Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Cinnamon Press

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

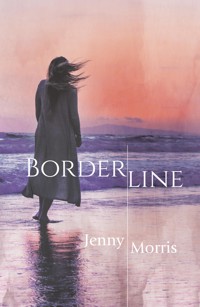

When artist, Eve, leaves London to live alone where no one knows her in small-town Shipden on the north Norfolk coast, little does she suspect that the next eighteen months will change everything. As she writes to and receives emails from her travelling daughter, Jez, Eve's story unfolds, filtered through her particular perspective, while around her, in the old house converted to flats, strange characters inhabit her new life. People like Hester, the eccentric widow of a once well-known journalist and Amos, a troubled man searching for a wife. But the quiet life is not what it seems. Eve's relationship with a local poet, Choker is disturbed when Leo, an actor from her past, finds her. When ex-military-man, Knox, moves in to the house as others leave, her new sense of home is under question. And even in this secluded place, there are those who know more about Eve than she knows herself, like the two old Russian sculptors who can tell her about her unknown father. Inhabiting this fragile borderline, will Eve be able to make a new life fostering unwanted and troubled children? Will hope win the day in this story of secrets, death, grief, and the bonds that tie mother and daughter? A compelling debut novel from poet and artist, Jenny Morris.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 278

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Contents

Title page

Copyright

Half title page

Dedication

March

April

May

June

July

August

September

October

November

December

January

February

March

April

May

June

July

August

September

October

Borderline

Jenny Morris

Published by Leaf by Leaf an imprint of Cinnamon Press,

Office 49019, PO Box 15113, Birmingham, B2 2NJ

www.cinnonpress.com

The right of Andrew Dutton to be identified as author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patent Act, 1988. © 2021, Andrew Dutton

Print ISBN 978-1-78864-929-2

Ebook ISBN 978-1-78864-948-3

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data. A CIP record for this book can be obtained from the British Library.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior written permission of the publishers. This book may not be lent, hired out, resold or otherwise disposed of by way of trade in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published, without the prior consent of the publishers.

Designed and typeset by Cinnamon Press.

Cover design by Adam Craig © Adam Craig.

Cinnamon Press is represented by Inpress.

Borderline

For Josephine and Jeremy, with thanks

March

Eve had been given away as a child.

She thought about that every time she saw or heard a baby. And that day in March a child was crying nearby. A long drawn out, hopeless wail that caused her to stand still, listening.

In the large Victorian house, the main entrance door slammed. Curious, being new, she went to her window. A hugely fat man came out and shuffled across the parking area towards the street. He was bald and wore tight beige jogging trousers and a sweat top. From her turret she saw him as a series of slowly progressing, bulging circles. When he turned to pause at the wall, she could see just how short he was. He coughed. Now she knew he must be the one who lived on the floor under hers, the one who climbed the shabby stairs so laboriously and wheezed so much.

Somewhere in the house the child stopped crying.

In the silence someone rang the bell on her internal front door.

She glanced at the mirror. Her light hair hung in tangles round her shoulders, her jeans covered in paint stains and her feet bare. She pulled a demented face, not wanting to see anyone, wondering if she could pretend not to be in.

Her bell chimed again.

She’d learned in a few days that in this converted old house the walls of the flats were thin. Neighbours could tell who was at home. She didn’t want to offend anyone yet.

She opened the door.

The tall figure on the landing blocked out the light. ‘How do you do? I’m Hester Monkman. Welcome to Strand House.’ She wore a black, wide brimmed hat over her black dyed, cobweb profusion of hair. A dark coat dropped from shoulders to doormat. Hooded, sharp eyes and a narrow, high-bridged nose gave her the look of an eagle. A thrust-out hand gripped Eve’s fiercely.

She winced and stepped back. ‘Hello, I’m Eve Key. Do come in. I’m afraid it’s a bit of a mess.’ She caught an odour of whisky and nicotine. ‘Coffee? I’ve just made some.’

‘Ah,’ with a glance round, ‘you don’t know what serious mess is.’ Hester’s face, a slightly crumpled parchment, trembled. ‘Black for me.’

