5,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Muswell Press

- Kategorie: Krimi

- Sprache: Englisch

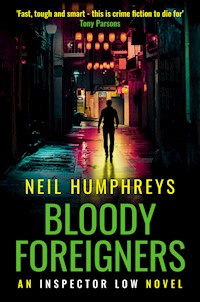

London is angry, divided, and obsessed with foreigners. A murdered Asian and some racist graffiti in Chinatown threaten to trigger the race war that the white supremacists of Make England Great Again have been hoping for. They just need a tipping point. He arrives in the shape of Detective Inspector Stanley Low. Brilliant and bipolar. He hates everyone almost as much as he hates himself. Singapore doesn't want him, and he doesn't want to be in London. There are too many bad memories. Low is plunged into a polarised city, where xenophobia and intolerance feed screaming echo chambers. His desperate race to find a far-right serial killer will lead him to charismatic Neo-Nazi leaders, incendiary radio hosts and Met Police officers who don't appreciate the foreigner's interference. As Low confronts the darkest corners of a racist soul, the Chinese detective is the the wrong face in the wrong place. But he's the right copper for the job. London is about to meet the bloody foreigner who won't walk away. 'This impressive police procedural paints an unflattering but authentic picture of the multiracial megacity.' Mark Sanderson The Times Crime Club.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Ähnliche

iii

BLOODY FOREIGNERS

An Inspector Low novel

Neil Humphreys

CONTENTS

PROLOGUE

Mohamed Kamal knew he was dying. The puddle told him. He was sitting in his own blood. He tried to move, but the pain stopped him. His body was shutting down.

The other voice was no longer shouting. It was quivering. Kamal’s stabbing was deliberate, but his death would be an accident.

The voice turned away from him and faced the ugly black bricks. The wall was built in a different century, a different time, a different London.

Kamal watched his killer take the bloody knife and scrawl four capital letters into the Victorian brickwork.

MEGA.

Kamal knew what the acronym meant.

Make England Great Again.

Written in his blood.

Make England Great Again.

Kamal almost smiled at the irony, but the blood swirled around the back of his mouth and choked him. He was going to be another racist statistic, another opportunity for thoughts and prayers. He’d be a Facebook page, a candle in the park, a poster boy for the oppressed and a puerile chant outside every student union. He didn’t want any of these things. 2

He just wanted to live.

He wanted to see her. One more time. Once would be enough. He knew exactly what he’d say, too.

Thanks and sorry.

That’s it.

Thanks and sorry.

He looked up at the Chinese lanterns. They swayed peacefully in the chilly air. Bloody Chinese lanterns.

Even in death, in London, the Chinese surrounded him. That was too much.

He was not going to die in Chinatown. He was born an Indian man in Singapore. He had lived most of his Singaporean life on Chinese terms. But he was going to die an Indian man, on his terms.

He allowed the blood to dribble down his chin, clearing his throat, giving him a chance to breathe, a chance to drag his broken body through the puddle.

His puddle. His blood.

He didn’t know where he was going, but he wasn’t dying in an alleyway with those words on the wall.

Make England Great Again.

Fuck you.

I’ll write my own obituary.

But his crawling was slow and loud and cumbersome. He pressed his hand against the black dustbin, catching the smell of yesterday’s leftovers, disturbing the rats. He heard scraping footsteps along the narrow path.

‘No, no, no, not out there,’ a voice said.

Kamal felt his hair being pulled back. She had always liked his long hair. In Singapore, he was a rebel with long hair. He tried to think of her, stroking his hair, fooling around, but he couldn’t see anything now.

The pain closed his eyes. He was slipping away, desperate for sleep, waiting for peace. 3

And then he saw the graffiti again.

The anger revived him. Suddenly, his eyes were open. He allowed himself to be dragged deeper into the alleyway’s darkness. He found the energy to turn his head, spitting the blood from his mouth, readying himself for a final act of futile defiance.

His teeth tore into a leg. He bit through the jeans, ignoring the wild, unfocused blows raining down on his head. He reached the flesh and clamped down hard, a rabid dog with lockjaw, no longer in control, no longer caring, oblivious to the punches and the sudden screaming. Blood filled his mouth, but it wasn’t his. He was fighting back, overcome with euphoria. He chewed through hair and skin and tendons, shaking his head to spread the pain, wounding his enemy and cutting him down, following internal orders to take back his dignity. Kamal saw his younger self in the Singaporean jungle, the green-faced national serviceman playing at soldiery. He thought the phoney exercises were pointless then, but the training was sustaining him now, fooling him into thinking that this was a fight he could win.

He suddenly saw himself in uniform, his boots and buttons polished, raising the flag, singing the same, uplifting song of hope.

‘Majulah Singapura’. ‘Onward Singapore’.

