8,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Verve Books

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

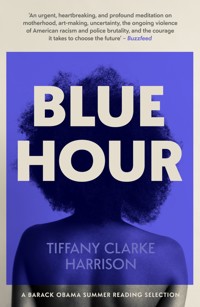

** ONE OF BARACK OBAMA'S SUMMER READING SELECTIONS **

What is motherhood in the midst of uncertainty, buried trauma and an unravelling America? What it's always been – a love song.

Our narrator is a gifted photographer, an uncertain wife, an infertile mother, a biracial woman in an America that's coming undone. As she grapples with a lifetime of ambivalence about motherhood, yet another act of police brutality makes headlines, and this time the victim is Noah, a boy in her photography class.

Unmoored by the grief of a recent, devastating miscarriage and Noah's fight for his life, she worries she can no longer chase the hope of having a child, no longer wants to bring a Black body into the world. Yet her husband Asher – contributing white Jewish genes alongside her Black-Japanese ones to any potential child - is just as desperate to keep trying.

Throwing herself into a new documentary on motherhood and making secret visits to Noah in the hospital, this is when she learns she is, impossibly, pregnant. As life shifts once more, she must decide what she dares hope for the shape of her future to be.

Fearless, timely, blazing with voice, Blue Hour is a fragmentary debut with unignorable storytelling power. The perfect next read for fans of Raven Leilani's Luster, Jenny Offill's Weather and Bernardine Evaristo's Girl, Woman, Other.

'A portrait of determined creativity and the attempt to live authentically in a changing world. It's full of zest and keen observation, with a likeable, intimate tone that cuts through its potentially dark subject matter' - FINANCIAL TIMES

'Gasp-worthy… How did Harrison achieve this spectacular feat of emotional withholding while also making readers feel so much?' – VULTURE

'Incredibly powerful' – GOOD MORNING AMERICA

'A brave new writer' – PUBLISHER'S WEEKLY

'An urgent, heartbreaking, and profound meditation on motherhood, art-making, uncertainty, the ongoing violence of American racism and police brutality, and the courage it takes to choose the future' – BUZZFEED

This novel contains depictions of police brutality and miscarriage.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 177

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Ähnliche

Praise for Blue Hour

‘Full of musings, debate, anger, distress and yet, ultimately, hope, Blue Hour is incredibly powerful’ Good Morning America

‘This assured and highly interior novel unfolds in a series of short paragraphs, emotionally charged scenes, and poetic fragments… It’s an urgent, heartbreaking, and profound meditation on motherhood, art-making, uncertainty, the ongoing violence of American racism and police brutality, and the courage it takes to choose the future’ BuzzFeed

‘Gasp-worthy… How did Harrison achieve this spectacular feat of emotional withholding while also making readers feel so much?’ Vulture

‘With every word, Blue Hour cautions against holding back: from being seen, heard and understood; from persevering in spite of forces that would see you destroyed; and from expressing love on every possible occasion, before your chances run out’ Chicago Review of Books

‘In the vein of Jenny Offill and Raven Leilani, Harrison’s debut offers an intimate slice-of-life portrait with no easy questions or answers. A poetic novel that dances on the edge of hope and despair’ Kirkus Reviews

‘In lyrical language, Harrison skillfully explores the complex tensions that gnaw at the expectant mother and offers an intimate view of the couple’s pain. This signals the arrival of a brave new writer’ Publishers Weekly

‘Blue Hour is a pulsing and powerful novel about grief, motherhood, storytelling, and self… A short, beautiful, intensely present work of art’ Lydia Kiesling, author of The Golden State

‘Blue Hour is a poetic and feverish debut, a story that laces together the struggles of marriage and motherhood, art and artist, race and violence in America into a powerful web, much bigger and stronger than its slender spine would suggest. If you loved Dept. of Speculation by Jenny Offill, the work of Rachel Cusk, or Luster by Raven Leilani, this book is for you’ Ashley Warlick, author ofThe Arrangement

