4,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Aurora Metro Books

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

"I collected the first bone when I was twelve. This fact was not mentioned in court... Such a tiny little bone, more like a tooth. I only kept it to keep him safe."

Kathryn Darkling, imprisoned in Holloway, is facing death by hanging for her vengeance killing. Haunted by a spirit, she still hopes to perform the ancient black magic that will free her soul, or her struggle to punish the mighty will have been in vain. Will the love of her life come to her aid?

Or can she find a way to escape her fate?

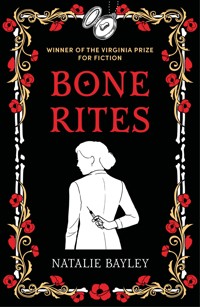

Winner of The Virginia Prize for Fiction, Bone Rites is a dark, literary tale of love, loss and one woman’s obsessive fight for justice and redemption within a ruthless world.

5/5 stars *Possible spoilers below* I LOVED this book. I loved the style, the writing, the Gothic horror, the protagonist, everything about it. Bone Rites is told through the eyes of a British noblewoman, Kathryn Darkling. Kathryn is a morally complex protagonist with a bit of a ghost problem. She wants to do everything possible to save her brother, especially because she considers herself responsible for his death. I loved the “deathbed confession” style of writing in this book. I’ve always loved the unreliable narrator types, and Kathryn is a perfect example. Check this book out if you’re a fan of Gothic/magic/historical fantasy. Thank you again to NetGalley for giving me an ARC of this book.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Ähnliche

NATALIE BAYLEY

Natalie Bayley is the author of Lolita’s Daughter, The Secret Life of Grandmothers, The Witch Who Saved Paris and The Lady Lyttle Murder Mystery series.

Her novel Bone Rites has had an interesting literary journey of its own beginning when inspiration struck while sitting in a cave. An early draft was selected for the 2019 Blue Pencil longlist, then a revised draft was shortlisted for the 2021 Blue Pencil First Novel Award. The Caledonia Prize recognised its promise and longlisted the manuscript also in 2021. Undaunted, Natalie edited and polished the novel further and entered the manuscript to the Virginia Prize for Fiction in 2022, which she won, thereby securing publication with independent publishers Aurora Metro in London.

Natalie lives in Sydney, Australia, where she teaches English, enjoys ocean swimming and whispering to cats.

Follow @NJBayley

First published in the UK in 2023 by Aurora Metro Publications Ltd.

80 Hill Rise, Richmond TW10 6UB, UK

Bone Rites copyright © 2023 Natalie Bayley

Cover image: Sze Hang Lo © 2023

Cover design: Sze Hang Lo © 2023 /Aurora Metro Publications Ltd.

Editor: Cheryl Robson

All rights are strictly reserved. For rights enquiries please contact the publisher: [email protected]

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form, or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise) without the prior permission of the publisher. Any person who does any unauthorised act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages.

In accordance with Section 78 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, the author asserts her moral right to be identified as the author of the above work.

This paperback is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, resold, hired out, or otherwise circulated without the publisher’s prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

Printed on sustainably resourced paper

ISBNs:

9781912430871 (print)

9781912430888 (ebook)

Acknowledgements

Many thanks to Cheryl, the Aurora Metro team, and the Virginia Prize judges for recognising something worth celebrating in this strange tale.

To all my first readers — especially David, Leesl and Tracy —thank you for your time, your attention to detail, and your bravery in giving feedback. Many thanks also to the gifted screenwriter, Nicolas Mercier — your knowledge, encouragement and faith in me has kept me going over the years. Merci beaucoup mon ami!

Huge thanks to my dear Victoria in Victoria, the talented author Victoria Reeve, who is the kindest, most patient writing pal a girl could have.

To Justin, for everything

CONTENTS

Acknowledgements

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Chapter 29

Chapter 30

Chapter 31

Chapter 32

Chapter 33

Chapter 34

Chapter 35

Chapter 36

Chapter 37

Chapter 38

Chapter 39

Chapter 40

Chapter 41

Chapter 42

Chapter 43

Chapter 44

Chapter 45

Chapter 46

Chapter 47

Chapter 48

Chapter 49

Chapter 50

Chapter 51

Chapter 52

Chapter 53

Chapter 54

CHAPTER 1

1925: Holloway Prison

I collected the first bone when I was twelve.

This fact was not mentioned in court. No crime was committed, so far as I know. Such a tiny little bone, more like a tooth. I only kept it to keep him safe. I wish I still had it, but it’s long gone. It’s all long gone now.

