Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The O'Brien Press

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

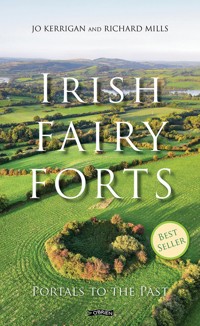

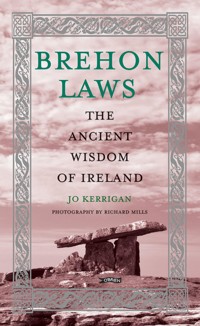

A fascinating look at the lifestyle and values of ancient Ireland Thousands of years ago, Celtic Ireland was a land of tribes and warriors; but a widely accepted, sophisticated and surprisingly enlightened legal system kept society running smoothly. The brehons were the keepers of these laws, which dealt with every aspect of life: land disputes; recompense for theft or violence; marriage and divorce processes; the care of trees and animals. Transmitted orally from ancient times, the laws were transcribed by monks around the fifth century, and what survived was translated by nineteenth-century scholars. Jo Kerrigan has immersed herself in these texts, revealing fascinating details that are inspiring for our world today. With atmospheric photographs by Richard Mills, an accessible introduction to a hidden gem of Irish heritage

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 156

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2020

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

BREHON LAWS

THE ANCIENT WISDOM OF IRELAND

JO KERRIGAN

PHOTOGRAPHY BY RICHARD MILLS

4

Contents

8

A rare fragment, reproduced in Ancient Laws of Ireland Vol III (1873).

Introduction

Back in prehistory, long before anywhere else in northern Europe even started to think about assembling basic laws for their country, Ireland possessed a smoothly working, humane, practical, thoughtful and incredibly detailed code of lawful behaviour. Even today, a couple of thousand years on, we are only putting back into place principles that were taken for granted by our furthest ancestors.

Irish wives, to take just one example, had a right to their own property millennia before the Married Women’s Property Act of 1870. An offender’s state of mind was always taken into consideration when imposing punishment. Questioning whether someone had any business being in the place where he claimed to have been injured was automatic. Simple and easy divorce by agreement, restitution for property stolen, compensation for slander and libel, were all covered. Caring for the environment, protecting trees and looking after animals, birds and bees with love and attention was all-important. The death penalty, enforced so brutally and frequently elsewhere, 10was only ever imposed in the most extreme of circumstances. The briefest study of the Fenechus, or brehon laws as they came to be known (from breitheamh, a judge), reveals the amazing scope and thoughtfulness of this legal system. It was developed and used to promote fairness, justice and widespread peace. Cruelty, savage reprisals and revenge form no part of Ireland’s early laws.

Our position on the westernmost edge of the then-known world was key to the growth and survival of Ireland’s ancient laws. This remote location meant that we avoided the early waves of invaders that swept across countries further to the east. Rome never sent legions to conquer us, as it did neighbouring England and France. As a result, our culture remained untouched, entirely home-grown. It evolved, from the people by the people for the people, and laws that grew and became established through thousands of years remained virtually unchanged. You couldn’t say that of anywhere else in Europe.

Of course, it couldn’t last. When progress (if you can call it that) brought the outside world to Ireland’s shores, violent change was inevitable. It is a rule of thumb for invading colonists to extinguish any existing language, literature, customs and traditions. Only by doing this can they be sure of success. If you remove a subject country’s entire culture, you can then impose your own, and rule them all the more easily. A conquered people must be forced to accept that the new ways are the only acceptable ones, that the foreign tongue and foreign customs are the only road to success, indeed survival.

That’s what happened to Ireland eventually. It was inevitable. We couldn’t hope to stay safely on the perimeter for ever, 11after all. Christianity came first, imposing its own changes, followed by the Vikings, who established seaports and trading cities. Then came the Normans. All of these had some effect on our native laws, but not as much as they might have done. It took the particularly determined strength of the Elizabethans to force change, destroy old records, and drive brehon law into the depths of history, where it was eventually all but forgotten.

Not quite, though.

When Ireland gained some small degree of freedom from the oppressive penal laws in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, some of the ancient manuscripts and documents that had survived slowly began to surface. These were gradually collected, and the long, slow task of deciphering them began. It was to prove a challenging task. After all, the Irish language had been outlawed for many years. It was no longer written and spoken as it had once been. To add to the difficulties, the sources that had survived were written in a far older form of the language, the use and knowledge of which had disappeared with the last of the brehons under Elizabethan rule. To the surviving texts (themselves copies of copies) had been added, at different times, hand-written notes, glosses and comments, in different, later versions of Irish.

Some academics were of the view that these ancient documents were untranslatable, their content lost forever. Others disagreed and persevered. The task is still going on today, and will continue for a long time to come. Having lost so much doesn’t help with the work on what was saved or rediscovered. Even now, when what has been brought to light is pored over, 12experts disagree about correct interpretation. Conclusions must, perforce, be conjectural in many cases. The meaning of some archaic terms may stay obstinately untranslatable.