While Eve fiddled with the brewed coffee she tried not to stare at her guest. Hester stepped round the small apartment with the air of a sergeant-major on inspection. The outcome was favourable. ‘You’ve done wonders. The couple who lived here before were anoraks into twitching, spent their time lying in mud on the marshes. They liked the colour of sludge.’

‘Yes, some walls took four coats of white paint to cover it.’

Hester picked her way round a pile of boxes. She took a cigarette packet from her pocket, looked at it, sighed, then put it away again.

Eve didn’t say anything. She poured coffee into a mug. ‘Which part of the house do you live in?’

‘Ground floor. Number one. By the front door. It’s useful for the dogs.’

Eve hadn’t heard any dogs, but there were a couple of cats in the house. They lurked on the stairs and were easy to fall over in the gloom. ‘I thought the lease said no pets.’

‘Ah, that.’ Hester breathed in heavily. ‘As long as everyone is agreeable, animals are fine. I couldn’t live without my labradors. They love the beach.’

Eve thought of small children playing in the sand among dog mess.

Hester stuck out her bottom lip and shot imaginary smoke towards the ceiling. ‘Sadly, from the beginning of May until September they’re banned on the nearest beaches, poor darlings. So then we have to go further afield. But they’ve just had a marvellous fortnight on the moors, running around all day. I’m only just back from visiting my son. Otherwise, I’d have called on you earlier. I spend most of my time out with the dogs. Or writing. I’ve been a widow for years.’ She grinned, exposing crooked yellow teeth. ‘You may have heard of my late husband, the writer, journalist and soak. He was big in Soho. The drink got him. Liver shot to pieces. I’m writing about him. My Life With Hugo. It’s been on the go for ages. I can’t decide what to put in and leave out. If I don’t finish soon everyone will have forgotten about him. He covered wars, famines, met celebrities. We had many bizarre nights.’

She looked at Eve.

The young woman had the feeling that she was about to be quizzed on her own life and wanted to forestall that. ‘Who lives directly below me?’

‘Number four? That’s Amos Postle, short and fat. Born in this town, works in the little ironmonger on the High Street. Shy. A bit deaf. Sensitive about his size. He’s been looking for a wife for as long as I’ve known him. Does internet dating, goes off on mysterious assignations.’

‘I’ve met the man adjacent to me on this landing. Number six. The one with the bleached busby hairdo, Darren.’ He was tall and emaciated and ran lightly up all the flights of stairs making scarcely a sound. ‘What does he do?’

‘Not much. Drugs, sometimes, I fancy. He does work at the crab factory on and off.’

‘He seems to be out at night a good bit.’

‘Goes to the club by the bus station like all the youngsters round here I expect. There’s not much else.’ Hester reached out to the windowsill and picked up the framed photograph of a young girl in school uniform. ‘Nice eyes, very white shirt. Who’s this?’

‘My daughter, Jez.’

‘Is she going to school here?’

‘No. That was taken a while ago. She’s not with me.’ Eve put her hand out for the photo and carefully replaced it.

‘Where is she then?’

‘Round the world trip. Backpacking.’

‘With a friend?’

There was a silence.

‘No.’ Do shut up, woman, thought Eve.

‘That’s brave. But I did something similar myself in my teens.’ Hester rubbed her grubby fingers. ‘Dancing with danger… But I must go and unpack the old Morris Traveller. It’s a treasure, an antique. I’m absolutely petrified it will give up the ghost soon. I pray for it, nightly.’ She drank down the remains of her hot coffee and pushed her shoulders back. ‘Splendid to meet you, Eve. Vast improvement on the boring bird lovers. And thank you for the coffee. Can’t stand the instant muck. You must come to my little get together tomorrow night. Drinks at eight?’ She smiled and left in a hurry.

As Eve watched the top of the black fedora lurch downstairs, Darren came running up, his silver earrings glinting.

‘Awright, mate?’ His smile was lopsided and genuine.

‘Fine. You?’

‘Great.’ He dashed into his flat leaving the door ajar.

All the time Eve had been in Strand House, Darren’s front door had been left open displaying a pile of magazines and dirty washing.

As she pulled her own door to and the Yale lock clicked, she heard the rhythmic, relentless boom of heavy metal on the other side of the wall.