They have announced the date of my execution. I have just two more weeks in this hag-ridden castle. Two weeks! I never expected things to progress this quickly. It’s not that I fear the noose – far from it – but I cannot die until my work is done. Yet how is it to be managed in so short a time? The prison governor has been unsuccessful and there has been no reply from Scotland. I have failed on every level. I know I deserve to be punished, but not yet. Not yet.

I must find a way out of here.

A jangle of keys. The heavy iron door creaks open. I ready myself. It’s madness to think I’ll be able to escape so easily, but I’m willing to try anything. But instead of the young gullible skivvy, the wardress herself is bringing in my lunch slops. I slump back down on my iron bed, knowing full well that I have no chance of getting past her. She is almost as tall as me and twice as wide. And she’s no fool. She knows full well what I’m capable of. And yet today, her air of gleeful disdain has been replaced by resentment. Why? My breathing quickens – is there a letter from Scotland? But she has other news.

‘The Guv’nor’s finally found a chaplain what’s brave enough to take your last confession.’ She slams the slops on the table, then pauses, expecting a reaction. I do not oblige, even though my heart is pounding in furious delight. ‘Now you can atone for your crimes, can’t ya? And beg for God’s forgiveness.’

She spits on the floor.

‘I do not believe in God.’ I reply before I can stop myself. Fool! Will I ruin this before it even begins?

But she just laughs.

‘Well now! You can tell him that when you see him.’

‘The chaplain?’

‘No, God.’

I turn my back on her, but you cannot walk away in Holloway. Cannot slam a door in a temper. Those luxuries are gone, along with so many others.

When she is gone, slamming the door shut with a clang, I hug my knees. Finally, just as I was about to give up hope, they’ve found me a chaplain. It has begun. But do I have enough time? And what will this brave man be like? What will he expect me to say? That I am sorry for everything I have done? I am not. That I regret it all? I do not. There is only one thing I truly regret. The first bone.

CHAPTER 2

1905: The First Bone

It’s summer 1905, and my little brother, Frederick, is just six years old. I’m twelve, almost an adult, and like any big sister, I adore and loathe him in equal measure.

We’re not allowed below stairs, but Nanny gets lonely up in our draughty nursery and often sneaks us down to the warm, jam-sweet air of the kitchen. Cook never complains because she’s convinced the kitchen is haunted and hates being alone. Nanny laughs at Cook and Freddie is too young to be interested in ghosts, but I long to witness some sign from the spirit world. A jolly, approachable ghost (like Sir Simon de Canterville in Oscar Wilde’s The Canterville Ghost) would be a great diversion. Sadly, although Cook’s fear is genuine, her ghostly evidence has not yet been persuasive. The gardener proved the strange smell she blamed on supernatural emanations was caused by an infestation of mice and that the unholy howling of some devilish fiend was nothing more than a stray cat. But I live in hope. I need this house to be noteworthy in some way.

Today, Freddie is bored of the kitchen and wants to play outside. He whines and kicks me under the table while I try and amuse him with bits of dough and apple peels. Nanny and Cook ignore us. They drink tea and talk about our parents. I’m not supposed to be listening, but of course I do.

‘She married too young, of course, beautiful, but impatient. She’s no’ even interested in these two bairns, barely looks at them. It’s no’ right.’ Nanny whispers.

Cook sniffs.

‘Aye, she’s playing with fire, that one. Parties every weekend. And her a married woman of twenty-nine! When my own mother was her age she had eight children and a farm to run.’

Cook glances over at us. I focus on the table, studying the nicks and slices her knives have made in the grain. When she speaks again her voice is so low Nanny has to lean forward, but I can hear her every word, hissing like the blackened kettle on the stove.

‘The Master’s too old for her. She’s bored of him and bored of the weans too. This won’t end well – you mark my words.’

I roll my raw dough thin, like a worm, and began to eat it like a child. Freddie, noting everyone’s inattention, slips down from the table and creeps into the laundry room. The mangle at Darkling House is a vast mechanical beast and it holds a great fascination for him. The smooth wooden handle, the intricate cogs and most of all those great wooden rollers, squeezing out water from sodden sheets. The knowledge, most of all, that it is forbidden. Dangerous. What tempts us more than that? I watch, eating my worms of dough, as he approaches the machine.