He was not going to die at the hands of a racist lunatic in a London alleyway.

‘Majulah Singapura’. ‘Onward Singapore’.

But he didn’t see the knife coming for him a second time.

He just felt it, somewhere in his back, twisting, cracking a rib. Stopping him. Defeating him. Kamal spat out the foreign blood and slumped backwards, lying on his back, staring up at the brick archway. His fight was gone.

But he still had a choice. He could control his death, even in another country, even in Chinatown, beneath those bloody Chinese lanterns.

He could close his eyes and see his father at their roti prata stall, 4tossing the dough in the air, showing off for Arab Street tourists, working sixteen hours a day for his beloved son.

And he could see her beautiful, tender face. One more time.

His last moments belonged to her, the woman he was going to marry, the woman who was going to have their children, the woman who had taken his heart.

And as Mohamed Kamal slipped away from this life, he barely felt the knife being wrenched from his back.

But he heard the words.

‘Fucking foreigners,’ the voice said.

CHAPTER 1

Stanley Low stared at the carpet. An airport’s carpet defined its country. Fourteen hours earlier, he’d left Changi Airport’s carpet. It was new, vibrant, clean and sanitised. The carpet was the work of Asian hands, designed in an Asian country and maintained by migrant labour.

That was Singapore.

The carpet at Heathrow Airport was faded and frayed; once bright and confident, it was now coming away at the edges. Attempts had obviously been made to cover the corners and hide the decay.

This was England.

Huge, garish banners greeted new arrivals. The words of an enthusiastic PR executive were slapped optimistically across Union Jacks.

Britain is Great.

Low considered his own slogan to pass the time.

Britain is History.

His history.

An hour had passed, but the arrivals queue for non-citizens had barely moved. Low watched the Brits swagger through their queue, basking in their inherent superiority, oblivious to the foreigners around them. 6

‘Stay in line, please; have your passports ready.’

The voice was husky and lyrical and belonged in the Jamaican sunshine. The voice was far too cheery and welcoming for 6 a.m. arrivals at a gloomy airport.

He was round-faced and smiley, a foreigner-turned-British citizen who would always be grateful for a steady job and free healthcare. He had a past. So he had perspective.

‘How much longer? Low asked.

‘It will take as long as it takes,’ the plump immigration officer replied.

‘What does that mean?’

‘Excuse me, sir?’

‘It will take as long as it takes. Does that mean an hour, a day, a week? Should I make plans for Christmas?’

The officer stopped. ‘Are you British, sir?’

‘No. Do I look British?’

‘Well, your accent is …’

‘Educated?’

‘No, I just think your English is really good.’

‘Thank you. So is yours.’

The immigration officer paused, as if searching for an explanation for the scruffy, well-spoken Chinese gentleman. Low’s English really was impeccable when it needed to be. But he was tattooed and sweaty. The sight and sound didn’t match.

He was carrying nothing but a passport.

The immigration officer replayed the same thought.

He’s carrying nothing but a passport.

‘Where have you just travelled from, sir?’ the officer asked finally.

‘The toilet. Which was cleaner than this carpet. Maybe you should just let people piss on the carpet and cut the middle man out.’

Chinese faces in the queue turned to face their belligerent countryman. 7

Low saw the minor explosions in his head, the dizzying, wearying fireworks and took a deep breath, waiting for them to fizzle out.

He heard the words of Dr Tracy Lai.

Count to ten and start again.

He watched the immigration officer nod to a colleague, calling for backup.

‘Look, I didn’t mean to be sarcastic, OK? It’s just that we’re all tired, this queue isn’t moving and I need to get to an event in central London.’

Low couldn’t miss the officer heading towards him, a member of the Aviation Policing Command with the semiautomatic across his vest, the Glock 17 hugging his hipbone and the sculpted biceps peeking through the uniform. Low knew the type. Some wanted to serve the community. Some wanted to serve the American movie forever playing in their heads.

‘Is there a problem here, sir?’ The Bulging Bicep enquired.

Low rolled his eyes. The crop-headed clown borrowed his lines from shit movies. The soothing words of Dr Tracy Lai faded. The fireworks sparkled and danced. Low was bored and angry. The Bulging Bicep offered a target, a chance to vent.

‘No, but I have a question. How do you get muscles like that? Do police stations here have gyms?’

The officer tapped his finger against the side of the trigger of his semiautomatic. He couldn’t make sense of the Chinese runt’s aggression. The new arrival was engaging in an argument he obviously couldn’t win. The officer settled on a routine line of questioning.

‘Where are you from, sir?’

‘You know where I’m from. I’m standing with three hundred other people who just arrived on the same plane. From Singapore. You’ve already seen it on my passport. Singapore. And I’ve got a Chinese face. So, let’s consider the facts, shall we? A Chinese guy with a Singaporean passport has just landed on 8a Singapore Airlines flight from Singapore. Clearly, I’m from Zimbabwe.’

