Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

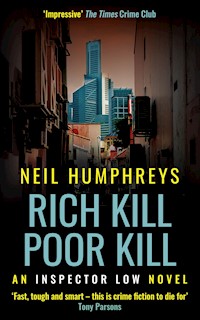

- Herausgeber: Muswell Press

- Kategorie: Krimi

- Serie: An Inspector Low Novel

- Sprache: Englisch

When a foreign worker is found dead in a Singapore back street, nobody cares. The police dismiss it as just another underclass slaying until more victims appear, all killed with the same weapon. Singapore suddenly faces its first serial killer in decades, and the authorities are desperate. In desperation, they turn to the one man they despise almost as much as the killer himself: Detective Inspector Stanley Low. His career is in ruins, his bipolar disorder is barely under control, and he's as angry and unrepentant as ever. But he's also the only detective capable of understanding what drives this murderer. Racing against time, Low must navigate Singapore's stark income divide, where even death discriminates between rich and poor. He needs to solve the case quickly, stop a serial killer who's targeting the city's most vulnerable, and somehow hold onto his sanity. A dark, disturbing examination of inequality and injustice, Rich Kill Poor Kill reveals the brutal reality behind Singapore's economic miracle and asks uncomfortable questions about who matters—and who doesn't—in a society obsessed with wealth.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 353

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

RICH KILL, POOR KILL

An Inspector Low Novel

Neil Humphreys

Contents

Glossary of popular Singapore terms and Singlish phrases

(in order of appearance)

Lah: Common Singlish expression. Often used for emphasis at the end of words and sentences.

Talk cock: To speak nonsense.

Prata: A fried pancake usually served with a fish- or meat-based curry.

Aiyoh: To express frustration, impatience or disgust.

Cheem: A Hokkien expression used when someone or something is deep, profound or particularly clever.

Ang moh: A Caucasian (literal Chinese translation is “red hair”).

Wah lau: A mostly benign expression that can mean “damn” or “dear me” in Hokkien. (See wah lan eh for a more vulgar variation.)

Kakis: Buddies or mates.

Catch no ball: From the Hokkien “liak boh kiew”, the expression means to not understand at all.

Sarong Party Girl: A derogatory term used to describe Asian women who go out with Caucasians and adopt western affectations.

FT: Foreign talent.

Tekan: A Malay term to hit or whack someone, but not always in the literal sense. Tekan means to abuse or bully. An abusive workplace might be accused of having a “tekan culture”.

Kelong: A colloquialism for cheating, corruption or fixed, often used in a sporting context. (In Malay, kelong is a wooden sea structure used for fishing.)

Xiao mei mei: In Mandarin, it means little sister. On seedier websites and blogs, it can also refer to attractive women and prostitutes.

Longkang: The Malay word for “drain”. But longkang is commonly used to describe man-made water passages.

Basket: A local, more benign euphemism for “bastard”, often used to express one’s frustration.

Owe money, pay money: A popular expression scrawled on the walls and doors of debtors’ homes by loan sharks.

Ikan bilis: The Malay term for anchovies, but often used to describe something small or a skinny person.

Kan ni na: Perhaps the most abusive phrase in Singlish. It can mean “fuck you” or “fucking” (e.g. Kan ni na ang moh).

Jia lat: A Hokkien adjective meaning to sap energy and used to describe something that is exhausting, troublesome or time-consuming (also written as jialat and chia lat).

Chao chee bye: In Hokkien, chao means smelly and chee bye is the rudest term for vagina.

Gahmen: A colloquial term for the Singapore Government.

CPF: It stands for Central Provident Fund, a social security savings plan for Singaporean citizens and permanent residents.

Tahan: Malay expression meaning to take or endure. (e.g. cannot tahan roughly means cannot take it.)

Hao lian: Arrogant.

Siu mai: Pork dumplings.

Ah beng: A popular stereotype, an ah beng is often depicted as a scruffy, skinny Chinese guy who favours Singlish and Hokkien vulgarities.

Teh tarik: A popular tea in Singapore, particularly at roti prata stalls. Literally translated as “pulled tea”, the hot, milky drink is poured into a cup from a considerable height, giving it a frothy, bubbly appearance.

Lelong: In Malay, lelong means “auction”, but it is also a common Singaporean term for selling something cheaply.

Teh-c: Tea with evaporated milk and sugar.

Sotong: A popular seafood dish. Sotong is Malay for squid. But it is commonly used to describe an idiot, often by saying, “Blur like sotong”.

Ah long: Loan shark (in Hokkien).