Would Jez like that music now?

Since Eve’s move from London, she’d so much to do. Her new part-time job due to start after Easter needed organisation. But she missed her daughter.

Picking up the photo taken nine years earlier, she sighed at the familiar depiction of that clear, ingenuous gaze. Now Jez was lost to her mother.

A mother can’t be with her children forever, Eve thought, can’t always be there urging them to eat properly and not go too near the edge with drugs or alcohol or chancy partners. You just let them go and hope. At a young age Eve herself had wandered near the edge often. She shuddered. That was the trouble, the unstoppable risk-taking and craziness of youth.

Jez was short for Jezebel, a name chosen by the pagan, teenage Eve for her daughter as soon as she’d set eyes on her, dark haired and red faced, waving her fists in a London labour room. A female of spirit, decided Eve. She had always secretly admired that scheming, shameless Jezebel since first reading about her in school. And anyway, there was no one to deny her that choice.

But the little girl turned out to be a most gentle child, kind and obedient, a fish-eating vegetarian at eight and one who certainly didn’t care for her name.

‘I’m Jez. That’s short for Jessica,’ she explained firmly on the first day at her secondary school, and told her mother later. There she conformed to the rules and, at weekends, joined the local church choir and organised Harvest Festival hampers for the old people of the parish. She was never timid, but always curious about other people and different ways of life.

Eve felt guilty at the choice of name for her only child and every time she recalled the black ink inscribed on the birth certificate, twisted her mouth and groaned. Poor Jez. Somehow her name must protect her from all dangers.

And now she was so far, so lost to her. Eve stared at a single, fat, red tulip in a glass vase on the mantelpiece. She’d found it in the park, snapped off in the wind. It’s closed up like a heart, she thought, like mine, cool and still. It’s just a lost thing, something that exists and then dies and decays. And who’s to know or care?

She stood at the dormer window and looked out at the sea. Beyond the rooftops it stretched in shadowed bars, glistening in places where the sunlight filtered through clouds. The white flecks on the waves were reflected in a hail of blossom, torn early from the trees, which flurried up against the glass to be swept away.

A scent of salt was suspended inside the attic room. It was cold.

Her decision had been swift. She chose to move to a small town on the North Norfolk coast because she had never been there and accommodation was cheap. Her escape. After selling her London studio flat there was enough money to buy something similar in Shipden, enough for a year’s travelling with some left over to allow Eve to live without full-time teaching. A great bonus, allowing her to paint.

The north light in the living room was ideal. The newly painted white walls shone with reflected radiance from sea and sky. At the top of the old house, the past servants’ quarters, her windows faced in three directions. The views had persuaded her to buy the flat: to the east, the avenue and other divided mansions set in tended gardens, and at night, the rhythmical beam of the lighthouse, to the north the sea beyond the park and boating pond, and to the west the first shops and restaurants and the massive church tower rising above rooftops and chimneys.

She thought the town quaint with its elegant Georgian and Victorian terraces, its terracotta facades and odd domes, its flint stone fishermen’s cottages, and its old-fashioned little butchers and sweet shops where everyone spoke politely and parcelled up purchases neatly. The pace was reassuringly slow. This must be a good, safe place in which to live.

Touching the cold red tulip in passing, she went to her computer. There was an e-mail from Jez. As the words appeared on the screen she smiled.

Mum. Are you settled? I logged on this morning for the first time in seven days and have heaps of messages, which is good as I have spent the last night in the most squalid, vile place you have ever seen in your life. It was the cheapest of course. The complete and absolute pits and as it was my first night in Singapore, I am trying hard not to let it put me off the city. The room was filthy and the ceiling falling in. The water from the basin ran straight out into a bucket underneath. The cockroaches were gigantic. I left at 5am past the snoring Chinese man at the bar. Otherwise, the city is great. It’s really clean and you can’t chew gum or eat in the streets. I’m enjoying ambling around and eating strange food in the hawkers’ stalls. I like the Indian doughy bread and some big spiky fruit I don’t know the name of. There are all sorts of exciting dishes such as Pigs’ Organ Soup and Chicken Feet With Noodle, which I am avoiding, but I accidentally ate some sort of animal thing last week in Bali which sorted out my constipation problem. You will be pleased to know that I am cleaning and flossing my teeth regularly as I can’t bear the thought of being in the middle of nowhere with toothache. Lots of love Sweaty Jez with mozzie bites xxx

