Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Muswell Press

- Kategorie: Krimi

- Serie: An Inspector Low Novel

- Sprache: Englisch

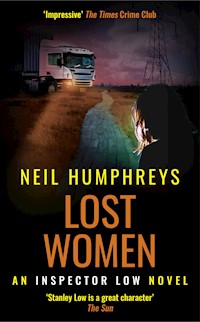

Detective Inspector Stanley Low. Belligerent, bipolar and brilliant. A Chinese-Singaporean, educated in London with a foot in both cities, his mission to eradicate violent crime wherever he finds it. Twelve women are found in the back of a truck, dumped in the Essex marshlands. They all have knives but have nothing to say, except Grace. She will only speak to DI Stanley Low. Brought in to assist with the case Low finds himself dealing with a global trafficking ring and a high-profile billionaire with connections that reach into the darkest corners of power. As one by one his witnesses are killed off, he has no choice but to return to Singapore to examine the darkest corners of the Asian city in his hunt for the traffickers. He must hurry. Another truck is being prepared. Another twelve, vulnerable women are being groomed. Low can only find them if he uncovers the ugliest of truths. The fourth novel in the critically acclaimed Inspector Low series proves that some crimes have no borders, and some detectives won't stop until justice is served.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 399

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

iii

LOST WOMEN

An Inspector Low Novel

Neil Humphreys

For a glossary of popular Singapore terms and Singlish phrases, see p.339

Contents

LOST WOMEN

PROLOGUE

Alan Edwards had expected to see more blood. His initial reaction had surprised him. He’d never seen a murder victim before, let alone one with its throat sliced open. And yet, Edwards remained unexpectedly calm.

Instead, he was struck by the colour. The blood looked black.

He shone his torch through the windscreen. The flies were already hovering outside the lorry. The maggots would soon follow.

Being an ornithology hobbyist of sorts, Edwards was no stranger to nature’s brutality. The wildlife of Rainham Marshes feasted on death. The Thames Estuary kept the swampy grassland attractive for Edwards’ beloved wildfowl and waders.

And the peregrine falcons killed them.

The lorry wasn’t a total shock either. Industrial parks and haulage firms filled the riverbanks recently abandoned by Ford. Gentrification was making its way through East London, but it hadn’t yet reached this part of the River Thames.

Drug dealers and traffickers plugged the gaps in the meantime. Rainham Marshes offered solitude for Edwards’ 2migratory species and privacy for anyone keen on a coke deal. The seasonal birds were temporary. The drug dealers were not. On his pre-dawn treks through the scrub, Edwards had pretended not to see them for years.

But he couldn’t miss a dead Chinese lorry driver.

That was the other thing. Lorry drivers were not Chinese, not around here. They were usually white and nearly always British, especially in recent years, but never Chinese.

And they were never dead.

The long grass danced around the lorry as the cold air filled Edwards’ lungs. For the first time, he realised that he was terrified. He had already called the police, talking gibberish, listing one large, white lorry in a ditch and one dead Chinese driver in the cab like he was ordering a takeaway. And he had followed the firm instructions to wait on the scene; alone, deep inside the Rainham Marshes, with nothing but a torch, a pair of binoculars, a thermos flask and a cheese and pickle sandwich for protection.

Edwards stepped away from the lorry, already making swift, instinctive calculations of his own. The driver hadn’t committed suicide, not like that. He had willingly driven to an isolated spot. The lorry was parked in a ditch, its tyre marks obvious in the boggy terrain. The lorry came in. No other vehicle went out.

Edwards wasn’t alone.

The old man moved quickly. He knew the area well, even in the dark. The familiar woodland was easy to navigate. His bicycle wasn’t far away, just behind the lorry. Soon, he’d be home with his wife, sipping sugary tea and eating custard creams, his hands still shaking as he held the mug and attempted to make light of the slumped driver, the torn flesh and the flies, those damn flies.3

And eventually, he’d return, for his lapwings and little egrets, and he’d forget the man’s open eyes, frozen at the time of death, capturing that moment of realisation.

But Edwards wouldn’t forget. He wouldn’t forget anything, not after she emerged through the long grass and hurried towards him. She was unsteady on her feet, stumbling through the marsh in high heels. Her clothes were all wrong, for the environment and the weather. The hot pants and crop top belonged in a nightclub, not in an Essex swamp before dawn.

The only thing that made sense was the knife. She waved the blade in front of Edwards’ face. Instinctively, the retiree raised his hands.

“Help.”

She was barely speaking.

“Help.”

She was already crying.

Her Chinese face and her foreign accent didn’t belong here ether.

“Help. Please.”

Edwards was already following her back to the lorry. They were running, his terror dissipating, his confusion giving way to something unexpected. Empathy.

“Lai lai. Come.”

“Yes, OK.” Edwards held out his torch to light the way.

She grabbed his elbow, not to intimidate, but for support. She was shaking, tripping through the scrub. Edwards patted her hand.

“It’ll be OK.”

He had no idea what he was saying. But he knew the police were on their way. Fate would take care of the rest.

Edwards heard the banging before they reached the back of the lorry. There was screaming, high-pitched and 4desperate, coming from inside. She was already grabbing the bottom of the roller shutters.