Kiasi: In Hokkien, kiasi means “scared of death”, a criticism directed towards someone for being cowardly.

Kiasu: Singaporean adjective that means “scared to fail” in Hokkien.

Wah lan eh: A naughty relative of wah lau. In Hokkien, it means “oh penis” or even “my penis”.

Mat salleh: In Malay, a pejorative term for a Caucasian.

Shiok: A fantastic, wonderfully pleasurable feeling.

Towkay: The big boss or leader (in Hokkien, towkay means head of the family).

Laksa: A rice noodles dish served in a curry sauce or hot soup.

Ice kachang: A dessert of shaved ice covered in colourful fruit cocktails, toppings and dressings.

Chapter 1

Talek Maxwell closed his laptop. The reflection in the screen was annoying him. He knew he had aged, but at 3am he looked dreadful. The dark puffs beneath his blood-streaked eyes hardened his already coarse complexion. Some of the old handsomeness remained, but he had stopped posting Facebook photos. The broad-shouldered, muscular swagger of Chatham Boys’ rugby captain had gone, replaced by a fat, balding, angry stockbroker. The English private schoolgirls once called his name from the touchline. In Asia, they shouted “white man” over their loud mini-skirts. He once had the prefects. Now he had prostitutes. He paid them to take him back. For a night, he was the captain of the team again. In the morning, he at least had the memories.

Aini wandered past the dining table. Pencil-thin with small breasts, her nakedness usually aroused Maxwell. But it was late. And he had seen himself in the reflection. She leaned over the breakfast bar, her chest brushing against the kettle, and grabbed the percolator.

“You want coffee?” she asked.

“No.” Maxwell didn’t bother looking at her.

“I want coffee,” she said.

“I gathered that. Any chance of you putting some clothes on? I do have neighbours.”

“You say you like it.”

“I like it on Saturday night, not when I’ve got to be up for work in three hours.”

Aini turned on the tap and filled the percolator.

“I’ve got to be at work in three hours too.”

Maxwell snarled a little. “You’re already at work.”

Aini hit the percolator against the marble breakfast bar.

“I am not a hooker OK.”

“So what are you doing now? An impression?”

“I am a cleaner. I clean apartments. That’s how you meet me, OK.”

Maxwell peered down at his stomach and flicked the waistband on his boxer shorts.

“Met me. It’s ‘how you met me.’ Past tense. You can’t even speak properly.”

Aini muttered something under her breath.

“Don’t start your Bahasa shit. I know you’re criticising me when you start waffling on in your own language.”

Aini was suddenly embarrassed by her nakedness.

“Why you treat me like this? Why you so mean to me?”

Maxwell stood up and violently pushed his chair under the dining table. The timber chair legs screeched along the tiled floor.

“Mean to you? What is this, primary school? Grow up.”

“Me grow up? You are the child. You are the one who so nasty.”

“Is. For god’s sake, it’s ‘is so nasty.’ I live in a first-world country where no one can string a proper sentence together.”

Aini felt the shame. She hated this man, hated him. But she needed him and so did her family. She pointed towards the bedroom.

“You never make fun of me in there. In there, you don’t complain what I say.”

“Maybe in there I’m too distracted thinking about the meter.”

“What meter?”

Maxwell was lunging forward fast enough to alarm Aini, joining her behind the breakfast bar. He jabbed a chunky finger towards her groin.

“That meter there, the one between your legs, charging me by the hour.”

“I am not a prostitute OK.”

“No, of course you’re not. I just buy your clothes, and your shoes, and give you extra for remittance, and give you money to buy your boy something for his birthday, or for his first day at school, or for another birthday. He has more birthdays than the bloody Queen and he’s probably not even your son.”

Aini suppressed the anger, considering her response. She appeared to rise slightly. She looked at Maxwell. Sweat pulled clumps of his chest hair together. He disgusted her.

“He is my son,” she whispered.

She pushed the percolator plug into the socket and flicked the switch. The unexpected bang made her scream. She ducked as sparks danced in the air.

“It’s only a blown fuse, you silly cow.” Maxwell brushed past her and pulled the plug out. He yelped as he dropped the plug.

“Ah, you bastard, it’s hot,” he shouted. “You see? Are you happy now? You can’t even make a cup of coffee without blowing up my apartment.”

“It was an accident.”

“You’re an accident.”

Maxwell pulled open a drawer near the sink and rummaged around. He took out a long, slender Phillips screwdriver with a yellow handle and bent over the blackened plug socket. He tapped it with the screwdriver handle.