The officer considered his options. There were eyes everywhere. Foreign passengers. Returning citizens. Fellow officers. Airport staff. Liberal snowflakes. Everyone had an agenda. Everyone had a camera phone. He was white. The twat was Chinese. He had no choice. Stick to the routine line of questioning. Play the robot.

‘There’s no need for the sarcasm, sir. Where are you staying in the UK?’

‘At the London School of Economics, sir.’

‘You’re a university lecturer,’ the immigration officer exclaimed.

‘Nope.’

‘Then what are you?’ The police officer spat the words at Low, emphasising his indifference to academia.

‘Well, PC Bicep, I am, hold on a second,’ he said, fumbling around in his wallet before producing an identity card, ‘ah, there we are. I am Detective Inspector Stanley Low from the Singapore Police Force. My wonderful government has sent me here to give some really boring lectures on criminology at the London School of Economics.’

The police officer moved his semiautomatic to one side and examined the card. Even his well-drilled line of questioning had deserted him.

‘I didn’t expect that,’ he mumbled, returning the card. ‘You don’t look like …

‘A detective inspector?’ Low interrupted. ‘No, I look like what I am. An arsehole. That’s why I’m here.’

CHAPTER 2

Through the pre-dawn fog, Detective Inspector Mistry noticed the two uniforms giggling. Two white men protecting an Asian corpse in Chinatown in front of all those phones. They were stupid, but not malicious. They were scared. Their bullshit made up for a lack of bravado. That’s why she was in plain clothes and they were in uniform, standing in the drizzle. Besides, she recognised them from the station. They were almost half her age.

‘PC Cook, PC Bishop,’ she said, ducking beneath the police cordon.

‘Yes, Sergeant,’ said Cook, clearing his throat.

‘What’s so funny, lads?’

‘Nothing, Sergeant, just passing the time.’

Cook was the talkative constable, the thicker one. So she glared at the smarter Bishop.

‘No, you’re making jokes to take your mind off the dead bloke behind you. Look where we are. Fruit and veg deliveries are on their way, wholesalers, then office workers and early-morning tourists. Do you wanna go viral?’

‘No, Sergeant,’ Cook replied.

Mistry ignored him, still staring at Bishop, still waiting.

‘No, Sergeant,’ he said finally.

‘Good. No one comes in without clearing it with me first, OK? No one.’ 10

Dansey Place was an alleyway like any other in central London, except it was particularly long, running like a discreet artery through Chinatown, feeding the restaurants on either side. The city’s wealthiest had surrounded the narrow walkway years ago, with the theatres of Shaftesbury Avenue and Leicester Square’s red-carpet premieres a reminder of a world away from fried noodles and chopped garlic.

But Dansey Place’s high brick walls blocked out both the sun and the globalised metropolis. Victorian London still reigned here and some things never changed. Strangers were still being stabbed.

Mistry loved London just before dawn. The night owls had dragged their hangovers back to the suburbs. The office minions had yet to arrive. In the in-between hours, London offered the illusion of peace, the promise of something better.

And then, through the fog, it spat out another victim.

Mistry pulled her latex gloves tighter and smiled at a tall, slim man in a dark suit crouching over the body.

‘So?’

Detective Constable Tom Devonshire didn’t look up. ‘Two stab wounds, both in the back, quite close to each other. The surgeon is on his way. Some grit and shit on his hands, blood along the floor, on his face. He put up a fight and tried to escape, poor bastard.’

Mistry crouched beside the dead man. ‘Grit and shit?’

Devonshire sighed. ‘Yeah, all right. It’s five-thirty in the morning, had to sort Ben out and I haven’t had any coffee yet.’

‘Is he all right?’

‘Yeah, he’s fine. Hasn’t got much choice, has he?’

Mistry moved past the question and focused on the body for the first time. The dead man was young, olive-skinned and remarkably handsome.

Those eyes.

She had seen those eyes too many times before. They always 11captured the moment of revelation, a terrifying acceptance that death was on its way. Those eyes had followed her from one murder scene to another. From a rookie homicide detective in Dagenham to running her own murder investigation team at Charing Cross, the eyes always had it.

They saw the end.

But his brown eyes belonged on a puppy dog, not a corpse. They were beautiful. He was a beautiful boy.

‘Such a waste,’ she murmured.

‘Yeah, good-looking bugger,’ Devonshire agreed. ‘With a face like that, he should’ve been on the stage over the road, not in a gang.’

‘You think he was in gang?’

‘He’s a stabbed teenager with a brown face.’

‘I’ve got a brown face.’

Devonshire didn’t take the bait. ‘You know what I mean.’