“Open.” She wasn’t strong enough.

“Open.” She was louder now, barking at Edwards.

“Maybe we should wait for the police.”

Edwards thought about his wife, his favourite armchair, the sugary tea and the custard creams. He heard the screaming and hesitated.

“The police will be here any second.”

“Please.”

Later, her mascara-streaked face would stay with Edwards longer than the wide-eyed dead driver. He already knew that the child-like wailing inside that lorry would never leave him.

He grabbed the cold metal with both hands.

Together, they pushed the shutters above their heads.

Edwards struggled to comprehend the chaos that followed. But he remembered a dozen Asian women running towards him.

They all had knives.

Chapter 1

Police Constable Jamie Henderson was already bored. Illegals in lorries were dull. He saw them all the time, snaking their way through the Thames Estuary, mostly alive, occasionally dead, but always a lot of paperwork.

At least the latest lot were pretty.

“I’d give her one.” He nudged his colleague in the ribs.

“Shut up, Jamie,” PC Stuart Walker said, blowing his fingers. His hands were already frozen. He was struggling with his notes and the dithering old man.

“So you were bird-watching, Mr Edwards,” Walker said, leaning into his own car.

He had offered the pensioner a back seat and some warmth. Neither had stopped the shaking.

“So am I,” PC Henderson quipped.

He leered at the girls, still sheltering in the back of the lorry. Until social services arrived, there was nowhere else for a dozen women to wait in the Rainham Marshes. They had dropped their knives. They were in the care of two uniformed officers now. They were safe.

“Especially that one.” Henderson pointed at the woman with the longest legs and the hardest face. She was wearing hot pants and stilettos, the perfect combo. 6

“I’ve always had a thing for high heels.” Henderson’s torch found the woman’s eyes. “I like ’em tall.”

“For god’s sake, Jamie, give it a rest.”

The sun was slowly rising above the boggy swampland, but the air was still chilly. Walker loathed the cold and early morning calls. His mate wasn’t helping.

“Now, Mr Edwards, you called us after you found the driver, but before you found the girls in the back. Is that right?”

“We found the girls in the back.”

Walker was losing patience. “Who’s ‘we’, Mr Edwards? You said you were alone?”

“I was alone. I’ve been coming here alone for years. My wife thinks I’m a sad old git, getting up at 4 o’clock in the morning to look for ‘poxy birds’, as she calls ’em, but I like it. Keeps me fit. It’s better than fishing, especially in this weather.”

Edwards went to sip his tea from his thermos flask, but both men noticed his shaking hands. Edwards changed his mind. “It’s daft, really.”

“What is?”

“To reach sixty-eight years old and never see a dead body—not a murdered one anyway—I suppose you see them all the time.”

“One is too many, sir.”

“Yeah, I reckon you’re right, mate. That’s why I can’t stop bloody shaking. She didn’t shake though, her with the knife. That’s why I thought it was her. She came at me with a knife, running like a bloody maniac through the bushes.”

“Who did?”

“Her over there, the one sitting on the back of the lorry.”

Henderson looked disgusted. “Ah, not her with the high heels?” 7

“Just tell me what happened next,” Walker said, placing a hand on the old man’s shoulder.

“She made me open up the lorry.”

“She made you? She threatened you with her knife?”

“No, no, no, not at all, she begged me. I didn’t really think the knife was for me. It was for her, for all of them, for their protection. They were more bloody terrified than I was. In fact, as soon as I told ’em that the police were coming, they all put down their knives and just sat there, just like that, without a care in the world.”

“OK, thanks, Mr Edwards. Just wait for our colleagues to arrive.”

“Do you think she, you know, killed him?”

Walker smiled sincerely. “It’s unlikely. None of their knives or clothes have any blood on them. A neck wound like that … there’d be blood everywhere.”

“Yeah, I saw it all over the windscreen.”

“It’ll get better, Mr Edwards. Over time.”

Walker’s smile was fake now. He was lying. Both men probably knew that.

The police constable joined his partner behind the lorry. The wind was bitingly cold. Henderson was still eyeing the women, passing the time by giving each one an internal score, a mark out of ten for their imagined performance in his dark fantasies. There was nothing else to do at this time of the morning.

“Any luck?”

“Nah, not a word from any of ’em. Not surprising, is it? They always shit themselves when we turn up. Probably can’t speak proper English anyway.”

“Nor can you,” Walker said, climbing into the lorry.

“Here, what are you doing? You gotta wait for forensics.”

“He’s not dead in here, is he? I’m not disturbing anything in the back of the lorry.” 8

Walker sat beside the woman in the crop top and high heels. “This is the one that ran out to the old man?”

“Yeah, the fit one.”

“So she does speak some English.” Walker smiled at the woman. She wore too much make-up to hide puffy eyes and a lack of sleep. Her coarse features couldn’t entirely hide the fragility. “I wonder why she ran out for help?”

“She was scared.”

“Or she’s the leader. She looks older than the others. It’s worth a try.”

Walker tapped his notepad. She shook her head. The other women didn’t move.

“It’s OK. I’m here to help. Really. I just want to help.”

Walker meant it, too. He was grateful that the women were still alive. He had attended enough manslaughter cases on Essex industrial estates.