“Look at this. I’m gonna have to replace this now. That’s more money, isn’t it? Plus the coffee pot might be blown. Put all that in with the remittance money I gave you, and it would’ve been cheaper to pick one up at Orchard Towers.”

Aini moved the percolator away from Maxwell’s hefty frame as he leaned on the breakfast bar. He began to unscrew the plug socket plate.

“But no, I’ve got to pay for one with the world’s smallest tits who can’t even make the coffee.” He sighed. “In some ways, it’s not even your fault. It’s my fault. Asia has done this. Too much money, too much cheap food and too many cheap women like you. You should’ve seen me before I came out here, at university. I was unstoppable. I had them all, on their knees, rugby firsts, cricket firsts and Kelly Stewart. Best-looking woman in the college, daughter of an old Tory boy and I had her first. And now look at me.”

He stopped to face Aini.

“I’m in a sweaty apartment at 3am with you. It’s like swapping champagne for a pint of warm piss.”

“You want me to leave?”

“No, please stay. I paid for the full night, didn’t I?”

Maxwell leered at her. The tears in the Indonesian girl’s eyes pleased him. He returned to the plug socket.

“Does your son know what you do? Surely he doesn’t think you make all your money from cleaning expats’ condos. When he opens his birthday presents, does he know they were paid for by a fat white man you fuck at weekends?”

Maxwell heard breaking glass behind him. He reached around to feel the water already trickling down his back. The percolator hit him again, smashing against his fingers. Glass splinters pinched all over his back. He turned towards Aini and smiled. She swung again. He threw up his left arm and watched as the flesh opened up beside his elbow. Aini was screaming. He couldn’t really hear her. But he was sure she was screaming. His neighbours wouldn’t like that.

Using his good right hand, he picked up the screwdriver and stopped her screaming.

Chapter 2

Slumped in his office chair, Detective Inspector Stanley Low picked up his obituary. It was written on his new name cards. There they were. The words on his death warrant: Technology Crime Division. The Singapore Government had a sense of humour after all. He couldn’t be fired. He had too many notches on his truncheon. The Tiger Syndicate and the Marina Bay Sands murders made him a recurring character on true crime TV dramas. But cybercrimes was worse than a sacking. It was a living death. The desk job came with rigor mortis. Low had lived his investigative career outside of an office. Now he was dying in one.

His stained T-shirt was not as messy as his desk. In open defiance of his anal, geeky, computer-obsessed director, Low ran a loose ship. His workspace collected pizza boxes. His spreadsheets were dotted with coffee stains and he could never find his files because he never kept files. He was tasked with finding online hackers, invisible seditionists and confused, loud-mouthed teenagers. He had effectively been spayed like a whiny stray. His tool was always his tongue, but it had been ripped out.

Low opened the boxes and tipped out the name cards across his desk. Using them as Frisbees, he flicked them one at a time at the heads of colleagues peeking above their cubicles.

“Come on lah, Stanley,” a voice shouted.

“Trying to work over here,” cried another.

He childishly sniggered. “It’s 3am, go home already.”

“You go home. Learn how to use a computer.”

Low craned his head to locate the heckler.

“Eh, balls to you. No need. I got you to wipe my arse for me.”

Low found the silence crushing. No one really bantered with him at Technology Crime Division. They were boring and he pulled rank. Singaporeans didn’t make fun of their superiors, even in a jocular environment, even if their superior happened to be a government pariah and an alcoholic mess. Just in case.

Low swigged from a plastic water bottle on his desk and shuddered. He smelled the vodka. His own breath left him nauseous. The phone made him jump, but he was eager for the distraction.

“Hello … Ah, yeah, working on it now. You know it’s 3am, right? No, I appreciate that, but do we have to shit ourselves every time there’s a negative story? I know the Minister shouldn’t have commented on low-paid workers, but she’s always talking cock. Election coming is it? I’ll check the websites again. Couldn’t get interns for that? No, I’ll do it. It’s 3am on a Monday morning, what else would I be doing, right? But can I ask one thing, ah. Wouldn’t it be easier if you just fired me?”

The sudden dial tone made Low smile. His cheeks burned as he savoured his childish victory. They hated him, but they couldn’t quite get rid of him, not yet. He tapped his keyboard and the blog reappeared on his screen. Low refreshed the page for updates. The homepage had the Singapore flag as a background with an index on the right listing the latest insalubrious stories involving beer sellers from Mainland China sleeping with their coffee shop customers, Filipino nurses criticising Singaporean “dogs” and teenage anarchists mocking religious leaders; same shit, different names. Even the website’s name irritated Low. The Singapore Truth. True news for true Singaporeans.