‘In a world full of demands and distractions, Blue Hour asks us to pause and sit with our grief. Challenging, intimate, and relevant, this novel is a meditation on the boundaries of hope’ Osa Atoe, author of Shotgun Seamstress

‘An exquisite, melancholic portrait of motherhood and marriage for a biracial woman in America. Tiffany Clarke Harrison writes about miscarriage with fleshy, beating rawness, leaving us painfully undone and beautifully seen. Blue Hour has captured the dark question of modern motherhood amid police brutality and racism in America – do we really want to bring kids into this? There is no other book I’d rather read than hers’ Sarah Hosseini, writer, journalist, and professor

For my grandparents Audley and Agnes Webster

All art is a kind of confession, more or less oblique. All artists, if they are to survive, are forced, at last, to tell the whole story; to vomit the anguish up

– james baldwin

This novel contains depictions of police brutality and miscarriage.

Part I

The therapist asks how I feel, and I tell her, dismembered. I do not know where the pieces have been discarded. Even if I did, how would I begin to put them back together?

All the king’s horses and all the king’s men…

For days in my head, this rhyme.

It all started with The Metamorphosis.

You were sitting in the back office of your store, Meir, chain-smoking at seven in the morning, waiting for me to take photos for a magazine. The editor had told me little about you except for your name, Asher Fromm, and titles: tie designer, owner. Despite the bell’s jangle, you hadn’t heard me come in. You always say you noticed my hair first. You say it billowed and rolled like a cloud down my back, and then you coat my neck with kisses. I stood in front of the bookshelf at the entrance, intrigued by your attempt at cleverness or culture. A large plant leaf obscured half of the top shelves, and books with torn spines were stacked beneath chairs. It was a men’s clothing boutique, not a bookstore, and you’d written WORDS FOR EVERY MANon a cut piece of chalkboard that hung from twine on a tack. I picked up The Metamorphosis, opened it, and put the pages to my nose, inhaled.

‘What are you doing?’

‘I like to get acquainted with a space before prodding its intimate corners with a lens.’ I removed the book from my nose, leafed through the pages. I had yet to look at you. ‘It’s not the fifties, but a certain amount of modesty and manners still goes a long way.’

I put down the book, plucked another from the shelf, and ran my fingers along the spine. Music played. Guitars and drums.

‘Your store is gorgeous. The classic novels are a nice touch. It’s like a tailored rock star, a hipster, and a member of the Nation of Islam walk into a bar – and read Hemingway.’

‘God, you’re strange.’

I turned, glimpsed your face.

‘It bodes well for me.’

‘I’m Jewish, though, not Muslim. So it would be more like “a tailored rockstar, a hipster, and a Jew walk into a bar.”’

‘I’m Black, Haitian, Japanese. So now that we’ve got our census information out of the way, where would you like to start?’

‘I like you.’ You smiled.

The feathered scar on your jaw was my favorite.

In a few months we would be married. Stand before a judge. Me in black combat boots and a white mini dress, and you in a trim burgundy floral print suit. We linked arms and held hands. Repeat after me, the judge said, and we repeated. Recited vows as somewhat strangers, then family. I could hardly bring my tongue to curl around the word family, project it. So why do I consider it now? Why do I consider my parents and sisters? Our baby, dead before birth? Now as the world bears down on Black bodies (another man killed), and I am tired. Now that I’ve had enough.

You read aloud to me on the couch, squinting through glasses at the words by the dim stutter of candlelight. The power was out, a storm, and our apartment glowed gold with swaying flames on the shelves, with sprawling plants and piccolo, and on the hearth near the leaning stack of found paintings and frames. The moon was high, clear. The steady sheet of rain had thinned. You read from your favorite book: A Sport and a Pastime. The dropout bathes the French girl. His prick goes into her, and he discovers the world. My legs were draped across your lap and you stroked my shin and knee. I was on my back, the linen of my robe pulled open. Exposed. A patch of dark grew tangled between my legs. I turned and saw myself in the mirror of that leaning stack, my face splattered with freckles, and turned back to you. ‘I’ll read,’ I said, and thumbed through the pages. I responded with raised hips, pauses between words, to your fingers inside me, your mouth.