He waved his pen in the air. “What is your name?”

Nothing.

“Where are you from?”

Nothing.

“Who sent you here?”

“You’re wasting your time, Stu. They won’t talk to us. Leave it to the translators.”

“Low.”

Her soft voice surprised both men. Walker looked for guidance. Henderson shrugged his shoulders. Neither officer had a clue.

Walker leaned towards her. He had the boyish, kinder face. “What’s Low?”

“I speak to Inspector Low.”

Her English was surprisingly good. But her words made no sense.

“We don’t know an Inspector Low at our station,” 9Walker said, quietly and carefully, not wishing to antagonise her.

“He’s in Singapore.”

“Ah that’s great,” Henderson said. “Our only lead is some geezer in China.”

Chapter 2

Detective Inspector Stanley Low checked his pistol. He didn’t recognise it. The Singapore Police Force had recently replaced his trusty Taurus with a Glock. Apparently, his previous weapon was out-of-date and obsolete.

He knew the feeling.

Low examined the faces hurrying into Parklane Shopping Mall. They were much younger now. They stopped at the escalators and checked their pistols too, mimicking their inspector, following the leader, as always, the Singapore way.

Low checked the deserted mall one more time. This side of Selegie Road was a sweaty, neglected place at the best of times. At 2am, the officers had cooks, street walkers and the odd rat for company.

Only the rats lingered.

The Parklane Shopping Mall was an architectural relic, still trapped in the 1970s. Even the smells belonged to Low’s childhood. Cooking oil and musty carpets filled his senses. Guitar shops, nail salons and TCM outlets catered to those hoping to recreate their past, to look and feel younger, happier. Sexier. 11

The Classic Doll KTV Lounge took care of the lot. Stretched across the third floor, the walls were blacked out, covered entirely by a large, tacky print of a flying horse. Low’s team moved quickly along the print, their shoulders brushing past the wings of the magnificent beast.

“Why they always have a horse ah?” Xavier Ng asked, wide-eyed and jittery.

“Superstition. They think business will be fast, like the horse. Now shut up lah.”

Ng was the latest junior detective assigned to Low in CID. The inspector usually got the kids now. Being a legendary babysitter kept him on the payroll, but out of harm’s way.

“I think it’s time to go in sir,” Xavier Ng said.

“Wait lah.” Low tapped the glass door. “It’s quiet inside. No singing. They’re drinking. You wanna surprise them or not?”

“Yes, sir. You’re right, sir.”

The other sheep bleated in agreement, raising their alien pistols and waiting for further instructions, always waiting for orders.

The sudden blast of Mandopop from inside the KTV lounge made them all jump, including Low. A male voice warbled tunelessly on the other side of the door.

“OK, good, they’re either singing or shagging. Remember, we’ve got our guns out. They’ve got their cocks out. No need to shoot anyone, OK? Right. Go.”

Low kicked the door open and crouched along the long, dark corridor. The smell of overpriced booze and stale sex filled the air. Low’s team moved swiftly towards the violin strings of a weepy Mandarin ballad, just a little further ahead, on the other side of a locked door. His boot took care of the bolt. The butt of his unfamiliar gun took out the overweight Chinese minder. 12

The sound of a large man’s nose breaking and the sight of half a dozen armed detectives triggered the screaming. Skinny, semi-naked women reached for their clothes. Fat, semi-naked men concealed their erections. The small, dank room was filled with sofas, bottles of cognac, used condoms and aroused men and women running around a table in search of their underwear.

On the huge TV, a young couple expressed their love for each other from the top of a Chinese mountain as the lyrics scrolled across the bottom of the screen. The surround sound speaker system amplified that deep love, filling the room with soaring vocals.

“Wah lau, somebody off the bloody TV.”

Low’s orders were drowned out by the teary-eyed singers on screen so he pulled the plug himself.

“Eh, who switch off my KTV?”

A large, angry Chinese man ambled into the room. His stomach appeared to spill over in several different directions, covering the waistband of his shorts. He took a moment to digest the chaotic scene of men and women being handcuffed and turned on his slippers.

“No, no, no, brother, you stay.”

Low hurdled the table, narrowly missing two Chinese women shouting at his junior colleagues and grabbed the fleeing man by the back of the neck.

“Don’t leave your own party, Ah Meng.”

Ah Meng made the mistake of taking a slow, lazy swing at his captor. Low ducked and decided a controlled head-butt would bring an end to Ah Meng’s resistance.

Ah Meng wiped the blood from his nostrils and swiftly agreed.

“Eh, sorry, ah, Inspector Low, I didn’t know it was you.”

“Didn’t know it was me? Balls to you.” Low shoved the 13heavier man onto a crowded sofa. “You always get chee ko pek look like me, is it?”

“You do have one of those faces.”

“Shut up, lah.”

Low was tired. Raiding KTV lounges was beneath him. He was catching nothing but headlines. He watched the others eagerly handcuff sex workers, punters and pimps, almost impossible to distinguish one from the other. They would all be faceless in the next morning’s media photos, deliberately pixelated, supposedly for their protection. But the altered images were for Singapore’s protection. Low knew that. These people had to stay invisible to maintain the illusion that they didn’t exist. Low and his team were the pied pipers of pointlessness. Catch a few. Release a few. It didn’t matter, as long as there were arrests, headlines and photos with no faces.