He picked up the phone and waited for the answering machine.

“Hello, I know you’re not there, I know it’s 3am and I know this isn’t an emergency,” Low muttered. “But if I have to read one more racist blog, I will kill everyone in this office. Let me know when I can see you.”

Low returned to his screen. Fuck you, The Singapore Truth and fuck your racist followers.

Low manically scooped up as many name cards as he could. He stood up and started throwing handfuls around the room, flicking them towards office cubicles.

“Hey, got a new name card, must take ah. Singapore style, everyone must take my shiny new name card.”

He spotted a colleague with oily hair peeping at him from above his terminal.

“Hey, computer genius, you want my new name card? There you go.”

Low was hurling bundles of name cards at the nameless guy.

“Got enough or not? Hey, Alan Turing, you want more or not? You know who Alan Turing is? No, of course not, you’re a first-year computer grad. You are sitting here at 3am because you can’t get laid out there. All networking? Eh, you want to network, take my new name card.”

The guy ducked as the name cards sailed over his head.

“No, don’t duck, Alan. Take my name card, will be very good for your career. Everybody knows me. The Minister is my good friend.”

Low swigged from his bottle again. He flinched before picking up the last of his name cards.

“Come on, no one wants my name cards? They will get you out of here. You don’t want to get out of Technology? You don’t want to get a girlfriend, is it?”

As the last of the name cards fell, everyone else at the Technology Crime Division returned to work. No one criticised or comforted the inspector. They left him alone. They all hated him that much.

Chapter 3

Maxwell held Aini in his arms. He pressed her head against his bare chest. Her eyes had saddened him. They were confused, pathetic even. She lifted her hands to his chest and gently pushed away. Her blood covered them both. It had stuck to Maxwell’s chest hair, which peeled away from Aini’s neck. She tried to scream, but couldn’t find the sound.

“No, it’s OK, it’ll be fine,” Maxwell said.

He tried to pull her towards him again, but she recoiled this time. She stood still in the minimalist apartment as blood seeped from her wound and trickled down her legs. A red streak snaked its way across the kitchen’s marble tiles towards Maxwell.

“No, no, no, we can’t have that,” he whispered.

Maxwell walked quickly along Spottiswoode Park Road. He adjusted the suit jacket he had thrown around Aini’s shoulders and buttoned across the front, covering her dark T-shirt and the stain beneath. Her tight, dark blue jeans absorbed most of the blood around the waist. Any patches were hard to see in the darkness. The drizzle helped. Chinatown was mostly deserted. But there were 24-hour coffee shops filled with dozing taxi drivers and a handful of bookies even at 3.30am. They were nearby, but not near enough. Maxwell paid $8,000-a-month rent for a reason. As he passed the deserted, silent restored houses of the private Blair Plain district, he cherished the exclusivity. Questions were rarely asked of anyone living in such neighbourhoods, not in Singapore.

Aini’s head rolled towards her chest.

“No, no, no, stay awake, Aini, it’s going to be fine.”

Aini’s eyes were closing.

“I’m tired Talek.”

“No, you’re not tired. You’re fine. Everything is fine. We’ve just got to get you somewhere, somewhere nice.”

Aini tumbled towards Maxwell. Her legs buckled like a new-born foal. Maxwell propped her up, ignoring the searing pain in his back. He knew his black T-shirt was sticking to his bloodied skin. He hoped the jean jacket offered enough cover.

The distant streetlights of Kampong Bahru Road danced before Aini’s eyes.

“I can’t see anything,” she whispered.

“It’s dark, just dark.”

Maxwell realised the scraping sound was from her stilettos. He was dragging her. Taxi drivers might assume she was drunk. The gallant white man had offered his suit jacket and was chaperoning her home.

“I’m so tired.”

Aini’s eyes closed.

“No, it’s OK. Wake up, Aini. You must wake up now, it’s OK. You can’t go yet, not yet.”

Maxwell heard the sound of a TV coming from the prata shop on the corner. Plates were being stacked. He also picked out voices. The lights were too bright. He dragged her towards an alley behind the prata shop.

“This will be OK. This will be a good place to rest.”

The odour of the dank alley stunned Maxwell. Cockroaches scattered as he pulled Aini’s failing body past fruit boxes filled with food scraps. He propped her against the wall of the prata shop and lowered her across an open drain. A rat scurried away through the foul, stagnant water.

“Just wait here for a minute, just for a minute.”