Eve tapped out a response:

Jez. This place is great. The sea air makes everything look clean and sparkling. It’s amazing after dirty old London. I haven’t had a chance to start my own artworks yet, I’m still sorting out painting walls and enjoying myself arranging stuff. Am sleeping better here than I’ve done for years. My neighbours are odd. There’s Amos, a strange little fat man living below who’s like a troll in a fairy tale, and below him an oldish woman called Hester who’s a kind witch. I’m growing my hair really long to hang out of my turret window for the handsome prince to climb up, eventually. I’ve had fish and chips every night since I moved here. Can’t get enough. Mm. Glad to know that you’re taking care of yourself. Lots of love, M.

She needed to buy food, and so went out to explore further.

The breeze rushed from the North Sea. She recalled a London friend telling her how the weather tended to be ‘bracing’ in Norfolk. I need to be braced, she thought, wishing she’d put a jacket on, and walking faster.

Newly painted shop windows were full of Easter eggs and paper flowers.

People smiled at her in passing. Some strangers even greeted her. One can’t be inconspicuous and anonymous in a small town, she mused, I’m too used to city living.

In a newsagent’s, she read the headlines about a girl who’d disappeared on her way home from school in a city suburb. There were pictures, the girl smiling, in her uniform. Innocent eyes, short hair, a rumpled white collar. There was something about that dishevelled choirboy collar that made Eve sick.

Eve imagined the worst of what might have happened and what her family was going through. In her head she saw an area cordoned by police tape. She stumbled as she meandered along narrow pavements, passing strangers, stepping off into the street, nearly getting knocked over by a van. She headed for the sea, shivering.

Under a washed-out sky, electricians hung coloured lights along the front as rusty tractors dragged two-man crab boats on hawsers over the sand and shingle.

She stopped to watch the boxes of shellfish being unloaded, then went along the pier where a man with a thermos guarded fishing lines. The café-bar and little theatre at the end were being renovated for holidaymakers. Everything was waiting for the action.

The next evening at half past eight Eve, wearing a red dress and carrying daffodils, walked down the wide flights of stairs in Strand House. Going by various doors, one marked ‘A. Postle’ in faint pencil letters, she knocked on the white entrance of number one.

As the door opened a noise of conversation and a smell of smoke and dogs hit her. She held the flowers to her nose before offering them to Hester, who, encased in black, ushered her into the living room.

‘Everyone, this is the new occupant of number seven. Do welcome Eve!’ Hester turned to a table of bottles and an old lady leaning on a stick. ‘Bloody Mary.’

Eve wasn’t sure whether this was an introduction or a drink suggestion. ‘Mm.’

She accepted a huge glass of what turned out to be mostly vodka.

‘Baskets, boys!’ Hester pointed. Two dark and shiny dogs were sniffing about, waving their tails and knocking over small china objects. They padded with reluctance into the kitchen.

The sparse-haired lady with bright, knowing eyes peered over her spectacles. ‘Pleased to meet you, Eve. I’m Grace Tombling and that’s my husband, Vernon, in the corner. We’re at number two across the hall.’ She fumbled with her stick, a glass of sherry—rivulets sliding down the outside—and an outsize handbag. ‘So difficult to manage.’

Eve helped her into a chair next to a windowsill adorned with pots of primulas. ‘The garden is lovely here.’

Grace beamed. ‘I’m so glad you like it. Vernon and I do all the gardening at Strand House. We’re very particular. Some plants don’t do well by the sea, but the earth is rich. The roses are beautiful in summer and the hollyhocks. He cuts the little bit of grass and the hedges, but he doesn’t have as much spare time as me. I only help in the charity shop by the church, but he works for people with learning difficulties. He just can’t retire.’

Eve stared at the sprightly figure of Vernon, amiable and bloodhound-jowled, who vigorously handed round crisps.

‘Aha. This must be the new resident.’ A faint foreign accent. Authoritative voice.