This is pre-miscarriage when we insisted on late nights and liquor and displays of whatever the hell we wanted. Like the first time Meir made a coveted list in a national magazine, and damn if you couldn’t stop touching me; hands hovering and gliding inside my coat, and along the thin cotton of my dress as we hurried to a dinner party, thirty minutes late. You are the punctual one, but that night our lateness was your fault. You insisted on lathering every bend of vertebrae and my skin in your scent. At the party, I had gone to the bathroom and when I came out you were drinking and laughing with a friend on the fire escape. An entrepreneur friend from college who wanted to invest in your business so you could open a second store. The night, beautiful and crisp, ushered a breeze into the party. I said hello, held your elbow, and pressed my lips to your cool ear. ‘We have to go. I’m spotting,’ and later I delivered a pulpy plum-sized sac on our bathroom floor. We put it in a glass jar as instructed and took it to the hospital. You handed the jar to the doctor and said, ‘Here’s our baby.’ You didn’t open a second store after that. We said we’d wait for life to be normal again but failed to say what that meant.

‘I never thought I wanted children,’ I say to the therapist.

‘Why is that?’

The sac on the bathroom floor, on those tiny black-and-white square tiles and under the pipe bending down from the sink. I see it. My insides on the outside, like looking at my muscle. I’d squatted there, gripping that pipe, and when I felt the sac release, I kicked it away with my bare foot.

I tap my finger against the leather of the couch. ‘Did you hear? The guy they shot in the parking lot of a grocery store yesterday, the one getting into his car or something, he died this morning in the hospital.’

Her cheeks are flushed and pinker than I remember in her photo online. Her dark chest is large, and the buttons across it strain with each inhale as she waits.

‘I hurt people with my selfishness,’ I say.

‘How so?’

I laugh. ‘It’s still pretty early in our relationship, let’s pace ourselves.’

‘Ah, silly me.’ She smiles, tapping her forehead with her fingertips. ‘All that “the truth shall set you free” bullshit can’t be rushed.’

I make a Neanderthal sound, somewhere between a grunt and a laugh, grinning. How dare she build rapport with me? Sneaky little therapist.

The truth is, the moment I first saw you dance wild with arms darting, hair flopping in your laughing face, I knew I wanted a clone of that uninhibited joy to grow inside me. I had decided against having children years ago, right after the abortion. This was before I knew you, but then after I knew you, I started to change my mind. Yes. I could be a mother. Yes, I’d changed my mind. Could my malfunctioning body and the reality of this American nightmare change it back?

‘My husband loves me, but my blood rejects me.’

‘Can you elaborate?’

‘They die. Or willingly let me go.’

‘You’re referring to your family’s car crash? Your parents and younger sister.’

‘And the baby. And my other sister. My own body. It doesn’t want a baby, and nobody can tell me why. Why doesn’t it want to have a baby?’

‘Do you want to have a baby?’

‘Yes. But I am afraid.’

‘What are you afraid of?’

‘It’s like after they died and left, everything in me shut down. It didn’t know how to function.’

‘Why?’

‘Why what?’

‘Why don’t you know how to function?’

‘Isn’t that your job to figure out? How the hell should I know?’

‘Because you do know, and it’s my job to get you to see it. So, as early as it is in our relationship, I’ll be up front and let you know that telling me a bunch of facts isn’t going to get you there. Feeling something will. So I’ll ask you again, what are you afraid of?’

I am exhausted and don’t feel like talking anymore. The therapist waits. It is only our third session, but I’ve caught on to her. She will always wait me out.

‘I had a dream once,’ I say. ‘After the crash, I dreamed that I opened my mouth so wide that you could see all the way down to everything I’d ever thought but never said and it was horrifying being that human. Like my muscles were on the outside. Have you ever seen a muscle? The raw flesh of it? It’s disgusting.’

●

You like abandoned things. Hidden things. Tucked away and forgotten things.