Maxwell stepped back, utterly exhausted. His breathing was laboured. He ran his fingers along the spine of his T-shirt. They were damp with sweat and blood. He examined his hands. Most of the blood wasn’t his. He bent down beside Aini and washed his hands and arms in the drain.

She stirred.

“My boy,” she whispered.

Her voice unnerved Maxwell. He grabbed a nearby plastic barrel and hoisted himself up. His hand slipped into the barrel and he recoiled in disgust. The barrel was filled with the prata shop’s dirty crockery. Its cold water was curry red. Chicken bones and used tissues floated on the oily surface.

“My beautiful boy,” Aini muttered.

Maxwell watched her closely. Her head had rolled towards her left shoulder. She couldn’t move. She was almost certainly dying now.

“He is a beautiful boy,” Maxwell agreed, examining her broken body.

“So beautiful.”

“He takes after his mother.”

As Maxwell moved towards the plastic barrel, he thought he saw Aini smile.

“Talek, can you?”

“Of course. I have the address.”

Maxwell crouched beside Aini and pulled her towards him. He took back his jacket and hung it on a crate. He dragged the plastic barrel away from Aini. The slop spilled over the sides and splashed onto his trainers. He jumped back to spare them.

“Photo.”

“What’s that?”

“My boy, pocket.”

Aini tried to lift her arm, but her strength had deserted her.

“Yes, the photo in your pocket, of your boy, yes, I like that one.” Maxwell flicked a cockroach off the rim of the plastic barrel. “You want me to get that photo for you?”

Aini said nothing. Maxwell grabbed the sides of the plastic barrel.

“That’s the one with him holding his new football right, with his friends in the village. Lovely photo. Make sure you look after that one.”

Maxwell pushed the plastic barrel over.

The oily, curried water washed over the dying woman. The grubby plastic plates and cutlery clattered against her body. She slid along the wall until her right arm and shoulder wedged in the narrow drain. Maxwell picked up the plastic barrel and shook it over Aini’s body until the last half-eaten chicken wing had tumbled out.

Satisfied, he rinsed his hands in the drain a second time, picked up his jacket and returned home to clean his apartment.

Chapter 4

“Why do they always leave them in alleyways,” Professor Chong said theatrically to the investigators squeezed around him in the confined space. “And why does the Major Crime Division always send too many men down an alleyway? Can I have some room please gentlemen?”

Asia’s leading pathologist used his gloved hands to usher the crowding officers away. The white-shirted men moved back. In crime and punishment circles, Chong commanded reverence. From his earliest days as a cadet dealing with Toa Payoh’s cult killings, his professionalism demanded respect. His portly frame and avuncular personality made him every officer’s favourite uncle.

“Thank you, boys. Let the old dog see the poor rabbit.”

Chong was a happier man these days. Nearing retirement, he had found a cottage with his English partner in the East Sussex countryside, not too far from Brighton, where they had married a year earlier. After that wretched business at Marina Bay Sands, Chong was insistent that he scrubbed the stains away with a long vacation. His partner suggested a cottage in Kent and surprised him with a marriage proposal. They still couldn’t get married in Singapore of course. Technically, they still couldn’t have sex in Singapore. But the public mood was softening beyond the increasingly marginalised fundamentalists. Chong knew that. So did the fundamentalists, who tried to shame him by regurgitating old stories on vulgar blogs using uncouth language. But Chong’s civil partnership ceremony was covered, to his surprise, by all the major newspapers, including the Chinese and Malay press. The overwhelmingly positive response had privately reduced him to tears. And the archaic jokes had mostly dried up at crime scenes, at least to his face.

With considerable effort, Chong kneeled beside Aini’s crumpled body and sighed. It never got any easier; more detached, yes, but never any easier. He gestured towards an assistant to take notes and photographs as he spoke into an iPhone.

“A young Malay woman, presumably in her late 20s, maybe early 30s, slim, with no obvious wounds except the solitary wound in her chest. It’s a round puncture, rather than a slash, suggesting a sharp-tipped instrument, such as an ice pick or a screwdriver, rather than a knife, and it was pushed in far enough to catch her lung, resulting in heavy blood loss, more internal than external due to the size of the entry wound. She probably didn’t die immediately; she might have had some time while the pleural cavity filled up. There’s blood in the mouth and on the teeth. She probably spat out quite a bit before she died. Judging by the wound, she probably wasn’t attacked here. Even allowing for the waste-water washing away a lot of the blood, there’s still not enough either in the alley or out in the street. No. She wasn’t killed here.”

Chong followed a voice in the background and found a familiar face. He rose slowly.