She turned as a tall, bone-thin man put his arm round her shoulder.

In a leather jacket and jeans, with long, black, untidy hair and dark stubble, he appeared self-assured, with deep-set eyes scrutinising her from head to toe, well-defined Pharaoh lips in a sensual curve. ‘I’m Choker.’ He extended his hand.

‘Something Choker? Or Choker something?’

‘Neither. It stands alone.’

‘Do you live in this house, too?’

‘No. My place is the other side of town. But I’m often here, visiting Hester. Mine’s the motorbike round the side.’ He looked down her front. ‘I like your frock. Very pleasant.’

She pulled up the low-cut bodice slightly and gulped her drink.

‘What do you do, Eve, tempt?’

‘Not at all,’ coldly. ‘I teach art history.’ She told him about the part-time job she’d been offered at the city college.

‘How will you get there?’

‘By train. They seem to run frequently.’

‘Not often enough, you’ll find.’ He refilled his whisky glass. ‘I used to teach. Given it up now, thank God.’

‘Choker’s a poet,’ said Hester, in passing. ‘He has several slim volumes.’ She paused. ‘And you know what poets are like. They have triple compulsions—getting published, getting drunk, and having sex.’ She patted his cheek.

In the silence that followed Eve stared at the floor. ‘What things, er, what do you write about?’ she asked.

‘Someone once said that there are only three subjects for poems: love, death and time. I prefer death.’

At that word she thought again of the missing girl whose parents she’d seen on television appealing for information. Why hadn’t the girl come home? Eve thought about Jez. Her eyes blurred. ‘Excuse me.’ She walked across the room.

The walls had built-in bookcases from floor to ceiling. They contained mostly old books, gilded and soft coloured. Eve pretended to study one and blew her nose. She looked around. The ceiling was stained with nicotine and the long curtains were a faded crimson brocade. Intricately patterned cotton nets had turned bone coloured in years of sunlight. A large, worn, Persian rug covered the floorboards and little mahogany tables were littered with porcelain animals and pot-pourri dishes.

Amos had squashed himself on a sofa next to a girl with an infant. He quivered, red and perspiring, ill at ease. ‘What?’ he kept shouting to the girl. His voice, high-pitched, belonged to a different person.

Eve introduced herself.

He didn’t look her in the eye. ‘I saw you move in. Lots of pictures.’ He struggled to rise. ‘I’m just now going,’ he said. ‘Got to go.’

He stood less than five feet tall, but bulky. As he tipped his head back in his effort to get away, the hugeness of his nostrils showed. She noted the plump apples of his cheeks, the sparseness of eyebrows and lashes, the almost lipless mouth, the comparative smallness of his hands and feet, and a scent of mildew clinging to his clothes. He was, she felt, afraid of her.

As he bulldozed to the door, she sat in the unpleasantly warm seat he’d vacated.

‘Cheers,’ said the girl with waist length copper hair in braids. She crossed her long, bare legs, one with a tattoo of a butterfly on the ankle. ‘I’m Cheryl and this is my Troy. He’s eighteen months. Don’t talk yet but he been running around since he was ten months.’

This must be the child I heard, thought Eve.

Troy lay propped against a cushion, almost asleep, a dummy plugging his mouth. He looked a sturdy boy, his dark hair shaven to the top of his ears. His eyelids flickered and closed.

Cheryl pricked his cheek with a purple talon. ‘At least you int going to be a nuisance.’ She turned to Eve. ‘He don’t sleep a lot, usually.’ She seemed annoyed he’d chosen that time for a nap.

Eve had noticed his buggy in the hall earlier. ‘Which flat do you live in?’

‘Five.’

‘That’s the first floor, isn’t it?’

‘Yes. Above them moaning old Tomblings. They’re always complaining about Troy. He have a little car he sit in and they say it make noise on the floorboards. Poor kid’s got to play somewhere. They don’t like my music either.’ She gave a hoarse bark of laughter. ‘I don’t give a stuff.’

‘My daughter would probably like your music. She’s about your age.’

‘She got any kids?’

‘No. She’s travelling at the moment.’

‘Will she come here after? To Shipden?’