“You never bother me last time.” Ah Meng wriggled forward on the torn sofa, pushing a sex worker to one side. “Last time you never disturb.”

“Last time you never got greedy.”

“I not greedy, wha’.”

“No lah, Ah Meng. You kept the doors open, right or not?” Low pointed at the sex workers, pulling up their knickers. “You kept them shagging. Forgot about the social distancing last time. You were supposed to close your property, Ah Meng, remember? Property owners who allow their premises to be used for vice-related activities can face a jail term of up to five years or fines of up to $100,000. Remember that one, ah? Those who knowingly allow their premises to be used for vice-related activities will be prosecuted under the Women’s Charter. Repeat offenders can kena fine $150,000, jailed seven years some more. Remember that one, ah?” 14

Ah Meng’s arms flapped in their air. “I’m not the property owner, lease only.”

“Right, well, those who live off earnings from prostitutes can face a jail term of up to seven years …”

“And get a $100,000 fine, lah. You were funnier when you were a fake gangster.”

“Balls to you. Eh, how come you change the picture outside? Now got a galloping horse. Last time you had a flying dragon, right?”

“Dragon lousy for business,” Ah Meng grumbled. “Had to change lah.”

“So the horse is better for business?”

“Where got better? You bastards are here.”

Low only realised he was giggling with Ah Meng when he caught the rest of his team staring at him. They knew his past. They didn’t know how much he still missed it.

The inspector and the brothel owner only stopped laughing when they heard the crying next door.

Chapter 3

Low realised his mistake immediately. Rookie mistake. The kind of blunder he’d expect from new recruits like the doe-eyed Xavier Ng, but not from himself. Never himself. He’d castigate himself later for such a gross error of judgement, another chance to self-flagellate and feed that internal loathing, but not now.

Now he needed to recover. Make amends. Follow the fireworks.

His mind always overcompensated in such moments. The self-hatred fuelled the anger. The anger triggered the fireworks, the explosions of coherence that made the internal shit just about worthwhile.

The crying came from the room next door. There hadn’t been a room next door. During previous raids, the KTV lounge had one ugly main room, with microphones for the singers and hidden cameras for potential blackmailers later. But there was no additional room with an adjoining door.

Low was already pointing his gun at Ah Meng. “You built a secret room after the pandemic.”

“What? No lah.” Ah Meng looked for help around the room. None was coming.

Low tapped Ah Meng’s forehead with his gun barrel. 16“Bullshit. You bastards didn’t play fair, not during the pandemic. Everyone else did, but you kept opening for shagging sessions. After that, no one liked you anymore. Everyone fed up already. No more closing one eye to KTV pimps like you. No more tolerance, right or not?”

“Talk cock, lah, Low.”

Low waved the gun in front of Ah Meng’s face. “You put in secret rooms that the public cannot find, for your special customers and their extra-special service.”

“I never.”

“Give me the key or I’ll shoot you in the balls,” Low said wearily.

Ah Meng did as he was told. Low instructed everyone else to stay put. He didn’t need backup. He had two clear advantages. A gun. And focus. The guy in the next room had neither. Low moved quickly, picking up two faint voices. One distinct, in control, the other distant, in pain.

“You like it, right?”

“Please.

“Stop crying lah.”

“Please. Don’t.”

Her tone destroyed Low. She wasn’t asking or even pleading. She was resigned to her fate.

The inspector didn’t bother with the key. Bullets were quicker. The naked man made the mistake of rolling off the sofa and jumping to his feet. He had a tattooed web on the left side of his neck, stretching across the jugular. He was facing Low, but still off-balance, confused and uncertain, presenting the inspector with an obvious and prominent target.

Low couldn’t miss.

The naked man dropped to the floor, squealing in agony. “She let me do it. She let me do it.”

A second kick was necessary. 17

“I don’t cheat her, OK. I always pay.”

A third kick broke whatever remained of the naked man’s defiance.

“Yeah, OK, OK, don’t kick me anymore.”

“Then say sorry.”

“What?”

“Say sorry.”

“Sorry, lah, officer.”

Low stood over the crumpled heap on the floor, lying in the foetal position, clutching his testicles. The inspector’s shoe prodded the groaning’s man thigh. “Not to me. To her.”

“But I paid her, wha’?”

A fourth kick changed the naked man’s perspective.

“Sorry lah, wah lau, don’t kick me again, basket.”

Xavier Ng arrived in the doorway, respectfully keeping his distance. “Shall I take him outside, sir?”

“Yeah. And don’t let the fucker get dressed.”

Ng dragged the whining man away. Low gently pushed the door towards the splintered frame. He picked up the woman’s clothes and handed them over, his back turned, avoiding eye contact.

“Here. The aircon outside is damn cold.”

She turned away and dressed in silence. Low examined the empty bottles on a cheap, IKEA table. The curled $2 bills. The upturned mirror. The powder. The residue. He heard the groan, too, a spontaneous, unwanted confirmation of pain. “We can take you to a doctor,” he whispered.

“Don’t want.”

“That arm looks painful. You should see someone.”