“Detective Sergeant Chan, I heard you were with the Major Crime Division now, the murder squad no less. How are you, young man?”

Charles Chan was aware of the audience in the alley. He was also aware of his recent promotion. He had earned his stripes quicker than those around him.

“It’s Inspector now, actually, Professor.”

Chong smiled and patted his hand warmly.

“For Marina Bay Sands?”

“That and one or two smaller cases.”

“You’re being modest. I read the papers. Working with that old scoundrel James Tan obviously helped in the end.”

“It did, sir. Working with him and, you know, Stanley Low, I got, how to say ah?”

“Both ends of the spectrum?”

“Exactly. So you don’t think the girl died here either then?”

“No, there’s not enough blood here.”

“We found some spots out in the street. The killer washed down most of it around here, but missed a bit in the darkness. How long you think she’s been dead?”

“Around four, maybe five hours now.”

Detective Inspector Chan stepped back as Chong’s assistant took photographs. He folded his arms.

“Yeah, table cleaner from the prata shop found her. From China. At first, scared to tell his boss, then scared to tell us, usual lah, over here on social visit pass, no work permit, no declared income. The prata shop staff said the victim never came into the shop, never seen her before.”

“You believe them?”

“Not really.”

Only now did Chong notice the puffiness around Chan’s face. He was still attractive, but heavier, darker. The boyishness was fading.

“So what do you think?”

“Ah, same as everyone else here. There’s no CCTV in the prata shop or around here and we got no ID on her yet, just some photos in her pocket, but this is a very ulu side. Once you get away from the houses, it’s quiet streets and open fields until you reach Tiong Bahru, not many cars or witnesses, got privacy, empty streets, places to park cars. Why else would you come here? Go coffee shop first maybe. Argue over price. Fight. Dump her in the alley. Finish.”

“I’m impressed, inspector. You don’t sound like the old Charlie Chan anymore.”

He didn’t. Even being called Charlie Chan didn’t bother him anymore. The job had desensitised him. He was becoming immune to criticism and crime scenes. He had a second child on the way and his wife wanted their Punggol apartment renovated. She had told him to get his priorities sorted out. He needed to spend more time discussing nursery colour schemes than dead prostitutes. Something had to give.

“In this job, no choice right. How long for the lab report?”

“Ah, not too long, you need it in a hurry?”

“Not really. If she’s a foreign prostitute, they won’t make her a priority.”

Chan gently patted the pathologist’s shoulder. He stepped over the corpse and wandered out of the alley. He needed some air.

Chapter 5

Dr Tracy Lai nodded and thought about her next appointment, the pervert in denial. He still protested his innocence, even with her, despite two convictions for taking up-skirt photos on shopping mall escalators. He insisted the photos were accidental and his dutiful wife had stood by him. They had three children and had recently moved into a condo with a partial view of the Bedok Reservoir.

But the up-skirter would offer a welcome reprieve after Detective Inspector Stanley Low.

She took the longest showers before and after his sessions. She could never be clean enough. She had no qualms about wearing skirts for the up-skirter, but rarely on days when Low was scribbled in her diary. He undressed her psychologically and left her feeling unworthy and cheap. More than that, he made her feel unprofessional. Her doctorate, which she hung so proudly in her office withered away whenever he flopped into one of her leather armchairs. He penetrated her. He weakened her. Her affluent, sheltered background reeked of bullshit. She couldn’t wash it away. She was always left with a residue of phoniness. He was the real deal, a raw, natural intellect capable of understanding his own case file, blessed and cursed with the ability to harness his bipolar condition for his own ends. And it made him such a prick.

“Have you slept yet?” Lai asked.

Low rubbed his bloodshot eyes and slid further down the armchair.

“What for?”

“Have you been working all night?”

“You know I have.”

“Sleep deprivation can be a contributing factor in a manic episode.”

“So can having a shit job, but you never ask me to quit.”

“It’s not getting any better?”

Low turned away slightly and smiled. “I work for the Technology Crime Division. The Technology Crime Division. Even the name is boring.”

“A desk job may be less stressful for you right now. It’s a change of pace.”

“It’d be a change of pace if I stuck a fucking chopstick in my eye.”

“We talked about the language before, didn’t we?”

“The what?”

“You said the f-word again.”

Low laughed loudly and clapped his hands. “Aiyoh, the great Asian hypocrisy strikes again. I know we’re all full of shit outside, but now we got to bring it in here? We keep half the country in poverty and the other half in denial, but we can’t say the word, ‘fuck’. Because that will be our downfall, right? That will be the moment when the sunny island sinks, when we all start saying ‘fuck’ to each other. How’s your up-skirter doing?”