Cook and Nanny are right of course. Father is almost always away on some kind of business and Mother is a mystery, seen only at sunset. A clink of ice in crystal, the softness of satin and fur, the musk of perfume, the long-fingered hand, sparkling with diamonds, reaching down to pat my head or pop a chocolate into my greedy mouth. But even that stopped after Freddie was born. Despite Father’s delight that he finally had an heir, Mother appeared uninterested in my fascinating new playmate. She handed him straight to Nanny and kept to her room for months. Since then, I’ve never been called down from the nursery for sunset petting in the elegant drawing room. No more chocolates either, just boiled fish in the Nursery and the rough rustle of Nanny’s starched apron. I still miss those soft jewelled hands stroking my cheek, “Such a pretty child, don’t you think she looks like me?” But Freddie barely knows who Mother is. Nanny is the one who strokes his golden curls as he clings to her long serge skirts. This makes it all the harder for him when she’s told to leave.

Freddie’s screams have given way to gentler sobbing, when Mother finally appears in the kitchen. Nanny is comforting Freddie and bandaging his bloodied right hand, when, cool as ice, Mother orders her to stop, get her things and go. Freddie has to be pulled away from Nanny by Cook and he starts screaming all over again. Mother holds one hand to her head and tries to ignore him. Before retreating back upstairs, she dismisses the poor, young maid too, for mindlessly turning the mangle’s handle. No one listens as I try to explain that it wasn’t her fault – the girl isn’t much older than me, and no taller. She was swamped under vast acres of wet sheets, her little feet sliding on the wet tiles as she fed the mangle’s greedy maw. What I don’t say is that I was the only one to see little Freddie. I knew what he was up to from the start, but I didn’t stop him. I’ve always wanted to know what happens if you stick your finger into the turning rollers.

As it happens, not much. There’s very little blood, only one sheet has to be rewashed. The problem is that the tip of one finger, his right index, is squashed beyond repair. I check it for him each day, neatly bandaging it as Cook showed me, but the blood can’t get into it anymore. It goes from white to green and then black. Freddie cries all day and all night from the pain, but Nanny is gone, Cook is too busy, Father is away, and Mother “Simply can’t abide grizzling”. I try my best. I sing to him, I make up stories about pirates and fairy kings, I steal a whole pot of jam from the larder and feed it to him with a spoon. But he’s not interested in my songs or my stories and the jam makes him sick all over the white coverlet of his bed. Cook spanks me and makes me wash the coverlet myself. I do not use the mangle.

After two weeks, Freddie’s finger smells like the cellar after weeks of rain. I make my decision and go down to the kitchens.

‘Cook?’

‘What’ve ye done now?’

‘Nothing. But we have to call the doctor. Freddie’s finger’s gone bad.’

‘Are ye mad? The Master and Madam are both away. I can’t go calling doctors at the drop of a hat. The fuss the Master makes if I waste a single egg, he’s not going to be happy paying out a guinea for the doctor to come out here on a wild goose chase.’

But I insist. I find the chapter on gangrene in Father’s encyclopedia and I read it to her as she inspects his finger.

‘It says, The tissue of the gangrenous part will swell and blister. There may be pus and a terrible odour.’

Cook’s face is lemony.

‘They’re right about that. But surely a poultice will fix it? I’ve plenty of cabbage leaves.’

‘No. Once the affected limb has turned black, the tissue is dead. The limb itself cannot be saved, but it is of the utmost urgency that the corrupted part be removed from the body so that the gangrene will not spread. Early amputation is essential to avoid death by sepsis. We have to call the doctor, Cook, and we have to call him now.’

She gives me a strange look and crosses herself as if in the presence of a changeling child. I fold my arms and wait.

‘Alright, so. I’ll do it. But you’ll be the one he spanks when he comes home.’

Much to Cook’s surprise and not at all to mine, the Doctor agrees with my diagnosis. I’ve been firmly instructed to stay out of the nursery, but I’ve hidden in the linen cupboard. I watch through the keyhole as he gives Cook his verdict.

‘Has to be amputation I’m afraid. His father…?’

‘Away, sir, on business.’

‘And Lady Darkling?’

Cook looks at the floor. She knows full well where Mother has been for the last few days and who with. Town gossip being what it is, the Doctor probably knows too. He sets his Gladstone bag down on my bed and strokes his beard.

‘Then I am afraid we shall have to proceed without their permission. I’ll need some boiled water and somewhere to wash my hands.’

They leave. I emerge from the cupboard to find Freddie reduced to a small lump of misery under the covers. I sit on the bed, fold back the sheet, and stroke his damp curls.