“No need.”

“He’s too violent.”

She pulled on a T-shirt. “My pimp.” 18

“So he can be violent?”

“He can send me back. So you, ah, cannot …”

“Press charges,” Low interrupted, rubbing the stubble on his cheek. “Yeah, OK. So how?”

She tied her hair into a ponytail. “Like that lor.”

“Yeah. Like that lor,” Low muttered.

He turned to face her. She looked even younger fully clothed, too young for this life and too pretty to be allowed to escape it. He managed a weak smile and thought about his team outside, making arrests and collecting statements. They still believed that their work counted for something.

She reached down for her high heels. “They look uncomfortable,” the inspector said.

“Make me tall. He like tall ones.”

“What’s his name?”

She scowled at his naivety.

“Yeah, all right,” Low said, feeling sheepish. “What’s your name?”

“Janice.”

“Real name?”

“Today, it’s Janice.”

“And tomorrow it’s whatever you need it to be.”

“Yah.” She tightened the buckles on her high heels.

“Surname?”

“Janice good enough.”

“OK, Janice Good Enough. Take care ah.”

She left without bothering to reply. She was a foreign woman in Singapore. She had no status. The inspector couldn’t guarantee her safety and there was little to gain in either of them pretending otherwise.

Low sat on the edge of the massage table and listened to Janice slam a door outside. He still didn’t know how to speak to women.

Chapter 4

Detective Inspector Ramila Mistry hated speaking to women’s groups. She struggled with the tokenism. She was successful. She was attractive. She was British-Indian. She was a high-profile officer in London’s Metropolitan Police Force. But some audiences recoiled at her impressive resumé. She didn’t fit their ingrained expectations. In public settings she was either admired or alienated. On this occasion, it could go either way.

Mistry waited for them to take their seats: mostly white, nearly always middle-class, those with the time and affluence to champion the causes of the downtrodden. She was the daughter of Gujarati immigrants and raised in a Dagenham corner shop, selling cigarettes to angry teenagers in the vague hope that she might not be called a ‘paki’ that day. She didn’t have time between homework and helping in the family shop to read The Female Eunuch.

But she empathised with the fury. That was shared ground for speaker and listener. These women knew that they couldn’t walk home safely after dark. Growing up, Mistry just couldn’t walk home safely.

She sipped the cold tea from a polystyrene cup and waited for the red-faced latecomers to settle. The paper plate filled 20with cheap biscuits only underlined the sad, feebleness of it all. They were armed with a half-empty community hall in East London, dreadful tea and dark chocolate digestives to take on the shit outside. They didn’t stand a chance. Mistry could only play pretend.

“I am a copper. Please don’t hold that against me,” she began, pausing for the polite laughter.

“But I am also a woman. When I’m walking home alone, this doesn’t do much for me.” She held up her police ID and appreciated the respectful nods.

“At work during the day, this is power. At night and off-duty, this is a piece of paper. It offers no physical protection. You know that and so do I.”

Mistry placed her car keys between her fingers and raised her fist to the small audience. “Come on, admit it. Who’s done this walking from the car?”

She laughed, genuinely, when almost every hand in the room went up. “Of course, we’ve all done it, right? Every advantage. Every edge. Every possibility. We weigh them up every single time we walk from A to B, especially when it’s dark. We consider every angle. How close can I park to my destination? Which is the brightest side of the street? Will the shops still be open to give us more lights, more potential eyewitnesses and support? Every footstep. Every glance. Every sound. We’re always on alert, always asking questions. Why is he wearing a hoodie in warm weather? Did he cross the road to be on my side? Should I cross over? Walk quicker? Phone someone? Start running? Or should I rely on our tried and tested fallback of stabbing him to death with the keys to a Honda Jazz?”

There was less laughter now. Mistry’s speech was too close to the bone for many, too accurate. They wanted solutions, not graphic depictions of daily scenarios. 21

“Yeah, OK, bad joke,” she acknowledged. “None of this is funny. I’m guessing you all know why I was invited here, apart from the obvious. I have a vagina.”

Mistry was taken aback by the warm giggling. She would remember the improvised line about her vagina. She took another sip of the bloody awful tea. What was it with community hall meetings and crap tea?

“Two years ago, my family were attacked. I’m sure you read about it.”

The awkward shuffling in plastic chairs confirmed that her audience had pored over every lurid detail.

“A serial killer came after me and my family. My little boy almost lost his life. We survived, but the trauma took its toll. It almost cost me my marriage. It certainly cost my little boy his innocence. But we got through it. We got through it because police officers solved the case. Police officers did their jobs and justice was served. We are not perfect. There will always be bad apples. There are still lessons that need to be learned and mistakes that cannot be forgotten. But equally, I cannot forget that day. And I cannot forget that my first instinct, as a woman, as a mother, was to call the Metropolitan Police Force. It was the right instinct. And I still hope that every mother, every woman, would do the same.”

The applause was generous but confused. The women sympathised with Mistry’s horrific story but doubted the sincerity of her convictions. And so did she. For a start, she knew that she was partially lying. London’s Metropolitan Police didn’t save her son. She did.

But he had helper her.

Local officers didn’t crack the case either.

He did.