“I don’t talk about my other patients in here.”

“He’s your patient. But he’s my case, remember? I caught him last time, thanks to my hard drive-cracking geeks in the office.”

“He’s not your case anymore.”

“No, he’s yours. You try to keep it clean in here, right? You don’t want to sully yourself with sick people saying sick words. You think you can spray nice words through the air like disinfectant and keep it clean, is it? My job is shit because it stops me from catching up-skirt, photo-taking bastards like your patient. Your job is to make them better, find their redemption, find their good side like Darth fucking Vader. I catch them. You make them feel good. And you want to give me shit for saying ‘fuck’?’”

Lai considered her response carefully. “Feel better?”

“No.” Low bit the inside of his cheek. “Do you really think there’s a point to all this? You think we can be cured?”

“Not cured.”

“Yah lah, yah lah, not cured, treated. I know the drill already.”

“To a certain extent.”

“Anyone? Like Adolf Hitler or the North Korean with the funny haircut?”

“Those are extreme examples often cited when someone seeks to disparage the treatment of mental health, but that’s exactly what they are, extreme cases. You don’t think you are getting any better?”

“It depends on the circumstances.”

“Nurture over nature?”

“Not so cheem, just a fucked-up life over a good life.” Low raised his hands in apology. “Sorry, a messed-up life over a good life. See? I feel better already.”

Lai smiled. And then felt terrible for smiling.

“What do you think?”

“Please lah, the same as you when you put away the textbooks,” Low said, sitting up. “I’ve got this website now to monitor, The Singapore Truth, you heard of it?”

“I’m familiar with it, can’t say I read it regularly.”

“But you do. We all do. We say we don’t, but we do. My guys have the stats to prove it. The site gets more unique visitors than all other mainstream news sites combined. And it’s shit, right or not? Racist, sensationalised shit. Every day it’s the same. Send back the Indians, the Filipinos, the Indonesians buying our condos, the Bangladeshis scaring our women in the shopping centres, it’s all bullshit. But we read it. We check with the tech guys overseas and it’s the same everywhere—blacks and whites in the US, asylum seekers in Australia, Eastern Europeans invading England and France, the Mainland Chinese taking over Hong Kong, the Islamic State taking over the world—same stories everywhere, right? Globalisation makes us all fear being swamped by the invader, right or not?”

“Perhaps.”

“Please lah, we monitor. It’s the same all over. Almost overnight, we are all racist again, even in Singapore. You think that’s true?”

“No.”

“No. But The Singapore Truth website says we are. That blog says we must make Singapore for Singaporeans and take the country back before it collapses. And do you know why? Do you really know why one country is supposedly being overrun with racists?”

“Go on.”

“Because one Chinaman’s wife got shagged by a white man.”

Chapter 6

Harold Zhang sat on the side of his bed and watched his wife get dressed. Li Jing was still so beautiful. That’s what hurt the most. If she had gone to seed, he could channel his infuriating sense of impotence and fling it back in her fat, saggy face. He could make her understand how she had scooped out his insides in Australia and left him empty. She had disembowelled him. He didn’t think it was possible to loathe another person quite as much as he loathed his wife. But she was still so beautiful.

The early-morning sun streaked through the grilles of their bedroom window and her face glowed. Zhang continued watching as his wife brushed her tousled hair, still damp from the shower. He wanted her, right now, with her damp hair and her clingy underwear and her tight thighs and her pink cheeks and her early-morning bloom.

And he despised himself for it. He controlled Singapore from his laptop, but she still controlled his loins. He’d do anything to lose the puppy-dog adoration that emasculated him. Out there, he was the blog master. In here, he wasn’t even the master of his own bedroom.

“Very nice,” he said.

“Hmm?” Li Jing muttered, still brushing her hair in the mirror, not bothering with eye contact, reasserting the balance of power.

“That underwear, very nice.”

“Yah.”

“Where you get it?”

“Don’t know. Had it long time already.”

They had been married for 15 years and always struggled with small talk. After Australia, it was agonising.

“It’s nice.”

“Yah,” Li Jing muttered as she grabbed a couple of clips from the dresser and pulled her hair back tightly.

“Got yoga today?”

“Yah.”

“Same instructor?”

“Yah.”

“From China?”

“Don’t start, OK.”

“I won’t, I won’t. Just don’t know why we cannot find a local yoga instructor to give lessons at our local community centre.”

“Maybe because we think a yoga job not good enough for our children.”