‘I’m not sure. For a while perhaps.’

‘She’ll bloody hate it. It’s dead boring here. Nothing to do. I bin here all my life. Three pubs worth going to. That’s it.’

‘The town must be busier in the summer, with holidaymakers?’

‘Bit livelier.’

‘Where would you like to live?’

Cheryl turned to her and frowned. ‘I int moving. I go up my Mum’s and dump Troy on her if I want to have a good time.’ She tossed her braids back. ‘It’s convenient.’ She pulled Troy’s dummy out and thrust it in her pocket. The child never stirred. ‘Where d’you come from?’

‘London. Excuse me,’ Eve smiled, got up and went to talk to Hester who refilled glasses without stopping. Already Eve’s ability to focus and concentrate was failing.

‘Do you have any more family, apart from your daughter?’ Hester asked.

Eve pretended not to hear and downed her third glassful.

But Hester just repeated herself.

‘No,’ Eve mumbled and crossed the room again.

Another strange old couple with matching thatches of swept-back thick white hair looked up and raised their glasses to her. She grinned back.

‘Hi, gorgeous.’ Choker stared down his scimitar nose. ‘Come and sit here and tell me all about yourself.’

Eve, unwilling to be questioned, shook her head, made her apologies to Hester and left at the same time as the Tomblings. She carefully negotiated the stairs, clutching the banisters.

In her flat she drank a half a litre of water and crept to bed.

A motorbike raced up the hill past the house with an ugly howl. Then silence again.

Below, through the floorboards, she could hear the feminine tones of Amos. She couldn’t make out his words, but he sounded excited, then angry. He must be on the phone, she thought, there was no response to his monologue. Eventually he appeared to be sobbing. Then there was quiet again. She was uneasy.

Thinking of Jez, she remembered how adventurous she was as a little girl, how she ran ahead through forests, or sand dunes, or winding lanes. She visualised those small legs trotting in front of her. At last, she drifted off to sleep.

When she woke, the pain in her skull was powerful. Serve me right, she thought, no one forced me to drink so much.

Light streamed through a gap in the curtains. Gulls called above. She stood carefully and went to walk on the beach until she felt better. Shipden meant reassurance, she decided, it had something to do with the same salty smell of seaside holidays.

Back in the flat she decided to spend the day painting her bathroom yellow and white. She turned on her portable radio and balanced it against the basin, but was thinking about Jez and not really listening to Radio Four until a familiar voice with a slight foreign accent caught her attention. It was a recording of Choker, reviewing a young man’s first collection of poems. He damned with the faintest possible praise and read a sonnet in a loud, sarcastic tone. This so annoyed Eve that she turned the radio off. Then, minutes later, she put it on again as she remembered she wanted to hear his full name. It was too late, the programme had ended.

She was on her knees working on the skirting board when she heard a presenter say, ‘Two hundred and ten thousand people are reported missing every year in this country. One in three are never seen again.’ She imagined the poor relatives waiting in fear for news. And those lost young girls disappearing without trace.

She put down her brush, changed her clothes and went out again.

Walking through the town she came across a little Viennese style café, its windows steamed up against the cool air.

Inside it was warm and full of the aroma of chocolate and coffee. The thick floral carpet, well-upholstered banquette seats, blue and white wall tiles and faint violin waltz music appealed. Not only were there framed posters of plates of pastries and cream-laden cakes, but also what looked like the real thing in a revolving display cabinet. She liked the slow ceiling fans, sluggishly stirring the warm air, she admired the carved cuckoo clock which told the wrong time, and she especially liked the girl waitresses in their lace-trimmed dirndl skirts.

From her corner table she watched as elderly ladies in pleated skirts and cardigans pressed invisible cake crumbs to their lips and stirred sugar with tinkling spoons in china cups. Two wore the sort of hats that were fashionable fifty years earlier.

Middle-aged coast walkers in solid boots and thick pullovers chomped more substantial food. Their faces shone, weather-beaten and enthusiastic, their eyes gleamed above steaming fish pies.

With eyes hidden behind narrow dark glasses, two young men in worn black leather drank wine and consulted bits of paper pulled from wallets. They spoke an Eastern European language unfamiliar to Eve.