That only made her more irritated. She didn’t want to be thinking about him. 22

Fortunately, there were enough raised hands and disgruntled women in the room to keep her occupied. She picked a woman of a similar age, early to mid-forties, in the front row, smiling kindly, in the hope of a benign question.

“Why are you defending a misogynistic organisation?”

“I don’t think that I am. I’m an Indian girl from an Essex housing estate, who rose from a uniformed officer at a Dagenham police station to a detective inspector, leading my own major investigation team at Charing Cross Station. And I would say that …”

“You are a direct beneficiary of affirmative actions, which is great. We all support that. People of colour should be represented in all major institutions, especially women.”

“Thank you. I appreciate that.” Mistry’s tone was sarcastic. Lectures on inclusivity from people of racial privilege still rankled.

“But the patriarchal structure endures. Less than two per cent of reported rapes lead to a charge. And when we do report something terrible, we suffer the victim-blaming bit. We shouldn’t have walked down that street. We shouldn’t have worn that skirt. We shouldn’t have gone to that bar or had that much to drink. We shouldn’t be sex workers. We’re blamed for the perverts and porn addicts that are still being employed at the highest levels of society, in politics and in your police force.”

The spontaneous applause was louder and more sustained than anything that Mistry had enjoyed. She wasn’t angry. She mostly agreed.

“I know, I know,” Mistry said, holding her hands up. “I’ve had my arse pinched at staff parties. Didn’t complain. When I was in uniform and on the beat, walking those freezing streets in a thin white shirt, the blokes would go on about seeing my nipples. Didn’t complain. But then, 23you know what, a dick pic turned up in my email and I did complain. Took it to my DCI and the idiot faced a disciplinary hearing.”

Mistry’s interrogator raised her hand again. “But is he still in the job?”

“Yeah.”

“Well, there you go.”

The murmurs of dissent spread around the room. Mistry was at risk of losing the room. She decided to give a lost cause one more shot.

“Look, I’m not going to lie to you. We’ve still got a long way to go. Women need greater protection, on the street, in the workplace and even within the police force. I’ve worked with a few dodgy guys. We all have, in every workplace. But I’ve also worked with some great policemen too, inspirational blokes, decent, kind, positive people. Not every copper is rotten.”

An hour later, Mistry regretted her words when she discovered that the only lead in an Essex murder case was the pain in the arse that had saved her son’s life.

Chapter 5

Mistry didn’t want to go back. The brick building reflected its surroundings. Dagenham Police Station was a dreary, functional relic of a neglected past. Everything seemed smaller than she’d remembered. The windows. The rooms. The ambition. Everything had shrunk.

Mistry had left the station and the town behind years ago. She had no intention of hanging around. Nostalgia was for the elderly, the nativists and those who didn’t want too many looking like Mistry in their beloved country. Nostalgia was for the threatened and the vulnerable. Mistry insisted that she was neither.

She took a seat in the waiting area and pretended to be deaf. It was an instinctive act of stress relief. She was an Indian woman. Selective deafness was a vital life skill. So she just watched.

“Is that her then?”

The questioner leaned over the station counter, leering at his colleague. They were both young, uniformed officers, probably in their mid-twenties, Mistry reasoned, stocked up on youthful bullshit and local stereotypes.

“Yeah. She knows this Low geezer, apparently. Seems all right.” 25

“Yeah, not bad.” He glanced over his shoulder, casually, but still too obvious. “I wouldn’t say no.”

The detective inspector rose to her feet. “I’m flattered, PC … What is your name?”

“Er, PC Henderson, ma’am.” He stood up straight. “I didn’t mean to … I didn’t know that …”

“I’d be listening? How could I hear anything, being in the same room and sitting a few feet away. Clearly, I’m invisible. I’m just grateful that you acknowledged me, for a second or two. I’m so privileged that you deem me worthy of your erection.”

“No, he didn’t mean that, inspector,” PC Walker said, playing the diplomatic duty officer.

Mistry joined them at the counter. “Do you know what always gets me? It’s not your everyday misogyny. It’s the presumption of my consent. The idea that I’ll be happy to let you give me one, that I’d actually ask you first, beg you by the sound of it, putting you in such a tough position, where you’ve got to actually take a moment, and give me some serious consideration before deciding that, if you had time in your busy schedules, you’d probably do me a favour and give me one.”

Henderson looked up at the ceiling. He saw the omnipresent eye in the sky. Bloody cameras. In the corner, above the duty desk, on their chests, everywhere. Coppers were monitored, day and night. They really couldn’t say anything anymore. The PC in his title meant something else entirely now. His career was in those cameras.

“Sorry, ma’am. I didn’t think you could hear me.”

“Of course I could hear you.” Mistry eyeballed the junior officer. “We can always bloody hear you.”

Walker cleared his throat. “Would you like to register a complaint, Inspector?” 26

Mistry sighed at the shrivelled men. “What would be the point? What would it achieve? Yeah. Exactly. Shall we just crack on? Why am I here?”

Henderson stepped up, eager to make amends. “We found twelve women in a lorry at Rainham Marshes, all alive, which was lucky. But the driver, an IC5, was found dead in his cabin.”

“An IC5?”