“Maybe. Maybe got no choice.”

“Look, I’m not doing this again, OK. Save it for your blog.”

“OK. I’m sorry.”

“Yah.”

Zhang tried to look away as his wife bent over to pull up her Lycra leggings. But her tautness teased him. His old friends—the ones he had left—their wives had lost their figures. Childbirth, reunion dinners and hawker centres all stuck to their hips in the end. But his wife had always taken pride in her appearance. Good genes gave her the complexion and the slim build. Bad genes gave him the potbelly, the receding hairline and the myopia. He knew strangers played the numbers game with them. He watched their cogs turn. He heard their voices in his head: What was she doing with him? She was at least a seven. He was barely a three. It must be the money. He’s got that famous blog. It must be the money. Can’t be anything else. Just look at them.

He always anticipated the scrunched faces as they registered their disgust, unable to hide their contempt for the middle-aged, balding, fat xenophobe dragging around the beautiful, reluctant wife. Zhang didn’t mind. He agreed with them. He had to shave in the mirror. He saw what they saw.

But they were only half-right. It wasn’t his weight gain or the hair loss. She wasn’t superficial in that way. Her beauty made it easier for her to be less vain. She radiated natural confidence, not artificial arrogance. It was the ugly ducklings that chained themselves to mirrors in a desperate search for swans. Li Jing didn’t care about her appearance, because she didn’t have to.

And then she went to Australia and found herself; found the mirror image of herself in another man.

He was a surfing instructor, taking out coach parties of Japanese and Chinese tourists who could barely swim. He was shabby, bearded and wore faded T-shirts and shorts all year round. None of his clothes were branded. Some of them came from second-hand shops. He didn’t own a computer and his phone was an old, cracked Nokia. His battered Ford was more than 10 years old and rarely washed. He had built his seafront shack himself. He ran his surfing business by placing ads in the local newspaper. He didn’t even have name cards.

Zhang didn’t understand him at all and thought the surfing lesson was pointless. Li Jing fell in love with him almost immediately.

She started private surfing lessons. Zhang started his blog soon after, from a suburban home in Australia. He called it The Singapore Truth. It was the right time for true Singaporeans to take back Singapore. The website was worthy and necessary, and Zhang couldn’t find a job in Australia.

He squeezed the side of the duvet as his wife pulled the leggings towards her hips.

“Wah, you still look good, ah.”

“Hmm.” Li Jing focused on her sweat top.

“Still got a bit of time before work.”

“Not really.”

“It won’t take long. Definitely will not take long.”

“No time really.”

“Made time for him though, right?”

Zhang spat out the words. Li Jing stopped.

“Maybe I’m the wrong skin colour,” he went on. “White is right?”

Finally, Li Jing gave her husband the attention he craved. She looked at him. She had once loved this man.

“I’m going to work.”

She didn’t look back.

“Yah, and who owns your company again? Who’s your boss again?”

Zhang heard the door slam and got up. He shuffled into the office and opened his laptop. Anti-government activists monitored and updated The Singapore Truth for him overnight. Bigots and fundamentalists were always his favourite volunteers. Their contributions usually garnered the most hits. He didn’t even correct the dreadful syntax, knowing it further irritated the English-educated, bleeding-heart liberals. True believers were the best. They answered to a higher ideology. It would only undermine their purity to pay them.

He clicked on the latest news and there was the headline.

young woman killed in chinatown

He read the story and learned only in the second paragraph that she was a cleaner from Indonesia, so she was probably working illegally in the country. And she was a foreigner. That should’ve been in the headline. He’d speak to the fool who uploaded the story later.

But an illegal worker had been murdered. And she was a foreigner. Zhang smiled and settled down for a productive morning’s work.

He had needed cheering up.

Chapter 7

Dead bodies no longer bothered Chan, but the smell still lingered. He applied some Vicks VapoRub beneath his nostrils. Professor Chong rolled his eyes.

“What? This is good for the sinuses,” Chan said. “They do this in the US, you know.”

“Only in the movies, my dear boy.”

Chan didn’t want to admit the truth. He hadn’t picked up the idea from the movies. The stench of a rotting corpse had driven him to distraction for months until he watched a Liverpool match and saw that a couple of the players had rubbed Vicks VapoRub on their jerseys, just below the neck, to help their breathing. He tried it once at a police morgue and it immediately blocked out the dead. Now he never left home without it.

“Eh, it works OK. Don’t smell them anymore.”

“Nor do I,” Chong replied.

“Really? What’s your secret?”

“Almost 40 years of experience. Are you ready?”