Mistry flicked her ponytail away from her shoulder and reached for her torch. ‘Nah, I’m not having it.’

‘Look, don’t get all PC about it. They’re happening every day. We had one yesterday, in your bloody neighbourhood.’

‘That was outside the train station. Revenge attack. This is theatreland. Who killed him? A pensioner pissed off she didn’t meet Benedict Cumberbatch at the stage door?’

Devonshire looked over at his boss. ‘Benedict Cumberbatch is playing in the West End?’

‘Shut up. Teenagers don’t kill each other in the theatre district.’

‘This isn’t really the theatre distrct, is it? It’s Chinatown. And he’s a dead Asian.’

‘He’s Indian. Had an identity card in his wallet.’

‘Meaning he’s Indian?

‘He’s Singaporean.’

‘What the hell’s a Singaporean Indian? And how would you know?’ 12

Mistry stood up. ‘How do you think?’

Devonshire sighed. ‘Ah yeah, of course. Him.’

Mistry ignored the sarcasm and followed the torchlight along the chipped brickwork. ‘He wasn’t stabbed against the wall,’ she said. ‘There’s no blood on the walls.’

‘Of course not. Rival gang members follow him in to the alley, stab, stab and he’s gone.’

The torch stopped moving. The carved letters glowed in the spotlight. Faint blood streaks trailed each letter.

‘Oh shit,’ Mistry muttered. ‘Look at this.’

Devonshire turned and faced the bloodied letters on the wall behind him.

MEGA.

‘Yeah, I know,’ he said. ‘Thought I’d save that for you. Bet you wish it was a gang killing now.’

CHAPTER 3

Charing Cross Police Station didn’t look like one from the outside. The façade fitted its environment rather than the profession. The imposing colonnade was more in keeping with the Roman Empire than coppers on the cobbles. The Agar Street building had once housed a Victorian hospital, a noble attempt to heal the sick in the surrounding slums.

Now the place aimed to provide peace for the dead.

Detective Chief Inspector Charlie Wickes enjoyed working at Charing Cross. He was a middle-aged man of simple pleasures, edging towards a well-deserved pension. He’d worked his way through the ranks at Tottenham, Tower Hamlets and Newham. Different gangs. Different races. Same endgame.

But he came through the other end with a few promotions, a detached house in Chigwell and two teenagers in a private school. He was a proud comprehensive-school kid, but the job had changed his education philosophy.

Stabbing victims didn’t go to private school.

Stabbing victims always looked like Mohamed Kamal.

DCI Wickes sipped his tea and focused on the blown-up images of Kamal’s body on the whiteboard. The dead kid promised to be a real pain in Wickes’s pension. Central London didn’t have the teenage knife-crime stats of 14north and east London, but central London did have the omnipresent threat of terrorism. Radicalised nutcases preferred to kill innocent people around tourist attractions. The footage played better on social media.

Wickes heard their shuffling footsteps. He downed his tea. He was never going to make tee-off time at Hainault now.

‘Morning, everyone. Take a seat,’ Wickes said, as DC Devonshire followed DI Mistry into the office. PC Cook and PC Bishop soon followed. The room filled quickly. Dead bodies didn’t really count, but he was given plenty of resources for one word on a wall.

‘OK, let’s start. Yes, you’ve already noticed that there are a lot of you and I’d like to say it’s because of that poor sod there,’ Wickes said, pointing to Kamal’s broken body on the whiteboard. ‘But we all know it isn’t. It’s because of this bloody thing here.’

Wickes nodded towards a photo of the graffiti found in the alleyway.

‘Make England Great Again. Counterterrorism are jittery about this, obviously. This kid was killed on our patch, so it’s our homicide. But it’s already been made very clear to me that we’re on the clock. No delays. No press leaks and no discussing the bloody graffiti. Ramila?’

Mistry cleared her throat. ‘Well, sir, he had his ID in his pocket, as you know. Luckily for us, Singaporeans carry identity cards with them.’

‘Should have them here,’ a voice in the group muttered.

‘Yes, all right,’ Wickes said. ‘Carry on.’

‘Yes, sir. His name was Mohamed Kamal. He was twenty-two years old, a Singaporean Indian. And he was a Muslim.’

Mistry heard the murmurings.

‘Yes, he was a Muslim. Doesn’t mean he should be dead. He’d completed his national service in Singapore and was a first-year student at King’s College, studying engineering. We’re 15working with the Singaporean authorities to get in touch with next of kin.’

‘Was he rich? Poor?’

‘Don’t know yet, sir.’

‘Well, someone was paying for him to study here. Find out who and why.’

‘We all know why,’ another voice muttered. Others nodded in agreement.

‘No, we don’t know why,’ Mistry snapped. ‘He was just a student, a kid, and now he’s dead. And I’m not sure what his financial status has to do with him being stabbed twice in the back.’