“Yeah, Chinese,” Walker interjected. “No ID yet. Doing a fingerprint check, but might be an illegal, so that’ll take time. His throat was slashed with a large blade. Early pathology suggests it was swift, one slash, not a frenzied attack, quite deliberate, almost professional. They had little penknives on them, but too small to do that. Anyway, there was no blood on any of them.”

“Obviously, the murder isn’t on your patch,” Walker continued. “Not anymore anyway.”

“Yeah, I heard you grew up around here,” Henderson remarked eagerly.

Mistry ignored him. “Carry on, PC Walker.”

“Yeah, right, so we’ve tried to interview all twelve women. But none of them are speaking, not one. We’ve had in all kinds of Chinese translators, but nothing, not a single word, except one.”

Mistry nodded. “The one who mentioned Low’s name.”

Henderson and Walker exchanged nervous glances. “Yeah, well, after what happened before, with your family and that, our guvnor got in touch with your guvnor at Charing Cross and that was it. We don’t really know what else to do at this point.”

The interview room was grim. Mistry adjusted her skirt beneath the table. She was surprisingly nervous. She had 27buried her past life at the police station for a reason. There were always too many like PC Henderson and not enough like PC Walker.

On the other side of the table, the Chinese woman’s appearance surprised her.

The woman was still attractive, despite the scrubbed, tired face and the borrowed clothes from a local charity. But she was older than they usually were. Illegals were younger, stronger and more eager to make any kind of living. This woman was around Mistry’s age. Her long black hair flowed down her back. Her nails were recently manicured. Even her eyebrows had been threaded. She chewed gum continuously. She was too polished for a sex worker and too old to fit the Asian village girl archetype. The image was jarring. Nothing matched.

Mistry gestured towards the other, much younger Chinese woman sitting at the table. “Well, we have a translator who speaks both Mandarin and Cantonese, am I right?”

The younger woman nodded proudly.

“But I’m told by the other officers that you understand English, which is great. So let me give you the good news first. You are not in trouble. The knives that you all had in the back of the lorry are too small. They are not the murder weapon. Plus, none of you had any traces of blood or any evidence to suggest you’d even been near the driver’s cabin or his seat. There is a possibility of all of you seeking asylum status in the UK, if you meet the criteria, though the criteria seems to change on an hourly basis. But you had no passports with you in the lorry and you’re all refusing to speak. We can’t identify you. We don’t know who you are. We can’t help unless you speak.”

The Chinese woman folded her arms. Her translator 28muttered advice in Mandarin. She shook her head. Mistry checked her watch. She had promised to pop in and see her father on the way home. He lived nearby; the last connection to a distant past.

“I know Stanley Low,” Mistry said.

The Chinese woman stopped chewing. She was finally paying attention to the Indian copper.

“Detective Inspector Stanley Low. He works for the Singapore Police Force, right? I’ve known him for many years.” Mistry’s words sounded confessional, almost remorseful. “I’ve known him since we studied at university together in London. At least twenty-five years. He’s my friend. Was he your friend in Singapore?”

“Last time.”

The voice terrified Mistry. It wasn’t her words. It was her accent. The woman sounded liked Low.

“Oh, he was your friend last time. That’s great. That’s really great. And why do you want to speak to him now? Do you think he can help you?”

“His people send me here.” She tapped the table hard.

Mistry couldn’t hide her confusion. “Policemen? Policemen sent you here?”

“Pimps.” The Chinese woman spat out the word. “Low was a pimp last time.”

Chapter 6

Dr Tracy Lai noticed a change in appearance. Low had made an effort. The stubble and unkempt hair were still there, as always, but the inspector had at least graced their appointment with clean clothes.

“You look well.” The psychiatrist wasn’t lying.

“What can I say? Life’s been good to me.”

Lai always found her patient amusing. His intellect was a polarising, divisive quality, but his mood had improved of late. The wearying, misanthropic sarcasm had almost given way to self-deprecation. Almost.

“I raided an illegal KTV lounge this morning. Arrested half a dozen sex workers, a few pimps, some punters and a CEO from a well-known multi-national corporation,” Low said, counting off the arrests on his fingers.

“Sounds interesting.”

“Sounds like a dull Monday morning in Singapore.” Low stretched his legs. He hadn’t bothered with sleep. He needed to come down first.

“You seem bored.”

“I am bloody bored. I was doing this shit twenty years ago and I’m doing it again, wasting my time, sweeping up piles of ants. Next week, there’ll be another raid, 30another pile. I don’t work for the police. I work for Rentokil.”

Lai had noted some time ago that her patient’s rage often gave way to a degree of resignation, even melancholy. That could be worse from a medical standpoint. The anger gave him a target, a focus. Now he didn’t particularly care.

“We talked about this before, keeping perspective,” Lai said softly, straightening her skirt. “Two years ago, your career was done. You said so yourself. They had put you on some speakers’ circuit, to get you out of the way, according to you. And then you got involved with that London case and everything changed.”

“Yeah, I saw her again.”

Low always saw her. Now she was in a psychiatrist’s office, sitting across from him in an executive leather chair. Perfect hair. Impeccable dress sense. Taking notes. Judging him.

“I know. You told me.”

“She reminded me of you.”

“You’ve told me that, too.”