But there could well be texts still hidden, waiting to be found, perhaps in the binding of later books, squirrelled away in old libraries, tucked safely into the walls of castles (this was how the Book of Lismore was rediscovered), or even buried in bogland. As recently as March 2019, the Avicenna Fragment, part of a fifteenth-century Irish translation of a tenth-century Persian medical treatise, was found in the spine of a later text. Indeed, some great institutions – the Bodleian in Oxford, for example – employ experts to check book bindings for unsuspected hidden documents. More light is gradually being thrown upon this most wonderful resource. And the laws that were lost – are they still out there somewhere, waiting to be rediscovered?

In the meantime, this short book is intended to give an introduction, some brief idea of the incredible heritage we possess in the brehon laws. Every single person of Irish descent should be immensely proud of them. While other countries of ancient Europe swirled in confusion, Ireland held steady and calm, possessor of a unique legal system that anticipated by thousands of years much of the enlightenment we consider to be a modern achievement. All that time ago, we led the way.

CHAPTER ONE

A Brief History

The brehon laws are very old indeed, dating from long before the coming of the Celts. Certainly some of the laws relating to women appear to stem from that earlier culture. Their origin may be concealed within the legends of the golden people, the Tuatha de Danaan. They are said to have inhabited Ireland before the militant Celts, arriving from Spain, drove them into the magical underground world they are said still to inhabit today. Most legends have some basis in sound fact, and the predecessors of the Celts – tall, fair-haired, lovers of music and the arts – certainly existed, even if they were not quite the fairy folk we have made them.

The oldest traditions hold that the laws were first collected into one body by a great judge, Ollamh Fodhla, somewhere between 700 and 1000 years BC. Collected, not invented. Fodhla gathered together what had already been developed over a very long time. (The world ollamh is still in use in modern Irish, denoting ‘professor’ or ‘very learned person’. In ancient Irish it was used both for judges and senior poets.) 1415

A hilltop meeting place.

Strictly speaking, this collection of laws should be called the Fenechus, or the laws of the Feini, the land-tillers, or common people. That is the key to the whole concept – legislation and regulation of everyday life, evolving from actual events and occurrences, and carried down from generation to generation as a true expression of natural justice. The Irish word for judge is breitheamh, and so these regulations became familiarly known as the brehon laws. 17

It should be noted from the beginning, however, that the brehons did not actually mete out justice. They studied the particular circumstances of a grievance and pronounced what fine, reparation or restitution was due. The community within which the offence had occurred would see that justice was done.

THE PLACE OF MEETING

Judgements were given at known gathering places, so that everyone who wanted to could attend: for example, on a high hill that could easily be spotted from a distance for those travelling from afar; at one of the ancient monuments or stone circles known since time immemorial; or under a special sacred tree within a community. The important thing was that the occasion should be seen to be open to all, as befitted a law system of the people. As kingdoms developed, these events often took place during fairs or other state occasions, the ruler and his chief brehon attending to see that justice was administered or that new and necessary legislation was put into place.

Kilclooney dolmen, County Donegal.18

19

The Brehon’s Chair, Rathfarnham, County Dublin.20

Judgements were given at known gathering places such as ancient monuments or under a sacred tree.

21Over time, the codex of laws inevitably expanded as they reflected new circumstances and events. It became too extensive, too detailed, for any but the most learned minds to encompass and preserve for future generations. They thus became the province of the wisest, the acknowledged holders of knowledge and wisdom; that is, the elite, learned class formerly known as druids.

ASK THE WISE ONES

Much has been written, and much more imagined or fantasised, about the druid class of ancient Ireland, but quite simply they were the wise ones, the holders of the most important knowledge and wisdom, the only ones who could be relied upon to recite from memory a complex family history, or recount the details of an important strategic battle. They were well versed in medical knowledge and the lore of herbs; they could anticipate the movements of the sun, moon and stars, and forecast weather patterns. Besides this, they were the holders and preservers of the most ancient legends, songs and epic poems, which encapsulated priceless folk memories of the dim and distant past. In this they were similar to the wise ones of many other cultures, the original natives of places such as Russia and North America. 22

REMEMBER, REMEMBER …

Druids held in their prodigious memories the laws and decisions made and passed on over centuries. They were able to recall these to public hearings, where judgements were based on them. In druidic circles, memory was all. Ancient Ireland certainly knew of writing, and had indeed evolved its own unique form of coded communication known as Ogham, a system of straight lines cut at different angles into rods of yew, rowan or hazel, to send messages. Ogham was also used to cut inscriptions on to standing stones, and while the ogham rods have, alas, not survived, the stones have. They can still be seen all over Ireland.

Gurranes Stone Row, near Castletownshend, County Cork.23

Ogham stone at Kilmakedar, County Kerry.

24It was a central belief of druidic learning that their arcane knowledge should never be written down, but instead committed to memory. In this way, it could be guarded from those who might seek to use it wrongfully. Much the same belief is still followed in magical circles today, when a specific ingredient, word or action is deliberately left out of a recorded spell, only to be inserted at the final moment by one of the elect.