‘Don’t cry, darling. The doctor will fix you up. Be a brave boy for your Sis.’

He sits up and clings to me like a barnacle. His undamaged hand clings onto my plait as if it were a golden rope he could climb to freedom. It hurts, but I don’t remove his hand. It occurs to me that he needs me, really needs me, and I am filled with a fierce joy. He presses his face onto my chest and his tears stain the lace on the bodice of my pinafore. I rock him gently in my arms.

‘Shush darling, be brave. Everything’s going to be all right.’

I hear footsteps. I gently untangle his fingers from my hair and climb back into the cupboard. I just manage to pull the door closed as Cook and the doctor come into the room.

Freddie screams immediately, before the poor man has had a chance to open his bag. It’s worse than the fuss he made when Nanny left, even though I have explained to him that the doctor must remove the bad flesh to stop the rot spreading. I peer through the keyhole again. Cook is holding Freddie down as the doctor quickly and neatly removes the end of his finger. The surgery looks very professional, but poor Freddie’s yells are so loud I can hardly focus on the doctor’s work. He’s not using a knife, or a small saw, as I expected, but a device that looks like a pair of nutcrackers with a long, crane-like beak. I long to inspect it; there must be a blade inside that beak to gouge out the bone.

At first, I’m annoyed with Freddie for making such a fuss, but when the finger is severed and I can see the ugly gap in his little hand I finally realise that Freddie, my perfect Freddie, who is yet to lose a single milk tooth, has been reduced. His finger will not repair itself like a cut cheek or a scabbed knee. It will not grow back. It has gone forever.

Stricken with guilt, I search my mind for a solution. And then it comes to me. Whilst looking for information about gangrene in father’s library, I briefly perused an old leather-bound book titled Bone Rites. The title seemed promising, but the dusty pages and strange illustrations looked like unscientific mumbo jumbo, so I rejected it. Father inherited half the books in his library from an eccentric American aunt and, while he dismisses her contribution as trash, he likes the way they fill his bookshelves. I supposed this book to be one of hers. But science, in the form of the doctor, has reduced Freddie to nine and a half fingers. Bone Rites might have some scrap of useful information. Some knowledge from wise women, long for-gotten or suppressed by modern medicine men. I’m too old for magical fairy tales but Cook believes in ghosts and Nanny used to throw spilt salt over her left shoulder to ward off the devil. People believe in the strangest things. Perhaps there is a way, an old way, to repair and reattach a finger. But first, I need the finger. I make a swift decision.

Once the procedure has been completed, the doctor tells Cook he’s going to wash his hands and his instruments. I slide out of the linen cupboard. Freddie is crying in Cook’s lap and she doesn’t notice me. I slip out of the nursery and waylay the Doctor as he emerges from the bathroom.

‘I apologise, Doctor, that my parents weren’t here to greet you.’

‘Oh.’ he says, and my opinion of his brilliance slides a little.

‘I’m glad you agreed with my diagnosis of gangrene. I felt it was important to call you in before the infection spread.’ He blinks at me. I stand taller and lift my chin. ‘Might I offer you a glass of whisky before you leave?’

He follows me down into the drawing room. I feel his uncertainty like a wave behind me. I am young and female, but this is my house and it is a very grand one. I pour the whisky myself to save calling our sticky-beaked butler. I know exactly how to do it – I’ve seen that glass in Father’s hand often enough. When the doctor has sipped at the golden drink and made the ‘tchaaa’ sound that adults always do on such occasions, I put my proposal to him.

‘You may recognise from my mode of speaking that I am a fellow person of science.’ I pause here as the doctor chokes a little on his drink. I wait for him to recover himself and wipe his eyes before I continue. ‘I believe it would greatly help in Freddie’s recovery if he could hold a little funeral for his lost digit. We could make a fingertip-sized grave and say a few words.’ The doctor frowns and opens his mouth, but I speak more quickly so he cannot interrupt me. ‘I am quite certain that this will enable my brother to understand his loss.’ I tilt my head and smile up at him, the same smile Mother uses on Father when she wants something.

‘You are a most peculiar girl,’ he says, but he’s smiling too. He hands over the fingertip. It is very small, about half the size of a hazelnut, wrapped in bloody gauze. I thank him formally, relieve him of his now empty tumbler, and see him to the door.