‘Ramila, come on,’ Devonshire said. ‘It’s a reasonable line of inquiry.’

‘It’s DI Mistry and I really don’t think a kid from squeaky-clean Singapore is going to be funded by the fragments of ISIS. And besides, terrorists kill strangers. Strangers don’t kill terrorists.’

Wickes raised his hands. ‘All right, enough. We all know he’s likely to have some sort of income, either here or coming in from Singapore. Find out and speak to them. Now, what about the graffiti? What do we know, Tom?’

Devonshire shrugged. ‘Only the obvious stuff so far: Make England Great Again, a far-right group run by Billy Evans, a nightclub promoter turned Oswald Mosley, supported by mostly white blokes who beat up brown people at weekends. Evans is on a tour of the Midlands at the moment, doing grooming gangs. Again.’

‘What? Pet-grooming gangs?’

Wickes didn’t mind Cook’s puerile joke. Cheeky constables were usually good for paperwork and bad punchlines on murder investigations. Wickes figured he’d need both with the Kamal killing.

‘Look, jokes aside, leave your politics at home. I’m not 16interested. In this room, as far I’m concerned, this is a hate crime and I want this boy’s killer found, all right? Who’s looking at the CCTV?’

‘I am, sir,’ said Bishop, ‘with a fine toothcomb.’

‘Yeah, all right, it’s a dull job. Just get it done with less sarcasm. Rule nothing out at this stage: strangers, residents and—DI Mistry … am I boring you?’

Mistry raised her phone. ‘No, sir. It’s on the radio. They already know.’

Margaret Jones savoured the silence. Just for a moment. Anything more than five seconds and the light flashed on her panel and the producer started banging on the glass partition. Silence was the death of a radio presenter’s career. London Call-In was a talkback radio station. She knew the in-house mantra.

Don’t talk. Don’t come back.

Three seconds was enough. It was time. Time to kill off the snowflake.

‘Well, if you won’t answer the question, Mark, then I will,’ she said, peering up at her co-presenter. ‘But I can’t, can I? Media guidelines deny me the right to speak the truth. Ironically, political correctness means we can only give fake news. Well, OK, let’s see what I can say, shall we? Statistically, in London, the majority of knife crimes are carried out by non-white people, or people who identify themselves as white, you know, when they’re not in therapy sessions apologising again for being white and straight and perhaps even male. Is that OK, for you, Mark? Have I fallen foul of any media guidelines so far?’

Mark Beckett loved and loathed his job with equal measure. He had a voice, an intelligent, smooth, empathetic voice, one polished at the finest public schools, thanks to affluent, bohemian parents who championed social equality, until it came to their son’s education.

But he had a voice nonetheless, a sane voice in the 17never-ending insanity. He saw himself as a counterbalance to the tabloid hysteria, the inflated xenophobia and those self-hating, invisible trolls. He offered an alternative to mainstream monsters like Margaret Jones.

He loathed her and her popularity. He was neither jealous nor insecure. A public-school education always bought confidence and security. He hated what her popularity represented. She was the acceptable mouthpiece of the seething majority, the closet racists who said one thing to the pollsters but ticked something else entirely at the ballot box. She had endorsed and encouraged a poisonous, vicious climate where nothing was off-limits. Every news cycle was open to manipulation and exploitation.

Even a dead Muslim kid was fair game.

Beckett sighed into the microphone.

‘Margaret, I cannot believe you are conflating two entirely different issues here to score points with your unhinged fan base. What has the tragic death of a young man in Chinatown, which may or may not be a hate crime – unlike you, I prefer to wait for official confirmation – got to do with the racial profiles of knife victims on a council estate? You know, as well as I do, that these council estates are among the poorest in Britain, with people of colour predominantly making up the majorities because they are denied the socio-economic opportunities that other British citizens—’

‘Oh for heavens sake, listen to yourself,’ Jones interrupted. ‘Why do they all come here, then? Why are they terrorising innocent families along the northern French coastline while they wait for an opportunity to jump on some poor sod’s truck? Why do they not stay in France? Or Spain? Or Portugal? Why do they come here?’

‘The kid came from Singapore, according to our sources. He came from one of the richest countries in the world. The last time I checked, Singapore hadn’t been a war-torn country since 1942, when the British Empire essentially abandoned the island and left 18them to the Japanese. This kid was probably a student. This kid was probably making a better life for himself, at his own country’s expense, putting money into our faltering education system. And you are surreptitiously playing your Islamophobia card again, to draw attention away from the fact that a political slogan was found beside the poor man, a political slogan that you won’t say on here. Why won’t you say it, Margaret?’