Like Cheryl, the waitresses were barelegged. It must be a Norfolk thing, she thought, after a while a girl’s mottled, naked legs must become weathered and impervious to the blasting cold wind.

Relaxed, she drank her coffee. It felt good to be looked after, to have attention from someone; she was very conscious of being alone. There was nobody to notice what she did here, in Shipden, nobody to care.

‘Everything all right?’ The waitress in the short-sleeved white blouse grinned at her as she swept crumbs from the next table. Her hands and arms were soft and pale.

As Eve nodded, her mobile rang loudly. It seemed incongruous there. An offensive noise issuing from inside her bag. She’d neither realised it was switched on, nor intended it to be. People turned to stare. Was this an emergency?

‘Hello,’ she said, cautiously.

‘Is that you, Eve? I’m just back from a tour in the States. I must talk to you. Where are you?’ The voice was low and urgent.

‘Leo. I can’t speak now. Ring me later.’ As she snapped the phone off, her hand trembled.

She paid the bill and went out into the hostile wind again. Making straight for the sea front she stopped at the first litterbin, half full of greasy chip papers. She pulled her phone from her bag and chucked it straight in. It fell with a clatter to lie unseen under the rubbish. She walked away.

That’s it, she thought. I don’t ever have to speak to Leo again. I don’t need a mobile phone. The few people I want to talk to have my new phone number at the flat. I don’t need to think about Leo.

But she couldn’t help it.

She’d known him for a long time. He worked as an actor, but more often was ‘resting’ or in a series of temporary jobs, sometimes as a film extra. In the past few years, he’d earned substantial sums at an escort agency. He was her age, late thirties, and very conscious of his attractiveness and the relentless dance of time leaving its, so far, slight marks on his appearance. ‘That Leo’s a vain bloke,’ said Eve’s friends, laughing at him.

‘My face is my fortune,’ he always said, ‘and my body. I must be desirable if I’m going to break into films.’ But his big breaks were slow in coming and he spent a lot of time scrounging from his friends, Eve included.

She managed to put him to the back of her mind, then recalled her phone.

What if someone found and used it? The cost to her account might be horrendous. And the mobile had been expensive enough in the first place. And her personal information, new work number and contacts were on it. What was she doing, throwing it away? She should bin Leo, not her phone.

She ran back and retrieved it.

At home she logged on to see if Jez had emailed.

Mum, I’m in Melaka now and really enjoying it. Everything’s cheap, it only cost me £4 to travel on the bus from Singapore and the bus fare to Kuala Lumpur is £1.50 or thereabouts. I’ll go in a day or two. I’m in a very basic hotel, really cheap but ten times better than a backpackers’ hostel with crappy old mixed sex dorms and putrid showers. I got sick of those in Australia and New Zealand. I’m very happy and putting on tons of weight, ballooning into a huge bloaty whale person eating too many noodles and doughy pratas. In one of the Malaysian food halls today I decided on a seafood stall and chose my mysterious and suspicious bits of fish, and the lady cooked them for me in a laksa noodle dish, quite spicy. I always eat with the locals and have grown used to eating with chopsticks now. Must go, my eardrums are on the verge of exploding. I’m in a noisy cybercafé full of Malaysian kids playing a loud internet game that involves screaming and blasts going off and booms and explosions and every now and then they all leap up and run around and swap computers for some odd reason. Lots of love Bloaty Noodle Eater xxx

Jez. Glad you’re eating well. You must look after yourself. I’m having a great time, settling in. There are a couple of young people your age living in this house, so it’s quite lively. I’m trying to sort myself out ready to start teaching. Reading my old textbooks is making me anxious. But I’ll be fine. You know me. I’ll be on top of things in no time. And it’ll be fun going on the train, much better than being stuck in the tube under the earth. This is a healthy life. Miss you. Love M.

She thought again about Leo. Thankfully he didn’t know where she was. She’d keep her mobile off. She didn’t want his calls and texts. Why couldn’t people just leave her alone?

April

Easter had been and gone. The weather improved. Weeks earlier, Eve had filled in her CRB application form and been cleared to work with children and youngsters. She became used to her new job.