I place the fingertip in my pocket and go back up to the nursery. Freddie is quiet now – the doctor has given him a draught and he is sleeping. His right hand is a wad of bandages, the thumb of his left hand in his rosebud mouth. Cook is back downstairs. I brush a damp curl from Freddie’s forehead and kiss him softly. Then I fetch my magnifying glass and examine the fingertip. It does not look hopeful. The flesh is loose, black and putrid, the tiny fingernail falls away in my hand. I cannot imagine how I will ever be able to save it. But I must try. I carefully wrap the fingertip in one of my stockings and hide it under a loose floorboard.

Later, when the house is sleeping, I slip from my bed, quietly lift the board, pull out my precious package, and creep down to the library.

CHAPTER 3

1905: Bone Rites

The room is moonlit, silent, just a breath of dusty air wheezing down the chimney. I pull father’s rolling library ladder into place and climb up quickly. Bone Rites is almost as tall as an encyclopaedia, but very thin. Despite that, it feels heavier than the last time I pulled it from the shelf and, strangely, even dustier. I sneeze loudly, drop the book and almost lose my footing on the ladder. I cling to the wooden rungs in fear, certain I will be discovered.

No one comes. I breathe again and climb down the ladder. I rescue the book from the floor and place it on Father’s huge mahogany desk. I light the gas lamp. Fortunately, as I’m not really allowed to use Father’s library, the book seems undamaged by my carelessness. I examine the first page. The text appears to be greeting the reader, but it’s hard to understand. Some of it’s in Latin and it’s hand-written in copperplate. A few of the letters are huge and coloured in, others so small I can barely make them out. I sniff. The book has a peculiar musky odour, like an unwashed body. It feels strange under my fingertips, the pages more like skin than paper. Each page has a heading, I read each one with care, looking for something useful.

A Bone Rite to Defeat thine Enemies

A Bone Rite for the Fynding of Loste Treasures

A Bone Rite for Knowing the Future of a Childe

I blink back tears. What have I been thinking? This is not a book of old ways to heal bones, it’s a made up, magical mumbo jumbo that uses bones. I’m about to give up when I see:

A Bone Rite to Protect thy beloved from Harm.

A line drawing shows a small boy, his arms aloft, protected by a halo of light. I move the gas lamp closer and read the instructions carefully. Then I read them again. It’s not science, as such, but it makes a kind of sense. I return the book to the shelf, move the ladder along, and take down another book.

The Naturalist’s Encyclopaedia is one of my favourite books in Father’s library. Full of detailed drawings and even some colour plates, it details a wonderful array of exotic creatures from all around the world. It also assumes that you, the reader, are attempting to create your own collection and towards the back is a detailed section on how best to preserve specimens. Using this, I have previously attempted to preserve the skeletons of two frogs and a blackbird (with varying degrees of success). It is to this section I now turn.

Ten minutes later, I tiptoe out of the library and slip down the back stairs to the kitchen. I hesitate at the door, thinking of Cook’s fear of ghosts. But when I dare to go inside the room it’s as warm and welcoming as an animal (thanks to Cook’s habit of keeping the range warm all night with a low fire). I stoke the fire and bring a small pan of salted water to a low simmer. Next, I unwrap Freddie’s fingertip, take a small sharp paring knife and strip away as much of the blackened flesh as I can. Then I lower the remains into the pot with a tea strainer. After five minutes of watching it bobbing around, I put the lid on and leave it to simmer.

I allow the fingertip to simmer for another forty-five minutes before carefully removing it from the water with the tea strainer. I cool it slowly under running water and then place it in a clean jam jar filled with a fifty-fifty mixture of laundry soap and bleach. I make sure the lid is tightly sealed before shaking the jar gently. The slowly dissolving soap flakes swirl like snow around the little bone. It’s pretty enough for a dressing table, but I know no one else will think so and the jar is too big to fit below the Nursery floorboard. I shake the jar again, willing the bone to direct me. And it does. I spy the perfect hiding place.

I say nothing to Freddie for four long days. I want to, because he’s grizzly and I long to make him feel better, but I don’t want to raise his hopes for nothing. When the time is right, I rescue the jam jar from the forest of similar jars on the bottom shelf of the pantry. I panic for a moment, pushing aside the legitimate rows of chutney, marmalade and jams until I find my strange little specimen. I examine it. The solution is clear now, the bone gleaming white. I tip the smelly contents down the sink and wash the little bone under running water for about ten minutes, holding on tightly in case the tiny little thing slips from my fingers and disappears down the plug hole forever. Next, having dried the bone on a tea towel, I take a handful of rice from the jar, fill a matchbox with the grains and bury Freddie’s fingertip in their midst. Now all I have to do is wait.