‘Mark, I am not going to play your childish games on the air. You can play to your liberal gallery. I’ll stick with the uncomfortable facts, if it’s all the same to you. The boy’s death is a tragedy, but the government’s failure to tackle both immigration and knife crime—’

‘According to our sources, and a photograph that this radio station has seen, one that we will not be sharing – believe it or not, we do have standards on this show – there was a prominent slogan, the name of a far-right movement, written on the wall near the victim. What did it say, Margaret?’

Jones looked up at the glass partition. Young faces. Different colours. She could see it in their eyes. Innocence. Idealism. Naivety. The hypocritical spoils of growing up in country towns and villages. They wouldn’t help her. She was on her own. The story of her life.

‘We are not going to give publicity to that mob,’ she said.

‘What did it say, Margaret?’

‘We have an immigration crisis in this country, with young people, young men mostly, abusing our longstanding and genuine compassion for war refugees, sneaking into the country on lorries and boats to take advantage of our crumbling welfare system.’

‘What did the slogan say, Margaret?’

Beckett already knew she was beaten. For Margaret Jones’s followers, this killing had the skin colours the wrong way round.

‘Make England Great Again,’ he said, pausing for dramatic effect. 19

‘Make England Great Again. That’s what the slogan said, didn’t it, Margaret? That’s what our sources are telling us. That’s what the photograph showed us. MEGA. Make England Great Again. That really messes with your narrative, doesn’t it, Margaret? You can’t denounce these racists and bigots and white supremacists, can you, Margaret? Not entirely. They make up half your support, don’t they? They watch your TV spots in Russia and all those other bastions of tolerance and diversity. They fund your social media posts. You help their think tanks to dress up the racist rhetoric and make it more palatable for the masses. You share their content on Twitter.’

Jones pointed at Beckett. ‘I’ve never shared anything from that group.’

‘You have retweeted comments, unwittingly or otherwise, from members of Make England Great Again,’ Beckett continued. ‘You have been reluctant to criticise them publicly, either on our radio show or in your newspaper columns, and as far as I’m concerned, in these volatile times, we all have to pick a side. Otherwise, silence is complicity. And now a young Asian boy has died, allegedly beneath the slogan of a repugnant organisation that has been allowed to fester in the open wound that is our polarised society. Anyone who has half-heartedly agreed with the demented ramblings of Make England Great Again and their idiotic members, anyone who has shared, forwarded or endorsed xenophobic posts, videos or funny memes should seriously think about their actions. Are we seriously making England great again? Is this the behaviour of a great country? We’ll take your calls after the break. You’re listening to “Beckett and Jones for Breakfast” on London Call-In. News and sport coming up.’

Beckett sat back in his swivel chair and grinned at his incensed co-presenter. He was going to really enjoy their next few shows.

*

20DCI Wickes wouldn’t close his laptop. He wanted the tinny jingle of London Call-In to drift across the otherwise quiet office. No one spoke. Officers fiddled with their phones, refusing to look up, either at their superior officer or the dead man on the whiteboard.

‘The kid isn’t cold yet,’ Wickes said. ‘Someone around here has a big mouth.’

No one responded. There was nothing to say.

‘So it’s a hate crime. It’s official.’

‘We don’t know that yet, sir,’ DI Mistry piped up.

‘Yes, we do. They just told us. Today it’s on the radio. Tomorrow it’s in the papers. The day after it’s ranting on social media. Next week it’s rioting. I’ll have to liaise with Counterterrorism now. I suspect they’ll take this one away from us. But in the meantime, this is our homicide. DI Mistry, you will run the investigation team. DC Devonshire, you will obviously assist.’

Mistry felt the envious eyes of the white men in the room. They still couldn’t get past her skin colour. As always, she had to say what everyone else was thinking.

‘Excuse me, sir,’ she said. ‘Is this another Asian face to pacify the Asian community? Are you giving me this because my skin tone matches the victim’s?’

‘No, because your skin tone doesn’t match.’

The chief inspector smiled at his old protégé. He still admired that feisty mix of insecurity and arrogance among second-generation immigrants. Their eagerness to prove themselves made them the hardest-working coppers. But their cultural roots made them an asset among ethnic minorities.

Most of the time.

‘The victim was a Singaporean Muslim. You are the daughter of Gujarati immigrants. So, no, Detective Inspector Mistry, I don’t think you match your victim, OK?’

Mistry blushed. Her mentor had always been a kind and 21fair man. He had always been better than this. She needed to be, too.

‘No, sir, but it’s what others will say,’ she whispered, looking around the room.

‘Then they come and see me,’ Wickes said, raising his voice. ‘I haven’t got time for petty office politics. You’re in charge because the victim was Singaporean; that’s the only real lead we have. We’ll need to get in touch with family and friends, and you lived in Singapore. You know the place.’

PC Bishop looked up from his note-taking. ‘You lived in Singapore?’