In the beginning, we rode the Triumph into the city as you took me on a tour of your favorite hidden places. A garden at the bottom of a gravelly hill on the West Side. You’d once sketched designs for ties there, and started smoking, and wrote songs until you realized you were terrible at writing songs but kept up with the smoking and tie sketching. Dank alleys, all mildew and garbage, were favorite spots to watch the sunset the year you dropped out of school. NYU. You became a line cook instead at some hot shit restaurant in Manhattan. Rich, middle-aged white women who got sad sometimes talked to you there. They wanted to have fun with the young tattooed guy who flipped their salmon on the grill and drizzled it with lemon-garlic butter and capers, who now smoked in the alley. They’d flirt and you’d flirt to make them feel good. You’d let them touch your hair, sandy brown and clumped with sweat, always falling in your eyes.

And there was the warehouse. Peeled paint and textured, cement walls, floor. It was winter when you took me. Wind burst through broken windows. It howled, scraping against jagged edges of glass. ‘My dad taught me how to play chess here,’ you said. ‘In the winter because he wanted to test myability to focus.’ You pulled a tiny wooden case from inside your jacket and sat on the gray ground. Never mind the dust, debris. You opened the case. Chess pieces toppled on the soft red velvet. ‘Would you like to play?’

I sat and you asked about my parents. I told you my father grew up in Haiti and laughed a lot. He was a boxing trainer. My mother was born and raised in New York by my Japanese grandmother and her family. My mother’s grandparents hated her, ostracized her, called her the Dark Devil. A lot of people in their community did. She loved her mother, my father, and my sisters and me more than herself.

I asked about your parents. You said, ‘In the end, they didn’t like each other much.’

There was a student of mine, Aja, who had the biggest Afro I’d ever seen, the perfect sphere. Two months ago, I had taken a few students to that abandoned warehouse and she was the only one to use the backlight from a window to frame her subject. I told her it was smart of her and she said, ‘Smart?’ ‘Yes,’ I said. It was the first time in months of classes I’d seen her smile.

Soft-spoken with squinty eyes and purple high-top sneakers, Journey took photos that felt live, in real time. Ray was slightly deaf in his right ear and liked photographing dead pigeons. Keeva spilled the developer, and Sarai hung her photos equidistant with clothespins on the string.

And Noah. He waited for the other boys and girls to leave the mobile darkroom (an old food truck I’d refurbished to teach my photography classes). They would make fun of his sensitivity. He inched over to my hip, head lowered and shoulders crouched as if to protect his heart, and lifted the photo in his hands, presenting it to me like a gift. The photo was of a little girl jumping rope on an empty sidewalk. She wore a blue cotton dress with white tennis shoes, white socks. Weeds bent, parched from the summer sun, in the cracks beneath her hopping feet. She laughed wide-mouthed. Two of her top teeth were missing. Noah said, ‘When you’re alone, you can be anything you want.’

That night, next to you, you said I was groaning and kicking in my sleep. The sheets, my T-shirt, and hair were saturated with sweat, and my body heaved. You shook me and I woke, giddy yet terrified, searching the emptiness between my legs. You asked if I was dreaming and I said no. But I lied. I dreamt of horses and the baby we’d lost. How the horse pushed him out of her body, and he dropped to the ground, thrashing and sticky. Ready to run.

Times Square is shut down. Only foot traffic is permitted to pass. The streets are tightly packed with bodies in various stages of mourning, outrage, and disbelief. Packed for Noah. I take their photos. Noah’s mother had been on the news. She’d sent him to buy milk for his baby sister. She told him to buy a treat with the change because she knew how disappointed he was that the free photography class he’d signed up for that weekend, my class, had been canceled at the last minute. My fertility specialist wanted to see me. She could get us in earlier than expected.

It rained on and off all day, that day at the fertility specialist. It was a surprise, the rain, and men, women, and children scurried throughout the city sidewalks with drenched hair and soggy shoes. You held the door open to the doctor’s office. My boots squeaked against the bright white of the linoleum. We walked side by side, holding each other down the hall. I leaned into you and said, ‘The brown, inexplicable boogie woman’s going to trap you. She’ll slip into your dreams and make you love her. Like the Sirens circling beneath the sea and tugging at your silly little ship.’