“Or you reminded me of her. I knew her first, right? Anyway, you both have a lot in common.”

“Such as?”

“You don’t put up with my bullshit. That’s the first thing.”

“You like independent women?”

Low considered the question. “Nah, too obvious. Bit too textbook for you, that one. It’s more than that. You don’t need me. I almost forget what that feels like.”

“I don’t understand.”

Hunched in his chair, Low peered up at his confidant. He was no longer obligated to see a psychiatrist. He was no longer working undercover. The original order, from 31an old boss in the corruption unit, lapsed years ago. But he had nowhere else to be.

“A woman was raped this morning.”

Lai couldn’t hide the horror. She was trained. Instructed. Never look away. No clues. Open face. Blank canvas. But Low saw it in her eyes. He usually did.

“Yeah. I know,” he continued. “But she wasn’t raped, not in a legal sense. There was consent. Sort of. There were pre-existing conditions, to use the popular phrase. She’s a foreigner working illegally as a KTV hostess, whatever that means. And he was her pimp, whatever that means.”

“What does that mean?”

“It means we ignore her and he owns her. She doesn’t exist. She isn’t real. And if she isn’t real, he can do whatever he likes. Play out his Pornhub fantasies whenever he likes. He beats her. She bleeds. She wipes away the blood and they start again. That’s the agreement. And I sit here with you, two elite-school kids, sharing my first world problems about an ex-girlfriend like a needy teenager.”

“So you have to save a rape victim to feel needed?”

Low almost laughed at Lai’s bluntness. He pointed a patronising finger at her instead. “Now that one was good. That’s why I come here, to get the juices flowing. Yeah, I need rape victims to play the great male saviour, right? That’s good. I’d probably reach the same conclusion in interrogation. But that’s the difference between your world and mine. You still think these people can be saved. She knows she can’t. I could’ve destroyed him. But she wouldn’t press charges, wouldn’t even tell me his name. So, no, I don’t want to save rape victims to feel needed.” Low looked away. “It would be nice just to feel needed.”

Now it was Lai’s turn to lean forward. “That sounds like self-pity.” 32

“No, it sounds like a sleep-deprived detective who spent the early hours kicking a rapist in the balls.”

The psychiatrist offered a kind smile. “Well, I hope you found the target at least.”

“Every bloody time,” Low said, appreciating the levity.

“Do you still miss her? Ramila Mistry?”

“Wow, that was a punch in the face. You even said her full name, too. Double jab. Bang. Bang. I’m impressed. You go subtle with the balls joke, lull me into a false sense of security, and then you kick me in the nuts.”

“Metaphorically speaking.”

“Yeah, well, metaphorically speaking, no, I don’t.”

“You don’t miss her?”

“No, I don’t miss her.” Low registered the surprise. “You don’t believe me?”

“Did I say that?”

“Your raised eyebrow did.”

“We often end up talking about her. You just said I reminded you of her.”

“You also remind me of an old auntie who never gave me hong bao at Chinese New Year and I don’t miss her either.”

“But you still remember her?”

“Of course. Her breath stank of durian and she always kissed me on the lips. You’d remember her, too.”

Lai chuckled. “And she didn’t even give you hong bao?”

“Gave me nothing. Just sat in the corner with her soggy lips playing mahjong.”

“And Ramila?”

“She never had soggy lips. Or played mahjong.”

“How do you feel about her now?”

Low scratched the back of his head in irritation. “I feel like she’s happily married with a cute kid and an idiot husband. Why would I begrudge her that? She’s settled over 33there. I’m raiding KTV lounges over here. Everyone has moved on, except you and your A-level psychiatry.”

Low almost believed his words, too. He believed them when his phone buzzed in his pocket. He believed them when he swiped the screen. He believed them right up until the text message appeared.

It’s Ramila. It’s urgent. Call me now.

“Oh, fuck,” Low said, already on his feet.

With a heavy sigh, Dr Tracy Lai closed the door on her lost patient.

Chapter 7

Heathrow Airport was always cold, especially at dawn. And the road outside was full of startled Singaporeans struggling with the cold. Low watched them all, throwing suitcases to the floor and scrambling for extra layers. He saw himself doing the same, a quarter of a century ago, in a different life.

Faces changed. Behaviour didn’t.

Singaporean travellers still arrived wearing the wrong clothes at the wrong time of day. Those raised in an air-conditioned nation struggled with any temperature that couldn’t be controlled.

Low stomped his feet and pulled on his hoodie, but it made no difference.

England still got into his bones.

“No loitering. No loitering.”

The voice was grumpy, a walking, talking hi-visibility vest ushering guests away from the road and out of the way. His message was unequivocal.

Welcome to England. Now piss off.

Low identified with the bluntness. It reminded him of Singapore.

While those around him hurried to follow orders, Low 35gripped his tea and waited. He savoured the cup’s warmth. He wasn’t sure how much he’d get from her.

He didn’t even recognise her initially. Different car. Different haircut. Same face. There was only so much she could change.

He threw his overnight bag into the back seat. No child seat. Time had passed.

Low opened the passenger door and hesitated.

“I think you can sit in the front,” Mistry said, looking up at him. “Hurry up, before I get a ticket.”