After a week in my bloomer pocket, the matchbox opens to reveal a perfect piece of ivory, roughly the shape of a tiny chess pawn. It’s time to tell Freddie. Fortunately, because Father is away again, I can slip down to the library. I take Bone Rites from the shelf and carry it up to the nursery. Freddie is sitting on the floor, playing with a small wooden train. His right hand is no longer a fist of bandages. Just one length of white gauze is wrapped around his middle and what is left of his index finger. I sit next to him and set the book in front of him. He reaches for it with his right hand, winces and uses his left instead. He opens the book and strokes the first page with his left index finger.

‘Feels funny. Old. What kind of book is it?’

‘A special, magical book.’

He looks up at me in disbelief.

‘Really?’

I turn to the page with the protection spell. Now, in daylight, I can see the illuminated gold circles and triangles drawn around the words. It looks so childish my heart sinks. This is all rubbish – what have I been thinking? But Freddie looks fascinated. I’ve been teaching him how to read and he traces the words with his finger.

‘A bone to… pro… protect… What is this?’

I look at his little upturned face. It’s alight with interest. With hope. With belief. His finger bone is preserved now, I might as well go through with this if it will make him feel better. I smile.

‘It’s a spell to protect you from being hurt.’

His eyes widen and they widen even further when I reach into my pocket and produce the tiny ivory bone. I’m worried he’ll be scared, or angry that I’ve done all this without telling him, but he looks fascinated. He takes the bone in the palm of his hand and lifts it up to the light. I fetch my magnifying glass and he examines the bone closely.

‘This was once a part of me?’

‘Yes.’ I stroke his golden curls and my heart is filled with a complex mixture of love and guilt. ‘And we’re going to use it in the bone rite of protection. We’re going to do a special spell that will stop anything bad happening to you ever again.’

The next full moon we get up a little before midnight. Freddie’s sleepy and rather grumpy. Now it’s actually happening, he’s less sure about what we are doing. So am I, but I put the matchbox containing the bone into my pocket and tuck Bone Rites under my arm. I lead Freddie down the nursery steps, through the stubbornly ghost-free kitchen, and out through the scullery into the garden. It’s cold outside, and once familiar things – hedges, shears, a pile of sacks – are casting strange shadows in the bright moonlight. We follow the mossy path down to the family crypt and, after some considerable effort, push open the heavy wooden door. We go inside. It’s even colder in here – like winter, but not fresh. A bone-chilling cold of damp stone. We’re being quiet, but every sound is muffled into deathly silence. I squash a strong urge to whistle, cough or scream to show I’m alive. It strikes me that a ghost would be far more likely to appear down here than in Cook’s warm, busy kitchen. I light my candle with shaking hands. In its flickering light, I can see that Freddie’s eyes are wide with fear. I must be brave for both of us.

‘Come on, darling. Won’t take long.’

He sits on top of a stone sarcophagus, swinging his little legs. I don’t tell him what must be lying inside it. I crouch down on the stone floor, open a folded piece of paper and tip out the handful of ash I took from the nursery fireplace this morning. It forms a mound, like a tiny volcano. On top of this, I carefully place the tiny bone. It sinks into the soft ash, but the ivory tip can still be seen. Next, I prick my thumb deeply and (after a small struggle) Freddie’s thumb lightly with a silver brooch pin stolen from Mother’s trinket box. Freddie squeaks a little when I squeeze his thumb to produce a few more drops of blood, but he makes no more complaint than that. I mix our bloods in the palm of my hand, and, using my fingertip, draw a small bloody circle around the bone and ash. Then I open the book and read the incantation aloud.

‘Ex virtute amoris et sanguinis et ossuum, te protegam in aeternum.’

As if the book might hear him, Freddie leans forward and whispers in my ear. ‘What is that? French?’

‘No, Latin.’

‘What does it mean?’

‘Shh. I’ll tell you later. Concentrate on the bone.’

We wait. Nothing happens. A fox screams outside and we both jump. Freddie pulls at my plait.

‘Is it done? I’m cold. I want to go back to bed.’

I’m about to answer him when the candle suddenly blows out. We both scream. Freddie lets go of my hair and runs out of the crypt. I grab the bone from the ash pile, scoop up the book and follow him as fast as my legs will carry me.

Freddie falls straight to sleep when we get back to the nursery. I’m exhausted too, but I must return the book to the library before Father gets back tomorrow morning. I’m about to replace the book on the shelf when I decide to take one last look at the instructions.