‘Oh yeah,’ Devonshire said. ‘She was gonna marry one of ’em.’

CHAPTER 4

Stanley Low watched them shuffle into the auditorium, heads down, half asleep. Scrolling. Smartphones. Dumb students. He envied their innocence and hated their youth. Most of all, he was jealous. When he looked at them, he saw himself, in the same building, in a different decade, living a different life.

It was a life he barely remembered, before Tiger, before Ah Lian, before the killing started.

He saw the logo on the lectern, above the door, on the screen behind him and even on the professor’s bloody tie.

LSE. White letters. Red backdrop.

The logo exuded pride. The London School of Economics, for the betterment of society. That’s what it said on the glossy brochure. Low flicked the pages and thought about alternatives.

The London School of Economics, for the betterment of the moneyed class, the keepers of the capitalistic flag and the death of a Singaporean detective.

He knew he was being melodramatic. The school didn’t break him. The place made him. He left London with a first-class degree. He also left behind the best years of his life.

He read the synopsis of the criminology course. His course. The scrawny Chinese student back in 1995 was now a study module. 23

Good luck with that.

Low had given up studying himself. In front of an LSE criminology class, he was a homecoming hero. In front of a mirror, he was unrecognisable.

As the criminology professor stood at the lectern, paying gushing tribute to a man he had never met, Low picked out two words in the course synopsis.

Mental health.

He had found his speech.

His mind was still racing when he heard the applause. He made his way to the stage, shook the hand of a still gushing professor in an ill-fitting suit, and stopped behind the lectern.

An audience of expectant faces waited. Criminology lecturers edged forward on their seats, beaming like proud parents. Low read those words again.

Mental health.

He took a deep breath. The silence screamed back at him. Those fizzing explosions in the brain: he could see the bastard things, leaping in front of him, mocking him.

He found himself in the packed auditorium, a smooth Chinese face, wide-eyed, sitting at the back, away from the spotlight, typically Asian. Low would focus on him, a link to the past and a chance to forget the self-loathing.

‘Mental health,’ Low stammered. ‘Mental health. That’s what it says in your course info here in the brochure. I’m reading the material here. “In your criminology course, you will consider the impact of criminal justice on different social groups, including those differentiated on the basis of their age, gender, socio-economic status, ethnicity, sexuality and mental health.” That’s great.’

Low hesitated, as if debating whether or not to continue.

‘That’s really useful. Let’s talk about that first. I know you want to get to the famous cases, me going undercover for two years in an illegal betting syndicate, me bringing down gang 24leaders, me solving high-profile, sensitive homicide cases that should’ve made me a hero, but instead somehow managed to piss off big business, the Singapore government and the Singapore Police Force itself, which is why I’ve been sent here to give you a motivational talk on criminology, but let’s start with this bit about criminal justice in your syllabus.’

Low nodded towards the red-faced criminology lecturer, who turned away to check the mood of the audience. The tension was palpable.

‘Yeah. Criminal justice. Let’s look at something that has a direct bearing on your coursework, according to your syllabus here, something that will have a practical use in your studies. The impact of criminal justice on different social groups, including those differentiated on the basis of their age …I can help with that, as my guy was quite young …Gender …Well, he was male …Socio-economic status …He was mostly poor, unless a decent match-fixing scam came off …Ethnicity …He was Chinese, which doesn’t really count because that’s the majority race in Singapore. So he had the Chinese equivalent of white privilege, which was rather ironic, as he was eventually murdered by a white man.’

Students gasped. LSE staff fidgeted. Some whispered amongst themselves. The criminology professor started to rise from his seat. Low shook his head.

‘No, no, don’t worry. I’m not here to talk about his murder. It’s that last bit in the syllabus that fascinates me. Consider the impact of criminal justice on mental health. That’s something I think about every day; one particular case study, in fact.

‘About ten years ago now, maybe more, I was tied to a chair in a rundown, empty shophouse in Singapore. I was working undercover. Another kid was tied to a chair beside me. Everyone called him Dragon Boy. He thought he was a gangster. Everyone else thought he was still waiting for puberty. Hence Dragon Boy, the little kid who thought he could. He 25was probably around your age. A teenager. He was an illegal bookie, an ah long, we call it in Singapore, a loan shark. He was nothing, really. We both worked for the syndicate boss, an old Chinese guy called Tiger.’

Excited mutterings spread through the audience. Low nodded.

‘So you’ve obviously read my bio then. Yes. Tiger. Well, Tiger had tied us to a chair because he was convinced there was an informant within his organisation. We weren’t really an organisation. We were a rabble of desperate Chinese men trying to make a living. But the word itself – syndicate – sounds much more impressive in the media, doesn’t it? The Tiger Syndicate. So anyway, he started on Dragon Boy first, slicing his back with a parang. That’s a huge knife, more a sword, really. Dragon Boy screamed, but never said a word. He was a loyal kid. He also wasn’t the informant. I knew he wasn’t. Because I was.’

