – ’ the voice diminished to a hiss ‘ – into the innermost folds of his capacious sleeves.’ And with that the Sultanic Secretary turned and walked away, throwing another look of undisguised contempt at Sinan.

‘I do apologise,’ Lisan al-Din said when he was out of earshot. ‘Most indelicate of him, talking shop like that . . . But one has to make allowances. Ibn Zamrak’s origins are somewhat humble, and he has a plebeian chip on his brocaded shoulder. Not to mention a lot of ticks in his turban, as they say. Oh, and some very strange obsessions about hygiene. But he also has a point. This palace may look like a piece of paradise on earth, but it is poxed with corruption, riddled with rats – not to mention moles and other forms of vermin. Rotten, in a word. To the very core.’

The Grand Vizier had silenced himself by his own vehemence.

‘When I was Malikite judge of Delhi,’ Abu Abdallah chipped into the silence, ‘I found the best policy was to rise above it all.’

Lisan al-Din did not respond, but continued his own train of thought. ‘That said, even if he does supplement his salary with the odd bit of peculation – and God is the one who knows – Zayd the Clerk of Works is a highly reliable and efficient man. You’ll meet him later. But first . . . come.’ He led them through a small door into a small high-walled courtyard. The long sides were blank; in contrast, the far end was a barely controlled riot of carved and painted inscriptions and geometry and vegetation that framed two further doors. They approached the doors, then stopped. ‘We may go no further,’ the Grand Vizier said. ‘His Presence is within.’

Sinan could feel that presence. He felt it suddenly, in his guts, just as long ago, far away, he had felt the presence of . . . the boliw – the word rose from the deepest chambers of memory, from a tongue he had almost forgotten – the boliw that dwelt beyond the door of a painted house of mud where his father had once taken him. Long ago, far off, in a life beyond reach. What were the boliw? He no longer knew. The meanings and memories of that life had receded like ghosts at dawn; the dawn of another existence. Except for the one sharp terrifying memory that never went away.

‘Wa la ghaliba illa ’llah,’ Abu Abdallah said, reading an endlessly reduplicating inscription in the plasterwork. No one wins but Allah.

‘The motto of our glorious Nasrid dynasty,’ Lisan al-Din said. ‘But now, follow me. I want to show you my . . . new baby.’ For a moment, another of his rare smiles lit the Grand Vizier’s gloomy features.