Apparently, I still believed in miracles. That too was a surprise, and I was afraid.

Across town, the corner boys followed Noah, knocked the milk out of his hands before punching him in the jaw, in the nose, in his ribs. They laughed and left, dumping the milk out along the sidewalk. Noah readjusted his glasses, held his side, and hobbled the long way home in the opposite direction. When the cops hung out their windows and told him to stop, he did. ‘Why the bloody nose?’ they asked. ‘It’s nothing,’ he said. ‘Really, nothing?’ ‘Really.’

I find you in front of two older couples whose wide-stretched hand-holding unintentionally blocks the side-walk. Your head pokes out over the rest. Your hazel eyes, a complicated mélange of muted earth tones behind glasses, watch a woman, a teacher from PS eighty-something, speak into a microphone. She reads from a list of names, ending with Noah’s. Critical condition. Shots to the back for reaching for the chocolate bar in his back pocket. I clutch my abdomen and say it, the statement I’ve thought no fewer than six thousand times since we left the doctor and Noah’s name bled against the television, the internet, the world.

‘If we don’t get pregnant, I don’t want to try again.’

‘What?’

‘I can’t try again.’

‘Why? What’s going on?’

‘I can’t bring a kid into this. I won’t.’

The night air is rich with heat and humidity. Foreheads and cheeks glisten with sweat. The speeches end and we walk toward the subway. The crowd marches, thousands of people holding one another, chanting, and carrying signs. I’ve gotten ahead of you, snapping photos, and twist around to see you lumbering several feet behind me. Colored, flashing lights of billboards reflect in your glasses. When you see me, you catch up and hold my hand.

Voices raise. A scuffle. A shout rings out, shattered glass, and a bang. The herd of bodies thickens and shifts in an agitated wave as police storm the streets. A gray cloud of gas explodes into the air. Everyone runs, screams. A high-pitched scraping of vocal cords and eardrums, deep-bellied, animal cries. I let go and lose you, stop and stand in the middle of the sidewalk clicking, clicking, clicking the camera. A stampede. A woman – I see her. On hands and knees, retching and blinded by gas, gripping the gravel, screaming for help and he kicks her. A black boot to the jaw and a baton at her back. Mouths pull open with rage, and I begin to rush to her, but someone scoops her up, blood flooding her mouth. It spills down her neck as she’s flung to some false sense of safety. I turn and a cop car pushes forward. Pushes. Pushes into the bodies standing arm in arm. They let each other go and push back, but it is no use. I run toward them as bodies fall. Shots. You yell my name from somewhere behind me and it is a ravaged, strained sound. You grab my arm. We run. I am too slow and you grip my hand so tight, crushing bones.

A little boy holds on to his father, legs and arms wrapped around him as they flee. The father, his eyes red and tearing, mere slits in his panicked face, grips the boy in a full embrace, squeezes him to his chest. Is he crying from tear gas? Or are they actual tears? Because he knows he can never fully protect the child. None of us can. We can barely protect ourselves.

●

The therapist keeps a rubber-band ball on the table beside her rattan chair. She only uses gray and white bands, and it is bigger since the last time I was here. I tell her about Noah in the hospital. She asks about the protest. I don’t talk about it much. I tell her about the woman who was kicked in the face by the cop. I see it every time I step outside. I walk a lot, to meetings and appointments, and I see her everywhere. She had wavy blond hair that was pulled back at her neck and the way she was bent over, on all fours on the ground, it almost seemed like a tail, it was so long. Her fists were full of the street, black with the street, and she hollered and cried, and he kicked her so swiftly. Kicked her right in the jaw, and her neck snapped to the side. Baton to the back. Twice. Baton to the legs until she was flat on the ground, barely moving. That’s what I tell the therapist.

‘How did it feel to see that?’

‘I mean, it was awful. How else is it supposed to feel?’

‘What does awful feel like to you? In your body?’

‘It doesn’t matter.’

‘It does matter. If your being here for an hour every week is going to mean anything at all, it does matter. We’ve talked about intellectualizing over feeling. It’s a defense.’