Low waited for the audience to settle again.

‘As you know, I was an undercover detective. The kid beside me had his back ripped apart because of me. But he never said a word. He protected me. So Tiger started on me.’

Low lifted his shirt and revealed the scars on his torso. As his speech was being filmed, the jagged pink flesh filled the large projector screen behind him. Students covered their mouths in shock.

‘Two things saved my life that day. The first thing was simple logistics. Tiger’s phone rang. There was a big game that night, a football match. He had a financial interest, so he had to leave. Just like that. He slashed two men and left them bleeding in their chairs. Why should he care? That was his job. But the second thing was, he never really believed I was the informant. Never. I was that good at lying. No, I was brilliant at lying. The best.

‘So I sat there, saying nothing, as Tiger dished out his criminal justice on the screaming kid beside me, knowing that he was innocent and I was guilty.

‘But I managed to keep Dragon Boy out of jail. That was my 26criminal justice, my warped sense of loyalty to him. And a few years later, he became my informant. That was his warped sense of loyalty to me, I suppose. He protected me and I protected him. That was our relationship. Our code. But it didn’t matter because a few years ago, he was stabbed to death. He was murdered trying to protect me.

‘And now, thanks to Dragon Boy’s death, and a million other things, my mental health is fucked. That’s my criminal justice. That’s my reward for a lifetime in crime. I can’t sleep at night. I can’t work during the day. And I can’t get fired because of all my wonderful achievements with the Singapore Police Force. So they send me halfway around the world to talk to you lot. And here I am, the unofficial ambassador for fucked-up policemen. Any questions?’

No one raised a hand.

No one clapped.

No one spoke.

No one moved.

Low watched the Chinese student at the back of the auditorium. The kid looked dumbstruck. Low continued to scan the audience, eager to see a face that didn’t belong to the bloodied, screaming Dragon Boy.

And then he found one. She was standing beside the exit.

Low thought he was hallucinating. She couldn’t be there, surely.

The job had taken his soul a long time ago, but the face in the crowd had once stolen his heart.

CHAPTER 5

The George IV pub was the archetypal student pub, tucked away in central London, both chic and shabby. The cast-iron ‘London School of Economics’ name plate, taken from a British Rail train and hung over the bar, reminded every visitor of the pub’s owners. The currency notes stuck to a pillar on the bar, coming from all over the world, underlined the international, affluent clientele and what the school was really all about.

Money.

Low’s father had once sent his gifted son to the same place with the same intentions. A young, intelligent Singaporean prodigy was sent to London but never really returned.

Low took a seat beneath the bright, arched windows and watched her chat with the flirtatious barman. The kid had good skin, a hipster beard and a Eastern European accent, a reliable combination in a student pub. He was also in a safe metropolitan enclave. His accent would be considered exotic and worldly, rather than a threat to jobs and hospital waiting times.

Low figured the kid was where he wanted to be, flirting with an older, well-spoken Indian woman who was both pretty and professional, a classic cougar for a randy, underpaid barman.

That’s what really bothered Low. She was still flawless. Age had actually improved her. Her teenage gawkiness had long 28since given way to confident elegance. The shy Indian girl on the Tube, shying away from the Friday-night revellers, hoping to get from one end of the District Line to the other without being called a Paki had vanished. She was a British-Indian woman, comfortable with the labels on both sides of the hyphen.

Low barely recognised the self-confidence, but her beauty was unmistakable. And it was killing him. And Low only had one way of dealing with pain.

‘So what’s it like being a brown face in Divided Britain, then?’

Detective Inspector Ramila Mistry ignored the belligerence and dumped the drinks on the varnished table.

‘Do you remember this place?’ she asked instead.

‘Vaguely. Victorian pub. Still looks like the Flatiron Building from the outside. Still trying to be a Ye Olde London Pub on the inside. Still got the Hoare and Co. sign out front, one of the oldest businesses in London; still got the same people inside – merchants, bankers, wankers. Nothing changes.’

Mistry sipped her lemonade. ‘Well, you certainly don’t. Still trying to show off your intellect, giving me a potted history of a pub you’ve been in for five minutes. You don’t have to try so hard. I still remember how clever you are.’

Low laughed loud enough to draw the attention of a table of economics students. Low’s eyes told them to mind their business.

‘Oh yeah, I’m a fucking genius,’ he said, still looking at the students. ‘I’m such a genius I get sent back here to inspire the trust-fund babies.’

‘How are things back in Singapore?’

‘Shit. I see you’re married,’ Low said, pointing at Mistry’s wedding ring.

‘Yeah, seven years.’

‘Good for you. Kids?’