The Senchus of the men of Erin: What has preserved it? The joint memory of two seniors, the tradition from one ear to another, the composition of poets, the addition from the law of the letter, strength from the law of nature; for these are the three rocks by which the judgments of the world are supported. [Senchus Mór]

The amount of information to be committed to memory was thus enormous. Not just the case law of previous judgements, but also family histories, epic poems and legends, and general natural knowledge. This was achieved principally by putting the details into poems or rhyme, which made them easier to remember.

Ogham stones hold secrets of the past.

25THE GREAT LAW SCHOOLS OF ANCIENT IRELAND

There were many schools where students were trained in this demanding discipline, and such academies of learning were known throughout Europe. Kings and nobles sent their children to be educated here, for even if they had no intent or ability to become druids, the education and training they got would stand them in excellent stead in future years. At one time, there were students from no fewer than eighteen different countries studying at Durrow, and there was a school specialising in the teaching of medicine at Tuam Brecain (modern Tomregan, near Belturbet in County Cavan). Alfrith, son of Oswy, who ruled Northumbria in the seventh century, came to Ireland in his youth to learn, and there is also evidence that King Alfred of England, the man credited with collecting and establishing a system of laws in that country, received his first training in an Irish law school around the ninth century.

Some great families of brehon teachers continued for centuries, and were still running law schools right up to Tudor times, among them the Mac Aodhagáins or MacEgans of Tipperary and the O’Davorens of Clare.

King Alfred the Great of England.

The earliest surviving manuscripts of several law compilations (i.e. when laws were written down, rather than passed on from memory) are believed to have 26been compiled at MacEgan law schools. We can even hear the actual voice of one of the family through a touching note scribbled on the margin of a vellum leaf:

One thousand three hundred ten and forty years from the birth of Christ till this night; and this is the second year since the coming of the plague into Ireland. I have written this in the twentieth year of my age. I am Hugh, son of Conor MacEgan, and whoever reads it, let him offer a prayer of mercy for my soul. This is Christmas night, and on this night I place myself under the protection of the King of Heaven and Earth, beseeching that He will bring me and my friends safe through this plague, etc. Hugh (son of Conor, son of Gilla-na-naeve, son of Dunslavey) MacEgan, who wrote this in his own father’s book in the year of the great plague. [Senchus Mór]

The Black Death or bubonic plague was indeed ravaging Ireland in 1350, which gives stark reality to Hugh’s desperate cry. It seems he did survive on that occasion, though; a decade later, in 1359, the Annals of the Four Masters records the death of Hugh, son of Conor MacEgan, ‘the choicest of the Brehons of Ireland’. (Family names of Egan and Keegan, incidentally, are derivatives of the original Mac Aodhagáin or MacEgan.)

The O’Davorens (or Ó Duibhdábhoireanns) of Corcomroe in County Clare were renowned for their knowledge of both history and the law, and they passed this on in their schools. They also acted as brehons for the local O’Loughlin rulers. 27They held estates in the Burren down to the time of the Cromwellian conquests, and the ruins of their famed law school at Cahermacnaghten can still be seen today.

Redwood Castle, stronghold of the MacEgans, near Lorrha, County Tipperary.

Women, it should be noted, were also learned druids, and later brehons, studying alongside their male counterparts and achieving fame for their decisions:

As decided by Brigh Bruighaidh… the female author of the true mode of taking lawful possession, who dwelt at Fesen, i.e. the fort of Magh Deisitin in Uladh. [Senchus Mór] 28

Ruins of the O’Davoren law school, Cahermacnaghten, County Clare.

THE COMING OF CHRISTIANITY

We have seen that Ollamh Fodhla is credited with bringing together all the existing laws of Ireland sometime between 1000 and 700 BC. In the fifth century AD, the newly-arrived Christian missionaries decided to do the same thing, and in the process, rid those laws of some facets unacceptable to Christianity.

It doesn’t read like that in the Church’s own records of course: according to these, Ireland had existed in a pitiable state before the advent of wiser, more enlightened minds from Rome, and it was only with this timely help that we were enabled to look confidently to the future. Well, it has long been accepted that history is written by the winners, not the losers, and Christianity had a good long run with its ironclad ‘gospel truth’. 29

WRITING IT DOWN – WITH AMENDMENTS

We weren’t entirely the losers though. The existing brehon laws were certainly committed to writing by Christian scribes around the fifth century. St Patrick is credited with organising this major event, but that need not be taken as a given. To do even a tenth of the things the hagiography credits him with, Patrick would have had to work nonstop, day and night, for several lifetimes. It should also be noted that his biographer Benignus records Patrick as burning a very large number of ancient texts that had formerly been used by the brehons, since he regarded them as pagan and therefore unacceptable. If this is true, destroying priceless sources definitely puts a black mark against Patrick’s name.