For the Spelle to wyrke on thy beloved, keepe the Bone close.

I think about this for a moment before the solution comes to me. I shelve the book and go back up to the nursery.

While Freddie snores softly, I snip some gold wire from the back of a picture frame and wrap it around the thicker end of the bone. I attach it to a chain that has, until recently, held a crucifix. I examine myself in the foxed silver of the bathroom mirror. The bone nestles perfectly in the small indent where my clavicle bones meet my sternum. It looks strange, and powerful. I decide I have a holy look, like Joan of Arc. The scientist in me sneers at such superstition, but I remember Freddie’s look of wonder. It can’t hurt to give him hope, can it?

The next day, Freddie falls ten feet from an apple tree. The gardener picks him up and rushes him in to see Cook, but when she examines him, he’s perfect. Not a scratch on him. Cook crosses herself and then clips him round the ear for scaring her. I feel responsible, imagining he fell because he was tired from his night’s exertions. But the truth is far more worrying.

‘I let myself fall to test the magic spell.’ he whispers when we are alone in the nursery. ‘And it worked, didn’t it? It really worked!’

Fear surges through me. Did it work? Or was he just lucky? I’m torn between doubt and faith, but his face is full of such joy I say nothing of that. Instead, I congratulate him and show him the bone charm I’m wearing around my neck.

‘As long as I wear this nothing bad can ever happen to you.’ He flings his arms around me and kisses my cheek. I feel magnificent, but have enough sense to say, ‘But promise you won’t throw yourself out of any more trees? You might wear the magic out…’

He nods, but to tease me he skips to the window and leans as far out as he can.

Soon after that, we get a new, strict Nanny and all our attention is taken up on not getting in her bad books. We don’t speak of the bone rite again and, as Freddie gets older, I wonder if he remembers it at all. Superstitious, I wear the bone charm every day, next to my skin, hidden below the stifling lace collars our militant new Nanny insists upon. Every now and again I put my hand to my throat like her and mutter my incantation. First in Latin, then English: By the power of love and blood and bone, I’ll protect you forever.

Mumbo jumbo or not, Freddie comes to no more harm. He quickly gets used to his reduced index finger. When he’s sent away, first to prep school and then to Harrow, he does well. He’s so popular and good-humoured, no one rags or taunts him. He even makes the first eleven and never drops the ball, despite his loss. He suffers no childhood illnesses, no broken bones, no accidents at all. I am the only one to suffer – I miss him like a limb. I make him save all his baby teeth and I keep them in a Phoenician jar in Father’s library. During the long school terms, I have imaginary conversations with him in the mirror and put a pillow under the covers of his bed so it looks like he’s still sleeping there.

Whenever he comes home, I ask him to teach me things. Algebra and calculus are beyond my feeble governess and her grasp of history is no better than my own. I glean as much as I can from Father’s library and Freddie fills in the gaps. His spelling is atrocious, but he’s a gifted mathematician. As he scribbles equations for me on the page, I see how easily he holds his pen between thumb and middle finger. It’s as if there had never been a pointer in between. My patient has made a perfect recovery, nothing can harm him.

***

The prison skivvy is here. No letter, again, but she has the inevitable bowl of gruel. She never steals so much as a spoonful although she’s so underfed her bones glow sharp beneath the pale shroud of her skin. She’s terrified of me, poor thing. I imagine the wardress told her I was the infamous Vampire of Westminster, the fiend who inspired Arthur Conan Doyle’s story in the Strand Magazine. Such nonsense; I was never interested in drinking blood. Had I the energy, I’d reassure her that I have no interest in her scrawny bones either. All I want is to finish what I started. And a word, a kind word, from Scotland. That – and an acquiescent chaplain – is all I desire.

CHAPTER 4

1912: To Edinburgh

The day I arrive in Edinburgh it’s October – cold, blue and bright. Even the air feels different up here, sharp like a scalpel not soft and muddy like a Sussex spade. I am nineteen, ablaze with energy. As I step down from the train I feel such a sense of release I might fly right up to the castle battlements and perch there like a crow, smoothing my feathers with my beak. I am still dressed in black, at Mother’s insistence, but my case is full of new clothes. Now Father is dead the world is full of possibilities.

Mother made a point of calling me down to the drawing room before I left. She was wearing mourning too, but on her it looked glamourous, dangerous, exciting. She stood by the fire and the light of it glinted in her eyes.

‘But medicine, darling, are you sure? Whoever heard of a female doctor? It’s ridiculous.’

‘There are a few hundred female doctors in Britain already.’

‘You could go to a finishing school in Switzerland, learn how to be a lady. You should’ve been presented at court by now. Pretty girls like you dream of marriage, not study. It simply isn’t done amongst the people we know.’

I folded my arms, watching how the firelight glittered on the diamonds at her throat.

‘The youngest Delacorte girl is studying poetry up at St. Hilda’s.’

She wrinkled her nose prettily.

‘Poetry is a far cry from medicine, darling. And her family aren’t happy about it. They only gave in because she’s one of those strange, bluestocking types. Face like a horse. What else could she do? But you look like me! You could do so well for yourself if you just made a little effort to be civil to your suitors.’

I looked out of the window, wondering why anyone would fight so hard to go to university, only to study poetry. Apart from her native French, and a fascination with Shakespearean tragedies, poetry was certainly all my dreary governess knew how to teach. I enjoyed playing Hamlet to her fey Ophelia, but I’ve never been interested in flowery verse. Daffodils on a hill, wandering lonely as a cloud. Stuff and nonsense. I was interested in bodies, blood, and bones. Realising that Mother was still speaking, I dragged my attention back to her.

‘…and you’re only being allowed to do this because Father is gone, you realise that, don’t you? If he were still alive, there would have been no possibility of you postponing marriage. He valued beauty in a woman, first and foremost.’

She dabbed at her face with a black lace handkerchief. I wondered why she bothered – there were no tears in those beautiful green eyes.

‘I have long been aware of Father’s view of women. He thought hiring my mediocre governess was a waste of money. He never considered sending me to school, let alone university. But he’s dead now and everything is going to change.’

Mother put away her dry handkerchief and gave me a cold look.

‘You will miss your train.’

I moved forward, meaning to hug her perhaps, or kiss her cheek, but she stepped neatly aside and rang the bell for the footman. My throat felt tight.

‘Will you write to me, Mother?’

One of her golden curls had been strategically allowed to free itself from her black lace cap and caress her cheek. She tilted her head on one side and twirled it around her forefinger as she studied me.

‘I shouldn’t think so, darling, do you? What on earth would we say?’

She’s true to her word. The first letter I receive in Edinburgh is from Freddie. It sits on the hall table of my lodgings, glowing in a shaft of sunlight that has managed to penetrate the gloom of the house. I pick it up with trembling fingers. His untidy, slanted handwriting is as familiar as his beautiful face. One of the other girls comes in, bringing with her a wash of icy air from the street. She is almost as tall as me, but curvaceous and dark-haired, her warm hazel eyes bright and vital. She’s as pretty as a bird and greets me with such a warm, impish smile that I want to put her in my pocket.

‘Letter from the parentals?’ she says. Her voice is deeper than I’d expected and has a brightness that suggests she laughs a great deal.

‘Baby brother.’ I manage to say with a thick voice.

‘No chance of a postal order then! Shame. If he’s anything like one of my squits, he’ll want you to send him something.’

I force a laugh and make my escape. My room is smaller than one of the maid’s rooms at home and almost as drab, but it’s all mine and I love it. My landlady, Mrs Glennis, does not include cleaning in her ten-shilling fee, so no one comes in here apart from me. It is the most beautiful luxury to know that if I leave my stockings on the floor, my pen on the desk, a cup on the windowsill, they will remain there until I choose to pick them up. There’s a pile of books on my chair, so I sit on the bed. The springs groan companionably as I open my letter.

Dear Sis,

How’s Scotland? Have you eatern haggis yet? Can you find out if it is really made of sheep guts – Johnson A. says it isn’t, but I say it is. Please don’t send any though. I would like a tin of Callard and Bowser butterscotch. Mater is too busy to send tuck.

Your loving bother,

Freddie

I read it several times, laugh, cry, and vow to send him a huge tuck box full of treats. Dear Freddie, he was already at Harrow when Father died. My only emotion at the funeral was how nice it was to see my brother during term time. He did cry a little, even though he’s thirteen now, but I suspect it was more because he felt that one of us should. Or perhaps he was genuinely sad. He’s a demonstrative boy and – unlike Mother – Father did show a kind of proprietary interest in his only heir. He certainly cared little for anyone else. The service was poorly attended, and no one came back to the house. It was a warm, sunny day. Mother went out to see a friend, and Freddie and I spent a lovely afternoon playing croquet on the back lawn. I didn’t cry until Freddie returned to school the next day.